Summary

People plan to act in the future when an appropriate event occurs, a capacity known as event-based prospective memory [1]. Prospective memory involves forming a representation of a planned future action, subsequently inactivating the representation, and ultimately reactivating it at an appropriate point in the future. Recent studies suggest that monkeys, chimpanzees, and rats display elements of prospective memory [2–5], but it is uncertain if the full sequence (activation-inactivation-reactivation) that occurs in humans also occurs in nonhumans [6–8]. Here we asked if rats exhibit event-based prospective memory. Rats completed an ongoing temporal-discrimination task while waiting for a large meal. To promote the use of event-based prospective memory, an event (tone-pulses) provided information that the meal could be obtained soon. Event-based prospective memory was suggested by the dramatic decline in ongoing-task performance after the event, with excellent performance at other times. To document that the event initiated memory activation, the event occurred at novel times. Finally, multiple, repeated presentations of the event on the same day demonstrate that rats inactivate and reactivate the memory representation in an on-demand, event-based fashion. Development of an animal model of prospective memory may be valuable to probe the biological underpinnings of memory disorders [7, 9].

Results and Discussion

Successful prospective memory (“remembering to remember”) requires retrieval of a previously inactivated memory representation [1]. An everyday example of prospective memory is when you need to remember to take your medication after eating dinner. In this example, you may form a plan to take the medication, but it is unlikely that you rehearse this plan throughout the day. Instead, you may use a prospective-memory strategy (e.g., your meal might prompt retrieval of the previously formed plan to take medication). In laboratory studies, prospective memory produces a selective deficit in performance when anticipation of a future event occurs due to limited attentional resources being divided between the two tasks [10]; no disruption occurs when the memory representation is in an inactive state. For example, a decline in one’s work product may occur when an important future event looms (e.g., picking up one’s children before daycare closes). Importantly, a selective deficit in performance may be used to document prospective memory in animals as an index of memory activation [5]. To develop a model of event-based prospective memory, three features were included: (1) a meal was available at a distant point in the future; (2) an event was used to signal that a meal could be obtained soon; and (3) an ongoing task was used to measure the prospective-memory induced decline in performance.

Experiment 1

To provide an ongoing activity, rats were trained in a time-discrimination task [11]. In time-discrimination trials, a 2- or 8-s gap between two brief white-noise pulses was presented, and a small reward pellet was delivered if the rat pressed the correct lever to classify the signal as short or long (e.g., left/right lever presses were correct after short/long gaps, respectively); on other trials, rats classified intermediate gaps, but choices were not rewarded. To provide a planned future action, rats gained access to a large meal consisting of 8 g of food. The meal was available after 90-min of time-discrimination trials, and when the meal became available, each pellet of food was earned by breaking a photobeam located in the food trough. To promote memory activation when an event occurs [12, 13], an event (brief tone pulses) was presented intermittently 10 min before the meal; 10 min was used to provide a brief window during which a decline in ongoing-task performance could be evaluated. The tone pulses were presented in the intertrial interval between successive discrimination trials to equate these trials with other timepoints when the event was absent. A rat with prospective memory is expected to show a deleterious effect on ongoing performance in trials after the event but not prior to the event. A rat without prospective memory is expected to show equivalent performance at these timepoints.

