Abstract

Root colonization by selected Trichoderma isolates can activate in the plant a systemic defense response that is effective against a broad-spectrum of plant pathogens. Diverse plant hormones play pivotal roles in the regulation of the defense signaling network that leads to the induction of systemic resistance triggered by beneficial organisms [induced systemic resistance (ISR)]. Among them, jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) signaling pathways are generally essential for ISR. However, Trichoderma ISR (TISR) is believed to involve a wider variety of signaling routes, interconnected in a complex network of cross-communicating hormone pathways. Using tomato as a model, an integrative analysis of the main mechanisms involved in the systemic resistance induced by Trichoderma harzianum against the necrotrophic leaf pathogen Botrytis cinerea was performed. Root colonization by T. harzianum rendered the leaves more resistant to B. cinerea independently of major effects on plant nutrition. The analysis of disease development in shoots of tomato mutant lines impaired in the synthesis of the key defense-related hormones JA, ET, salicylic acid (SA), and abscisic acid (ABA), and the peptide prosystemin (PS) evidenced the requirement of intact JA, SA, and ABA signaling pathways for a functional TISR. Expression analysis of several hormone-related marker genes point to the role of priming for enhanced JA-dependent defense responses upon pathogen infection. Together, our results indicate that although TISR induced in tomato against necrotrophs is mainly based on boosted JA-dependent responses, the pathways regulated by the plant hormones SA- and ABA are also required for successful TISR development.

Keywords: Botrytis sp.,induced systemic resistance; jasmonic acid; phytohormone; priming; signaling; tomato; Trichoderma sp.

INTRODUCTION

Root colonization by selected Trichoderma isolates has been reported to increase resistance to different types of pathogens in various plant species, both below and aboveground (reviewed in Harman et al., 2004). This biological control can be achieved by a direct effect of Trichoderma on plant pathogens (reviewed in Vinale et al., 2008); or indirectly through plant-mediated effects by improving the plant nutritional status (Shoresh and Harman, 2008) or through partial activation of the plant immune system (reviewed in Shoresh et al., 2010). Indeed, some competent Trichoderma strains can colonize plants roots without any damage to plant tissues but inducing changes in plant physiology and the plant defense system (Yedidia et al., 1999; Alfano et al., 2007; Chacón et al., 2007; Brotman et al., 2012; Mathys et al., 2012). As in other beneficial plant–microbe interactions, these changes could be associated with a regulatory strategy of the plant to limit microbial colonization of the “ beneficial invader” (Zamioudis and Pieterse, 2012).

Although a clear understanding of the Trichoderma–plant recognition process is lacking, several elicitors that can activate plant basal immunity have been described in Trichoderma including the ethylene (ET)-inducing xylanase (Hanson and Howell, 2004); the proteinaceous non-enzymatic elicitor Sm1 (Djonovic et al., 2006, 2007); or the 18mer peptaibols (Viterbo et al., 2007). Only a limited number of pattern recognition receptors able to recognize some of these Trichoderma-related microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) have been characterized so far (Ron and Avni, 2004; Petutschnig et al., 2010). During the “ asymptomatic” infection of the roots, the plant limits the endophytic colonization of Trichoderma through the activation of certain plant defense responses, including cell wall reinforcement and the accumulation of antimicrobial compounds and reactive oxygen species (Yedidia et al., 1999, 2000; Chacón et al., 2007; Contreras-Cornejo et al., 2011; Salas-Marina et al., 2011). After the successful limitation of fungus penetration to the first few layers of root cortical cells, the expression of some defense-related genes and the antimicrobial activity return to pre-infection levels (Yedidia et al., 1999, 2003; Masunaka et al., 2011). It is likely that Trichoderma is able to “ short-circuit” plant defense signaling, possibly through the secretion of still unknown fungal effectors, which suppress plant defense to remain accommodated by the plant as an avirulent symbiont. The interaction between the plant and Trichoderma should then be finely regulated, assuring benefits to both partners, with the plant receiving protection and more available nutrients and the fungus obtaining organic compounds and a niche for growth.

Trichoderma colonization triggers, therefore, a wide array of plant responses which may result in an enhanced defensive capacity of the plant (Bailey et al., 2006; Marra et al., 2006; Alfano et al., 2007; Morán-Diez et al., 2012). Often, the effects of Trichoderma on the plant defense system are not restricted to the root, but they also manifest in aboveground plant tissues (Martínez-Medina et al., 2010, 2011a; Salas-Marina et al., 2011; Mathys et al., 2012), rendering the plant more resistant to a broad-spectrum of plant pathogens. This systemic resistance is likely the result of the modulation of the plant defense network that may translate Trichoderma-induced early signaling events into a more efficient activation of defense responses. It is well known that the phytohormones jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), abscisic acid (ABA), and ET act as dominant primary signals in the regulation of local and systemic defense responses in plants (reviewed in Pieterse et al., 2009), and accordingly, they play a central role in the induced resistance phenomena. Generally, pathogen-induced systemic acquired resistance (SAR), is dependent on the SA-regulated signaling pathway (Durrant and Dong, 2004), while ISR by beneficial microorganisms usually relies on JA signaling (Pieterse et al., 1996; Van Loon et al., 1998; Pozo et al., 2008; Van Wees et al., 2008; Van der Ent et al., 2009). However, as more resistance-inducing agents are characterized, the implication of other signaling pathways in the induction of resistance becomes evident. Indeed is the cross-talk among different signaling pathways what provides the plant with a powerful capacity to finely regulate its immune response to specific invaders (Pieterse et al., 2009), and as induced resistance is usually an enhancement of basal defenses, the implication of multiple hormones in shaping ISR is likely. Induced resistance may result of the direct activation of defense mechanisms – including increased basal levels of defense-related hormones, or of the priming of the plant defensive capacity. In the latter, a more efficient activation of defense mechanisms occurs upon attack, and it may not be related to changes in hormone content but in the susceptibility of the tissues to these hormones (Conrath et al., 2006).

Expression studies on marker genes linked to the main defense signaling pathways suggested that Trichoderma-induced systemic resistance (TISR) might involve the direct activation of both SA- and JA-related pathways (Alfano et al., 2007; Salas-Marina et al., 2011; Mathys et al., 2012; Morán-Diez et al., 2012). Despite this possible direct activation of defenses, most examples points to a boosted activation of defenses upon attack by several pathogens (Segarra et al., 2009; Perazzolli et al., 2011; Brotman et al., 2012; Mathys et al., 2012). Nevertheless, the activation of a pathway does not proof its role in resistance. The requirement of a specific signaling pathway in TISR can only be addressed by phenotypic studies of disease development on mutant lines impaired in those pathways, however, only a limited number of studies in the model plant Arabidopsis have addressed this issue. The pioneer study by Korolev et al. (2008) using multiple Arabidopsis mutant lines showed that the induction of resistance by Trichoderma harzianum Rifai T39 against Botrytis cinerea requires JA, ET, and ABA signaling, while SA was not required. Using different Trichoderma strains and the same Arabidopsis–B. cinerea pathosystem other authors have confirmed the requirement of JA for TISR, while the need of an intact SA and ET signaling pathways is more controversial (Segarra et al., 2009; Mathys et al., 2012). In summary, in Arabidopsis JA has been consistently reported as essential for TISR against B. cinerea and other pathogens, but the requirement of SA and ET may depend on the Trichoderma strain (Korolev et al., 2008; Segarra et al., 2009; Mathys et al., 2012).

According to the reported data, it is likely that the induction of resistance against specific pathogens in different hosts may require different signaling pathways. Although induction of TISR in tomato has been demonstrated against bacterial and fungal pathogens (Alfano et al., 2007; Tucci et al., 2011), the signaling pathways involved are yet to be investigated. Here we aim to gain further insights in the role of the main defense signaling pathways that operate in TISR in tomato against the major fungal pathogen B. cinerea (Dean et al., 2012). First we try to uncouple the role of plant defense mechanisms from the possible contribution of nutritional aspects. Then we analyzed the signaling pathways required for efficient TISR establishment through the phenotypic analysis of disease on tomato signaling mutants. Finally, we explore the plant defense response triggered upon pathogen attack in induced plants by monitoring the expression of defense-related marker genes.

