Abstract

Objectives

Casual review of existing literature reveals a multitude of individualized approaches to emergency department (ED) HIV testing. Cataloging the operational options of each approach could assist translation by disseminating existing knowledge, endorsing variability as a means to address testing barriers, and laying a foundation for future work in the area of operational models and outcomes investigation. The objective of this study is to provide a detailed account of the various models and operational constructs that have been described for performing HIV testing in EDs.

Methods

Systematic review of PUBMED, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the Web of Science through February 6, 2009 was performed. Three investigators independently reviewed all potential abstracts and identified all studies that met the following criteria for inclusion: original research, performance of HIV testing in an ED in the United States, description of operational methods, and reporting of specific testing outcomes. Each study was independently assessed and data from each were abstracted with standardized instruments. Summary and pooled descriptive statistics were reported by using recently published nomenclature and definitions for ED HIV testing.

Results

The primary search yielded 947 potential studies, of which 25 (3%) were included in the final analysis. Of the 25 included studies, 13 (52%) reported results using nontargeted screening as the only patient selection method. Most programs reported using voluntary, opt-in consent and separate, signed consent forms. A variety of assays and communication methods were used, but relatively limited outcomes data were reported.

Conclusion

Currently, limited evidence exists to inform HIV testing practices in EDs. There appears to be recent progression toward the use of rapid assays and nontargeted patient selection methods, with the rate at which reports are published in the peer-reviewed literature increasing. Additional research will be required, including controlled clinical trials, more structured program evaluation, and a focus on an expanded profile of outcome measures, to further improve our understanding of which HIV testing methods are most effective in the ED.

Introduction

Background

Approximately 230,000 people in the United States have an undiagnosed HIV infection, and it is estimated that 56,300 become newly infected each year.1,2 An important approach to prevention of HIV infection includes early identification of existing disease. Much of the effort directed toward earlier diagnosis has focused on expanding HIV testing in emergency departments (EDs) because they are thought to serve as important clinical venues to perform these activities.3,4

Importance

Testing for HIV infection in EDs has been categorized into the following distinct and mutually exclusive testing approaches: diagnostic testing, targeted screening, and nontargeted screening.3 Our understanding of ED HIV testing has been advanced by the many investigators who have reported data from various practice models. Unfortunately, relatively little is known about which method or methods are most feasible or effective in this unique clinical setting or the relative ways in which testing may affect other ED processes of care.

Goals of This Investigation

The objective of this study was therefore to provide a detailed account of the various methods and operational constructs that have been described for performing HIV testing in EDs as the initial step to allowing comparisons between approaches.

Methods

This project included only aggregate data from previously published work. As such, no institutional review board approval was necessary. The reporting of this systematic review was prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.5

Search Strategy

To identify previous publications related to performing HIV testing in EDs, we performed systematic searches of several publication search engines, including PubMed (MEDLINE), EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the Web of Science. To identify all ED-related HIV testing publications from the beginning of each database to the present, we used the following search criteria: “hiv” or “human immunodeficiency virus,” and “diagnosis,” “testing” or “screening,” and “emergency department,” “emergency room,” “emergency ward,” or “emergency medical services.” In addition, all participants of the 2007 National Emergency Department HIV Testing Consortium consensus conference were individually searched by name to identify any other published work.

Inclusion Criteria

We considered publications eligible for review if they included original research, performance of HIV testing in an ED in the United States, description of operational methods, and reporting of specific testing outcomes.

Publication Selection

All titles and abstracts from identified publications were screened in a blinded fashion for eligibility by 3 independent reviewers (J.S.H., D.A.E.W., and M.S.L.). All publications considered potentially relevant were retained and the full articles were reviewed for inclusion. Of the full articles selected for inclusion, all references were also manually searched to ensure inclusion of all relevant publications.

