Abstract

Amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) toxicity and tau hyperphosphorylation are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). How their molecular relationships may affect the etiology, progression, and severity of the disease, however, has not been elucidated. We now report that incubation of foetal rat cortical neurons with Aβ up-regulates expression of the Regulator of Calcineurin gene RCAN1, and this is mediated by Aβ-induced oxidative stress. Calcineurin (PPP3CA) is a serine-threonine phosphatase that dephosphorylates tau. RCAN1 proteins inhibit this phosphatase activity of calcineurin. Increased expression of RCAN1 also causes up-regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK3β), a tau kinase. Thus, increased RCAN1 expression might be expected to decrease phospho-tau dephosphorylation (via calcineurin inhibition) and increase tau phosphorylation (via increased GSK3β activity). We find that, indeed, incubation of primary cortical neurons with Aβ results in increased phosphorylation of tau, unless RCAN1 gene expression is silenced, or antioxidants are added. Thus we propose a mechanism to link Aβ toxicity and tau hyperphosphorylation in AD: In our hypothesis, Aβ causes mitochondrial oxidative stress and increases production of reactive oxygen species, which result in an up-regulation of RCAN1 gene expression. RCAN1 proteins then both inhibit calcineurin and induce expression of GSK3β. Both mechanisms shift tau to a hyperphosphorylated state. We also find that lymphocytes from persons whose ApoE genotype is ε4/ε4 (with high risk of developing AD) show higher levels of RCAN1 and phospho-tau than those carrying the ApoE ε3/ε3 or ε3/ε4 genotypes. Thus up-regulation of RCAN1 may be a valuable bio-marker for Alzheimer’s disease risk.

Keywords: oxidative stress, beta-amyloid toxicity, Alzheimer’s disease, RCAN1

Introduction

Amyloid-β (Aβ) toxicity and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, are major hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but the molecular interactions between them are not well understood. This lack of knowledge is especially important to overcome in view of a recent report showing that there are synergistic interactions between Aβ and tau to accelerate neuropathology and cognitive decline in AD [1].

The Regulator of Calcineurin 1 gene, RCAN1[2], formerly known as Adapt78 or DSCR1, is strongly expressed in many brain regions [3]. The differential expression of various members of the RCAN1 family of proteins that are generated by alternative splicing of the gene’s seven exons (e.g. RCAN1–4, RCAN1-1L, and RCAN1-1S) suggests selective functions in normal brain physiology and in neurodegenerative diseases [4, 5]. RCAN1–4 is transiently up-regulated in acute oxidative stress, and has been shown to potentiate adaptive responses in such short-term oxidative stress models [6]. In contrast, chronic overexpression of RCAN1 proteins could be expected to result in chronic calcineurin inhibition, which should cause higher steady-state levels of phosphorylation of calcineurin targets. One such target in neurons is the tau protein [7]. Previously, one of our laboratories (JV) reported that Aβ causes mitochondrial oxidative stress [8] and the other(KJD) that chronic RCAN1 overexpression, and chronically elevated levels of RCAN1-1 protein is associated with AD [9, 10, 5] and, of course, hyperphosphorylated tau is one of the hallmarks of AD [1].

The Aβ42 peptide stimulates transcription of RCAN1, in the immortalized human glioblastoma/astrocytoma U-373 MG cell line [9]. Incubation of cultured neurons, or even mitochondria, with Aβ leads to increased formation of reactive oxygen species; this is likely the source of the chronic oxidative stress associated with AD [8, 11, 12]. Additionally, overexpression of a RCAN1 transgene, with a tet-off inducible promoter, stimulates transcription and translation of the glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK3β) in PC-12 cells [13], and GSK-3β is one of the kinases responsible for phosphorylating the tau protein. Thus, the possibility exists that in AD, Aβ may induce RCAN1 overexpression through chronic oxidative stress, leading, via calcineurin inhibition and GSK3β synthesis, to hyperphosphorylation of tau. This enticing hypothesis, which might explain at least part of AD etiology [5, 9, 10], remains to be properly tested.

In the current work, we have explored the hypothesis in two important new ways: Firstly, we have performed the first studies of RCAN1 and GSK3β synthesis, as well as consequent tau phosphorylation, in primary cortical neurons exposed to Aβ. We also tested whether antioxidants or RCAN1 silencing could prevent tau hyperphosphorylation. Secondly, we have tested whether individuals carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 allele (a known risk for AD) express RCAN1 at higher levels in lymphocytes than do those carrying the ApoE ε3/ε4 or ApoE ε3/ε3 alleles; such measurements could even provide a useful peripheral bio-marker for AD risk.

