Abstract

Because articular cartilage does not self-repair, tissue-engineering strategies should be considered to regenerate this tissue. Autologous chondrocyte implantation is already used for treatment of focal damage of articular cartilage. Unfortunately, this technique includes a step of cell amplification, which results in dedifferentiation of chondrocytes, with expression of type I collagen, a protein characteristic of fibrotic tissues. Therefore, the risk of producing a fibrocartilage exists. The aim of this study was to propose a new strategy for authorizing the recovery of the differentiated status of the chondrocytes after their amplification on plastic. Because the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2 and the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 are cytokines both proposed as stimulants for cartilage repair, we undertook a detailed comparative analysis of their biological effects on chondrocytes. As a cellular model, we used mouse chondrocytes after their expansion on plastic and we tested the capability of BMP-2 or TGF-β1 to drive their redifferentiation, with special attention given to the nature of the proteins synthesized by the cells. To prevent any fibrotic character of the newly synthesized extracellular matrix, we silenced type I collagen by transfecting small interfering RNA (siRNA) into the chondrocytes, before their exposure to BMP-2 or TGF-β1. Our results showed that addition of siRNA targeting the mRNA encoded by the Col1a1 gene (Col1a1 siRNA) and BMP-2 represents the most efficient combination to control the production of cartilage-characteristic collagen proteins. To go one step further toward scaffold-based cartilage engineering, Col1a1 siRNA-transfected chondrocytes were encapsulated in agarose hydrogel and cultured in vitro for 1 week. The analysis of the chondrocyte–agarose constructs by using real-time polymerase chain reaction, Western-blotting, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy techniques demonstrated that the BMP-2/Col1a1 siRNA combination is effective in reinitializing correct production and assembly of the cartilage-characteristic matrix in agarose hydrogel, without production of type I collagen. Because agarose is known to favor long-term expression of the chondrocyte phenotype and agarose-based hydrogels are approved for clinical trials, this strategy appears very promising to repair hyaline cartilage.

Introduction

The biomechanical properties of articular cartilage result from its content in specific extracellular matrix proteins synthesized by the only cell type present, the chondrocyte. The aggrecan macromolecules offer cartilage its load-bearing ability, whereas the collagen network provides the tissue with its tensile resistance. The healing capabilities of cartilage are very poor since this tissue is not vascularized. Common surgical treatments (microfracture, mosaicplasty) most often lead to the production of a tissue that contains type I collagen, a protein characteristic of fibrotic tissues, rather than type II collagen, the most abundant protein found in hyaline cartilage. This resulting fibrocartilage does not offer the biomechanical properties necessary for correct function of joints. In this context, cell therapy and tissue-engineering techniques are requested to repair cartilage. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) was the first cell therapy procedure used in orthopedics to treat the focal damage of articular cartilage. In this method, chondrocytes are collected from a healthy site and amplified in vitro before grafting. Unfortunately, during this amplification step, chondrocytes dedifferentiate as illustrated by a switch from type II to type I collagen expression.1 Therefore, the risk of producing a fibrocartilage persists with this method. Today, the international health agencies that survey ACI advise to improve the method by using (1) soluble factors to maintain or restore the differentiated phenotype of chondrocytes and (2) a three-dimensional (3D) scaffold to extend the method to developing osteoarthritic lesions.2

Regarding soluble factors, the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2 and the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 both proposed as therapeutic molecules for cartilage repair. As a first attempt to compare the capabilities of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 to direct redifferentiation of chondrocytes, we used embryonic mouse chondrocytes, a cell model routinely used in our laboratory.3–8 We found that BMP-2 was more effective than TGF-β1 to restore the chondrogenic character of chondrocytes, as judged by the re-expression of specific chondrocytic markers such as Sox9, α10 integrin subunit, and type IIB procollagen isoform.5 However, this redifferentiation occurred to a certain extent only, since type I collagen expression persisted indifferently after the addition of BMP-2 or TGF-β1.5 Recently, we also demonstrated that BMP-2 could enhance the expression of chondrogenic markers in human articular or nasal chondrocytes during their in vitro amplification without any expression of hypertrophic or osteogenic markers.9,10 More precisely, we found that BMP-2 favors the ratio of type II/type I collagen mRNA levels.9,10 This feature is important since this ratio is considered as a differentiation index for chondrocytes11 and is now required for quality control of chondrocytes before grafting. Besides, although TGF-β1 administration has been shown to stimulate proteoglycan and type II collagen production in goat articular chondrocytes amplified in monolayer cultures,12 a more recent study has revealed that TGF-β1 exposure during expansion of human articular chondrocytes induces a switch to hypertrophy,13 compromising therefore the application of TGF-β1 for cartilage cell therapy.

In view of the above results and with the aim of better evaluating the potential of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 as clinical tools for cartilage repair, we undertook in the present study a detailed comparative analysis of the biological effects of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 on nonembryonic mouse chondrocytes, after monolayer expansion. We focused our analyses on the nature of extracellular matrix proteins synthesized by the cells, particularly those of the collagen family. In addition, to prevent any fibrotic character of the neo-synthesized matrix, we silenced type I collagen by transfecting small interfering RNA (siRNA) into the chondrocytes, before their exposure to BMP-2 or TGF-β1. Our results showed that addition of siRNA targeting the mRNA encoded by the Col1a1 gene (Col1a1 siRNA) and BMP-2 represents the most efficient combination to control the production of cartilage-characteristic collagen proteins. To go one step further toward scaffold-based cartilage engineering, we then investigated the stability of the chondrocytic phenotype when Col1a1 siRNA-transfected chondrocytes were cultured in agarose hydrogel with BMP-2. Agarose or agarose/alginate hydrogels are attractive scaffolds for cartilage repair because they homogenously suspend cells within a 3D environment and are easy to shape and calibrate. We evaluated the phenotypic outcomes of the chondrocyte–agarose constructs by Western blotting, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy analyses.

Materials and Methods

Monolayer cell culture

Cell amplification

Mouse chondrocytes were isolated from the rib cages of new-born mice from the same liter (10 to 12 animals), the method was adapted from Lefebvre et al.14 These chondrocytes were seeded on 75-cm2 Corning flasks with 1×106 cells/flask (P0) and cultured with a 1:1 Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F-12 (with GlutaMAX-I) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin (Invitrogen), at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Monolayer cell culture treatment

After 1 week of amplification, cells were confluent, and then trypsinized (0.05% trypsin-EDTA) and seeded in six-well culture dishes at the density of 1.5×105 cells/well and cells at this stage were designated P1. For treatment with growth factors, after 24 h of adhesion, cells were grown for 3 days in a medium containing 1% insulin transferrin selenium (ITS; Gibco) and 20 μg/mL ascorbic acid sodium salt (Sigma) supplemented or not with 50 ng/mL BMP-2 (R&D Systems) or 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 (R&D Systems). The culture medium was daily changed.

3D cell culture: preparation and culture of chondrocyte–agarose constructs

The chondrocyte–agarose constructs were prepared as previously described by Bougault et al.3,4 Briefly, after cell amplification, trypsinization, and transfection, P1 chondrocytes were embedded in 2% agarose (Seaplaque, Cambrex BioScience) with a density of 2×106 cells/mL. Constructs were then placed in six-well culture dishes and treated for 7 days with a medium containing 1% ITS and 20 μg/mL ascorbic acid supplemented or not with 50 ng/mL BMP-2. The culture medium was daily changed.

Microporation transfection of siRNA

We transfected chondrocytes with siRNA targeting specifically the mRNA encoded by the Col1a1 gene (designated as Col1a1 siRNA). The target sequence was 5′-GGAAUUCGGACUAGACAUU-3′ and was purchased from Thermo Scientific. Transient transfection of chondrocytes was performed using microporation (Microporator MP100, Digital Bio, Labtech France). Briefly, P1 cells were suspended in a resuspension buffer at the density of 1×106 cells/mL and incubated with 25 pmol siRNA (250 nM) according to the manufacturer's instructions (NEON Transfection System Kit, InVitrogen). A siRNA directed against the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and provided with the siRNA test kit (Amaxa) was used as control. Then, microporation was performed at room temperature using the following program: 1400 voltage, 20 ms, and 2 pulses. After electroporation, cells were seeded in 24-well culture dishes for monolayer culture or were embedded in agarose for 3D culture.