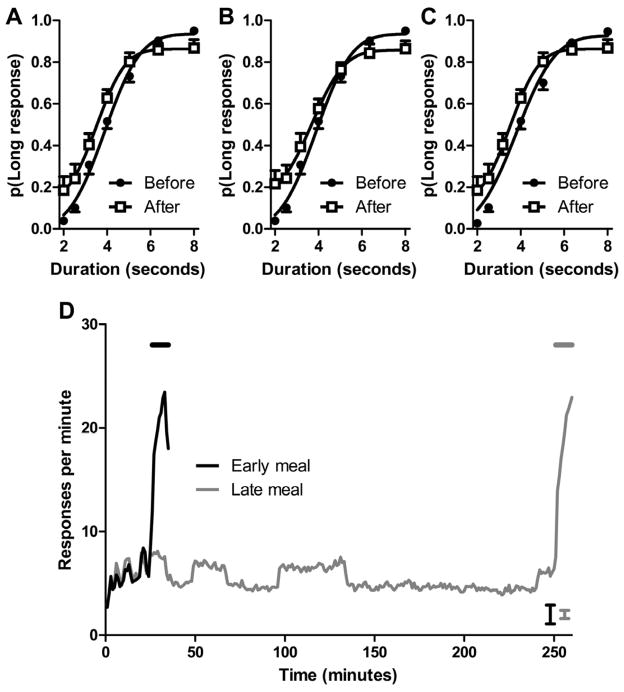

Performance in the ongoing task was disrupted by the recent presentation of the event relative to an earlier timepoint when the event had not occurred (Figure 1A), as indicated by the compressed range in the psychophysical function. Importantly, the difference between performance before and after the event depended on the gap duration (significant interaction, F(6,66)=223, p<0.05), consistent with a deleterious effect associated with activation of a prospective memory. Moreover, when cumulative-normal distributions were fit to psychophysical functions from individual rats [14], the range between the lower and upper asymptotes was significantly smaller after the event (t(11)=−4.1, p<0.01); in this and subsequent analyses, other parameters (mean and standard deviation) from the curve fitting did not differ significantly. The same conclusion about selective disruption of performance was reached when the range between endpoints (performance on 2- and 8-s gaps) was directly compared in Figure 1A (t(11)= −4.7, p<0.0001). The rats inspected the food trough increasingly during the event (Figure 1B), as indicated by more trough responses during the event compared to the preceding 10 min (F(1,11)=26.3, p<0.001) and a steeper increase during the event (F(9,99)=30.9, p<0.001). However, the rats also timed the arrival of the event and/or the meal (F(9,99)=25.6, p<0.001). Thus, although the rats used the event, they also appeared to use time.

Figure 1.

A disruption in performance is shown by a compressed range in the psychophysical function after the event provided information that the meal could be obtained soon

(A) Anticipation of a meal reduced performance in the ongoing gap-duration task after the event relative to excellent performance at an earlier timepoint. Smooth curves are the best fitting functions to the mean data shown in the figure. Data are means with 1 SEM. (B) Rats anticipated the arrival of the meal, as shown by the increase in food-trough responses before the meal and the increase that occurs when the event provided information that the meal could be obtained soon. The horizontal line indicates when the event was presented during the last 10-min before the meal. The meal could be obtained beginning at 90 min by interrupting a photobeam in the food trough. The error bar is 1 SEM averaged across 90 min.

Experiment 2

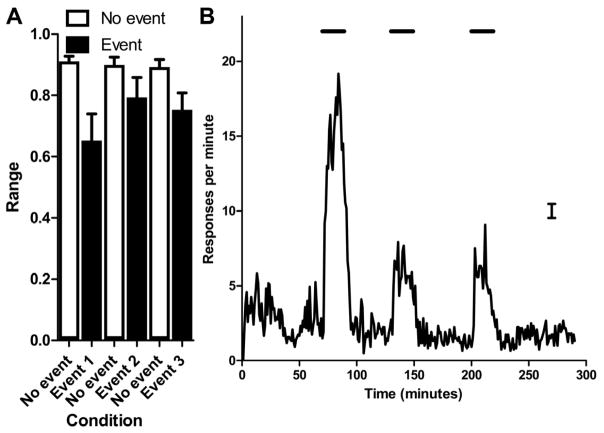

To promote the use of event rather than time in Experiment 2, the meal occurred after a variable amount of time but was preceded by the event in each case. Hence, the event, rather than time, was the most valid cue to predict the meal. The delay to the meal (35 or 260 min) was randomly determined across days, and the event occurred in the intertrial intervals between successive trials in the last 10 min before either meal; in all other respects the procedure was the same as in Experiment 1. Thus, only one meal occurred per day (at one of two times), and the event provided information that the meal could be obtained soon. Performance in the ongoing task was severely disrupted after the event, relative to an earlier timepoint when the event had not occurred, for both early and late meals (Figures 2A and 2B, respectively); the difference between performance before and after the event depended on the gap duration (significant interactions: Figure 2A, F(6,66)=6.8, p<0.001; Figure 2B, F(6,66)=8.3, p<0.001). The impairment was also documented by a reduced range between upper and lower asymptotes (Figure 2A, t(11)= −2.9, p<0.05; Figure 2B, t(11)= −3.6, p<0.01). The same conclusion about selective disruption of performance was reached when the range between endpoints (2- and 8-s gaps) was directly compared in Figure 2A (t(11)= −4.0, p<0.001) and 2B (t(11)= −4.7, p<0.001). When the analysis was restricted to the very first trial after the first presentation of the event, the same conclusion about selective disruption of performance was reached (t(11)= −2.4, p<0.05; to minimize the possibility that the data were influenced by competitive timing of 10-min intervals, we used the 5 shortest delays between a single, initial tone event and the 2- or 8-s gap from early and late meals); thus, an early, initial presentation of the event was sufficient to produce impairment (i.e., less than 5 s after the event).

