Abstract

We determined the composition of ~30-m.y.-old solutions extracted from fluid inclusions in one of the world's largest and richest silver ore deposits at Fresnillo, Mexico. Silver concentrations average 14 ppm and have a maximum of 27 ppm. The highest silver, lead and zinc concentrations correlate with salinity, consistent with transport by chloro-complexes and confirming the importance of brines in ore formation. The temporal distribution of these fluids within the veins suggests mineralization occurred episodically when they were injected into a fracture system dominated by low salinity, metal-poor fluids. Mass balance shows that a modest volume of brine, most likely of magmatic origin, is sufficient to supply the metal found in large Mexican silver deposits. The results suggest that ancient epithermal ore-forming events may involve fluid packets not captured in modern geothermal sampling and that giant ore deposits can form rapidly from small volumes of metal-rich fluid.

Epithermal precious metal deposits, regarded as the exhumed product of fossil geothermal systems1, host ~6% of the world's gold resources and ~17% of the silver2. Mexico has a remarkable endowment of silver, mostly in epithermal vein deposits, and has produced more than 25% of the world's total of this metal3. Furthermore, these deposits are unique in terms of their unusually high silver grades (500 to 2000 g/t Ag) and elevated base metal tenor. This poses two key questions: what controls the origin and spatial distribution of giant ore deposits such as these in general, and why is the Mexican crust so anomalous with regard to silver and base metals in particular?

One key dataset required to address these issues is the metal content of the ore-forming fluids. In the past decade, compositions of hydrothermal fluids have been increasingly well documented through two approaches. First, new sampling technology has enabled precious metal analyses of modern deep, hot, geothermal fluids4,5 which represent possible analogues for ancient epithermal ore solutions. These data have been used to suggest that the world class Ladolam gold deposit in Papua New Guinea, could have formed from the steady flux of solutions containing 15 ppb gold in just 50 ky4.

Recent analytical developments have made possible the second approach which involves the analysis of trace elements in individual fluid inclusions – fossil solutions trapped during ancient mineral precipitation6 – by laser ablation inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS; e.g.7,8). This allows direct measurement of paleofluid chemistry but is hindered by the difficulty in proving a temporal link between the inclusions analyzed and ore-forming events. Data from this technique highlight an apparent disconnect between the two approaches. The measurement of orders of magnitude higher gold concentrations in fluid inclusions than observed in modern geothermal fluids9 suggests that ore-forming events may involve fluid packets that are not captured in modern sampling. If true, it implies that orebodies could form in even shorter time periods than suggested by Simmons and Brown4. Whichever is correct, the results from these studies challenge long-held views on rates of ore formation and have sparked a vigorous debate surrounding the nature of ore fluids and ore-forming processes in precious metal deposits.

Here, we report the first data on the silver and base metal content of fluids involved in the formation of a world class epithermal silver deposit, acquired by LA-ICP-MS analysis of primary fluid inclusions from the Fresnillo district, Mexico. We argue that episodic and very short-lived pulses of rather modest volumes of unusually silver-rich magmatic brine into a low salinity geothermal circulation system were responsible for high grade ore formation. This supports an emerging view that large hydrothermal ore deposits may form very rapidly in rare, cataclysmic events that perturb more stable fluid circulation patterns.

The epithermal deposits of northern Mexico have been well studied and provide an excellent opportunity to investigate the nature of precious metal ore fluids. The deposits are divisible into two overlapping metallogenic belts containing Ag-Au and Ag-Pb-Zn ores that extend for over 1,000 km along a northwest-southeast trend1,10. Some of the deposits are middle to late Eocene age, but most formed in the Oligocene to Miocene10, contemporaneous with the onset of the Sierra Madre Occidental ignimbrite event when felsic volcanism was especially intense and widespread. Remnant outcrops from this period largely comprise pyroclastic deposits which extend over a huge area of ~296,000 km2 and have an average thickness of 1 km11.

The Fresnillo district contains a resource of >48,000 t of silver, making it the largest silver deposit in Mexico and the second largest in the world1,3. Mineralization was discovered on Cerro Proaño in the center of the district in 1553 and mining of the silver oxides in near-surface stockwork took place from 1554 until 1942. The ores exploited more recently comprise deep-formed Cu-Zn-Pb-Ag replacement bodies and shallow-formed Ag-Pb-Zn epithermal veins12. From 1985 to 2005, the resource in the district more than doubled in size due to discovery of new blind veins3 and mineralization is now known to occur over >50 km2.

The Fresnillo ores are hosted by deformed Mesozoic marine sedimentary rocks interleaved with mafic pillow basalts that are unconformably overlain by an Eocene-Oligocene sequence of tilted and flat lying welded pyroclastic deposits13,14. Ore formation occurred in multiple mineralizing events between 32 and 29 Ma15,16. The quartz samples used in our study were collected from the Cerro Proaño vein stockwork in the high grade center of the Fresnillo district17. These were selected for analysis because of the rarity of material from epithermal veins that contains abundant large, well-preserved, and unambiguously primary fluid inclusions amenable to trace element determination. In addition, these samples host fluid inclusions with relatively high homogenization temperatures (from 270 to >300°C17), suggesting they formed from deep ore-forming solutions. This offers the opportunity to sample pregnant ore fluids, potentially trapped prior to significant precipitation of metals due to cooling and/or depressurization on ascent, e.g.9.

