Abstract

Following reinnervation of denervated rat tail arteries, nerve-evoked contractions are at least as large as those evoked in normally innervated arteries despite a much lower nerve terminal density. Here nerve-evoked contractions have been investigated after transection of half the sympathetic innervation of normal tail arteries. After 1 week, the noradrenergic plexus 50–70 mm along the tail was about half as dense as control. Excitatory junction potentials recorded in smooth muscle cells of arterial segments isolated in vitro were half their normal amplitude. Surprisingly, nerve-evoked contractions of isometrically mounted segments were not reduced in amplitude, as was also the case after only 3 days. After 1 week, enhancement of nerve-evoked contractions by blocking either neuronal re-uptake of noradrenaline with desmethylimipramine or prejunctional α2-adrenoceptors with idazoxan was similar to control, suggesting that these mechanisms are matched to the number of innervating axons. The relative contribution of postjunctional α2-adrenoceptors to contractions evoked by long trains of stimuli was enhanced but that of α1-adrenoceptors was unchanged. Transiently, sensitivity to the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine was slightly increased. After 7 weeks, amplitudes of nerve-evoked contractions remained similar to control, and sensitivity to phenylephrine had recovered but that to the α2-adrenoceptor agonist clonidine was slightly raised. The normal amplitude of nerve-evoked contractions after partial denervation is only partly explained by the greater contribution of α2-adrenoceptors. While the post-receptor mechanisms activated by nerve-released transmitter may be modified to amplify the contractions after partial denervation, our findings suggest that these mechanisms are normally saturated, at least in this artery.

Key points

To test whether the responses of the normal rat tail artery to supramaximal nerve stimulation depend on activating all of its innervation, half the sympathetic innervation was surgically removed (partial denervation, PD).

After PD, the amplitude of excitatory junction potentials was halved but the amplitudes of contractions of isolated segments of PD arteries were of normal amplitude.

The effects of α2-adrenoceptor mediated auto-inhibition of noradrenaline release and prejunctional re-uptake of released noradrenaline were not reduced after PD.

The normal contraction amplitude could not be explained by upregulation of junctional or extra-junctional adrenoceptors after PD, although slightly increased α2-adrenoceptor sensitivity prolonged contraction duration, amplifying responses during continuous stimulation.

A surprising conclusion is that post-receptor mechanisms activated by noradrenaline released from sympathetic nerves are normally saturated. If this applies to other arteries, it significantly changes understanding of their control by sympathetic nerves.

Introduction

Most current knowledge of vascular contraction arises from studies involving application of exogenous transmitter substances (Guimaraes & Moura, 2001; Docherty, 2010), which activate purinoceptors and adrenoceptors expressed throughout the muscle (Hansen et al. 1999; Methven et al. 2009b). However, where investigated, the actions of nerve-released noradrenaline (NA) in arteries have differed from those of exogenously applied NA (Yang & Chiba, 2001; Townsend et al. 2004; Zacharia et al. 2004; Wier et al. 2009). When the sympathetic nerves are activated, NA and ATP are released from a proportion of the varicose nerve terminals that form neuromuscular junctions on the outermost smooth muscle cells (Brock & Cunnane, 1993; Luff et al. 1995). Neural activation occurs via punctate high concentrations of NA, which interact with discrete populations of ‘junctional’ receptors and readily diffuse away, the majority being cleared via the neuronal NA transporters (NATs) and the rest being removed by extraneuronal uptake or escape into the vasculature (Eisenhofer, 2001). This situation contrasts with the steady-state concentrations of exogenous NA that can diffuse through the media to activate all adrenoceptor populations. While a standing concentration of NA may build up in the perivascular space during ongoing nerve activity (such as in vivo), whether this reaches concentrations that activate ‘extrajunctional’ adrenoceptors has not been proven.

In isolated arterial segments, electrical stimuli of increasing strength progressively increase the contractile response until a maximum is reached (e.g. Yeoh et al. 2004a); this is interpreted as being due to progressive recruitment of the population of perivascular sympathetic axons (Bell, 1969; Hirst, 1977). In most arterial vessels studied so far, NA appears to be the predominant transmitter involved in evoking constriction as responses to nerve stimulation are substantially reduced by α-adrenoceptor blockade (e.g. Yang & Chiba, 2001; Townsend et al. 2004; Yeoh et al. 2004b; Zacharia et al. 2004; Rummery et al. 2010). In the rat tail artery, blockade of purinoceptors does not affect contractions evoked by low-frequency nerve stimulation, which are almost completely abolished by α-adrenoceptor antagonists (Yeoh et al. 2004b; Al Dera et al. 2012). However, neuropeptide Y (NPY) co-released on nerve activation may play a role in potentiating the noradrenergic contractions in the tail artery (Duckles et al. 1997; Bradley et al. 2003).

Although these functional properties have been characterised, most molecular details of the neurovascular relationship remain unresolved. The sites of NA release (whether from non-contacting varicosities as well as neuromuscular junctions), the cellular distribution of NATs on perivascular axons, the location of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors accessed by nerve-released NA (pre- and postjunctional and extrajunctional), and the mechanisms by which Ca2+ levels are elevated in response to nerve-released neurotransmitter all await further experimentation. The limitations to localisation include the complex neurovascular architecture (Luff et al. 1995) and the lack of specific antibodies to any subtype of α-adrenoceptor (Jensen et al. 2009). For example, binding of fluorescent α1-adrenoceptor ligands has revealed their sparse and uneven distribution over arterial muscle cells (Methven et al. 2009a; Daly et al. 2010), with a large proportion of receptors being intracellular (McGrath et al. 1999), and their expression by endothelial and adventitial cells as well as on nerve bundles (Daly et al. 2010). These findings emphasise how little information tissue receptor expression measurements would provide.

There are, however, pharmacological tools that can be used to analyse neurovascular transmission. We have recently used this approach in isolated rat arteries to examine contractions evoked by perivascular stimulation with trains of low-frequency stimuli or brief high-frequency bursts in the physiological range (Jänig, 2006) after disruption of the sympathetic innervation (e.g. Yeoh et al. 2004a,b; Brock et al. 2006; Tripovic et al. 2010). The consequences of reinnervation of denervated tail arteries (Tripovic et al. 2011) were surprising. These studies demonstrated that: (1) sympathetic reinnervation of denervated arteries is incomplete for many months and they remain hyperreactive to agonists that are substrates of NATs; and (2) despite a much lower density of noradrenergic axons, nerve-evoked contractions recover to control amplitude. The latter finding was the most unexpected. Apparently either the effectiveness of neurotransmitter(s) released from the regenerated axon terminals is enhanced or there is substantial redundancy in the normal vascular innervation.

Here we tested the hypothesis that the vasoconstriction to supramaximal sympathetic nerve stimulation depends on activating all of its innervation, as has always been assumed from the response to graded stimuli (see above). The anatomical arrangement of the sympathetic innervation of the rat tail artery provides a unique opportunity to remove half of the noradrenergic axons surgically without interfering with the artery directly (for details see Methods). The artery is located in the ventral midline and is innervated from both sides of the sympathetic chain (see Sittiracha et al. 1987). We have examined several characteristics of neurovascular transmission in this artery with and without transection of half its innervation, using histochemistry to check the distribution of perivascular noradrenergic terminals, electrophysiological techniques to record membrane potential in the vascular smooth muscle cells and myography to record isometric tension. Contractile responses to supramaximal electrical stimulation of short segments of the artery isolated in vitro have been studied 1 and 7 weeks after the lesion and the effects on the responses of pharmacological manipulation of pre- and postjunctional α-adrenoceptors and blockade of re-uptake of released NA have been analysed. In addition, concentration–response curves for exogenous α1- (phenylephrine (PE), methoxamine) and α2- (clonidine) adrenoceptor agonists have been generated to test the sensitivity of the vascular smooth muscle. The surprising finding was that, as in reinnervated tail arteries, maximal contractile responses to perivascular stimulation were similar to control when only half the innervation was present.

Methods

All experimental procedures conformed to the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes and were approved by the University of New South Wales Animal Care and Ethics Committee.

Innervation of the rat tail artery

The innervation of the rat tail artery is derived from postganglionic cell bodies lying within lower sacral and coccygeal paravertebral ganglia, which send their axons to reach the artery via two ventral and two dorsal collector nerves that run the length of the tail. Segmental branches from these nerves run distally for 30–40 mm before reaching the artery and supply a region of the vessel that extends up to 10 mm distal of the point where they first make contact (Sittiracha et al. 1987). Transecting all four collector nerves 10 mm proximal to the base of the tail produces complete denervation of the artery below ∼50 mm distally (Tripovic et al. 2010). The artery in the proximal 100 mm of the tail receives all its innervation, which consists of many sympathetic axons and very rare peptidergic sensory axons (Li & Duckles, 1993), via the two ventral collector nerves (VCNs; see Sittiracha et al. 1987). Transection of only one VCN proximal to the base of the tail therefore removes half of the innervation of the artery from 50 to 100 mm along the tail.

