Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) is a universal second messenger important for T lymphocyte homeostasis, activation, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The events surrounding Ca2+ mobilization in lymphocytes are tightly regulated and involve the coordination of diverse ion channels, membrane receptors, and signaling molecules. A mechanism termed store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), causes depletion of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ stores following T cell receptor (TCR) engagement and triggers a sustained influx of extracellular Ca2+ through Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels in the plasma membrane. The ER Ca2+ sensing molecule, stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), and a pore-forming plasma membrane protein, ORAI1, have been identified as important mediators of SOCE. Here, we review the role of several additional families of Ca2+ channels expressed on the plasma membrane of T cells that likely contribute to Ca2+ influx following TCR engagement, particularly highlighting an important role for voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (CaV) in T lymphocyte biology.

Keywords: calcium, T cell, calcium channels, L-type calcium channels, T cell signaling

In the body’s steady-state, a pool of T lymphocytes that express a diverse T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire is maintained in the periphery. In the event of an infection, T lymphocytes, through their TCR, recognize the infectious antigen and are activated and subsequently induced to proliferate and differentiate into effector cells capable of clearing the pathogen. Key components of the signaling events mediating T lymphocyte development, differentiation, homeostasis, effector function, and cell death are the universal second messenger calcium (Ca2+) and the Ca2+ channels that regulate the intracellular Ca2+ levels (Smith-Garvin et al., 2009).

The activation of a T cell occurs when its TCR recognizes cognate antigen presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) by an antigen processing cell. In primary immune responses, this is the function of dendritic cell (DC). DCs take up soluble and particulate antigen as well as cellular debris by phagocytosis, endocytosis, or macropinocytosis and degrade them in endolysosomal compartments where liberated foreign antigens, usually peptides, are subsequently loaded onto MHC-I or MHC-II molecules that cycle to the plasma membrane. Here, the MHC/foreign antigen complex is recognized by a cognate TCR expressed on a specific T lymphocyte (Vyas et al., 2008). A series of signaling events ensue following ligation of the TCR. Ca2+ is critical to the TCR signaling processes. TCR engagement triggers an increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels resulting from the activation of phospholipase Cγ1 (PLCγ1) and the associated hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol-3,4-bisphosphate (PIP2) into inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 binds to IP3 receptors (IP3R) in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) causing release of ER Ca2+ stores into the cytoplasm. During the event of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), depletion of ER Ca2+ stores triggers a sustained influx of extracellular Ca2+ through Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ (CRAC) channels in the plasma membrane (Hogan et al., 2010).

The sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+ results in the activation of signaling molecules and transcription factors that induce expression of genes required for T cell activation, proliferation, differentiation, and effector function. In T cells, Ca2+ can activate a variety of targets including the serine/threonine phosphatase calcineurin and its transcription factor target nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) and its target cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB), myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) targeted by both calcineurin and CaMK, and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) (Oh-Hora, 2009). The best studied downstream effect of Ca2+ is the calcineurin-NFAT pathway. Increased Ca2+ levels promote the binding of Ca2+ to calmodulin inducing a conformational change that allows calmodulin to bind and activate calcineurin. Calcineurin dephosphorylates serines in the amino-terminus of NFAT exposing a nuclear localization signal. This results in the transport of NFAT into the nucleus, where NFAT can interact with other transcription factors, integrating signaling pathways, and inducing gene expression patterns dependent on the context of the TCR signaling (Hogan et al., 2003; Macian, 2005; Smith-Garvin et al., 2009). Ca2+ has also been proposed to regulate the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in T cells. RasGRP that activates Ras not only has a DAG binding domain but also has a pair of EF-hand motifs that can directly bind Ca2+ (Cullen and Lockyer, 2002). Through this interaction, activation and membrane localization of Ras guanyl nucleotide-releasing protein (RasGRP) is influenced. Upon weak TCR stimulation, RasGRP localizes to the Golgi membrane whereas strong TCR signaling results in recruitment to the plasma membrane. The site of activation may play a role in what extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) can target downstream thereby contributing to differential signaling dependent on the stimulus (Teixeiro and Daniels, 2010).

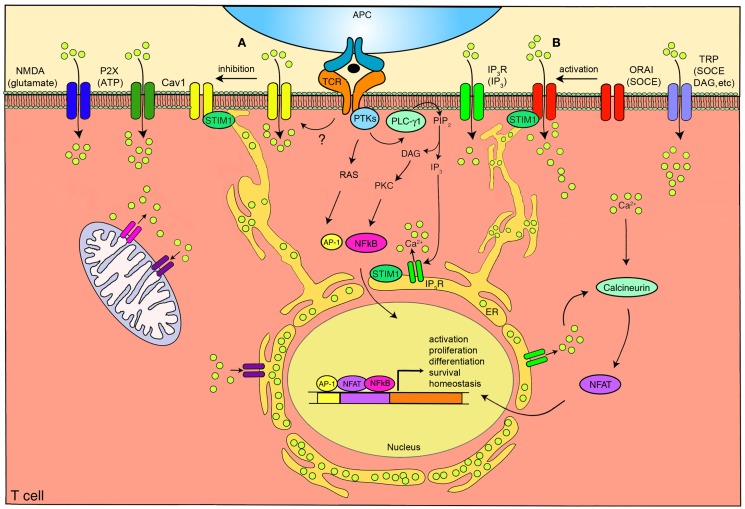

There are several families of channels expressed on the plasma membrane of T lymphocytes (Kotturi et al., 2006) that may play important roles in Ca2+ entry (Figure 1). Recently, through genome wide high-throughput RNA interference screens and analysis of patients with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), a pore-forming plasma membrane protein, ORAI1 (Feske et al., 2006; Vig et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006), and an ER Ca2+ sensing molecule, stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) (Liou et al., 2005; Roos et al., 2005), have been identified as the classically defined CRAC channel. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels have also been the focus of much attention and have been reported to be activated by store depletion in T cells. IP3 receptors (IP3R), similar to the ER-associated Ca2+ channels, have been shown to be expressed at the plasma membrane of T cells. In addition, T cell expressed adenosine triphosphate (ATP) responsive purinergic P2 (P2X) receptors and glutamate mediated N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) activated receptors have shown significant Ca2+ permeability. Finally, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (CaV), the focus of this review, have been identified to play a crucial function in T cells (Omilusik et al., 2011).

Figure 1.

The calcium channels in T cells. T cell receptor (TCR) engagement by a peptide-MHC on an antigen presenting cell (APC), induces protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) to activate phospholipase C-γ1 (PLC-γ1), which cleaves phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) from plasma membrane phospholipids to generate diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). Elevated levels of IP3 in the cytosol leads to the release of Ca2+ from IP3R Ca2+ channels located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Ca2+ depletion from the ER induces Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space through the plasma membrane channel, ORAI1. Several auxiliary channels also operate during TCR-mediated Ca2+ signaling. These include plasma membrane IP3R activated by the ligand IP3, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels that can be operated by DAG and store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), adenosine triphosphate (ATP) responsive purinergic P2 (P2X) receptors, glutamate mediated N-methyl-D-aspartate activated (NMDA) channels, and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (CaV1) that may be regulated through TCR signaling events. The mitochondria also control cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. Increase in intracellular Ca2+ results in activation of calmodulin-calcineurin pathway that induces nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) nuclear translocation and transcription of target genes to direct T cell homeostasis, activation, proliferation, differentiation, and survival. Within this complex network of Ca2+ signaling, a model of the reciprocal regulation of CaV1 and ORAI1 in T cells has been proposed. (A) Low-level TCR signaling through interactions with self-antigens (i.e., self-peptides/self-MHC molecules) may result in CaV1 (particularly CaV1.4) activation and Ca2+ influx from outside the cell. This allows for filling of intracellular stores and initiation of a signaling cascade to activate a pro-survival program within the naïve T cell. Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) is not activated in this scenario and, consequently, ORAI1 remains closed. (B) Strong TCR signaling through engagement by a foreign peptide-MHC induces the downstream signaling events that result in ER Ca2+ store depletion and STIM1 accumulation in puncta in regions of the ER near the plasma membrane allowing interactions with Ca2+ channels. ORAI1 enhances STIM1 recruitment to the vicinity of CaV1 channels. Here, STIM1 can activate ORAI1 while inhibiting CaV1. PKC, protein kinase C. AP-1, activating protein-1. NFκB, nuclear factor kappa B. Yellow circles, Ca2+.