Assessment of Quality

The validity of study designs included in this synthesis was not formally assessed because of the variety of designs and because most were primarily descriptive.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Four reviewers (J.S.H., D.A.E.W., M.S.L., and R.E.R.) independently abstracted data in duplicate from each article, using a structured data collection instrument. The data collection instrument included sections related to the 4 “Core Theoretical Constructs” related to the reporting of HIV testing activities in EDs, as reported in Lyons et al6 in 2008. These constructs included (1) setting (geography and epidemiology, facility, and HIV testing program); (2) recruitment and consent (patient selection strategies and criteria, HIV consent, default assumption of patient willingness to undergo testing, patient awareness of right not to undergo testing, patient identification of willingness to be tested, and integration with consent process for general medical care); (3) postconsent program methods (testing and assay, preresult communication, and postresult communication and methods); and (4) outcomes. Outcomes included total number of eligible patients, total number offered HIV testing, total number who received HIV testing, total confirmed positive results, total number of patients linked to care, and mean or median CD4 counts for those who received a confirmed positive result.

Data Management and Statistical Analyses

All data were entered into an electronic database (Microsoft Access; Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and transferred into SAS format with translational software (df/Power DBMS/Copy; DataFlux, Cary, NC). All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All data were cleaned, and discrepancies identified during the dual abstraction were resolved with an adjudication process that involved reabstraction of the discrepant variables by another investigator (E.H.). Descriptive statistics are reported for all variables. Continuous data are reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and categorical data are reported as percentages with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

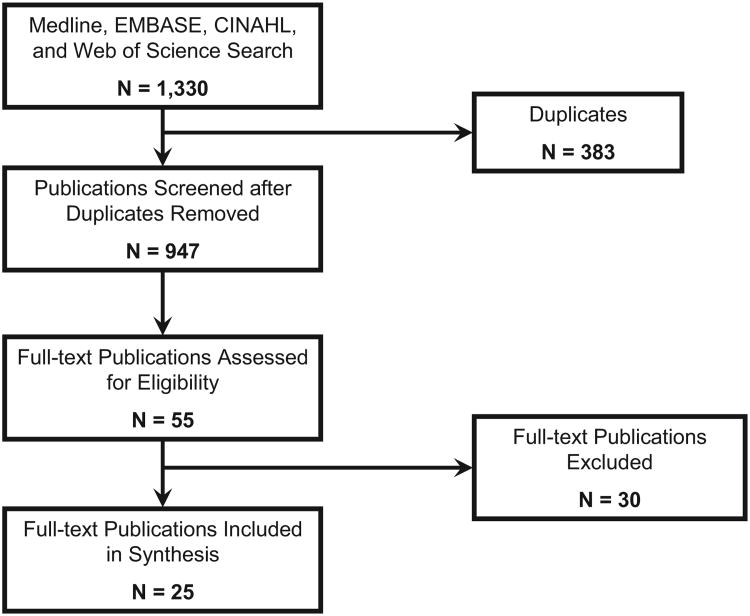

The primary search yielded 947 unique publications. Of these, 55 (6%) were identified for further evaluation after abstract screening. Of the 55 articles, 25 (46%) met criteria for inclusion after complete review and represent the sample used for this synthesis (Figure). All included publications ranged from 1992 through 2009.7-31

Figure.

Flow diagram of selection process of included articles.

Of the 25 included publications, 12 (48%) resulted from the Northeast, 5 (20%) from the Midwest, 5 (20%) from the West, and 3 (12%) from the South. Additionally, all 22 (100%) of the publications that reported a setting were categorized as urban, and of the 13 publications that reported the type of institution, 12 (92%) described their institutions as academic or teaching, and only 1 (8%) publication reported its institution as community based. Of the 19 institutions that reported annual ED census data, the median census was 55,000 patient visits (IQR 44,000 to 95,000 patient visits). Of the 13 publications that reported funding to support their programs, all (100%) reported having received external funding.

Of the 25 included publications, 1 (4%) reported performing diagnostic testing only, 2 (8%) reported performing targeted screening only, 13 (52%) reported performing nontargeted screening only, 8 (32%) reported performing a combination of testing methods, and 1 (4%) did not report an explicit patient selection method.