Surgical procedures

Female Wistar rats (7–8 weeks of age) were anaesthetised with ketamine/xylazine (60 and 10 mg kg−1 i.p.). The VCN on the left side of the tail was exposed via a lateral incision ∼10 mm proximal to the base of the tail and just behind the hip joints. The nerve was mobilised and lifted briefly out of its groove, then cut and 3–5 mm of nerve trunk removed. After dusting with oxytetracycline powder, the wound was closed using Michel clips. The animals recovered uneventfully and were maintained for 1 week (7 ± 1 (mean ± SD) days, n= 13) or 7–8 weeks (51 ± 2 days, n= 8) postoperatively. One week was selected to avoid any possible effects of releasing NA from the degenerating axon terminals, which can take up to 5 days to be removed 60–75 mm from the lesion site where the tissue responses were measured (Cragg, 1965; Andres et al. 1985). Seven weeks was selected to allow for stabilisation of longer term changes in postjunctional sensitivity to agonists that are known to occur following denervation (Tripovic et al. 2010). Some of the experiments were also repeated in animals only 3 days after the lesion (n= 7). In sham-operated animals, the nerve was mobilised and lifted briefly out of its groove but not cut; these animals were maintained for 1 week (8 ± 2 days, n= 7) or ∼8 weeks (55 ± 3 days, n= 8). Age-matched naïve rats (n= 15) were used to confirm that the sham operation did not change nerve-evoked contractions of the tail artery. For histological experiments to confirm the initial extent of denervation, we used rats 5–6 days after cutting one (n= 3) or both VCNs (n= 5) and for these we used age-matched naïve rats as controls.

Experimental preparations

The animals were killed by exsanguination under deep anaesthesia (pentobarbitone 100 mg kg−1, i.p.) and the tail artery from 50 to 65 mm along the tail was removed for myography studies. The isolated arterial segments were placed in physiological saline of the following composition (in mm): 150.6 Na+, 4.7 K+, 2 Ca2+, 1.2 Mg2+, 144.1 Cl−, 1.3 H2PO4−, 16.3 HCO3− and 7.8 glucose. This solution was bubbled with carbogen gas (95% O2, 5% CO2) and maintained at 36–37°C. In lesioned animals, ∼10 mm segments of artery from immediately above and below the region used for myography studies (50–65 mm along the tail) were removed for histological assessment of the innervation.

Recordings of membrane potential

Segments of tail artery from between 50 and 65 mm distal to the base of the tail were pinned to the Sylgard- (Dow-Corning Midland, MI, USA) coated base of a 1 ml recording chamber and continuously superfused (4 ml min−1) with physiological saline. The perivascular nerves were electrically activated with supramaximal stimuli (1 ms pulse width, 20 V) via a suction-stimulating electrode into which ∼5 mm of the proximal end of the artery segment was drawn. Intracellular recordings were made from smooth muscle cells located 1–2 mm distal from the mouth of the stimulating electrode using sharp glass microelectrodes filled with 0.5 m KCl (120–180 MΩ) and connected to an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Inc. Foster City, CA, USA). To avoid recording excitatory junction potentials (EJPs) in cells lying close to neuromuscular junctions at the adventitial–medial border, which are characterised by an early fast component, impalements were made from cells located deeper in the media in which EJPs decayed monoexponentially, reflecting the electrical behaviour of the smooth muscle syncytium (Cassell et al. 1988). Impalements were only accepted if the following criteria were satisfied: (1) the cell penetration was abrupt, (2) the membrane potential increased to a value more negative than the initial potential and (3) the membrane potential was stable for ∼5 min before recording. Resting membrane potentials were determined upon abrupt withdrawal of the microelectrode. Recordings were made from 5–6 cells in each tissue.

Mechanical responses

Eight arterial ring segments (∼1.5 mm long) from 50–70 mm along the tail were mounted isometrically between stainless steel wires (50 μm diameter) in two four-chamber myographs (Multi Myograph Model 610M, Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark). Each chamber of the myographs contained 6 ml of physiological saline that was exchanged at regular intervals throughout the recording period. The lengths (1.45 ± 0.15 mm (mean ± SD), range 1–1.75 mm) and lumen diameters (see Results) of the segments varied. To normalise the basal conditions, Laplace's equation was used as previously reported (see Tripovic et al. 2011). The reported lumen diameters were estimated from the measured internal circumference after completion of this normalisation procedure (see Mulvany & Halpern, 1977). The contractions to electrical stimulation and to agonists were measured as increases in wall tension (force/2× artery segment length; see Mulvany & Halpern, 1977).

Electrical stimulation

Four artery segments were used to assess contractions to activation of the perivascular nerves. Electrical stimuli (0.2 ms pulse width, 20 V) were applied through platinum plate electrodes mounted on either side of the artery along its length. In preliminary experiments, these stimuli produced supramaximal responses that were abolished by 0.5 μm tetrodotoxin, indicating that the electrically evoked contractions were due to action potential-evoked release of neurotransmitters from the perivascular nerves.

Initially, frequency–contraction curves were performed for each artery segment. The artery segments were stimulated with single trains of 25 stimuli at 0.1, 0.3, 0.5 and 1 Hz, with each train separated by a 4 min interval. Following generation of the frequency–contraction curves, the arteries were stimulated with repeated cycles of stimulation composed of single trains of 10 stimuli at 1 Hz and 10 Hz, and 100 stimuli at 1 Hz, each separated by a 4 min interval. Each cycle lasted approximately 14 min.

Blockade of pre- versus postjunctional α-adrenoceptors

Different patterns of stimulation were used to assess possible changes in α2-adrenoceptor-mediated autoinhibition of NA release after partial denervation (PD) and the contribution to nerve-evoked contractions of postjunctional α1- and α2-adrenoceptors on the vascular smooth muscle. As the component of contraction due to activation of postjunctional α2-adrenoceptors is slow, peaking ∼10 s after a stimulus (Bao et al. 1993), the peak amplitude of contractions to short high-frequency (HF) trains of 10 pulses at 10 Hz (∼2 s after starting stimulation) reflects activation of postjunctional α1-adrenoceptors alone. Therefore, the facilitatory effect of blocking α2-adrenoceptors on contractions to these short HF trains was used to evaluate α2-adrenoceptor-mediated autoinhibition of NA release.

In contrast, activation of postjunctional α1- and α2-adrenoceptors contributes to contractions evoked by low-frequency trains of 10 and 100 pulses at 1 Hz (Bao et al. 1993, Yeoh, 2004b; Yeoh et al. 2004a; Tripovic et al. 2011). Two of the artery segments were used to assess the effects of α1- and α2-adrenoceptor subtype selective antagonists on nerve-evoked contraction. Following the fifth cycle of stimulation, one of the artery segments was treated with the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin (10 nm, Sigma Aldrich Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia), and the other with the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist idazoxan (0.1 μm, Sigma Aldrich). Following the seventh stimulation cycle, the other adrenoceptor antagonist was added so that the arteries were exposed to a combination of prazosin and idazoxan. In the presence of each drug or combination of drugs, data from the second cycle of stimulation were used to assess their effects.

Blockade of axonal NA re-uptake by NATs

The other two artery segments were used to assess the effects of blocking NATs with desmethylimipramine (DMI; 30 nm, Sigma Aldrich). This drug was added following the third cycle of stimulation, with the magnitude of the DMI-induced enhancement of contraction amplitude determined as the ratio of amplitudes recorded during the fifth cycle of stimulation (in DMI) to those recorded during the third cycle of stimulation (i.e. in control solution). Following the fifth stimulation cycle, both prazosin and idazoxan were added to confirm that the contractions were largely mediated by NA.

Concentration–contraction curves

The remaining four artery segments were used to construct non-cumulative concentration–contraction curves for the α1-adrenoceptor agonists PE (0.01–30 μm, Sigma Aldrich) and methoxamine (0.01–30 μm, Sigma Aldrich), and the α2-adrenoceptor agonist clonidine (0.001–3 μm, Sigma Aldrich). One artery segment was used for each of these agonists and was exposed to each concentration for 5 min, followed by a washout period during which the tension returned to the baseline value before addition of the next concentration of agonist. In the case of PE, concentration–contraction curves were obtained in pairs of artery segments, one in the absence and the other in the presence of the NAT inhibitor DMI (30 nm) because this agonist, unlike methoxamine, is a substrate for the NAT (Trendelenburg et al. 1970). This concentration of DMI produces a maximal leftward shift in the PE concentration–response curve in normally innervated arteries (see Tripovic et al. 2010).

Depolarisation of vascular muscle

To test the ability of the vascular smooth muscle to contract, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels were opened by depolarisation. Following completion of the concentration–response curves, contractions to physiological saline containing 60 mm K+ (equimolar substitution of K+ for Na+, produces ∼60% of maximum force in control tissue) were recorded in the presence of the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin (0.01 μm) and the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist idazoxan (0.1 μm) to inhibit the actions of any NA released by depolarisation of the sympathetic nerves.

