Abstract

Notch signaling is required for vascular development and tumor angiogenesis. Although inhibition of the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 can restrict tumor growth and disrupt neo-vasculature, the effect of inhibiting Notch receptor function on angiogenesis has yet to be defined. In this study, we generated a soluble form of the Notch1 receptor (Notch1 decoy) and assessed its effect on angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Notch1 decoy expression reduced signaling stimulated by the binding of three distinct Notch ligands to Notch1 and inhibited morphogenesis of endothelial cells overexpressing Notch4. Thus, Notch1 decoy functioned as an antagonist of ligand-dependent Notch signaling. In mice, Notch1 decoy also inhibited vascular endothelial growth factor–induced angiogenesis in skin, establishing a role for Notch receptor function in this process. We tested the effects of Notch1 decoy on tumor angiogenesis using two models: mouse mammary Mm5MT cells overexpressing fibroblast growth factor 4 (Mm5MT-FGF4) and NGP human neuroblastoma cells. Exogenously expressed FGF4 induced Notch ligand expression in Mm5MT cells and xenografts. Notch1 decoy expression did not affect tumorigenicity of Mm5MT-FGF4 cells in vitro but restricted Mm5MT-FGF4 xenograft growth in mice while markedly impairing neoangiogenesis. Similarly, Notch1 decoy expression did not affect NGP cells in vitro but disrupted vessels and decreased tumor viability in vivo. These results strongly suggest that Notch receptor signaling is required for tumor neoangiogenesis and provides a new target for tumor therapy.

Introduction

Angiogenesis is exquisitely regulated by multiple signal pathways, including vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF), fibroblast growth factors (FGF), and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). Among these, VEGF critically influences almost all steps of angiogenesis, including endothelial proliferation, survival, and tube formation (1). Consistent with this protean role, VEGF inhibitors reduce angiogenesis in preclinical models and have been clinically validated as cancer therapy (2). Despite this established efficacy, different tumor types exhibit widely varying susceptibility to VEGF blockade (2). The underlying reasons for this variability are not clear. One possibility is that alternative signals rescue tumor vasculature, allowing for perfusion despite VEGF inhibition. Identification of such pathways is therefore of clear therapeutic importance.

The highly conserved Notch gene family encodes transmembrane receptors (Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, Notch4) and ligands [Jagged1, Jagged2, Delta-like 1 (Dll1), Dll3, Dll4], also transmembrane proteins. Upon ligand binding, the Notch cytoplasmic domain (NotchIC) is released by presenilin/γ-secretase (3). Notch signaling defects produce severe vascular defects in embryos (4), with haploinsufficiency of Dll4 causing lethality. The potential role of Notch signaling in tumor angiogenesis has thus excited much recent interest. Mice transgenic for a Dll4 reporter construct show expression in tumor endothelial cells (EC; ref. 5) and increased Dll4 expression has been detected in human cancers (6, 7). Two recent reports confirm that Dll4 plays a critical role in neoplastic endothelium, as Dll4 blockade suppresses growth and perfusion in experimental tumors (8, 9). Intriguingly, in these studies Dll4 inhibition disorganized tumor vasculature rather than simply preventing vessel proliferation, suggesting that Dll4 is required for the assembly of functional vessels.

Recent data indicate that Notch receptors also play a role in tumor angiogenesis. For example, in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), HGF was shown to up-regulate expression of Jagged1 on tumor cells, but not on endothelium. Increased Jagged1 expression activated Notch signaling in neighboring ECs, stimulating tumor angiogenesis and growth in mice (10). Thus, these data suggest that there are at least two distinct mechanisms for activating Notch signaling in tumor endothelium.

Accumulating evidence shows the intricate linkage of Notch activation and VEGF signaling. VEGF can induce the expression of Notch receptors and Dll4 (11), with Dll4 reducing expression of VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) in ECs, contributing to feedback regulation of VEGF (12). More recently, Notch receptors have been shown to regulate the expression of endothelial VEGFRs (13). These studies suggest that VEGF-mediated and Notch-mediated signal pathways cross-regulate one another by mechanisms yet to be fully understood.

In these experiments, we evaluated the role of Notch receptor activation in angiogenesis using a novel soluble construct based on the extracellular domain of Notch1 (Notch1 decoy). In vitro, Notch1 decoy inhibited both ligand-induced activation of Notch signaling and morphogenesis of ECs adenovirally overexpressing Notch4. In vivo, Notch1 decoy reduced VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis in murine skin. Notch1 decoy expression delayed growth of murine Mm5MT xenografts in which Jagged1 expression was up-regulated by ectopic expression of FGF4 and disrupted vasculature and tumor viability in NGP neuroblastoma tumors. Taken together, these data support a requirement for Notch receptor function during neoangiogenesis, including VEGF-induced angiogenesis, and suggest that inhibition of this pathway may provide an effective new antitumor strategy.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and expression vectors

Compound E was purchased from Calbiochem, and PD166866 (14) was from Eisai Co., Ltd. Notch1 decoy encodes the rat Notch1 ectodomain (bp 241-4229, accession no. X57405) fused in frame to human IgG Fc. Retroviral pHyTC-Jagged1, pHyTC-Dll1, pHyTC-Dll4, and pBos-Notch1 have been described (15). Notch1 decoy and Fc were engineered into retroviral vector pHyTCX, and mouse FGF4 engineered into pQNCX. Adenoviral constructs encoding LacZ and mouse Notch4 and pAdlox-GFP have been described (16, 17).

