Abstract

Blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a widely used method for brain mapping. BOLD fMRI signal detection is based on an intravoxel dephasing mechanism. This model involves bulk nuclear spin precession in a BOLD-induced inhomogeneous magnetic field within a millimeter-resolution voxel, that is, BOLD signal formation spans a huge spatial scale range from Angstrom to millimeter. In this letter, we present a computational model for multiresolution BOLD fMRI simulation, which consists of partitioning the nuclear spin pool into spin packets at a mesoscopic scale (~10−6m), and calculating multiresolution voxel signals by grouping spin packets at a macroscopic scale range (10−5-10−3m). Under a small angle approximation, we find that the BOLD signal intensity is related to its phase counterpart (or BOLD fieldmap) across two spatial resolution levels.

Keywords: Multiresolution BOLD fMRI, spin packet, intravoxel dephasing, phasor, small angle approximation

I. Introduction

Currently, the spatial resolution of BOLD fMRI typically assumes millimeter or submillimeter range which is far larger than the atomic dimension (at 10−10m or Angstrom scale) of nuclear spins. Spanning a huge spatial scale range from a microscopic molecular level to a macroscopic voxel level, the BOLD fMRI signal is formed by an intravoxel dephasing mechanism, which involves microscopic spin precessions in a BOLD-induced inhomogeneous magnetic field, as governed by the Larmor law. Although the BOLD contrast mechanism (T2* contrast) has been widely accepted for neuroimaging and brain mapping, there is still a lack of complete understanding of the interplay of biophysics and MRI technology. In this work we present a computational model that enables a numerical simulation to address several key aspects of the BOLD signal formation.

BOLD signal simulations have previously been implemented by representing a vasculature-laden voxel (at submillimeter scale) with a support matrix (at micron scale) and calculating the voxel signal via the intravoxel dephasing model[1-9]. In this letter, we will report on a computational multiresolution BOLD fMRI model, in particular, we will shed light on the strategy of dealing with the spatial scale span (from atomic scale to millimeter scale) via a spin packet model [10]. Under a small angle condition [11], we find that the signal intensity can be related to its phase counterpart (or fieldmap, which is different from the phase image by a constant factor) by a two-resolution-level relationship. We demonstrate a 4-level multiresolution BOLD fMRI simulation through recursive voxel decompositions in a scale range of 105-10−3m.

II. MODEL and Theory

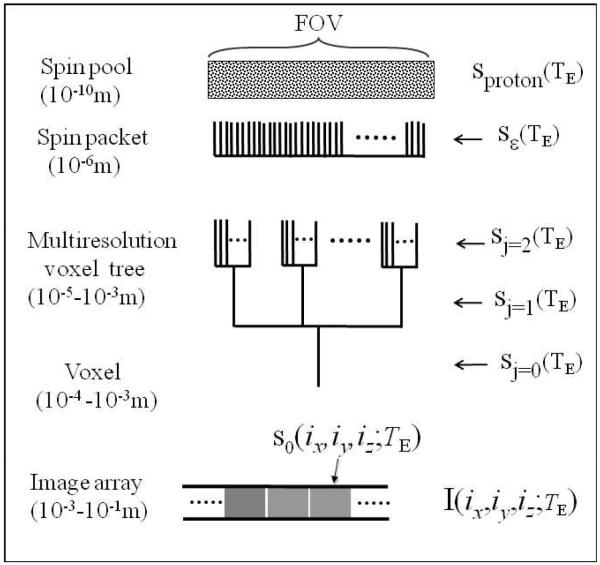

Overall, we propose a computational multiresolution BOLD fMRI model in Fig. 1, in which a voxel signal spans a scale range from 10−10m-10−3m, and the multiresolution voxels are manipulated in a scale range from 10−5m-10−3m. In the following, we present an approach to handle the multiscale issues.

Fig. 1.

Overall model for computational multiresolution BOLD fMRI. The field view (FOV) is depicted by a spin pool. A grid resolution ε is used to partition the spin pool into a finite number of gridels. The numerous nuclear spins inside a gridel is modeled as a spin packet. Multiresolution voxels and BOLD signals are implemented through the manipulation on the gridels and spin packets. The FOV image is presented by an array of voxels.