Results

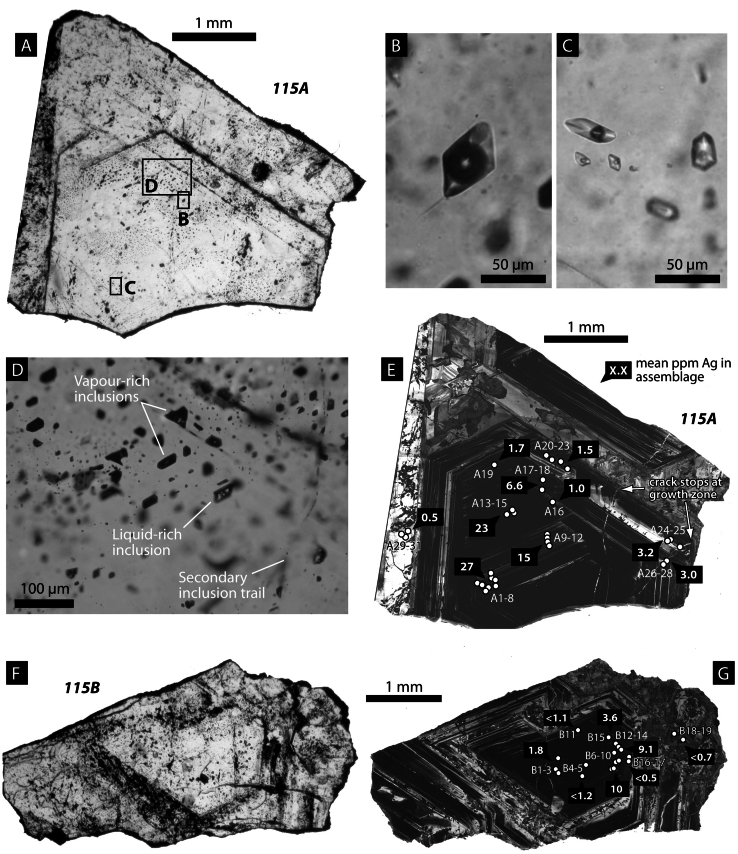

Liquid-vapor inclusions (75–80 volume% liquid), averaging 20 × 35 μm in size, occur frequently in growth zones and occasionally along fracture trails (Fig. 1). The former typically display negative crystal forms (Figs. 1B, 1C) and are clearly of primary origin. These commonly coexist with vapor-rich inclusions (Fig. 1D) – good evidence for trapping of boiling fluids during crystal growth.

Figure 1. Photomicrographs illustrating features of the quartz samples and fluid inclusions studied.

(A) Transmitted light microscope image of growth-zoned crystal (sample 115A). Boxes show locations of Figs. 1B, 1C and 1D. (B) and (C) Examples of typical liquid + vapor fluid inclusions. (D) Field of view illustrating coexisting euhedral vapor and liquid-rich inclusions indicative of trapping of a boiling fluid. (E) SEM-cathodoluminescence image of sample shown in Fig. 1A illustrating complex growth zoning and showing locations of inclusions analysed. Fluid inclusion identification numbers within each fluid inclusion assemblage are shown and each assemblage is labelled with the mean silver content of the fluid trapped. (F) Transmitted light microscope image of growth-zoned crystal (sample 115B). (G) SEM-cathodoluminescence image of sample 115B illustrating complex growth zoning, similar to 115A, and showing locations and mean silver content of inclusion assemblages analysed.

SEM-CL petrography reveals complex zoning patterns. These are characterized by generally dully-luminescent crystal cores that contain ultra-fine scale oscillatory zoning successively overgrown by banded quartz, more brightly luminescent sector-zoned quartz with patchy dissolution textures, and a late stage of brightly luminescent, mottled quartz (Figs. 1E, 1G). Cracks that cut the early crystal cores but are overgrown by later growth zones are filled with brightly-luminescent quartz (Fig. 1E) and contain pseudosecondary fluid inclusions. Closely spaced fluid inclusions were assigned to eighteen individual fluid inclusion assemblages within which inclusions were likely to have been trapped at, or close to, the same time18. On the basis of the position of these assemblages within the growth zones or crosscutting fractures identified by SEM-CL, these were placed into an inferred time sequence of trapping in each sample. It should be noted that there is some ambiguity in this temporal assignment because of the complex growth zone structure in three dimensions and the difficulty in correlating growth zones on the finest scales at which they can be resolved. This is particularly problematic when attempting to correlate from one sample to another.