ORAI and STIM

The discovery of the pore-forming plasma membrane proteins, ORAI1 and homologs ORAI2 and ORAI3, and the ER Ca2+ sensors, STIM1 and STIM2, has led to the development of a well-established paradigm of their coordinated action (Hogan et al., 2010; Feske et al., 2012; Srikanth and Gwack, 2012). TCR engagement triggers the generation of IP3 and the subsequent activation of IP3Rs that mediate the release of Ca2+ from the ER. The ER transmembrane protein, STIM1, can sense the depletion of Ca2+ stores. STIM1 exists as a monomer when Ca2+ is present, and its conformation is stabilized through an interaction between its luminal EF-hand domain and sterile α-motif (SAM). When ER Ca2+ stores are depleted, the EF-SAM domain interaction in STIM1 becomes unstable resulting in the oligomerization of STIM1 molecules (Park et al., 2009; Stathopulos et al., 2009). STIM1 oligomers accumulate in puncta in regions of ER 10–25 nm beneath the plasma membrane (Liou et al., 2005, 2007; Wu et al., 2006a). Here, ORAI1 at the plasma membrane can interact with STIM1 (Luik et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2006). ORAI1 has been suggested to exist as a dimer in the plasma membrane and upon STIM1 interaction forms tetramers that can function to import Ca2+ (Penna et al., 2008).

Analyses of ORAI1 and STIM1 deficiency in human patients, that initially led to the identification of ORAI (Feske et al., 2006), as well as in mouse models, have validated their physiological role in T cell activation. In humans, loss of functional ORAI1 or STIM1 results in SCID (Partiseti et al., 1994; Le Deist et al., 1995; Feske et al., 2001, 2005, 2006; Picard et al., 2009). While lymphocyte numbers are normal in these patients, impaired SOCE leaves T cells with diminished ability to proliferate and produce cytokines upon activation. Analogous phenotypes are observed in animal models. In ORAI1−/− and STIM1−/− mice, thymic development of conventional TCRαβ T cells appears normal. However, impaired selection of agonist-selected T cells, T regulatory cells (Treg), invariant natural killer T cells and TCRαβ+ CD8αα+ intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, owing to a defect in IL-2 or IL-15 signaling has been noted in STIM1- and STIM2-deficient mice (Oh-Hora et al., 2013). ORAI1-deficiency causes a moderate reduction in SOCE and subsequent cytokine production in T cells (Gwack et al., 2008; Vig et al., 2008). STIM1-deficient T cells have no CRAC channel function or SOCE, no subsequent activation of NFAT transcription factor and, as a result, have impaired cytokine secretion (Oh-Hora et al., 2008). This impacts T cell responses and, consequently, confers protection from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) due to poor generation of Th1/Th17 responses (Schuhmann et al., 2010).

Interestingly, STIM-deficiency is also associated with lymphoproliferative and autoimmune diseases. In SCID patients, this is seen as lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes) and hepatosplenomegaly (enlarged liver and spleen) as well as autoimmune hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia resulting from immune responses directed against the red blood cells and platelets, respectively (Picard et al., 2009). It has been suggested that this autoimmunity observed in STIM1-deficient patients is a consequence of the reduced Treg cell numbers found in the periphery (Feske, 2009; Picard et al., 2009). Similarly, mice lacking both STIM1 and STIM2 experienced autoimmune and lympho-myeloproliferative syndromes again due to a severe reduction in Treg number in the thymus and secondary lymphoid organs and impaired Treg suppressive function (Oh-Hora et al., 2008). This Treg deficiency is presumably a result of poor Ca2+/NFAT-dependent induction of Foxp3 expression (Wu et al., 2006b; Oh-Hora et al., 2008; Tone et al., 2008). Together, these studies highlight the importance of ORAI1/STIM1 in T cell activation and immune tolerance.

T cells also express family members ORAI2 and ORAI3 that exhibit similar structure to ORAI1. ORAI2 and ORAI3 form Ca2+-permeable ion pores; however, these channels differ in their pharmacology, ion selectivity, activation kinetics, and inactivation properties in comparison to ORAI1 (Lis et al., 2007). Overexpression of ORAI2 or ORAI3 with STIM1 can result in Ca2+ currents similar but not identical to the CRAC current (DeHaven et al., 2007; Lis et al., 2007). However, ORAI2’s contribution to Ca2+ signaling in differentiated T cells is questionable as overexpression of ORAI2 in ORAI1−/− T cells does not restore SOCE (Gwack et al., 2008). ORAI2 expression is high in naïve T cells and is down regulated upon activation; therefore, ORAI2 may have a major role in development or peripheral homeostasis (Gwack et al., 2008; Vig et al., 2008). ORAI3 has been shown to form pentamers with ORAI1 to make up the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels (Mignen et al., 2009). These channels are activated by arachidonic acid rather than store-depletion and require plasma membrane localized STIM1 for their regulation (Mignen et al., 2007). Their role in T cells has yet to be determined.

STIM2 with 42% sequence similarity to STIM1 is also found in T cells. While STIM1 has relatively high and constant expression and can be found to some extent in the plasma membrane as well as the ER, STIM2 is expressed at low levels in naïve T cells but is upregulated upon TCR activation and is exclusively localized to the ER (Williams et al., 2001; Soboloff et al., 2006). Like STIM1, STIM2 functions as an ER Ca2+ sensor and is able to mediate SOCE in lymphocytes. Nevertheless, STIM2 does not seem to serve a redundant purpose as its overexpression only partially rescues Ca2+ influx deficiency in STIM1−/− T cells (Brandman et al., 2007; Oh-Hora et al., 2008). Upon Ca2+ store depletion, STIM2 also oligomerizes and localizes to puncta at ER-plasma membrane contacts; however, STIM2 detects smaller decreases in ER Ca2+ concentration and forms multimers with slower kinetics than STIM1 with some STIM2 already activated in resting cells with replete Ca2+ stores (Soboloff et al., 2006; Brandman et al., 2007). This fits with the established role for STIM2 in regulating basal Ca2+ influx and stabilizing cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels in resting cells (Brandman et al., 2007). It also explains the fact that STIM2-deficiency has minimal effect on the initial Ca2+ entry but impairs the ability of T cells to maintain nuclear translocation of NFAT and cytokine production (Oh-Hora et al., 2008). Where STIM1 readily senses ER Ca2+ store depletion and can initiate SOCE, STIM2 remains active in higher Ca2+ levels when stores are refilling and can sustain the response (Oh-Hora, 2009).

Although the details of the ORAI-STIM pathway have been the subject of a large amount of recent work, this scheme does not account for the involvement of other currents mediated by additional plasma membrane Ca2+ channels that have been shown to be expressed and function in T cells (Kotturi et al., 2003; Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005; Omilusik et al., 2011), nor does it allow for differential patterns in Ca2+ response between T cell subsets (Fanger et al., 2000; Weber et al., 2008; Robert et al., 2011). Immunologists are only beginning to acknowledge, accept, and integrate these channels into the pantheon of functions mediated by T cells. Therefore, incorporating multiple Ca2+ channels into a comprehensive model is essential for the complete understanding of Ca2+ signaling in T cells.

Important Additional Ca2+ Channels in T Lymphocytes

IP3 receptors

The IP3Rs, similar to those found in the ER, have been suggested to function as Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane (Khan et al., 1992; Kotturi et al., 2006). IP3 dissipates rapidly after TCR engagement; therefore, IP3 induced activation of plasma membrane receptors would only contribute to short-term Ca2+ signaling (Kotturi et al., 2006). Alternatively, it was suggested that IP3Rs in the ER, known to bind IP3 to deplete ER Ca2+ stores, change conformation upon ER store depletion, and signal to surface IP3Rs to open (Berridge, 1993). IP3Rs have been identified on the cell surface of cultured T cells (Khan et al., 1992; Tanimura et al., 2000). However, IP3-induced Ca2+ currents across the plasma membrane could not be detected (Zweifach and Lewis, 1993). As an alternate function based on the numerous protein binding sites present in the modulatory domain of the channel, IP3Rs have been proposed to operate at the plasma membrane as scaffolds (Patterson et al., 2004). Further work is required to clearly fit the IP3R into the Ca2+ signaling network in T cells.

Transient receptor potential channels

The first TRP family member was discovered in Drosophila and was found to have a role in visual transduction (Montell and Rubin, 1989). Subsequently, 28 mammalian TRP channel proteins have been identified. These are grouped into six subfamilies based on amino acid sequence similarities: the classical TRPs (TRPCs) that are most similar to Drosophila TRP; the vanilloid receptor TRPs (TRPVs); the melastatin TRPs (TRPMs); the mucolipins (TRPMLs); the polycystins (TRPPs); and ankyrin transmembrane protein 1 (TRPA1) (Clapham et al., 2003; Montell and Rubin, 1989). The six transmembrane domain TRP channels form pores that are permeable to cations including Ca2+ (Owsianik et al., 2006). Various TRP channel family members have been shown to be expressed in cultured or primary T cells (Schwarz et al., 2007; Oh-Hora, 2009; Wenning et al., 2011).

