Abstract

The functional impact of amyloid peptides (Aβs) on the vascular system is less understood despite these pathologic peptides are substantially deposited in the brain vasculature of Alzheimer's patients. Here we show substantial accumulation of Aβs 40 and 42 in the brain arterioles of Alzheimer's patients and of transgenic Alzheimer's mice. Purified Aβs 1–40 and 1–42 exhibited vascular regression activity in the in vivo animal models and vessel density was reversely correlated with numbers and sizes of amyloid plaques in human patients. A significant high number of vascular cells underwent cellular apoptosis in the brain vasculature of Alzheimer's patients. VEGF significantly prevented Aβ-induced endothelial apoptosis in vitro. Neuronal expression of VEGF in transgenic mice restored memory behavior of Alzheimer's. These findings provide conceptual implication of improvement of vascular functions as a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease.

Emerging evidence shows that development and progression of Alzheimer's disease (AD), the major cause of dementia in the elder population, are associated with vascular dysfunctions in the central nerve system (CNS)1. Despite the early notion that the amyloid senile plaques are accumulated within arterioles2,3,4, little is known about the functional impairment of amyloid peptides in the vascular system. The vasculature in CNS plays an essential role in maintenance of physiological functions of the brain. In addition to supplying nutrients and oxygen to nerve cells, vascular endothelial cells and peri-vascular mural cells interact with nerve cells and glia cells by secreting a number of neurotrophic factors5. These vascular cell-derived paracrine factors may not need to bypass the blood-brain barrier to communicate with the neuronal cells. Recent evidence shows that circulating cells derived from bone marrow may also serve as a reservoir for supplying pluripotent stem cells that can differentiate into neuronal cells6,7. Thus, the vascular compartment plays a pivotal role in modulating neuronal cell function, in renewal of cell populations, and in repairing neuronal damages. For this reason, it is probably not surprising that CNS is one of the most vascularized tissues in the body.

Conversely, neuronal cells cross-communicate with vascular cells by producing a range of growth factors targeting both endothelial cells (ECs) and vascular mural cells (VMCs), the latter include pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)8,9. Among neuronal cell-derived growth factors, vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) is abundantly expressed in CNS10. In fact, VEGF was first discovered from the brain tissue 20 years ago8. VEGF displays broad biological functions including modulation of angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, vascular permeability, vascular remodelling, vascular survival, arterial differentiation, neurotrophic activity, hematopoiesis and inflammatory responses11,12. Deletion of only one allele of the vegf gene in mice leads to early embryonic lethality due to lack of hematopoietic and vascular systems, suggesting that the levels of VEGF are crucial for embryonic development and maintenance of the physiological functions13,14. In several physiologically and pathologically experimental settings, VEGF has been demonstrated to act as a survival factor for the vasculature in various tissues and organs15. For example, inhibition of VEGF by specific blockades in adult healthy mice resulted in regression of blood vessels in multiple tissues and organs, indicating the necessity of VEGF in protecting the integrity of the vasculature16. The broad biological functions of VEGF are mediated by its tyrosine kinase receptors (TKRs) distributed in ECs and non-ECs, which include VEGFR1, and VEGFR212,17. The signalling pathways mediated by these TKRs to execute VEGF-induced vascular and non-vascular functions have extensively characterized during the past few decades. Additionally, VEGF also binds to neuropilin-1/-2 that involves exon-guidance and vascular sprouting events during nerve and vessel growth18. In fact, nerve growth and vascular development are tightly coupled and share common mechanisms by employing an overlapping set of molecular players19,20,21.

In the light of the pivotal functions of the vascular system in CNS and the vascular destructive activity of Aβs, in the present work we have studied vascular damage emanating from Aβs in AD animal models and human patient samples. We show that Aβs exhibited apoptotic effects on ECs and VEGF could significantly rescue the Aβs-induced vascular damage. Notably, overexpression of VEGF in CNS by a transgenic mouse model substantially protects the vascular integrity and functionally rescues mice from memory impairments. These findings have paved a new avenue for therapeutic development of VEGF and probably other angiogenic factors for the treatment of CNS disorders such as AD.