Figure 2.

Performance in the ongoing task was severely disrupted after the event, relative to excellent performance at an earlier timepoint when the event had not occurred, for both early and late meals

(A–C) Anticipation of early (A) and late (B) meals severely disrupted performance in the ongoing task after the event, relative to excellent performance at an earlier timepoint. (C) When event and time were dissociated (using data from 25–34 min, with and without the event), performance was severely disrupted by the event. (A–C) Smooth curves are the best fitting functions to the mean data shown in the figure. Data are means with 1 SEM. (D) Rats anticipated the arrival of the meal, as shown by the increase in food-trough responses when the event provided information that the meal could be obtained soon; the meal could be obtained early or late (beginning at 35 or 260 min, respectively), which was randomly determined on each day. Horizontal lines indicate the last 10-min before the meal when the event was presented. The error bar is 1 SEM averaged across 35 and 260 min for each curve.

To examine the role of the event (in conditions that preclude the use of time as a cue to predict meal availability), Figure 2C shows that performance after the event was disrupted relative to an equivalent timepoint when the event had not yet occurred; this dissociation of event- and time-based cues came from 25–34 min, when the event occurred on early meal days (i.e., meal at 35 min), but the event had not yet occurred on days with late meals at 260 min. This impairment was documented by a significant interaction (F(6,66)=5.7, p<0.001), reduced range between upper and lower asymptotes (t(11)= −2.6, p<0.05), and reduced range between 2- and 8-s endpoints (t(11)= −3.8, P<0.01). This impairment in ongoing task performance can only be attributed to the event because time was held constant in Figure 2C. The rats also inspected the food trough primarily during the event (Figure 2D), as indicated by more trough responses during the event compared to the preceding 10 min (early meal: F(1,11)=14.4, p<0.01; late meal: F(1,11)=9.3, p<0.05) and a steeper increase during the event (early meal: F(9,99)=8.5, p<0.001; late meal: F(9,99)=14.2, p<0.001).

Probe with 1 event

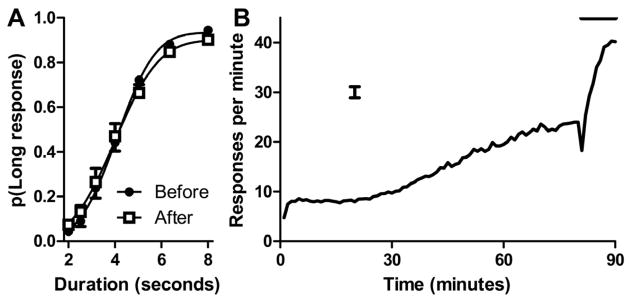

Because time and event are confounded, the impairment in the ongoing task could be due to time- or event-based prospective memory. To test the hypothesis that the event specifically caused the deleterious effect on performance (shown in Figures 2A–2C), we put time and event cues in conflict by presenting the event at a novel time. Unlike earlier experience, in which the event always occurred near the first half hour or after more than four hours, we presented the event at 151–190 min and omitted the meal. Now, when the event occurred at a novel time, performance in the ongoing task was severely disrupted after the event (Figure 3A; t(11)= −4.7, p<0.001; reduced range between 2- and 8-s endpoints), despite never before experiencing impaired performance, or the meal, at this novel time. When the event occurred at a novel time, the rats also inspected the food trough, as expected (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Event-based prospective memory is shown by putting event and time in conflict

(A) When the event was presented at a novel time, performance in the ongoing task was severely disrupted by the event. Smooth curves are the best fitting functions to the mean data shown in the figure. Data are means with 1 SEM. (B) When the event was presented at a novel time (illustrated by the horizontal bar), rats anticipated the arrival of the meal, as shown by the increase in food-trough responses when the event provided information that the meal could be obtained soon. The error bar is 1 SEM averaged across 290 min.

