Abstract

Cigarette smokers and substance users discount the value of delayed outcomes more steeply than non-users. Higher discounting rates are associated with relapse and poorer treatment outcomes. The left dorsolateral prefontal cortex (DLPFC) exerts an inhibitory influence on impulsive or seductive choices and greater activity in the prefrontal cortex is associated with lower discounting rates. We hypothesized that increasing activity in the left DLPFC with high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (HF rTMS) would decrease delay discounting and decrease impulsive decision-making in a gambling task as well as decrease cigarette consumption, similar to other studies. In this single-blind, within-subjects design, smokers with no intention to quit (n=47) and nonsmokers (n=19) underwent three counterbalanced sessions of HF rTMS (20Hz, 10Hz, sham) delivered over the left DLPFC. Tasks were administered at baseline and after each stimulation session. Stimulation decreased discounting of monetary gains (F[3,250]=4.46, p<.01), but increased discounting of monetary losses (F[3,246]=4.30, p<.01), producing a reflection effect, normally absent in delay discounting. Stimulation had no effect on cigarette consumption. These findings provide new insights into cognitive processes involved with decision-making and cigarette consumption and suggest that like all medications for substance dependence, HF rTMS is likely to be most effective when paired with cognitive-behavioral interventions.

Keywords: transcranial magnetic stimulation, delay discounting, smoking cessation

Tobacco use is the single largest preventable cause of death and disease in the US today. Most smokers want to quit; half of all smokers make a quit attempt each year, but 95% of those who attempt will reverse this decision and relapse within 12 months. Like all substance use disorders, neuroadaptations following drug exposure are thought to underlie tobacco addiction, but this does not fully explain or account for addiction as a chronic relapsing disorder. New approaches are needed to understand the decision-making processes involved with tobacco addiction and other addictive disorders. Neuromodulation is a novel approach to understanding these processes as well as developing interventions for smoking and other addictive disorders.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) has a complex, dynamic role in decision-making processes and in the abnormal decision-making processes of persons addicted to substances. Witness the common situation in which substance dependent individuals repeatedly choose the transient, immediately rewarding activity of drug or tobacco use at the cost of larger long-term rewards such as long life, health, and relationships often to the dismay and confusion of family, friends, and treatment providers. The DLPFC is believed to influence decision-making by exerting an inhibitory influence on emotionally charged, impulsive, and/or immediately rewarding choice options.

Delay discounting is a well-studied type of impulsive and/or future oriented decision-making associated with smoking, drug use, relapse, and treatment response. Delay discounting is the degree to which one discounts or de-values delayed or long-term outcomes. Discounting has been applied to a variety of commodities (i.e., money, cigarettes, drugs, health, etc.), magnitudes ($5, $100, $1,000, etc.), and “signs” (i.e., gains, losses). Most individuals prefer immediate rewards and prefer to delay losses, but most are also willing to wait some time for larger rewards or take an immediate loss in lieu of a larger loss later. Smokers and other substance dependent individuals consistently discount the value of commodities more steeply than former and never users. Lower rates of discounting are associated with a higher likelihood of achieving abstinence.

Converging evidence indicates that delay discounting is closely associated with relative activity in the PFC and limbic regions. Choosing delayed options with larger rewards, arguably required to maintain abstinence from tobacco or drugs, is associated with increased activity in the PFC relative to activity in limbic regions. Choosing to smoke after making a decision to quit might then present a situation where the DLPFC is insufficiently activated to exert an inhibitory influence on the choice to smoke versus other options. Neuromodulation of the DLPFC has been shown to affect the discounting of monetary gains as well as affect other types of risky decision-making.

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS), the neuromodulatory technique used in this study, has acute effects on neuronal activity that are thought to be either excitatory or inhibitory depending on the frequency of the pulses delivered although there are exceptions in the evidence. Low frequency (LF; ≤ 3Hz) is believed to inhibit cortical excitability and high frequency (HF; >3Hz) to increase cortical excitability. Very HF rTMS (~50Hz) called theta burst stimulation (TBS) administered intermittently at 5 Hz is believed to increase cortical excitability; continuous TBS (cTBS) is believed to inhibit cortical excitability.

Neuromodulation of the DLPFC affects decision-making in the expected directions. Inhibiting activity in the left DLPFC with LF rTMS increases delay discounting of monetary gains. Inhibiting activity in the right DLPFC with cTBS decreases delay discounting of monetary gains. Inhibiting activity in the right, but not the left, DLPFC increased riskier decision-making in the risky choices gambling task (RCGT). Evidence suggests that increasing activity in the left DLPFC with HF rTMS will decrease delay discounting of monetary gains and losses as well as decrease riskier decision-making in the RCGT, but this has not been tested in individuals without an addiction or in smokers, who are known to discount more steeply than non-smokers.

Increasing activity in the left DLPFC is known to reduce cigarette consumption among treatment seeking smokers, and in some instances, reduce craving to smoke. Although the mechanisms by which rTMS affects cigarette consumption and craving are unclear, it has been suggested that rTMS affects neurobiological factors by increasing the availability of dopamine in the reward system in the brain. However, given the inhibitory role of the DLPFC, the effects of stimulation of the DLPFC on delay discounting, and the role of delay discounting in smoking, we suggest that the mechanisms might also include sufficiently activating the DLPFC to enable it to exert an inhibitory influence on the choice to smoke versus other options.

In this study we examined the effects of 20Hz, 10Hz, and sham rTMS applied to the left DLPFC on the delayed discounting of monetary gains and losses and on performance in the RCGT in smokers with no intention to quit and in non-smokers. We also examined the effects of these conditions on discounting of cigarettes and cigarette consumption among the smokers. We hypothesized that increasing activity in the left DLPFC with HF rTMS would decrease delay discounting of monetary and cigarette gains and losses as well as decrease impulsive and risky decision-making in the RCGT. We expected smokers to take less time and earn fewer points on the RCGT. We expected the highest intensity of stimulation to have the greatest effects and the results to be consistent with previous research such that smokers would discount more than nonsmokers, smaller magnitudes would be discounted more than larger magnitudes (the magnitude effect), and gains would be discounted more than losses in a positive symmetrical manner (the sign effect).