Table 1 describes staffing and consent methods stratified by different HIV testing approaches. Of the 23 publications that reported general consent methods, 22 (96%) used a voluntary approach. Of the 21 publications that reported a distinction between using opt-in versus opt-out approaches, 20 (95%) used an opt-in approach. Of the 15 publications that reported using verbal or signed consent, all (100%) used signed consent, and of the 21 publications that reported using integrated or separate consent documentation, 20 (95%) used separate documentation. Last, of the 13 publications that reported solely performing nontargeted screening, only 1 (8%) used an opt-out approach.

Table 1.

Staffing and consent methods of HIV testing models performed in the ED.*

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Diagnostic Testing Only (N=1) | Targeted Screening Only (N=2) | Nontargeted Screening Only (N=13) | Combination (N=8) | |

| Staffing | ||||

| Native | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 3 (23) | 3 (38) |

| Exogenous | 0 | 1 (50) | 7 (54) | 1 (12) |

| Combined | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 4 (50) |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Consent | ||||

| Mandatory | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12) |

| Voluntary | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 13 (100) | 6 (75) |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12) |

| Opt in | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 12 (92) | 5 (63) |

| Opt out | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (37) |

| Implicit | 0 | 0 | 4 (31) | 0 |

| Explicit | 1 (100) | 0 | 3 (23) | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 2 (100) | 6 (46) | 8 (100) |

| Verbal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Signed | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 7 (54) | 5 (63) |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 6 (46) | 3 (37) |

| Integrated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12) |

| Separate | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 12 (92) | 5 (63) |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 2 (25) |

A total of 25 publications met criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. However, one did not report an explicit patient selection method and therefore was not included in this table.

Table 2 describes assay methods stratified by different HIV testing approaches. Of the 18 publications that reported using either blood or saliva, 11 (61%) used blood as the only source of testing and all (100%) reported using venipuncture as the method of obtaining blood. Of the 21 publications that reported using rapid or conventional assays, 10 (48%) used rapid assays only, 7 (33%) used conventional assays only, and 2 (10%) used a combination of the 2 assays. None of the publications reported using antigen-based or nucleic acid–based testing. Of the 13 publications that reported the site of performing the assay, 4 (31%) used an external laboratory, 3 (23%) performed the assay at the patient's bedside, 2 (15%) used an ED-based laboratory, 2 (15%) used the hospital's laboratory, and 2 (15%) used a combination of these approaches.

Table 2.

Assay methods of HIV testing models performed in the ED.*

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Diagnostic Testing Only (N=1) | Targeted Screening Only (N=2) | Nontargeted Screening Only (N=13) | Combination (N=8) | |

| Blood only | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 3 (23) | 5 (63) |

| Saliva only | 0 | 0 | 3 (23) | 2 (25) |

| Both | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 5 (39) | 1 (12) |

| Oral swab only | 0 | 0 | 3 (23) | 2 (25) |

| Fingerstick only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Venipuncture only | 0 | 2 (100) | 3 (23) | 5 (63) |

| Combination | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 0 |

| Not reported | 1 (100) | 0 | 5 (39) | 1 (12) |

| Rapid only | 1 (100) | 0 | 7 (54) | 2 (25) |

| Conventional only | 0 | 2 (100) | 2 (15) | 5 (63) |

| Both | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 1 (12) |

| Antibody | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 10 (77) | 7 (88) |

| Antigen | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nucleic acid | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 3 (23) | 1 (12) |

| POC bedside only | 0 | 0 | 3 (23) | 0 |

| POC ED only | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 1 (12) |

| Laboratory only | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 | 1 (12) |

| External lab only | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 2 (25) |

| Combination | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 1 (12) |

| Not reported | 0 | 2 (100) | 6 (46) | 3 (38) |

| WB confirmation | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 10 (77) | 8 (100) |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (50) | 3 (23) | 0 |

POC, Point of care; WB, Western blot.