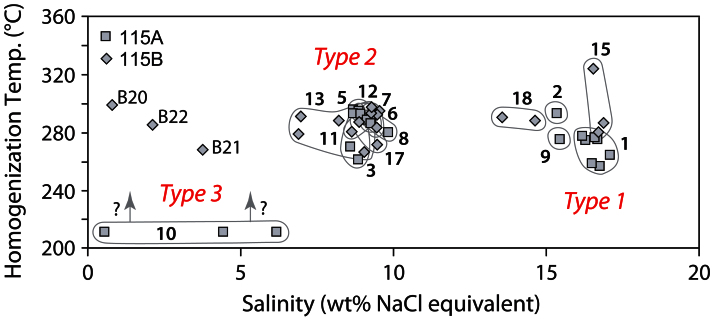

Microthermometric data define three distinct homogenization temperature-salinity groupings (Fig. 2) that appear to correspond broadly to the oscillatory zoned crystal cores (fluid type 1; 13.5–17.1 wt% NaCl equivalent), oscillatory zoned crystal cores and zoned overgrowths (type 2; 6.9–10.6 wt%) and the late, bright quartz (type 3; 0.6–6.2 wt%). These groups are consistent with previous results interpreted to reflect three stages of trapping of over-pressured fluids (~90 bar at paleodepths of 300–460 m17). Three inclusions trapped in a pseudosecondary crack that cuts the first two growth stages described above (Fig. 1; inclusions A13–15) also contains saline inclusions of type 1 indicating a later pulse of high salinity fluid.

Figure 2. Homogenization temperatures of fluid inclusions plotted as a function of fluid salinity.

Three fluid salinity groups (types 1, 2 and 3) are clearly defined. Individual fluid inclusion assemblages are numbered. Results from two samples, 115A and 115B, reproduce the same pattern providing confidence in the observed trends. Three type 3 inclusions did not have homogenization temperature measurements; these are plotted along the bottom axis.

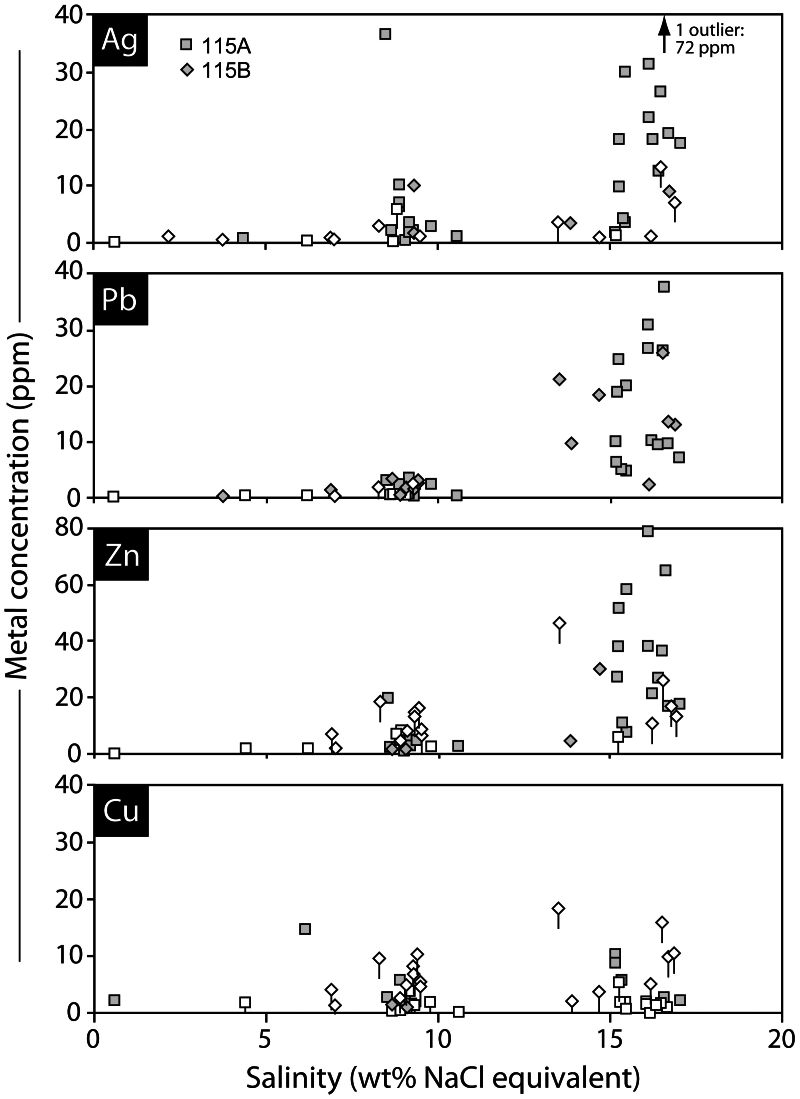

LA-ICP-MS analyses (Fig. 3; Table 1) detected Ag in 30 of 50 inclusions measured, with typical detection limits of 0.4–6 ppm. Averaging data gave a maximum of 27 ppm Ag in assemblage 1 and an overall mean across all assemblages of 14 ppm. Silver concentrations are highest in the early, higher salinity inclusions (Figs. 1, 3) but significant variation within each of the three salinity groups is observed. Silver concentrations correlate with Zn (type 1 fluids r2 = 0.54; type 2 fluids r2 = 0.86), Pb (type 1 fluids r2 = 0.66) and Ba (type 1 fluids r2 = 0.48), but not with Cu or Sb. Gold was not detected despite detection limits as low as 0.1 ppm in some inclusions.

Figure 3. Metal content of individual fluid inclusions plotted as a function of fluid salinity.