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 19–55 years of age; not pregnant; English-speaking; right-handed; and had no personal or family history of epilepsy or seizures; no personal history of head injury with unconsciousness; no aneurysm, stroke, neurosurgery, psychiatric disorder that required hospitalization, tinnitus, metal implants in head, neck, or cochlea, pacemaker, migraine headaches, and medications that lower seizure threshold. Participants passed screening tests for claustrophobia and a urine test for drugs of abuse. Smokers were required to smoke at least 10 cigarettes per day, have a mean motivational score of 7 or less on a scale of 0–10 (0=lowest, 10=most ever), and have no plans to quit smoking in the next 30 days. After passing the screening interview, a high resolution MRI was taken of the head. Results of the MRI were used for further screening and for precisely locating the stimulation site. The MRI was reviewed by a staff radiologist and the study physician. If the results revealed abnormalities that precluded the safe administration of rTMS, participants were withdrawn.

Procedure

Preparation

All participants were prepared in the same manner regardless of condition. Smokers were required to smoke one cigarette immediately before beginning session procedures. Two stimulating electrodes were placed over the left frontalis muscle underneath the headband holding the Brainsight head tracker. To assess motor threshold (MT), three recording electrodes were placed over the right abductor pollicis brevis (APB) muscle of the hand. MT was defined as the minimum stimulation intensity required to elicit a motor evoked potential (MEP) of 50 μV from the APB in 3 of 6 trials. Once a participant’s MT was determined, the participant was escorted out of the room. The active or sham rTMS coil was then attached by the technician as per the counterbalancing schedule. The participant was escorted back into the room, positioned, and the target site for stimulation, 6 cm anterior to the MT location over the left DLPFC, was located and marked. The stimulating electrodes were attached to the DS3 Stimulator located outside of the participant’s field of vision and only activated during the sham condition.

Stimulation parameters

Participants underwent three counterbalanced conditions of 900 pulses of HF rTMS (20Hz, 10Hz, sham) separated by at least 48 hours [20Hz, 110% MT, 1 sec on, 20 sec off; 10Hz, 110% MT, 1 sec on, 20 sec off]. The sham was focal electrical stimulation delivered at 10Hz [1 sec on, 20 sec off] with a mean amperage of 5.5mA (SD 2.1), the most effective sham technique available at this time. Smokers were provided with two packs of cigarettes after each session to ensure that resources did not affect cigarette consumption. After completing this phase, smokers were invited to repeat each condition after 24 hours of abstinence. These results will be reported elsewhere.

Measures

Demographic and tobacco use characteristics were collected including the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND). Post-session number of cigarettes smoked per hour were assessed with a tracking form and a timeline follow-back procedure administered by telephone 6 hours and 24 hours after stimulation.

Delay Discounting

Delay discounting tasks were administered at baseline and immediately after each stimulation session. Participants were seated comfortably in front of a computer screen. The software prompted participants to make successive decisions between smaller, immediate rewards and larger, delayed rewards. All participants completed tasks for gains and losses for two hypothetical magnitudes ($100, $1,000). Smokers completed additional tasks for the cigarette equivalents of $100 and $1,000. To determine the cigarette equivalents, smokers were asked: “I want you to imagine that you have a choice between receiving some money and receiving some cigarettes. For the following statements, fill in the number of cigarettes that would make the two choices equally attractive to you. Receiving $100 right now would be just as attractive as receiving ___cigarettes. Receiving $1000 right now would be just as attractive as receiving ___ cigarettes.”

Gains and losses of $100 and $1,000 were presented as four separate tasks. For each task, a series of choices were presented for each of seven delays: 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, 5 years, and 25 years. For gains, participants were presented with choices comprised of receiving smaller amounts now or the larger constants after the delay. For losses, participants were presented with choices comprised of losing smaller amounts now or the larger constants after the delay. The first choice in a task was always half the value of the delayed gain or loss with subsequent choices adjusting the immediate option according to whether the participant previously chose the immediate (adjusted up) or delayed (adjusted down) outcome. The final value for a task was the indifference point, which is the value of the immediate outcome, expressed as a proportion, subjectively deemed equivalent to the larger, delayed outcome.

The discounting rate (k) was estimated with nonlinear regression using Mazur’s (1987) hyperbolic-decay model, vd = V/(1+kd), where V is the value of a an outcome delayed by d days and vd is the value of the immediate outcome – a proportion of V subjectively discounted at “rate” k. Distributions of k-values transformed with the natural logarithm (ln) tend to be approximately normal. Analyses were performed on ln(k). The ln(k) for these discounting tasks tend to range from −12.00 to 4.00 with the discounting rates increasing as the value of ln(k) increases.

Risky choices gambling task (RCGT)

The RCGT measures risky decision-making with little strategic planning. The RCGT was administered at baseline and after each of the three conditions. Participants were seated comfortably in front of a computer screen on which they were presented with six horizontal blocks colored either pink or blue and told that they needed to select the box that hid the prize to win points. The ratio of pink-to-blue boxes determined the probability of finding the prize and varied from trial to trial (5:1, 4:2, 3:3) along with the number of points at risk. A correct choice added points; an incorrect choice subtracted points. The greatest number of points was always associated with the least likely and most risky outcome. Total points were continuously displayed. Thirty trials were administered. Total points-earned and total time-to-complete were recorded automatically.