Human umbilical vein ECs, adenoviral, and retroviral infections

Human umbilical vein ECs (HUVEC) were isolated as described (18), and mouse mammary carcinoma Mm5MT was obtained (American Type Culture Collection). We used adenovirus (Ad) at indicated multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) and retroviral supernatants from GP2-293 cells (BD Biosciences) for infection. HUVECs were selected using 300 μg/mL hygromycinB (Invitrogen), and Mm5MT transfectants expressing FGF4 (Mm5MT-FGF4) was selected in 1 mg/mL G418 (Life Technologies-Invitrogen) with double transfectants in 300 μg/mL hygromycinB. Both Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy and NGP-Notch1 decoy lines expressed Notch1 decoy, with protein detected in both cell lysates and in conditioned media (data not shown). Thus, a portion of Notch1 decoy is soluble in the extracellular environment.

Western blotting

Ad encoding Notch1 (Ad-Notch1) decoy-transduced HUVEC were cultured in endothelium serum-free medium (Life Technologies-Invitrogen) at 48 h and Mm5MT-FGF4 transfectants in DMEM. Western blots were performed using antihuman Fc (Pierce).

Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR. Mm5MT transfectants were cultured 7 d with vehicle or 1 μmol/L PD166866 [inhibitor of FGF receptor (FGFR) kinase], total RNA isolated (RNeasy mini-kit, Qiagen), and first-strand cDNA synthesized (SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System, Invitrogen). Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) for β-actin, FGF4, Hey1, VE-Cadherin, Jagged1, Dll1, and Dll4 (SYBER Green PCR Master Mix, 7300 Real-Time PCR; Applied Biosystems) was performed in triplicate, and values were normalized for β-actin. Values are shown for fold induction compared with controls (primer sequences available on request).

Coculture signaling assay

Notch1 decoy inhibition of ligand-induced signaling was performed as described (15). HeLa cells were transfected with 333 ng pBOS-Notch1, 333 ng pGA981-6 (19), and 83 ng pLNC-LacZ with either 666 ng pCMV-Fc or pHyTC-Notch1 decoy (333 ng for 1×, 666 ng for 2×). 293 cells were transfected with 680 ng pHyTc-Jagged1, pHyTc-Dll1, pHyTc-Dll4, or pHyTc-X (empty vector). Cells were harvested, luciferase activity was determined 48 h posttransfection (enhanced luciferase assay kit, BD PharMingen), and β-galactosidase activity was determined (Galacto-Light Plus kit, Applied Biosystems). Assays were performed in triplicate.

Endothelial coculture morphogenesis assay

HUVEC morphogenesis was assessed as described (15), modified by adding coculturing of Ad-Notch4–transduced HUVEC with Notch1 decoy-HUVEC or Fc-HUVEC transfectants. Ad-GFP at 10 m.o.i. was cotransduced in HUVECs with Ad-LacZ or Ad-Notch4 at 30 m.o.i. and, 48 h later, seeded on fibrin gels (24-well plates, 1.5 × 104 cells per well). Stable HUVEC-mock (HUVEC-X), HUVEC-Fc, or HUVEC-Notch1 decoy transfectants were seeded at 1.35 × 105 cells per well, and vehicle or 200 nmol/L compound E added 3 h later. Seven days later, HUVEC morphogenesis was calculated as the number of GFP-positive cells with processes compared with total GFP-positive cells per field.

Mouse dorsal air sac assay

The dorsal air sac (DAS) angiogenesis assay was performed as described (20) with minor changes. Millipore chambers were packed with 5.0 × 106 KP1/VEGF cells transduced (60 m.o.i.) with either Ad-GFP or Ad-Notch1 decoy and transplanted into the DAS of C57BL/6 mice (n = 3–5 each, with experiments performed in triplicate). Photographs were taken 4 d after implantation. To control for the effects of Notch1 decoy on growth of KP1 cells, we established that decoy expression did not affect growth of KP1 cells in culture (data not shown).

Colony formation (Clonogenic) assay

0.66% agar (250 μL; Agra noble, Difco) in DMEM (agar solution) was added into 24-well plates. After agar became solid, 250 μL of 1:1 mixture of agar solution and cell suspension were overlaid at 1.5 × 103 cells per well and kept at 4°C for 30 min and then 250 μL of agar solution was added again. DMEM (750 μL) was aliquoted into well and changed twice a week for 2 wk. Cell numbers were measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies). Data was shown as percentage of control compared with mock transfectants (Mm5MT-FGF4-X).

Mm5MT tumor model

Female C3H mice (6–8 wk old; Taconic) underwent s.c. implantation of 106 Mm5MT transfectants (n = 10 each). Tumor diameters were measured with calipers, and volume was calculated [length (mm) × width (mm)2 × ½]. Tumors were harvested at day 22 and analyzed. Experiments were performed thrice.

Immunohistochemistry

Fresh-frozen Mm5MT tissue sections (5 μm) were immunostained (see supplementary data for antibody list; ref. 21). CD31 quantitation was performed using an Eclipse E800 microscope and ImagePro Plus v.4.01. Twenty different fields per slide were measured, and density ratios were calculated as (area of specific staining)/(total area, each field). Data are shown as the ratio of the mean of average density ratios of each Mm5MT transfectant to Mm5MT mock-transfectant.