Results

Accumulation of Aβ-40 and 42 in brain arterioles of AD patients

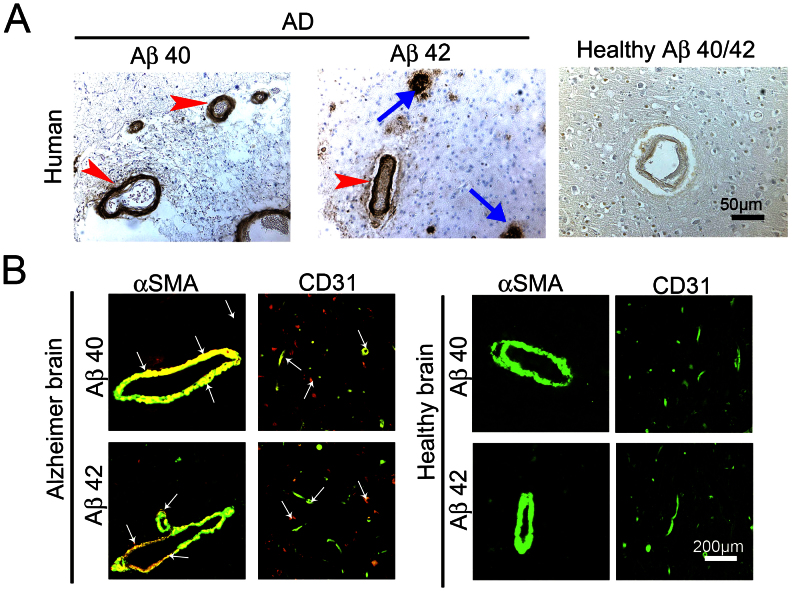

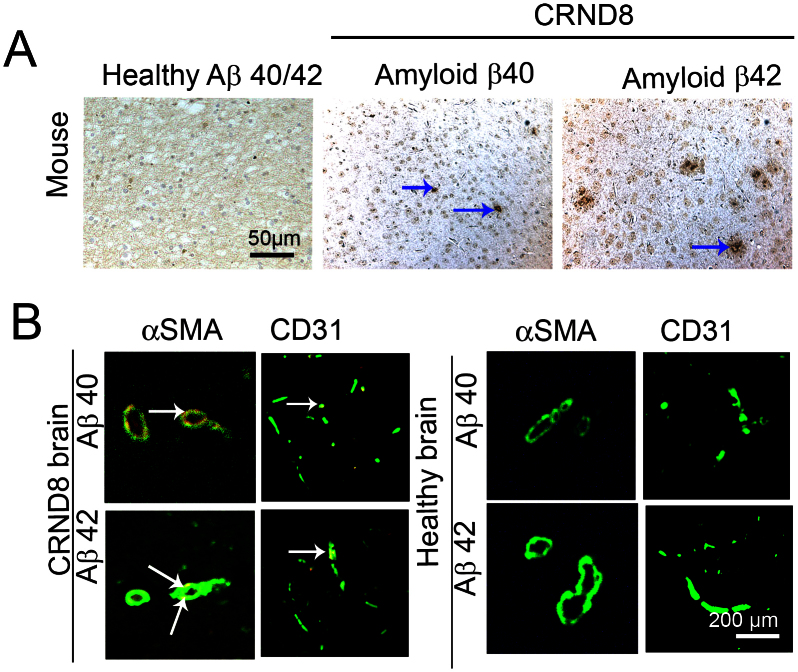

To study the association of Aβs with the brain vasculature, the frontal cortex of 15 AD patients and 12 healthy individuals were used to localize Aβ-40 and Aβ-42 by specific antibodies22. The patient information was shown in Table 1. As expected, amyloid plaques of Aβ-40 and Aβ-42 were present only in the brain tissue of AD patients but not in healthy controls (Fig. 1A arrows)23. Surprisingly, substantial amounts of Aβ-40 and Aβ-42 were found within blood vessels in the brain tissue of AD patients (Fig. 1A arrowheads). In contrast, no positive signals were detected in the brain tissue of healthy controls. To reveal the identity of the Aβ-40 and Aβ-42-associated relatively large vessels, AD brain tissues were double-stained with an arteriole marker, α-SMA, and Aβ-40 or Aβ-42. Interestingly, a considerable number of α-SMA+ vessels exhibited Aβ-40 and Aβ-42 staining, demonstrating that Aβs are accumulated in the arterioles (Fig. 1B). In some areas of AD samples, Aβ-40 and Aβ-42 were only found within the vascular system, but lacked obvious extra vascular amyloid plaques. Similarly, CD31 and Aβ double staining revealed that a significant number of brain microvessels were also affected by Aβ-40 and Aβ-42 (Fig. 1B).

Table 1. Demographic information of Alzheimer patients and controls*.

| Patient No | Age (year) | Gender | Clinical dementia | Braak and Braak Stage (pkt)23 | Amyloid deposit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD Patient | |||||

| 1 | 80 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 2 | 93 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 3 | 73 | f | yes | 5 | yes |

| 4 | 67 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 5 | 83 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 6 | 79 | m | yes | 6 | yes |

| 7 | 80 | m | yes | 6 | yes |

| 8 | 86 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 9 | 89 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 10 | 76 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 11 | 77 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 12 | 74 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 13 | 87 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 14 | 90 | f | yes | 6 | yes |

| 15 | 62 | m | yes | 6 | yes |

| Non-AD control | |||||

| 16 | 51 | m | no | 0 | no |

| 17 | 66 | m | no | 0 | no |

| 18 | 78 | f | no | 1 | no |

| 19 | 56 | m | no | 1 | no |

| 20 | 94 | m | no | 0 | no |

| 21 | 86 | f | no | 0 | no |

| 22 | 24 | m | no | 0 | no |

| 23 | 59 | m | no | 0 | no |

| 24 | 71 | f | no | 1 | no |

| 25 | 97 | f | no | 2 | no |

| 26 | 83 | m | no | 1 | no |

| 27 | 85 | f | no | 0 | no |

*All information was collected from the Huddinge Brain Bank at Karolinska Institute.

f = female; m = male.

Figure 1. Accumulation of Aβ40 and Aβ42 plaques in brain arterioles and microvessels of human AD patients.

(A) Immunohistological staining of the cortex of a representative AD patient with anti-Aβ40 or anti-Aβ42 specific antibodies. As a control, healthy control cortex from a non-AD patient was stained with the combination of anti-Aβ40 and anti-Aβ42 specific antibodies. Red arrowheads point to Aβ plaques accumulated in arterioles and blue arrows indicate non-vasculature-associated Aβ plaques. Bar = 50 μm. (B) Immunohistochemical double staining of the cortex of an AD patient or of the healthy control individual with anti-Aβ40 or anti-Aβ42 specific antibodies (in red) in combination with a mouse anti-human CD31 or α-SMA antibody (in green). Arrows point to double-stained (in yellow) vasculature-associated Aβ plaques.