Gene expression analysis using reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

Total RNAs of cells cultured in monolayer were extracted using the NucleoSpin RNA II kit (Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protocol of RNA extraction from chondrocyte–agarose constructs was adapted from the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) procedure as previously described.3 The reverse-transcription of total RNAs was then performed as previously described.7

Type II collagen isoforms transcripts were amplified by conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a PCR thermal cycler MyCycler (Bio-Rad) using primers as previously described5 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Polymerase Chain Reaction Primer Sequences

| Genes | Primers sequence (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rpl13a | Forward: atccctccaccctatgacaa Reverse: gccccaggtaagcaaactt |

97 | NM_009438.5 |

| Col2a1 | Forward: caggtgaacctggacgagag Reverse: accacgatctcccttgactc |

86 | (Salvat et al., 2005)42 |

| Col1a1 | Forward: aacgagatcgagctcagagg Reverse: gactgtcttgccccaagttc |

99 | (Salvat et al., 2005)42 |

| Col9a1 | Forward: ccccaggagaggttggac Reverse: tcctaccgggcctctactg |

62 | NM_007740.3 |

| Col10a1 | Forward: caaacggcctctactcctctga Reverse: cgatggaattgggtggaaag |

127 | (Cormier et al., 2003)43 |

| Agc1 | Forward: gtgcggtaccagtgcactga Reverse: gggtctgtgcaggtgattcg |

103 | NM_007424.2 |

| Sox9 | Forward: gaggccacggaacagactca Reverse: cagcgccttgaagatagcatt |

50 | (Huang et al., 2004)44 |

| Col2a1conventional PCR | Forward: gcctcgcggtgagccatgatgatc Reverse: ctccatctctgccacggggt |

IIA: 472IIB: 268 | (Valcourt et al., 1999)45 |

PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Real-time PCR amplifications were performed as previously described9 in a PCR thermal cycler ICycler (Bio-Rad) using the SYBR Green technology (Table1) and the comparative Ct method was used for the analyses.15 Housekeeping gene was ribosomal protein L13a (RPL13a).

Protein extraction and analysis

Protein extraction from cells cultured in monolayer and cell-agarose constructs were performed as described by Gouttenoire et al.5 and Bougault et al.,4 respectively. Briefly, cells in monolayer were scraped into 100 μL Laemmli sample buffer. Chondrocyte-agarose constructs were frozen in liquid nitrogen, freeze-dried and resuspended in 200 μL Laemmli sample buffer. Collagens present in the culture medium were precipitated using 4.5 M NaCl and resuspended in 50 μL Laemmli sample buffer. For protein quantification, equivalent volumes of samples were separated on 11% polyacrylamide gel and stained by coomassie-blue, in a first run. If necessary, volumes were then adjusted. Proteins were then separated on polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, probed (antibodies used are referenced in Table 2) and revealed as previously described.5

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Antibodies

| Target protein | Antibodies | Dilution | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Type II collagen | Monoclonal anti-type II collagen (Clone 2B1) | IF: 1:100 IH: 1:100 | Thermo Fischer Scientific (No.: MA137493)46 |

| Type II collagen | Polyclonal anti-type II collagen | IB: 1:2000 | Novotec (ref. 20251) | |

| Type IIA collagen | Polyclonal anti-type IIA collagen | IF: 1:1000 IB: 1:2000 | (Oganesian et al., 1997)47 | |

| Type I collagen | Polyclonal anti-type I collagen | IF: 1:100 IH: 1:100 IB: 1:2000 | Novotec (ref. 20151) | |

| Aggrecan | Polyclonal anti-aggrecan | IF: 1:100 | Novotec (ref. 24421) | |

| Type IX collagen | Monoclonal anti-type IX collagen (Clone 23-5D1) | IB: 1:3000 | (Warman et al., 1993)48 | |

| Sox9 | Polyclonal anti-Sox9 | IB: 1:1000 | Chemicon (ref. AB5535) | |

| Actin | Polyclonal anti-Actin | IB: 1:800 | Sigma-Aldrich (ref. A5060) | |

| Secondary Antibodies | HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit | 1:2000 | Cell Signaling (#7074) | |

| Cy2-conjugated anti-rabbit | 1:100 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | ||

| Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit | 1:200 | Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories | ||

| IgG-AP-conjugated anti-rabbit | 1:5000 | Bio-Rad (ref. 170-6518) | ||

| IgG-AP conjugated anti-mouse | 1:5000 | Bio-Rad (ref. 170-6520) |

IF, immunofluorescence; IH, immunohistochemistry; IB, immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence

P1 chondrocytes were seeded on glass coverslips in six-well culture dishes and were cultured under the different conditions described above, for 3 days. The cell cultures were then processed as described by Valcourt et al.7 The collagens were visualized by using the appropriated antibodies (Table 2). The nuclei were visualized by staining with 0.25 μg/mL Hoechst (Fluka). Observation by epifluorescence of the coverslips was realized with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with a CoolSNAP Fx camera (Roper Scientific). Images were analyzed with ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Histological examinations of the chondrocyte-agarose constructs were performed after 7 days of in vitro culture. The constructs were assessed histologically and immunohistochemically as previously described.3,16

Electron microscopy analysis

The cell-agarose constructs were cut in small pieces and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde-2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at room temperature. The samples were subsequently assessed for electron microscopy analysis as previously described.17 After uranyl acetate in methanol and lead citrate treatment, samples were observed using a electron microscope (Philips CM120) equipped with a digital camera (Gatan Orius 200 2Kx2K; “Centre Technologique des Microstructures,” Université Lyon I)

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-Test for nonparametric analysis was used for comparison and statistical significance was accepted at p<0.05.

Results

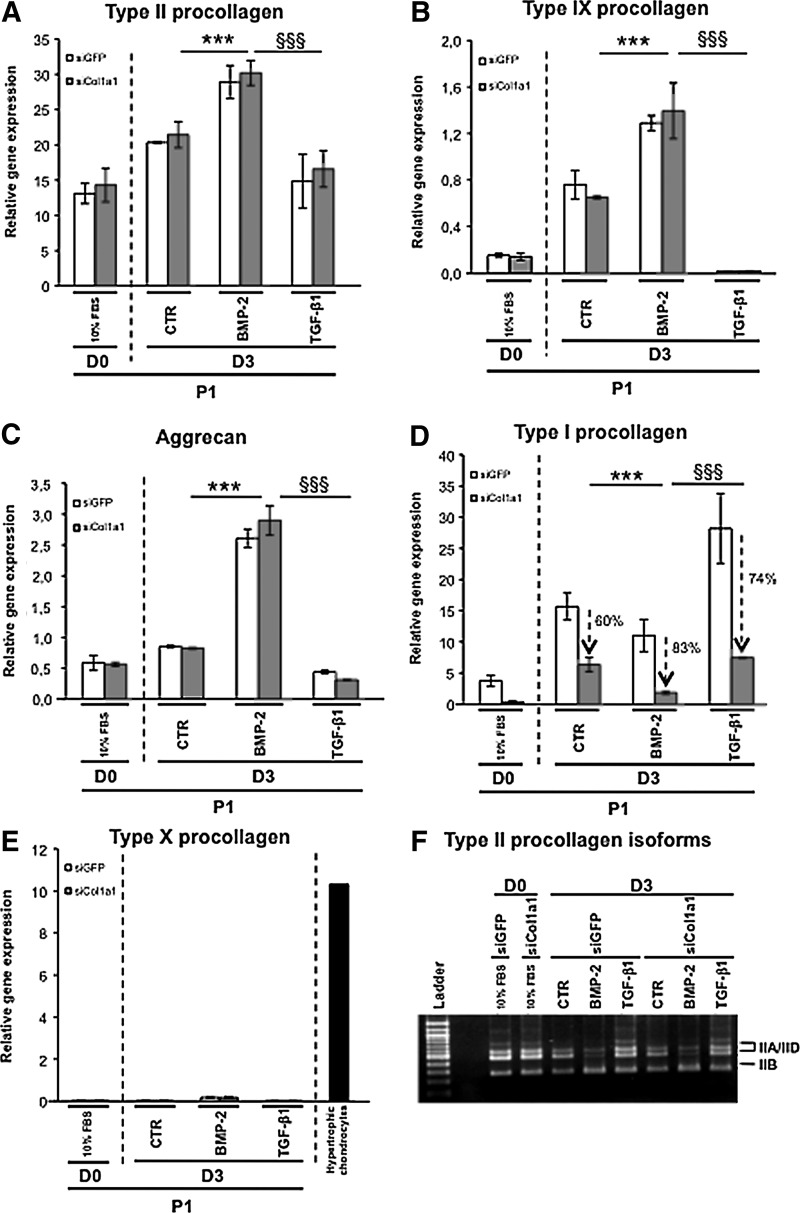

Differential effects of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 on collagen synthesis