Three fluid salinity groups (types 1, 2 and 3) are clearly defined that have markedly different metal budgets. Results from two samples, 115A and 115B, reproduce the same pattern providing confidence in the observed trends. Open symbols with ticks indicate the detection limit for analyses below the limit of detection.

Table 1. Chemical composition of epithermal silver ore fluids.

| Assemblage | N* | Sal.† | Th§ | Li | Mg | Cl | K | Ca | Mn | Cu | Zn | Sr | Ag | Sb | Ba | Pb | Bi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 16.5 | 271 | 600 | 43 | 96280 | 28590 | 50250 | 810 | 2.2 | 38 | 400 | 27 | 14 | 33 | 20 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 4 | 15.4 | 294 | 740 | <38 | 93350 | 18760 | 41930 | 700 | <0.5 | 39 | 340 | 15 | 16 | 32 | 17 | <0.1 |

| 3 | 3 | 8.8 | 275 | 540 | <37 | 53110 | 9040 | 24480 | 410 | 1.7 | 14 | 160 | 23 | 8.3 | 0.6 | 2.0 | <0.1 |

| 4 | 1 | 10.6 | N.D.# | 810 | <13 | 64150 | 14010 | 30390 | 350 | <0.2 | 2.6 | 240 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | <0.1 |

| 5 | 2 | 8.9 | 296 | 460 | <17 | 54180 | 19370 | 17060 | 250 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 180 | 6.6 | 32 | 23 | 1.7 | <0.1 |

| 6 | 1 | 9.2 | 287 | 240 | 34 | 55760 | 18600 | 9210 | 3580 | <3.6 | 4.8 | 180 | 1.7 | 70 | 21 | 1.0 | 1.4 |

| 7 | 4 | 9.0 | 294 | 310 | 6.2 | 54170 | 15610 | 18600 | 370 | <0.2 | 2.7 | 190 | 1.5 | 9.4 | 22 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| 8 | 2 | 9.5 | 286 | 600 | <59 | 57690 | 2270 | 12960 | 79 | <1.6 | 2.8 | 110 | 3.2 | 54 | 5.2 | 3.0 | <0.1 |

| 9 | 3 | 15.3 | 276 | 650 | <24 | 92560 | 6000 | 36980 | 310 | 7.9 | 19 | 390 | 3.0 | 48 | 12 | 7.2 | <0.3 |

| 10 | 3 | 3.7 | N.D.# | 130 | <2.5 | 22640 | 1620 | 1280 | <0.7 | 8.2 | <0.1 | 17 | 0.5 | 45 | 1.2 | <0.03 | <0.1 |

| 11 | 3 | 9.0 | 288 | 330 | 72 | 54700 | 5890 | 13540 | 160 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 64 | 1.8 | 8.1 | 0.7 | 2.4 | <0.1 |

| 12 | 2 | 9.5 | 289 | 280 | <150 | 57320 | 3900 | 10630 | 310 | <4.6 | <6.1 | 50 | <1.2 | 11 | <1.6 | 3.1 | <0.5 |

| 13 | 5 | 8.1 | 285 | 400 | 56 | 49230 | 4270 | 12360 | 150 | <1.3 | <2.1 | 80 | 10 | 11 | 0.4 | 1.6 | <0.1 |

| 14 | 1 | 16.2 | N.D.# | 290 | <210 | 98000 | 3490 | 18760 | 290 | <5.1 | <11 | 100 | <1.1 | 3.9 | 5.4 | 2.5 | <0.2 |

| 15 | 3 | 16.7 | 297 | 750 | <220 | 101360 | 7450 | 28260 | 450 | <9.7 | <13 | 260 | 9.1 | 27 | 13 | 18 | <0.5 |

| 16 | 1 | 13.9 | N.D.# | 470 | <58 | 84130 | 6150 | 42540 | 460 | <2.1 | 4.7 | 220 | 3.6 | 26 | 8.7 | 9.7 | <0.3 |

| 17 | 2 | 9.2 | 280 | 200 | <110 | 55750 | 2860 | 13520 | 320 | <2.5 | <4.8 | 37 | <0.5 | 25 | <0.8 | 1.6 | <0.2 |

| 18 | 2 | 14.1 | 290 | 260 | <130 | 85660 | 6020 | 15040 | 280 | <3.6 | 30 | 66 | <0.7 | 9.7 | 15 | 20 | <0.5 |

Note: Fluid composition data (ppm) obtained by laser ablation ICP-MS analysis of individual fluid inclusions. Data presented represent mean values for a fluid inclusion assemblage in which several inclusions are inferred to have been co-trapped.

*N = Number of inclusions measured from each assemblage.

†Sal. = Salinity (wt% NaCl equivalent).

§Th = Homogenization temperature (°C).

#N.D. = Not determined.

< No results above the limit of detection; the value given is the minimum limit of detection recorded for an inclusion analysis in that assemblage, as the best estimate of the maximum concentration for that element.

Discussion

The observation that the highest Ag concentrations are observed in the highest salinity fluids (fluid types 1 and 2) supports the hypothesis that episodic pulses of brine were principally responsible for transport of Ag (and Zn and Pb) into the stockwork at Cerro Proaño and potentially throughout the Fresnillo hydrothermal system17. Only one value above detection was recorded for the low salinity type 3 fluids (0.5 ppm) indicating that these fluids carried one to two orders of magnitude less precious metal and were unlikely to be primary ore-forming solutions. The correlation between Ag, Zn, Pb and Cl is consistent with a predominance of Cl complexing for these metals as predicted for moderately saline, near neutral epithermal fluids19.