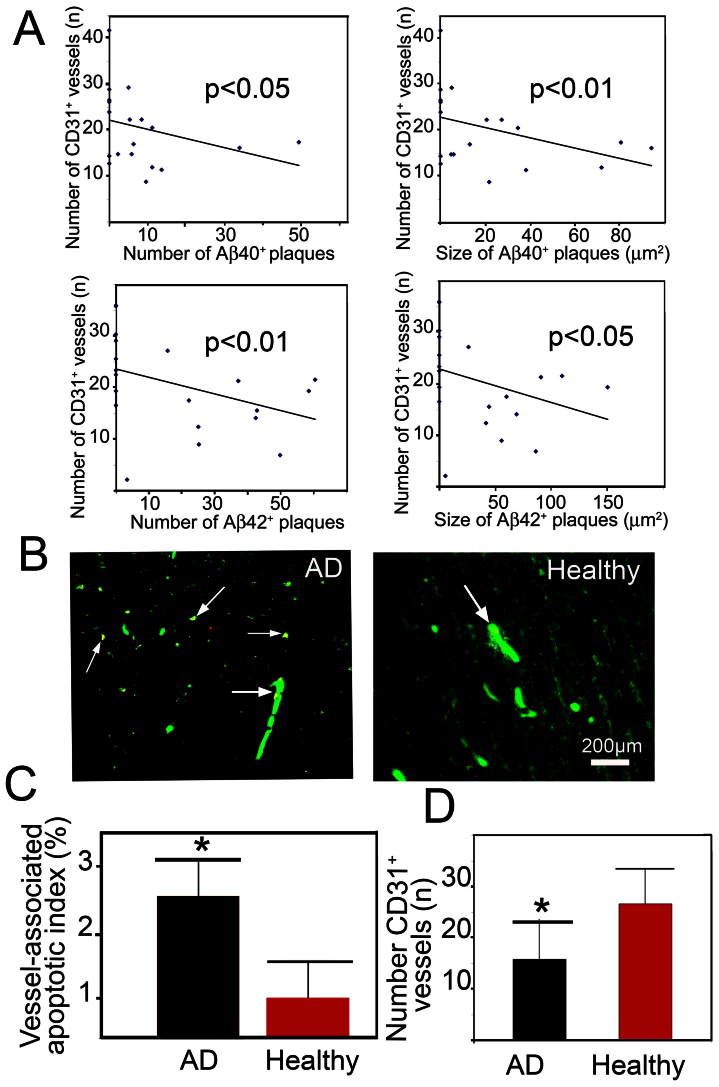

Reverse correlation of the density between blood vessels and amyloid plaques

To correlate vascular density with numbers of plaques (Aβ deposits positive stained for Aβ-40- and Aβ-42), the total number of CD31+ microvessels was associated with the total number of amyloid plaques used patients (3 images/patient). Intriguingly, a reverse correlation of the total number of CD31+ microvessels with the total number of amyloid plaques existed in both Aβ-40- and Aβ-42-stained AD samples (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the size of amyloid plaques was also reversely correlated with the total number of CD31+ microvessels. These results suggest that blood vessel-associated amyloid plaques might play a destructive role in maintenance of the integrity of brain vasculature.

Figure 2. Reverse correlation between Aβ plaques and vessel density.

(A) Correlation of the total vessel number in the brain cortex with size and number of Aβ40 or Aβ42 plaques. Brain samples from totally 15 AD patients and 12 non-AD individuals were used for correlation. (B) Double immunostaining of the cortex from an AD patient or from healthy control patients with an anti-CD31 (green) and TUNEL staining (red). Arrows indicate the vasculature-associated double positive apoptotic cells. Bar = 200 μm. (C) Quantification of CD31+ vessel-associated apoptotic index (n = 12–15 samples/group). (D) Quantification of the total number of CD31+ vessels in the cortex (n = 12–15 samples/group). * p < 0.05.

Elevated apoptotic vascular cells in the brain tissue of AD patients

To study the underlying mechanism by which amyloid plaques induced vessel regression, apoptotic cells in the brain tissue were detected using the TUNEL method24. CD31 and TUNEL double staining showed that a significant increased number of CD31+ vessels underwent cellular apoptosis relative to healthy controls (Fig. 2B). Quantification analysis showed that nearly 3% of the total CD31+ vessels underwent apoptosis, whereas only 1% of the apoptotic index existed in healthy controls (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the total number of CD31+ vessels was also significantly decreased in the brain tissue of AD patients as compared with healthy controls (Fig. 2D). These data show that increased vascular apoptosis is at least in part responsible for amyloid plaque-induced vessel regression in the brain tissue of the AD patients.

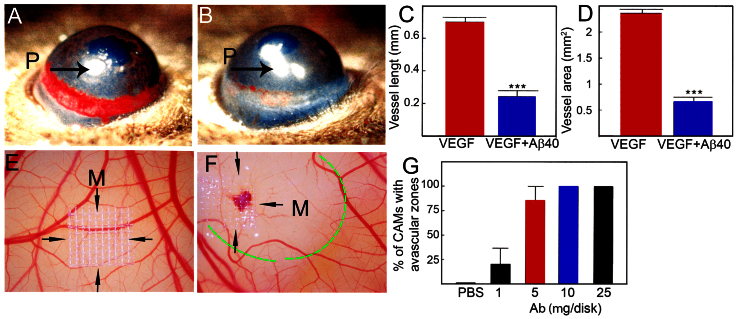

Aβ induces vascular regression

The increased level of vascular apoptotic index suggested that Aβ might induce vessel regression. To test this possibility, two in vivo angiogenesis models i.e., the mouse corneal angiogenesis model and the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model were used to determine vascular regressive effect of Aβ. In the mouse corneal angiogenesis model, implantation of Aβ (1–40) virtually completely prevented VEGF-induced vessel growth (Fig. 3 A–D), suggesting that VEGF-induced new blood vessel was abrogated by Aβ (1–40). Similarly, implantation of Aβ (1–40) onto the developing CAM in chick embryos led to significant regression of the existing and newly developed blood vessels by the formation of an avascular zone around the implanted mesh (Fig. 3E–G). These results show that Aβ displays significant vessel regression activity in vivo and thus correlates with significant decreases in total vessel density in the brain tissue of AD patients.