A total of 25 publications met criteria for inclusion in the systematic review. However, one did not report an explicit patient selection method and was therefore not included in this table.

Table 3 describes methods of preresult and postresult communication and linkage to care stratified by different HIV testing approaches. Of the 20 publications that reported preresult communication methods, 7 (35%) used prevention counseling, only 6 (30%) provided information only, and 6 (30%) used a combination of the 2 methods. Similarly, of the 15 publications that reported postresult communication methods, 9 (60%) used prevention counseling only, 2 (13%) provided information only, and 4 (27%) used a combination of the 2 methods. Additionally, of the 21 publications that reported when postresult communication was provided, 12 (57%) provided it after ED discharge only, 7 (33%) provided it during the ED visit only, and 2 (10%) reported providing a combination. All 12 publications that reported performing postresult communication after ED discharge also performed conventional HIV testing. Furthermore, in-person communication and active linkage to care were performed in the majority of programs.

Table 3.

Communication and linkage-to-care methods of HIV testing models performed in the ED.*

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Diagnostic Testing Only (N=1) | Targeted Screening Only (N=2) | Nontargeted Screening Only (N=13) | Combination (N=8) | |

| Preresult communication | ||||

| Information only | 0 | 0 | 5 (38) | 1 (12) |

| Education only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Counseling only | 0 | 1 (50) | 1 (8) | 5 (63) |

| Combination | 1 (100) | 0 | 4 (31) | 1 (12) |

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12) |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (50) | 3 (23) | 0 |

| Postresult communication | n | |||

| Information only | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 0 |

| Education only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Counseling only | 0 | 2 (100) | 4 (31) | 3 (38) |

| Combination | 1 (100) | 0 | 2 (15) | 1 (12) |

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 5 (38) | 4 (50) |

| Physician only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nurse only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Counselor only | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 3 (38) |

| Social worker only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 3 (23) | 0 |

| Combination | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (15) | 2 (25) |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (50) | 7 (53) | 3 (38) |

| In ED only | 1 (100) | 0 | 4 (31) | 2 (25) |

| After discharge Only | 0 | 2 (100) | 4 (31) | 6 (75) |

| Both | 0 | 0 | 2 (15) | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 | 3 (23) | 0 |

| In person only | 1 (100) | 0 | 9 (69) | 5 (63) |

| By mail only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| By telephone only | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Combination | 0 | 1 (50) | 1 (8) | 1 (12) |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (50) | 3 (23) | 2 (25) |

| Linkage | ||||

| Active only | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 4 (31) | 4 (50) |

| Passive only | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Both | 0 | 0 | 1 (7) | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (50) | 7 (54) | 4 (50) |

A total of 25 publications met criteria for inclusion in the systematic review. However, one did not report an explicit patient selection method and therefore was not included in this table.

Table 4 describes the reported outcomes stratified by different HIV testing approaches. Relative to the other 2 testing approaches (diagnostic testing and targeted screening), nontargeted screening resulted in a larger number of patients being offered testing yet a similar number of patients receiving a diagnosis of HIV infection.

Table 4.

Reported outcomes of HIV testing models performed in the ED.*

| Diagnostic Testing Only (N=1) Median (IQR) | Targeted Screening Only (N=2) Median (IQR) | Nontargeted Screening Only (N=13) Median (IQR) | Combination (N=8) Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible patients | 0 (0) | 537 (200–873) | 3,030 (2,155–13,240) | 32,121 (5,285–118,324) |

| Offered HIV testing | 0 (0) | 200 (†) | 3,030 (2,356–4,187) | 1,287 (494–8,574) |

| Received HIV testing | 681 (†) | 177 (168–186) | 1,438 (944–2,293) | 860 (187–4,371) |

| Confirmed positive | 15 (†) | 24 (†) | 9 (6–55) | 15 (4–83) |

| Linked to care | 12 (†) | 6 (†) | 19 (4–26) | 22 (7–61) |

| CD4 count | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 503 (†) | 0 (0) |

A total of 25 publications met criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. However, one did not report an explicit patient selection method and therefore was not included in this table.