The observed variations in mean Ag concentration of up to an order of magnitude between different inclusion assemblages containing the same fluid type can be explained by trapping of fluids at various stages of ore mineral precipitation as has been observed for Sn, Cu, Zn and Pb in other ore deposit studies8,20,21,22. Although Ag, Zn and Pb sulfides were not observed in the samples investigated, we suggest this could be due to precipitation occurring beneath (upstream from) the sampling site, as has been previously suggested for an epithermal Pb-Zn vein system8.

The preferential transport of Ag to shallower/more distal positions to produce the broad metal zoning observed at Fresnillo23 is predicted by the higher solubility of Ag sulfides relative to base metal sulfides, e.g.24. Based on the observation of coexisting liquid- and vapor-rich inclusions, the most likely control of Ag complex destabilization in the shallower parts of the system like Cerro Proaño is boiling. This model could be tested by further laser ablation ICP-MS analyses of fluid inclusions from deeper samples.

The geochemical decoupling of Cu and, to a lesser extent, Sb from other metals and chloride concentrations has been observed in several high temperature magmatic-hydrothermal systems, both in low density vapors and dilute liquids20,25,26. This has been interpreted to reflect the predominance of an alternative complexing ligand for these metals, most likely a sulfur species for Cu27 and/or hydroxide complexing for Sb28.

Although unequivocal data are lacking, multiple lines of evidence (geochronology, isotopic data, fluid inclusion gas compositions, geological context, and regional trends in mineralization) point to a magmatic component in the fluids at Fresnillo and other Mexican silver deposits17,29, as discussed in detail by Camprubí and Albinson10. Accordingly, we compare the compositions of Fresnillo inclusion fluids to other magmatic brines to assess similarities and differences that may reflect both a characteristic magmatic source and/or evolution during migration into the epithermal environment.

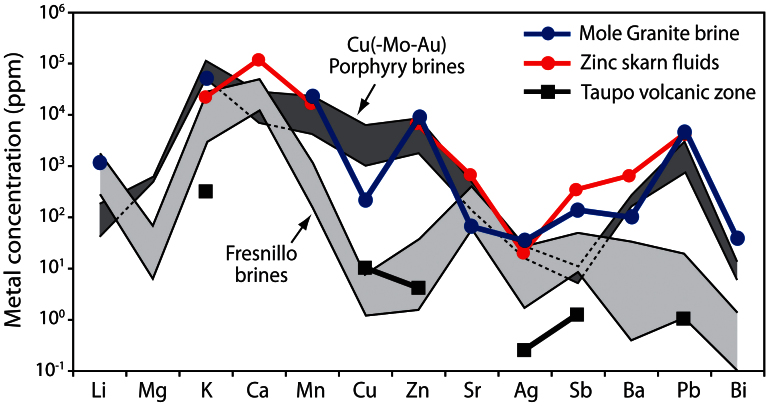

The Fresnillo brines show a number of marked differences to magmatic brines derived from both oxidized (porphyry-Cu) and reduced (Sn) felsic intrusions (Fig. 4). In particular, Cu, Zn and Pb are strongly depleted. However, the loss of these elements, together with trace metals such as Bi, can be explained by the deep level mineralization that produced Cu-Zn-Pb-rich chimney and manto deposits underlying Cerro Proaño14,17. Relatively elevated Ca and Sr can be accounted for by the replacement of calc-silicates and carbonates by sulfides during manto formation by a similar process to that recorded in the Mochito distal Zn skarn deposit, Honduras, which is also thought to have formed from evolving magmatic fluids30. The apparent depletion in Mg in the Fresnillo fluids may reflect dolomite formation in the manto-forming event14.

Figure 4. Comparison of composition of Fresnillo brines (excluding type 3 low salinity fluids) with a variety of magmatic brines from other hydrothermal ore deposits.

Oxidized porphyry copper deposit trend incorporates brine inclusion data from Bajo de la Alumbrera36, Bingham21, El Teniente37 and Butte38. Mole Granite brine inclusion data (Leno 1 sample) from Audétat et al.20. Zinc skarn fluid inclusion data (average of garnet- and pyroxene-hosted inclusions) from Williams-Jones et al.30. Taupo Volcanic Zone fluid data from Simmons and Brown5.

Other elements that show departures from typical magmatic brine ratios are Li, Ag and Sb. These are similar to, or elevated, relative to the more saline porphyry-Cu brines in the comparison, and are more akin to reduced brines derived from evolved felsic rocks, such as the Mole Granite20. A reducing character of the Ag-transporting fluid is also supported by the elevated Ba content. It is possible that such a signature reflects the relatively reduced and highly fractionated felsic intrusives that typify the Eocene-Oligocene volcanic belt of Mexico11, although a continental evaporitic brine, in particular enriched in Li, cannot be ruled out as a potential source. Nonetheless, the strong circumstantial links to active magmatism10,17,29 lead us to suggest that unusually Ag-rich brines were generated by highly evolved melts related to the Sierra Madre Occidental large igneous province, and that these could account for the remarkable silver deportment of Mexico.