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to characterize participants. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to examine differences between smokers and nonsmokers in delay discounting and the RCGT at baseline and after each condition. With condition and magnitude entered as within-subjects factors, ANOVAs were also utilized to examine the effects of condition (baseline, 20Hz, 10Hz, sham), smoking status, and magnitude ($100, $1000) on delay discounting of gains and losses of money and cigarettes; to examine the effects of condition and smoking status on points-earned and time-to-complete in the RCGT; and to examine the effects of condition on cigarette consumption. To account for the repeated measures portion of the models, either an exchangeable (a.k.a., compound symmetric) or a heterogeneous exchangeable covariance structure was utilized. Error degrees of freedom were adjusted with the Kenward-Roger’s method. The a priori comparisons for discounting and RCGT included: baseline versus 20Hz, 10Hz, and sham. A priori comparisons for cigarette consumption included: sham versus 20Hz, and 10Hz. Dunnett’s method and Holm’s Step-down method were used to control the Type I error rate at 0.05 among comparisons as appropriate. All reported confidence intervals (CI) and p-values were adjusted accordingly. All analyses were conducted in SAS® V9.2 primarily using the MIXED procedure.

The analyses were conducted using two approaches: The All-In Analyses (AIA) included all participants who completed at least one condition; and the Complete Case Analyses (CCA) included only those participants who completed all conditions. Values for discounting are reported on the loge scale.

RESULTS

Participants

Participants (N=66) were 61% male with a mean age 41.3 (SD 10.4) years; they were 71% white, 26% African-American, and 3% American Indian or other; 99% non-Hispanic; and 68% un-partnered. They had a mean of 13.4 (SD 2.3) years of education; 58% were employed full- or part-time, 36% unemployed, and 6% retired, disabled, homemakers, or students. About two-thirds of participants (62%) reported household incomes less than $25,000; 39.4% had private health insurance; 59.1% had no health insurance, and 1.5% had Medicare. Smokers (n=47, 71% of N) reported a mean of 21.23 (SD 11.0) cigarettes per day, a mean FTND score of 5.3 (SD 2.0), and a mean longest period of abstinence of 87 days (range 0–1,440 days; median 30 days, mode 0 days).

For cigarette equivalents, no differences were found among the medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) of cigarettes deemed equivalent to $100 gains and to $100 losses (median = 400, IQR: 300 – 600); $1,000 gains and losses (median = 4,000, IQR: 2,000 – 5,000); and for the AIA and the CCA models.

The AIA are considered the main results because we have no reason to believe that the data supplied by those who did not complete all conditions were invalid, and the AIA and CCA models produced nearly identical patterns in the results. Nonetheless, the CCA models were less likely to reflect significant results primarily because the CCA models only included those participants who completed all three conditions. For this reason, and in the interest of being succinct, we will only present the AIA models in the results.

Smokers and nonsmokers differed in continued eligibility and compliance after enrollment. We collected baseline data on 47 smokers; 33 (70%) attended the scheduled MRI visit; 27 (57% of enrolled) passed the MRI screen; and just 16 (34% of enrolled) completed all three conditions. In contrast, we collected baseline data on 19 nonsmokers; 16 (84% of enrolled) attended their MRI visit; 16 (100% passed the MRI screen and completed all three conditions. Typical of the smoking population in the US, smokers were more likely to be male (χ2=6.31, df=1, p=.01), have lower incomes (χ2=11.66, df=5, p=.04), lower educational levels (χ2=22.70, df=3, p=.01), and were less likely to have private healthcare insurance (χ2=17.53, df=2, p<.0001).

Delay discounting

Differences between smokers and nonsmokers

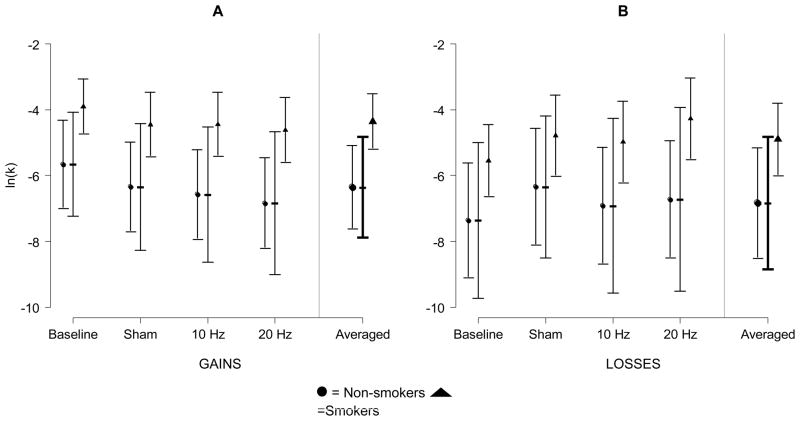

Consistent with previous research, smokers discounted monetary gains and losses more than nonsmokers at baseline and after every condition. See Figure 1. For monetary losses, the differences were not significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Figure 1.

Mean discounting of monetary gains (A; n=66 participants, 325 observations) and losses (B; n=66 participants, 322 observations) plotted by condition and smoking status (nonsmokers = circles, smokers=triangles). The y-axis is the discounting rate expressed as the natural logarithm of k. Dotted error bars are 95% CIs among conditions. Solid error bars are 95% CIs for the differences between nonsmokers and smokers among conditions. A significant difference, at the .05 level, between nonsmokers and smokers is present when the solid bar does not cover both the circle and the triangle (corrected for 4 multiple comparisons with Holm’s Step-down method).