Figure 3. Mouse corneal and chick chorioallantoic membrane angiogenesis assays.

(A) Representative picture of mouse cornea implanted with VEGF165 pellet at day 7 after implantation. (n = 6 samples/group). (B) Representative picture of mouse cornea co-implanted with VEGF165 plus Aβ (1–40) (n = 5 samples/group). Arrows point to the position of the implanted pellets. (C) Quantification of corneal vessel length. (n = 11 samples/group). (D) Quantification of corneal vessel area. (n = 11 samples/group). (E) Representative picture of vehicle-implanted CAM. (F) Representative picture of Aβ (1–40)-implanted CAM. Arrows indicate the position of the implanted mesh. The dashed line encircles the avascular zone. (G) Quantification of numbers of CAMs with avascular zones. (n = 7–10 samples/group). *** p < 0.001.

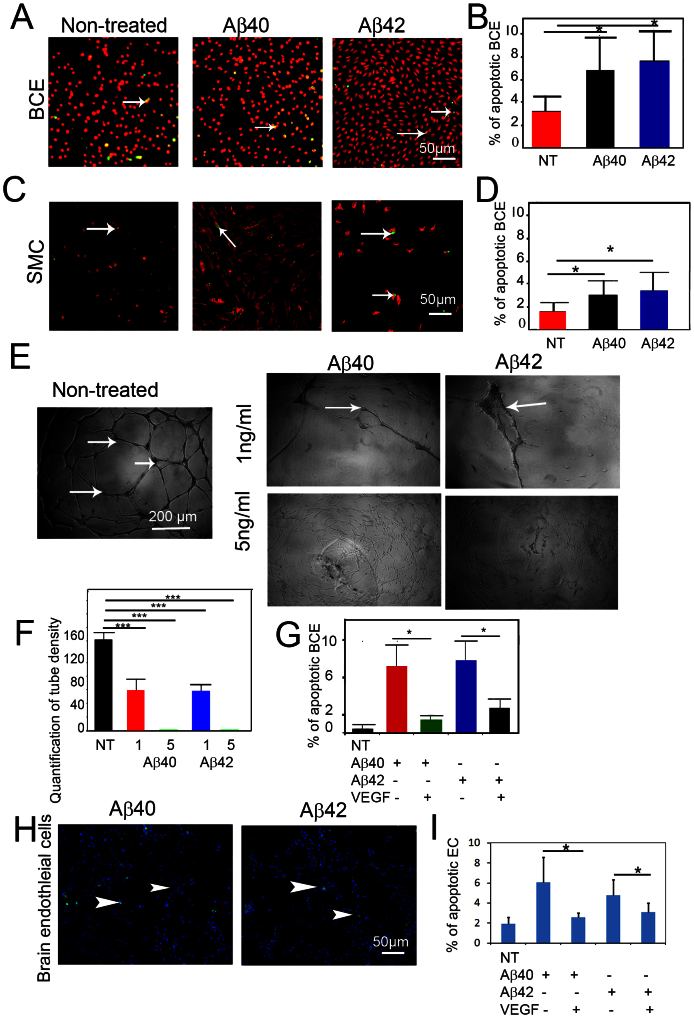

Aβ induces vascular cell apoptosis

To further study the vascular degenerative effect of Aβ, we treated isolated primary ECs and VSMCs with Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42). As expected, Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42) significantly induced apoptotic indexes of bovine capillary endothelial (BCE) cells and VSMCs (Fig. 4A–D). Moreover, Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42) inhibited VEGF induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) tube formation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4 E–G). Notably, Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42) at the concentration of 5 ng/ml almost completely abrogated HUVEC tubular formation. These findings demonstrate that Aβs exhibited potent apoptotic activity on ECs and VSMCs. To study if VEGF could counteract Aβ-induced vascular cell apoptosis, BCE cells were treated with Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42) in the presence or absence of VEGF. Interestingly, VEGF could significantly rescue Aβ-induced EC apoptosis, suggesting that VEGF acts as a survival factor for ECs. To extend these findings, mouse brain ECs grown on Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42)-coated plates were treated with VEGF, followed by apoptosis analysis of activate caspase 3. As expected, VEGF significantly protected EC from Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42)-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4H and I), strengthening our conclusion that VEGF is a survival factor for mouse brain EC.

Figure 4. Induction of endothelial cell apoptosis by Aβ peptides.

(A) Bovine capillary endothelial cells (BCEs) were treated with (1 ng/ml) of Aβ (1–40) or Aβ (1–42) for 48 h, followed by double staining with Propidium iodide and TUNEL. Arrows point to apoptotic cells. (B) Quantification of apoptotic index (n = 5 samples/group). (C) Mouse VSMCs were treated with (10 ng/ml) of Aβ (1–40) or Aβ (1–42) for 48 h, followed by double staining with propidium iodide and TUNEL. Arrows point to apoptotic cells. (D) Quantification of apoptotic index (n = 5 samples/group). (E) In vitro Matrigel endothelial cell tube assay in the presence of 1 ng/ml or 5 ng/ml of Aβ (1–40) or Aβ (1–42), or absence of Aβ peptides. (F) Quantification of tube density (n = 13–17 samples/group). (G) Quantification of the apoptotic index of BCE cells pre-exposed to Aβ (1–40)- or Aβ (1–42)-coated plates, followed by VEGF stimulation (n = 5 samples/group). * p < 0.05. *** p < 0.001. (H) Expression of caspase 3 in brain ECs. (I) Quantification of the apoptotic index of mouse brain endothelial cells pre-exposed to Aβ (1–40)- or Aβ (1–42)-coated plates, followed by VEGF stimulation. Bar = 50 μm.