Assuming that the measured fluid compositions are typical of the Fresnillo district, taking a conservative upper value for Ag solubility as 30 ppm (because some Ag sulfide precipitation is known to have already occurred beneath Cerro Proaño), and inferring a precipitation efficiency of greater than 97% (assuming that brine inclusions with Ag below a detection limit of ~1 ppm represent depleted ore fluids after silver precipitation) we calculate that approximately 1.8 km3 of brine would be required to transport the >48,000 t of silver produced in the district to date. This is a factor of around 1.5–30 times less brine than that needed to produce large magmatic-hydrothermal Cu-Mo or Sn-W deposits.

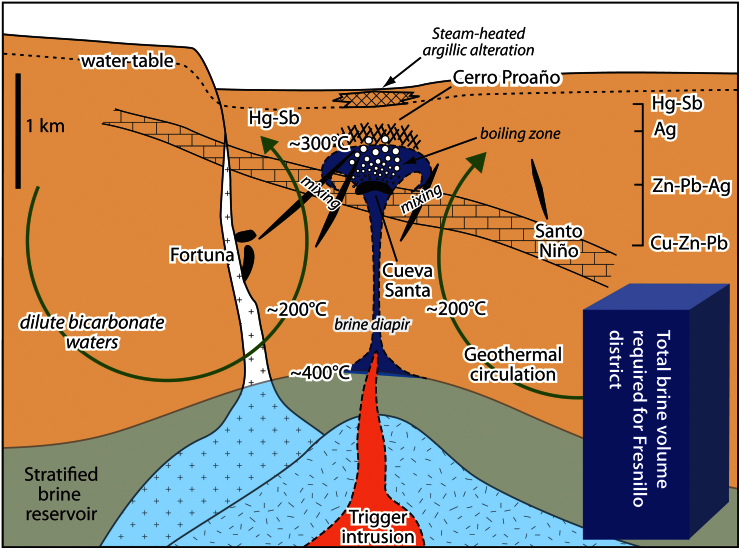

Based on our new data and previous detailed observations at Fresnillo17,31, we believe that intermittent supply of Ag-rich brines of magmatic origin best explains high ore grades, the giant metal inventory, and the paragenetic evidence for episodic mineralization12,17,31. Our suggested model for this process is shown in Figure 5. The highest Ag concentrations observed are one to two orders of magnitude greater than those reported for dilute geothermal waters in the Taupo Volcanic Zone, where a single system could flux ~50,000 tonnes of Ag in ~5,000 years assuming continuous flow and uniform metal concentrations5. The Fresnillo data, however, indicate that fluid compositions and metal concentrations can vary greatly during the lifespan of hydrothermal mineralization. Given a modest upflow rate of ~100 kg sec−1 based on modern geothermal systems and a boiling epithermal environment (<1 km depth) with depositional efficiency of >90%32, the total time required to flux 1.8 km3 of Ag-rich brine is ~500 years. If mineralization was episodic, as inferred at Fresnillo, the duration of individual pulses would have been shorter than this. However, if extreme flow rates existed during phases of epithermal vein mineralization, as recently argued by Rowland and Simmons33, then the total time required to flux the same amount of silver is <50 years, an incredibly short period considering the lifespan of a geothermal system could be up to 250,000 years.

Figure 5. Conceptual model for formation of the Fresnillo deposits by injection of brine diapirs into a geothermal circulation system, triggered by magma intrusion.

The estimated total volume of brine required to form the deposits of the Fresnillo district as a whole (~6.5 × 6.5 km) is shown approximately to scale. It is envisaged that mineralization occurred from several pulsating brine diapirs located in a number of centres, triggered by separate parent intrusions, over an extended time period. The Cerro Proaño system and its underlying veins and mantos represents one such centre.

Episodic introduction of unusually metalliferous fluids into otherwise essentially barren hydrothermal systems has been reported in other types of deposits22,34. Consequently, we suggest that this process may be a key factor in controlling the rarity and spatial and temporal episodicity of many hydrothermal ore deposits.

Methods

Polished wafer samples were studied using transmitted light microscopy and SEM-cathodoluminescence (SEM-CL) petrography in order to identify the fluid inclusion types present and their trapping chronology. SEM-CL imaging was carried out at the Natural History Museum, London, on a Jeol 5900LV scanning electron microscope fitted with Oxford INCA and Gatan cathodoluminescence detectors and operated with Oxford INCA & WAVE software. A working distance of 10 mm and beam current of ~5 nA were used at an operating pressure of 30 Pa.

Phase changes in fluid inclusions were measured using conventional microthermometry using a Linkam MDS600 heating-freezing stage mounted on a Nikon Eclipse 600 transmitted light microscope. Accuracy of temperature measurements is estimated as ±0.1°C from -100 to +30°C, and ±0.4°C at higher temperatures, based on regular calibration using an in-house synthetic H2O-CO2 fluid inclusion standard. Measurement precision is ±0.1°C for sub-ambient temperatures and ±1°C at higher temperatures. Fluid salinity was estimated from final ice melting temperatures using phase equilibria in the NaCl-H2O model system. The dominance of NaCl in the fluids is suggested by eutectic melting temperatures that are close to −22°C. Total homogenization temperatures provide a good estimate of true fluid trapping temperatures because of the evidence for fluid boiling.