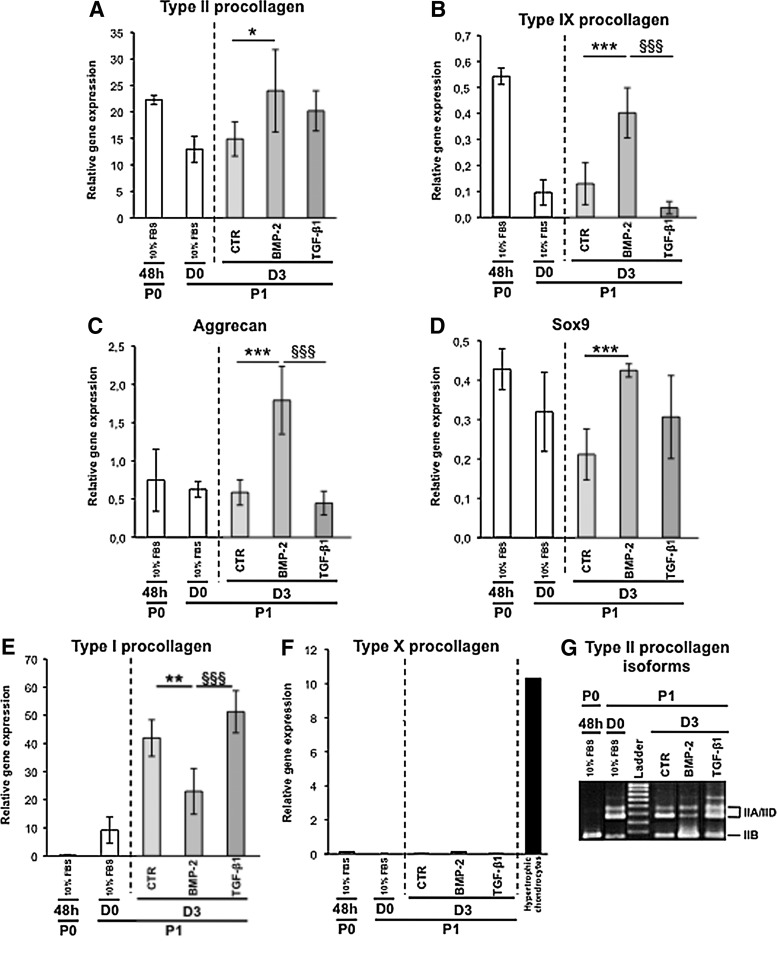

After 1 week of amplification in monolayer culture, chondrocyte dedifferentiation occurred as expected and attested by the general decrease in expression observed for the genes coding for type II procollagen (Col2a1), type IX procollagen (Col9a1), aggrecan (aggrecan), and the transcription factor Sox9 (Sox9), all markers of the well-differentiated phenotype of chondrocytes (Fig. 1A–D). In parallel, a switch in the expression of the cartilage-characteristic IIB isoform toward the more mesenchymal IIA/IID isoforms of type II procollagen was noted (Fig. 1G). The loss of these chondrogenic signatures was furthermore accompanied by the gain of expression of Col1a1, a gene coding for type I procollagen, and this feature is a classical trait of chondrocyte dedifferentiation (Fig. 1E).

FIG. 1.

(A–F) Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of mRNA levels of the indicated phenotypic markers in chondrocytes cultured as P0 for 48 h in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (48 h) or cultured as P1 for 24 h in the presence of 10% FBS (D0), and then for 3 days (D3) in the presence of 1% insulin transferrin selenium (ITS) alone control (CTR) or supplemented with the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP-2) or transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, as indicated. (F) Hypertrophic chondrocytes: type X procollagen mRNA levels in hypertrophic chondrocytes isolated from the ventral parts of rib cages isolated of newborn mice. The data represent the mean±SD (n=5; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, significant effects of BMP-2 versus CTR; §§§ p<0.001, significant effects of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 versus BMP-2). (G) Conventional PCR amplification of the type II collagen isoform transcripts (IIA/D: nonchondrogenic form and IIB: chondrogenic form) in chondrocytes cultured as described ahead. These results are representative of three separate cultures.

We next undertook a comparative analysis of the biological effects of BMP-2 or TGF-β1 on these dedifferentiated chondrocytes. After 3 days in culture, expression of the chondrogenic markers in P1 chondrocytes was the highest in the presence of BMP-2 (Fig. 1A–D). This chondrogenic reconversion triggered by BMP-2 was also illustrated by the re-expression of the chondrogenic IIB isoform of type II procollagen, whereas TGF-β1 clearly favored expression of the IIA/IID isoforms and Col1a1 (Fig. 1G). Interestingly, the lowest level of Col1a1 expression measured on day 3 was observed for the chondrocytes cultured in the presence of BMP-2 (Fig. 1E). Last, because BMP-2 contributes to the terminal differentiation of chondrocytes, we surveyed expression of Col10a1 coding for type X collagen characteristic of hypertrophy,18 but no induction of this gene was recorded in our cultures (Fig. 1F).