NGP tumor model

The NGP tumor model has previously been described in detail (22). NGP cells were transfected with LacZ or Notch1 decoy, as above, and 106 NGP-LacZ or NGP-Notch1 decoy cells implanted intrarenally in 4-wk-old to 6-wk-old NCR nude mice (Taconic; NGP-LacZ n = 11, NGP-Notch1 decoy n = 13). At 6 wk, tumors were harvested for analysis. Paraffin-embedded sections (5 μmol/L) were immunostained for CD-31/PECAM and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA). To detect apoptosis [terminal transferase deoxyuridine nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay], we used the Apoptag Red in situ kit (Chemicon). Signal was quantified by photographing 20 to 23 randomly selected fields of each tissue, excluding areas of normal kidney. Each frame was photographed in both red (TUNEL signal) and green channels. Using Adobe Photoshop, green channel signals were subtracted to eliminate erythrocyte autofluorescence. A uniform red-channel threshold was arbitrarily selected, and total signal area was measured in four NGP-Notch1 decoy and three NGP-LacZ tumors. Erythrocyte quantification was performed similarly.

Statistical analysis

Significance in quantitative studies was assessed using Tukey-Kramer tests (CD31 quantitation) and Kruskal-Wallis analysis (all others).

Results

Notch1 decoy inhibits ligand-induced Notch signaling in cells expressing Notch1

Notch1 decoy is based on the ectodomain of rat Notch1 fused to human IgG Fc (Fig. 1A) and is secreted, as determined by blotting of conditioned media from Ad-Notch1 decoy–infected HUVEC (Fig. 1B). We assessed Notch1 decoy activity using coculture signaling assays (15). 293 cells expressing Notch ligands, Jagged1, Dll1, or Dll4 activated Notch signaling when cultured with HeLa cells expressing Notch1, as measured by CSL-luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 1C). Expression of Notch1 decoy in either HeLa (Fig. 1C) or 293 cells (data not shown) blocked Notch1 signaling in coculture assays, indicating that this construct prevented Notch1 activation by Jagged1, Dll1, or Dll4 and, thus, is likely to function as a pan-ligand inhibitor of Notch1 signaling.

Figure 1.

Notch1 decoy inhibits activation of Notch signaling stimulated by Notch ligands. A, schematic of Notch1 decoy containing the 36 endothelial growth factor repeats of rat Notch1 fused to human Fc. B, Western blotting to detect secreted Notch1 decoy in conditioned medium from HUVECs transduced with Ad-Notch1 decoy at indicated m.o.i. Bar, 100 μm. C, Notch1 decoy inhibits ligand-induced CSL reporter activity in coculture signaling assay. Activation of Notch signaling was measured in HeLa cells expressing Notch1 cocultured with 293 cells expressing Notch ligands. Columns, mean; bars, SD. *, P < 0.05.

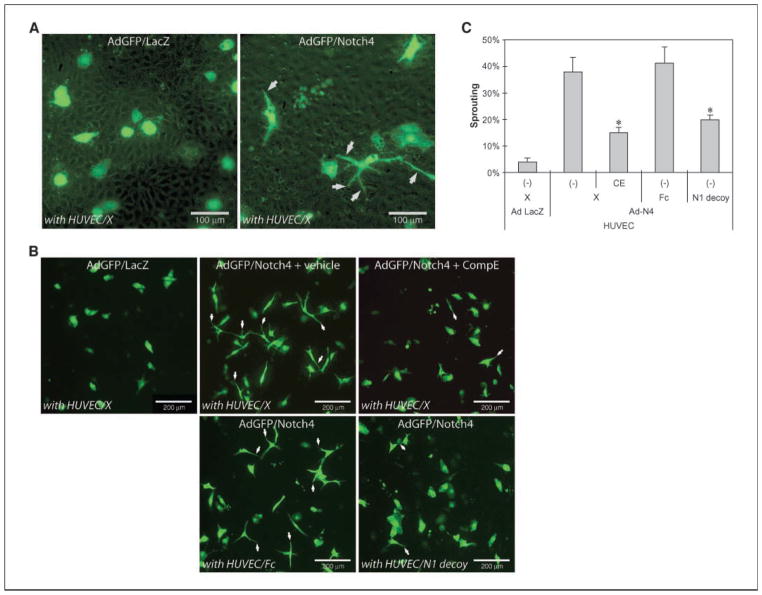

Notch1 decoy blocked morphogenesis of HUVEC induced by Notch4

HUVECs transduced with Notch4 formed cellular extensions when cocultured with control HUVECs on fibrin gels (Fig. 2A), resembling morphologic changes induced by VEGF and FGF2 (23, 24). Using a CSL-Notch reporter introduced into HUVEC, we found that ectopic Notch4 expression in HUVEC or ectopic Notch4/Dll4 coexpression can increase Notch signaling over basal signaling (Supplementary Fig. S1). Previous reports have shown that growth of ECs on fibrin induced Jagged1 expression, therefore, it is highly likely that Jagged1 was expressed in HUVECs grown on fibrin (25). In our assay, endogenous Notch ligands expressed by HUVECs may activate the exogenous Notch4 to promote formation of cellular extensions. We examined this possibility using either compound E, a γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI), or Notch1 decoy. Compared with vehicle, treatment with 200 nmol/L compound E clearly inhibited extensions in Notch4-HUVECs (Fig. 2B, top and Fig. 2C). Coculturing of Ad-Notch4 transduced HUVECs with Notch1 decoy–HUVEC transfectants similarly blocked endothelial extensions relative to Fc-HUVEC transfectants (Fig. 2B, bottom and Fig. 2C). Reduction in formation of cellular extensions was significant (Fig. 1D; P < 0.0001 for both compound E treatment and Notch1 decoy transduction; data shown as mean ± SD).

Figure 2.