Monetary gains

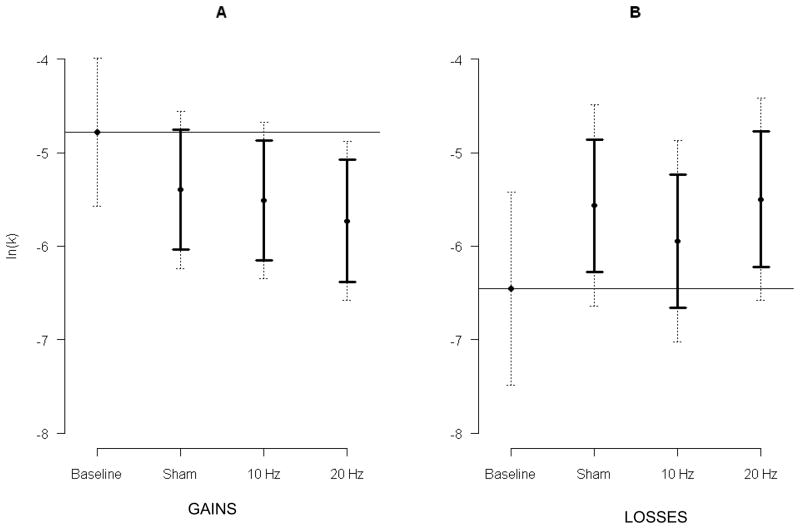

The model for gains included 325 observations from 66 participants. Delay discounting differed by condition (F[3, 250] = 4.46, p=.005), smoking status (F[1, 62.9] = 6.88, p=.011), and magnitude (F[1, 245] = 43.26, p<.001). See Figure 2 and Table 1. Consistent with our hypothesis, stimulation decreased delay discounting compared to baseline and the highest intensity of stimulation (20Hz) demonstrated the lowest discounting rate. Twenty Hz decreased discounting 0.949 (loge scale; CI: 0.293, 1.605; t[255] = 3.42, padj=.002); 10Hz decreased discounting 0.729 (CI: 0.088, 1.371; t[255] = 2.69, padj=.021); and sham decreased discounting 0.616 (CI: −0.024, 1.257; t[254] = 2.28, padj=0.063). Smokers discounted more than nonsmokers (mean difference =1.999, CI: 0.476, 3.52). The $100 magnitude was discounted more than the $1,000 magnitude (mean difference = 1.235, CI: 0.865, 1.605. No interactions between condition and smoking status (F[3, 250] = 0.29, p=.829) and between condition and magnitude (F[3, 244] = 0.77, p=.510) were found.

Figure 2.

Mean discounting of monetary gains (A; n=66 participants, 325 observations) and losses (B; n=66 participants, 322 observations) plotted by condition. The y-axis is the discounting rate expressed as the natural logarithm of k. The horizontal line is the baseline mean. Dotted error bars are the 95% CIs among conditions. Solid error bars are 95% CIs for the a priori comparisons between sham, 10Hz, and 20Hz conditions and the baseline mean. A significant difference, at the .05 level, is present when the solid bar does not cross the mean baseline value (corrected for 3 multiple comparisons with Dunnett’s method).

Table 1.

Pattern of results from delay discounting and risky choices gambling tasks

| Delay discounting (decrease = preference for larger later gains or smaller sooner losses) | Monetary gains | Condition** | 20Hz < Baseline** |

| 10Hz < Baseline* | |||

| Sham < Baseline | |||

| Smoking status** | Smokers > nonsmokers | ||

| Magnitude*** | $100 > $1,000 | ||

|

| |||

| Monetary losses | Condition** | 20Hz > Baseline** | |

| 10Hz > Baseline | |||

|

|

Sham > Baseline** | ||

| Smoking status± | Smokers > nonsmokers | ||

| Magnitude*** | $100 > $1,000 | ||

|

| |||

| Cigarette gains | Condition± | 20Hz < Baseline | |

| 10Hz < Baseline | |||

| Sham < Baseline* | |||

| Magnitude | nd | ||

|

| |||

| Cigarette losses | Condition | nd | |

| Magnitude | nd | ||

|

| |||

| Risky choices gambling task | Points-earned | Condition** | 20Hz > Baseline |

| 10Hz > Baseline* | |||

| Sham > Baseline** | |||

|

| |||

| Smoking status** | Smokers < nonsmokers | ||

|

|

|

||

| Time-to-complete | Condition*** | 20Hz < Baseline** | |

| 10Hz < Baseline** | |||

| Sham < Baseline** | |||

|

| |||

| Smoking status | Smokers > nonsmokers | ||

p=.06;

p=.05;

p=.01;

p=.001;

nd=no difference

Monetary losses

The model for losses included 322 observations from 66 participants. Delay discounting differed by condition (F[3, 246] = 4.30, p<.01), approached a significant difference by smoking status (F[1, 64.2] = 3.69, p=.06), and differed by magnitude (F[1, 242] = 13.25, p<.001). See Figure 2 and Table 1. Contrary to our hypothesis, stimulation increased delay discounting. The highest intensity of stimulation (20Hz) demonstrated the highest discounting rate. Twenty Hz increased discounting 0.957 (CI: 0.235, 1.679; t[249] = 3.14, p<.01), 10Hz increased discounting 0.506 (CI: −0.205, 1.217, t[250] = 1.69, p=.23), and sham increased discounting 0.890 (CI: 0.182, 1.597; t[249] = 2.98, p<.01). Smokers discounted 1.935 more than nonsmokers (CI: −0.076, 3.947, t[64.2]=1.92, p=.06). The $100 magnitude was discounted more than $1,000 (mean increase = 0.754, CI: 0.346, 1.162; t[242] = 3.64, p<.001). No interactions between condition and smoking status (F[3, 246] = 0.72, p=.54) and between condition and magnitude (F[3, 242] = 0.24, p=.87) were found.