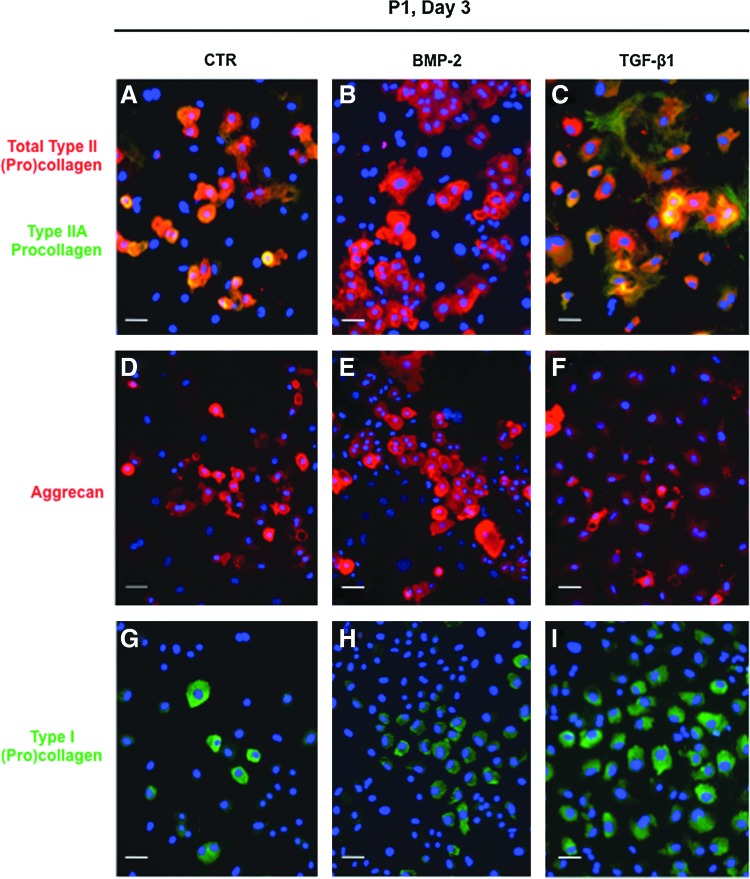

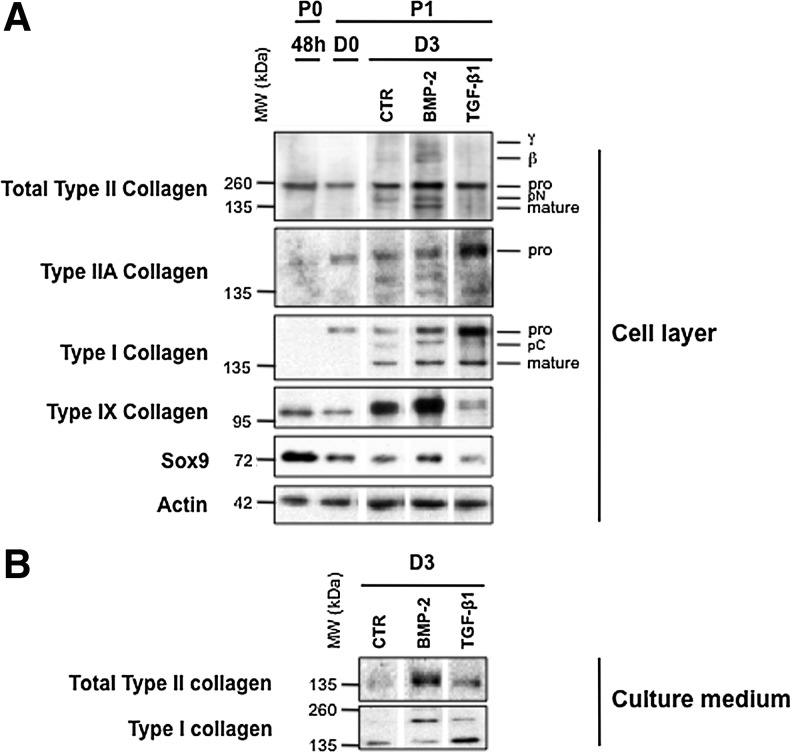

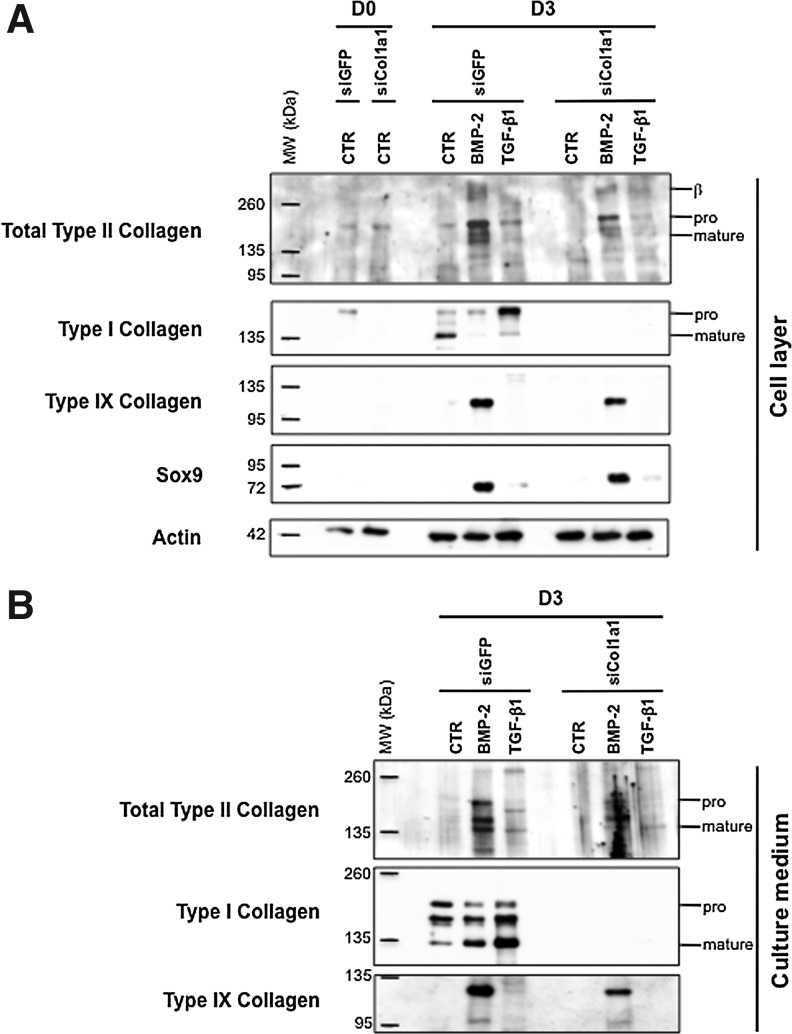

In parallel cultures, we compared the effects of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 on P1 chondrocytes at the protein level. Immunofluorescence analysis clearly showed that BMP-2 was most efficient to stimulate type II procollagen and aggrecan synthesis, as revealed by the highest proportion of cells stained with an anti-type II collagen antibody (2B1) or with an anti-aggrecan antibody (Fig. 2B, E). More accurately, double immunostaining with 2B1 and anti-type IIA collagen antibody indicated that most TGF-β1-treated cells positive with 2B1 synthesized in fact the IIA form of type II procollagen, whereas the presence of this isoform was barely detectable in BMP-2-treated chondrocytes (Fig. 2B, C). It should be added that most TGF-β1-treated cells are stained with an anti-type I procollagen antibody, whereas less cells stained for this collagen in the presence of ITS or BMP-2 (Fig. 2G–I). Thus, this first examination of the effects of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 on protein synthesis was consistent with the profiles of corresponding mRNA expressions obtained by real-time PCR. Moreover, immunoblotting analyses confirmed that after 3 days in culture, BMP-2 was the most efficient to enhance total type II procollagen synthesis. In complement, BMP-2 was also able to stimulate synthesis of type IX collagen, another important component of the collagen fibrils in hyaline cartilage19 and Sox9, a transcription factor required for cartilage formation20 (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, TGF-β1 inhibited synthesis of total type II procollagen (while favoring the nonchondrogenic IIA form), type IX collagen, and Sox9, but stimulated type I collagen production (Fig. 3A). The same differential effects of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 on type II and type I collagen production was also observed in the culture medium (Fig. 3B) attesting that these effects concern truly total collagen synthesis.

FIG. 2.

Immunofluorescence staining of P1 chondrocytes cultured for 3 days in the presence of 1% ITS alone (A, D, G) or supplemented with bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2 (B, E, H) or TGF-β1 (C, F, I). From A to C, cells were double stained for type II collagen with the Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (red) and for type IIA procollagen with the Cy2-conjugated secondary antibody (green). From D to F, cells were stained for aggrecan with the Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (red). From G to I, cells were stained for type I collagen with the Cy2-conjugated secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye (blue). Scale bar=50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 3.

(A) Western blotting analysis of type II, IIA, I, IX collagens, and Sox9 in the cell layer when chondrocytes were cultured as P0 for 48 h in the presence of 10% FBS (48 h) and cultured as P1 for 24 h in the presence of 10% FBS, (D0) then for 3 days in the presence of 1% ITS alone or supplemented with BMP-2 or TGF-β1 (D3). At the bottom of the panel, immunoblotting for actin is shown as a loading control. On the right, the positions of mature collagen chains (mature) and unprocessed (pro) or processing intermediate of procollagen containing amino-propeptide (pN) or carboxy-propeptide (pC) are indicated. The upper bands represent dimers (β) or trimers (γ) of type II collagen molecules. (B) Western blotting analysis of type II and I collagens synthesized and secreted in the culture medium (of the cell layer analyzed in A) when chondrocytes were cultured as P1 for 3 days in the presence of 1% ITS alone or supplemented with BMP-2 or TGF-β1 (D3). These results are representative of five separate cultures.

Taken together, this first series of analyses demonstrated that BMP-2 offers a better potential than TGF-β1 to induce recovery of the differentiation state of chondrocytes, as judged by the expression of genes and corresponding proteins characteristic of cartilage. Nevertheless, this recovery was limited to a certain extent since a low level of type I collagen synthesis was still observed in the presence of BMP-2 (Figs. 2 and 3).