Represents 1 study.

Limitations

The results of this study are limited by the relatively small number of studies focused in academic settings. As such, the ability to make comparisons and to determine effectiveness of various approaches and operational methods was not possible, and therefore the results are not easily generalizable to the thousands of community-based EDs in the United States. Given the heterogeneous nature of the publications included, we were also not able to combine studies in such a way as to make direct comparisons between operational methods and outcomes.

The primary limitation of this project is inherent to the literature base reviewed. A finding of our review was that publications to date may not, in the aggregate, be generalizable, comprehensive, or fully interpretable. Beyond this, it is possible the synthesis was limited by selection bias. Although we used a systematic approach to identification of publications, it is possible 1 or more relevant articles were not included. Additionally, it is possible that misclassification bias was introduced during the abstraction process, although our approach was designed to minimize this possibility.

Discussion

This article represents work initiated during the 2007 Conference of the National Emergency Department HIV Testing Consortium, held in Baltimore, MD, on November 12, 2007. To our knowledge, this represents the first attempt to systematically synthesize operational aspects of performing HIV testing in the ED. In doing so, we hope it will assist in translation of HIV testing practices by disseminating existing knowledge, endorsing variability as a means to address testing barriers, and laying a foundation for future investigations in the area of operational models and outcomes.

Operational HIV Testing Models Not Fully Characterized

Overall, a relatively small number of programs were included in this synthesis and all but 1 resulted from an academic setting. In addition, the majority of publications included in this study occurred after 2003 and most occurred after 2006, with all but 2 of the studies representing observational research. As such, the overall generalizability of the findings is relatively limited.

The performance of HIV testing in the ED has received substantial attention during the past several years, and an acceleration of work in this area occurred after the release of the 2006 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for HIV testing in health care settings.32,33 With a small but growing experience and relatively little comparative evidence, investigators have primarily developed testing programs de novo. After review of the articles, it became implicitly or explicitly apparent that most HIV testing methods were developed or selected after consideration of specific testing barriers present within a given practice setting. Although these early studies provided new insights about HIV testing practices, as the evidence base grows, it is increasingly likely that new programs will adopt testing methods from previously reported work, rather than independently designing novel methods in response to individualized practice circumstances.

Of the 25 reported studies, only 1 reported and detailed performing exclusively diagnostic testing and only 2 reported and detailed performing exclusively targeted screening. Although emphasis on nontargeted screening has occurred during the past several years in response primarily to the current CDC recommendations, the former 2 testing strategies remain important and relatively unevaluated in the ED setting. In fact, some have advocated that diagnostic testing serve as the minimum HIV testing standard of care in the ED, but given the relatively few studies, others may view this contention as uncertain.34 Additionally, targeted screening remains relatively unevaluated in the ED setting. Given that nontargeted screening in the ED is relatively resource intensive, targeted screening may serve as a more effective approach. Comparative clinical trials of targeted screening versus nontargeted screening have not been performed to date, and unfortunately, little is known about how best to target patients in this unique clinical setting.9,10

Individual Operational Details Within HIV Testing Models

Using a template adopted from Lyons et al6 for the reporting of HIV testing programs, we found that a relatively large proportion of individual studies lacked relevant details about operational methods used, making it difficult to make meaningful comparisons between different testing approaches or within approaches that use the same patient selection strategies. This relative lack of information highlights the need to improve our understanding of which testing methods are most effective in the emergency care setting and suggests the need for more structured research, including the performance of prospective controlled clinical trials.

Nearly all testing programs used a voluntary, opt-in consent approach with separate signed consent forms. The current recommendation by the CDC, to use an opt-out approach and to integrate consent into the general consent process in the ED, has not yet been widely studied. Although several studies are being conducted and will likely inform our practices relative to obtaining consent for HIV testing, none were included in this synthesis. Therefore, the optimal approach to obtaining consent remains uncertain, especially in the context of patient understanding and acceptance and the process by which consent is obtained in the ED.