Notch1 decoy or compound E blocks Notch4-mediated HUVEC extensions. A, ectopic expression of Notch4 induces morphogenetic changes by HUVECs cultured on fibrin gel. HUVECs were transduced with Ad-Notch4 at 30 m.o.i. and Ad-GFP at 10 m.o.i. to mark-infected cells. Two days later, HUVEC transfectants were cocultured with transduced HUVECs on fibrin gel and morphologic changes were documented using fluorescence microscopy. Notch4-induced cell extensions (right, white arrows). B, Notch inhibition blocks Notch4-mediated HUVEC extensions. Notch4 expression induced cell extensions (top center) compared with control LacZ expressing HUVEC (top left), whereas treatment with 200 nmol/L compound E blocked Notch4-induced extensions (top right). Notch1 decoy expression blocks Notch4-induced cell extensions. Adenovirus-transduced HUVECs were cocultured on fibrin gels with stable HUVEC transfectants expressing either Fc (bottom left) or Notch1 decoy (bottom right) and photographed 2 d later. Bar, 200 μm. C, quantification of effect of Notch signal inhibition on Notch4-induced extensions. Reduction in extensions was statistically significant after treatment with compound E and expression of Notch1 decoy (P < 0.0001, both). Columns, mean; bars, SD.

Collectively, these data indicate that Notch receptor activation seems to be involved and in part required to induce HUVEC extensions in this assay and that the Notch1 decoy functions similarly to GSI, further validating its activity as an inhibitor of multiple Notch ligand-receptor interactions.

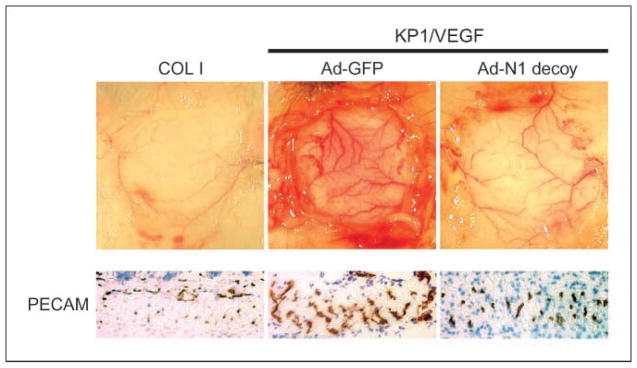

The Notch1 decoy inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis in murine dermis

The role of Notch in physiologic angiogenesis was evaluated using a DAS assay (26), in which a chamber containing VEGF-A121–expressing pancreatic KP1 tumor cells KP1 (KP1/VEGF121) is implanted under the dorsal skin of a mouse. Angiogenesis was induced in the dermal smooth muscle layer overlying the KP1/VEGF121 chamber (Fig. 3) but was significantly inhibited when KP1/VEGF121 cells also expressed Notch1 decoy (Fig. 3, top), as evidenced by immunostaining for the endothelial marker CD31/PECAM (Fig. 3, bottom). KP1/VEGF121 and Ad-GFP–infected KP1/VEGF121 cells elicit a similar angiogenic response (data not shown). These data suggest that dermal angiogenesis induced by VEGF requires Notch receptor activation. In this model, the Notch1 decoy is secreted from the cells in the implanted chamber and acts on vessels in adjacent tissue by diffusing out of the chamber as a soluble agent. To detect secreted Notch1 decoy, we immunostained for human Fc and found this deposited perivascularly and diffusely in tissues external to the implanted chamber (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 3.

Role of Notch signaling in VEGF-dependent in vivo angiogenesis. Inhibition of KP1/VEGF-induced angiogenesis with Notch1 decoy in mouse DAS assay. Representative photographs. Top, subcutaneous VEGF-induced angiogenesis with control COL1 (left) and KP1/VEGF cells transduced with GFP (middle) or with Notch1 decoy (right). Bottom, immunohistochemical analysis with CD31/PECAM antibody in muscle layer of skin (20×).

FGF4 induced the expression of Notch ligands, Jagged1, and Dll1, in mouse mammary tumor Mm5MT cells

Overexpression of FGF4 in Mm5MT cells promoted tumorigenicity in clonogenic and xenograft assays (data not shown). Because the tyrosine kinase pathway involving HGF/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling induced Jagged1 expression in HNSCC (10), we asked whether FGF4, via stimulation of tyrosine kinase signaling, would stimulate analogous expression of Notch ligands in Mm5MT cells. We detected up-regulation of Jagged1 and Dll1 in Mm5MT-FGF4 transfectants using quantitative PCR (Dll4 expression was unaltered; Fig. 4A). Immunoblotting confirmed up-regulation of Jagged1 protein in Mm5MT-FGF4 cells compared with control Mm5MT cells (Fig. 4B). The FGFR kinase inhibitor PD166866 (14) suppressed induction of both Jagged1 and Dll1 in Mm5MT-FGF4 transfectants (Fig. 4C), indicating that FGF4-induced Jagged1 and Dll1 expression requires FGFR signaling. We also evaluated the expression of several known angiogenic factors by quantitative RT-PCR, comparing Mm5MT-FGF4 cells to Mm5MT-FGF4 cells expressing Notch1 decoy. No major difference in the expression of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, placental growth factor, FGF1, FGF2, FGF4, platelet-derived growth factor-B, or angiopoietin 4 were detected when Mm5MT-FGF4 or Mm5MT-FGF4-Fc cells were compared with Mm5MT-FGF4 cells expressing Notch1 decoy (Supplementary Fig. S3A).

Figure 4.

FGF4 induces the expression of Notch ligands in murine mammary carcinoma Mm5MT cells. Stable Mm5MT transfectants generated by retroviral gene transfer. A, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression of Notch ligands showing induction of Jagged1 and Dll1 in Mm5MT-FGF4 compared with mock transfectants (Mm5MT-X). *, P < 0.05. B, Jagged1 protein is elevated in Mm5MT-FGF4 versus Mm5MT-X, as determined by Western blotting. C, reduction of Notch ligand expression in Mm5MT-FGF4 cells with PD166866, an inhibitor of FGFR kinase. *, P < 0.05. D, immunohistochemical analysis of Jagged1 staining in Mm5MT transfectants. Bar, 50 μm.