A. From nuclear spins to spin packet

The fundamental NMR principle consists of nuclear spin (proton spin) and spin precession in magnetic field. At the microscopic atomic scale (extent ~10−10m or Angstrom), a single proton (which has a spin magnetic moment), when exposed to a magnetic field, undergoes a precession at an angular speed as determined by the Larmor law. In the rotating frame, a proton spin precession signal is expressed by

| (1) |

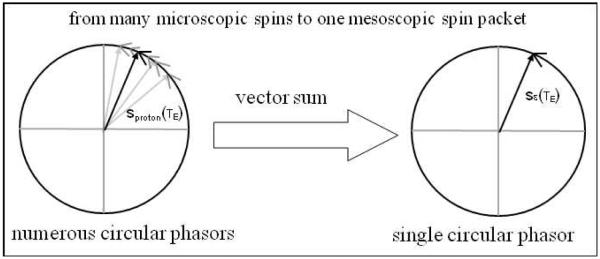

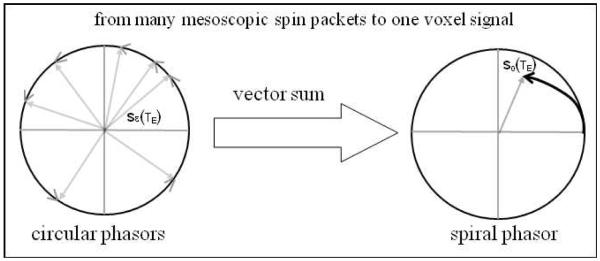

where ΔB(x,y,z) denotes the field perturbation, or the so-called fieldmap, and TE the relaxation time, and γ the gyromagnetic ratio. Since there are a large number of protons (as estimated by the Avogadro constant 6.02×1023 /mole) in a millimeter-resolution voxel (close to a typical BOLD voxel dimension), depicted by “spin pool” in a field of view (FOV) in Fig.1, it is impossible to count them. For numerical simulation of BOLD fMRI, we always need to partition the continuous FOV space into an array of voxels, and represent reach voxel by a support matrix at a grid resolution. We describe the tiny matrix element by “gridel” and simplify the proton spins inside a gridel by a “spin packet” [10, 11]. Fig. 2 illustrates the spin packet model: the vector sum of numerous proton spin processions inside a gridel is modeled by a single equivalent spin. It is noted that, in the phasor diagram, both proton precession and spin packet procession are represented by unit circular phasors, implying no amplitude decay: |sproton(TE)|=1 and |sε(TE)|=1.

Fig. 2.

Phasor diagram for spin packet model: the vector sum of numerous spins inside a gridel produces a single equivalent spin.

Let ε denote the grid resolution (~micronmeter), Ωε=ε×ε×ε the gridel, ΔB(x,y,z) the field perturbation, and (ix,iy,iz) the discretization of (x,y,z), then the spin packet precession signal is expressed by

| (2) |

The spin packet model in Eq. (2) serves as a bridge from microscopic nuclear spins (at atomic scale) to mesoscopic spin packet (at micron scale), which enables numerical simulation of BOLD fMRI. It is noted that there is an intra-gridel average associated with Eq. (2). As ε reduces, the average effect diminishes.

B. From spin packets to voxel signal and image array

Assume a voxel at a macroscopic millimeter scale, its signal is formed by the intravoxel dephasing summation as given by

| (3) |

Fig. 2 illustrates the intravoxel dephasing mechanism in Eq. (3): the vector sum of spin packets in voxel produces a voxel signal. Due to precession dephasing among the spin packets, the voxel signal exhibits magnitude decay, i.e. |s0(TE)|≡|S0(TE)/S0(TE=0)|<1, and phase angle accumulation, i.e., ∠s0(TE)∞ΔB·TE with respect to TE.

C. Grouping spin packets for multiresolution BOLD signals

The coarse-to-fine multiresolution voxel decomposition can be implemented by spatially partitioning a voxel (parent voxel) into smaller subvoxels (child voxels). The child voxel signal is calculated by

| (4) |

which is identical to Eq. (3) except that a smaller number of spin packets in Ωj are involved in the summation. By grouping the smaller child voxels into a larger parent voxel, we implement fine-to-coarse multiresolution voxel synthesis. For a J-level multiresolution voxel decomposition, we obtain an octree [12] for the multiresolution BOLD signals, as represented by

| (5) |

where K8 denotes the set of eight child labels, and (1k,2k,..,jk) the notation for tree node labels. The BOLD signal at the root S0(TE) is composed of all the sibling signals at a lower level j, that is

| (6) |

The BOLD signals across two resolution levels in an octree in Eq.(5) are governed by