In summary, we present an integrative analysis of the main mechanisms implicated in the systemic resistance induced by T. harzianum T-78 in an agronomically important crop, tomato, against the gray mold causal agent B. cinerea. The hormonal related pathways implicated in TISR have been analyzed in order to provide insights into the signaling network regulating systemic resistance induced by Trichodermain tomato.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MICROBIAL STRAINS AND INOCULA PREPARATION

Trichoderma harzianum T-78 (CECT 20714, Spanish collection of type cultures) inoculum was prepared using a specific solid medium, obtained by mixing commercial oat, bentonite, and vermiculite according to Martínez-Medina et al. (2009). The necrotrophic fungus used in this study was B. cinerea CECT2100 (Spanish collection of type cultures) kindly provided by Dr. Flors (Universidad de Valencia). For spore production, B. cinerea was cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco Laboratories, Detroit) supplemented with tomato leaves at 40 mg ml-1 at 24°C (Vicedo et al., 2009). B. cinerea spores were collected from 15-day-old cultures and incubated in Gambor’s B5 medium (Duchefa, Haarlem, The Netherlands) supplemented with 10 mM sucrose and 10 mM KH2PO4 for 2 h in the dark with no shaking, according to Vicedo et al. (2009).

PLANT MATERIAL

Ten different tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) genotypes were used in our studies including the four wild-type cultivars Castlemart, Moneymaker, UC82B, and Betterboy and the following defense-related mutant lines: The JA-impaired mutant def1 (Howe et al., 1996) in background Castlemart (provided by G. Howe, Michigan State University). The SA- and ABA-impaired lines NahG (Brading et al., 2000) and sitiens (Taylor et al., 1988) respectively, in background Moneymaker (provided by J. Jones, John Innes Centre and C. Hanhart, Wageningen University, respectively). The ET-impaired mutant ACD (Klee et al., 1991), in background UC82B (provided by H. Klee, University of Florida). The prosystemin antisense line PS- (Orozco-Cardenas et al., 1993) and the over-expressing line PS+ (McGurl et al., 1994) both in background Betterboy (provided by C. Ryan and G. Pearce, Washington State University). Seeds were surface-sterilized in 4% sodium hypochlorite containing 0.02% (v/v) Tween-20, rinsed thoroughly with sterile water and germinated for 1 week in sterile vermiculite at 25°C in darkness.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN AND GROWTH CONDITION

Individual seedlings were transferred to 0.25 l pots with a sterile sand:soil (4:1) mixture containing the Trichoderma inoculum. T. harzianum inoculum was mixed through the soil to a final density of 1 × 106 conidia per g of soil before transplanting the tomato seedlings. The same amount of sand:soil mix but free from T. harzianum was added to control plants. For each treatment a total of six plants were used. Plants were randomly distributed and grown in a greenhouse at 24/16°C with a 16/8 h photoperiod and 70% humidity, and watered three times a week with Long Ashton nutrient solution (Hewitt, 1966). After 5 weeks, plants were harvested and the roots and shoot fresh weights were determined. The fourth and fifth leaves of each plant were detached for inoculation with the pathogen, and the rest of the shoots reserved for nutritional analyses. Root samples of each individual plant were thoroughly rinsed and collected for microbiological analyses. Substrate attached to the root system was considered as rhizospheric substrate and reserved for microbiological analyses.

Botrytis cinerea BIOASSAY

The fourth and fifth leaves of each individual plant were detached from the plant with a blade and challenged with the pathogen by applying 5-μl droplets of a suspension of B. cinerea spores at 5 × 106 ml-1, previously incubated in Gambor’s B5 medium supplemented with sucrose (0.1 mM) and phosphate (0.1 mM) for 4 h (Vicedo et al., 2009). One leaflet of each detached leaf from control and T. harzianum-inoculated plants were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until use in molecular analyses as uninfected controls (time 0). Two 5-μl droplets were applied on each of the remaining leaflets, one on each side of the midrib. Detached Botrytis-inoculated leaves were placed on wet paper within plastic trays covered with transparent film to maintain high relative humidity conditions, and kept at 15–20°C with a photoperiod of 16 h light. Fungal hyphae grew concentrically from the inoculation site, resulting in visible necrosis at 48 h after inoculation. Disease symptoms were scored 72 and 96 h post inoculation (hpi) by determining the average lesion diameter in 12 leaves per genotype and treatment.

PLANT NUTRIENT CONTENT ANALYSES

Nutrient content of shoots was measured at CEBAS-CSIC (Spain). Leaves were briefly rinsed with deionized water and oven-dried at 60°C for 72 h, and ground to a fine powder. The samples were digested by a microwave technique, using a Milestone Ethos I microwave digestion instrument, according to Martínez-Medina et al. (2011b). A standard aliquot (0.1 g) of dry, finely ground plant material was digested with concentrated nitric acid (HNO3; 8 mL) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 2 mL). Subsequently, plant content of nutrition elements, including phosphorus and potassium, were simultaneous analyzed using ICP (Iris intrepid II XD2 Thermo). Nitrogen content was determined using a Flash 1112 series EA carbon/nitrogen analyzer. Six biological replicates from six independent plants were measured for each treatment.

Trichoderma QUANTIFICATION IN THE RHIZOSPHERE

Serial dilutions of the sand:soil mixture samples in sterile, quarter-strength ringer solution were used for quantifying T. harzianum colony forming units (cfu), by a plate count technique using PDA amended with 50 mg L-1 rose bengal and 100 mg L-1 streptomycin sulfate, according to Martínez-Medina et al. (2011b). Plates were incubated at 28°C and cfu were counted after 5 days. Data were expressed per gram of dry soil.

ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION BY RT-qPCR

Total RNA from tomato leaves was extracted using Tri-Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega), purified through a silica column using the NucleoSpin RNA Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel), and stored at -80°C until use. Leaf tissue was collected from tomato leaves 96 h upon pathogen infection. The second leaflet of the leaves also was collected as uninfected control. The complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, the conditions of RT-qPCR (reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction) experiments and the relative quantification of specific mRNA levels was performed according to López-Ráez et al. (2010) and using the gene-specific primers described in Table 1. Expression values were normalized using the housekeeping gene SlEF, which encodes for the tomato elongation factor-1α. The experiments were independently repeated and each reaction was performed in duplicate.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in the gene expression analysis. The genes monitored are used as markers for the pathways indicated. Jasmonate (JA), salicylic acid (SA), abscisic acid (ABA), and ethylene (ET)

| ID | Target Gen | Related pathway | Primer (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AF083253 | Multicystatin1 (MC) | JA inducible | GAGAATTTCAAGGAAGTTCAA |

| GGCTTTATTTCACACAGAGATA | |||

| K03291 | Proteinase inhibitor II1(PI II) | JA inducible | GAAAATCGTTAATTTATCCCAC |

| ACATACAAACTTTCCATCTTTA | |||

| M84801 | Prosystemin2(PS) | JA and ABA inducible | AATTTGTCTCCCGTTAGA |

| AGCCAAAAGAAAGGAAGCAAT | |||

| M69247 | Pathogenesis-related protein PR1a3 (PR1) | SA inducible | GTGGGATCGGATTGATATCCT |

| CCTAAGCCACGATACCATGAA | |||

| M83314 | Phenylalanine ammonia lyase2 (PAL) | SA biosynthesis | CGTTATGCTCTCCGAACATC |

| GAAGTTGCCACCATGTAAGG | |||

| X51904 | Desiccation protective protein3 (Le4) | ABA inducible | ACTCAAGGCATGGGTACTGG |

| CCTTCTTTCTCCTCCCACCT | |||

| NM001247876 | β-1,3-glucanase2 (gluB) | ET inducible | CCATCACAGGGTTCATTTAGG |

| CCATCCACTCTCTGACACAACT | |||

| X14449 | Elongation factor 1 α 4 (SlEF) | Housekeeping | GATTGGTGGTATTGGAACTGTC |

| AGCTTCGTGGTGCATCTC | |||

| XM_001560987.1 | β-tubulin5 | Quantification of B. cinereatubulin mRNA levels | CCGTCATGTCCGGTGTTACCAC |

| CGACCGTTACGGAAATCGGAA |

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data on lesion diameter in different tomato genotypes were subjected to two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The statistical significance of the results was determined by performing Tukey’s multiple-range test (P < 0.05). For data on plant nutritional content, pairwise comparisons were made for each genotype between Trichoderma-inoculated and control plants with Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). Regarding T. harzianum quantification in soil, the non-inoculated treatments were excluded from the analyses since T. harzianum was not detected in any of the non-inoculated treatments, and pairwise comparisons were made between each impaired mutant and its corresponding wild-type with Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). For gene expression analyses in the wild-type Moneymaker, pairwise comparisons were made for each gene between Trichoderma-inoculated and control plants with Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). Pairwise comparisons with Student’s t-test (P < 0.05) were also made for expression analysis between Trichoderma-inoculated and control plants for each gene in the genotypes def1 and Moneymaker. All the experiments were repeated at least 2 times, with similar results.