Selected inclusions were analyzed using laser ablation inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) using a New-Wave Instruments 213 nm UV laser attached to a VG Instruments PQ3 quadrupole mass spectrometer (see Stoffell et al.8 for more details). Elements analyzed were Li, Na, Mg, Cl, K, Ca, Mn, Cu, Zn, Sr, Ag, Sb, Au, Ba, Pb, and Bi. External calibration was carried out via ablation of standard solutions held within pure quartz glass microcapillaries8. The reader is referred to Heinrich et al.6 for more information concerning calibration strategies and analytical uncertainty for LA-ICP-MS analysis of fluid inclusions.

Sodium concentrations are known to be overestimated due to a high background on the mass spectrometer used and its measurement on the mass spectrometer's analogue detector in the standard as opposed to the pulse counting detector for the inclusions35 and so are not reported here. For this reason, and because chloride concentrations yield better analytical accuracy (albeit with slightly lower precision)35, chloride concentration estimated from the freezing point depression measurements was used as the internal standard for reduction of the LA-ICP-MS data, e.g.8. Full results are reported in the supplementary online dataset.

Some of the fluid inclusion assemblages, in particular the more saline groups, have excess or near excess positive charge even without the inclusion of Na concentrations. The possible error associated with the determination of the major cations Ca and K is likely to be less than ~30% and ~50%, respectively35, so the most plausible explanation for this charge imbalance is the presence of another anion besides Cl−. Possible species include the sulphur-containing ligands SO42− and HS−, and also CO32− and HCO3−. Although the presence of such anions would impact on the microthermometric estimation of the internal standard values of Cl, this effect will be small because of the topology of the NaCl-Na2SO4-H2O, NaCl-NaHCO3-H2O and NaCl-Na2CO3-H2O phase diagrams. Because Ag/Cl, Zn/Cl and Pb/Cl ratios determined by LA-ICP-MS are independent of the internal standardization process and show the same relationship with salinity as the calculated concentration values, it is clear that the principal conclusion that the more saline fluids are markedly enriched in silver and base metals is robust.

Author Contributions

J.J.W., S.F.S. and B.S. designed the study and were involved in collecting and interpreting the data. S.F.S. collected the samples and provided the background geological information. J.J.W. and S.F.S. wrote and edited the main manuscript text. B.S. acquired the laser ablation ICP-MS data and the photographs shown in Figure 1. J.J.W. prepared the Figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an Albert Julius Bursary from Imperial College London to BS, with additional grants from the Society of Economic Geologists' Hugh E. McKinstry fund and the Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining. We thank Clara Wilkinson for acquisition of the SEM-cathodoluminescence images and Teresa Jeffries for assistance with LA-ICP-MS analyses.

References

- Simmons S. F., White N. C. & John D. A. Geological characteristics of epithermal precious and base metal deposits. Econ. Geol. 100th Anniv. Vol. 485–522 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Singer D. A. World-class base and precious metal deposits – a quantitative analysis. Econ. Geol. 90, 88–104 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Megaw P. K. M. Discovery of the silver-rich Juanicipio-Valdecañas zone, western Fresnillo district, Zacatecas, Mexico. Soc. Econ. Geol. Spec. Publ. 15, 119–132 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Simmons S. F. & Brown K. L. Gold in magmatic hydrothermal solutions and the rapid formation of a giant ore deposit. Science 314, 288–291 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons S. F. & Brown K. L. The flux of gold and related metals through a volcanic arc, Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand. Geology 35, 1099–1102 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich C. A. et al. Quantitative multi-element analysis of minerals, fluid and melt inclusions by laser-ablation inductively-coupled-plasma mass-spectrometry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 3473–3496 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J. J. Fluid inclusions in hydrothermal ore deposits. Lithos 55, 229–272 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Stoffell B., Wilkinson J. J. & Jeffries T. E. Metal transport and deposition in hydrothermal veins revealed by 213nm UV laser ablation microanalysis of single fluid inclusions. Am. J. Sci. 304, 533–557 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich C. A. How fast does gold trickle out of volcanoes? Science 314, 263–264 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camprubí A. & Albinson T. In Geology of México: celebrating the centenary of the Geological Society of México (eds. Alaniz-Á lvarez, S. A. & Nieto-Samaniego, Á. F.) 377–415 (Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Paper 422, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- Bryan S. E. et al. New insights into crustal contributions to large-volume rhyolite generation in the mid-Tertiary Sierra Madre Occidental Province, Mexico, revealed by U-Pb geochronology. J. Petrol. 49, 47–77 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ruvalcaba-Ruiz D. & Thompson T. B. Ore deposits of the Fresnillo mine, Zacatecas, Mexico. Econ. Geol. 83, 1583–1596 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- De Cserna Z. Geology of the Fresnillo area, Zacatecas, Mexico. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 87, 1191–1199 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald A. J., Kreczmer M. J. & Kesler S. E. Vein, manto and chimney mineralization at the Fresnillo silver-lead-zinc mine, Mexico. Can. J. Earth Sci. 23, 1603–1614 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Lang B., Steintz G., Sawkins F. J. & Simmons S. F. K/Ar age studies in the Fresnillo silver district, Zacatecas, Mexico. Econ. Geol. 83, 1642–1646 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Velador J. M., Heizler M. T. & Campbell A. R. Timing of magmatic activity and mineralization and evidence of a long-lived hydrothermal system in the Fresnillo silver district, Mexico: Constraints from 40Ar/39Ar geochronology. Econ. Geol. 105, 1335–1349 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Simmons S. F. Hydrologic implications of alteration and fluid inclusion studies in the Fresnillo District, Mexico. Evidence for a brine reservoir and a descending water table during the formation of hydrothermal Ag-Pb-Zn orebodies. Econ. Geol. 86, 1579–1601 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein R. H. & Reynolds T. J. Systematics of Fluid Inclusions in Diagenetic Minerals ( SEPM Short Course Notes, v. 31, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- Seward T. M. & Barnes H. L. In Geochemistry of hydrothermal ore deposits, 3rd Edition (ed. Barnes, H. L.) 435–486 (John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- Audétat A., Günther D. & Heinrich C. A. Causes for large-scale metal zonation around mineralized plutons: fluid inclusion LA-ICP-MS evidence from the Mole Granite, Australia. Econ. Geol. 95, 1563–1581 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Landtwing M. R. et al. Copper deposition during quartz dissolution by cooling magmatic-hydrothermal fluids: the Bingham porphyry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 235, 229–243 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Stoffell B., Appold M. S., Wilkinson J. J., Mclean N. A. & Jeffries T. E. Geochemistry and evolution of MVT mineralising brines from the Tri-State and Northern Arkansas districts determined by LA-ICP-MS microanalysis of fluid inclusions. Econ. Geol. 103, 1411–1435 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Stone J. B. & McCarthy J. C. Mineral and metal variations in the veins of Fresnillo, Zacatecas, Mexico. Am. Inst. Min. Eng. Trans. 148, 91–106 (1948). [Google Scholar]