Accumulation of Aβ plaques in brain arterioles in a mouse AD model

To recapitulate clinical relevance in a mouse AD model (CRND8), we investigated Aβ plaques in a transgenic mouse AD model, which carries double mutations in 695 amino acid isoform of the amyloid precursor protein (APP)25. This is a relatively aggressive AD model and transgenic mice begin to develop obvious memory impairment at the age around week 15 after birth. Histological examination of the mouse brain at week 18 revealed apparent Aβ plaques in AD mice but not in control mice at the same age (Fig. 5A). Similar to human AD patients, a significant number of Aβ plaques were found to be associated with arterioles and microvessels in the brain of CRND8 mice (Fig. 5B). In contrast, no Aβ immunostained plaque deposits were detected in non transgenic animals (Fig. 5C). These results show that Aβ plaques are accumulated in arterioles and microvessels in the brain of AD mice and thus parallel our findings in human AD patients.

Figure 5. Vascular location of Aβ plaques in brain of CRND8 transgenic mice.

(A) CRND8 transgenic or WT mice at the age of 18 weeks were sacrificed for immunostaining with anti-Aβ40 or anti-Aβ42 specific antibodies. Arrows point to Aβ plaques. Size bar = 0.2 mm. (B) Immunohistochemical double staining of the cortex of CRND8 transgenic or WT mice with anti-Aβ40 or anti-Aβ42 specific antibodies in combination with an anti-mouse CD31 or with a mouse anti-human α-SMA antibody. Arrows point to vasculature-associated Aβ plaques.

Accumulation of Aβ plaques in brain arterioles in a mouse AD model

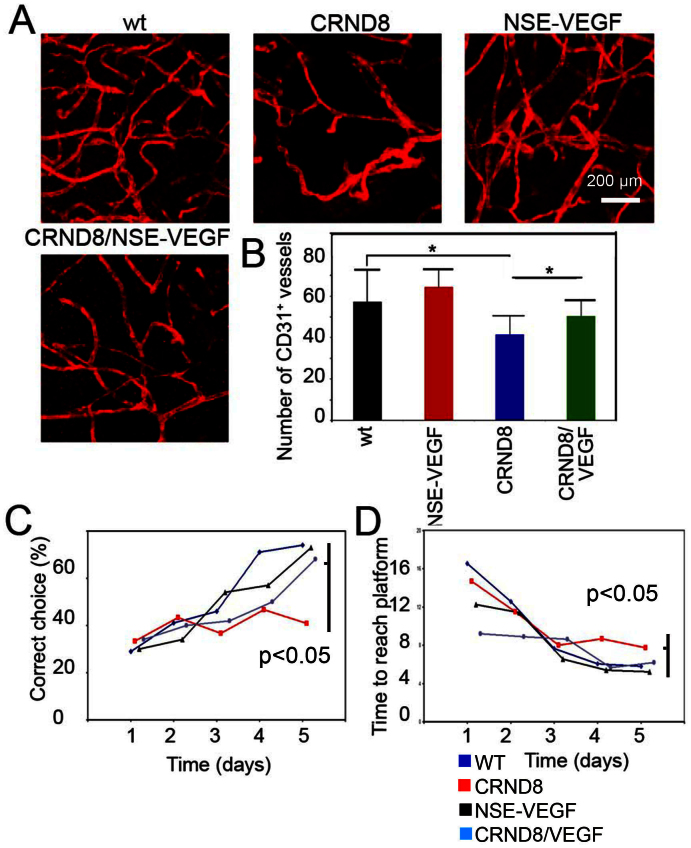

To study functional consequences of vascular impairment by Aβ, CRND8 APP695 mice and the neuron-specific enolase (NSE)-VEGF165 transgenic mice were used for assessing memory behaviors1,26. Vascular density in the cerebral cortex of CRND8 AD mice was significantly decreased and, supporting the vascular destructive role of Aβ in the brain tissue (Fig. 6A and B). Although vascular density in the cerebral cortex of NSE-VEGF165 transgenic mice was not significantly altered, double transgenic mice showed that VEGF could partially rescue vascular loss in the region of cerebral cortex (Fig. 6B). These data support our in vitro findings that VEGF significantly prevents Aβ-induced endothelial cell death and the notion that VEGF acts as a vascular survival factor in CNS.

Figure 6. Vascular and functional rescue of CRND8 transgenic mice by overexpression of VEGF.

(A) Cortex vasculature of WT, CRND8, (NSE)-VEGF and CRND8/(NSE)-VEGF mice stained for CD31 expression. Bar = 0.2 mm. (B) Quantification of vessel density (n = 5 samples/group). (C) Percentage of mice that made correct choice during water T-Maze test (n = 6–12 samples/group). (D) Time to reach platform test (n = 6–12 samples/group). * p < 0.05.