The combination of BMP-2 and siRNA targeting Col1a1 promotes selective synthesis of cartilage-characteristic proteins

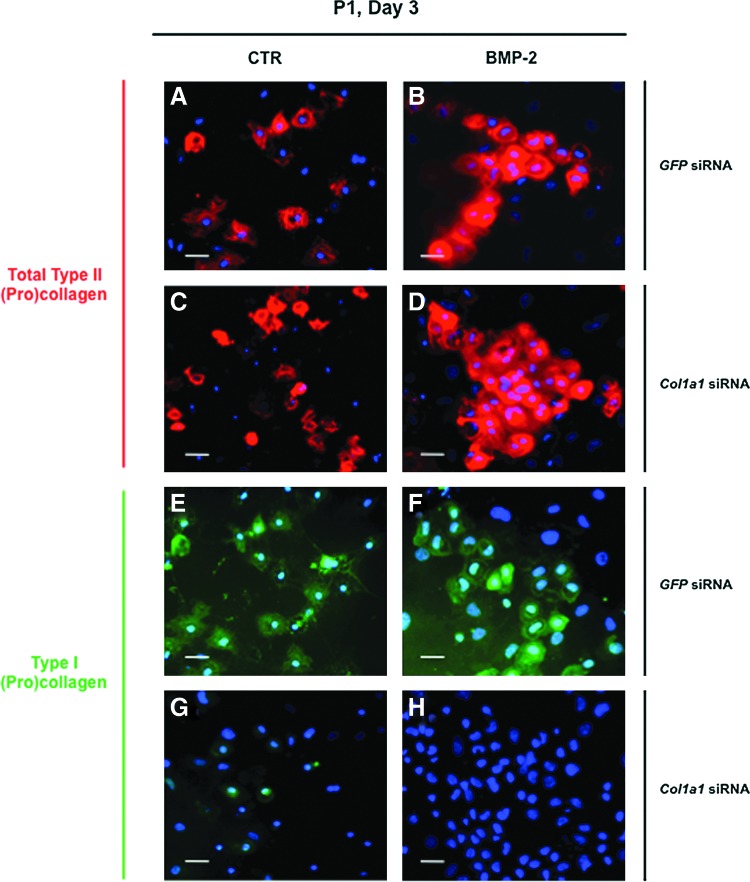

In an attempt to overcome the expression of type I collagen, we transfected chondrocytes with siRNA targeting specifically the mRNA encoded by the Col1a1 gene (designated as Col1a1 siRNA). We transfected P1 chondrocytes just before their plating and we first analyzed by immunofluorescence the effect of Col1a1 knockdown on collagen synthesis in cells cultured in the presence of ITS alone or supplemented with BMP-2. As a control, P1 chondrocytes were transfected with a siRNA oligonucleotide targeting GFP (designated as GFP siRNA). When cells were examined 3 days after their transfection with GFP siRNA or Col1a1 siRNA, the stimulatory effect of BMP-2 on total type II procollagen synthesis was evidenced by the higher proportion of cells that were positively stained with the 2B1 antibody, when compared to transfected cells cultured in the presence of ITS alone (Fig. 4A–D). There was also indication of efficient Col1a1 knockdown in cells transfected with Col1a1 siRNA, as illustrated by the rare cells stained for type I procollagen in comparison with cells transfected with GFP siRNA (Fig. 4E–H). To evaluate more quantitatively the efficiency and specificity of Col1a1 siRNA, we analyzed by PCR and Western blotting the phenotype of P1 chondrocytes that were transfected with Col1a1 siRNA or GFP siRNA, and then treated with BMP-2 or TGF-β1. When the profiles of mRNA levels were examined, there was clear evidence of Col1a1 knockdown by Col1a1 siRNA. For instance, over 80% suppression relative to GFP siRNA control was measured for the cells treated with BMP-2 (Fig. 5D). Noticeably, when the cells were treated with TGF-β1, which induces high levels of Col1a1 expression, this expression was still suppressed over 70% by Col1a1 siRNA (Fig. 5D). At the same time, Col1a1 siRNA had no effect on the other genes (Fig. 5). Transfection with Col1a1 siRNA also led to marked suppression of the type I procollagen protein without affecting other chondrogenic proteins, as unambiguously demonstrated by Western blotting analysis of the cell layers and culture media (Fig. 6).

FIG. 4.

Immunofluorescence staining of P1 chondrocytes cultured for 3 days in the presence of 1% ITS alone (A, C, E, G) or supplemented with BMP-2 (B, D, F, H) after transfection with green fluorescent protein (GFP), small interfering RNA (siRNA) (A, B, E, F), or Col1a1 siRNA (C, D, G, H). From A to D, cells were stained for type II collagen with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (red). From E to H, cells were stained for type I collagen with Cy2-conjugated secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye (blue). Scale bar=50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

FIG. 5.

(A–E) Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA levels of the indicated phenotypic markers in P1 chondrocytes transfected with GFP siRNA or Col1a1 siRNA and cultured for 24 h in the presence of 10% FBS (D0) or for 3 days in the presence of 1% ITS alone (CTR) or supplemented with BMP-2 or TGF-β1 (D3). (E) Hypertrophic chondrocytes: type X procollagen mRNA levels in hypertrophic chondrocytes isolated from the ventral parts of rib cages isolated of newborn mice. The data represent the mean±SD (n=3; ***p<0.001, significant effects of BMP-2 versus CTR in chondrocytes transfected with Col1a1 siRNA; §§§ p<0.001, significant effects of TGF-β1 versus BMP-2 in chondrocytes transfected with Col1a1 siRNA). (F) Conventional PCR amplification of the type II collagen isoforms transcripts (IIA/D: nonchondrogenic form and IIB: chondrogenic form) in chondrocytes cultured as described ahead. These results are representative of three separate cultures.

FIG. 6.

(A) Western blotting analysis of type I, II, IX collagens, and Sox9 in the cell layer when P1 chondrocytes were transfected with GFP siRNA or Col1a1 siRNA and cultured for 24 h in the presence of 10% FBS (D0), and then for 3 days in the presence of 1% ITS alone or supplemented with BMP-2 or TGF-β1 (D3). At the bottom of the panel, immunoblotting for actin is shown as a loading control. (B) Western blotting analysis of type I and II collagens in the culture medium (of the cell layer analyzed in A) when chondrocytes were cultured as P1 for 3 days in the presence of 1% ITS alone or supplemented with BMP-2 or TGF-β1 (D3). On the right, the positions of mature collagen chains (mature) and unprocessed (pro) procollagen are indicated. Dimers of type II collagen molecules are also indicated (β). These results are representative of three separate cultures.

Taken together, these data demonstrate effective and specific suppression of type I procollagen production by Col1a1 siRNA. They also demonstrate that BMP-2 and Col1a1 siRNA is an effective combination to selectively re-induce production of cartilage proteins by chondrocytes, after their amplification and dedifferentiation in culture.

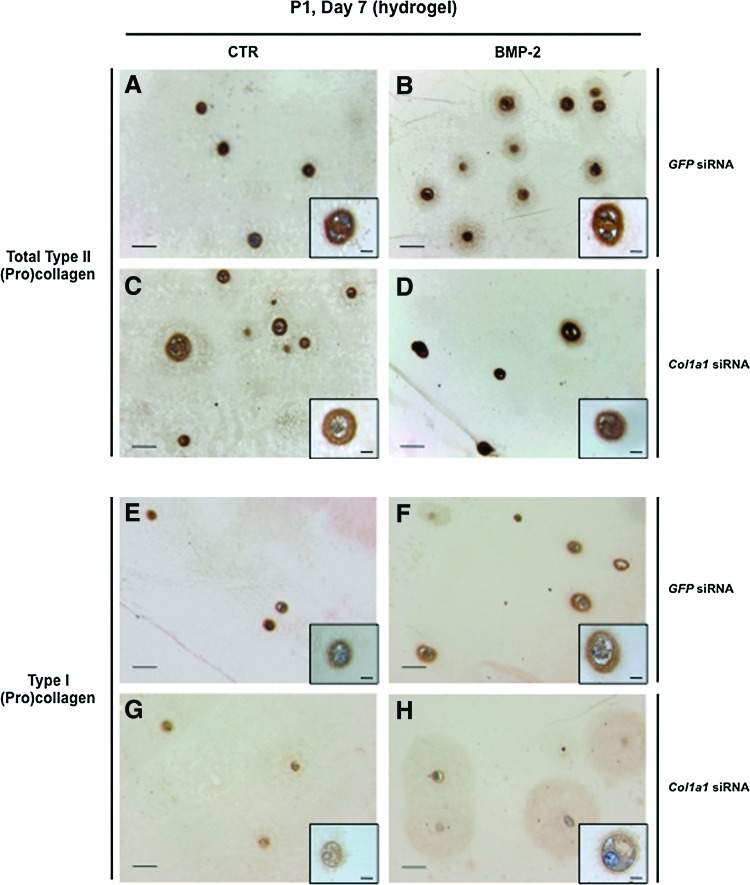

The BMP-2/Col1a1 siRNA combination promotes production and assembly of cartilage-characteristic matrix in hydrogel

Next, we evaluated the potential of the BMP-2/Col1a1 siRNA combination to promote hydrogel-based engineered cartilage formation. In this context, P0 chondrocytes were amplified in monolayer culture, and then were trypsinized and transfected with Col1a1 siRNA or GFP siRNA before their embedding in agarose gels. These chondrocyte–agarose constructs were cultured for 7 days in the presence of ITS supplemented or not with BMP-2, to allow extracellular matrix deposition. In all these conditions, P1 chondrocytes maintained their round morphology and type II collagen accumulated at the cell periphery, as shown by strong immunostaining (Fig. 7A–D). More precisely, type II collagen deposition spread further than the proximate cell periphery (Fig. 7B, D) and this topography (chondrocytes plus their environment), very interestingly recalls the chondron units described in articular cartilage.21 Type I collagen was also immunodetected in the cells and at their periphery when they were previously transfected with GFP siRNA (Fig. 7E, F). Noticeably, the intensity of type I collagen immunostaining appeared much weaker when the cells were previously transfected with Col1a1 siRNA (Fig. 7G, H).