Materials & Methods

Subjects

Volunteers were from the Department of Neurology, Hospital Clínico Universitario of Valencia (Spain). We recruited 36 women (aged 35–45) who were clinically normal but whose parents (who carried the ApoE (ε4/ε4) genotype had been diagnosed with AD (NINDCS-ADRA workgroup criteria [14]. We genotyped all the 36 women for ApoE, and randomly selected twelve of those who carried the apoE, ε3/ε4 and twelve carrying the apoE, ε4/ε4 genotypes. Then we recruited 21 age-matched, apparently normal persons (no family history of AD) genotyped them, and randomly selected twelve of those who carried the apoE, ε3/ε3 allele. At the time of enrolment, persons involved were not taking any other antioxidant or psychoactive medication. This study was approved by the Committee on Ethics in Medical Research of the Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valencia, Spain.

Animals

Young female (5- to 6-month-old) Wistar rats were used. Animals were housed in a clean environment at constant temperature and humidity and with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. They were fed on a standard laboratory diet (containing 590 g carbohydrates, 30 g lipids, and 160 g protein per kilogram of diet) and tap water ad libitum. In all cases, animals were treated in accordance with the accepted norms for the good care of laboratory animals. This study was approved by the Committee of Ethics in Animal Research, University of Valencia.

PC12 cell line

PC12 cells were obtained as a kind gift of Dr Catarina Oliveira (Coimbra, Portugal). They were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum in 5% CO2 in air at 37°C in 25 or 75 cm2 flasks. Cells were cultured in plaques previously treated with poly-L-Lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). For all of the differentiation assays, PC12 cells were treated with 50 ng/ml NGF (Nerve Growth Factor, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in defined media (RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 0.25% foetal calf serum) for six days; The NGF and medium were replaced every two days. All of the media, serum and supplements used throughout this study were obtained from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA).

Primary cortical neuronal cell cultures

Wistar rats were sacrificed at day 14 of gestation, and foetal cortical neurons were isolated. The cells were dissociated mechanically and were filtered through a nylon mesh (pore size of 90 μm). Cell suspensions were seeded in plates previously treated with poly-L-Lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at a density of 51×104cells/mm2. Cells were cultured for 1h and then they were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco Invitrogen Corporation, Barcelona, Spain), containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cultures were grown in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. To prevent non-neuronal proliferation, 5μM cytosine-β-D-arabinofuranoside was added on the 4th day of culture and, after 24 hours, half of the culture medium was replaced by fresh DMEM. The level of glial contamination was less than 3%.

Isolation of lymphocytes

We used BD Vacutainer CPT tubes to separate plasma, white cells and erythrocytes. After centrifugation, we removed the white ring containing mononuclear cells. Mononuclear cells were washed twice in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) and finally in foetal bovine serum to eliminate platelets. After incubation of cells on Petri plates with RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 10% foetal bovine serum for 24 hours, lymphocytes remained in the supernatant while the rest of the cells, adhered to the plates.

Incubation with Aβ peptide

We used 10 μM soluble Aβ 1–42 or 42-1 peptides (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), as previously described in [8]. Briefly, soluble Aβ 1-42 or 42-1 peptides were dissolved as follows: 100 nmol of peptide were dissolved in 200 μl of 1% NH4OH and 800 μl of sterile PBS (Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation, Barcelona, Spain), and incubated for 24 hours at 4°C. In all controls we added the inactive 42-1 peptide. The concentration of Aβ peptide used was similar to that present in brain of AD patients [15].

Antioxidant treatments

We used GSH-mono ethyl ester or Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid), a water-soluble derivative of vitamin E, as antioxidants. Both were from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. We prepared a 100 mM stock solution of either of these in sterile PBS and we used them at a final concentration of 1 mM.

Silencing RCAN1 mRNA

Silencing experiments are very difficult to perform in neurons and this we turned to PC12 cells which under the right experimental. The SiRNA was obtained from Dharmacon Inc. (Lafayette CO, USA). We used the “Ontarget plus- Smart Pool” protocol and followed the Dharmacon’s instructions.

Measurement of glutathione

Reduced and oxidized glutathione (GSH and GSSG) was measured by HPLC, as previously described [16].