RESULTS

Trichoderma harzianum INDUCES SYSTEMIC PROTECTION AGAINST Botrytis cinerea INFECTION

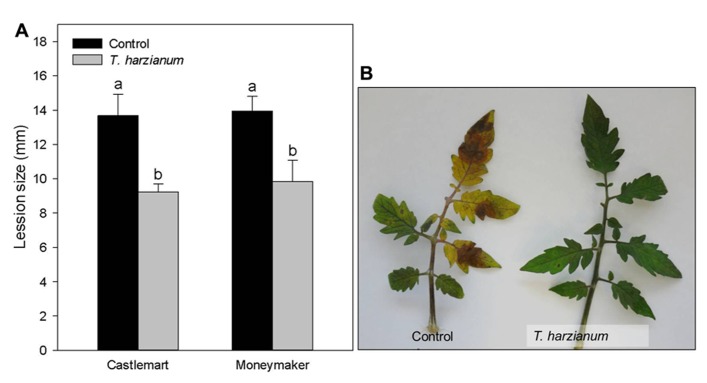

Five-weeks old plants of two different tomato cultivars (Castlemart and Moneymaker) inoculated with T. harzianum were challenged with the foliar pathogen B. cinerea. The progress of the disease was recorded and data corresponding to 96 hpi are shown. T. harzianum-inoculated plants resulted in a statistically significant reduction of lesion diameter in both cultivars,compared with untreated control plants (Figures 1A,B).

FIGURE 1.

Trichoderma harzianum induces systemic protection against the pathogen Botrytis cinerea in tomato plants.(A) Leaves of 5 weeks-old tomato plants (cv. Castlemart and Moneymaker) grown in soil containing or not T. harzianum were challenged with a conidial suspension of B. cinerea. Lesion diameter was determined 96 h after pathogen inoculation. The data show the lesion diameter (mm) ±SE (n = 12). Data not sharing a letter in common differ significantly (P < according to Tukey’s multiple-range test. (B) B. cinerea symptom development in T. harzianum inoculated and non-inoculated (control) plants (cv. Moneymaker).

THE SYSTEMIC PROTECTION TRIGGERED BY Trichoderma harzianum IN TOMATO IS NOT RELATED TO IMPROVED NUTRITION OR GROWTH PROMOTION

In order to determine the effect of T. harzianum on plant development, shoot and root fresh weighs were evaluated and nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium shoot content were measured on the tomato lines Castlemart and Moneymaker 5 weeks after inoculation with T. harzianum. There were no significant differences in growth associated to T. harzianum inoculation in any of the tomato lines (Table 2). Except for a moderate decrease in potassium levels in Castlemart, the nutrient analyses in shoots showed no differences in the main macronutrients nitrogen and phosphorous between Trichoderma-inoculated and control plants, suggesting that Trichoderma effects on disease development cannot be regarded as a consequence of improved plant growth or nutrition improvement.

Table 2.

Effect of Trichoderma harzianum on tomato plant development. Shoot and root fresh weight (in grams) and shoot nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium content (g/100 g fresh weigh) of 5-weeks old tomato lines Castlemart and Moneymaker inoculated with T. harzianum.

| Tomato Cv. | Treatment | Shoot fresh weight (g) | Root fresh weight (g) | Shoot nitrogen (g/100 g) | Shoot phosphorous (g/100 g) | Shoot potassium | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castlemart | Control | 9.90± 0.46 | 1.63 ± 0.16 | 2.69 ± 0.20 | 0.243 ± 0.054 | 2.54 ± 0.13 | |

| T. harzianum | 8.20 ± 0.30 | 1.67 ± 0.35 | 2.43 ± 0.21 | 0.174 ± 0.012 | 2.05 ± 0.09* | ||

| Moneymaker | Control | 10.15 ± 0.57 | 1.77 ± 0.15 | 1.90 ± 0.14 | 0.164 ± 0.045 | 2.30 ± 0.09 | |

| T. harzianum | 10.05 ± 0.69 | 1.32 ± 0.19 | 2.02 ± 0.34 | 0.124 ± 0.008 | 2.66 ± 0.24 |

The data are the means of six replicates ± SE. For each tomato genotype asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between T. harzianum inoculated and non-inoculated plants (Student’ s t-test, P < 0.05).

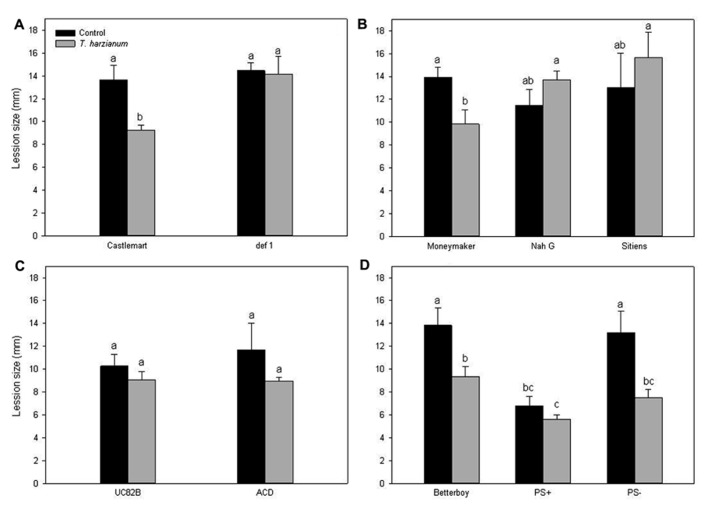

Trichoderma harzianum-INDUCED SYSTEMIC RESISTANCE IS DEPENDENT ON THE PHYTOHORMONES JA, SA, AND ABA