| (7) |

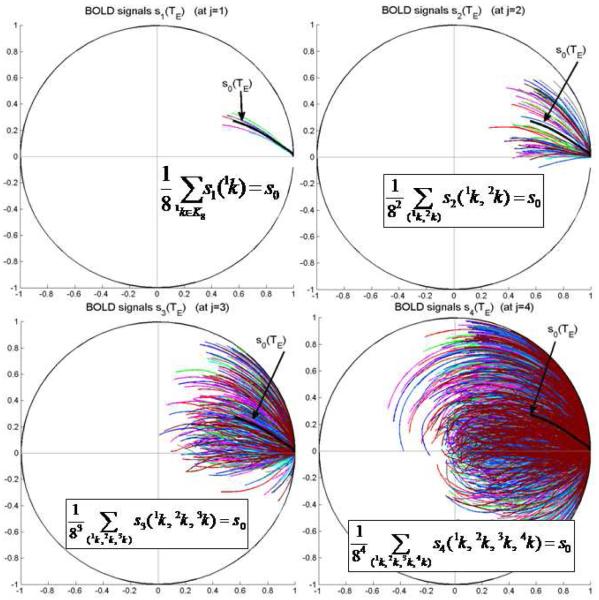

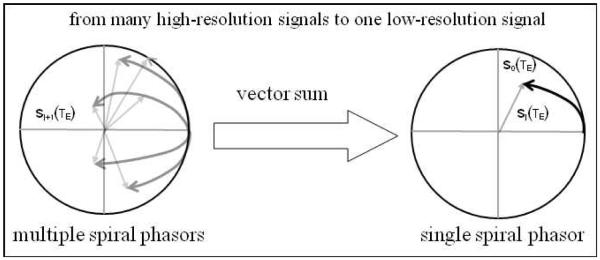

In Fig. 4, we illustrate the two-level fine-to-coarse multiresolution BOLD signal synthesis: the vector sum of a multitude of child spiral phasors produces a parent spiral phasor. Due to summation, the parent phasor is usually shorter and more stable than the child phasors (as will be demonstrated later).

Fig. 4.

Phasor diagram for multiresolution BOLD signal synthesis. The vector sum of child voxel signals produce a parent voxel signal. All signals are normalized by sj(TE)=Sj(TE)/Sj(TE=0).

By spatially assembling the multivoxel signals, we obtain a dataset I(ix,iy,iz;TE) for the FOV. In this way we build up the multiresolution BOLD fMRI model in Fig. 1. The implementation procedures are summarized as follows: we handle the microscopic nuclear spins by a mesoscopic spin packet model, calculate the BOLD signals at different resolution levels by summing up the spin packets, and render the multiresolution signals or images by merging or decomposing the voxel signals. State-of-the-art, high resolution (and high field) BOLD fMRI (assuming a voxel dimension range in 10−4-10−3m) has been accomplished [13, 14], and ultrahigh resolution BOLD fMRI (10−5-10−4m) is under pursuit. Based on the spin packet model and multiresolution voxel decomposition/synthesis in Fig. 1, we can implement multiresolution BOLD fMRI across a scale range of 10−6-10−3m.

D. Magnitude and phase relations across two resolution levels

The multiresolution BOLD signals are governed by Eqs. (6) and (7), which show that the vector sum of high-resolution complex signals produces a low-resolution complex signal provided that the high-resolution subvoxels are a spatially disjoint partition of the low-resolution voxel. This statement is valid for un-normalized signals. For normalized signals (by setting the signal to start at 1at TE=0), we have

| (8) |

The multiresolution signal normalizations by Eq.(8) mean that all the complex signals at multiresolution levels are depicted with phasors within a unit circle (see Fig. 4 and Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Demonstration of 4-level multiresolution BOLD signals for a cortical voxel (filled with 3-micron-radius vasculature under the condition of 2% blood volume fraction). All the BOLD signals are normalized at TE=0. It is noted that, as the spatial resolution increases, the phasors prolong and some of them exhibit disordered spirals. The phasors are colored for visual distinction.