Western blotting analysis

Proteins were detected by Western blotting using the Protoblot Western Blot AP System (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA) and a specific antibody for the protein studied. For tau hyperphosphorylation we used phospho-tau (Thr231) antibody (ABR- Affininty Bioreagents Inc., CO), a specific target of GSK3β activity. And for studying the expression of GSK3β we used and anti- GSK3β polyclonal antibody (MBL, Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Tokio, Japan).

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed by the least-significant difference test, which consists of two steps: first an analysis of variance was performed. The null hypothesis was accepted for all numbers of those sets in which F was non-significant, at the level of p < 0.05. Second, the sets of data in which F was significant were examined by the modified t-test using p ≤ 0.05 as the critical limit.

Results

Aβ peptide increases RCAN1 and GSK3β expression, and increases tau phosphorylation

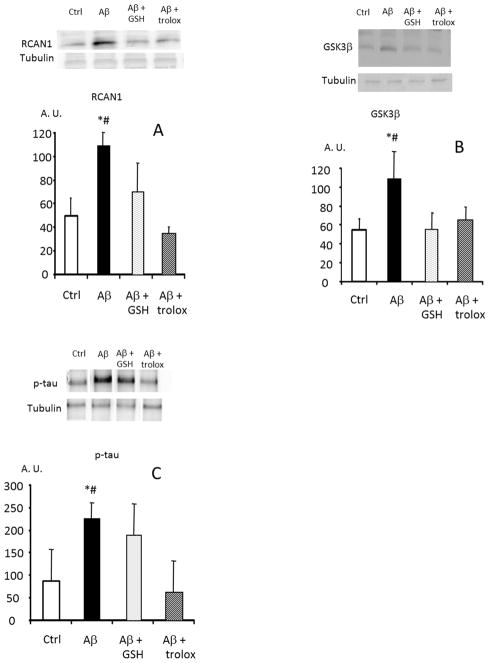

Exposure of primary cortical neurons in culture to Aβ caused significant, two-to-three fold increases in RCAN1 and GSK3β protein levels, and a concomitant increase in tau phosphorylation (Fig. 1A, 1B, 1C).

FIGURE 1. Amyloid β peptide causes an increased expression of RCAN1, GSK3β and a tau hyperphosphorylation in rat cortical neurons in primary culture. Prevention by antioxidants.

Isolated neurons were cultured with 10 μM amyloid β 42-1 (controls), 10 μM amyloid β 1-42 peptide and 1mM GSH-ester or 1 mM trolox where indicated. In panel A levels of RCAN 1 were measured. In panel B, GSK3 β and in panel C, P-tau (tau phosphorylated in threo 231) was determined. Representative western blots are shown. In all cases, values are means ± SD of 6 experiments are shown. * p<0.05 compared to controls; # p<0.05 compared to cells incubated with antioxidants.

Aβ toxicity, RCAN1 and GSK3β expression, and tau phosphorylation all involve oxidative stress

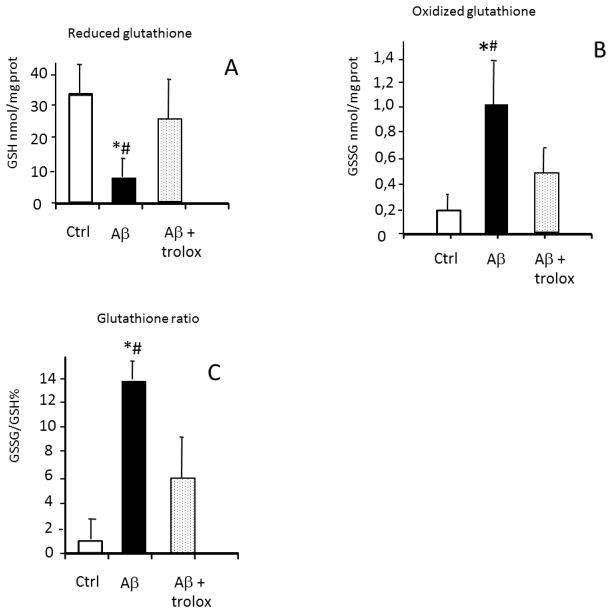

One of our labs. has previously reported that incubation of primary neurons in culture with Aβ causes an increase in the level of peroxides from 0.45 nmol/million viable cells to 1.4 nmol/million viable cells [17]. Now we tested whether glutathione is oxidized in the presence of Aβ. Incubation with the toxic amyloid peptide caused a very significant decrease in reduced glutathione (Fig. 2A). Consequently, oxidized glutathione was increased from 0.2±0.1 to 1.0±0.4 nmol/mg of protein (Fig. 2B), and the glutathione redox ratio GSSG/GSH (expressed as a percentage) was very significantly increased from a value of 0.6% to a value of 14% (Fig. 2C). These data provide primary evidence that the Aβ peptide causes a significant oxidative stress in primary cortical neurons in culture.