Notch1 decoy expression inhibited angiogenesis and growth of Mm5MT-FGF4 tumors in mice

Tumorigenicity of Mm5MT-FGF4 expressing Notch1 decoy was unaltered compared with Mm5MT-FGF4 cells or Mm5MT-FGF4 cells stably over-expressing Fc, as evaluated by a clonogenic assay in vitro (Fig. 5A). We hypothesized that Mm5MT-FGF4 tumors expressing Jagged1 would promote angiogenesis by signaling via endothelial Notch receptors. Thus, we evaluated the effect of Notch1 decoy expression on Mm5MT-FGF4 xenograft growth after s.c. implantation in mice. Immunostaining confirmed strikingly increased Jagged1 in Mm5MT-FGF4 tumors (Fig. 4D). In addition, Notch4 was detected in Mm5MT-FGF4 tumor endothelium (data not shown). Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy xenograft growth was significantly delayed compared with both Mm5MT-FGF4 mock and Fc transfectants, suggesting that Notch inhibition had impaired a critical element in tumorigenesis (Fig. 5B). Immunostaining for CD31/PECAM showed marked inhibition of angiogenesis in Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy tumors (Fig. 5C). Consistent with a requirement for Notch in vessel assembly, ECs appeared as detached solitary cells or small clusters, with few organized vessels detected. Quantitative analysis of anti-CD31 staining showed a 58% decrease in microvessel density in Notch1 decoy–expressing tumors (P < 0.001 for both Mm5MT-FGF4-X and Mm5MT-FGF4-Fc versus Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy; data shown as mean ± SD; Fig. 5D). Consistent with the immunohistochemical data, quantitative RT-PCR analyses of pooled tumor RNA revealed a 60% reduction in VE-Cadherin expression in the Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy tumors compared with the Fc control tumors (Supplementary Fig. S3B). Expression of Hey1, a direct target of Notch/CSL signaling in ECs, was decreased 2.7-fold in the Notch1 decoy–expressing tumors compared with controls (Supplementary Fig. S3C). Taken together, these data indicate that Notch1 decoy expression inhibited Notch signaling in tumors concurrent with a quantitative decrease in vasculature.

Figure 5.

Notch1 decoy inhibits angiogenesis and s.c. tumor growth of Mm5MT-FGF4 tumors in mice. A, Mm5MT-FGF4 tumor growth in soft agar is little affected by expression of Fc or N1 decoy. B, tumor volumes of Mm5MT-FGF4-X and Mm5MT-FGF4-Fc differ significantly from Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy transfectants in mice (**, day 21, P = 0.037 and P = 0.008, Mm5MT-FGF4-X and Mm5MT-FGF4-Fc versus Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy, respectively). Points, mean; bars, SD. C, immunohistochemical analysis of neovessels with CD31/PECAM staining within day 21 tumors derived from Mm5MT-FGF4 transfectants. Top, bar, 100 μm; bottom, bar, 50 μm. D, quantitative analysis showed a reduction in CD31(+) neovessels in Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy transfectants compared with Fc or mock-transfected tumors (*, P < 0.001 for both Mm5MT-FGF4-X and Mm5MT-FGF4-Fc versus Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy). Columns, mean; bars, SD.

The effects of Notch1 decoy on Mm5MT-FGF4 tumor angiogenesis we observed differed from previous reports of inhibition of the Notch ligand Dll4 in tumor xenografts, in which tumor growth was restricted concurrent with overgrowth of a dysfunctional tumor vessel network (8, 9). Therefore, to determine whether an overgrowth phase occurred in our system, we evaluated tumor vasculature at an earlier time point during Mm5MT-FGF4 tumor growth. The first evidence of reduction in Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy tumor growth (compared with Mm5MT-FGF4-X or Mm5MT-FGF4-Fc controls) is detectable at day 12. We quantitated tumor endothelium at this time point (day 12) but found no significant difference in PECAM-positive endothelium and no significant difference in the appearance of Dll4-positive tumor vessels when comparing control to Notch1 decoy–expressing tumors (Supplementary Fig. S4). We examined apoptosis in Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy tumors compared with Mm5MT-FGF4-X and Mm5MT-FGF4-Fc controls at both time points by TUNEL assay but no significant difference was identified (data not shown).

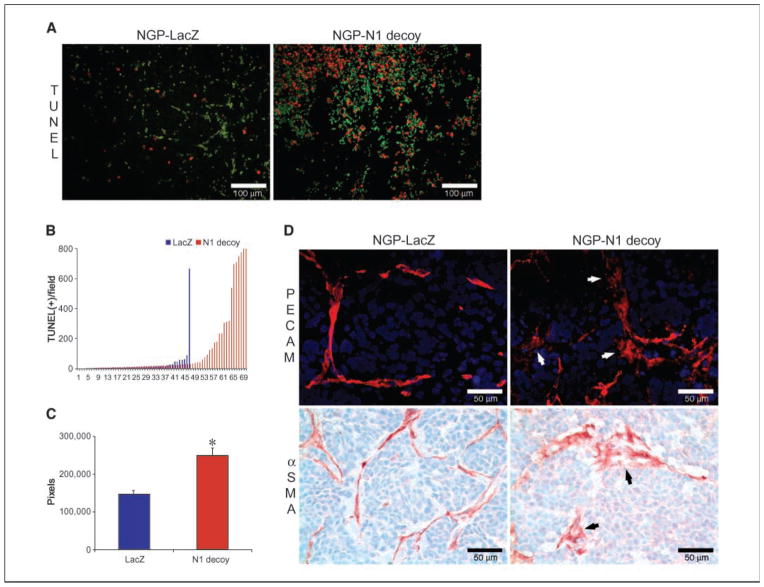

Notch1 decoy expression disrupted angiogenesis in human NGP neuroblastoma xenografts