In practice, we always need to examine the magnitude and phase components of a complex signal, that is S(TE) = A(TE)exp(-iΦ(TE)). Since the magnitude and phase coordinates of a complex signal are curvilinear orthogonal, that is, |Sj(TE)| = |Aj(TE)exp(−iΦj(TE))| = Aj(TE) is independent of ∠S(TE) =−Φj(TE), therefore, there is no explicit relationship between the magnitude and phase pair of a complex signal at the same resolution level. In fact, the BOLD signal is formed through an intravoxel dephasing summation as shown in Eq. (3) and with the source of inhomogenous field ΔB(x,y,z), we observe that there must be some relationship between magnitude and phase of the complex signal (albeit approximate and implicit). By examining the signal behaviors across different resolutions, we find such a relationship as presented below.

If the phase angle Φ is small such that Φ<<1, we may make 1st and 2nd order approximations for exp(−iΦ) by

| (9) |

Considering the fact that there is a smaller spatial average effect on a child voxel than on a parent voxel, we suggest applying 1st and 2nd order approximations to the parent and child signals respectively. In doing so, we obtain the following two-resolution relations

| (10) |

which shows that the amplitude and phase pairs of BOLD signals interplay across two multiresolution levels. In practice, given a signal phase S(TE), we may use it to calculate the magnetic field value via ∠S(TE)=Φ( TE) ≈ γ· TE ·ΔB. By applying another approximation Φj+1(TE) ≈ (ΔB)j+1·γ·TE to Eq.(10), we obtain

| (11) |

which reveals a fact that the fieldmap variance among the child voxels is explicitly related to the differences of the two-resolution signal magnitudes. Therefore, the relationship in Eq. (11) suggests a way to detect the fieldmap variance (rather than the fieldmap distribution itself) via a two-resolution experiment.

III. Demonstration

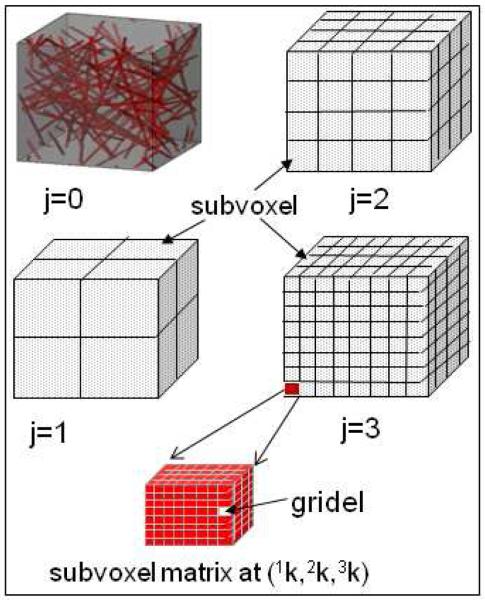

Figure 5 illustrates a multiresolution vasculature-laden voxel decomposition (see [15] for cortical voxel configuration). With the following parameter settings: cortical voxel = 320×320×320 micron3, vessel radius=3micron, blood volume fraction=2%, grid resolution =0.625micron; field strength B0=3T; BOLD activity Δχ=0.5ppm; relaxation time TE=[0,120]ms, we implemented a 4-level multiresolution BOLD fMRI signal. The normalized complex BOLD signals (see Eq.(8)) are demonstrated in the phasor diagram shown in Fig. 6. The 4-level voxel sizes are in the order of 320×320×320, 160×160×160, 80×80×80, 40×40×40, 20×20×20 micron3.

Fig. 5.

Illustration of multiresolution voxel decomposition. The root voxel is filled with 3-micron-radius vessel network. A parent voxel is decomposed eight child voxels. The gridels are the building blocks for all voxels and subvoxels.

IV. Discussion and conclusion

Space discretization is a necessary step for computational BOLD fMRI simulation. We discretize a cortical voxel space with a small grid resolution (~0.625micron in our demonstration), and thereby represent the voxel by a support matrix consisting of tiny gridels. We simplify the aggregation of numerous nuclear spins inside a gridel by a spin packet (there is no dephasing inside a gridel). Accurate simulation demands as-tiny-as-possible gridels for two reasons: one reason is for accurate digital geometry of the voxel space and intravoxel vasculature; another is to reduce the intra-gridel integration effect inherent to the discretiazion in Eq.(2).

For a BOLD fMRI dataset acquired at one spatial resolution, there is no explicit relationship between the signal magnitude (intensity) to its phase counterpart (fieldmap) due to the curvilinear coordinate orthogonality of a polar-coordinate system. Through multiresolution signal analysis, we find a way to relate the signal magnitudes across two resolution levels under small angle conditions. The violation of small angle condition (due to high field, long relaxation time, high spatial resolution, or their combination) will result in disordered phasor evolutions (see the panel for j=4 in Fig. 6).