FIGURE 2. Incubation of neurons with amyloid β 1-42 causes oxidative stress evidenced by an oxidation of glutathione. Prevention by antioxidants.

Isolated neurons were cultured with 10 μM amyloid β 42-1 (controls), 10 μM amyloid β 1-42 peptide and 1 mM trolox where indicated. We measured in panel A, GSH levels (panel A), GSSG levels (panel B) and we calculated the GSSG/ GSH (panel C). * p<0.05 compared to controls; # p<0.05 compared to cells incubated with antioxidants.

Without Aβ exposure, the antioxidants glutathione ester or trolox (the water soluble analogue of vitamin E), had no effect on RCAN1, GSK3β, or tau phosphorylation in cultured primary neurons. Glutathione and trolox, however, effectively prevented the Aβ-induced increases in RCAN1 and GSK3β expression, as well as the increased tau phosphorylation in our primary neurons (Fig. 1A, 1B, 1C). Thus, it is likely that the oxidative stress induced by Aβ was responsible for increased RCAN1 and GSK3β expression, and for increased tau phosphorylation.

RCAN1 gene silencing prevents tau hyperphosphorylation caused by Aβ peptide

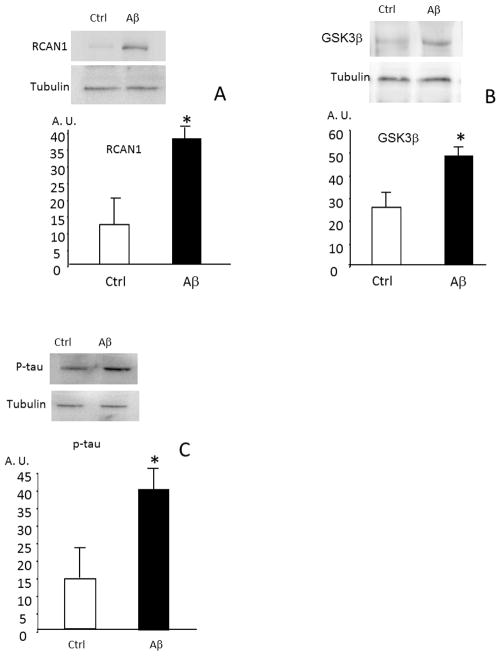

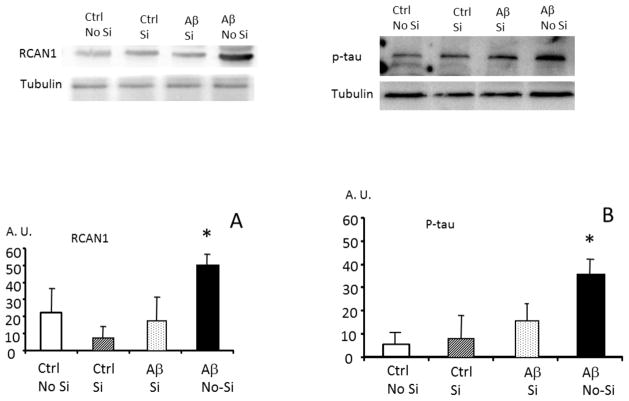

The experiments reported above, showing that Aβ causes an increased expression ofRCAN1, an increased expression of GSK3β and an increased tau hyper-phosphorylation required a critical test: the silencing of RCAN1 in cells to test whether preventing RCAN1 expression would also prevent Aβ from increasing phosphorylation of tau. We performed silencing experiments in PC12 cells which, under appropriate conditions, will differentiate into neuron-like cells. We found that RCAN1 expression, GSK3β expression and tau hyper-phosphorylation (Fig. 3A, 3B, 3C) are all significantly increased in PC12 cells incubated with Aβ, thus confirming the results we obtained with primary neurons in culture in Figs 1A, 1B, and 1C. Next, we tested whether RCAN1 gene expression could be silenced in PC12 cells, and whether RCAN1 silencing would prevent the hyperphosphorylation of tau caused by incubation with Aβ. In Fig. 4 we show that the increase in RCAN1 protein levels induced by Aβ was, indeed, blocked by RCAN1 siRNA. In Panel B we show that tau was hyperphosphorylated in the presence of Aβ, but that this was blocked by RCAN1 gene silencing.