A variety of HIV testing and communication approaches were also reported by studies included in this review, including both rapid and conventional testing. With the introduction of highly accurate rapid assays, conventional testing now appears to be less common. The ED environment, including its acute episodic nature and relative lack of structured follow-up, lends itself more to using rapid assays as the primary means of performing HIV testing. Additionally, most communication methods included prevention counseling, consistent with HIV testing recommendations before 2006. As attempts have been made to mitigate barriers particular to performing HIV testing in EDs, use of pretest information or educational videos and limited postresult counseling has been emphasized. Although Calderon et al19,24,35 and Merchant et al31 have published work related to use of educational videos in the setting of ED-based HIV testing, relatively little additional research has been published that describes how best to integrate these aspects into operational models.

A variety of staffing approaches were reported, although a large proportion of models used external staff to perform HIV testing in the ED. The ability to integrate HIV testing into EDs using native or external staff will likely depend heavily on how testing is funded. Although most testing models have been developed and evaluated in academic settings, it is clear that to integrate HIV testing and screening into community-based EDs, use of native staff will be required. As such, additional research and experience with using native staff to implement different testing models will be needed.

This synthesis highlights the need for future controlled clinical trials and more rigorous comparative effectiveness and program evaluation studies to determine which unique operational methods are most effective and whether unique models of testing are most effective and efficient relative to emergency medical care.

Future Directions

To facilitate the adoption of operational models described in the literature, there appear to be 2 primary unmet needs. First, the literature base needs to be more standardized and clarified. In this systematic review, there were many instances in which it was questionable whether terms used identically in different articles actually referred to precisely the same operational practice. Recently published consensus standards for nomenclature and definitions should assist in this effort, although a standardized approach to the reporting of operational methods based on consensus-based reporting guidelines is still needed. Such consensus guidelines are being developed in conjunction with the National ED HIV Testing Consortium. Second, there is a need for improved understanding of which operational models are most effective. This can be accomplished through comparative study of operational methods, within and between settings, and through use of a standard set of outcomes.

Conclusion

Currently, limited evidence exists to inform HIV testing practices in EDs. There appears to be recent progression toward the use of rapid assays and nontargeted patient selection methods, with the rate at which reports are published in the peer-reviewed literature increasing. Additional research including controlled clinical trials, more structured program evaluation, and a focus on an expanded profile of outcome measures will be required to further improve our understanding of which HIV testing methods are most effective in the ED.

Acknowledgments

Funding and support: By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). This work was supported, in part, by an Independent Scientist Award (K02 HS017526) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and a cooperative agreement (U18 PS000314) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to Dr. Haukoos; a cooperative agreement (U18 PS000321) from the CDC to Dr. White; a mentored, patient-oriented career development award (K23 AI068453) from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases to Dr. Lyons; a mentored, patient-oriented career development award (K23 HD054315) from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to Dr. Calderon; and a grant from the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to Dr. Rothman. The 2007 Conference of the National Emergency Department HIV Testing Consortium was supported by an unrestricted grant from Gilead Sciences, Inc. and with organizational support from the Health Research and Educational Trust of the American Hospital Association.

Publication of this article was supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.