FIG. 7.

Immunohistochemical staining for type II (A–D) and type I (E–H) collagen in chondrocyte–agarose constructs. P1 chondrocytes were transfected with GFP siRNA (A, B, E, F) or Col1a1 siRNA (C, D, G, H), and then embedded in agarose hydrogel and cultured for 7 days (D7) in the presence of 1% ITS alone (CTR; A, C, E, G) or supplemented with BMP-2 (B, D, F, H). Scale bars=100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tec

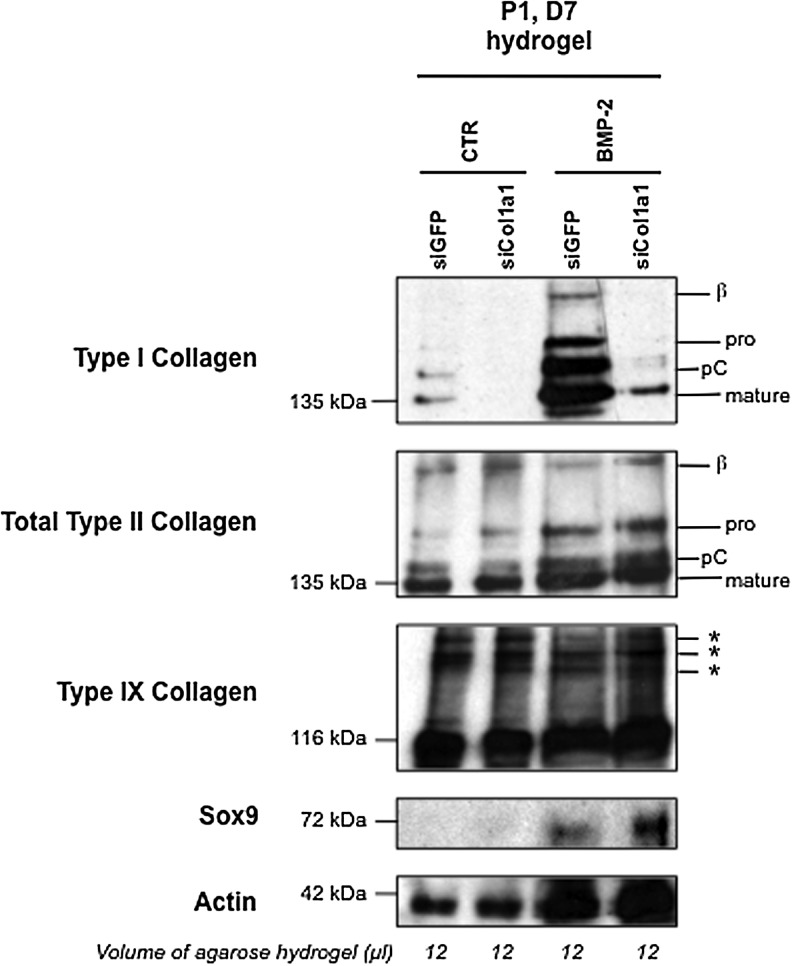

To gain a more quantitative appreciation of the protein content that was synthesized and deposited in gels after the 7-day culture period, chondrocyte–agarose constructs were analyzed by Western blotting. For all the samples examined, we compared the amount of proteins produced in equivalent volumes of gel. Higher levels of actin synthesis were observed in the constructs cultured in the presence of BMP-2 (Fig. 8), a sign of cell proliferation, and this was in good concordance with signs of cell division observed in the BMP-2-treated constructs (data not shown). It can be added that the stimulatory effect of BMP-2 on chondrocyte proliferation is routinely observed in cell culture experiments performed in our laboratory. Besides, our Western blotting analysis showed higher accumulation of proteins in the BMP-2-treated constructs, as evidenced by stronger staining intensities for type I, type II, type IX collagen, and Sox9 in comparison with the constructs treated with ITS alone (Fig. 8). Very importantly, type I collagen production was specifically and considerably knocked down by Col1a1 siRNA (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Western blotting analysis of type I, II, and IX collagens in chondrocyte–agarose constructs. P1 chondrocytes were transfected with GFP siRNA or Col1a1 siRNA, and then embedded in agarose hydrogel and cultured for 7 days (D7) in the presence of 1% ITS alone (CTR) or supplemented with BMP-2, as indicated. We compared the amount of proteins produced in equivalent volumes of agarose hydrogel (12 mL). On the right, the positions of mature collagen chains (mature) and unprocessed (pro) or processing intermediate of procollagen containing pC are indicated. The upper bands represent dimers (β) of type I and type II collagen molecules. Asterisks (*) represent covalent interchain crosslinks of type IX collagen molecules. These results are representative of three separate cultures.

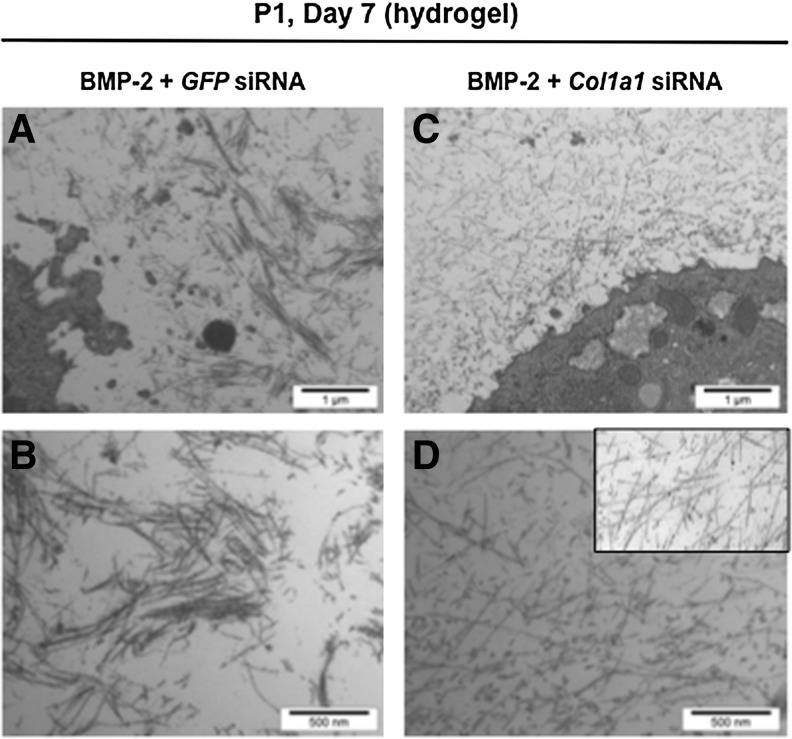

Interestingly enough, chondrocytes synthesized predominantly the mature form of type II collagen in agarose scaffolds, with interchain covalent crosslinks (Fig. 8). Thus, all the enzymatic machinery to ensure the cleavage of type II collagen precursor forms and the formation of the triple helical structure that can pack into fibrils22 was efficient in the hydrogels. Moreover, Western blot analysis of type IX collagen, another component of the cartilage collagen fibrils, also confirmed the presence of covalent crosslinks between collagen molecules (Fig. 8). All these observations suggested the presence of a fibrillar network and we next used transmission electron microscopy to examine the ultrastructure of the chondrocyte–agarose constructs, after transfection and culture for 7 days in the presence of BMP-2. After transfection with GFP siRNA, our observations revealed the presence of thin, but also thick collagen fibers that fuse (Fig. 9A, C) and show periodic striations at high magnification (data not shown). These traits are characteristic of type I collagen containing fibers, like found in fibroblastic tissues. However, after transfection with Col1a1 siRNA, only thin diameter collagen fibrils were observed (Fig. 9B, D), closely resembling collagen fibrils seen in native cartilage (Fig. 9D, inset).

FIG. 9.