FIGURE 3. Amyloid β peptide causes an increased expression of RCAN1, GSK3 β and a tau hyperphosphorylation in PC12 cells in culture.

Isolated neurons were cultured with 10 μM amyloid β 1-42 peptide where indicated. In panel A levels of RCAN 1 were measured. In panel B, GSK3 β and in panel C, P-tau (tau phosphorylated in threo 231). Representative western blots are shown. In all cases, values are means ± SD of 6 experiments. * p<0.05 compared to controls (incubated with 4 peptide (42-1).

FIGURE 4. Silencing RCAN1 prevents Amyloid β peptide-induced tau hyperphosphorylation in PC12 cells in culture.

PC 12 cells were cultured in the presence of 10 μM amyloid β1-42 and 42-1 peptides. The level of RCAN 1 (panel A) and of P-tau (tau phosphorylated in threo 231, panel B) were determined. Si indicates that the cells were silenced for RCAN 1. As expected amyloid β cause an increase in RCAN 1 (panel A) and in P- tau (panel B) but this did not occur when RCAN 1 was silenced (panel B). Representative western blots are shown. In all cases, values are means ± SD of 3 experiments. *p<0.05 compared to RCAN1 silenced neurons incubated with Aβ.

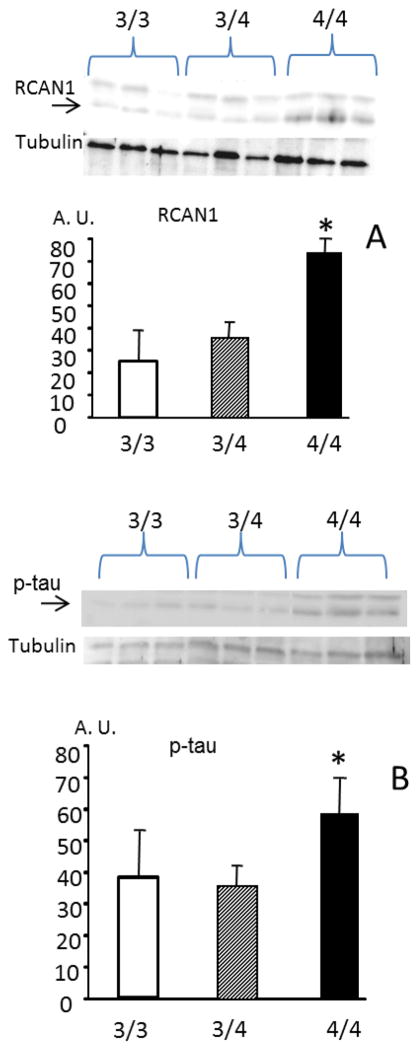

Expression of RCAN, and Phospho- tau is higher in persons carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotype than in those carrying ApoE ε3/ε3, or even ApoE ε3/ε4

The search for early markers of AD is a major undertaking. Lymphocytes have been shown to be suitable surrogates to study AD pathology when, for obvious ethical reasons, this cannot be done in neurons [18]. We aimed at studying pre-symptomatic persons who may be at high risk for developing AD, i.e., those carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotype. Figure 5A shows that RCAN1 protein levels are almost three-fold higher in lymphocytes from persons carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotype than in those carrying ApoE ε3/ε3 or ApoE ε3/ε4. In agreement with our prediction, phospho-tau was also significantly increased in persons carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotype, compared with those carrying either the ApoE ε3/ε4 or ε3/ε3 genotypes (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5. RCAN 1 and Phospho tau levels in lymphocytes from normal persons carrying the ApoE ε3/ε3, ApoEε3/ε4 and ApoE ε4/ε4 genotpyes.

(A) RCAN1 and (B) Phospho-tau are over-expressed in lymphocytes from persons carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotype before the onset of any clinical symptoms of the disease. In panel A, the arrow indicates the RCAN1 band and in panel B, it indicates P-tau Persons at high risk of Alzheimer’s (4/4) express more RCAN1 and have more P- tau * p < 0.05 of 4/4 than those at low risk (3/4 or 3/3 genotypes)