Immunohistochemistry

Artery segments taken from 10–20, 40–50 and ∼70 mm along the tail were fixed at their in vivo length overnight in Zamboni's fixative, washed and infiltrated with 30% sucrose. Each piece of experimental tissue was processed at the same time as that of corresponding tissue from control animals. Longitudinal cryostat sections (20 μm thick) were cut, permeabilised with 50% ethanol and incubated at room temperature overnight in mouse monoclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (ImmunoStar Inc, Hudson, WI, USA), then washed and incubated for 2 h in CY3-labelled donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc., Baltimore, PA, USA) at room temperature in the dark. Immunofluorescent axons (Fig. 1A) were visualised in an Olympus fluorescence microscope fitted with a Chroma filter 31002. Full details of these methods have been published elsewhere (Tripovic et al. 2011).

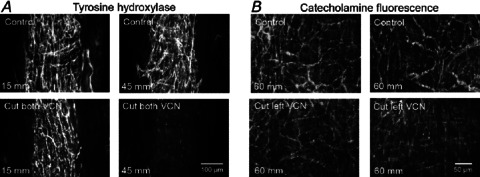

Figure 1. Density of noradrenergic axons on the rat tail artery was reduced 5–7 days after transection of one ventral collector nerve (VCN).

A, micrographs showing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-immunolabelled axons in longitudinal sections (20 μm thick) through the perivascular plexus of the tail artery at two levels along the tail of a control rat (above) and of a rat in which both VCNs had been transected 7 days previously (below). After cutting both VCNs, the plexus 10–20 mm along the tail was not affected but had disappeared at 40–50 mm along the tail. The 100 μm scale bar applies throughout. B, micrographs showing catecholamine fluorescence in whole mount preparations of FAGLU-treated tail arteries from ∼60 mm along the tail of two control rats (above) and two rats in which only the left VCN had been transected 5 days previously (below). After transecting one VCN, the configuration of the plexus remained similar to control but its brightness was reduced. With both techniques, each pair of vessels (above and below) was prepared and processed at the same time. The 50 μm scale bar applies throughout.

Catecholamine fluorescence

From rats in which one VCN had been transected 5–6 days previously, lengths of tail artery were dissected in physiological saline from 10–20, 40–50, 50–60 and 60–70 mm from the base of the tail. Segments from one control and one operated artery were pinned out together at in vivo length, opened longitudinally and pinned flat with the adventitial surface upwards. They were exposed to a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 (FAGLU) for 1 h, desiccated for 1.5 h and mounted in paraffin oil (Furness et al. 1977; Sittiracha et al. 1987). Catecholamine fluorescence in the whole perivascular plexus (Fig. 1B) was visualised using a Leica fluorescence microscope with UV excitation (Filter block A).

Data analysis

Artery segments from rats with one transected VCN are referred to as ‘partial denervation (PD) arteries’ and those from sham-operated rats or unoperated rats (used for assessing changes in electrophysiological responses) rats are referred to as ‘control arteries’.

The electrophysiological and myograph data were recorded using a PowerLab data acquisition system and the program Chart (ADInstruments, Bella Vista, NSW, Australia). Prior to statistical analysis, measurements of EJPs and NA-induced slow depolarisations in the each artery segment were averaged. In Fig. 2, the traces shown are the averages of responses for all artery segments of each group. The peak amplitude and decay time constant (τEJP) were assessed for the EJPs evoked by single stimuli whereas the peak amplitude of the NA-induced depolarisation evoked by five stimuli at 1 Hz was measured ∼15 s following first stimulus in the train. The τEJP was estimated by fitting a monoexponential function to the decay phase of the EJP using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA).

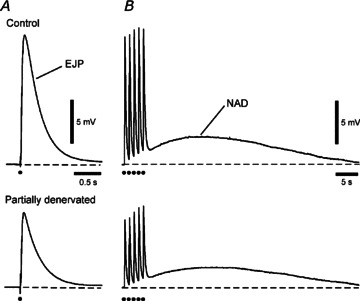

Figure 2. Amplitude of intracellularly recorded excitatory junction potentials (EJPs) was reduced in tail artery segments 60 mm along the tail at 5–7 days after partial denervation (PD).

Electrical responses evoked by (A) single supramaximal stimuli and (B) trains of five impulses at 1 Hz averaged for six control arteries (above) and six PD arteries (below). EJP amplitude was reduced by ∼50% in PD arteries. The slow noradrenaline-mediated depolarisation (NAD) evoked by trains of stimuli tended to be smaller in PD arteries but this was not significant.

For the myograph experiments, the peak amplitudes of the contractions to nerve stimulation and to PE, methoxamine, clonidine and 60 mm K+ were measured. The traces shown in the figures are the averages of contractions for all arteries in each group. EC50 values were estimated by fitting the data to the Hill equation using non-linear regression analysis (Prism 4, GraphPad software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). For the contractions evoked by 10 stimuli at 10 Hz, the rise time was determined between 10 and 90% of the peak contraction and the 50% decay time was determined from the 100–50% of the peak contraction. The 50% decay time of K+-evoked contractions was determined between the start of the relaxation following washout of the high [K+] solution to the point where the active force decayed to 50% of that measured at the start of relaxation.

All statistical comparisons were made using SPSS 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The electrophysiological data were compared using Student's t-tests. Comparisons between the concentration–contraction curves and the stimulus frequency–contraction curves were made using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a single independent variable (for comparisons between the groups). Other comparisons were made either with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey tests or Kruskal–Wallis tests follow by Mann–Whitney U-tests (with P values corrected using the Dunn–Sidak method) for pairwise comparisons if there was unequal variance between the groups of data (assessed using Levene's test of homogeneity of variance). The data compared using Mann–Whitney U-tests are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). All other data are presented as mean ± SEM. P values < 0.05 were considered as indicating a significant difference. In all cases, n indicates the number of animals studied.

Results

The perivascular plexus was uniformly less dense after PD

If both VCNs are transected, all FAGLU induced fluorescence (Sittiracha et al. 1987) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunofluorescence (Fig. 1A) disappears from ∼40 to 100 mm along the tail artery (see Introduction). The distribution of catecholamine-containing axon terminals was examined after 5 days when the distal part of the lesioned axons had degenerated (n= 3 control rats, 3 lesioned animals). Although individual distorted axons were present within the plexus of perivascular axons 50–70 mm along the tail of lesioned animals, the arrangement of nerve bundles in the adventitia was very similar to controls (Fig. 1B). However, the brightness of the fluorescence was markedly lower and, at high magnification, there were clearly fewer axons in each bundle. The important observation was that the transected axons disappeared from bundles throughout the plexus, i.e. they were evenly distributed and did not supply only one side or region of the artery.

Similar observations were made using TH immunohistochemistry in sections taken from above and below the region of artery used for mechanical studies, consistent with half the innervation at this level having degenerated.

EJP amplitude was halved after PD without changes in smooth muscle electrical properties

The amplitude of EJPs reflects the release of ATP at neurovascular junctions and is related to the density of innervation during development (Hill et al. 1985) and reinnervation (Jobling et al. 1992). Here the amplitude of EJPs evoked ∼60 mm along the tail artery by single supramaximal transmural stimuli was compared between 5–7 day lesioned rats (n= 6) and unoperated age-matched controls (n= 6). In accordance with the loss of half the noradrenergic axons, the amplitude of EJPs in PD arteries (8.6 ± 1.3 mV) was 54% of that in control arteries (16.0 ± 2.2 mV, unpaired t test P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). The NA-induced slow depolarisation (NAD) evoked by trains of five pulses at 1 Hz tended to be smaller in PD arteries (Fig. 2B), but this difference was not statistically significant (control 3.3 ± 0.3 mV, PD 2.4 ± 0.4 mV, unpaired t test P= 0.13).

Neither resting membrane potential (control −63 ± 1 mV, PD −64 ± 2 mV, unpaired t test P= 0.40) nor τEJP (control 274 ± 21 ms, PD 276 ± 20 ms, unpaired t test P= 0.76) differed between control and PD arteries.

Basal conditions for measurements of contraction were largely unaltered after PD

After arterial segments had been set up under tension for an equilibration period (see Methods), basal wall tension and lumen diameter did not differ significantly between PD and control arteries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basal mechanical properties of tail artery segments

| Lumen diameter (μm) | Wall tension (mN mm−1) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control, n= 7 | 823 ± 23 | 4.5 ± 0.1 |

| 1 Week PD, n= 7 | 786 ± 11 | 4.4 ± 0.1 |

| Control, n= 8 | 798 ± 13 | 4.3 ± 0.1 |

| 7 Weeks PD, n= 8 | 840 ± 14 | 4.6 ± 0.1 |

Data are presented as means ± SEMs. Control tissues were obtained from age-matched sham-operated rats. One-way analysis indicated no significant difference between groups in lumen diameters (P= 0.09) or wall tension (P= 0.21).