Electron microscopy observations of the extracellular matrix synthesized by the chondrocytes in agarose hydrogel. P1 chondrocytes were transfected with GFP siRNA (A, B) or Col1a1 siRNA (C, D), embedded in agarose hydrogel and cultured for 7 days in the presence of BMP-2. Insert: electron micrograph of mouse rib cartilage. A, C: scale bars=1 μm; B, D: scale bars=500 nm.

Discussion

The present study was undertaken to examine first the potential of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 to stimulate re-expression of chondrogenic markers in mouse chondrocytes, after their dedifferentiation. Special attention was given to the nature of the extracellular matrix proteins synthesized by the cells, with a view of cartilage matrix reconstruction. Our results collectively and clearly show that BMP-2 has a better capability than TGF-β1 to stimulate chondrocyte redifferentiation, as revealed by our immunofluorescence and Western blotting analyses and this was also confirmed at the gene level, as shown by our PCR analyses. Interestingly, not only BMP-2 was found superior to TGF-β1 in stimulating type II collagen expression, but BMP-2 stimulates the cartilage-specific isoform (IIB) of type II procollagen, whereas TGF-β1 favors the expression of its nonchondrogenic form (IIA). What is more, TGF-β1 stimulates expression of type I collagen, whereas BMP-2 does not particularly enhance its expression. We previously reported similar differential effects of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 on type II collagen expression in embryonic mouse chondrocytes.5,7 The present work extends these observations on nonembryonic mouse chondrocytes with a detailed identification of other key proteins typical of well-differentiated chondrocytes, such as type IX collagen, aggrecan, and Sox9. Regarding more specifically the effect of BMP-2, the results presented here are also in the same vein of our previous studies where we showed that BMP-2 can stimulate chondrogenic expression in human nasal or articular chondrocytes expanded on plastic, without affecting type I collagen expression.9,10 Interestingly, Stewart et al.23 also showed that another type I procollagen gene (Col1a2) is not affected in equine articular chondrocytes cultured in the presence of BMP-2. Therefore, all these studies show that BMP-2 can act as a beneficial agent for the recovery of the chondrocyte phenotype, but at the same time, cannot hamper parallel type I collagen produced by dedifferentiated chondrocytes.

The second part of our study aimed to overcome the obstacle of type I collagen production. We chose to use antisense technology since other works have demonstrated its efficiency for inhibiting type I collagen expression in cells from different species, including human. For instance, human mesenchymal stem cells or skin fibroblasts transfected with COL1A1 siRNA showed effective downregulation of COL1A1.24,25 Yao et al.26,27 used recombinant adenoviral or lentiviral vector expressing both TGF-β3 and a short hairpin RNA targeting Col1a1 to control chondrogenesis in porcine mesenchymal stem cells and chondrocytes. This strategy resulted in effective suppression of type I collagen. All these results are in favor of using RNA interference for optimizing cell therapy and cartilage-engineering protocols. However, it should be noted that risks of genetic material recombination, integration into the host genome, or immune response exist with viral vectors and these traits are not suitable for clinical application. On the other hand, action of siRNA through transient transfection allows safe production of therapeutic cells. In this context, our objective here was to develop an ex vivo cell therapy rather than a gene therapy strategy to reinitialize chondrogenic capacities of dedifferentiated chondrocytes, by using a combination of BMP-2 and siRNA targeting Col1a1. It should be specified that type I collagen exists as a heterotrimer comprising two proα1(I) chains and one proα2 (I) chain. The proα1(I) chains have the ability to form homotrimers, as found in embryonic tissues and a variety of pathological situations,28–31 but proα2 (I) homotrimers have never been described and the inclusion of this chain into a trimer is considered dependent upon its association with proα1(I) chains. Therefore, blocking Col1a1 expression is necessary and sufficient to inhibit production of type I collagen. Our detailed analysis of the impact of Col1a1 siRNA transfection in chondrocytes cultured in monolayer confirmed indeed marked and specific suppression of type I procollagen (Figs. 4, 5 and 6). In preliminary experiments, we verified that our transfection conditions did not affect morphology, growth, or viability of chondrocytes (data not shown). Moreover, the differential effects of BMP-2 and TGF-β1 maintained on chondrocytes after their transfection further confirmed that the transfection procedure did not modify the responsiveness of chondrocytes to the growth factors. Taken together, our extensive molecular analysis of the chondrocytes cultured in monolayer demonstrated that BMP-2 and Col1a1 siRNA was the most effective combination to selectively reinitiate production of cartilage proteins by dedifferentiated chondrocytes. We also demonstrated that this combination was efficient to promote selective production of cartilage-characteristic matrix proteins, when applied to dedifferentiated chondrocytes cultured in agarose hydrogel. This is an important step toward hydrogel-based cartilage engineering. We show here that the chondrocyte phenotype was stabilized in agarose, 7 days after transfection. This represents a relatively short-term study, but our objective here was to demonstrate that the BMP-2/Col1a1 siRNA combination could be effective in reinitializing a program of chondrogenic differentiation, by using a scaffold suitable for cartilage engineering. It will be important to examine the phenotypic outcomes of chondrocyte-agarose constructs cultured over longer time but it is already encouraging to observe that BMP-2/Col1a1 siRNA combination favors accumulation of cartilage proteins in the scaffolds, after 7 days of culture (Fig. 8). At the same time, it is also very interesting to see the neo-synthesized matrix spreading around the cells (Fig. 7) because we can expect that, with longer time in culture, the scaffold will be progressively filled with the cartilaginous matrix. Importantly, the neo-synthesized cartilage matrix was already stabilized after 7 days of culture, as attested by the presence of crosslinks between collagen molecules and their organization into a fibrillar network closely associated with proteoglycans (Fig. 9). Moreover, it has already been shown that agarose-encapsulated chondrocytes can synthesize a mechanically functional proteoglycan–collagen matrix.32,33 We also think that agarose is a scaffold of choice to maintain the redifferentiated phenotype since this hydrogel is known to favor a chondrocytic phenotype during long-term culture.34