In order to analyze the involvement of different defense-related pathways in Trichoderma-mediated ISR, we investigated the effect of T. harzianum on B. cinerea infection in different tomato mutant lines and their corresponding backgrounds. Mutants affected in the biosynthesis of specific defense-related hormones were selected, including the JA-deficient defenseless1 (def1), the SA-deficient NahG, the ABA-deficient sitiens and the ET-underproducing ACC deaminase ACD. Additionally, we also analyzed the disease development in the tomato lines over-expressing the prosystemin gene in the sense (PS+) and antisense (PS-) orientation. Prosystemin is the precursor of the peptide defense hormone systemin, a positive regulator of JA signaling. The evaluation of the lesions upon Botrytis inoculation revealed that disease development was significantly affected by the plant genotype (P < 0.001; F = 7.43), the fungal treatment (P < 0.001; F = 10.98) and their interaction (P < 0.01; F = 2.82), as confirmed by two-way ANOVA analysis. As shown in Figure 2A the suppressive effect on B. cinerea disease observed in the wild-type Castlemart plants elicited with T. harzianum was absent in the JA-deficient def1 mutant, indicating that JA-regulated pathway is required for TISR against B. cinerea. Similarly, the mutant lines impaired in SA (NahG) and ABA (sitiens) accumulation did not display the TISR against B. cinerea observed in their corresponding background Moneymaker (Figure 2B). In the transgenic NahG line SA-accumulation is blocked through the transformation of SA to catechol. Interestingly, we observed a lower susceptibility of NahG control plants toward B. cinerea infection compared to its parental wild-type Moneymaker (P < 0.1), which support the idea that SA affect negatively basal resistance against this necrotroph in tomato (Figure 2B). In contrast to Castlemart and Moneymaker, the wild-type UC82B plants were unable to develop T. harzianum ISR (Figure 2C). In the ET-underproducing ACC deaminase mutants (ACD), T. harzianum slightly, but not significantly reduced the pathogen lesion (above 20%). Concerning systemin, plants of the over-expressing mutant line PS+, elicited and non-elicited with T. harzianum were more resistant to the necrotroph than any other cultivar tested (P < 0.05), confirming the involvement of this molecule in tomato basal resistance against B. cinerea. Although T. harzianum-induced resistance in the wild-type Betterboy, Trichoderma colonization could not reduce further B. cinerea disease development in PS+. Remarkably, T. harzianum was also able to induce ISR in the tomato line silenced in prosystemin expression PS- (Figure 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Trichoderma-induced systemic resistance requires JA, SA, and ABA. Lesion diameter was measured 96 h after challenge with the pathogen in (A) the wild-type tomato plants cv. Castlemart and the JA-impaired mutant def1; (B) in the wild-type cv. Moneymaker and the SA- and ABA-impaired mutants NahG and sitiens, respectively; (C) in the wild-type cv. UC82B and in the ET-impaired mutant ACD; and (D) in the wild-type cv. Betterboy and in the over-expressing mutant line PS+ and the prosystemin silenced line PS-. The data show the lesion diameter (mm) ± SE (n = 12). Data not sharing a letter in common differ significantly (P < 0.05) according to Tukey’s multiple-range test.

Trichoderma harzianum EFFECTIVELY COLONIZES THE RHIZOSPHERE AND ROOTS OF WILD-TYPE AND MUTANT TOMATO LINES

The biocontrol effect of Trichoderma is associated to its efficient colonization of the rhizosphere. To analyze if the unability of the mutants to mount TISR is related to a deficient Trichoderma colonization, we tested the ability of T. harzianum to colonize the rhizosphere of the different tomato mutant lines and their correspondent backgrounds. The number of Trichoderma colony-forming units (cfu) in the rhizosphere, determined after 5 weeks, was similar to initial inoculation values in all the tested lines. We did not find significant (P < 0.05) differences in cfu numbers in the rhizosphere of the different tomato mutant lines compared to their corresponding genetic backgrounds. Moreover, endophytic colonization was also confirmed for all of the lines. Incubation of surface-sterilized roots under appropriate conditions revealed that Trichoderma could outgrow from inside the roots regardless of the plant genotype. The results indicated that the impairment on the production of the hormones JA, SA, ABA, ET, or systemin does not affect T. harzianum capacity for rhizosphere and root colonization.

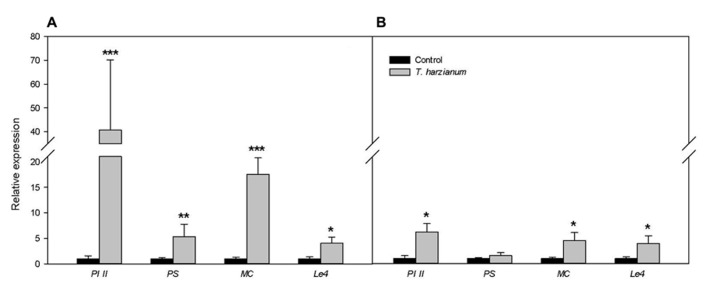

Trichoderma harzianum PRIMES JASMONATE-DEPENDENT DEFENSES

Induced systemic resistance by beneficial microbes is commonly not associated with major changes in defense-related gene expression. Instead, a relatively mild systemic immune reaction is triggered that is frequently associated with priming for enhanced defense. In order to establish whether the enhanced resistance induced by T. harzianum in tomato was associated with priming of plant defense, we compared the plant response to B. cinerea in Trichoderma elicited and not elicited plants. We analyzed by RT-qPCR the expression of known marker genes for the main plant defense-related pathways in B. cinerea challenged plants. No significant differences were found for the marker genes of SA- (PR1a and PAL) or ET- (gluB) modulated pathways between Trichoderma induced and not induced plants (data not shown). In contrast, an enhanced expression of the JA responsive genes PI II, MC, and PS, coding for proteinase inhibitor II, multicystatin, and prosystemin, respectively, was found in T. harzianum-elicited compared to non-elicited plants (Figure 3A). Interestingly, T. harzianum-inoculated plants showed no or slight induction of those genes in the absence of the pathogen (Figure 3B), thus pointing at priming of the JA-dependent defense responses as the mechanism underlying the induction of resistance against B. cinerea. T. harzianum-colonized plants also displayed higher levels of expression of the ABA responsive marker gene Le4 (coding for a desiccation protective protein) after pathogen challenge, but a similar increase was observed in T. harzianum induced plants in the absence of the pathogen (Figures3A,B).

FIGURE 3.

Trichoderma primes JA-regulated responses. The expression of different defense-related marker genes was analyzed in T. harzianum inoculated and non-inoculated (control) plants (cv. Moneymaker) 96 h upon pathogen infection (A) and before infection (B). Expression levels of the JA-related marker genes PI II, MC, and PS; and the ABA-related marker gene Le4 is shown. The results were normalized to the SlEF gene expression levels. The expression levels are reported as the fold increase relative to that of the control plants not treated with T. harzianum ± SE (n = 5). Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between Trichoderma induced and non-induced plants (Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

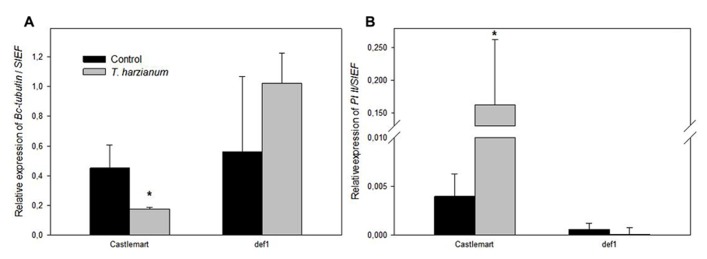

We further confirmed the priming of the JA-dependent defense responses against B. cinerea with the analysis of pathogen proliferation and the induction of JA responses in leaves of the wild-type Castlemart and the JA-deficient def1. Expression levels of a B. cinerea constitutive gene in leaves confirmed that the differences observed in symptom development (Figure 2) were due to differences in pathogen proliferation in the tissues, and confirmed that def1 plants were unable to develop Trichoderma-induced resistance in contrast to the wild-type Castlemart (Figure 4A). The inability of def1 plants to develop TISR correlated with a lack of priming of PI II expression (Figure 4B) further supporting the essential role of primed JA responses in the enhanced systemic resistance triggered by Trichoderma.

FIGURE 4.

Trichoderma harzianum priming of defenses requires JA signaling. The Botrytis cinerea constitutive gene Bc-Tubulin (A), and the JA-related marker gene PI II (B) were analyzed in leaves of the wild-type tomato plants cv. Castlemart and the JA-impaired mutant def1 upon 96 h of B. cinerea infection. Results were normalized to the SlEF gene expression in the same samples. Data show the relative expression level (±SE). For each tomato genotype asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between Trichoderma induced and non-induced plants (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05, n = 5).

DISCUSSION

Selected Trichoderma species colonize plant roots and establish symbiotic relationships with the plant. As consequence, plant resistance against pathogens is frequently enhanced, even in aboveground tissues (Segarra et al., 2009; Fontenelle et al., 2011; Perazzolli et al., 2011; Brotman et al., 2012; Yoshioka et al., 2012). In this study we analyzed the effectiveness of T. harzianum T-78 root colonization in the enhancement of tomato resistance against the foliar necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea. T. harzianum T-78 is an effective biocontrol agent in the soil (Martínez-Medina et al., 2011b), with high mycoparasitic capacity (López-Mondéjar et al., 2011), but its ability to induce plant resistance was not previously tested.