Probe with 3 events

Existing demonstrations of prospective memory in animals [2–5] have used tasks that arguably can be solved while continuously maintaining an active representation. Continuous activation predicts that the level of impairment will be constant or graded in a one-directional fashion (e.g., from early to late timepoints, which is compatible with the graded temporal anticipation shown in Figure 1B and in [5]). According to this view, the animals have learned a fixed sequence of anticipation (i.e., that the meal is more likely as time passes [Experiment 1] or occurs late if not early [Experiment 2]). Importantly, according to this non-prospective-memory hypothesis, the animal might form a representation of a future event and actively maintain it throughout. By contrast, event-based prospective memory would be documented by showing that the animals can specifically inactivate and subsequently reactivate the memory representation. To evaluate the hypothesis that rats activate and inactivate the memory representation in an on-demand fashion, based on the occurrence of the event, we conducted a test in which the event not only occurred in a novel temporal context, but also occurred on three occasions within the same day in the absence of a meal. If rats are capable of repeatedly activating and inactivating the memory representation, then they should show deleterious effects that are selective to the recent presentation of the event. Moreover, returning to high levels of ongoing task performance after each termination of the event would provide strong evidence that the rats inactivated the memory representation. By contrast, if impairments in ongoing task performance were based on a learned, fixed sequence, then impairments will not be selective to the presentation of the event when the event is presented repeatedly.

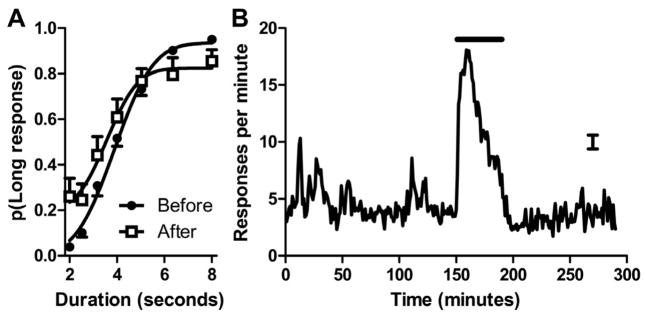

Figure 4A shows discrimination performance (range between 2- and 8-s endpoints) in three zones during which the event was absent (unfilled bars) and three zones during which the event was present (filled bars). These data strongly support event-based prospective memory because the animals are impaired when presented with the event and are not impaired at other times. These data document that we can experimentally induce the presence/absence of impairment repeatedly in an on-demand fashion by presenting the event. These data were subjected to a 2 × 3 ANOVA (2 event levels × 3 repetitions). The recent presentation of the event produced impairment relative to other timepoints when the event had not occurred (F(1,11)=9.6, p=0.01), as expected. There was no effect of repetition (F(2,22)=1.86, p=0.18) and no interaction of event presenceXrepetition (F(2,22)=2.16, p=0.14). When the event occurred at novel times, the rats also inspected the food trough, as expected (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Multiple, repeated presentations of the event on the same day demonstrate that rats inactivate and reactivate the memory representation in an on-demand, event-based fashion

(A) When the event was presented at three novel times, performance in the ongoing task was severely disrupted by the event (filled bars), with excellent performance shown at other times (unfilled bars). Events occurred at 70–89, 130–149, and 200–219 min. No-event data come from 11–20, 110–129, and 160–199 min. Data are means with 1 SEM. (B) When the event was presented at three novel time (illustrated by the horizontal bars), rats anticipated the arrival of the meal, as shown by the increase in food-trough responses when the event provided information that the meal could be obtained soon. The error bar is 1 SEM averaged across 290 min.