Discussion

The most significant new findings reported in this paper are that RCAN1 protein levels, GSK3β protein levels, and tau phosphorylation are all increased when primary cortical neurons, are incubated with the Aβ peptide, and that these effects are all abrogated by inclusion of the antioxidants glutathione or trolox (Figure 1A, 1B, 1C). RCAN1 is a gene that responds to oxidative stress [6]. The importance of oxidative stress in AD was first reported by the group of George Perry [12,19,20]. Both Cardoso et al. (2001) [21], and Butterfield et al. (2006) [22] observed that mitochondria were essential for the development of oxidative stress associated with Aβ toxicity. The association of calcineurin and RCAN1 with both Alzheimer disease pathology and oxidative stress has been reported [6, 9, 23, 5, 10]. Thus, the possibility that RCAN1 (which inhibits calcineurin) might be involved in the development of AD pathology has been known for quite some time. The linking of Aβ peptide with tau hyperphosphorylation via RCAN1 was proposed by one of our labs. as an hypothesis [5, 9, 10, 13, 23] but to our knowledge it has not been tested experimentally.

RCAN1 overexpression has been demonstrated in post-mortem brain studies of Alzheimer patients [9] and Down syndrome patients [6,9,24], who suffer an early-onset and aggressive form of Alzheimer disease. RCAN1 overexpression could be expected to cause calcineurin inhibition and, therefore, decreased tau dephosphorylation. The finding that RCAN1 itself causes GSK3β expression, with concomitant increases in tau phosphorylation, suggests that tau is being ‘attacked’ from both sides when cells are exposed to Aβ. Induction of GSK3β by RCAN1, however, had previously only been tested in a very artificial system, via overexpression of an RCAN1 transgene, with a tet-off inducible promoter, in PC12 cells [13]. The present results now expand previous observations, and show that Aβ alone is sufficient to cause GSK3β synthesis in cortical primary neurons: presumably via RCAN1 induction. The involvement of oxidative stress in this process seems clear, since GSK3β synthesis was prevented when either a GSH-ester or trolox were added to cells exposed to the Aβ peptide (Fig. 1B). A recent report by Terwel et al. (2008) [25], showing that Aβ activates GSK3β and aggravates tauopathy in mice, would seem to validate the significance of our findings.

Ever since Alzheimer’s first description of the disease [26] it has been clear that patients exhibit extraneuronal deposition of amyloid plaques and intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles which are mainly composed of tau protein in a hyperphosphorylated state. The contribution of each of these pathological lesions to the development of the disease was, and to a large extent still is, not well understood. Moreover, these two lesions, Aβ deposits and tau hyperphosphorylation, have not been related in a clear-cut molecular way. The central and mechanistic involvement of RCAN1 in this process is the main idea that we report in this paper.

Lymphocytes have been shown to be appropriate cells to study AD pathology when, for obvious ethical reasons, this cannot be accomplished in neurons [18]. Our results (Fig. 5A) show that RCAN1 protein levels are significantly higher in lymphocytes of persons carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotype than in those carrying ApoE ε3/ε3 or ApoE ε3/ε4. In agreement with our prediction, RCAN1, and phospho-tau were both increased in persons carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotype, but not in those carrying the ApoE ε3/ε4 or ε3/ε3 genotypes (Fig. 5B).

ApoE (ε4/ ε4) genotype has been associated with an increased oxidative stress. Mild cognitive impairment is also associated with more free radical activity To explain this the possibility of the ε4 allele was postulated as a factor of risk to suffer oxidative stress. Clearly more studies are required to explain the high risk of Alzheimer’s in persons carrying the ApoE ε4/ε4 phenotype.

In this context, two very interesting papers have appeared in which the concept of pre-clinical AD is coined. Individuals with normal ante-mortem psychometric scores that meet the post-mortem neuropathological criteria for AD can be termed pre-clinical AD patients [27]. In these patients there are elevated levels of 4-hydroxynonenal, reflective of increased oxidative stress, in the brain [28]. With this framework in mind, we would like to propose that up-regulating of RCAN1 may be an early peripheral biomarker of pre-clinical AD. We base this assertion on the fact that normal subjects who carry the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotype already show signs of increased RCAN1 together with an increase in hyperphosphorylated tau before the onset of clinical symptoms.