We found that treatment of tomato roots with T. harzianum T-78 clearly reduced disease development upon inoculation with the necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea in three out of four cultivars tested (Castlemart, Moneymaker, and Betterboy). We examined the presence of Trichoderma isolate T-78 in the shoots and we could not detect its presence in any of the tomato cultivars (data not shown). Therefore, Trichoderma and the pathogen remain physically separated, and accordingly, it can be concluded that T. harzianum T-78 activates a plant-mediated systemic response that is effective in restricting B. cinerea development. The dependence on the plant genotype of TISR against Botrytis, also shown for other tomato cultivars (Tucci et al., 2011), further confirms that the protection depends on plant-mediated mechanisms. Other studies have shown the ability of different Trichoderma strains to induce a plant-mediated effect against this necrotroph, mostly in Arabidopsis (Korolev et al., 2008; Contreras-Cornejo et al., 2011; Mathys et al., 2012) but also in other crop plants (De Meyer et al., 1998; Tucci et al., 2011).

Trichoderma colonization is reported to improve plant nutrition and growth in several plant species (Martínez-Medina et al., 2011b; Salas-Marina et al., 2011; Tucci et al., 2011). Since improved plant nutritional is considered one of the mechanisms responsible for bioprotection against pathogens by beneficial microorganisms (Whipps, 2001) we tried to analyze the contribution of this effect to the enhanced resistance observed. In our experimental conditions there was no increase in plant growth or nutrient content associated to Trichoderma colonization, probably because plants were grown under optimal conditions (Martínez-Medina et al., 2011b). Thus, our experimental system allows uncoupling nutritional from defense effects, and it can be concluded therefore that the protective effect observed in Trichoderma T-78-inoculated plants was related to mechanisms other than an improved nutrition, most likely related to plant defenses.

As for ISR by selected non-pathogenic rhizobacteria (Van Wees et al., 1999; Verhagen et al., 2004; Pozo et al., 2008), some studies have shown that the systemic resistance triggered by Trichoderma requires responsiveness to JA and ET (Shoresh et al., 2005; Segarra et al., 2009; Perazzolli et al., 2011; Tucci et al., 2011). However, phenotypic analysis of disease on Arabidopsis signaling mutants revealed that other small-molecule hormones such as SA or ABA could also play pivotal roles in the regulation of this network (Korolev et al., 2008; Mathys et al., 2012; Yoshioka et al., 2012). To determine the main signaling pathways involved in the induced systemic resistance elicited by T. harzianum T-78 in tomato against B. cinerea, we assessed the ability of different hormone-impaired tomato mutants for TISR development. The phenotypic analysis of disease development in the JA (def1)- and SA (NahG)-impaired mutants demonstrated that T. harzianum-induced systemic resistance against B. cinerea requires not only the JA but also the SA signaling pathways, as these mutant lines developed similar level of disease than non-induced control plants. Similarly, a recent study showed a role of the SA-pathway in T. hamatum T-382-induced ISR against B. cinerea in Arabidopsis, as TISR was blocked in the SA-impaired mutants NahG and sid2 (Mathys et al., 2012). In contrast, Trichoderma asperellum-induced resistance in Arabidopsis against the hemibiotrophic leaf pathogen Pseudomonas syringae seems independent of SA, as TISR was fully expressed in the SA-impaired mutant sid2 (Segarra et al., 2009). Thus experimental evidences support that induced resistance is a flexible process that may involve different signaling pathways depending on the mode of action of the pathogen, as it has been shown for some resistance-inducing chemicals (Flors et al., 2008). Our results demonstrate that in tomato, both SA and JA signaling pathways are required for TISR development against B. cinerea. Necrotrophic pathogens are usually controlled by JA-defense responses (Glazebrook, 2005), and JA signaling has been shown as key for basal resistance to Botrytis in tomato (AbuQamar et al., 2008; El-Oirdi et al., 2011). It is therefore not surprising the requirement of intact JA-related hormonal signaling pathway for boosted plant defenses against Botrytis by Trichoderma. The role of the SA signaling in plant resistance against B. cinerea is, however, more complex (Ferrari et al., 2003). Recently it has been shown that SA plays a regulatory role in the balance between disease and resistance as Botrytis induces SA signaling to promote disease in tomato through its negative interaction with the JA-dependent pathway (El-Oirdi et al., 2011).

In relation to ET, since the wild-type plants UC82B were unable to develop T. harzianum-induced ISR, we were unable to determine if ET signaling is required for TISR against B. cinerea. In contrast to earlier findings in rhizobacteria-mediated ISR (Pieterse et al., 1998; Knoester et al., 1999), Mathys et al. (2012) observed a limited role of the ET pathway in T. hamatum T382-induced resistance. Our results, although inconclusive, are in line with this finding as a reduced disease development on ET-mutants (ACD) was observed. It is noticeable that non-induced wild-type UC82B plants showed the lowest susceptibility to B. cinerea among all cultivars tested, and likely T. harzianum was unable to further boost plant resistance.

Additionally, analysis of the disease development in the ABA-deficient mutant sitiens showed that disruption of the ABA signaling results in the loss of ability to develop TISR against B. cinerea. Although ABA is commonly associated with plant development and abiotic stress, its role in plant immunity is now clear, as this hormone has been shown to be connected to the SA–JA–ET network (Anderson et al., 2004; Mauch-Mani and Mauch, 2005). The role of ABA in tomato resistance against pathogens is controversial, and indications for both a role in susceptibility and resistance have been given (Flors et al., 2008; Sánchez-Vallet et al., 2012). In tomato, a negative regulatory role of ABA in resistance to B. cinerea has been proposed, as the sitiens mutant showed reduced susceptibility than wild-type plants (Audenaert et al., 2002; Asselbergh et al., 2007, 2008). In our system sitiens plants did not show enhanced basal resistance compared to wild-type plants, indicating that ABA is not a major player in basal resistance, but it is important for Trichoderma-induced resistance. In line with these observations, Vicedo et al. (2009) found that ABA-deficient mutants were not affected in basal resistance against B. cinerea, but they were impaired in hexanoic acid-mediated protection against this pathogen, also based in primed JA responses.

Finally, systemin has been also shown to play a role in resistance against B. cinerea in tomato (Díaz et al., 2002; El-Oirdi et al., 2011). The disease examination in the over-expressing PS+ mutant line confirmed a role of the polypeptide in the basal resistance against B. cinerea, as over-expressing PS+ mutants were highly resistant to the necrotroph. Probably because of this high resistance, Trichoderma was unable to boost further resistance in this line. Remarkably, the analysis of the line silenced in prosystemin expression PS- showed that TISR was fully expressed in the PS- mutants suggesting that T. harzianum-mediated systemic resistance against B. cinerea does not rely on systemin signaling.

Trichoderma effects on plant defenses have been related to the fungal ability for intercellular root colonization (Yedidia et al., 2000; Chacón et al., 2007; Djonovic et al., 2007; Velázquez-Robledo et al., 2011). Successful rhizosphere and root endophytic colonization by T. harzianum T-78 was confirmed for all genotypes. Accordingly, the defect in TISR observed in some of the mutants is not related to defects in colonization but to the requirement of the hormone in the regulation of the plant response to the pathogen. The above findings demonstrate that T. harzianum-mediated resistance against B. cinerea requires the JA-, SA-, and ABA-regulated pathways. Cross-talk between hormonal-related signaling pathways acts as a cost-efficient regulatory mechanism for inducible defense responses (reviewed in Pieterse et al., 2009), and our results suggest that cross-talk between JA, SA, and ABA signaling pathways is essential for the induction of resistance mechanisms by Trichoderma T-78 in tomato. Nevertheless, it remains to be determined if additional hormones such as auxin, gibberellin, cytokinin, and brassinosteroids may also contribute to the regulatory network behind Trichoderma-induced resistance to B. cinerea.