Before the discovery of ORAI1 and STIM1, TRP channels were investigated as candidates for the CRAC channel. The TRPV6 channel is highly permeable to Ca2+ and has been shown to be activated by store-depletion (Cui et al., 2002). In addition, when a dominant-negative pore-region mutant of TRPV6 was expressed in Jurkat T cells, the CRAC current was diminished (Cui et al., 2002). However, in subsequent studies, the CRAC channel inhibitor, BTP2, had no effect on TRPV6 channel activity (Zitt et al., 2004; He et al., 2005; Schwarz et al., 2006) and the role of TRPV6 as a CRAC channel could not be confirmed (Voets et al., 2001; Bodding et al., 2002). TRPC3 channels were also under consideration as CRAC channels following the discovery that Jurkat T cell lines with mutated TRPC3 channels had reduced Ca2+ influx following TCR stimulation. This impairment could be overcome by overexpression of a wild-type TRPC3 (Fanger et al., 1995; Philipp et al., 2003). Furthermore, siRNA knockdown of TRPC3 expression in human T cells resulted in reduced proliferation following TCR stimulation (Wenning et al., 2011). However, while TRPC3 has been shown to be activated in response to store-depletion (Vazquez et al., 2001), the major stimulus gating TRPC3 seems to be DAG (Hofmann et al., 1999).

Although not store-operated, the TRPM2 channel in T cells has also been examined. TRMP2 is a non-selective Ca2+ channel that is activated by the intracellular secondary messengers ADP-ribose (ADPR), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and cyclic ADPR (Perraud et al., 2001; Hara et al., 2002; Massullo et al., 2006). It has been proposed that activation of T cells can increase endogenous ADPR levels in T cells which results in Ca2+ entry through TRPM2 and subsequent induction of cell death demonstrating that TRPM2 can contribute to some degree to Ca2+ signaling in T cells (Gasser et al., 2006). Recently, the TRPM2 channels have been implicated in T cell effector function. CD4+ T cells from TRPM2-deficient mice were shown to have reduced ability to proliferate and secrete cytokines following TCR activation. Furthermore, TRPM2-deficient mice had decreased inflammation and demyelinating spinal cord lesions in an EAE model (Melzer et al., 2012). Although important to T cell function, the current role of TRP receptors in Ca2+ signaling is still under investigation.

ATP-responsive purinergic P2 receptors (P2X)

The P2X receptors are ATP-gated ion channels that permit the influx of extracellular cations including Ca2+ ions (reviewed in Junger, 2011). Four family members in particular, P2X1, P2X2, P2X4, and P2X7, have been associated with T cells and may serve to amplify the TCR signal to ensure antigen recognition and T cell activation through an autocrine feedback mechanism (Bours et al., 2006; Yip et al., 2009; Woehrle et al., 2010; Junger, 2011). Upon TCR engagement, ATP is released through Pannexin 1 hemichannels that localize to the immunological synapse where they release ATP that acts on the P2X channels to promote Ca2+ influx and enhance signaling (Filippini et al., 1990; Schenk et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2009). In particular, P2X1, 4, and 7 have been shown to contribute to the increase in intracellular Ca2+, NFAT activation, proliferation, and IL-2 production in murine and human T cells following stimulation (Baricordi et al., 1996; Schenk et al., 2008; Yip et al., 2009; Woehrle et al., 2010). Initial analysis of P2X7 receptor-deficient mice revealed no major defects in T cell development (Solle et al., 2001). However, additional studies did identify a deficiency in Treg stability and function as well as Th17 differentiation (Schenk et al., 2011). Also, T cells from C57Bl/6 mice with a natural mutation in the P2X7 gene that reduces ATP sensitivity have been shown to produce reduced amounts of IL-2 following stimulation compared to Balb/c mice with a fully functional receptor further delineating a role for P2X receptors in T cell function (Adriouch et al., 2002; Yip et al., 2009). Likewise, in two models of T cell-dependent inflammation, treatment with a P2XR antagonist impeded the development of colitogenic T cells in inflammatory bowel disease and induced unresponsiveness in anti-islet TCR transgenic T cells in diabetes (Schenk et al., 2008). Therefore, it is clear that P2X channels are playing an important role in T cell Ca2+ signaling; however, the specific mechanistic details of how they fit into shaping the T cell Ca2+ environment need further exploration.

N-methyl-d-aspartate activated receptors

The NMDA receptors are a class of ligand-gated glutamate ionotropic receptors found in the central nervous system that play a crucial role in neuronal function. These receptors are heterotetramers composed of two subunits, NR1 and NR2, that form an ion channel which is highly permeable to K+, Na+, and Ca2+ (Boldyrev et al., 2012). Ca2+ entry through the receptors into the cell occurs when the NMDA receptors are activated by binding to their ligands, glutamate and glycine. In neurons, this allows for long-lasting memory formation (Boldyrev et al., 2012). Interestingly, NMDA receptors have been shown to be expressed on rodent and human T cells and contribute to the increase in intracellular Ca2+ level following T cell activation (Lombardi et al., 2001; Boldyrev et al., 2004; Miglio et al., 2005, 2007; Mashkina et al., 2007, 2010). Zainullina et al. (2011) further demonstrated that activation of T cells with thapsigargin, an inhibitor of a Ca2+-ATPase of the ER that induces Ca2+ store depletion and activation of plasma membrane Ca2+ channels, in the presence of an NMDA receptor antagonist did not affect the movement of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. However, it reduced the influx of Ca2+ from the extracellular space suggesting that NMDA receptors participate in SOCE, at least to some degree. In this scenario, the NMDA receptors may be mainly contributing to Ras/Rac-dependent signaling in T cells following TCR engagement (Zainullina et al., 2011). Analogous to neuronal synapses, a recent study of thymocytes showed that upon TCR stimulation, NMDA receptors localize to the immunological synapse (Affaticati et al., 2011). Here, DCs rapidly release glutamate that activates the NMDA receptors on the T cells contributing to the increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration. It is suggested that glutamate signaling through these receptors may participate in negative selection in the thymus by inducing apoptosis in thymocytes while it may influence proliferation in peripheral T cells (Affaticati et al., 2011). Further studies are required to determine the role glutamate plays in shaping the Ca2+ signal in T cells.

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels

CaV channels function typically in excitable cells such as nerve, muscle, and endocrine cells where they open in response to membrane depolarization to allow Ca2+ entry (Buraei and Yang, 2010). The CaV channels were initially classified based on the voltage required for activation into the subgroups high-voltage activated (HVA) and low-voltage activated (LVA) channels. Further analysis of the CaV channels allowed for additional classification of the channels into groups with distinct biophysical and pharmacological properties: T (tiny/transient)-, N (neuronal)-, P/Q (Purkinje)-, R (toxin-resistant)-, L (long-lasting)-type channels (Lacinova, 2005; Buraei and Yang, 2010).

The CaV channels are heteromultimeric protein complexes composed of five subunits: α1, α2, β, δ, and γ. The α2 and δ subunits are linked together through disulfide bonds to form a single unit referred to as α2δ. The α1 subunit of the channel is the pore-forming component responsible for the channel’s unique properties while the α2δ, β, and γ subunits regulate the structure and activity of α1 (Buraei and Yang, 2010). The α1 subunit consists of four homologous repeated motifs (I–IV) each composed of six transmembrane segments (S1–S6) with a re-entrant pore-forming loop (P-loop) between S5 and S6. The P-loop contains four highly conserved negatively charged amino acids responsible for selecting and conducting Ca2+ while the S6 segments form the inner pore (Buraei and Yang, 2010). The S4 segments are positively charged and constitute the voltage sensor. The pore opens and closes through voltage-mediated movement of this sensor (Lacinova, 2005).

Ten mammalian α1 subunits are divided into three subfamilies based on similarities in amino acid sequence. The CaV1 family contains L-type channels; the CaV2 family consists of N-, P/Q-, and R-type channels; and the CaV3 family are T-type channels (Buraei and Yang, 2010). Initially, “voltage-operable” current seemingly activated by TCR engagement or store depletion with electrophysiological properties different than the CRAC current in the plasma membrane of Jurkat T cells was identified (Densmore et al., 1992, 1996). Subsequently, numerous pharmacological and genetic studies have demonstrated the existence of CaV1 or L-type channels in T cells (Table 1). The CaV1 channels exist as four isoforms: CaV1.1, CaV1.2, CaV1.3, and CaV1.4. In excitable cells, L-type Ca2+ channels require high-voltage activation and have slow current decay kinetics. They have a unique sensitivity to 1,4-dihydropyridines (DHPs), a wide drug class that can either activate (for example: Bay K 8644) or inhibit (for example: nifedipine) the activity of the channel (Lacinova, 2005).