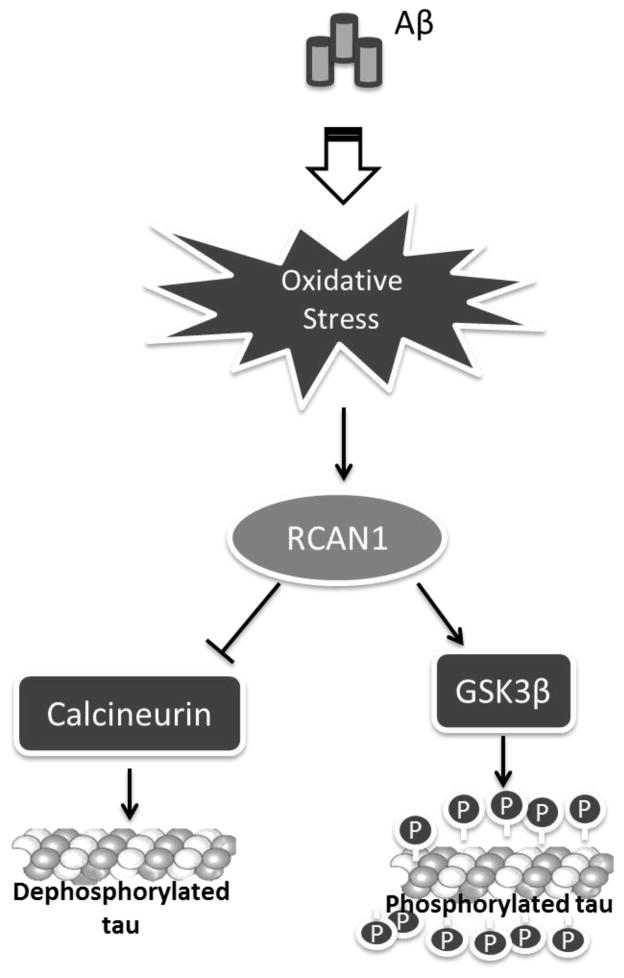

Synergies between Aβ and tau and α-synuclein [1] have been recently described. These authors suggest that Aβ and tau work together to cause neuronal damage that is typical of AD. In this paper, consistent with that hypothesis, we suggest that the hyper-phosphorylation of tau is a consequence of Aβ toxicity via RCAN1 and GSK3β. Ballatore et al. (2007) [29] reviewed evidence that there is a dynamic equilibrium of tau microtubule binding which occurs when the balance of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation shifts towards phosphorylation. Experiments reported here support that view, provide a sequential mechanism for Aβ and tau toxicities, and suggest possible means of preventing the onset of AD by interfering with the pathway outlined in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic representation of the proposed pathway linking Alzheimer’s amyloid β toxicity and tau phosphorylation involving oxidative stress and RCAN1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants to JV: Foundation Gent per Gent and SAF2010-19498 from the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (MEC) co-financed with European FEDER funds; ISCIII2006-RED13-027 from the “Red Temática de investigación cooperativa en envejecimiento y fragilidad (RETICEF), and EU Funded COSTB35 and Prometeo 2010/074 from the Generalitat Valenciana. EG was the beneficiary of a Juan de la Cierva grant 2010-MICINN.

This work was also supported by grant # RO1-AG016256 from the NIH/NIA to KJAD, and by grant #RO1-ES003598, and by ARRA Supplement 3RO1-ES 003598-22S2, both from the NIH/NIEHS to KJAD.