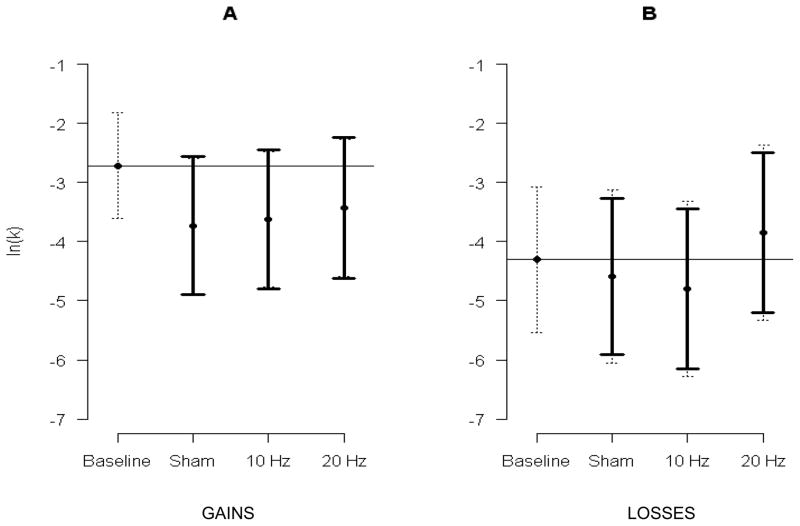

Cigarette gains

The model for cigarette gains included 201 observations from 47 smokers. Delay discounting approached a significant difference by condition (F[3, 159] = 2.55, p=.06). See Figure 3 and Table 1. No difference was found for magnitude (mean of $100 cigarettes = −3.369 versus $1,000 cigarettes = −3.530; t[149]=0.47, p=.64). Consistent with our hypotheses, stimulation decreased delay discounting, but inconsistent with our hypotheses, the highest intensity of stimulation (20Hz) did not demonstrate the lowest discounting rate. Twenty Hz decreased discounting 0.855 (CI: −0.340, 2.049; t[166]=1.71, p=.22); 10 Hz decreased discounting 1.047 (CI: −0.130, 2.224; t[167]=2.12, p=.09); sham decreased discounting 1.200 (CI: 0.030, 2.371; t[166]=2.45, p=.04). No interaction between condition and magnitude was found (F[3, 148] = 0.69, p=.56).

Figure 3.

Mean discounting of cigarette gains (A; n=47 smokers, 205 observations) and losses (B; n=46 smokers, 201 observations) plotted by condition. The y-axis is the discounting rate expressed as the natural logarithm of k. The horizontal line is baseline mean. Dotted error bars are the 95% CIs among conditions. Solid error bars are 95% CIs for the a priori comparisons between sham, 10Hz, and 20Hz conditions and the baseline mean. A significant difference, at the .05 level, is present when the solid bar does not cross the mean baseline value (corrected for 3 multiple comparisons with Dunnett’s method).

Cigarette losses

The model for cigarette losses included 198 observations from 47 smokers. Delay discounting of cigarette losses did not differ by condition (F[3, 144] = 0.86, p=.46) or magnitude (F[1, 144]=0.06, p=.81). See Figure 3 and Table 1. No interaction between condition and magnitude was found (F[3, 144] = 0.64, p=.59).

Risky Choices Gambling Task

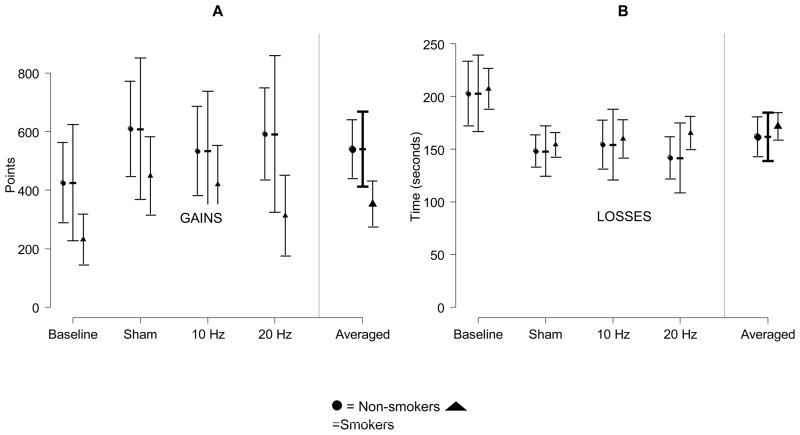

Differences between smokers and nonsmokers

Consistent with our hypotheses and previous research, smokers made riskier decisions and earned fewer points on the RCGT. This was true at baseline and after each condition, but the difference was only significant at baseline and after the 20Hz conditions. No significant differences were found between smokers and nonsmokers in time-to-complete the RCGT any point. See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

In the risky choices gambling task, mean points earned (A; n=66 participants, 325 observations) and time-to-complete (B; n=66 participants, 322 observations) plotted by condition and smoking status (nonsmokers=circles, smokers=triangles). Dotted error bars are 95% CIs among conditions. Solid error bars are 95% CIs for differences between nonsmokers and smokers among conditions. A significant difference, at the .05 level, between nonsmokers and smokers is present when the solid bar does not cover both the circle and the triangle (corrected for 4 multiple comparisons with Holm’s Step-down method).

Points-earned

The model for points-earned on the RCGT included 164 observations from 66 participants. Number of points-earned differed by condition (F[3,108]=4.34, p<.01) and smoking status (F[1,48.4]=8.58, p<.01). Consistent with our hypotheses, stimulation increased the number of points-earned from baseline; however, inconsistent with our hypotheses, the greatest intensity of stimulation demonstrated the smallest increase in the number of points and the sham condition demonstrated the greatest increase in the number of points. After the 20Hz condition, the points-earned increased 124.2 points (CI: −19.7, 268.1; t[114]=2.07, p=.11); 10 Hz, points-earned increased 148.5 points (CI: 7.8, 289.2; t[113]=2.53, p=.04); and sham, points-earned increased 200.7 points (CI: 55.9, 345.5; t[114]= 3.32, p<.01). Nonsmokers earned more points than smokers (mean difference 187 points; CI: 58.7, 315.4; t[48.4]=2.93, p<.01). No interaction between condition and smoking status was found (F[3,108]=0.57, p=.64).

Time-to-complete

The model for time-to-complete the RCGT included 164 observations from 66 participants. Time-to-complete differed by condition (F[3,74.4]=19.82, p<.001), but not smoking status (F[1,62.1]=0.73, p<.40). Participants completed the task more quickly after stimulation than at baseline; however, similar to points-earned, participants completed the RCGT the most quickly after the sham condition. After the 20 Hz condition, the time-to-complete decreased 51 seconds (CI: 34, 69; t[90.9]=6.95, p<.001); 10 Hz, decreased 48 seconds (CI: 38, 65; t[91.4]=6.40, p<.001); and sham, decreased 54 seconds (CI: 37, 71; t[80.1]=7.31, p<.001). No interaction between condition and smoking status was found (F[3,7,4.4]=1.19, p=.32).