Once key elements in the regulation of the response during TISR were identified, we aim to identify the actual defense responses underlying the resistance in Trichoderma-inoculated plants. For that we compared the plant defense response to Botrytis infection in Trichoderma elicited and not elicited plants through the expression analysis of known defense genes, markers for the main defense-related pathways. T. harzianum colonization of the roots resulted in priming of the aboveground plant tissues for enhanced JA-responsive gene expression, as a boosted expression of the JA-regulated marker genes PI II, PS, and MC coding for the proteinase inhibitor II (Farmer and Ryan, 1992), prosystemin, the precursor of the hormone systemin (Farmer and Ryan, 1992) and multicystatin (Girard et al., 2007) was observed in Trichoderma-induced plants, upon B. cinerea infection. It has been recently reported that the proteinase inhibitor II encoded for PI II plays a major role for tomato resistance against B. cinerea (El-Oirdi et al., 2011). The induction of those genes in plant shoots by Trichoderma was relatively weak before Botrytis infection, thus pointing to priming of the JA-dependent defense responses as the mechanism underlying the induction of resistance against B. cinerea. Activation of a JA-related priming state in plants by Trichoderma has been observed previously in Arabidopsis, tomato, and grapevine plants (Segarra et al., 2009; Tucci et al., 2011; Brotman et al., 2012; Perazzolli et al., 2012) with no obvious costs for the plant. Indeed, priming by beneficial microorganisms offers broad-spectrum protection whenever required (Van der Ent et al., 2009), without significant energy costs to plant metabolism and growth (Walters and Heil, 2007; Van Wees et al., 2008). Trichoderma elicitation, however, did not boost SA- or ET-related defense responses against B. cinerea, as no variation in the SA-marker genes PR1a and PAL nor in the ET regulated gluB were found in our study, in contrast to earlier studies (Yedidia et al., 2003; Shoresh et al., 2005). Nevertheless, as resistance to B. cinerea is JA-dependent (AbuQamar et al., 2008) and SA signaling is the target of the pathogen to interfere with JA-signaling and promote disease (El-Oirdi et al., 2011), priming of SA responses in this interaction would be detrimental for the plant. Notably, Trichoderma inoculation induced the expression of the ABA-marker gene Le4 before B. cinerea infection, suggesting a moderate direct activation of ABA-signaling that could participate in the defense against the pathogen.

The identification of primed JA responses as the control mechanism underlying TISR in tomato- B. cinerea pathosystem was further corroborated in the JA-impaired mutant def1 through the quantification of pathogen biomass and the induction of plant defenses. The failure of def1 plants to develop TISR correlated with a lack of priming for PI II expression. These results confirm the essential role of the boosted expression of JA responses in the enhancement of resistance by Trichodermaagainst B. cinerea.

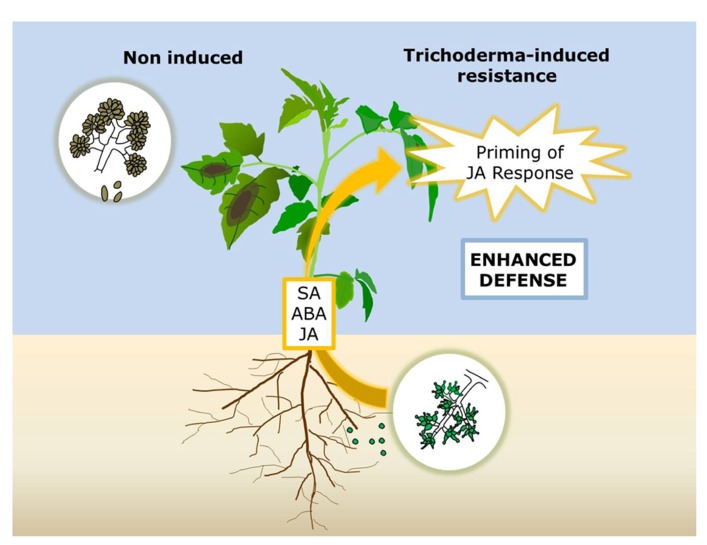

In summary, this study provides evidence that T. harzianum induces systemic resistance against B. cinerea in tomato through a boosted JA-dependent defense response, which reduce pathogen proliferation and disease development in plant leaves. The regulation of the response requires not only JA but also at least SA and ABA signaling (Figure 5). All in all, our results support the consistent central role of JA in the induction of resistance by different Trichoderma strains, and illustrate the requirement of other signaling pathways probably shaping the final response adapted to the challenging pathogen.

FIGURE 5.

Model for Trichoderma-induced resistance (TISR) against Botrytis cinerea in tomato. Root colonization with Trichoderma primes leaf tissues for enhanced activation of JA-regulated defense responses leading to a higher resistance to the necrotroph. Intact JA, SA, and ABA signaling pathways are required for TISR development.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Saskia Van Wees and Dr. Juan A. López Ráez for useful comments on the manuscript, and Juan M. García for technical assistance. This research was supported by grants AGL2009-07691 from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology and by the CYCIT project AGL2010 21073 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