RCAN1 antibodies were a kind gift of Dr Mariona Arbones, Center for genomic regulation, Barcelona (Spain)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Clinton LK, Blurton-Jones M, Myczek K, Trojanowski JQ, LaFerla FM. Synergistic Interactions between Abeta, tau, and alpha-synuclein: acceleration of neuropathology and cognitive decline. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7281–7289. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0490-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies KJA, Ermak G, Rothermel BA, Pritchard M, Heitman J, Ahnn J, Henrique-Silva F, Crawford D, Canaider S, Strippoli P, Carinci P, Min KT, Fox DS, Cunningham KW, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Zhang Z, Williams RS, Gerber HP, Pérez-Riba M, Seo H, Cao X, Klee CB, Redondo JM, Maltais LJ, Bruford EA, Povey S, Molkentin JD, McKeon FD, Duh EJ, Crabtree GR, Cyert MS, de la Luna S, Estivill X. Renaming the DSCR1/Adapt78 gene family as RCAN: regulators of calcineurin. FASEB J. 2007;21:3023–3028. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7246com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell AN, Jayakumar L, Koleilat I, Qian J, Sheehan C, Bhoiwala D, Hushmendy SF, Heuring JM, Crawford DR. Brain expression of the calcineurin inhibitor RCAN1 (Adapt78) Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;467:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris CD, Ermak G, Davies KJA. Multiple roles of the DSCR1 (Adapt78 or RCAN1) gene and its protein product calcipressin 1 (or RCAN1) in disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2477–2486. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5085-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ermak G, Davies KJA. DSCR1(Adapt78)--a Janus gene providing stress protection but causing Alzheimer’s disease? IUBMB Life. 2003;55:29–31. doi: 10.1080/1521654031000066820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford DR, Leahy KP, Abramova N, Lan L, Wang Y, Davies KJA. Hamster adapt78 mRNA is a Down syndrome critical region homologue that is inducible by oxidative stress. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;342:6–12. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norman SG, Johnson GV. Compromised mitochondrial function results in dephosphorylation of tau through a calcium-dependent process in rat brain cerebral cortical slices. Neurochem Res. 1994;19:1151–1158. doi: 10.1007/BF00965149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloret A, Badía MC, Mora NJ, Ortega A, Pallardó FV, Alonso MD, Viña J. Gender and age-dependent differences in the mitochondrial apoptogenic pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:2019–2025. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ermak G, Morgan TE, Davies KJA. Chronic overexpression of the calcineurin inhibitory gene DSCR1 (Adapt78) is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38787–38794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris CD, Ermak G, Davies KJA. RCAN1-1L is overexpressed in neurons of Alzheimer’s disease patients. FEBS J. 2007;274:1715–1724. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morais Cardoso S, Swerdlow RH, Oliveira CR. Induction of cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis by amyloid beta 25–35 requires functional mitochondria. Brain Res. 2002;93:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MA, Perry G, Richey PL, Sayre LM, Anderson VE, Beal MF, Kowall N. Oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s. Nature. 1996;382:120–121. doi: 10.1038/382120b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ermak G, Harris CD, Battocchio D, Davies KJA. RCAN1 (DSCR1 or Adapt78) stimulates expression of GSK-3beta. FEBS J. 2006;273:2100–2109. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, Beach T, Kurth JH, Rydel RE, Rogers J. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asensi M, Sastre J, Pallardo FV, Estrela JM, Vina J. Determination of oxidized glutathione in blood: high-performance liquid chromatography. Methods Enzymol. 1994;234:367–371. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)34106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallés SL, Borrás C, Gambini J, Furriol J, Ortega A, Sastre J, Pallardó FV, Viña J. Oestradiol or genistein rescues neurons from amyloid beta-induced cell death by inhibiting activation of p38. Aging Cell. 2008;7:112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armentero MT, Sinforiani E, Ghezzi C, Bazzini E, Levandis G, Ambrosi G, Zangaglia R, Pacchetti C, Cereda C, Cova E, Basso E, Celi D, Martignoni E, Nappi G, Blandini F. Peripheral expression of key regulatory kinases in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MA, Richey PL, Taneda S, Kutty RK, Sayre LM, Monnier VM, Perry G. Advanced Maillard reaction end products, free radicals, and protein oxidation in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;738:447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb21836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Praprotnik D, Smith MA, Richey PL, Vinters HV, Perry G. Plasma membrane fragility in dystrophic neurites in senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease: an index of oxidative stress. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;91:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s004010050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cardoso SM, Santos S, Swerdlow RH, Oliveira CR. Functional mitochondria are required for amyloid beta-mediated neurotoxicity. FASEB J. 2001;15:1439–1441. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0561fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butterfield DA, Perluigi M, Sultana R. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease brain: new insights from redox proteomics. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;545:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ermak G, Harris CD, Davies KJA. The DSCR1 (Adapt78) isoform 1 protein calcipressin 1 inhibits calcineurin and protects against acute calcium-mediated stress damage, including transient oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2002;16:814–824. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0846com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuentes JJ, Genesca L, Kingsbury TJ, Cunningham KW, Perez-Riba M, Estivill X, de la Luna S. DSCR1, overexpressed in Down syndrome, is an inhibitor of calcineurin-mediated signaling pathways. Human Mol Genet. 2000;9:1681–1690. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.11.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwel D, Muyllaert D, Dewachter I, Borghgraef P, Croes S, Devijver H, Van Leuven F. Amyloid activates GSK-3beta to aggravate neuronal tauopathy in bigenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:786–798. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alzheimer A. Uber eine eigenartige Erkrankung der Hirnrinde. Allg Zeitschr Psychiatr. 1907;4:146–148. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aluise CD, Robinson RA, Beckett TL, Murphy MP, Cai J, Pierce WM, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Preclinical Alzheimer disease: brain oxidative stress, Abeta peptide and proteomics. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;39:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradley MA, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Increased levels of 4-hydroxynonenal and acrolein in the brain in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1570–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ballatore C, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrn2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]