Cigarette consumption

The model for cigarette consumption included 51 observations from 47 participants. Self-reported cigarette consumption 6 hours and 24 hours after stimulation did not differ by condition (6 hours, F[2,27]=0.01, p=.99; 24 hours, F[2,27.8] =0.79, p=.46).

DISCUSSION

The findings in this study provide new insights into the cognitive processes involved with impulsive and/or future-oriented decision-making and cigarette consumption. HF rTMS of the left DLPFC decreased delay discounting of monetary gains in smokers and nonsmokers, as predicted. These findings are consistent with increasing the inhibitory functions of the DLPFC and suggest that brain stimulation might assist substance dependent individuals make less impulsive, more future-oriented decisions. Translation of these findings are potentially far-reaching and include using brain stimulation as a component in the treatment of smoking and other addictive disorders, overeating, overspending, and other dysfunctional health behaviors.

As expected, stimulation did not change the magnitude effect and smokers consistently discounting more than nonsmokers, however, contrary to our hypothesis, HF rTMS of the left DLPFC increased discounting of losses while it simultaneously decreased the discounting of gains, altering the expected symmetry of the sign effect in delay discounting, the pattern whereby gains and losses are discounted in a positive, symmetrical manner. Stimulation instead produced a reflection effect, a common, natural pattern in risk estimations described in Prospect Theory whereby risk aversion in the positive domain is accompanied by risk seeking in the negative domain, or the preference for negative prospects mirrors the preference for positive prospects. This pattern in the results was similar among commodities and among smokers and nonsmokers and suggests that there are distinct, qualitative differences in the manner in which gains and losses are discounted and that the DLPFC plays a significant albeit different role for gains and losses. These findings have implications for understanding decision-making about delayed losses such as in the use of credit, but also extend to understanding substance use decision-making among substance users. The reflection effect also might limit the translation of the findings relative to decreasing discounting of gains.

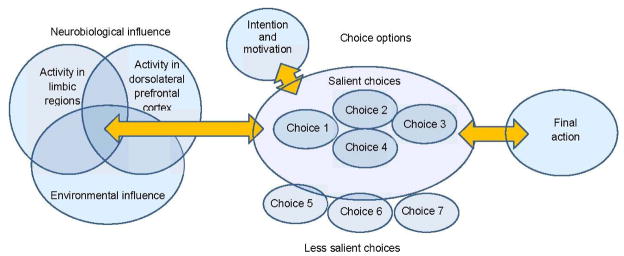

Our findings indicate that HF rTMS has no effect on cigarette consumption among smokers with no intention to quit and contrast with findings from studies where smokers were motivated to quit. If the mechanism whereby rTMS affects cigarette consumption is by increasing the availability of dopamine in the reward system, we would expect to see a reduction in consumption after stimulation regardless of intention to quit, similar to the effects of cessation medications on unmotivated smokers. Our results do not even suggest a trend in this direction. Our findings suggest that the mechanism whereby rTMS reduces cigarette consumption interacts with intention or motivation to quit and is unlikely to be solely through increasing the availability dopamine in the reward system. Nonetheless, these findings are consistent with conceptual frameworks of decision-making (see Figure 5) whereby the DLPFC exerts an inhibitory influence and perceived choice options are important in the final action. We suggest that intention to quit might affect cigarette consumption by increasing the number, salience, or value of options alternative to smoking and that HF rTMS was effective in helping motivated smokers reduce consumption by enabling smokers to more effectively inhibit the choice to smoke in the presence of choices alternative to smoking. Perhaps rTMS was ineffective in helping unmotivated smokers reduce consumption because choices alternative to smoking were not salient or valued or were few in number (i.e., they had not given any thought of what else to do). We suggest that HF rTMS decreased delay discounting in smokers, even though it did not decrease cigarette consumption, because the delay discounting task has clearly defined choice options that include a salient larger later reward. Using this framework for decision-making, HF rTMS can enable individuals to make less impulsive, more future-oriented decisions, but it is only effective when individuals perceive there to be clear alternative choices. This suggests that HF rTMS might be most effective when paired with cognitive-behavioral therapy that addresses motivation to quit and explores alternative behavioral choices.

Figure 5.

The process of decision-making is influenced by neurobiological, environmental, and cognitive factors such as intention and/or motivation to quit and the perceived selection and organization of choices. Neuromodulation can influence decision-making by affecting the inhibitory influences of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex thereby altering individual’s ability to select smaller sooner versus larger later rewards. This model is adapted from the work of Levasseur-Moreau et al. 2012 and Fecteau et al 2010.

Findings from the RCGT indicate that smokers take about the same amount of time as nonsmokers to make less effective decisions (i.e., earn fewer points in the RCGT) and do not rule out practice effects in the RCGT and/or a placebo effect in the rTMS for this task because 20Hz, 10Hz, and sham all were greater than baseline. Others have found placebo responses from rTMS on certain measures. Nonetheless, we used the most effective sham technique available at this time for comparison purposes and a placebo effect does not explain the lesser effect of the 20Hz condition for this task. Alternatively, perhaps active HF rTMS actually depressed the increases derived from practice and/or placebo effects. Although this explanation fully explains the results, it adds to the exceptions in the evidence that HF rTMS has a stimulatory effect.

In the context of previous research, these findings indicate that HF rTMS of the left DLPFC modulates delayed discounting of gains and losses and suggests that the effects of stimulation interact with smokers’ intentions to quit in order to affect cigarette consumption. This suggests that like all medications for tobacco dependence and substance dependence, HF rTMS is likely to be most effective when paired with evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapy that addresses motivation to quit and explores alternative behavioral choices. More research is clearly needed to understand the implications of these findings within models of addictive decision-making and particularly with regard to the reflection effect. Future research should consider repeated sessions of rTMS and comparing motivated and unmotivated smokers in the same study.