REFERENCES

- AbuQamar S., Chai M.-F., Luo H., Song F., Mengiste T. (2008) Tomato protein kinase 1b mediates signaling of plant responses to necrotrophic fungi and insect herbivory. Plant Cell 20 1964–1983 10.1105/tpc.108.059477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano G., Lewis Ivey M. L., Cakir C., Bos J. I. B., Miller S. A., Madden L. V., et al. (2007) Systemic modulation of gene expression in tomato by Trichoderma hamatum 382. Phytopathology 97 429–437 10.1094/PHYTO-97-4-0429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J. P., Badruzsaufari E., Schenk P. M., Manners J. M., Desmond O. J., Ehlert C., et al. (2004) Antagonistic interaction between abscisic acid and jasmonate-ethylene signaling pathways modulates defense gene expression and disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16 3460–3479 10.1105/tpc.104.025833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselbergh B., Achuo A. E., Höfte M., Van Gijsegem F. (2008) Abscisic acid deficiency leads to rapid activation of tomato defence responses upon infection with Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9 11–24 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00437.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselbergh B., Curvers K., França S. C., Audenaert K., Vuylsteke M., Van Breusegem F., et al. (2007) Resistance to Botrytis cinerea in sitiens, an abscisic acid-deficient tomato mutant, involves timely production of hydrogen peroxide and cell wall modifications in the epidermis. Plant Physiol.144 1863–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audenaert K., De Meyer G. B, Höfte M. M. (2002) Abscisic acid determines basal susceptibility of tomato to Botrytis cinerea and suppresses salicylic acid-dependent signaling mechanisms. Plant Physiol. 128 491–501 10.1104/pp.010605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey B. A., Bae H., Strem M. D., Roberts D. P., Thomas S. E., Crozier J., et al. (2006) Fungal and plant gene expression during the colonization of cacao seedlings by endophytic isolates of four Trichoderma species. Planta 224 1449–1464 10.1007/s00425-006-0314-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brading P. A., Hammond-Kosack K. E., Parr A., Jones J. D. G. (2000) Salicylic acid is not required for cf-2- and cf-9-dependent resistance of tomato to Cladosporium fulvum. Plant J. 23 305–318 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00778.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman Y., Lisec J., Méret M., Chet I., Willmitzer L., Viterbo A. (2012) Transcript and metabolite analysis of the Trichoderma-induced systemic resistance response to Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis thaliana.Microbiology 158 139–146 10.1099/mic.0.052621-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer M., Lievens B., Van Hemelrijck W., Van Den Ackerveken G., Cammue B. P. A, Thomma B. P. H. J. (2003) Quantification of disease progression of several microbial pathogens on Arabidopsis thaliana using real-time fluorescence PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 228 241–248 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00759-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón M. R., Rodriguez-Galan O., Benítez T., Sousa S., Rey M., Llobell A., et al. (2007) Microscopic and transcriptome analyses of early colonization of tomato roots by Trichoderma harzianum. Int. Microbiol. 10 19–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U., Beckers G. J. M., Flors V., García-Agustín P., Jakab G., Mauch F., et al. (2006) Priming: getting ready for battle. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19 1062–1071 10.1094/MPMI-19-1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Cornejo H. A., Macías-Rodríguez L., Beltrán-Peña E., Herrera-Estrella A., López-Bucio J. (2011) Trichoderma-induced plant immunity likely involves both hormonal- and camalexin dependent mechanisms in Arabidopsis thaliana and confers resistance against necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Plant Signal.Behav. 6 1554–1563 10.4161/psb.6.10.17443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean R., Van Kan J. A. L., Pretorius Z. A., Hammond-Kosack K. E., Di Pietro A., Spanu P. D., et al. (2012) The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. PlantPathol. 13 414–430 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.0783.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer G., Bigirimana J., Elad Y., Höfte M. (1998) Induced systemic resistance in Trichoderma harzianum T39 biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 104 279–286 10.1023/A:1008628806616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz J., Ten Have A., van Kan J. A. L. (2002) The role of ethylene and wound signaling in resistance of tomato to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 129 1341–1351 10.1104/pp.001453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djonovic S., Pozo M. J., Dangott L. J., Howell C. R., Kenerley C. M. (2006) Sm1, a proteinaceous elicitor secreted by the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma virens induces plant defense responses and systemic resistance. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19 838–853 10.1094/MPMI-19-0838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djonovic S., Vargas W. A., Kolomiets M. V., Horndeski M., Wiest A., Kenerley C. M. (2007) A proteinaceous elicitor Sm1 from the beneficial fungus Trichoderma virens is required for induced systemic resistance in maize. Plant Physiol. 145 875–899 10.1104/pp.107.103689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant W. E., Dong X. (2004) Systemic acquired resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42 185–209 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Oirdi M., El-Rahman T. A., Rigano L., El-Hadrami A., Rodriguez M. C., Daayf F., et al. (2011) Botrytis cinerea manipulates the antagonistic effects between immune pathways to promote disease development in tomato. Plant Cell 23 2405–2421 10.1105/tpc.111.083394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer E. E., Ryan C. A. (1992) Octadecanoid precursors of jasmonic acid activate the synthesis of wound-inducible proteinase inhibitors. Plant Cell 4 129–134 10.1105/tpc.4.2.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari S., Plotnikova J. M., De Lorenzo G., Ausubel F. M. (2003) Arabidopsis local resistance to Botrytis cinerea involves salicylic acid and camalexin and requires EDS4 and PAD2, but not SID2, EDS5 or PAD4. Plant J. 35 193–205 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flors V., Ton J., Van Doorn R., Jakab G., García-Agustín P., Mauch-Mani B. (2008)Interplay between JA, SA and ABA signalling during basal and induced resistance against Pseudomonas syringae and Alternaria brassicicola. Plant J. 54 81–92 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenelle A. D. B., Guzzo S. D., Lucon C. M. M., Harakava R. (2011) Growth promotion and induction of resistance in tomato plant against Xanthomonas euvesicatoria and Alternaria solani by Trichoderma spp. Crop Prot. 30 1492–1500 10.1016/j.cropro.2011.07.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Girard C., Rivard D., Kiggundu A., Kunert K., Gleddie S. C., Cloutier C., et al. (2007) A multicomponent, elicitor-inducible cystatin complex in tomato, Solanum lycopersicum. NewPhytol. 173 841–851 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.01968.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J. (2005) Contrasting mechanisms of defense against biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43 205–227 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson L. E., Howell C. R. (2004) Elicitors of plant defense responses from biocontrol strains of Trichoderma virens. Phytopathology 94 171–176 10.1094/PHYTO.2004.94.2.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman G. E., Howell C. R., Viterbo A., Chet I., Lorito M. (2004) Trichoderma species-opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 43–56 10.1038/nrmicro797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt E. J. (1966) Sand and Water Culture Methods Used in the Study of Plant Nutrition. Technical communication no. 22 London: Commonwealth Agriculture Bureau; 10.1007/s00294-006-0091-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howe G. A., Lightner J., Browse J., Ryan C. A. (1996) An octadecanoid pathway mutant (JL5) of tomato is compromised in signaling for defense against insect attack. Plant Cell 8 2067–2077 10.1105/tpc.8.11.2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee H. J., Hayford M. B., Kretzmer K. A., Barry G. F., Kishore G. M. (1991) Control of ethylene synthesis by expression of a bacterial enzyme in transgenic tomato plants. Plant Cell 3 1187–1193 10.1105/tpc.3.11.1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoester M., Pieterse C. M. J., Bol J. F, Van Loon L. C. (1999) Systemic resistance in Arabidopsis induced by Rhizobacteria requires ethylene-dependent signaling at the site of application. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 12 720–727 10.1094/MPMI.1999.12.8.720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolev N., Rav David D., Elad Y. (2008)The role of phytohormones in basal resistance and Trichoderma-induced systemic resistance to Botrytis cinerea in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biocontrol 53 667–683 10.1007/s10526-007-9103-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Mondéjar R., Ros M., Pascual J. A. (2011) Mycoparasitism-related genes expression of Trichoderma harzianum isolates to evaluate their efficacy as biological control agent. Biol. Control 56 59–66 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Ráez J. A., Verhage A., Fernández I., García J. M., Azcón-Aguilar C., Flors V., et al. (2010) Hormonal and transcriptional profiles highlight common and differential host responses to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and the regulation of the oxylipin pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 61 2589–2601 10.1093/jxb/erq089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra R., Ambrosino P., Carbone V., Vinale F., Woo S. L., Ruocco M., et al. (2006) Study of the three-way interaction between Trichoderma atroviride, plant and fungal pathogens by using a proteomic approach. Curr. Genet. 50 307–321 10.1007/s00294-006-0091-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martïnez-Medina A., Pascual J. A., Pérez-Alfocea F., Albacete A., Roldán A. (2010) Trichoderma harzianum and Glomus intraradices modify the hormone disruption induced by Fusarium oxysporum infection in melon plants. Phytopathology 100 682–688 10.1094/PHYTO-100-7-0682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martïnez-Medina A., Roldán, A., Albacete A., Pascual J. A. (2011a) The interaction with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi or Trichoderma harzianum alters the shoot hormonal profile in melon plants. Phytochemistry 72 223–229 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Medina A., Roldán A., Pascual J. A. (2011b).Interaction between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Trichoderma harzianum under conventional and low input fertilization field condition in melon crops: growth response and Fusarium wilt biocontrol. Appl. Soil Ecol. 47 98–105 10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.11.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Medina A., Roldán A., Pascual J. A. (2009) Performance of a Trichoderma harzianum bentonite–vermiculite formulation against Fusarium wilt in seedling nursery melon plants. HortScience 44 2025–2027 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.11.