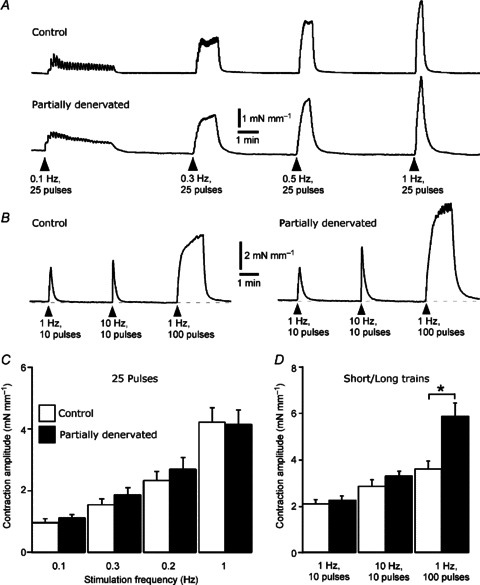

Nerve-evoked contractions were not reduced in amplitude 1 week after PD

Artery segments were stimulated with trains at low frequencies in the physiological range (see Jänig, 2006) and also with short HF trains (10 pulses at 10 Hz). In contrast to the amplitude of EJPs, the amplitude of the contraction to a single stimulus (measured from the response to the first stimulus in the train at 0.1 Hz) did not differ significantly from that in sham-operated controls (1 week: control 0.46 ± 0.09 mN mm−1, PD 0.57 ± 0.06 N mm−1, P= 0.20; 7 weeks: control 0.38 ± 0.06 mN mm−1, PD 0.46 ± 0.05 mN mm−1, P= 0.77). Although there was more temporal summation of individual contractions during repetitive stimulation at 0.1 and 0.3 Hz (Fig. 3A), there was no difference between peak increases in wall tension produced by the trains of 25 stimuli at these low frequencies (Fig. 3A and C; see Supplementary Fig. 1 for 7 week data) or by short trains at 1 and 10 Hz (Fig. 3B and D; see Supplementary Fig. 1 for 7 week data). Responses to 100 stimuli at 1 Hz, however, were nearly twice as large as controls after 1 week (Fig. 3B and D) although they did not differ from controls after 7 weeks (P= 0.51; see Supplementary Fig. 1 for 7 week data). After 3 days, when the majority of nerve terminals would have degenerated but the contribution of newly sprouted terminals could be ruled out, nerve-evoked contractions to single stimuli and to both short and long trains of stimuli did not differ significantly from those of control arteries, although contractions to 100 pulses at 1 Hz tended to be larger (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 3. Partial denervation (PD) of tail arteries for 1 week did not reduce the amplitude of contractions evoked by short and long trains of perivascular stimuli.

A, averaged traces showing increases in wall tension produced by 25 impulses at low frequencies (0.1, 0.3, 0.5 and 1 Hz) in segments from control (upper trace, n= 7) and 1 week PD (lower trace, n= 7) arteries. B, averaged traces showing increases in wall tension produced by 10 impulses at 1 and 10 Hz and 100 impulses at 1 Hz in segments from control (left, n= 7) and 1 week PD (right, n= 7) arteries. Note that the decay phase of the contractions was prolonged in PD arteries. C, peak increases in wall tension produced by 25 impulses at different frequencies, as in A. D, peak increases in wall tension produced by short and long trains of stimuli, as in B. Data for control (open bars, n= 7) and PD arteries (closed bars, n= 7) are presented as means and SEMs. Asterisks indicate significant differences between control and PD arteries (Tukey tests, *P < 0.05).

Nerve-evoked responses did not differ between 1- and 7-week PD arteries (between-groups comparison P= 0.82). Further, there were no significant differences in the amplitude of nerve-evoked contractions between artery segments from sham-operated and naïve age-matched rats (between-groups comparison: 1 week P= 0.48: 7 weeks P= 0.36), so that the similar amplitudes of nerve-evoked responses in PD and sham-operated arteries cannot be attributed to inadvertent nerve damage in the latter case.

Time course of nerve-evoked contractions was prolonged after PD

In 1-week PD arteries, the duration of the contractions to electrical stimulation was prolonged in comparison to controls (see Figs 3A and B, 4A and 5A; Table 2). This change was due primarily to slowing of the decay of the contractions as indicated by an increase in the 50% decay time, although the rise time was also slightly prolonged (Table 2). After 7 weeks, while the rise time in PD arteries was still significantly longer than control, the 50% decay time was not (Table 2).

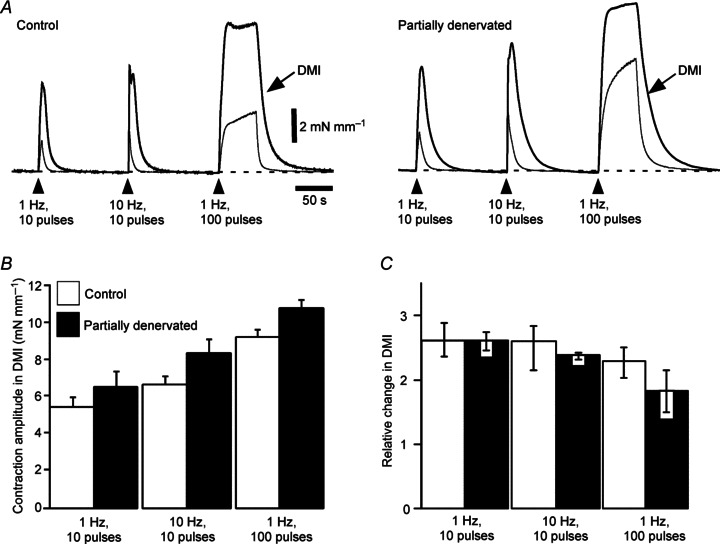

Figure 4. Partial denervation (PD) of tail arteries for 1 week did not significantly affect the enhancement of contraction amplitude by blocking neuronal re-uptake of noradrenaline.

A, overlaid averaged traces showing increases in wall tension produced by 10 impulses at 1 and 10 Hz and 100 impulses at 1 Hz in segments of control (left, n= 7) and PD (right, n= 7) arteries in the absence and in the presence of desmethylimipramine (DMI; 30 nm, thicker traces as indicated by arrows). Note that the decay phase of contractions was prolonged after PD, both in the absence and in the presence of DMI. B, peak increases in wall tension evoked by these trains of stimuli in the presence of DMI. C, relative change in peak amplitude of contractions produced by DMI (ratio of amplitude in DMI to amplitude in control solution). Data for control (open bars, n= 7) and PD arteries (closed bars, n= 7) are presented as (B) means and SEMs or (C) medians and interquartile ranges. In PD arteries, contractions tended to be larger than control in the presence of DMI and the facilitatory effect of DMI on contractions to the long trains at 1 Hz to be reduced, but these effects were not significant.

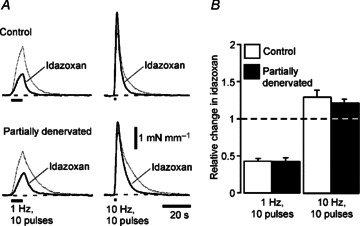

Figure 5. Partial denervation (PD) of tail arteries for 1 week did not change the facilitatory effect of idazoxan (0.1 μm) on the amplitude of contractions to short high-frequency trains, but increased the acceleration of their decay produced by idazoxan.

A, averaged traces showing contractions evoked by 10 impulses at 1 Hz (left) and 10 Hz (right) in control (above, n= 7) and PD (below, n= 7) arteries before (thin traces) and during (thicker traces) exposure to idazoxan (0.1 μm). B, relative changes in amplitude of contractions to 10 impulses at 1 and 10 Hz produced by idazoxan in control (open bars, n= 7) and 1 week PD arteries (closed bars, n= 7). Data are presented as means and SEMs. The dashed line indicates no change in contraction amplitude. Contractions to 1 Hz in both control and 1 week PD arteries were reduced in amplitude by idazoxan whereas those to 10 Hz were increased. Both responses were abbreviated in idazoxan.

Table 2.

Effect of partial denervation (PD) on time course of contractions evoked by brief trains

| Rise time (s) | 50% Decay time (s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| –DMI | +DMI | –DMI | +DMI | |

| Control | 1.4 | 2.2 | 4.4 | 14.5 |

| n= 7 | (1.4–1.5) | (1.9–2.2) | (4.0–4.8) | (12.4–16.6) |

| 1 Week PD | 1.8† | 5.3 | 7.8† | 20.0* |

| n= 7 | (1.5–1.8) | (3.3–6.5) | (5.8–10.9) | (19.2–23.4) |

| Control | 1.5 | 2.1 | 4.3 | 17.3 |

| n= 8 | (1.3–1.5) | (2.0–2.2) | (3.9–4.7) | (14.6–18.1) |

| 7 Weeks PD | 1.6* | 3.1* | 5.9 | 15.4 |

| n= 8 | (1.5–1.8) | (2.5–3.6) | (5.3–6.6) | (15.1–18.6) |

Data are for contractions to 10 stimuli at 10 Hz and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (in parentheses) in the absence and in the presence of desmethylimipramine (DMI). Control tissues were obtained from age-matched sham-operated rats. Significant differences between control and PD arteries are indicated by *P < 0.05 and †P < 0.01 (Mann–Whitney U-tests).