Strengths and limitations

The causal relations deduced from this study are bolstered by the counterbalanced design, multiple intensity conditions, the collection of baseline comparison data, and the use of a previously validated sham technique. The comparisons between smokers and nonsmokers in this study are limited by significant differences in continued eligibility and compliance after enrollment as well as demographic factors. Nonetheless, these differences are reflective of common differences among smokers and nonsmokers and contribute to the generalizability of the results.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by awards from the National Center for Research Resources (P20 RR20146, 1UL1RR029884), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD055677, HD055269), National Institute of Deafness and Communication Disorders (P20 GM103425 and DC011824).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Sheffer has received research funding from Pfizer, Inc. Dr. Bickel is a principal in HealthSIm LLC. Drs. Mennemeier, Dornhoffer, Landes, and Kimbrell, and Ms. Brackman, and Brown reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Department of Health and Human Services. How tobacco smoke causes disease: The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie G. Specious reward: A behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychological Bulliten. 1975;82:483–496. doi: 10.1037/h0076860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie G, Haslam N. Hyperbolic discounting. In: Loewenstein G, Elster J, editors. Choice Over Time. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1992. pp. 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Amiaz R, Levy D, Vainiger D, Grunhaus L, Zangen A. Repeated high-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex reduces cigarette craving and consumption. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Addiction. 2009;104(4):653–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arana AB, Borckardt JJ, Ricci R, Anderson B, Li X, Linder KJ, George MS. Focal electrical stimulation as a sham control for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: Does it truly mimic the cutaneous sensation and pain of active prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation? [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.] Brain Stimul. 2008;1(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(3):382–392. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear MF. Homosynaptic long-term depression: a mechanism for memory? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(17):9457–9458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: A neurocognitive perspective. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(11):1458–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, Gatchalian KM. Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: emerging evidence. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Pharmacol Ther. 2012;134(3):287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Madden GJ. A comparison of measures of relative reinforcing efficacy and behavioral economics: cigarettes and money in smokers. [Clinical Trial Comparative Study Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10(6–7):627–637. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199911000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Miller ML, Yi R, Kowal BP, Lindquist DM, Pitcock JA. Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(Suppl 1):S85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.016. doi: S0376-8716(06)00360-7 [pii]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pitcock JA, Yi R, Angtuaco EJ. Congruence of BOLD response across intertemporal choice conditions: fictive and real money gains and losses. [Comparative StudyResearch Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] J Neurosci. 2009;29(27):8839–8846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5319-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R. Temporal discounting as a measure of executive function: insights from the competing neuro-behavioral decision system hypothesis of addiction. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res. 2008;20:289–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Kowal BP, Gatchalian KM. Cigarette smokers discount past and future rewards symmetrically and more than controls: is discounting a measure of impulsivity? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96(3):256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.009. doi: S0376-8716(08)00103-8 [pii]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borckardt JJ, Walker J, Branham RK, Rydin-Gray S, Hunter C, Beeson H, George MS. Development and evaluation of a portable sham transcranial magnetic stimulation system. [Evaluation Studies] Brain Stimul. 2008;1(1):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Classen J, Gerloff C, Celnik P, Wassermann EM, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Depression of motor cortex excitability by low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology. 1997;48(5):1398–1403. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SS, Ko JH, Pellecchia G, Van Eimeren T, Cilia R, Strafella AP. Continuous theta burst stimulation of right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex induces changes in impulsivity level. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Brain Stimul. 2010;3(3):170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Pilato F, Saturno E, Oliviero A, Dileone M, Mazzone P, Rothwell JC. Theta-burst repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation suppresses specific excitatory circuits in the human motor cortex. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] J Physiol. 2005;565(Pt 3):945–950. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhammer P, Johann M, Kharraz A, Binder H, Pittrow D, Wodarz N, Hajak G. High-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation decreases cigarette smoking. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(8):951–953. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Paulus MP. Neurobiology of decision making: a selective review from a neurocognitive and clinical perspective. [Review] Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(8):597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estle SJ, Green L, Myerson J, Holt DD. Differential effects of amount on temporal and probability discounting of gains and losses. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Mem Cognit. 2006;34(4):914–928. doi: 10.3758/bf03193437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JS. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Review] Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:255–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J Behav Med. 1989;12(2):159–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00846549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecteau S, Fregni F, Boggio PS, Camprodon JA, Pascual-Leone A. Neuromodulation of decision-making in the addictive brain. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(11):1766–1786. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecteau S, Knoch D, Fregni F, Sultani N, Boggio P, Pascual-Leone A. Diminishing risk-taking behavior by modulating activity in the prefrontal cortex: a direct current stimulation study. J Neurosci. 2007;27(46):12500–12505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3283-07.2007. doi: 27/46/12500 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3283-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecteau S, Pascual-Leone A, Zald DH, Liguori P, Theoret H, Boggio PS, Fregni F. Activation of prefrontal cortex by transcranial direct current stimulation reduces appetite for risk during ambiguous decision making. J Neurosci. 2007;27(23):6212–6218. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0314-07.2007. doi: 27/23/6212 [pii]10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0314-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figner B, Knoch D, Johnson EJ, Krosch AR, Lisanby SH, Fehr E, Weber EU. Lateral prefrontal cortex and self-control in intertemporal choice. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.] Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(5):538–539. doi: 10.1038/nn.2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, Wewers ME. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service; 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PB, Fountain S, Daskalakis ZJ. A comprehensive review of the effects of rTMS on motor cortical excitability and inhibition. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S. Review] Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(12):2584–2596. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MS, Nahas Z, Kozel FA, Li X, Denslow S, Yamanaka K, Bohning DE. Mechanisms and state of the art of transcranial magnetic stimulation. J ECT. 2002;18(4):170–181. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200212000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GM. Addiction: A disorder of choice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WF, Schwartz DL, Huckans MS, McFarland BH, Meiri G, Stevens AA, Mitchell SH. Cortical activation during delay discounting in abstinent methamphetamine dependent individuals. [Clinical Trial Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.] Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;201(2):183–193. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1261-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. [Clinical Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Neuron. 2005;45(2):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Dube SR, Malarcher AM, Shaw L, Engstrom MC. Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults - national ambulatory medical care survey and national health interview survey, United States, 2005–2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(2):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johann M, Wiegand R, Kharraz A, Bobbe G, Sommer G, Hajak G, Eichhammer P. Repetitiv Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Nicotine Dependence. Psychiatr Prax. 2003;30(Suppl 2):129–131. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. J Exp Anal Behav. 2002;77(2):129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theroy: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47(2):263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lee D. Prefrontal cortex and impulsive decision making. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review] Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(12):1140–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN. Bidding on the future: Evidence against normative discounting of delayed rewards. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1997;126:54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Knoch D, Fehr E. Resisting the power of temptations: the right prefrontal cortex and self-control. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1104:123–134. doi: 10.1196/annals.1390.004. doi: annals.1390.004 [pii] 10.1196/annals.1390.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoch D, Gianotti LR, Pascual-Leone A, Treyer V, Regard M, Hohmann M, Brugger P. Disruption of right prefrontal cortex by low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation induces risk-taking behavior. J Neurosci. 2006;26(24):6469–6472. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0804-06.2006. doi: 26/24/6469 [pii]10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0804-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. The neurobiology of addiction: a neuroadaptational view relevant for diagnosis. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review] Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl 1):23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krain AL, Wilson AM, Arbuckle R, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Distinct neural mechanisms of risk and ambiguity: a meta-analysis of decision-making. [Meta-Analysis Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Neuroimage. 2006;32(1):477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Reynolds B, Duhig AM, Smith A, Liss T, McFetridge A, Potenza MN. Behavioral impulsivity predicts treatment outcome in a smoking cessation program for adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.006. doi: S0376-8716(06)00336-X [pii] 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur-Moreau J, Fecteau S. Translational application of neuromodulation of decision-making. Brain Stimul. 2012;5(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue AW. Research on self-control: An integrating framework. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1988;11:665–709. [Google Scholar]