NGP xenografts in mice form a mature hierarchical vasculature that is comparatively resistant to VEGF blockade (22). To determine whether Notch receptor activation contributed to NGP angiogenesis, we transfected NGP cells with Notch1 decoy, as above. To confirm the presence of Notch1 decoy, we immunostained tumor sections using antihuman Fc antibodies and detected signal both around the tumor cells and perivascularly (data not shown). Thus, Notch1 decoy may interact with multiple different cell types in tumor xenografts. Similar to results observed with Mm5MT-FGF4-Notch1 decoy cells, neither NGP cell proliferation in culture nor colony formation in soft agar was affected by expression of the Notch1 decoy (data not shown). However, xenograft viability was strikingly impaired (Fig. 6A), with significantly increased tumor cell apoptosis (P = 0.0002; TUNEL-positive cells in NGP-Notch1 decoy versus NGP-LacZ tumors; Fig. 6B). Intratumoral hemorrhage was significantly increased in NGP-Notch1 decoy tumors, suggesting that vessels were physically disrupted (P < 0.0001; Fig. 6C). Immunostaining for the vascular basement membrane component, collagen IV indicated an overall decrease in vasculature, with diminished branching, although remaining collagen sleeves seemed smooth and intact (not shown). However, immunostaining for ECs and vascular mural cells (VMC; using anti-CD31 and anti-αSMA antibodies, respectively) showed disorder of these normally contiguous cell layers. Individual vascular cells seemed irregular and were erratically detached from one another, with loss of vessel continuity (Fig. 6D). NGP tumor cells did not express Jagged-1, although immunostaining showed expression in vasculature (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that Notch1 decoy expression disrupted Notch-mediated endothelial and VMC interactions in tumor vasculature, leading to instability, hemorrhage, and defective perfusion of tumor tissues.

Figure 6.

Notch1 decoy expression disrupts angiogenesis and impairs tumor viability in human NGP xenografts. We have previously reported that human neuroblastoma xenografts in mice have a mature, hierarchical vasculature that is relatively resistant to VEGF blockade (22). To determine whether Notch receptor activation contributed to NGP angiogenesis, we transfected NGP cells with the Notch1 decoy construct, which did not affect their ability to grow in culture (data not shown). There was, however, a marked decrease in tumor viability in vivo (A; red fluorescence, TUNEL; green fluorescence, erythrocytes; bar, 100 μm), with significantly increased fields that had high levels of tumor cell apoptosis [B; P = 0.0002; TUNEL-positive cells in NGP-Notch1 decoy (

) versus NGP-LacZ (

) versus NGP-LacZ (

) tumors], and increased intratumoral hemorrhage [C; *, P < 0.0001, quantitation of parenchymal erythrocyte signal, NGP-Notch1 decoy (

) tumors], and increased intratumoral hemorrhage [C; *, P < 0.0001, quantitation of parenchymal erythrocyte signal, NGP-Notch1 decoy (

) versus NGP-LacZ (

) versus NGP-LacZ (

) tumors]. In addition, the tumor vessel networks in NGP-Notch1 decoy xenografts seemed to have been physically disrupted compared with NGP-LacZ controls, with immunostaining for ECs and VMCs (using anti-CD31/PECAM and αSMA antibodies, respectively) demonstrating lack of continuity of these vascular cell layers (D; bar, 50 μm). Individual vascular cells seemed detached from one another. Taken together, these results suggest that Notch1 decoy expression disrupted the ability of ECs and VMCs to form stable vascular conduits, causing vessel breakdown, hemorrhage, and ischemia of tumor tissues.

) tumors]. In addition, the tumor vessel networks in NGP-Notch1 decoy xenografts seemed to have been physically disrupted compared with NGP-LacZ controls, with immunostaining for ECs and VMCs (using anti-CD31/PECAM and αSMA antibodies, respectively) demonstrating lack of continuity of these vascular cell layers (D; bar, 50 μm). Individual vascular cells seemed detached from one another. Taken together, these results suggest that Notch1 decoy expression disrupted the ability of ECs and VMCs to form stable vascular conduits, causing vessel breakdown, hemorrhage, and ischemia of tumor tissues.

Discussion

Recent reports confirm the critical role of the Notch ligand Dll4 in angiogenesis and show that Dll4 blockade can effectively repress tumor growth by deregulating vascular development (8, 9). In this study, we show that blockade of Notch receptor function using a novel secreted construct derived from the Notch1 ectodomain effectively inhibits angiogenesis. The Notch1 decoy inhibited ligand-dependent Notch1 signal activation induced by ligands Jagged1, Dll1, and Dll4. Thus, Notch1 decoy likely acts to block multiple distinct ligand receptor combinations that participate in physiologic or pathologic angiogenesis. Consistent with a role for Notch receptor activation in neoangiogenesis, overexpression of Notch4-induced EC extensions, which could be prevented by blocking Notch signaling with either Notch1 decoy or GSI. Similarly, diffusion of Notch1 decoy from an implanted chamber reduced VEGF-stimulated angiogenesis in the dermis. Although Notch1 decoy did not inhibit tumor cell growth in vitro, expression of Notch1 decoy inhibited growth and angiogenesis of Mm5MT-FGF4 xenografts, in which Jagged1 expression is up-regulated. Similarly, Notch1 decoy expression had no effect on NGP tumor cell proliferation in vitro but disrupted tumor vessels and viability in vivo.