DMI enhancement of nerve-evoked contractions was little changed after PD

In both control and PD arteries, blockade of NATs with DMI (30 nm) increased the amplitude of contractions to trains of 10 stimuli at 1 and 10 Hz and of 100 stimuli at 1 Hz (Fig. 4A). In the presence of DMI, the peak amplitude of contractions evoked by all patterns of stimulation tended to be larger in PD arteries than in control arteries (Fig. 4A and B; see Supplementary Fig. 1C for 7 week data). However, the relative enhancement of contractions induced by DMI was similar in PD and control arteries (Fig. 4C), being significantly smaller only for the response to 100 pulses at 1 Hz 7 weeks after PD (see Supplementary Fig. 1).

Blockade of NATs also prolonged the duration of nerve-evoked contractions to short HF trains of stimuli in all groups of arteries (Fig. 4A, Table 2). In the presence of DMI, the 50% decay time 1 week after PD was still significantly longer than control (Table 2), and the relative change in 50% decay time produced by DMI was similar in PD (2.7 ± 0.3) and control (3.3 ± 0.4, P= 0.58) arteries. Therefore, the prolonged decay of nerve-evoked contractions in arteries 1 week after PD is unlikely to be due only to reduced clearance of released NA.

After 7 weeks, the 50% decay time in the absence and in the presence of DMI did not differ between PD and control arteries (Table 2) but the proportional change in 50% decay time produced by DMI was significantly less in PD arteries (2.8 ± 0.2) than in control arteries (4.0 ± 0.4, P < 0.05). These proportional changes did not significantly differ between 1 and 7 weeks in PD (P= 0.99) or control (P= 0.36) arteries.

Involvement of prejunctional α2-adrenoceptors in nerve-evoked contractions was not changed after PD

In both control and PD arteries, idazozan (0.1 μm) increased the peak amplitude of contractions to short HF trains by ∼30% at both 1 and 7 weeks after the lesion (Fig. 5A and B; see Supplemental Fig. 2 for 7 week data). In contrast, the amplitude of contractions to 10 pulses at 1 Hz was reduced by ∼60% in both groups of arteries (Fig. 5A and B).

Abbreviation of nerve-evoked contractions by idazoxan was enhanced after PD

Idazoxan accelerated the decay of contractions to short trains at 1 and 10 Hz in both control and PD arteries (see Fig. 5A), confirming that a slow component of contraction results from activation of postjunctional α2-adrenoceptors (Bao et al. 1993). For 10 Hz trains, the prolongation of the 50% decay time in PD arteries after 1 week (see ‘–DMI’ in Table 2) was abolished in the presence of idazoxan (control 2.6 ± 0.4 s, PD 3.6 ± 0.3 s, P= 0.53). Accordingly, the reduction in the 50% decay time produced by idazoxan at 1 week after PD was greater than in controls (ratio of 50% decay time with/without idazoxan; control 0.68 ± 0.05, PD 0.53 ± 0.06, P < 0.05). Furthermore, while the 50% decay time both in the absence (see Table 2) and in the presence of idazoxan (control 2.9 ± 0.3 s, PD 3.1 ± 0.6 s, P= 0.72) did not differ between 7 week PD arteries and their controls, the reduction in the 50% decay time produced by idazoxan was also greater at this time point in PD arteries (ratio of 50% decay time with/without idazoxan; control 0.71 ± 0.04, PD 0.55 ± 0.03, P < 0.01).

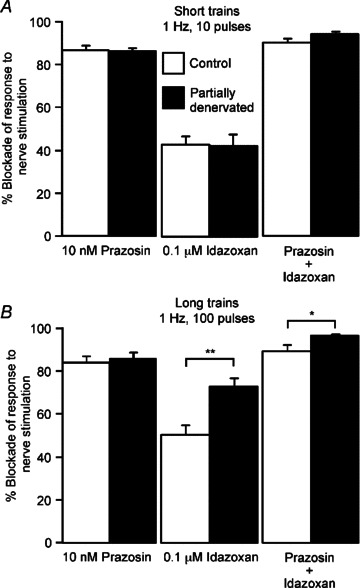

Blockade of nerve-evoked contractions by idazoxan was enhanced after PD

The degree of blockade of contractions to both 10 and 100 pulses at 1 Hz produced by prazosin did not differ significantly between PD arteries and their controls (Fig. 6A and B; P > 0.3 for all comparisons; see Supplementary Fig. 2 for 7 week data).

Figure 6. Blockade of contractions evoked by prolonged trains at 1 Hz by the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist idazoxan was enhanced 1 week after partial denervation (PD) of tail arteries, but blockade by the α1-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin was not affected.

Percentage blockade of contractions evoked by (A) 10 and (B) 100 impulses at 1 Hz produced by prazosin (10 nm), idazoxan (0.1 μm) or both agents in control (open bars, n= 7) and PD arteries (closed bars, n= 7). Data are presented as means and SEMs. Asterisks indicate significant differences between control and PD arteries (Tukey tests: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

The blockade produced by idazoxan in 1 week PD arteries did not differ from control for contractions to 10 pulses at 1 Hz (Figs 5A and 6A), but it produced significantly greater blockade during longer trains (Fig. 6B). In addition, the enhancement of contractions to 100 pulses at 1 Hz after PD (Fig. 3B and D) was abolished by idazoxan (control 1.69 ± 0.41 mN mm−1, PD 1.71 ± 0.38 mN mm−1, P= 0.99). Idazoxan's blockade of contractions to both short and long trains at 1 Hz tended to be larger after 7 weeks although this was not statistically significant (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for 7 week data).

Blockade of nerve-evoked contractions by the combination of prazosin and idazoxan was in all cases ≥90% (Fig. 6, see Supplementary Fig. 2 for 7 week data).

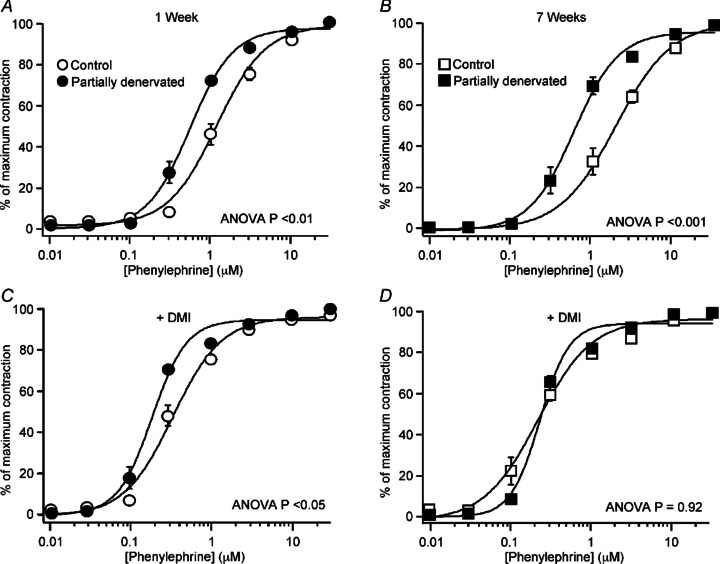

Reactivity to exogenous α1-adrenoceptor agonists increased transiently, but that to the α2-adrenoceptor agonist clonidine increased over time after PD

Phenylephrine

In the absence of DMI, the PE concentration–response curves for 1 and 7 week PD arteries were shifted to the left relative to controls (Fig. 7A and B) with a significant reduction in EC50 values (Table 3). In addition, contractions of PD arteries to the maximum concentration of PE tested (30 μm) were greater than control in both 1 and 7 week PD arteries (Table 3). It should be noted that this increase in sensitivity to PE was not reflected in a greater blockade of nerve-evoked responses by prazosin (Fig. 6), so that this change in reactivity to PE does not appear to involve the α1-adrenoceptors accessed by NA released from the nerves.

Figure 7. Sensitivity of the tail artery to the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine was transiently increased after partial denervation (PD).

Data for control and PD arteries (A, C) after 1 week (n= 7 for both groups) and (B, D) 7 weeks (n= 8 for both groups) are presented as percentage of the maximum contraction to PE. A and B, in the absence of DMI, PE concentration–response curves for PD arteries lay to the left of those for control arteries. C and D, in the presence of desmethylimipramine (DMI, 30 nm), all concentration–response curves were shifted to the left. In DMI, the curve for 1 week PD arteries still lay to the left of that for control arteries but the curve for the two groups of 7 week arteries were overlaid. Data are presented as means and SEMs (some SEM bars are smaller than the symbols). P values indicate significant differences between the curves (ANOVA between-group comparisons).

Table 3.

Effects of partial denervation (PD) on concentration– response curves for phenylephrine in the absence and presence of desmethylimipramine (DMI)

| Phenylephrine | Phenylephrine + DMI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (μm) | Maximum contraction (mN mm−1) | EC50 (μm) | Maximum contraction (mN mm−1) | |

| Control | 1.19 | 10.5 ± 0.4 | 0.33 | 11.4 ± 0.6 |

| n= 7 | (1.03–1.53) | (0.28–0.41) | ||

| 1 Week PD | 0.62† | 13.7 ± 0.7† | 0.20† | 13.2 ± 0.6 |

| n= 7 | (0.58–0.65) | (0.18–0.21) | ||

| Control | 2.03 | 12.5 ± 0.7 | 0.20 | 11.4 ± 0.5 |

| n= 8 | (1.32–2.57) | (0.14–0.28) | ||

| 7 Weeks PD | 0.62† | 15.1 ± 0.4* | 0.21 | 14.8 ± 0.4† |

| n= 8 | (0.47–0.64) | (0.20–0.27) | ||

Data are presented as means ± SEMs or medians and interquartile ranges (in parentheses). Control tissues were obtained from age-matched sham-operated rats. Significant differences between control and PD arteries are indicated by *P < 0.05 and †P < 0.01 (Student's unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U-test as appropriate).