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masunaka A., Hyakumachi M., Takenaka S. (2011) Plant growth-promoting fungus, Trichoderma koningisuppresses isoflavonoid phytoalexin vestitol production for colonization on/in the roots of Lotus japonicus. Microbes Environ. 26 128–134 10.1264/jsme2.ME10176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathys J., De Cremer K., Timmermans P., Van Kerckhove S., Lievens B., Vanhaecke M., et al. (2012) Genome-wide characterization of ISR induced in Arabidopsis thaliana by Trichoderma hamatum T382 against Botrytis cinerea infection. Front. Plant Sci. 3: 108 10.3389/fpls.2012.00108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauch-Mani B., Mauch F. (2005) The role of abscisic acid in plant-pathogen interactions. Curr.Opin. Plant Biol. 8 409–414 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurl B., Orozco-Cardenas M., Pearce G., Ryan C. A. (1994) Overexpression of the prosystemin gene in transgenic tomato plants generates a systemic signal that constitutively induces proteinase inhibitor synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 9799–9802 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morán-Diez E., Rubio B., Domïnguez S., Hermosa R., Monte E., Nicolás C. (2012) Transcriptomic response of Arabidopsis thaliana after 24h incubation with the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma harzianum. J. Plant Physiol. 169 614–620 10.1016/j.jplp.2011.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Cardenas M., McGurl B., Ryan C. A. (1993) Expression of an antisense prosystemin gene in tomato plants reduces resistance toward Manduca sexta larvae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 8273–8276 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perazzolli M., Moretto M., Fontana P., Ferrarini A., Velasco R., Moser C., et al. (2012) Downy mildew resistance induced by Trichoderma harzianum T39 in susceptible grapevines partially mimics transcriptional changes of resistant genotypes. BMC Genomics 13: 660 10.1186/1471-2164-13-660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perazzolli M., Roatti B., Bozza E., Pertot I. (2011) Trichoderma harzianumT39 induces resistance against downy mildew by priming for defense without costs for grapevine. Biol. Control 58 74–82 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2011.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petutschnig E. K., Jones A. M. E., Serazetdinova L., Lipka U., Lipka V. (2010) The Lysin Motif Receptor-Like Kinase (LysM-RLK) CERK1 is a major chitin-binding protein in Arabidopsis thaliana and subject to chitin-induced phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 285 28902–28911 10.1074/jbc.P110.116657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C. M. J., Leon-Reyes A., Van der Ent S., Van Wees S. C. M. (2009) Networking by small-molecule hormones in plant immunity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5 308–316 10.1038/nchembio.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C. M. J., Van Wees S. C. M., Hoffland E., Van Pelt J. A, Van Loon L. C. (1996) Systemic resistance in Arabidopsis induced by biocontrol bacteria is independent of salicylic acid accumulation and pathogenesis-related gene expression. Plant Cell 8 1225–1237 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse C. M. J., Van Wees S. C. M., Van Pelt J. A., Knoester M., Laan R., Gerrits H., et al. (1998) A novel signaling pathway controlling induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10 1571–1580 10.1105/tpc.10.9.1571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozo M. J., Van Der Ent S., Van Loon L. C, Pieterse C. M. J. (2008)Transcription factor MYC2 is involved in priming for enhanced defense during rhizobacteria-induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 180 511–523 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron M., Avni A. (2004) The receptor for the fungal elicitor ethylene-inducing xylanase is a member of a resistance-like gene family in tomato. Plant Cell 16 1604–1615 10.1105/tpc.022475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg D., Thompson T. S., German T. L., Willis D. K. (2006) Methods for effective real-time RT-PCR analysis of virus-induced gene silencing. J. Virol. Methods 138 49–59 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Marina M. A., Silva-Flores M. A., Uresti-Rivera E. E., Castro-Longoria E., Harrera-Estrella A., Casas-Flores S. (2011) Colonization of Arabidopsis roots by Trichoderma atroviride promotes growth and enhances systemic disease resistance through jasmonate and salicylate pathways. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 131 15–26 10.1007/s10658-011-9782-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vallet A., López G., Ramos B., Delgado-Cerezo M., Riviere M. P., Llorente F., et al. (2012) Disruption of abscisic acid signaling constitutively activates Arabidopsis resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Plectosphaerella cucumerina. Plant Physiol. 160 2109–2124 10.1016/S0981-9428(00)01198-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra G., Van der Ent S., Trillas I., Pieterse C. M. J. (2009) MYB72, a node of convergence in induced systemic resistance triggered by a fungal and a bacterial beneficial microbe. Plant Biol. 11 90–96 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00162.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M., Harman G. E. (2008)The relationship between increased growth and resistance induced in plants by root colonizing microbes. Plant Signal. Behav. 3 737–739 10.4161/psb.3.9.6605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M., Harman G. E., Mastouri F. (2010) Induced systemic resistance and plant responses to fungal biocontrol agents. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48 21–43 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoresh M., Yedidia I., Chet I. (2005) Involvement of jasmonic acid/ethylene signaling pathway in the systemic resistance induced in cucumber by Trichoderma asperellum T203. Phytopathology 95 76–84 10.1094/PHYTO-95-0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor I. B., Linforth R. S. T., Al-Naieb R. J., Bowman W. R., Marples B. A. (1988) The wilty tomato mutants flacca and sitiens are impaired in the oxidation of ABA-aldehyde to ABA. Plant Cell Environ. 11 739–745 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1988.tb01158.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci M., Ruocco M., De Masi L., De Palma M., Lorito M. (2011) The beneficial effect of Trichoderma spp. on tomato is modulated by the plant genotype. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12 341–354 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00674.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppalapati S. R., Ayoubi P., Weng H., Palmer D. A., Mitchell R. E., Jones W., et al. (2005) The phytotoxin coronatine and methyl jasmonate impact multiple phytohormone pathways in tomato. Plant J. 42 201–217 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ent S., Van Wees S. C. M, Pieterse C. M. J. (2009) Jasmonate signaling in plant interactions with resistance-inducing beneficial microbes. Phytochemistry 70 1581–1588 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon L. C., Bakker P. A. H. M., Pieterse C. M. J. (1998) Systemic resistance induced by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 36 453–483 10.1146/annurev.phyto.36.1.453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wees S. C. M., Luijendijk M., Smoorenburg I., Van Loon L. C, Pieterse C. M. J. (1999) Rhizobacteria-mediated induced systemic resistance (ISR) Arabidopsis is not associated with a direct effect on expression of known defense-related genes but stimulates the expression of the jasmonate-inducible gene Atvsp upon challenge. Plant Mol. Biol. 41 537–549 10.1023/A:1006319216982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wees S. C. M., Van der Ent S., Pieterse C. M. J. (2008)Plant immune responses triggered by beneficial microbes. Curr.Opin. Plant Biol. 11 443–448 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Robledo R., Contreras-Cornejo H. A., Macías-Rodrïguez L., Hernández-Morales A., Aguirre J., Casas-Flores S., et al. (2011) Role of the 4-phosphopantetheinyl transferase of Trichoderma virens in secondary metabolism and induction of plant defense responses. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24 1459–1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen B. W. M., Glazebrook J., Zhu T., Chang H. S., Van Loon L. C, Pieterse C. M. J. (2004) The transcriptome of rhizobacteria-induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 17 895–908 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.8.895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicedo B., Flors V., Leyva M. D. O., Finiti I., Kravchuk Z., Real M. D., et al. (2009) Hexanoic acid-induced resistance against Botrytis cinerea in tomato plants. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22 1455–1465 10.1094/MPMI-22-11-1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinale F., Sivasithamparam K., Ghisalberti E. L., Marra R., Woo S. L., Lorito M. (2008)Trichoderma-plant-pathogen interactions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40 1–10 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viterbo A., Wiest A., Brotman Y., Chet I., Kenerley C. (2007) The 18merpeptaibols from Trichoderma virens elicit plant defense responses. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8 737–746 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters D., Heil M. (2007) Costs and trade-offs associated with induced resistance. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol., 71 3–17 10.1016/j.pmpp.2007.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whipps J. M. (2001) Microbial interactions and biocontrol in the rhizosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 52 487–511 10.1093/jexbot/52.suppl_1.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedidia I., Benhamou N., Chet I. (1999) Induction of defense responses in cucumber plants (Cucumis sativus L.)by the biocontrol agent Trichoderma harzianum.Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 1061–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedidia I., Benhamou N., Kapulnik Y., Chet I. (2000) Induction and accumulation of PR proteins activity during early stages of root colonization by the mycoparasite Trichoderma harzianum strain T-203. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 38 863–873 10.1016/S0981-9428(00)01198-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yedidia I., Shoresh M., Kerem Z., Benhamou N., Kapulnik Y., Chet I. (2003) Concomitant induction of systemic resistance to Pseudomonas syringae pv.lachrymans in cucumber by Trichoderma asperellum (T-203) and accumulation of phytoalexins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 7343–7353 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7343-7353.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka Y., Ichikawa H., Naznin H. A., Kogure A., Hyakumachi M. (2012) Systemic resistance induced in Arabidopsis thaliana by Trichoderma asperellum SKT-1, a microbial pesticide of seedborne diseases of rice. Pest Manag. Sci. 68 60–66 10.1002/ps.2220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamioudis C., Pieterse C. M. J. (2012) Modulation of host immunity by beneficial microbes. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 25 139–150 10.1094/MPMI-06-11-0179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]