Overall, the effects of Notch1 decoy on dermal and tumor angiogenesis in these studies are distinct from those previously reported for Dll4 blockade in tumors. Most notable among these differences is the lack of observable overgrowth of endothelium in response to Notch1 decoy expression observed in all three of the in vivo angiogenesis models we used. In the Mm5MT-FGF4 model, evaluation of both early (day 12) and later (day 21) time points for tumor evaluation showed either equivalent (day 12) or reduced (day 21) EC content. Similarly, in the NGP tumor model, Notch1 decoy expression resulted in vascular disruption, without evidence of overgrowth. It is thus clear that response to Notch1 decoy expression is unique, likely reflecting the interruption of multiple Notch ligand–receptor interactions acting on endothelium as opposed to the effects observed after the selective inhibition of Dll4.

Notch4 overexpression in HUVECs was sufficient to induce endothelial extensions on fibrin gel without exogenous expression of Notch ligands (Fig. 2). Because fibrin is known to induce Jagged1 expression in EC and, thus, may have functioned to promote HUVEC expression of Jagged1 in this assay, we speculate that this caused activation of Notch4; in reporter assays, increased Notch activity was found when HUVECs engineered to express Dll4 and Notch4 were cocultured, suggesting that paracrine signaling is responsible for enhanced Notch signaling. In HeLa coculture signaling assays, the Notch1 decoy inhibited signaling via ligand-Notch1 receptor interaction. We were unable to similarly evaluate Notch4 activity, as Notch4 was poorly processed and presented on the surface of HeLa cells (data not shown). However, processed Notch4 is found on HUVECs after adenoviral Notch4 transduction (not shown), indicating that Notch1 decoy can block ligand-induced Notch4 activation (27).

Expression of the Notch1 decoy also blocked new vessel growth stimulated by VEGF121 in the dermis, consistent with previous work demonstrating that Notch receptor activation is required for VEGF-induced up-regulation of target genes (28). One of these endothelial target genes is Dll4, which acts to reduce VEGFR2 and neuropilin-1 expression in a negative feedback loop (12). As above, inhibition of Dll4 disrupts this loop and results in deregulated sprouting, forming a nonfunctional vasculature (8, 9). However, Notch1 decoy expression exerts a different effect, repressing neoangiogenesis, potentially reflecting disruption of other Notch ligand: receptor interactions (e.g., Jagged1/Notch1, as discussed below). Taken together, these data suggest a model in which construction of a vessel network is exquisitely regulated by crosstalk between Notch and VEGF pathways at multiple points, with different Notch receptor and ligand pairs playing distinct roles in this process.

The multiple roles recently shown for Notch signaling in tumorigenesis increase the attractiveness of this pathway as a potential target for cancer therapy. Whereas Notch activation is likely to function directly in malignant transformation in human cancers (29, 30), it seems to be required for angiogenesis in a number of tumor systems (8, 9) and in our models presented here. Interestingly, Notch ligand induction can be regulated by growth factor signals. For example, Jagged1 is induced in tumor cells by HGF (10) and Dll4 induced in ECs by VEGF (11). Here, we show that FGF4 can similarly stimulate Jagged1 and Dll1 expression in murine Mm5MT cells. Notch1 decoy reduced Mm5MT-FGF4 tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo but did not affect tumorigenicity in vitro. Similarly, expression of Notch1 decoy did not affect NGP tumor growth in vitro while strikingly disrupting NGP vasculature in vivo. Thus, these results suggest that Notch receptor activation in Mm5MT and NGP vessels rather than tumor cells is required for neoplastic growth in these neoplasms.

While both Mm5MT-FGF4 and NGP xenografts displayed striking disorder of tumor vasculature after Notch1 decoy expression, the differences in vascular phenotype observed in these models suggest that tumor-specific patterns of Notch ligand/receptor interaction may fine-tune vessel assembly. Mm5MT-FGF4 tumors strongly express Jagged-1, proliferate rapidly, and develop dense, erratic endothelial networks relatively devoid of recruited VMCs. Consistent with previous data indicating that tumor cell expression of Jagged-1 can stimulate Notch-dependent angiogenesis (10), Notch1 decoy expression caused profound ablation of Mm5MT-FGF4 vasculature by day 21, leaving small clusters or individual ECs isolated in tumor parenchyma. In contrast, NGP tumors developed a mature vascular plexus, with near-uniform coverage of endothelium by VMCs. Also in contrast to the Mm5MT-FGF4 model, NGP vessels strongly expressed Jagged-1, whereas NGP tumor cells did not. Notch1 decoy expression in NGP tumors causes intratumoral hemorrhage and necrosis, with loss of vessel continuity. We speculate that the strikingly different patterns of Jagged-1 expression in the Mm5MT-FGF4 and NGP models (tumor cell versus EC) may contribute to the distinct effects of the Notch1 decoy in each. For example, engagement of Jagged-1 expressed by Mm5MT-FGF4 tumor cells by endothelial Notch receptors may be required for new tumor vessels to sprout. Notch1 decoy expression disrupted this interaction and limited new tumor growth. In contrast, NGP vessels may be stabilized by Notch-mediated signaling between adjacent vascular cells, so that Notch1 decoy caused discontinuity in already-formed vessels with loss of tumor perfusion.