DMI (30 nm) shifted the PE concentration–response curves to the left and reduced the EC50 values in all groups of arteries (Fig. 7C and D; Table 3; P < 0.01 for all comparisons). The increase in PE sensitivity produced by DMI (measured as the ratio of EC50 values in the absence/presence of DMI) tended to be smaller in PD arteries than in controls and this change was significant after 7 weeks (1 week: control 3.9, IQR 2.9–4.3; PD 3.1, IQR 2.9–3.4, P= 0.48; 7 weeks: control 9.4, IQR 5.9–12.9; PD 2.3, IQR 1.8–2.7; P < 0.01). Whereas these ratios did not change significantly over time after PD (P= 0.67), the EC50 ratios in control arteries were significantly greater after 7 weeks than 1 week (P < 0.05). This suggests that uptake into the perivascular plexus normally increases with age and that this did not occur after PD.

In the presence of DMI, the EC50 for PE in 1 week PD arteries was smaller than in controls, whereas after 7 weeks the EC50 values were similar (Table 3), indicating that the raised sensitivity of the vascular muscle to PE was transient and that, after 7 weeks, hypersensitivity to this α1-adrenoceptor agonist could be attributed to reduced neuronal uptake. Only in 7 week PD arteries was the maximum contraction to PE in the presence of DMI significantly greater than in controls (Table 3).

Methoxamine

The EC50 for methoxamine, which is not a substrate for NAT (Trendelenburg et al. 1970), decreased slightly 1 week following PD but this did not reach the level of significance (Table 4). PD produced no change in the maximum contraction to methoxamine at either time point.

Table 4.

Effects of partial denervation (PD) on concentration– response curves for methoxamine and clonidine

| Methoxamine | Clonidine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (μm) | Maximum contraction (mN mm−1) | EC50 (μm) | Maximum contraction (mN mm−1) | |

| Control | 1.02 ± 0.13 | 11.9 | 0.075 | 8.8 ± 0.5 |

| n= 7 | (11.1–12.5) | (0.061–0.078) | ||

| 1 Week PD | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 12.8 | 0.038 | 10.6 ± 0.2† |

| n= 7 | (11.9–13.4) | (0.029–0.067) | ||

| Control | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 13.1 | 0.055 | 10.4 ± 0.5 |

| n= 8 | (12.2–14.6) | (0.027–0.064) | ||

| 7 Weeks PD | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 13.1 | 0.024* | 11.2 ± 0.5 |

| n= 8 | (12.5–13.3) | (0.021- 0.26) | ||

Data are presented as means ± SEMs or medians and interquartile ranges (in parentheses). Control tissues were obtained from age-matched sham-operated rats. Significant differences between control and PD arteries are indicated by *P < 0.05 and †P < 0.01 (Student's unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U-test as appropriate).

Clonidine

The EC50 for clonidine did not differ between 1 week PD arteries and their controls but the maximum contraction to clonidine was increased by ∼20% in PD arteries (Table 4). In 7 week PD arteries, there was no significant difference in maximum contraction but the EC50 for clonidine was reduced compared to that of their controls (Table 4).

K+-evoked contractions were not affected in amplitude or duration after PD

In both 1 and 7 week PD arteries, the peak amplitude of contractions to depolarisation of the vascular muscle with 60 mm K+ did not differ significantly from that of controls (1 week: control 9.5 ± 0.22 mN mm−1, PD 8.3 ± 0.2 mN mm−1, P= 0.22; 7 weeks: control 10.7 ± 0.3 mN mm−1, PD 11.5 ± 0.5 mN mm−1, P= 0.50). Similarly, the 50% decay time of the K+-evoked contractions was not significantly affected (1 week: control 11.1± 0.5 s, PD 9.5 ± 0.7 s, P= 0.34; 7 weeks: control 12.9 ± 0.7 s, PD 13.1 ± 0.7 s, P= 0.98).

Discussion

The key finding of this study is that, after removing half of the innervating axons, contractions of tail arteries evoked by supramaximal stimulation of the perivascular terminals were not smaller in amplitude than those from sham-operated rats. This applied not only for the contractions evoked by various trains of stimuli, but also for the response to a single stimulus, when prolongation of the time course of contraction cannot contribute to an increase in its amplitude. However, the prolongation of nerve-evoked contractions 1 week after PD (due to an increased α2-adrenoceptor-mediated component of contraction) and the consequent increase in temporal summation during trains of stimuli appears to explain why the peak contractions to long trains of stimuli were larger than control. This amplification did not occur 7 weeks after PD when the decay of contraction was no longer prolonged. Because blockade of α2-adrenoceptors did not make the contractions of PD arteries smaller than those of control arteries, other mechanisms must maintain their amplitude. The maintained size of the contractions was also not explained by reductions in either α2-adrenoceptor-mediated autoinhibition or neuronal re-uptake of released NA. Together, the magnitude of the observed mechanistic changes is inadequate to explain why contraction amplitude is not reduced. Furthermore, as only minor differences in neurovascular transmission were observed between 3–7 days and 7 weeks after the lesion, plasticity of the surviving axons could not account for additional contractile force in response to supramaximal stimuli. For these reasons, the findings appear to imply that nerve-evoked contractions are maximal when only a subset of the perivascular axons release NA. Thus, our hypothesis that supramaximal nerve-evoked contractions depend on activation of all of the innervating axons is disproved, at least for the tail artery.

Unchanged prejunctional mechanisms

The surgical intervention ensured that half the innervation was removed and could not regenerate (Sittiracha et al. 1987; Tripovic et al. 2010) and the histochemistry was consistent with this. Furthermore, the reduced EJP amplitudes confirmed that the amount of ATP released from the remaining axons was half that of controls, so that it seems very likely that the amount of NA released was similarly reduced. However, while there was a tendency for the NAD to be smaller in PD arteries this change was not statistically significant. It should be noted that the NAD measured at its peak (∼15 s following the first stimulus in the train) is primarily due to α2-adrenoceptor-mediated closure of KATP channels (Tan et al. 2007) and that this is limited to 3–5 mV when all KATP channels are blocked, so that the amplitude of the NAD is not linearly related to the amount of NA released. Furthermore, the amplitude of the NAD may also have been affected by the enhanced responsiveness of the vascular muscle to α2-adrenoceptor activation. In reinnervated arteries, which became hyperresponsive to clonidine (Tripovic et al. 2011), the amplitude of the NAD tended to be larger than control despite a sparse perivascular plexus (Jobling et al. 1992).

In completely denervated tail arteries, the primary mechanism that explains the increased reactivity of these vessels to catecholamines is the loss of NATs (Tripovic et al. 2010). If NATs are located on all axon terminals, and NA is cleared as it diffuses away from its release sites, the decay of NA concentration after each stimulus would be expected to be slower when the innervation density is less. In reinnervated arteries with a similar paucity of nerve terminals (Tripovic et al. 2011), the enhancement of amplitude and duration of nerve-evoked contractions by blockade of NATs with DMI was less than in controls, consistent with the loss of NATs. However, PD produced little change in the relative enhancement of contractions produced by DMI, so that reduced clearance of NA does not explain why the peak amplitude of nerve-evoked contractions in PD arteries was at least as big as in controls. Rather, it appears that, in normal sympathetic terminals, it is NATs located on the varicosities that participate in NA release that are primarily involved in its clearance.

Whereas activation of prejunctional α2-adrenoceptors with clonidine reduces both ATP and NA release in the rat tail artery, autoinhibition by endogenously released NA selectively reduces release of NA but not that of ATP (Brock & Tan, 2004). Thus, reduced autoinhibition after PD should increase NA but not ATP release. However, the effectiveness of autoinhibition after PD was not modified, despite the probable halving of the number of prejunctional α2-adrenoceptors, because idazoxan produced a similar relative increase in the amplitude of α1-adrenoceptor-mediated contractions to short HF trains of stimuli as in controls.

A change in the release mechanism that increased the amount of NA released per innervating axon could have contributed to the size of the contractions after PD. While we did not test this directly, because techniques such as in situ amperometry do not allow comparisons between preparations, such a change would require a feedback mechanism to signal to the remaining axons that their target artery is receiving reduced amounts of transmitter. As indicated above, the possibility that this feedback is due to reduced autoinhibition of NA release has been excluded. An alternative possibility is the accumulation of neurotrophic factors leading to sprouting of the remaining axons. Neurotrophins, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) secreted by the smooth muscle (Korsching & Thoenen, 1985), or by invading immune cells following axon degeneration (Peleshok & Ribeiro-da-Silva, 2012), might accumulate when half the innervating axons disappear. However, sympathetic terminals on adult mammalian arteries do not undergo collateral growth in response to increased levels of target-derived NGF (Elliott et al. 2009). Furthermore, reinnervation of the partially denervated circle of Willis in rats by sprouting of the contralateral sympathetic innervation occurred over several weeks, while its branches failed to be reinnervated after 4 months (Handa et al. 1991). Because nerve-evoked contractions were as large as control 3 days after PD, even in response to a single stimulus, an increase in NA release or in the number of neurovascular junctions seems unlikely to be involved.