In summary, in this letter, we present a framework for multiresolution BOLD fMRI simulation. Specifically, a coarse-to-fine multiresolution strategy can be implemented by partitioning the field of view (FOV) into voxels, discretizing a voxel into a matrix by tiny gridels (at a grid resolution), and decomposing a voxel into subvoxels. The spin packet model serves as a bridge at the mesoscopic micron-meter scale (~micron) that links the microscopic nuclear spins (~Angstrom) to the macroscopic image and voxel signals (~millimeter). Considering the gridels as building blocks, we can group them into voxels and subvoxels and calculate the multiresolution BOLD signals by summing up the spin packets therein. We demonstrate the coarse-to-fine multiresolution BOLD fMRI signal simulation by spatially partitioning a voxel into eight subvoxels, and continuing the recursive octadic subvoxel decomposition through 4 levels. We find that high resolution BOLD fMRI may reveal new signal behavior (such as phasor prolongation and disordered evolutions) that are suppressed in low resolution imaging (due to averaging across a large voxel). Based on a small angle approximation and multiresolution signal analysis, we find that the BOLD signal magnitude can be related to its phase counterpart across multiresolution levels, which is not explicitly available at the same resolution level. For a general case (not limited to a small angle condition), an empirical relationship may be obtained via computational simulation and by phantom experiments. It is expected that further study of multiresolution signal behavior and magnitude/phase relationships will improve neuroimaging and brain mapping.

Fig. 3.

Phasor diagram for intravoxel dephasing summation in Eq.(3). The vector sum of spin packets inside a voxel produces a voxel signal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NSF grants #0715022 & 0840895 and an internal grant (#6003-154 of DE-FG02-08ER64581) at the Mind Research Network.

Contributor Information

Zikuan Chen, Mind Research Network, Albuquerque, NM 87106. (zchen@mrn.org).

Vince Calhoun, Mind Research Network and the Electrical Computer Engineering Department, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131 (vcalhounn@mrn.org).

References

- [1].Boxerman JL, et al. The intravascular contribution to fMRI signal change: Monte Carlo modeling and diffusion-weighted studies in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 1995 Jul;34:4–10. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Boxerman JL, et al. MR contrast due to intravascular magnetic susceptibility perturbations. Magn Reson Med. 1995 Oct;34:555–66. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kennan RP, et al. Intravascular susceptibility contrast mechanisms in tissues. Magn Reson Med. 1994 Jan;31:9–21. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Marques JP, Bowtell RW. Using forward calculations of the magnetic field perturbation due to a realistic vascular model to explore the BOLD effect. NMR Biomed. 2008 Jul;21:553–65. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Martindale J, et al. Theory and generalization of Monte Carlo models of the BOLD signal source. Magn Reson Med. 2008 Mar;59:607–18. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Menon RS. Simulation of BOLD phase and magnitude changes in a voxel. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 2003;11:1719. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ogawa S, et al. Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging. A comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophys J. 1993 Mar;64:803–12. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pathak AP, et al. A novel technique for modeling susceptibility-based contrast mechanisms for arbitrary microvascular geometries: the finite perturber method. Neuroimage. 2008 Apr 15;40:1130–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rowe DB. Modeling both the magnitude and phase of complex-valued fMRI data. Neuroimage. 2005 May 1;25:1310–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen Z, Calhoun VD. Magnitude and Phase Behavior of Multiresolution BOLD signal. Concepts Magn Reson. 2010;37B doi: 10.1002/cmr.b.20164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chen Z, et al. SPIE Medical Imaging. Vol. 7961. Orlando, FL: Feb 2011, Multiresolution voxel decomposition of complex-valued BOLD signals reveals phasor turbulence; p. 79613y. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen Z, Ning R. Forest representation of vessels in cone-beam computed tomographic angiography. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2005 Jan;29:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Thomas BP, et al. High-resolution 7T MRI of the human hippocampus in vivo. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008 Nov;28:1266–72. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sudhyadhom A, et al. A high resolution and high contrast MRI for differentiation of subcortical structures for DBS targeting: The Fast Gray Matter Acquisition T1 Inversion Recovery (FGATIR) Neuroimage. 2009 Apr 10; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen Z, et al. Effect of surrounding vasculature on intravoxel BOLD signal. Med Phys. 2010;37:10. doi: 10.1118/1.3366251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]