Functional rescue of memory behaviors of AD mice by VEGF

To study if VEGF could functionally rescue the impaired memory of CRND8 AD mice, we performed a water T-maze test to analyze learning including acquisition of spatial memory. As expected, CRND8 mice showed significantly impaired memory behaviors compared with c57/b6 and NSE-VEGF165 mice (n = 7–12/group). Respectively, less than 40% CRND8 AD mice made correct choices after 5 days compared to over 60% in c57/b6 and NSE-VEGF165 groups (Fig. 6C). Intriguingly, double transgenic mice showed significant improvement of memory behaviors relative to CRND8 AD mice. Additionally, these results were also confirmed also by measurement of time to reach platform where double transgenic mice VEGF also improved upon the latency of CRND8 mice to reach platform (Fig. 6D). These findings demonstrate that VEGF expressed in CNS could functionally rescue memory behaviors of AD mice with a mechanism involving modulation of the vascular system, as discussed below.

Discussion

Recent evidence shows that pathological alterations of the cerebrovasculature are the early features of AD, which include vascular structural changes, accumulation of atherosclerotic plaques and impairments of hemodynamic responses1. Consistent with these vascular abnormalities, substantial Aβ deposition has been found to accumulate within the arterial blood vessels in AD patients. These findings suggest that the cerebrovasculature is probably the primary target of Aβ peptid in AD patients27. In the present study, we show that significant amounts of Aβ plaques are deposited in both large arterioles and microvessels of the brain tissues of TgCRND8 APP transgenic mice and of human AD patients.

In both in vitro and in vivo experimental settings, we provide compelling evidence showing that Aβ peptides exhibited vascular regression activity by a mechanism of inducing endothelial cell apoptosis. In support of this notion, vascular density in the AD transgenic mice is significantly decreased, suggesting Aβ plaques playing a destructive role in maintenance of cebrebrovascular integrity. Similar to the vasculature elsewhere in the body, maintenance of the vascular integrity and hemodynamic functions requires vascular survival signals, which are usually triggered by a distinct set of vascular survival factors11,28. VEGF is known to act as a potent vascular survival factor to prevent vascular endothelial cells death induced by various cellular apoptotic signals. Several recent studies show that VEGF displays neurotrophic activity by acting directly on nerve cells. These findings demonstrate that VEGF plays a dual role in maintenance of the physiological functions of the CNS. In the present study, we show that Aβ peptides exhibit antagonistic activity against VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular survival effects. Additionally, we show that Aβ peptides potently induce cellular apoptosis of VSMCs, which are crucial for maintenance of vascular integrity and physiological functions of arterial networks. The fact that Aβ peptides preferentially accumulate in cerebral arterioles suggests that these pathological peptides may significantly induce the loss of VSMCs and endothelial cells in arterial walls. These findings, at least in part, explain the mechanisms underlying vascular destructive activity of Aβ peptides. We should emphasize that we have not observed any vascular functional differences between Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42) in our endothelial cell assay system. However, it is possible that these two forms of amyloid peptides may possess different functional properties on the vasculature during Alzheimer's disease development. The distinctive vascular functions of Aβ (1–40) and Aβ (1–42) warrant further investigation.

These mechanistic findings have also provided an exciting opportunity of therapeutic interventions by shifting the balance favoring angiogenic signals. To do so, we have undertaken a genetic approach to overexpress VEGF in the brain tissue. This genetic approach seems to be therapeutic advantageous relative to systemic protein delivery because VEGF usually has a relative short half-life and could induce global vascular changes other than CNS29. The finding that NSE-VEGF- CRND8 double transgenic mice could significantly improve the integrity of cerebrovasculature and memory behaviors implies that delivery of proangiogenic factors to AD patients may offer an exciting opportunity of novel therapy. By extrapolation, combinations of proangiogenic molecules with existing AD drugs may further improve therapeutic efficacy. These exciting opportunities warrant further investigation.

Taken together, we present data that have shed new light of molecular mechanisms underlying the vascular role in development of AD and have conceptual implication of delivery of proangiogenic factors for the treatment of AD.

Methods

Human samples

Human autopsy brain samples from 15 (12 female, 3 male, age 79.7 ± 8.4) AD patients and 12 healthy individuals (5 female, 7 male, age 70.8 ± 20), were obtained from the Huddinge Brain Bank at Karolinska Institute22. The use and handling of human samples were carried out in accordance with, and by the laws and permissions of Stockholm Ethical Committee (Ethical approval 606/03). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects for donation of samples to Huddinge Brain Bank at Karolinska Insitute.

Animals

Female C57Bl/6 mice were anesthetized with Isoflurane (Abbott Scandinavia) before all procedures and followed up to 6–8 weeks. TgCRND8 (B6/C3H) mice were obtained from the Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases at the University of Toronto, Canada. This transgenic line carries a point mutation in the human amyloid precursor protein gene and shows age-related increases in Aβ plaque deposition and Morris maze impairments25. In the neuron-specific enolase (NSE)-VEGF165 mice, expression of human VEGF165 was driven by the rat NSE promoter26,30. CRND8 and (NSE)-VEGF165 were crossed in the C57Bl/6 background. Mice were sacrificed by exposure to a lethal dose of CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Animal care and use committee of the North Stockholm Animal Board (Stockholm, Sweden). Animal research was done in adherence to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay

The CAM assay was performed as described31. Briefly, three-day-old chicken embryos with intact yolks cracked from White Leghorn eggs (OVA Production, Sörgården, Sweden) were carefully placed in each of plastic Petri dishes (20 × 100 mm). At 48 h after incubation in 4% CO2/96% air at 37°C, methylcellulose discs (4 × 4 mm) of containing Aβ peptides were implanted on the CAMs of developing embryos (disc/embryo). After 48–72 h of incubation, embryos and CAMs were examined under a stereoscope for the formation of avascular zones in the field of the implanted discs 7–10 embryos, 1–50 μg/mesh of Aβ (1–42).