Relatively small alterations in postjunctional mechanisms

The electrical properties of the smooth muscle, the lumen diameter of the arterial segments and the contractions evoked by depolarisation with 60 mm K+ were all unaffected by PD. The lack of change in passive electrical properties of the vascular muscle means that changes in sensitivity to nerve stimulation and to agonists were not related to non-specific changes in excitability. Furthermore, the finding that PD did not change the contractile response of the vascular muscle to direct depolarisation suggests that voltage-dependent Ca2+ entry and/or the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile elements were not affected. These findings also suggest that the larger maximal contractions to PE (with or without DMI; Table 3) do not reflect a non-specific increase in muscle responsiveness.

After PD, a small transient increase in sensitivity of the vascular muscle to PE was detected in the presence of DMI 1 week after PD, which was much less than that in the first 2 weeks following complete denervation of the tail artery (Tripovic et al. 2010). After 7 weeks, the denervated artery was hyperreactive only to α1-adrenoceptor agonists that are substrates for NATs, as seen at the same time after PD. Despite these changes in reactivity to exogenously applied agonists between 1 and 7 weeks after PD, the blockade of nerve-evoked contractions by prazosin was not affected at either time point. This implies that the characteristics of the α1-adrenoceptors accessed by nerve-released NA were not changed.

In the tail artery, nerve-evoked contractions are also mediated by α2-adrenoceptors on the vascular smooth muscle, apparently acting in synergy with the junctional α1-adrenoceptors (Yeoh et al. 2004a,b). There was a small increase in postjunctional reactivity to the α2-adrenoceptor agonist clonidine, shown by a greater maximum contraction after 1 week and a reduced EC50 after 7 weeks. However, more importantly, the degree of blockade of nerve-evoked contractions by idazoxan was greater than control 1 week after PD. This greater contribution of postjunctional α2-adrenoceptors to contractions in PD arteries is most readily explained by increased summation due to prolongation of the slow α2-adenoceptor-mediated component of contraction, as idazoxan also abbreviated the decay of nerve-evoked contractions. This implies that a greater contribution of postjunctional α2-adrenoceptor activation is more important than any reduction in clearance of NA for the prolongation of nerve-evoked contractions in PD arteries. However, this effect is not large enough to explain the maintenance of contraction amplitude although it clearly contributed to the enhanced responses to long trains of stimuli.

Finally, as the combined blockade of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors reduced nerve-evoked contractions by >90% in both PD and control arteries, a greater contribution of co-transmitters (such as ATP) to neurovascular transmission does not seem to contribute to the effectiveness of the residual innervation in PD arteries.

Comparison with reinnervation

Notably, the amplitudes of nerve-evoked contractions after PD and after reinnervation (Tripovic et al. 2011) were similar to or larger than control in the presence of only half the normal innervation. There are several factors to consider:

A reduction in the innervation did not affect the contractile properties of vascular muscle because the force developed by both PD and reinnervated arteries to 60 mm K+ was similar to that of normally innervated arteries.

In PD arteries, the normal size of nerve-evoked contractions could not be attributed to a reduction in either autoinhibition of NA release or the activity of NATs. In contrast, after reinnervation, part of the recovery of contraction amplitude could be explained by deficits in these mechanisms (Tripovic et al. 2011). This difference may be explained by the relative immaturity of the newly regenerated axon terminals in the re-established perivascular plexus.

In both conditions, the percentage blockade of nerve-evoked contractions produced by prazosin was similar to that in control arteries, implying no difference in the effect of activating junctionally located α1-adrenoceptors despite fewer innervating axons.

In PD arteries, the percentage blockade produced by idazoxan was initially enhanced during long trains of stimuli when summation of the prolonged contractions potentiated the peak amplitude. However, in the reinnervated arteries and in the longer term PD arteries, blockade by idazoxan became similar to control despite maintained hyperreactivity of the vascular muscle to clonidine.

The maintained effectiveness of the junctional α1- and α2-adrenoceptors in activating contraction when the innervation was halved might suggest that their density is raised and/or there are a greater number of junctions made by the innervating axons after these interventions. If either was the explanation, it would imply remarkable matching between contractile responses under three distinct innervation conditions (control, partial denervation and reinnervation).

Mechanisms of neurovascular transmission – new insights?

We hypothesised that supramaximal nerve-evoked contractions of the partially innervated tail artery would depend on activation of all of its innervation. The finding that contractile responses were not halved when the innervation was halved suggests that normally ∼50% of the sympathetic innervation can evoke the maximal contractile response to nerve stimulation. The possibility that there is substantial redundancy of the innervation of the tail artery could theoretically be tested directly by stimulating one VCN to an isolated arterial segment, although making such a preparation without damage to the nerve supply would be extremely difficult.

Removal of half the innervating sympathetic axons to the rat pineal gland (Zigmond et al. 1981, 1985) only transiently reduced the nocturnal elevation of serotonin N-acetyltransferase activity (an enzyme involved in the synthesis of melatonin). In contrast, after silencing half the intact postganglionic innervation (by transecting the preganglionic trunk on one side), enzyme activity remained reduced. Thus, restoration of neural control occurred only when half the sympathetic axons had degenerated, leading to the suggestion that the effectiveness of NA released by the surviving axons was greater due to loss of NATs. However, a reduction in NA uptake does not explain the maintained amplitude of nerve-evoked evoked contractions in PD tail arteries, because the facilitatory effect of blocking NAT on these responses was similar to control (see above). Furthermore, in the pineal gland, recovery of function after unilateral denervation occurred prior to the onset of sprouting and was unchanged after 2 weeks during which sprouting restored the terminal density to ∼80% of normal (Lingappa & Zigmond, 1987). Thus, an explanation for maintained function at the early stages after partial denervation is still required.

It is difficult to envisage how reducing the number of innervating axons would not reduce the number of activated α-adrenoceptors. An alternative possibility is that the postreceptor mechanisms activated by the α-adrenoceptors are ‘saturated’ when only 50% of the innervation is activated. While α-adrenoceptors are distributed throughout the vascular wall (Methven et al. 2009a), only those located at the adventitial–medial border (and possibly only those at neuromuscular junctions) are likely to be activated by NA released by single or short trains of stimuli. Consistent with this, contractions evoked by trains of stimuli are less than half the amplitude of the maximum contractions evoked by exogenously applied α-adrenoceptor agonists, which can access receptors throughout the vascular wall.

Nerve-released NA triggers contraction by initiating asynchronous Ca2+ waves in individual muscle cells at the adventitial–medial border (Iino et al. 1994; Wier et al. 2009). These Ca2+ waves are generated by repetitive cycles of Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, followed by a period of Ca2+ reuptake during which the cells are refractory to activation (Lee et al. 2005). When release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum is blocked by ryanodine, the early phase of contractions evoked in the rat tail artery by trains of stimuli at 2 Hz is strongly inhibited (Sulpizio & Hieble, 1991). This suggests that asynchronous activation of the innervated muscle cells leads to coordinated contraction of the muscle syncytium. As PD did not change the distribution of axon bundles in the perivascular nerve plexus, and the frequency of junctions on individual cells is not known either normally or after PD, the numbers of muscle cells that are directly influenced by nerve-released NA may not be greatly changed by activating only half the innervation. Furthermore, as only a small proportion of varicosities release neurotransmitter in response to each electrical stimulus (Brock & Cunnane, 1993), the maximum nerve-evoked contraction may not require much NA at all. We cannot exclude the possibility that the mechanisms that couple junctionally located adrenoceptors to the contractile mechanism are selectively augmented. However, testing this idea is dependent on monitoring the cellular processes activated via junctional adrenoceptors, and will require further technological advances.

Summary

Overall, the similarities between the nerve-evoked responses of control and PD arteries were remarkable, even when only single stimuli were applied. The results of these experiments indicate that the failure of contraction amplitude to be reduced by halving the number of innervating axons is not readily explained by changes in the contractile properties of the vascular muscle, prejunctional autoinhibition of NA release, NAT activity or junctional adrenoceptor sensitivity. Although it is possible that NA release from the remaining axons may be potentiated, and changes in postjunctional pathways may lead to greater activation of the contractile elements, these adjustments would require feedback mechanisms that have not yet been envisaged. It seems simpler to conclude that the postreceptor mechanisms activated by nerve-released NA are normally saturated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Svetlana Pianova for assistance with histochemistry. This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia under a Project Grant (350903) and a Fellowship Grant to J.B. (350904).