- Mackillop J, Amlung MT, Wier LM, David SP, Ray LA, Bickel WK, Sweet LH. The neuroeconomics of nicotine dependence: A preliminary functional magnetic resonance imaging study of delay discounting of monetary and cigarette rewards in smokers. Psychiatry Res. 2012;202(1):20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Kahler CW. Delayed reward discounting predicts treatment response for heavy drinkers receiving smoking cessation treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(3):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.020. doi: S0376-8716(09)00174-4 [pii]10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation--a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285(5435):1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. doi: 7846 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansur CG, Myczkowki ML, de Barros Cabral S, do Sartorelli MC, Bellini BB, Dias AM, Marcolin MA. Placebo effect after prefrontal magnetic stimulation in the treatment of resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(10):1389–1397. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Mazur JE, Commons ML, Nevin JA, Rachlin H, editors. Qantitative Analysis of Behavior. Vol. 5. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Laibson DI, Loewenstein G, Cohen JD. Separate neural systems value immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Science. 2004;306(5695):503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.1100907. doi: 306/5695/503 [pii] 10.1126/science.1100907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennemeier M, Triggs W, Chelette K, Woods A, Kimbrell T, Dornhoffer J. Sham Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Using Electrical Stimulation of the Scalp. Brain Stimulat. 2009;2(3):168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146(4):455–464. doi: 10.1007/pl00005491. doi: 91460455.213 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Madden GJ, Bickel WK. Discounting of delayed health gains and losses by current, never- and ex-smokers of cigarettes. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(3):295–303. doi: 10.1080/14622200210141257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A, Tormos JM, Keenan J, Tarazona F, Canete C, Catala MD. Study and modulation of human cortical excitability with transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;15(4):333–343. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199807000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogarell O, Koch W, Popperl G, Tatsch K, Jakob F, Zwanzger P, Padberg F. Striatal dopamine release after prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in major depression: preliminary results of a dynamic [123I] IBZM SPECT study. [Clinical Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(4):307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B. Do high rates of cigarette consumption increase delay discounting? A cross-sectional comparison of adolescent smokers and young-adult smokers and nonsmokers. Behav Processes. 2004;67(3):545–549. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.08.006. doi: S0376-6357(04)00173-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.beproc.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffer C, Mackillop J, McGeary J, Landes R, Carter L, Yi R, Bickel W. Delay discounting, locus of control, and cognitive impulsiveness independently predict tobacco dependence treatment outcomes in a highly dependent, lower socioeconomic group of smokers. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Am J Addict. 2012;21(3):221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Siobell MC. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Ryan SR, Fu H, Landes RD, Jones BA, Bickel WK, Budney AJ. Delay discounting predicts adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20(3):205–212. doi: 10.1037/a0026543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton PK, Sejnowski TJ. Associative long-term depression in the hippocampus induced by hebbian covariance. Nature. 1989;339(6221):215–218. doi: 10.1038/339215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead LF, Lancaster T. Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use. [Meta-Analysis Review] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD005231. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005231.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strafella AP, Paus T, Barrett J, Dagher A. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human prefrontal cortex induces dopamine release in the caudate nucleus. J Neurosci. 2001;21(15):RC157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-j0003.2001. 20015457 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Li TK. Drug addiction: the neurobiology of behaviour gone awry. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(12):963–970. doi: 10.1038/nrn1539. doi: nrn1539 [pii] 10.1038/nrn1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing VC, Bacher I, Wu BS, Daskalakis ZJ, George TP. High frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces tobacco craving in schizophrenia. [Letter Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Schizophr Res. 2012;139(1–3):264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing VC, Moss TG, Rabin RA, George TP. Effects of cigarette smoking status on delay discounting in schizophrenia and healthy controls. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Sommer M, Tergau F, Paulus W. Lasting influence of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on intracortical excitability in human subjects. Neurosci Lett. 2000;287(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01132-0. doi: S0304-3940(00)01132-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Sugarbaker RJ, Thomas CS, Badger GJ. Delay discounting predicts postpartum relapse to cigarette smoking among pregnant women. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(2):176–186. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.186. doi: 2007-05127-006 [pii] 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]