Our approach rules out a number of non-prospective memory alternative hypotheses. First, it is unlikely that the event directly interfered with temporal discrimination because the event was presented during the intertrial interval between successive temporal-discrimination trials; hence, the event was never present when the gap duration was presented or when the duration classification response occurred. Second, response competition between inspecting the food trough and performance in the ongoing task is unlikely to explain the severe disruption observed after the event. If high inspection rates at the trough caused impairment in ongoing-task performance (i.e., response competition), a negative correlation between rate and task performance would be expected. Contrary to this non-prospective memory hypothesis, the median inspection rate was not correlated with the decline in ongoing-task performance (r = 0.028 ± 0.212, mean ± SEM; t(11)=0.1, p=0.9; i.e., <0.0008 proportion of variance explained by response competition; data from Figures 4A and 4B). Furthermore, when the events were presented at a novel time (Figure 3), response rate decreased (t(11)= −4.3, p<0.05) while the magnitude of disruption increased (t(11)= −2.154,p=0.05) relative to the early meal, which directly contradicts the response-competition hypothesis (data from first 10 min of event). Third, satiety or fatigue are unlikely to explain our data given that impaired performance occurs at both trained early and late timepoints (Figures 2A, 2B, and 2C) as well as at novel times (Figures 3A and 4A). Fourth, it is also unlikely that the disruption in ongoing-task performance was caused by a decline in motivation to obtain small rewards in anticipation of the much larger forthcoming meal (i.e., anticipatory negative contrast). If motivation was reduced, we would expect that the latency to make a short/long classification response would increase after the event. Contrary to this prediction, rats pressed the lever faster after the event (0.77 ± 0.16 s; mean ± SEM) than at other times (1.26 ± 0.16 s; t(11)=3.0, p<0.05; data from Figure 4), an observation opposite to that predicted by anticipatory negative contrast. Aside from the approaches described above, it is not apparent how learning that the tone signals food can simultaneously produce an impairment in ongoing-task performance and an enhancement in motivation without proposing prospective memory.

Conclusions

We propose that when a meal is forthcoming but delayed, the rat forms a representation of the future action (i.e., obtaining the meal), subsequently inactivates the representation, and finally reactivates it when the appropriate event occurs. When the event was not recently presented, the rats inactivate the representation, which produced ongoing-task performance that was excellent (approximately 91%). When the event had recently been presented, the rats reactivated the representation, which produced a dramatic drop in ongoing-task performance (below 70%). Although the rats were trained with one event signaling one meal, in a number of tests with the meal withheld, the rats activated and inactivated the representation in an on-demand fashion. Importantly, the rats showed that they can repeatedly activate and inactivate the memory representation, which strongly supports the hypothesis that rats used event-based prospective memory. Whether the mechanisms of prospective memory involves spontaneous or monitoring-based retrieval is widely debated in the human literature [1], and our approach may be used to investigate these mechanisms in future studies using animals.

Four lines of evidence document the dissociation of event-based prospective memory from the use of time as a cue. First, the role of time as a cue was diminished in Experiment 2 relative to Experiment 1 by increasing the validity of event as a predictive cue. Second, the decline in ongoing task performance occurred after the event relative to an equivalent timepoint in which the event was not presented (Figure 2C). Third, ongoing task performance declined immediately after the first event (i.e., within the first 5 s since the event, which is substantially before the opportunity to time 10 min with respect to the event in Experiment 2). Fourth, presenting the event at a novel time (Figure 3A) or at three novel times (Figure 4A) produced a decline in ongoing task performance after the event despite never before experiencing impaired performance at these novel times.

The loss of memory function is debilitating. Failures of prospective memory (i.e., forgetting to act on an intention at an appropriate time in the future) is a common feature of aging [15–19] and negatively impacts health and independence (e.g., forgetting to take medications or lock one’s home) [20]. Prospective memory is impaired in several clinical populations, including patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease [21–24], Parkinson disease [25], traumatic brain injury [26–28], and HIV infection [20, 29]. Moreover, cognitive decline exerts significant societal costs. Thus, even small enhancements that retain cognitive function can have significant impacts on wellbeing, social engagement, and productivity. Because a vast range of amnesic syndromes in humans produce prominent deficits in prospective memory, development of an animal model of prospective memory may be valuable to probe the biological underpinnings of memory disorders [7, 9].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Rats “remember to remember,” documenting event-based prospective memory

Rats activate, inactivate and reactivate a memory representation of a future action