Table 1.

CaV1 Ca2+ channel expression in T cells.

| Subtype | Distribution | Analysis | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaV1.1 | Mouse CTLs | Protein | Matza et al. (2009) |

| Mouse effector CD8+ T cells | mRNA (PCR); protein | Jha et al. (2009) | |

| Mouse CD4+ T cells | mRNA (PCR); protein | Badou et al. (2006), Matza et al. (2008) | |

| CaV1.2 | Human peripheral blood T cells; human Jurkat, MOLT-4, CEM T cell lines | mRNA (partial sequence); protein (truncated/full) | Stokes et al. (2004) |

| Mouse CTLs | Protein | Matza et al. (2009) | |

| Mouse CD8+ T cells | mRNA (PCR) | Jha et al. (2009) | |

| Mouse CD4+ T cells | mRNA (PCR); protein | Badou et al. (2006), Matza et al. (2008) | |

| Mouse CD4+ Th2 cells | mRNA (sequence); protein | Cabral et al. (2010) | |

| Mouse BDC2.5 CD4+ T cells | mRNA (PCR) | Lee et al. (2008) | |

| CaV1.3 | Human Jurkat T cell line | mRNA (partial sequence); protein (truncated) | Stokes et al. (2004) |

| mRNA (PCR) | Colucci et al. (2009) | ||

| Mouse CD8+ T cells | mRNA (PCR) | Jha et al. (2009) | |

| Mouse CD4+ Th2 cells | mRNA (sequence); protein | Cabral et al. (2010) | |

| CaV1.4 | Human Jurkat T cell line; human spleen; human peripheral blood CD4+/CD8+ T cells | mRNA (sequence); protein | Kotturi et al. (2003), Kotturi and Jefferies (2005) |

| Human spleen and thymus; rat spleen and thymus | mRNA (PCR); protein | McRory et al. (2004) | |

| Mouse T cells | mRNA (PCR); protein (truncated) | Omilusik et al. (2011) | |

| Mouse naïve CD8+ T cells | mRNA (PCR); protein | Jha et al. (2009) | |

| Mouse CD4+ T cells | mRNA (PCR) | Badou et al. (2006), Colucci et al. (2009) |

Early studies suggesting that L-type Ca2+ channels contributed to T cell Ca2+ signaling relied on pharmaceutical analysis (Grafton and Thwaite, 2001; Kotturi et al., 2003; Gomes et al., 2004). These include in vitro experiments where the DHP antagonist nifedipine was shown to block proliferation of human T cells or peripheral blood mononuclear cells or impair increase in intracellular Ca2+following stimulation with mitogens (Birx et al., 1984; Gelfand et al., 1986; Dupuis et al., 1993). This effect of nifedipine seemed to be dose-dependent when T cells were stimulated in the presence of the immunosuppressive agent cyclosporine A (Marx et al., 1990; Padberg et al., 1990). In a resultant study performed by Kotturi et al. (2003), treatment of Jurkat T cells and human peripheral blood T cells with the DHP agonist Bay K 8644 was shown to increase intracellular Ca2+ levels and induce ERK 1/2 phosphorylation, while treatment with the DHP antagonist nifedipine blocked Ca2+ influx, ERK 1/2 phosphorylation, NFAT activation, IL-2 production, and T cell proliferation. At micromolar concentrations, DHPs can also affect the function of K+ channels and therefore conclusions drawn from these pharmaceutical studies (Grafton and Thwaite, 2001; Kotturi et al., 2003, 2006; Gomes et al., 2004) regarding contribution of CaV1 to T cell function have been criticized (Wulff et al., 2003, 2004). However, inhibitory effects have been noted when DHP antagonists were used at concentrations well below those influencing K+ channels (Sadighi Akha et al., 1996; Kotturi et al., 2003) as well as with the more specific CaV1 blocker, calciseptine, that also obstructs Ca2+ influx in T cells (de Weille et al., 1991; Matza and Flavell, 2009).

Subsequent genetic studies have confirmed the expression of L-type Ca2+ channels in T cells and have gone on to compare their structure to those found in excitable cells. CaV1.4 was the first CaV1 channel identified in T cells (Kotturi et al., 2003; Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005; Omilusik et al., 2011). The CaV1.4 α1 subunit is encoded by the CACNA1F gene originally cloned from human retina (Fisher et al., 1997) where CaV1.4 mediates Ca2+ entry into the photoreceptors promoting tonic neurotransmitter release (Strom et al., 1998). Kotturi et al. identified the CaV1.4α1 subunit mRNA and protein in Jurkat T cells as well as in human peripheral blood T cells (Kotturi et al., 2003; Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005). This human lymphocyte form of Cav1.4 was shown to undergo alternative splicing, resulting in a protein smaller in size compared to a retinoblastoma version (Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005). Sequence analysis revealed that the CaV1.4 expressed in human T cells exists as two novel splice variants (termed CaV1.4a and CaV1.4b) distinct from the retina (Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005). CaV1.4a lacks exons 31, 32, 33, 34, and 37 resulting in deletions of transmembrane segments S3, S4, S5, and half of S6 in motif IV. As a result, the voltage sensor domain and part of the DHP binding site and EF-hand Ca2+ binding motif are deleted from the channel. While the removal of the voltage sensor may alter the voltage-gated activation of this channel, partial deletion of the DHP binding site may decrease the sensitivity of T cell-specific CaV1.4 channels. This explained why large doses of DHP antagonists are required to completely block Ca2+ influx through CaV channels in T cells (Dupuis et al., 1993). Remarkably, the splice event caused a frameshift that changed the carboxy-terminus to a sequence that resembles (40% identity) the CaV1.1 channel found in skeletal muscle (Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005). The second splice variant, CaV1.4b, lacks exons 32 and 36 causing a deletion of the extracellular loop between S3 and S4 in motif IV. CaV1.4b also has an early stop codon that prematurely truncates the channel. The voltage sensing motif is not spliced out; however, it has been proposed that removal of the extracellular loop may alter the voltage sensing function of this channel (Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005). Upon membrane depolarization, the S4 voltage sensor domain moves and this splicing event may leave the domain in a conformation that prevents S4 movement (Bezanilla, 2002; Jurkat-Rott and Lehmann-Horn, 2004). Since their discovery in T cells (Kotturi and Jefferies, 2005), alternative splice variants of other CaV channels have been found. Analogous structural changes have been subsequently noted for CaV1.1 (Matza and Flavell, 2009) with one isoform similarly lacking the extracellular loop between S3 and S4 in motif IV that translated to shifted voltage sensitivity in muscle cells (Tuluc et al., 2009). These structural changes likely explain the insensitivity of T cell CaV1 channels to be activated by cell depolarization and instead, gating in T cells may be through alternate mechanisms such as ER store-depletion or TCR signaling. Supporting this hypothesis, Jha et al. (2009) recently found CaV1.4 to be localized to lipid rafts in the plasma membrane of murine T cells. CaV1.4 was found to be associated with components of the T cell signaling complex. Given its location, CaV1 channel activity could be regulated in T cells by downstream TCR signaling events.

Recent in vivo studies have directly addressed the controversy regarding the importance of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in T cell function. Mice with targeted deletions in the regulatory β subunits that mediate CaV channel assembly, plasma membrane targeting, and activation have been described (Badou et al., 2006; Buraei and Yang, 2010). The β3 and β4 family members are expressed in naïve CD4+ T cells and upregulated in activated T cells. Upon TCR cross-linking, CD4+ T cells from β3 or β4-deficient mice showed impaired Ca2+ influx, NFAT nuclear translocation, and cytokine secretion (Badou et al., 2006). Cav1.1 expression was found to be reduced in the β4-deficient T cells providing a possible role for CaV1 in lymphocyte function (Badou et al., 2006). The same group later examined CD8+ T cell populations in a β3-deficient mouse (Jha et al., 2009). β3−/− mice have reduced numbers of CD8+ T cells possibly due to increased spontaneous apoptosis induced by higher expression of Fas. Upon activation, these CD8+ T cells have decreased Ca2+ entry, proliferation, and NFAT nuclear translocation. β3 was found to associate with CaV1.4 and several TCR signaling proteins suggesting its role in TCR gated Ca2+ signaling (Jha et al., 2009). Similarly, when the AHNAK1 protein, a large scaffold protein required for CaV1.1 surface expression, was disrupted, T cells had reduced Ca2+ influx and NFAT activation that equated to poor effector function (Matza et al., 2008, 2009). Recently, Cabral et al. (2010) began to address differential Ca2+ signaling in T cell subsets. This study demonstrated that CaV1.2 and CaV1.3 channels were expressed in Th2 but not Th1 differentiated effector T cells. Knockdown of CaV1.2 and/or CaV1.3 expression in Th2 cells with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides resulted in reduced Ca2+ influx following TCR stimulation and impaired cytokine secretion (Cabral et al., 2010). In addition, Th2 cells with disrupted CaV1 expression were impaired in their ability to induce asthma in an adoptive transfer model (Cabral et al., 2010). Further studies defining the Cav1 channel subtype or splice variant essential to various stages of development and activation of the T cell subsets will likely provide an explanation for differences in Ca2+ responses.