Collectively, these data provide support for a model in which Notch signaling controls interactions between the multiple cell types responsible for tumor angiogenesis. Whereas Notch activation is broadly required for new vessel formation, tumor and vascular cell expression of individual Notch proteins may differentially regulate vascular sprouting and remodeling. Our results confirm the importance of Notch ligand receptor interactions in tumor vasculature and suggest that perturbing Notch receptor function may provide a novel and effective means of disrupting tumor angiogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NIH grants 5RO1HL62454 (J.K. Kitajewski), 5R01CA100451 (J.J. Kandel), R01CA088951 (D.J. Yamashiro), K08CA107077 (J. Huang), and 5K01DK744629 (C.J. Shawber); Department of Defense grant W81XWH-07-1-0362 (J.K. Kitajewski); Children’s Neuroblastoma Cancer Foundation (S. Huang, D.J. Yamashiro); and Taybandz, Inc. (D.J. Yamashiro).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Research Online (http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interest in this work.

We dedicate this work to the memory of Dr. Judah Folkman.

References

- 1.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain R, Duda D, Clark J, Loeffler J. Lessons from phase III clinical trials on anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:24–40. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopan R. Notch: a membrane-bound transcription factor. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1095–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.6.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shawber C, Kitajewski J. Notch function in the vasculature: insights from zebrafish, mouse and man. Bioessays. 2004;26:225–34. doi: 10.1002/bies.20004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gale NW, Dominguez MG, Noguera I, et al. Haploinsufficiency of δ-like 4 ligand results in embryonic lethality due to major defects in arterial and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15949–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407290101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel NS, Li J-L, Generali D, Poulsom R, Cranston DW, Harris AL. Up-regulation of Delta-like 4 ligand in human tumor vasculature and the role of basal expression in endothelial cell function. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8690–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel NS, Dobbie MS, Rochester M, et al. Up-regulation of endothelial Delta-like 4 expression correlates with vessel maturation in bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4836–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridgway J, Zhang G, Wu Y, et al. Inhibition of Dll4 signalling inhibits tumour growth by deregulating angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;444:1083–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noguera-Troise I, Daly C, Papadopoulos NJ, et al. Blockade of Dll4 inhibits tumour growth by promoting non-productive angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;444:1032–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng Q, Li S, Chepeha DB, et al. Crosstalk between tumor and endothelial cells promotes tumor angiogenesis by MAPK activation of Notch signaling. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Z-J, Shirakawa T, Li Y, et al. Regulation of Notch1 and Dll4 by vascular endothelial growth factor in arterial endothelial cells: implications for modulating arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:14–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.14-25.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams CK, Li JL, Murga M, Harris AL, Tosato G. Up-regulation of the Notch ligand Delta-like 4 inhibits VEGF-induced endothelial cell function. Blood. 2006;107:931–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shawber CJ, Funahashi Y, Francisco E, et al. Notch alters VEGF responsiveness in human and murine endothelial cells by direct regulation of VEGFR-3 expression. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3369–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI24311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panek RL, Lu GH, Dahring TK, et al. In vitro biological characterization and antiangiogenic effects of PD 166866, a selective inhibitor of the FGF-1 receptor tyrosine kinase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:569–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das I, Craig C, Funahashi Y, et al. Notch oncoproteins depend on {γ}-secretase/presenilin activity for processing and function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30771–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shawber CJ, Das I, Francisco E, Kitajewski JAN. Notch signaling in primary endothelial cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;995:162–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy S, Kitamura M, Harris-Stansil T, Dai Y, Phipps ML. Construction of adenovirus vectors through Cre-lox recombination. J Virol. 1997;71:1842–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1842-1849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaffe E, Nachman R, Becker C, Minick C. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:2745–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato H, Sakai T, Tamura K, et al. Functional conservation of mouse Notch receptor family members. FEBS Lett. 1996;395:221–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Funahashi Y, Wakabayashi T, Semba T, Sonoda J, Kitoh K, Yoshimatsu K. Establishment of a quantitative mouse dorsal air sac model and its application to evaluate a new angiogenesis inhibitor. Oncol Res. 1999;11:319–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vorontchikhina MA, Zimmermann RC, Shawber CJ, Tang H, Kitajewski J. Unique patterns of Notch1, Notch4 and Jagged1 expression in ovarian vessels during folliculogenesis and corpus luteum formation. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5:701–9. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim ES, Serur A, Huang J, et al. Potent VEGF blockade causes regression of coopted vessels in a model of neuroblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11399–404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172398399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montesano R. Phorbol esters induce angiogenesis in vitro from large-vessel endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1987;130:284–91. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041300215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koolwijk P, van Erck MG, de Vree WJ, et al. Cooperative effect of TNFα, bFGF, and VEGF on the formation of tubular structures of human microvascular endothelial cells in a fibrin matrix. Role of urokinase activity. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:1177–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimrin AB, Pepper MS, McMahon GA, Nguyen F, Montesano R, Maciag T. An antisense oligonucleotide to the notch ligand jagged enhances fibroblast growth factor-induced angiogenesis In vitro. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32499–502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funahashi Y, Wakabayashi T, Semba T, Sonoda J, Kitoh K. Establishment of a quantitative mouse dorsal air sac model and its application to evaluate a new angiogenesis inhibitor. Oncol Res. 1999;11:319–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shawber CJ, Das I, Francisco E, Kitajewski J. Notch signaling in primary endothelial cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;995:162–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hainaud P, Contreres JO, Villemain A, et al. The role of the vascular endothelial growth factor-Delta-like 4 ligand/Notch4-ephrin B2 cascade in tumor vessel remodeling and endothelial cell functions. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8501–10. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nickoloff B, Osborne B, Miele L. Notch signaling as a therapeutic target in cancer: a new approach to the development of cell fate modifying agents. Oncogene. 2003;22:6598–608. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radtke F, Raj K. The role of notch in tumorigenesis: oncogene or tumour suppressor? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:756–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.