Appendix

The authors acknowledge all participants of the 2007 Conference of the National Emergency Department HIV Testing Consortium: Chris Aldridge, MD; Gregory Almond, MD, MPH, MS; Roberto Andrade, MD; Christian Arbelaez, MD, MPH; Tom-meka Archinard, MD; Steven I. Aronin, MD; Susan Barrera; Moses Bateganya, MD; Joanna Bell-Merriam, MD; Bob Bongiovanni; Kathleen Brady, MD; Bernard Branson, MD; Carol Brosgart, MD; Jeremy Brown, MD; Evan Cadoff, MD; Linda M. Chaille-Arnold, MD; Ben Cheng, MSc; William Chiang, MD; Brittney Copeland; Rosalyn L. Cousar, RN, PhD, AACRN; Eileen Couture, DO, MS; Maggie Czarnogorski, MD; Kit Delgado, MD; Emily Erbelding, MD, MPH; James Feldman, MD, MPH; Osvaldo Garcia; Charlotte A. Gaydos, MS, MPH; Nancy Glick, MD; Barbara Gripshover, MD; Alisa Hayes, MD; James Heffelfinger, MD, MPH; Laura Herrera, MD, MPH; Amy Hilley, MPH; David Holtgrave, PhD; Brooke Hoots, MSPH; Debra Houry, MD, MPH; Larry Howell; Yu-Hsiang Hsieh, PhD; Angela B. Hutchinson, PhD, MPH; Blanca Jackson, RN; Michael Jaker, MD; Kerin Jones, MD; Juliana Jung, MD; Linda Kampe, BA; Virginia Kan, MD; Nancy Kass, ScD; Gabor D. Kelen, MD; Karen Kroc, BS; Ann Kurth, PhD, RN; Margaret A. Lampe, RN, MPH; Jason Leider, MD, PhD; Michael Lemanski, MD; Christopher J. Lindsell, PhD; Sandra McGovern, RN; Seth Mercer, MD; Roland Merchant, MD, MPH, ScD; Nancy Miertschin, MPH; Joan Miller; Patricia Mitchell, RN; Sarah Nelson, FNP; Linda Onaga, MPH; David Paltiel, PhD; Sindy M. Paul, MD, MPH; Harold Pollack, PhD; Stephen Raffanti, MD, MPH; Liisa Randall, PhD; Akhter Sabreen, DO; Jeffrey Sankoff, MD; Vanessa Sasso; Nathaniel Bernard Saylor, MD; Elissa Schechter, MD; Barbara Schechtman, MPH; Steven Schrantz, MD; Alicia Scribner, MPH; Judy Shahan, RN, MBA; Daniel Skiest, MD; Freya Spielberg, MD, MPH; Irijah S. Stennett, PA; Patrick Sullivan, DVM, PhD; Cathalene Teahan, RN, MSN, CNS; Susan Thompson; Gretchen Torres, MPP; Vicken Totten, MD; Krystn Wagner, MD; Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH; Michael Waxman, MD; Andrea Weddle; Douglas White, MD; Tom Widell, MD; James A. Wilde, MD; Keith Wrenn, MD; Juliet Yonek.

Footnotes

All attendees from the 2007 conference are listed in the Appendix.

Contributor Information

Jason S. Haukoos, Department of Emergency Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, Denver, CO; University of Colorado School of Medicine and the Department of Epidemiology, Colorado School of Public Health, Aurora, CO.

Douglas A. E. White, Department of Emergency Medicine, Alameda County Medical Center, Highland Hospital, Oakland, CA.

Michael S. Lyons, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH.

Emily Hopkins, Department of Emergency Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, Denver, CO.

Yvette Calderon, Department of Emergency Medicine, Jacobi Medical Center, and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY.

Brian Kalish, Maryland State Health Department, Baltimore, MD; Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