The objective of our laboratory is to generate a hyaline-like cartilage in vitro before implanting the biological substitute into the joint. The association of chondrocytes, BMP-2, and agarose fits well with this objective. BMP-2 has already been approved for clinical use35,36 and agarose-based hydrogels are considered as clinically potential scaffolds for ACI.37,38 The siRNAs have also been used in several therapies such as for cancer39 and rheumatic diseases.40,41 Biosafety issues are raised with the use of siRNAs, but here, we reported a strategy to overcome the production of type I collagen by delivering siRNA Col1a1 during in vitro cartilage reconstruction. Thus, administration of siRNA in this case is less invasive. Our next objective will be to evaluate the repair potential of this tissue-engineered cartilage in synovial joint defects of large animal models.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Elisabeth Aubert-Foucher and Carole Bougault for their technical assistance. We thank D. Hartmann (Novotec, Lyon, France) for anti-type II and anti-type I collagen antibodies and L. Sandell (St Louis, USA) for anti-type IIA collagen antibody. We are also grateful to SFR BioSciences Gerland-Lyon Sud (US8/UMS3444) for the qPCR experiments. This work was supported by ANR TecSan (PROMOCART 2006), the CNRS-Lyon I University and Rhône-Alpes Region (Cible 2010).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.von der Mark K. Gauss V. von der Mark H. Muller P. Relationship between cell shape and type of collagen synthesised as chondrocytes lose their cartilage phenotype in culture. Nature. 1977;267:531. doi: 10.1038/267531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schindler O.S. Current concepts of articular cartilage repair. Acta Orthop Belg. 2011;77:709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bougault C. Paumier A. Aubert-Foucher E. Mallein-Gerin F. Molecular analysis of chondrocytes cultured in agarose in response to dynamic compression. BMC Biotechnol. 2008;8:71. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-8-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bougault C. Paumier A. Aubert-Foucher E. Mallein-Gerin F. Investigating conversion of mechanical force into biochemical signaling in three-dimensional chondrocyte cultures. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:928. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gouttenoire J. Bougault C. Aubert-Foucher E. Perrier E. Ronziere M.C. Sandell L., et al. BMP-2 and TGF-beta1 differentially control expression of type II procollagen and alpha 10 and alpha 11 integrins in mouse chondrocytes. Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89:307. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gouttenoire J. Valcourt U. Bougault C. Aubert-Foucher E. Arnaud E. Giraud L., et al. Knockdown of the intraflagellar transport protein IFT46 stimulates selective gene expression in mouse chondrocytes and affects early development in zebrafish. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valcourt U. Gouttenoire J. Aubert-Foucher E. Herbage D. Mallein-Gerin F. Alternative splicing of type II procollagen pre-mRNA in chondrocytes is oppositely regulated by BMP-2 and TGF-beta1. FEBS Lett. 2003;545:115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valcourt U. Gouttenoire J. Moustakas A. Herbage D. Mallein-Gerin F. Functions of transforming growth factor-beta family type I receptors and Smad proteins in the hypertrophic maturation and osteoblastic differentiation of chondrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202086200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claus S. Aubert-Foucher E. Demoor M. Camuzeaux B. Paumier A. Piperno M., et al. Chronic exposure of bone morphogenetic protein-2 favors chondrogenic expression in human articular chondrocytes amplified in monolayer cultures. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111:1642. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hautier A. Salentey V. Aubert-Foucher E. Bougault C. Beauchef G. Ronziere M.C., et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates chondrogenic expression in human nasal chondrocytes expanded in vitro. Growth Factors. 2008;26:201. doi: 10.1080/08977190802242488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marlovits S. Hombauer M. Truppe M. Vecsei V. Schlegel W. Changes in the ratio of type-I and type-II collagen expression during monolayer culture of human chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:286. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b2.14918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darling E.M. Athanasiou K.A. Growth factor impact on articular cartilage subpopulations. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:463. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narcisi R. Quarto R. Ulivi V. Muraglia A. Molfetta L. Giannoni P. TGF beta-1 administration during ex-vivo expansion of human articular chondrocytes in a serum-free medium redirects the cell phenotype toward hypertrophy. J Cell Physiol. 2011;227:3282. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefebvre V. Garofalo S. Zhou G. Metsaranta M. Vuorio E. De Crombrugghe B. Characterization of primary cultures of chondrocytes from type II collagen/beta-galactosidase transgenic mice. Matrix Biol. 1994;14:329. doi: 10.1016/0945-053x(94)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfaffl M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claus S. Mayer N. Aubert-Foucher E. Chajra H. Perrier-Groult E. Lafont J., et al. Cartilage-characteristic matrix reconstruction by sequential addition of soluble factors during expansion of human articular chondrocytes and their cultivation in collagen sponges. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2012;18:104. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2011.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallein-Gerin F. Ruggiero F. Quinn T.M. Bard F. Grodzinsky A.J. Olsen B.R., et al. Analysis of collagen synthesis and assembly in culture by immortalized mouse chondrocytes in the presence or absence of alpha 1(IX) collagen chains. Exp Cell Res. 1995;219:257. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid T.M. Linsenmayer T.F. Immunohistochemical localization of short chain cartilage collagen (type X) in avian tissues. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:598. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.2.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruckner P. Mendler M. Steinmann B. Huber S. Winterhalter K.H. The structure of human collagen type IX and its organization in fetal and infant cartilage fibrils. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefebvre V. Huang W. Harley V.R. Goodfellow P.N. de Crombrugghe B. SOX9 is a potent activator of the chondrocyte-specific enhancer of the pro alpha1(II) collagen gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2336. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole C.A. Flint M.H. Beaumont B.W. Chondrons in cartilage: ultrastructural analysis of the pericellular microenvironment in adult human articular cartilages. J Orthop Res. 1987;5:509. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100050406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canty E.G. Kadler K.E. Procollagen trafficking, processing and fibrillogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1341. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart M.C. Saunders K.M. Burton-Wurster N. Macleod J.N. Phenotypic stability of articular chondrocytes in vitro: the effects of culture models, bone morphogenetic protein 2, and serum supplementation. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:166. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Millington-Ward S. McMahon H.P. Allen D. Tuohy G. Kiang A.S. Palfi A., et al. RNAi of COL1A1 in mesenchymal progenitor cells. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:864. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q. Peng Z. Xiao S. Geng S. Yuan J. Li Z. RNAi-mediated inhibition of COL1A1 and COL3A1 in human skin fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:611. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao Y. Zhang F. Pang P.X. Su K. Zhou R. Wang Y., et al. In vitro study of chondrocyte redifferentiation with lentiviral vector-mediated transgenic TGF-beta3 and shRNA suppressing type I collagen in three-dimensional culture. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;5:e219. doi: 10.1002/term.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao Y. Zhang F. Zhou R. Su K. Fan J. Wang D.A. Effects of combinational adenoviral vector-mediated TGF beta 3 transgene and shRNA silencing type I collagen on articular chondrogenesis of synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;106:818. doi: 10.1002/bit.22733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han S. Makareeva E. Kuznetsova N.V. DeRidder A.M. Sutter M.B. Losert W., et al. Molecular mechanism of type I collagen homotrimer resistance to mammalian collagenases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han S. McBride D.J. Losert W. Leikin S. Segregation of type I collagen homo- and heterotrimers in fibrils. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:122. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jimenez S.A. Bashey R.I. Benditt M. Yankowski R. Identification of collagen alpha1(I) trimer in embryonic chick tendons and calvaria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1977;78:1354. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)91441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moro L. Smith B.D. Identification of collagen alpha1(I) trimer and normal type I collagen in a polyoma virus-induced mouse tumor. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;182:33. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buschmann M.D. Gluzband Y.A. Grodzinsky A.J. Kimura J.H. Hunziker E.B. Chondrocytes in agarose culture synthesize a mechanically functional extracellular matrix. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:745. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mauck R.L. Soltz M.A. Wang C.C. Wong D.D. Chao P.H. Valhmu W.B., et al. Functional tissue engineering of articular cartilage through dynamic loading of chondrocyte-seeded agarose gels. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:252. doi: 10.1115/1.429656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benya P.D. Shaffer J.D. Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels. Cell. 1982;30:215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Govender S. Csimma C. Genant H.K. Valentin-Opran A. Amit Y. Arbel R., et al. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 for treatment of open tibial fractures: a prospective, controlled, randomized study of four hundred and fifty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:2123. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landry Y. Gies J.P. Drugs and their molecular targets: an updated overview. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barlic A. Drobnic M. Malicev E. Kregar-Velikonja N. Quantitative analysis of gene expression in human articular chondrocytes assigned for autologous implantation. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:847. doi: 10.1002/jor.20559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selmi T.A. Verdonk P. Chambat P. Dubrana F. Potel J.F. Barnouin L., et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in a novel alginate-agarose hydrogel: outcome at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:597. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B5.20360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Z. Rao D.D. Senzer N. Nemunaitis J. RNA interference and cancer therapy. Pharm Res. 2011;28:2983. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Franca N.R. Mesquita Junior D. Lima A.B. Pucci F.V. Andrade L.E. Silva N.P. RNA interference: a new alternative for rheumatic diseases therapy. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2010;50:695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huber L.C. Distler O. Gay R.E. Gay S. Antisense strategies in degenerative joint diseases: sense or nonsense? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:285. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salvat C. Pigenet A. Humbert L. Berenbaum F. Thirion S. Immature murine articular chondrocytes in primary culture: a new tool for investigating cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:243. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cormier S.A. Mello M.A. Kappen C. Normal proliferation and differentiation of Hoxc-8 transgenic chondrocytes in vitro. BMC Dev Biol. 2003;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang Z. Xu H. Sandell L. Negative regulation of chondrocyte differentiation by transcription factor AP-2alpha. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:245. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2004.19.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valcourt U. Ronziere M.C. Winkler P. Rosen V. Herbage D. Mallein-Gerin F. Different effects of bone morphogenetic proteins 2, 4, 12, and 13 on the expression of cartilage and bone markers in the MC615 chondrocyte cell line. Exp Cell Res. 1999;251:264. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayne R. Mayne P.M. Ren Z. Accavitti M.A. Gurusiddappa S. Scott P.G. Monoclonal antibody to the aminotelopeptide of type II collagen: loss of the epitope after stromelysin digestion. Connect Tissue Res. 1994;31:11. doi: 10.3109/03008209409005631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oganesian A. Zhu Y. Sandell L.J. Type IIA procollagen amino propeptide is localized in human embryonic tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:1469. doi: 10.1177/002215549704501104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warman M. Kimura T. Muragaki Y. Castagnola P. Tamei H. Iwata K., et al. Monoclonal antibodies against two epitopes in the human alpha 1 (IX) collagen chain. Matrix. 1993;13:149. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]