Omilusik et al. (2011) used a murine model deficient for CaV1.4 (Mansergh et al., 2005), one of the pore-forming subunits of a CaV channel, to unequivocally establish a T cell-intrinsic role for CaV1s in the activation, survival, and maintenance of naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vivo. CaV1.4 was shown to be essential for TCR-induced regulation of cytosolic free Ca2+ and downstream TCR signaling, impacting activation of the Ras/ERK and NFAT pathways, IL-7 receptor expression and IL-7 responsiveness. The loss of CaV1.4 and subsequently naïve peripheral T cells resulted in deficient immune responses when challenged with the model bacteria, L. monocytogenes. Instead of being activated by Ca2+ store release as in the case of ORAI1, it appears that CaV1.4 may operate to create intracellular Ca2+ stores in the ER. Low-level TCR signaling through interactions with self-antigens (i.e., self-peptides/self-MHC molecules) may result in CaV1.4-mediated Ca2+ influx from outside the cell, allowing the filling of intracellular stores and the initiation of a pro-survival program. This recent data supports the concept that in the absence of CaV1.4, there is a reduction in the influx of extracellular Ca2+ coupled to self/MHC-TCR interaction, resulting in low cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels and depleted Ca2+ ER stores (Omilusik et al., 2011). Therefore, when CaV1.4-deficient T cells are stimulated through the TCR, there is a defective Ca2+ release from the ER as a result of lower levels of stored Ca2+, decreased subsequent SOCE, and diminished inward Ca2+ flux through CRAC channels leading to weakened Ca2+-dependent signaling. Overall, the absence of tonic survival signals provided by CaV1.4 results in failure of naïve T cells to thrive and perpetuates a state of immunological activation and exhaustion (Omilusik et al., 2011). Studies on other immune cells support this contention. For example, CaV1.2 expressed in mast cells has been reported to protect against antigen-induced cell death by maintaining mitochondria integrity and inhibiting the mitochondrial cell death pathway (Suzuki et al., 2009). Using pharmacological agents and siRNA specific knockdown, Suzuki et al. (2009) demonstrated that CaV1.2 channels protect mast cells from undergoing apoptosis following FcεRI activation as discerned by assessing mitochondrial membrane potential, cytochrome c release, and caspase-3/7 activation. Furthermore, though it remains unclear, it appears that Ca2+ influx through CaV1.2 at the plasma membrane may be important for maintenance of the mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration, thereby providing the cell with pro-survival signals (Suzuki et al., 2009). In conclusion, it is of importance to note that knock-outs of the components of CaV1 channels in T cells have, by large, more severe phenotypes than those of other categories of Ca2+ channels in T cells and, certainly, this argues strongly that CaV1 channels play a significant role in regulating and orchestrating T cell biology.

It is interesting to consider and likely profoundly important for integrating the multiple functions of T cells with other homeostatic processes, that CaV1 coexist in excitable and non-excitable cells with other Ca2+ channels and the interplay between the channels all likely contribute to the highly regulated Ca2+ signaling system. CaV1 channels have been shown to interact with the ER/sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) ryanodine receptors (RyRs) in excitable cells (Lanner et al., 2010). In skeletal muscle, CaV1.1 channels are activated by membrane depolarization and through a physical interaction with RyR1 stimulate the release of Ca2+ from the SR. Similarly, in cardiac muscle, CaV1.2 is triggered to mediate entry of extracellular Ca2+ which in turn activates RyR2 channels to release intracellular Ca2+ stores (Lanner et al., 2010). Both mechanisms have also been observed in neurons (Chavis et al., 1996; Mouton et al., 2001). Although T cells express RyRs (Hosoi et al., 2001) and these receptors have been shown to contribute to Ca2+ signaling following TCR activation (Hohenegger et al., 1999; Schwarzmann et al., 2002; Conrad et al., 2004), further studies are needed to demonstrate a CaV1–RyR interaction.

An interplay between voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSC) and CaV1 has also been suggested to shape the T cell Ca2+ signal. In excitable cells such as muscle and neurons, membrane depolarization by VGSC leads to an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ through the activation of CaV channels (Dravid et al., 2004; Fekete et al., 2009; Catterall, 2010). A recent study in T cells has determined an essential role for a VGSC in positive selection (Lo et al., 2012). Pharmacological inhibition and shRNA-mediated knockdown was used to demonstrate that the VGSC composed of a pore-forming SCN5a and a regulatory SCN5b subunit is necessary for Ca2+ influx during positive selection of CD4+ T cells. It is proposed that this SCN5a-SCN5b channel is expressed in double positive T cells in order to convert a weak positive selection signal into a sustained Ca2+ flux necessary for positive selection to take place. However, once in the periphery, T cells no longer express the channel to eliminate the possibility of autoimmunity (Lo et al., 2012). ORAI1 and STIM1 do not seem to contribute to thymic development of conventional TCRαβ T cells (Oh-Hora et al., 2013); therefore, it is an interesting idea that VGSC activation by kinases downstream of the TCR (Rook et al., 2012) can induce Ca2+ signaling by CaV1 in developing T cells. Further studies are required to formally demonstrate a functional link between CaV1 and VGSC channels in lymphocytes.

Recently, an interesting reciprocal relationship between CaV1.2 and ORAI1 has been described (Park et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010). After Ca2+ store depletion in the ER, STIM1 oligomers form at ER-plasma membrane junctions allowing the STIM1 CRAC-activating domain (CAD) to interact with the C-terminus of ORAI1 and CaV1.2 channels. ORAI1 channels are activated by STIM1 and subsequently open causing sustained Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space. Conversely, STIM1 inhibits Ca2+ influx through CaV1.2 and promotes its internalization, further shutting down the activity of the channel (Park et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010). It is interesting to speculate that strong TCR signaling through engagement by a foreign peptide-MHC may trigger this activation of ORAI1 and inhibition of CaV1 channels (Figure 1). However, low-level TCR signaling through interactions with self-antigens (i.e., self-peptides/self-MHC molecules) may not induce STIM1 to localize to the plasma membrane thereby activating CaV and co-ordinately inhibiting ORAI1. This results in CaV1-mediated Ca2+ influx from outside the cell, filling of depleted intracellular stores, and induction of a signaling cascade to activate a pro-survival program within the naïve T cell. The activation and inhibition of CaV1 channels through STIM1 or other TCR-mediated events is an intriguing concept and will likely be the focus of many new studies.

Although CaV1 function is vital for T cell Ca2+ signaling, their specific functions have yet to be fully explored. Further work is required to clarify the role played by each CaV1 channel family member as well as the other Ca2+ channels in shaping the Ca2+ signal. Altogether, these studies do provide a new framework for understanding the regulation of lymphocyte biology through the function of several Ca2+ channels, particularly the L-type Ca2+ channels, in the storage of intracellular Ca2+ and operative Ca2+ regulation during antigen receptor-mediated signal transduction.