Mouse corneal angiogenesis model

The mouse corneal assay was performed as described32. Human VEGF165 (160 ng) alone or plus Aβ (1–40) (5 μg) in each micropellet made from sucrose aluminum sulfate (Bukh Meditec, Copenhagen, Denmark) coated with hydron polymer type NCC (IFN Sciences, New Brunswick, NJ) was implanted into each corneal micropoket of C57Bl/6 mice. Corneal neovascularization was examined at day 7 after micropellet implantation (n = 5–6/group).

In vitro cell culture

VSMCs were isolated from the aortic media of 6–10-week-old mice C57Bl/6 by collagenase digestion as previously described33. After rinsing, cells were suspended in Ham's medium F-12 supplemented with 10 mM Hepes and Tes (pH 7.3), 50 mg/ml of L-ascorbic acid, 50 mg/ml of streptomycin, 50 IU/ml of penicillin, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (F-12/0.1% BSA; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). The cells were resuspended in F-12/0.1% BSA, seeded in matrix-coated plastic dishes or on glass coverslips, and grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Cells were changed with fresh medium every day.

Primary bovine capillary endothelial cells (BCE) were isolated and cultured as previously described34 VSMC and BCE cells were incubated with 1 ng/ml Aβ (1–40) or Aβ (1–42) (Biosource) for 48 h in presence of 10% FCS. Apoptotic cells were by TUNEL assay. In another set of experiment, Aβ (1–40) or Aβ (1–42) was used to coat culture coverslips prior seeding BCE cells, which were further cultured with DMEM containing 0.1% BSA in the presence or absence of VEGF165 (10 ng/ml) for 48 h.

TUNEL

TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling) assays were performed according to our previously published methods and the manufacturer's instructions (the TUNEL kit, Boehringer Mannheim, Germany).

Immunohistochemistry

Brain samples were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Paraffin-embedded samples were prepared according to the standard method33. Tissue sections were re-hydrated in xylene-graded ethanol, and immersed in water for 5 min followed by treatment with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide and 70% methanol for 20 min. For staining, reagents from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA) include Vectastain Elite ABC kit, 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) peroxidase substrate kit, unmasking solution, hematoxylin, normal goat serum, a biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody, a biotinylated anti-mouse antibody, normal rabbit immunoglobulins, and normal mouse immunoglobulins. A mouse anti-α-smooth muscle-actin antibody (Dako), a mouse anti-human CD31 (Dako), a rat anti-mouse CD31 (BD bioscience) monoclonal antibody, rabbit anti-caspase 3 (Abcam), and rabbit anti-Aβ 40 and anti-Aβ 42 antibodies were used our study. Epitopes were exposed by boiling in unmasking solution and samples were blocked with 2% goat serum from (Dako) for 30 min. The samples were incubated with primary antibodies PBS for 15 h at 4°C. The samples were further incubated with secondary antibodies for 30 min, treated with avidin–biotin amplification reagents for 30 min, and incubated with DAB and hydrogen peroxide for 5 minutes. Certain samples were counterstained with hematoxylin (2–5 min). The fluorescent labeled antibodies were used for immunostaining and propidium iodide was used for counterstaining. Positive signals were analyzed under a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope.

Whole-mount staining

Freshly dissected mouse brain tissues were used for whole-mount staining and detailed procedures were previously described32. A rat anti-mouse CD31(1:200, BD bioscience) were used for immunohistochemical analysis. Positive signals were analyzed using a confocal microscope (Zeiss). Microvessel density was quantified 3 fields from 6–12 animals.

Water T maze test

The water T maze was designed in such a way that a T-arm maze placed in a large circular black pool of 120 cm diameter × 50 cm height, filled with water (30 cm in depth) at 24 ± 2°C temperature35. The entire pool-T maze facility was placed in a darkroom. The T-maze was made of a start arm (47 × 10 cm) and two identical goal arms (35 × 10 cm) with a platform at the end of each goal arm. In each individual trial, each individual mouse performed a sample-run followed by a choice-run. During the sample-run, mice were directed either left or right in a randomized sequence in the presence of a door at the starting point of one of the goal arms. Mice reached to the platform to escape from the necessity of swimming. The time interval between the sample- and the choice-run was approximately 15 sec. The same starting position was used for each trial. Mice were given a maximal time of 60 sec (cut-off time) to find the platform and were allowed to stay for 30 sec. Each block was composed of totally ten trials, conducted in five consecutive days with ten trials per day. The trial was given for 5 consecutive days in order to train mice in water maze. The time and choice of platform were recorded for each animal. All results were analyzed with ANOVA.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the standard 2-tailed Students t test on Microsoft Excel 2003. For the comparison of multiple samples we used ANOVA (Statistica 10, Statsoft) p < 0.05; p < 0.01; and p < 0.001 were deemed as significant, highly significant, and extremely significant, respectively.