Glossary

- DMI

desmethylimipramine

- EJP

excitatory junction potential

- HF

high frequency

- IQR

interquartile range

- NA

noradrenaline

- NAD

noradrenaline-induced depolarisation

- NAT

noradrenaline transporter

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- PD

partial denervation

- PE

phenylephrine

- τEJP

time constant of decay of excitatory junction potential

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

- VCN

ventral collector nerve

Author's present address

J. Brock: Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Vic. 2010, Australia.

Author contributions

J.B. and E.M. contributed to the conception and design of the experiments. All three authors contributed to the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supporting Information

References

- Al Dera H, Habgood MD, Furness JB, Brock JA. Prominent contribution of L-type Ca2+ channels to cutaneous neurovascular transmission that is revealed after spinal cord injury augments vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H752–762. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00745.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres KH, von During M, Janig W, Schmidt RF. Degeneration patterns of postganglionic fibers following sympathectomy. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1985;172:133–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00319596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao JX, Gonon F, Stjärne L. Frequency- and train length-dependent variation in the roles of postjunctional α1- and α2-adrenoceptors for the field stimulation-induced neurogenic contraction of rat tail artery. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993;347:601–616. doi: 10.1007/BF00166943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C. Transmission from vasoconstrictor and vasodilator nerves to single smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig uterine artery. J Physiol. 1969;205:695–708. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E, Law A, Bell D, Johnson CD. Effects of varying impulse number on cotransmitter contributions to sympathetic vasoconstriction in rat tail artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H2007–2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01061.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock JA, Cunnane TC. Neurotransmitter release mechanisms at the sympathetic neuroeffector junction. Exp Physiol. 1993;78:591–614. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1993.sp003709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock JA, Tan JH. Selective modulation of noradrenaline release by α2-adrenoceptor blockade in the rat-tail artery in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:267–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock JA, Yeoh M, McLachlan EM. Enhanced neurally evoked responses and inhibition of norepinephrine reuptake in rat mesenteric arteries after spinal transection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H398–405. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00712.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassell JF, McLachlan EM, Sittiracha T. The effect of temperature on neuromuscular transmission in the main caudal artery of the rat. J Physiol. 1988;397:31–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cragg BG. Failure of conduction and of synaptic transmission in degenerating mammalian C fibres. J Physiol. 1965;179:95–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly CJ, Ross RA, Whyte J, Henstridge CM, Irving AJ, McGrath JC. Fluorescent ligand binding reveals heterogeneous distribution of adrenoceptors and ‘cannabinoid-like’ receptors in small arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:787–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty JR. Subtypes of functional α1-adrenoceptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:405–417. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0174-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer G. The role of neuronal and extraneuronal plasma membrane transporters in the inactivation of peripheral catecholamines. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;91:35–62. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckles SP, Adner M, Edvinsson L, Krause DN. Neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor blockade does not alter adrenergic nerve responses of the rat tail artery. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;340:75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J, MacLellan A, Saini JK, Chan J, Scott S, Kawaja MD. Transgenic mice expressing nerve growth factor in smooth muscle cells. Neuroreport. 2009;20:223–227. doi: 10.1097/wnr.0b013e32831add70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness JB, Costa M, Blessing WW. Simultaneous fixation and production of catecholamine fluorescence in central nervous tissue by perfusion with aldehydes. Histochem J. 1977;9:745–750. doi: 10.1007/BF01003068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes S, Moura D. Vascular adrenoceptors: an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:319–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MA, Dutton JL, Balcar VJ, Barden JA, Bennett MR. P2X (purinergic) receptor distributions in rat blood vessels. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1999;75:147–155. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(98)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa Y, Nojyo Y, Hayashi M. Patterns of reinnervation of denervated cerebral arteries by sympathetic nerve fibers after unilateral ganglionectomy in rats. Exp Brain Res. 1991;86:82–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00231042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Hirst GD, Ngu MC, van Helden DF. Sympathetic postganglionic reinnervation of mesenteric arteries and enteric neurones of the ileum of the rat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1985;14:317–334. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(85)90079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst GD. Neuromuscular transmission in arterioles of guinea-pig submucosa. J Physiol. 1977;273:263–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino M, Kasai H, Yamazawa T. Visualization of neural control of intracellular Ca2+ concentration in single vascular smooth muscle cells in situ. EMBO J. 1994;13:5026–5031. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänig W. The Integrative Action of the Autonomic Nervous System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen BC, Swigart PM, Simpson PC. Ten commercial antibodies for α1-adrenergic receptor subtypes are nonspecific. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;379:409–412. doi: 10.1007/s00210-008-0368-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling P, McLachlan EM, Janig W, Anderson CR. Electrophysiological responses in the rat tail artery during reinnervation following lesions of the sympathetic supply. J Physiol. 1992;454:107–128. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsching S, Thoenen H. Treatment with 6-hydroxydopamine and colchicine decreases nerve growth factor levels in sympathetic ganglia and increases them in the corresponding target tissues. J Neurosci. 1985;5:1058–1061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-04-01058.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa JR, Zigmond RE. A histochemical study of the adrenergic innervation of the rat pineal gland: evidence for overlap of the innervation from the two superior cervical ganglia and for sprouting following unilateral denervation. Neuroscience. 1987;21:893–902. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Kuo KH, Dai J, van Breemen C. Asynchronous calcium waves in smooth muscle cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:733–741. doi: 10.1139/y05-083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Duckles SP. Acute effects of nicotine on rat mesenteric vasculature and tail artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;264:1305–1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luff SE, Young SB, McLachlan EM. Proportions and structure of contacting and non-contacting varicosities in the perivascular plexus of the rat tail artery. J Comp Neurol. 1995;361:699–709. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Mackenzie JF, Daly CJ. Pharmacological implications of cellular localization of α1-adrenoceptors in native smooth muscle cells. J Auton Pharmacol. 1999;19:303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2680.1999.tb00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methven L, McBride M, Wallace GA, McGrath JC. The α1B/D-adrenoceptor knockout mouse permits isolation of the vascular α1A-adrenoceptor and elucidates its relationship to the other subtypes. Br J Pharmacol. 2009a;158:209–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methven L, Simpson PC, McGrath JC. Alpha1A/B-knockout mice explain the native α1D-adrenoceptor's role in vasoconstriction and show that its location is independent of the other α1-subtypes. Br J Pharmacol. 2009b;158:1663–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvany MJ, Halpern W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circ Res. 1977;41:19–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleshok JC, Ribeiro-da-Silva A. Neurotrophic factor changes in the rat thick skin following chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve. Mol Pain. 2012;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummery NM, Tripovic D, Mclachlan EM, Brock JA. Sympathetic vasoconstriction is potentiated in arteries caudal but not rostral to a spinal cord transection in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2010;11:2077–2089. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittiracha T, McLachlan EM, Bell C. The innervation of the caudal artery of the rat. Neuroscience. 1987;21:647–659. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulpizio A, Hieble JP. Lack of a pharmacological distinction between α1 adrenoceptors mediating intracellular calcium-dependent and independent contractions to sympathetic nerve stimulation in the perfused rat caudal artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;257:1045–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JH, Al Abed A, Brock JA. Inhibition of KATP channels in the rat tail artery by neurally released noradrenaline acting on postjunctional α2-adrenoceptors. J Physiol. 2007;581:757–765. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend SA, Jung AS, Hoe YS, Lefkowitz RY, Khan SA, Lemmon CA, Harrison RW, Lee K, Barouch LA, Cotecchia S, Shoukas AA, Nyhan D, Hare JM, Berkowitz DE. Critical role for the α1B adrenergic receptor at the sympathetic neuroeffector junction. Hypertension. 2004;44:776–782. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000145405.01113.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg U, Maxwell RA, Pluchino S. Methoxamine as a tool to assess the importance of intraneuronal uptake of l-norepinephrine in the cat's nictitating membrane. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970;172:91–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripovic D, Pianova S, McLachlan EM, Brock JA. Transient supersensitivity to α-adrenoceptor agonists, and distinct hyper-reactivity to vasopressin and angiotensin II after denervation of rat tail artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:142–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripovic D, Pianova S, McLachlan EM, Brock JA. Slow and incomplete sympathetic reinnervation of rat tail artery restores the amplitude of nerve-evoked contractions provided a perivascular plexus is present. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H541–554. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00834.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wier WG, Zang WJ, Lamont C, Raina H. Sympathetic neurogenic Ca2+ signalling in rat arteries: ATP, noradrenaline and neuropeptide Y. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:31–37. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XP, Chiba S. Existence of different α1-adrenoceptor subtypes in junctional and extrajunctional neurovascular regions in canine splenic arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1852–1858. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh M, McLachlan EM, Brock JA. Chronic decentralization potentiates neurovascular transmission in the isolated rat tail artery, mimicking the effects of spinal transection. J Physiol. 2004a;561:583–596. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.074948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh M, McLachlan EM, Brock JA. Tail arteries from chronically spinalized rats have potentiated responses to nerve stimulation in vitro. J Physiol. 2004b;556:545–555. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.056424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharia J, Hillier C, MacDonald A. α1-Adrenoceptor subtypes involved in vasoconstrictor responses to exogenous and neurally released noradrenaline in rat femoral resistance arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:915–924. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]