Accurate ongoing-task performance was severely disrupted when the event occurred

A representation of the future may afford the ability to plan for a future event

Acknowledgments

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Indiana University Bloomington and followed national guidelines. This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health R01MH080052 to JDC.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McDaniel MA, Einstein GO. Prospective memory: An overview and synthesis of an emerging field. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beran MJ, Evans TA, Klein ED, Einstein GO. Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) and capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) remember future responses in a computerized task. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 2012;38:233–243. doi: 10.1037/a0027796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beran MJ, Perdue BM, Bramlett JL, Menzel CR, Evans TA. Prospective memory in a language-trained chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Learn Motiv. 2012;43:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans TA, Beran MJ. Monkeys exhibit prospective memory in a computerized task. Cognition. 2012;125:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson AG, Crystal JD. Prospective memory in the rat. Anim Cogn. 2012;15:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0459-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crystal JD. Prospective cognition in rats. Learn Motiv. 2012;43:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crystal JD. Remembering the past and planning for the future in rats. Behav Process. 2013;93:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts WA. Are animals stuck in time? Psychol Bull. 2002;128:473–489. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einstein GO, Smith RE, McDaniel MA, Shaw P. Aging and prospective memory: The influence of increased task demands at encoding and retrieval. Psychol Aging. 1997;12:479–488. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith RE. The cost of remembering to remember in event-based prospective memory: investigating the capacity demands of delayed intention performance. J Exp Psychol-Learn Mem Cogn. 2003;29:347–361. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.29.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Church RM, Deluty MZ. Bisection of temporal intervals. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1977;3:216–228. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.3.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nader K. Memory traces unbound. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:65–72. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spear NE. Retrieval of memory in animals. Psychol Rev. 1973;80:163–194. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blough DS. Error factors in pigeon discrimination and delayed matching. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1996;22:118–131. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aberle I, Rendell PG, Rose NS, McDaniel MA, Kliegel M. The age prospective memory paradox: Young adults may not give their best outside of the lab. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:1444–1453. doi: 10.1037/a0020718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.d’Ydewalle G, Bouckaert D, Brunfaut E. Age-related differences and complexity of ongoing activities in time- and event-based prospective memory. Am J Psychol. 2001;114:411–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driscoll I, McDaniel MA, Guynn MJ. Apolipoprotein E and prospective memory in normally aging adults. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:28–34. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henry JD, MacLeod MS, Phillips LH, Crawford JR. A meta-analytic review of prospective memory and aging. Psychol Aging. 2004;19:27–39. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craik FIM. A functional account of age differences in memory. In: Hagendorf FKH, editor. Human memory and cognitive capabilities: Mechanisms and performances. North Holland: Elsevier; 1986. pp. 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods SP, Dawson MS, Weber E, Gibson S, Grant I, Atkinson JH. Timing is everything: Antiretroviral nonadherence is associated with impairment in time-based prospective memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15:42–52. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708090012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanco-Campal A, Coen RF, Lawlor BA, Walsh JB, Burke TE. Detection of prospective memory deficits in mild cognitive impairment of suspected Alzheimer’s disease etiology using a novel event-based prospective memory task. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15:154–159. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708090127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones S, Livner Å, Bäckman L. Patterns of prospective and retrospective memory impairment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2006;20:144–152. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Troyer AK, Murphy KJ. Memory for intentions in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Time- and event-based prospective memory. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:365–369. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitter-Edgecombe M, Woo E, Greeley DR. Characterizing multiple memory deficits and their relation to everyday functioning in individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:168–177. doi: 10.1037/a0014186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raskin SA, Woods SP, Poquette AJ, McTaggart AB, Sethna J, Williams RC, Tröster AI. A differential deficit in time- versus event-based prospective memory in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:201–209. doi: 10.1037/a0020999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry JD, Phillips LH, Crawford JR, Kliegel M, Theodorou G, Summers F. Traumatic brain injury and prospective memory: Influence of task complexity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2007;29:457–466. doi: 10.1080/13803390600762717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCauley SR, McDaniel MA, Pedroza C, Chapman SB, Levin HS. Incentive effects on event-based prospective memory performance in children and adolescents with traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:201–209. doi: 10.1037/a0014192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mateer CA, Sohlberg MM, Crinean J. Focus on clinical research: Perceptions of memory function in individuals with closed-head injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1987;2:74–84. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Grant I. Prospective Memory in HIV-1 Infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2006;28:536–548. doi: 10.1080/13803390590949494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.