- Wood S. A. & Samson I. M. Solubility of ore minerals and complexation of ore metals in hydrothermal solutions. Rev. Econ. Geol. 10, 33–77 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich C. A., Gunther D., Audétat A., Ulrich T. & Frischknecht R. Metal fractionation between magmatic brine and vapor, determined by microanalysis of fluid inclusions. Geology 27, 755–758 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J. J. et al. In Proc. PACRIM 2008 congress, Gold Coast, Australia 295–298 (Austral. Inst. Min. Metall., Carlton, Victoria, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Seo J. H., Guillong M. & Heinrich C. A. The role of sulfur in the formation of magmatic-hydrothermal copper-gold deposits. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 282, 323–328 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Pokrovski G. S. et al. Antimony speciation in saline hydrothermal fluids: a combined X-ray absorption fine structure and solubility study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 4196–4214 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Albinson T., Norman D. I., Cole D. & Chomiak B. A. Controls on formation of low-sulfidation epithermal deposits in Mexico: constraints from fluid inclusion and stable isotope data. Soc. Econ. Geol. Spec. Publ. 8, 1–32 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Jones A. E., Samson I. M., Ault K. M., Gagnon J. E. & Fryer B. J. The genesis of distal zinc skarns: Evidence from the Mochito Deposit, Honduras. Econ. Geol. 105, 1411–1440 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Gemmell J. B., Simmons S. F. & Zantop H. The Santo Niño silver-lead-zinc vein, Fresnillo District, Zacatecas, Mexico: Part I. Structure, vein stratigraphy, and mineralogy. Econ. Geol. 83, 1597–1618 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Brown K. L. Gold deposition from geothermal discharges in New Zealand. Econ. Geol. 81, 979–983 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Rowland J. & Simmons S. F. Hydrologic, magmatic, and tectonic controls on hydrothermal flow, Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand: implications for the formation of epithermal vein deposits. Econ. Geol. 107, 427–457 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J. J., Stoffell B., Wilkinson C. C., Jeffries T. E. & Appold M. S. Anomalously metal-rich fluids form hydrothermal ore deposits. Science 323, 764–767 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckroyd C. C. Development of the 213nm UV laser ablation ICP-MS technique for fluid inclusion microanalysis and application to contrasting magmatic-hydrothermal systems. Unpub. PhD Thesis, Imperial College, University of London, 480 p. (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich T., Günther D. & Heinrich C. A. The evolution of a porphyry Cu-Au deposit, based on LA-ICP-MS analysis of fluid inclusions: Bajo de la Alumbrera, Argentina. Econ. Geol. 96, 1743–1774 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Klemm L. M., Pettke T., Heinrich C. A. & Campos E. Hydrothermal evolution of the El Teniente deposit, Chile: porphyry Cu-Mo ore deposition from low-salinity magmatic fluids. Econ. Geol. 102, 1021–1045 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Rusk B., Reed M., Dilles J. H., Klemm L. & Heinrich C. A. Compositions of magmatic hydrothermal fluids determined by LA-ICP-MS of fluid inclusions from the porphyry copper-molybdenum deposit at Butte, Montana. Chem. Geol. 210, 173–199 (2004). [Google Scholar]