Overall, the translational aspects of the current research in the field of Ca2+ channel biology have direct implications in designing new modalities for modifying T cell responses using drugs that are known to control Ca2+ channels activities, such as the plethora of drugs that already exist for modifying CaV1 channels. Agents that target the CaV1 splice variants expressed in lymphocytes and inhibit the activity of the channel may serve as more specific immunosuppressants than the current options. Relevant applications for these agents may include therapy for autoimmune diseases, reduction of transplant rejection risk, and treatment of other disorders requiring suppression or in the case of existing immunodeficiency, activation of the immune system.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Adriouch S., Dox C., Welge V., Seman M., Koch-Nolte F., Haag F. (2002). Cutting edge: a natural P451L mutation in the cytoplasmic domain impairs the function of the mouse P2X7 receptor. J. Immunol. 169, 4108–4112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affaticati P., Mignen O., Jambou F., Potier M. C., Klingel-Schmitt I., Degrouard J., et al. (2011). Sustained calcium signalling and caspase-3 activation involve NMDA receptors in thymocytes in contact with dendritic cells. Cell Death Differ. 18, 99–108 10.1038/cdd.2010.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badou A., Jha M. K., Matza D., Mehal W. Z., Freichel M., Flockerzi V., et al. (2006). Critical role for the beta regulatory subunits of Cav channels in T lymphocyte function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15529–15534 10.1073/pnas.0607262103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baricordi O. R., Ferrari D., Melchiorri L., Chiozzi P., Hanau S., Chiari E., et al. (1996). An ATP-activated channel is involved in mitogenic stimulation of human T lymphocytes. Blood 87, 682–690 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge M. J. (1993). Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature 361, 315–325 10.1038/361315a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F. (2002). Voltage sensor movements. J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 465–473 10.1085/jgp.20028660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birx D. L., Berger M., Fleisher T. A. (1984). The interference of T cell activation by calcium channel blocking agents. J. Immunol. 133, 2904–2909 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodding M., Wissenbach U., Flockerzi V. (2002). The recombinant human TRPV6 channel functions as Ca2+ sensor in human embryonic kidney and rat basophilic leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36656–36664 10.1074/jbc.M202822200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldyrev A. A., Bryushkova E. A., Vladychenskaya E. A. (2012). NMDA receptors in immune competent cells. Biochemistry Mosc. 77, 128–134 10.1134/S0006297912020022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldyrev A. A., Kazey V. I., Leinsoo T. A., Mashkina A. P., Tyulina O. V., Johnson P., et al. (2004). Rodent lymphocytes express functionally active glutamate receptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 133–139 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bours M. J., Swennen E. L., Di Virgilio F., Cronstein B. N., Dagnelie P. C. (2006). Adenosine 5’-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol. Ther. 112, 358–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandman O., Liou J., Park W. S., Meyer T. (2007). STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell 131, 1327–1339 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z., Yang J. (2010). The ss subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol. Rev. 90, 1461–1506 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral M. D., Paulet P. E., Robert V., Gomes B., Renoud M. L., Savignac M., et al. (2010). Knocking down Cav1 calcium channels implicated in Th2 cell activation prevents experimental asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181, 1310–1317 10.1164/rccm.200907-1166OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall W. A. (2010). Signaling complexes of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Neurosci. Lett. 486, 107–116 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.08.085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis P., Fagni L., Lansman J. B., Bockaert J. (1996). Functional coupling between ryanodine receptors and L-type calcium channels in neurons. Nature 382, 719–722 10.1038/382719a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham D. E., Montell C., Schultz G., Julius D. (2003). International Union of Pharmacology. XLIII. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: transient receptor potential channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 55, 591–596 10.1124/pr.55.4.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci A., Giunti R., Senesi S., Bygrave F. L., Benedetti A., Gamberucci A. (2009). Effect of nifedipine on capacitive calcium entry in Jurkat T lymphocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 481, 80–85 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad D. M., Hanniman E. A., Watson C. L., Mader J. S., Hoskin D. W. (2004). Ryanodine receptor signaling is required for anti-CD3-induced T cell proliferation, interleukin-2 synthesis, and interleukin-2 receptor signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 92, 387–399 10.1002/jcb.20064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Bian J. S., Kagan A., McDonald T. V. (2002). CaT1 contributes to the stores-operated calcium current in Jurkat T-lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47175–47183 10.1074/jbc.M205870200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen P. J., Lockyer P. J. (2002). Integration of calcium and Ras signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 339–348 10.1038/nrm808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weille J. R., Schweitz H., Maes P., Tartar A., Lazdunski M. (1991). Calciseptine, a peptide isolated from black mamba venom, is a specific blocker of the L-type calcium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 2437–2440 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Boyles R. R., Putney J. W., Jr. (2007). Calcium inhibition and calcium potentiation of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 calcium release-activated calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 17548–17556 10.1074/jbc.M611374200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Densmore J. J., Haverstick D. M., Szabo G., Gray L. S. (1996). A voltage-operable current is involved in Ca2+ entry in human lymphocytes whereas ICRAC has no apparent role. Am. J. Physiol. 271, C1494–C1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Densmore J. J., Szabo G., Gray L. S. (1992). A voltage-gated calcium channel is linked to the antigen receptor in Jurkat T lymphocytes. FEBS Lett. 312, 161–164 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80926-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dravid S. M., Baden D. G., Murray T. F. (2004). Brevetoxin activation of voltage-gated sodium channels regulates Ca dynamics and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in murine neocortical neurons. J. Neurochem. 89, 739–749 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02407.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis G., Aoudjit F., Ricard I., Payet M. D. (1993). Effects of modulators of cytosolic Ca2+ on phytohemagglutin-dependent Ca2+ response and interleukin-2 production in Jurkat cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 53, 66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanger C. M., Hoth M., Crabtree G. R., Lewis R. S. (1995). Characterization of T cell mutants with defects in capacitative calcium entry: genetic evidence for the physiological roles of CRAC channels. J. Cell Biol. 131, 655–667 10.1083/jcb.131.3.655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanger C. M., Neben A. L., Cahalan M. D. (2000). Differential Ca2+ influx, KCa channel activity, and Ca2+ clearance distinguish Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 164, 1153–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete A., Franklin L., Ikemoto T., Rozsa B., Lendvai B., Sylvester Vizi E., et al. (2009). Mechanism of the persistent sodium current activator veratridine-evoked Ca elevation: implication for epilepsy. J. Neurochem. 111, 745–756 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S. (2009). ORAI1 and STIM1 deficiency in human and mice: roles of store-operated Ca2+ entry in the immune system and beyond. Immunol. Rev. 231, 189–209 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00818.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Giltnane J., Dolmetsch R., Staudt L. M., Rao A. (2001). Gene regulation mediated by calcium signals in T lymphocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2, 316–324 10.1038/86318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S. H., Tanasa B., et al. (2006). A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 441, 179–185 10.1038/nature04702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Prakriya M., Rao A., Lewis R. S. (2005). A severe defect in CRAC Ca2+ channel activation and altered K+ channel gating in T cells from immunodeficient patients. J. Exp. Med. 202, 651–662 10.1084/jem.20050687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S., Skolnik E. Y., Prakriya M. (2012). Ion channels and transporters in lymphocyte function and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 532–547 10.1038/nri3233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini A., Taffs R. E., Sitkovsky M. V. (1990). Extracellular ATP in T-lymphocyte activation: possible role in effector functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 8267–8271 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S. E., Ciccodicola A., Tanaka K., Curci A., Desicato S., D’urso M., et al. (1997). Sequence-based exon prediction around the synaptophysin locus reveals a gene-rich area containing novel genes in human proximal Xp. Genomics 45, 340–347 10.1006/geno.1997.4941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser A., Glassmeier G., Fliegert R., Langhorst M. F., Meinke S., Hein D., et al. (2006). Activation of T cell calcium influx by the second messenger ADP-ribose. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2489–2496 10.1074/jbc.M506525200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand E. W., Cheung R. K., Grinstein S., Mills G. B. (1986). Characterization of the role for calcium influx in mitogen-induced triggering of human T cells. Identification of calcium-dependent and calcium-independent signals. Eur. J. Immunol. 16, 907–912 10.1002/eji.1830160806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes B., Savignac M., Moreau M., Leclerc C., Lory P., Guery J. C., et al. (2004). Lymphocyte calcium signaling involves dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type calcium channels: facts and controversies. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 24, 425–447 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v24.i6.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafton G., Thwaite L. (2001). Calcium channels in lymphocytes. Immunology 104, 119–126 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01321.