Richard E. Rothman, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevalence estimates—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothman RE, Lyons MS, Haukoos JS. Uncovering HIV infection in the emergency department: a broader perspective. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:653–657. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein SL, Haukoos JS. Public health, prevention, and emergency medicine: a critical juxtaposition. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:190–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. [Accessed March 30,2011];BMJ. 2009 339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2714672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Haukoos JS, et al. Nomenclature and definitions for emergency department human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing: report from the 2007 conference of the National Emergency Department HIV Testing Consortium. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:168–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behrens JJ, Stannard JP, Bucknell AL. The prevalence of seropositivity for human immunodeficiency virus in patients who have severe trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:641–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindsay MK, Grant J, Peterson HB, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection among patients in a gynecology emergency department. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:1012–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelen GD, Hexter DA, Hansen KN, et al. Feasibility of an emergency department-based, risk-targeted voluntary HIV screening program. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:687–692. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelen GD, Shahan JB, Quinn TC, et al. Emergency department– based HIV screening and counseling: experience with rapid and standard serologic testing. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goggin MA, DAvidson AJ, Cantrill SV, et al. The extent of undiagnosed HIV infection among emergency department patients: results of a blinded seroprevalence survey and a pilot HIV testing program. J Emerg Med. 2000;19:13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(00)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Routinely recommended HIV testing at an urban urgent-care clinic—Atlanta, Georgia, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;(50):538–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beckmann KR, Melzer-Lange MD, Cuene B, et al. The effectiveness of a follow-up program at improving HIV testing in a pediatric emergency department. WMJ. 2002;101:30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coil CJ, Haukoos JS, Witt MD, et al. Evaluation of an emergency department referral system for outpatient HIV testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35:52–55. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glick NR, Silva A, Zun L, et al. HIV testing in a resource-poor urban emergency department. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:126–136. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.2.126.29391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendrick SR, Kroc KA, Couture E, et al. Comparison of point-of-care rapid HIV testing in three clinical venues. AIDS. 2004;18:2208–2210. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411050-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ledyard HK, et al. Emergency department HIV testing and counseling: an ongoing experience in a low-prevalence area. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haukoos JS, Witt MD, Coil CJ, et al. The effect of financial incentives on adherence with outpatient human immunodeficiency virus testing referrals from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:617–621. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calderon Y, Haughey M, Bijur PE, et al. An educational HIV pretest counseling video program for off-hours testing in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva A, Glick NR, Lyss SB, et al. Implementing an HIV and sexually transmitted disease screening program in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyss SB, Branson BM, Kroc KA, et al. Detecting unsuspected HIV infection with a rapid whole-blood HIV test in an urban emergency department. J Aquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:435–442. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f83d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta SD, Hall J, Lyss SB, et al. Adult and pediatric emergency department sexually transmitted disease and HIV screening: programmatic overview and outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:250–258. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telzak E, Grumm F, Coffey J, et al. Rapid HIV testing in emergency departments three US sites, January 2005–March 2006. JAMA. 2007;298:395–397. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calderon Y, Haughey M, Leider J, et al. Increasing willingness to be tested for human immunodeficiency virus in the emergency department during off-hour tours: a randomized trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:1025–1029. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31814b96bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Eliopoulos VT, et al. Development and implementation of a model to improve identification of patients infected with HIV using diagnostic rapid testing in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:1149–1157. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown J, Shesser R, Simon G, et al. Routine HIV screening in the emergency department using the new US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines: results from a high-prevalence area. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:395–401. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181582d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mollen C, Lavelle J, Hawkins L, et al. Description of a novel pediatric emergency department-based HIV screening program for adolescents. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:505–512. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walensky RP, Arbelaez C, Reichmann WM, et al. Revising expectations from rapid HIV tests in the emergency department. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:153–160. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-3-200808050-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White DA, Scribner AN, Schulden JD, et al. Results of a rapid HIV screening and diagnostic testing program in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;54:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merchant RC, Seage GR, Mayer KH, et al. Emergency department patient acceptance of opt-in, universal, rapid HIV screening. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(suppl 3):27–40. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merchant RC, Clark MA, Mayer KH, et al. Video as an effective method to deliver pre-test information for rapid human immunodeficiency testing. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:124–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–17. quiz CE1-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haukoos JS, Lyons MS. Idealized models or incremental program evaluation: translating emergency department HIV testing into practice. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1044–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Byyny RL, et al. Design and implementation of a controlled clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of routine opt-out rapid human immunodeficiency virus screening in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:800–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calderon Y, Haughey M, Bijur P, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the educational effectiveness of a rapid human immunodeficiency virus post-test counseling video. Presented at: 2006 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine annual meeting; May 18-21, 2006; San Francisco, CA. p. S22. [Google Scholar]