Author Contributions

Y.C. wrote the main manuscript text. P.R., Y.X., N.B., D.R., B.W. contributed to figures 1–2. R.C. prepared figure 3, P.R., Y.X., D.R., H.H.M., D.W., B.W. contributed to figures 4–6. N.B., D.R., B.W. contributed to table 1. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Y.C.'s laboratory is supported by research grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Karolinska Institute Foundation, the Karolinska Institute distinguished professor award, the Torsten Söderbergs foundation, Söderbergs stiftelse, the Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (CMM-Tianjin, No. 09ZCZDSF04400) for international collaboration between Tianjin Medical University and Karolinska Institutet, ImClone Systems Inc./EliLilly, the European Union Integrated Project of Metoxia (Project no. 222741), and the European Research Council (ERC) advanced grant ANGIOFAT (Project no 250021). Additional grants were obtained from the Karolinska Institute (P.R.), the Belven foundation (D.R.), the Foundation for Geriatric Research (D.R.), the Stones Foundation (P.R.), the Swedish Research Council 523-2012-2291 (D.R.), the Foundation of Gamla Tjänarinnor (P.R.), the Alzheimer Foundation (P.R.), and the Swedish Society of Medicine (P.R.). P.R. is supported by Swedish Cancer Foundation and the European Union, FP7 (IDEA).

References

- Beckmann N. et al. Age-dependent cerebrovascular abnormalities and blood flow disturbances in APP23 mice modeling Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 23, 8453–8459 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz W. Studies on Pathology of the Brain Vessels II: The Glandular Degeneration of Brain Arteries and Capillaries. Z Neurol Psychiatr. 26, 694–715 (1938). [Google Scholar]

- Vinters H. V. & Gilbert J. J. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: incidence and complications in the aging brain. II. The distribution of amyloid vascular changes. Stroke 14, 924–928 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandybur T. I. The incidence of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 25, 120–126 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H. et al. Blood-neural barrier: intercellular communication at glio-vascular interface. J Biochem Mol Biol 39, 339–345 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meletis K. & Frisen J. Have the bloody cells gone to our heads? J Cell Biol 155, 699–702 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezey E., Chandross K. J., Harta G., Maki R. A. & McKercher S. R. Turning blood into brain: cells bearing neuronal antigens generated in vivo from bone marrow. Science 290, 1779–1782 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. & Henzel W. J. Pituitary follicular cells secrete a novel heparin-binding growth factor specific for vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 161, 851–858 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gospodarowicz D., Bialecki H. & Greenburg G. Purification of the fibroblast growth factor activity from bovine brain. J Biol Chem 253, 3736–3743 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo H. et al. Enhanced adult neurogenesis and angiogenesis and altered affective behaviors in mice overexpressing vascular endothelial growth factor 120. J Neurosci 28, 14522–14536 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak H. F. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: a critical cytokine in tumor angiogenesis and a potential target for diagnosis and therapy. J Clin Oncol 20, 4368–4380 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y. Positive and negative modulation of angiogenesis by VEGFR1 ligands. Sci Signal 2, re1 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. et al. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 380, 439–442 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. et al. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature 380, 435–439 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucci S., Mazzarelli P., Missiroli F., Regine F. & Ricci F. Neuroprotection: VEGF, IL-6, and clusterin: the dark side of the moon. Prog Brain Res 173, 555–573 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnert F. et al. Soluble receptor-mediated selective inhibition of VEGFR and PDGFRbeta signaling during physiologic and tumor angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 10185–10190 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R. Jr VEGF receptor protein-tyrosine kinases: structure and regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 375, 287–291 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soker S. Neuropilin in the midst of cell migration and retraction. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 33, 433–437 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier-Lavigne M. & Goodman C. S. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science 274, 1123–1133 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. & Tessier-Lavigne M. Common mechanisms of nerve and blood vessel wiring. Nature 436, 193–200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier-Lavigne M., Placzek M., Lumsden A. G., Dodd J. & Jessell T. M. Chemotropic guidance of developing axons in the mammalian central nervous system. Nature 336, 775–778 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Religa D. et al. Elevated cortical zinc in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 67, 69–75 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H. & Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta neuropathologica 82, 239–259 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Religa P. et al. Allogenic immune response promotes the accumulation of host-derived smooth muscle cells in transplant arteriosclerosis. Cardiovascular research 65, 535–545, 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.011 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde L. A. et al. Age-progressing cognitive impairments and neuropathology in transgenic CRND8 mice. Behav Brain Res 160, 344–355 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. VEGF overexpression induces post-ischaemic neuroprotection, but facilitates haemodynamic steal phenomena. Brain 128, 52–63 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinters H. V. et al. Microvasculature in brain biopsy specimens from patients with Alzheimer's disease: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct Pathol 18, 333–348 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen T. M., Moss A. J. & Brindle N. P. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietins in neurovascular regeneration and protection following stroke. Curr Neurovasc Res 5, 236–245 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y. et al. Anti-VEGF agents confer survival advantages to tumor-bearing mice by improving cancer-associated systemic syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 18513–18518, 10.1073/pnas.0807967105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J., Gehrig M., Kuschinsky W. & Marti H. H. Massive inborn angiogenesis in the brain scarcely raises cerebral blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 24, 849–859 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R. et al. Suppression of angiogenesis and tumor growth by the inhibitor K1-5 generated by plasmin-mediated proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 5728–5733 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Religa P. et al. Presence of bone marrow-derived circulating progenitor endothelial cells in the newly formed lymphatic vessels. Blood 106, 4184-4190, 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0226 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Religa P. et al. Host-derived smooth muscle cells accumulate in cardiac allografts: role of inflammation and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1. PloS one 4, e4187, 10.1371/journal.pone.0004187 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veitonmaki N. et al. Immortalization of bovine capillary endothelial cells by hTERT alone involves inactivation of endogenous p16INK4A/pRb. Faseb J 17, 764–766 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bakri N. K. et al. Effects of estrogen and progesterone treatment on rat hippocampal NMDA receptors: relationship to Morris water maze performance. J Cell Mol Med 8, 537–544 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]