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Oh-Hora M., Hogan P. G., Lamperti E. D., Yamashita M., et al. (2008). Hair loss and defective T- and B-cell function in mice lacking ORAI1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 5209–5222 10.1128/MCB.00360-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y., Wakamori M., Ishii M., Maeno E., Nishida M., Yoshida T., et al. (2002). LTRPC2 Ca2+-permeable channel activated by changes in redox status confers susceptibility to cell death. Mol. Cell 9, 163–173 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00438-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L. P., Hewavitharana T., Soboloff J., Spassova M. A., Gill D. L. (2005). A functional link between store-operated and TRPC channels revealed by the 3,5-bis-trifluoromethyl-pyrazole derivative, BTP2. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10997–11006 10.1074/jbc.M411797200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T., Obukhov A. G., Schaefer M., Harteneck C., Gudermann T., Schultz G. (1999). Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature 397, 259–263 10.1038/16711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan P. G., Chen L., Nardone J., Rao A. (2003). Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 17, 2205–2232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Rao A. (2010). Molecular basis of calcium signaling in lymphocytes: STIM and ORAI. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 491–533 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohenegger M., Berg I., Weigl L., Mayr G. W., Potter B. V., Guse A. H. (1999). Pharmacological activation of the ryanodine receptor in Jurkat T-lymphocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 128, 1235–1240 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi E., Nishizaki C., Gallagher K. L., Wyre H. W., Matsuo Y., Sei Y. (2001). Expression of the ryanodine receptor isoforms in immune cells. J. Immunol. 167, 4887–4894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha M. K., Badou A., Meissner M., McRory J. E., Freichel M., Flockerzi V., et al. (2009). Defective survival of naive CD8+ T lymphocytes in the absence of the beta3 regulatory subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels. Nat. Immunol. 10, 1275–1282 10.1038/ni.1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger W. G. (2011). Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 201–212 10.1038/nri2938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkat-Rott K., Lehmann-Horn F. (2004). The impact of splice isoforms on voltage-gated calcium channel alpha1 subunits. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 554, 609–619 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A. A., Steiner J. P., Klein M. G., Schneider M. F., Snyder S. H. (1992). IP3 receptor: localization to plasma membrane of T cells and cocapping with the T cell receptor. Science 257, 815–818 10.1126/science.1323146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotturi M. F., Carlow D. A., Lee J. C., Ziltener H. J., Jefferies W. A. (2003). Identification and functional characterization of voltage-dependent calcium channels in T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46949–46960 10.1074/jbc.M309268200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotturi M. F., Hunt S. V., Jefferies W. A. (2006). Roles of CRAC and Cav-like channels in T cells: more than one gatekeeper? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 360–367 10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotturi M. F., Jefferies W. A. (2005). Molecular characterization of L-type calcium channel splice variants expressed in human T lymphocytes. Mol. Immunol. 42, 1461–1474 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacinova L. (2005). Voltage-dependent calcium channels. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 24(Suppl. 1), 1–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanner J. T., Georgiou D. K., Joshi A. D., Hamilton S. L. (2010). Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a003996 10.1101/cshperspect.a003996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Deist F., Hivroz C., Partiseti M., Thomas C., Buc H. A., Oleastro M., et al. (1995). A primary T-cell immunodeficiency associated with defective transmembrane calcium influx. Blood 85, 1053–1062 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L. F., Lih C. J., Huang C. J., Cao T., Cohen S. N., McDevitt H. O. (2008). Genomic expression profiling of TNF-alpha-treated BDC2.5 diabetogenic CD4+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10107–10112 10.1073/pnas.0803336105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J., Fivaz M., Inoue T., Meyer T. (2007). Live-cell imaging reveals sequential oligomerization and local plasma membrane targeting of stromal interaction molecule 1 after Ca2+ store depletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9301–9306 10.1073/pnas.0702866104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J., Kim M. L., Heo W. D., Jones J. T., Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E., Jr., et al. (2005). STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 15, 1235–1241 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis A., Peinelt C., Beck A., Parvez S., Monteilh-Zoller M., Fleig A., et al. (2007). CRACM1, CRACM2, and CRACM3 are store-operated Ca2+ channels with distinct functional properties. Curr. Biol. 17, 794–800 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo W. L., Donermeyer D. L., Allen P. M. (2012). A voltage-gated sodium channel is essential for the positive selection of CD4(+) T cells. Nat. Immunol. 13, 880–887 10.1038/ni.2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi G., Dianzani C., Miglio G., Canonico P. L., Fantozzi R. (2001). Characterization of ionotropic glutamate receptors in human lymphocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 133, 936–944 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luik R. M., Wu M. M., Buchanan J., Lewis R. S. (2006). The elementary unit of store-operated Ca2+ entry: local activation of CRAC channels by STIM1 at ER-plasma membrane junctions. J. Cell Biol. 174, 815–825 10.1083/jcb.200604015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macian F. (2005). NFAT proteins: key regulators of T-cell development and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 472–484 10.1038/nri1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh F., Orton N. C., Vessey J. P., Lalonde M. R., Stell W. K., Tremblay F., et al. (2005). Mutation of the calcium channel gene Cacna1f disrupts calcium signaling, synaptic transmission and cellular organization in mouse retina. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 3035–3046 10.1093/hmg/ddi336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx M., Weber M., Merkel F., Meyer Zum Buschenfelde K. H., Kohler H. (1990). Additive effects of calcium antagonists on cyclosporin A-induced inhibition of T-cell proliferation. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 5, 1038–1044 10.1093/ndt/5.12.1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashkina A. P., Cizkova D., Vanicky I., Boldyrev A. A. (2010). NMDA receptors are expressed in lymphocytes activated both in vitro and in vivo. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 30, 901–907 10.1007/s10571-010-9519-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashkina A. P., Tyulina O. V., Solovyova T. I., Kovalenko E. I., Kanevski L. M., Johnson P., et al. (2007). The excitotoxic effect of NMDA on human lymphocyte immune function. Neurochem. Int. 51, 356–360 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massullo P., Sumoza-Toledo A., Bhagat H., Partida-Sanchez S. (2006). TRPM channels, calcium and redox sensors during innate immune responses. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 654–666 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matza D., Badou A., Jha M. K., Willinger T., Antov A., Sanjabi S., et al. (2009). Requirement for AHNAK1-mediated calcium signaling during T lymphocyte cytolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 9785–9790 10.1073/pnas.0902844106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matza D., Badou A., Kobayashi K. S., Goldsmith-Pestana K., Masuda Y., Komuro A., et al. (2008). A scaffold protein, AHNAK1, is required for calcium signaling during T cell activation. Immunity 28, 64–74 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matza D., Flavell R. A. (2009). Roles of Ca(v) channels and AHNAK1 in T cells: the beauty and the beast. Immunol. Rev. 231, 257–264 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00805.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRory J. E., Hamid J., Doering C. J., Garcia E., Parker R., Hamming K., et al. (2004). The CACNA1F gene encodes an L-type calcium channel with unique biophysical properties and tissue distribution. J. Neurosci. 24, 1707–1718 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4846-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer N., Hicking G., Gobel K., Wiendl H. (2012). TRPM2 cation channels modulate T cell effector functions and contribute to autoimmune CNS inflammation. PLoS ONE 7:e47617 10.1371/journal.pone.0047617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miglio G., Dianzani C., Fallarini S., Fantozzi R., Lombardi G. (2007). Stimulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors modulates Jurkat T cell growth and adhesion to fibronectin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361, 404–409 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miglio G., Varsaldi F., Lombardi G. (2005). Human T lymphocytes express N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors functionally active in controlling T cell activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 1875–1883 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignen O., Thompson J. L., Shuttleworth T. J. (2007). STIM1 regulates Ca2+ entry via arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels without store depletion or translocation to the plasma membrane. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 579, 703–715 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignen O., Thompson J. L., Shuttleworth T. J. (2009). The molecular architecture of the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective ARC channel is a pentameric assembly of Orai1 and Orai3 subunits. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 587, 4181–4197 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C., Rubin G. M. (1989). Molecular characterization of the Drosophila trp locus: a putative integral membrane protein required for phototransduction. Neuron 2, 1313–1323 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90069-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton J., Marty I., Villaz M., Feltz A., Maulet Y. (2001). Molecular interaction of dihydropyridine receptors with type-1 ryanodine receptors in rat brain. Biochem. J. 354, 597–603 10.1042/0264-6021:3540597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh-Hora M. (2009). Calcium signaling in the development and function of T-lineage cells. Immunol. Rev. 231, 210–224 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00819.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh-Hora M., Komatsu N., Pishyareh M., Feske S., Hori S., Taniguchi M., et al. (2013). Agonist-selected T cell development requires strong T cell receptor signaling and store-operated calcium entry. Immunity 38, 881–895 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh-Hora M., Yamashita M., Hogan P. G., Sharma S., Lamperti E., Chung W., et al. (2008). Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 9, 432–443 10.1038/ni1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omilusik K., Priatel J. J., Chen X., Wang Y. T., Xu H., Choi K. B., et al. (2011). The CaV1.4 calcium channel is a critical regulator of T cell receptor signaling and naive T cell homeostasis. Immunity 35, 349–360 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owsianik G., Talavera K., Voets T., Nilius B. (2006). Permeation and selectivity of TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 68, 685–717 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.101406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padberg W. M., Bodewig C., Schafer H., Muhrer K. H., Schwemmle K. (1990). Synergistic immunosuppressive effect of low-dose cyclosporine A and the calcium antagonist nifedipine, mediated by the generation of suppressor cells. Transplant. Proc. 22, 2337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. Y., Hoover P. J., Mullins F. M., Bachhawat P., Covington E. D., Raunser S., et al. (2009). STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell 136, 876–890 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. Y., Shcheglovitov A., Dolmetsch R. (2010). The CRAC channel activator STIM1 binds and inhibits L-type voltage-gated calcium channels. Science 330, 101–105 10.1126/science.1191027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partiseti M., Le Deist F., Hivroz C., Fischer A., Korn H., Choquet D. (1994). The calcium current activated by T cell receptor and store depletion in human lymphocytes is absent in a primary immunodeficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 32327–32335 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson R. L., Boehning D., Snyder S. H. (2004). Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors as signal integrators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 437–465 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.071403.161303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penna A., Demuro A., Yeromin A. V., Zhang S. L., Safrina O., Parker I., et al. (2008). The CRAC channel consists of a tetramer formed by Stim-induced dimerization of Orai dimers. Nature 456, 116–120 10.1038/nature07338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perraud A. L., Fleig A., Dunn C. A., Bagley L. A., Launay P., Schmitz C., et al. (2001). ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature 411, 595–599 10.1038/35079100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp S., Strauss B., Hirnet D., Wissenbach U., Mery L., Flockerzi V., et al. (2003). TRPC3 mediates T-cell receptor-dependent calcium entry in human T-lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26629–26638 10.1074/jbc.M304044200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard C., McCarl C. A., Papolos A., Khalil S., Luthy K., Hivroz C., et al. (2009). STIM1 mutation associated with a syndrome of immunodeficiency and autoimmunity. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1971–1980 10.1056/NEJMoa0900082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert V., Triffaux E., Savignac M., Pelletier L. (2011). Calcium signalling in T-lymphocytes. Biochimie 93, 2087–2094 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook M. B., Evers M. M., Vos M. A., Bierhuizen M. F. (2012). Biology of cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 expression. Cardiovasc. Res. 93, 12–23 10.1093/cvr/cvr252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J., Digregorio P. J., Yeromin A. V., Ohlsen K., Lioudyno M., Zhang S., et al. (2005). STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J. Cell Biol. 169, 435–445 10.1083/jcb.200502019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadighi Akha A. A., Willmott N. J., Brickley K., Dolphin A. C., Galione A., Hunt S. V. (1996). Anti-Ig-induced calcium influx in rat B lymphocytes mediated by cGMP through a dihydropyridine-sensitive channel. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 7297–7300 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk U., Frascoli M., Proietti M., Geffers R., Traggiai E., Buer J., et al. (2011). ATP inhibits the generation and function of regulatory T cells through the activation of purinergic P2X receptors. Sci. Signal. 4, ra12 10.1126/scisignal.2001270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk U., Westendorf A. M., Radaelli E., Casati A., Ferro M., Fumagalli M., et al. (2008). Purinergic control of T cell activation by ATP released through pannexin-1 hemichannels. Sci. Signal. 1, ra6 10.1126/scisignal.1160583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann M. K., Stegner D., Berna-Erro A., Bittner S., Braun A., Kleinschnitz C., et al. (2010). Stromal interaction molecules 1 and 2 are key regulators of autoreactive T cell activation in murine autoimmune central nervous system inflammation. J. Immunol. 184, 1536–1542 10.4049/jimmunol.0902161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz E. C., Wissenbach U., Niemeyer B. A., Strauss B., Philipp S. E., Flockerzi V., et al. (2006). TRPV6 potentiates calcium-dependent cell proliferation. Cell Calcium 39, 163–173 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz E. C., Wolfs M. J., Tonner S., Wenning A. S., Quintana A., Griesemer D., et al. (2007). TRP channels in lymphocytes. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 179, 445–456 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzmann N., Kunerth S., Weber K., Mayr G. W., Guse A. H. (2002). Knock-down of the type 3 ryanodine receptor impairs sustained Ca2+ signaling via the T cell receptor/CD3 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50636–50642 10.1074/jbc.M209061200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Garvin J. E., Koretzky G. A., Jordan M. S. (2009). T cell activation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 591–619 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soboloff J., Spassova M. A., Hewavitharana T., He L. P., Xu W., Johnstone L. S., et al. (2006). STIM2 is an inhibitor of STIM1-mediated store-operated Ca2+ Entry. Curr. Biol. 16, 1465–1470 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solle M., Labasi J., Perregaux D. G., Stam E., Petrushova N., Koller B. H., et al. (2001). Altered cytokine production in mice lacking P2X(7) receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 125–132 10.1074/jbc.M006781200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth S., Gwack Y. (2012). Orai1, STIM1, and their associating partners. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 590, 4169–4177 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.231522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopulos P. B., Zheng L., Ikura M. (2009). Stromal interaction molecule (STIM) 1 and STIM2 calcium sensing regions exhibit distinct unfolding and oligomerization kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 728–732 10.1074/jbc.C800178200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes L., Gordon J., Grafton G. (2004). Non-voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels in human T cells: pharmacology and molecular characterization of the major alpha pore-forming and auxiliary beta-subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19566–19573 10.1074/jbc.M401481200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom T. M., Nyakatura G., Apfelstedt-Sylla E., Hellebrand H., Lorenz B., Weber B. H., et al. (1998). An L-type calcium-channel gene mutated in incomplete X-linked congenital stationary night blindness. Nat. Genet. 19, 260–263 10.1038/940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y., Yoshimaru T., Inoue T., Ra C. (2009). Ca(v)1.2 L-type Ca2+ channel protects mast cells against activation-induced cell death by preventing mitochondrial integrity disruption. Mol. Immunol. 46, 2370–2380 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimura A., Tojyo Y., Turner R. J. (2000). Evidence that type I, II, and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors can occur as integral plasma membrane proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27488–27493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeiro E., Daniels M. A. (2010). ERK and cell death: ERK location and T cell selection. FEBS J. 277, 30–38 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tone Y., Furuuchi K., Kojima Y., Tykocinski M. L., Greene M. I., Tone M. (2008). Smad3 and NFAT cooperate to induce Foxp3 expression through its enhancer. Nat. Immunol. 9, 194–202 10.1038/ni1549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuluc P., Molenda N., Schlick B., Obermair G. J., Flucher B. E., Jurkat-Rott K. (2009). A CaV1.1 Ca2+ channel splice variant with high conductance and voltage-sensitivity alters EC coupling in developing skeletal muscle. Biophys. J. 96, 35–44 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez G., Lievremont J. P., St J. B. G., Putney J. W., Jr. (2001). Human Trp3 forms both inositol trisphosphate receptor-dependent and receptor-independent store-operated cation channels in DT40 avian B lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 11777–11782 10.1073/pnas.201238198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M., Dehaven W. I., Bird G. S., Billingsley J. M., Wang H., Rao P. E., et al. (2008). Defective mast cell effector functions in mice lacking the CRACM1 pore subunit of store-operated calcium release-activated calcium channels. Nat. Immunol. 9, 89–96 10.1038/nrg2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M., Peinelt C., Beck A., Koomoa D. L., Rabah D., Koblan-Huberson M., et al. (2006). CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science 312, 1220–1223 10.1126/science.1127883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T., Prenen J., Fleig A., Vennekens R., Watanabe H., Hoenderop J. G., et al. (2001). CaT1 and the calcium release-activated calcium channel manifest distinct pore properties. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47767–47770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas J. M., Van Der Veen A. G., Ploegh H. L. (2008). The known unknowns of antigen processing and presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 607–618 10.1038/nri2368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Deng X., Mancarella S., Hendron E., Eguchi S., Soboloff J., et al. (2010). The calcium store sensor, STIM1, reciprocally controls Orai and CaV1.2 channels. Science 330, 105–109 10.1126/science.1191086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K. S., Miller M. J., Allen P. M. (2008). Th17 cells exhibit a distinct calcium profile from Th1 and Th2 cells and have Th1-like motility and NF-AT nuclear localization. J. Immunol. 180, 1442–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenning A. S., Neblung K., Strauss B., Wolfs M. J., Sappok A., Hoth M., et al. (2011). TRP expression pattern and the functional importance of TRPC3 in primary human T-cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 412–423 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. T., Manji S. S., Parker N. J., Hancock M. S., Van Stekelenburg L., Eid J. P., et al. (2001). Identification and characterization of the STIM (stromal interaction molecule) gene family: coding for a novel class of transmembrane proteins. Biochem. J. 357, 673–685 10.1042/0264-6021:3570673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woehrle T., Yip L., Elkhal A., Sumi Y., Chen Y., Yao Y., et al. (2010). Pannexin-1 hemichannel-mediated ATP release together with P2X1 and P2X4 receptors regulate T-cell activation at the immune synapse. Blood 116, 3475–3484 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. M., Buchanan J., Luik R. M., Lewis R. S. (2006a). Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 174, 803–813 10.1083/jcb.200604014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]