Abstract

Introduction

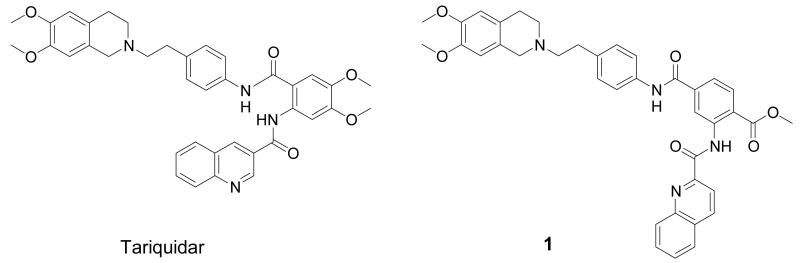

The multidrug efflux transporter breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) is highly expressed in the blood-brain barrier (BBB), where it limits brain entry of a broad range of endogenous and exogenous substrates. Methyl 4-((4-(2-(6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-2-yl)ethyl)phenyl)amino-carbonyl)-2-(quinoline-2-carbonylamino)benzoate (1) is a recently discovered BCRP-selective inhibitor, which is structurally derived from the potent P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitor tariquidar. The aim of this study was to develop a new PET tracer based on 1 to map BCRP expression levels in vivo.

Methods

1 was labelled with 11C in its methyl ester function by reaction of the corresponding carboxylic acid 2 with [11C]methyl triflate. PET imaging of [11C]-1 was performed in wild-type, Mdr1a/b(−/−), Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice (n=3 per mouse type) and radiotracer metabolism was assessed in plasma and brain.

Results

Brain-to-plasma ratios of unchanged [11C]-1 were 4.8- and 10.3-fold higher in Mdr1a/b(−/−) and in Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice, respectively, as compared to wild-type animals, but only modestly increased in Bcrp1(−/−) mice. [11C]-1 was rapidly metabolized in vivo giving rise to a polar radiometabolite which was taken up into brain tissue.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that [11C]-1 preferably interacts with P-gp rather than BCRP at the murine BBB which questions its reported in vitro BCRP selectivity. Consequently, [11C]-1 appears to be unsuitable as a PET tracer to map cerebral BCRP expression.

Keywords: breast cancer resistance protein, P-glycoprotein, blood-brain barrier, PET, inhibitor, tariquidar

1. Introduction

The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP, ABCG2) can actively efflux a broad range of endogenous and exogenous substrates across biological membranes [1]. BCRP limits oral bioavailability and mediates renal and hepatobiliary excretion of its substrates, and thereby influences the pharmacokinetics of several drugs. In addition, BCRP can confer multidrug resistance to tumor cells. Recent work, relying mainly on the use of transporter knockout mice, has revealed important contributions of BCRP to the blood-brain, blood-testis and blood-fetal barriers [1, 2].

In the blood-brain barrier (BBB), BCRP co-localizes with P-glycoprotein (P-gp, ABCB1) at the luminal side of endothelial cells of brain capillaries. Interestingly, whereas expression of P-gp is higher than that of BCRP in the murine BBB [3], the opposite seems to be true in humans. Recent data show that mRNA levels of BCRP are about eightfold higher than P-gp mRNA levels in human brain capillaries [4]. However, as BCRP has a substantial overlap in substrate specificity with P-gp [5], the functional role of BCRP at the BBB has remained elusive, despite the availability of BCRP-deficient mice [2].

A powerful strategy to studying function and expression of ABC transporters in vivo is positron emission tomography (PET) together with radiolabelled transporter substrates or inhibitors [6]. We and others have successfully applied this concept to imaging cerebral P-gp by using radiolabelled P-gp substrates, such as (R)-[11C]verapamil [7, 8] or [11C]-N-desmethyl-loperamide [9], and P-gp inhibitors, such as [11C]laniquidar [10], [11C]elacridar [11] or [11C]tariquidar [12]. For translating this promising concept to the visualization of BCRP, the availability of PET probes with high selectivity for BCRP over P-gp is crucial. However, because of the recent discovery of the BCRP transporter, only a few selective BCRP inhibitors have been reported so far. Fumitremorgin C, a diketopiperazine, isolated from Aspergillus fumigatus, was reported first, but cannot be used in vivo due to its neurotoxicity [13]. The most potent BCRP inhibitor known to date is the fumitremorgin C analogue Ko143 [14]. The potent third-generation P-gp inhibitor tariquidar (Fig. 1) [15] has been shown to also inhibit BCRP, but at higher concentrations than those at which it inhibits P-gp [16]. It has recently been discovered that structural modifications at the benzamide core of tariquidar result in potent and selective BCRP inhibitors [17]. Out of a series of 10 tariquidar-like compounds, methyl 4-((4-(2-(6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-2-yl)ethyl)phenyl)amino-carbonyl)-2-(quinoline-2-carbonylamino)benzoate (1, Fig. 1) was identified as a potent BCRP inhibitor, which inhibits BCRP-mediated transport of mitoxantrone in topotecan-resistant MCF-7 breast cancer cells with a half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 60 nM and displays approximately 500-fold selectivity for inhibition of BCRP over P-gp [17].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of tariquidar and 1.

The aim of this work was the development of a new PET tracer based on 1 to study BCRP expression levels in vivo. Here, we report on the precursor synthesis and 11C-labelling of 1. Moreover, a first small-animal PET evaluation of [11C]-1 was performed in wild-type and transporter knockout mice to assess the interaction of [11C]-1 with BCRP and P-gp at the BBB.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. General

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Schnelldorf, Germany), Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) and Apollo Scientific Ltd (Bredbury, UK) at analytical grade and used without further purification. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Advance DPx200 (200 and 50 MHz). Chemical shifts are reported in δ units (ppm) relative to the Me4Si line as internal standard (s, d, t, m, Cq for singlet, doublet, triplet, multiplet and quaternary carbon, respectively) and J values are reported in Hertz. Elemental analysis was performed on a Perkin Elmer 2400 CHN Elemental Analyzer. [11C]CH4 was produced via the 14N(p,α)11C nuclear reaction by irradiating nitrogen gas containing 10% hydrogen using a PETtrace cyclotron equipped with a CH4 target system (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). [11C]CH3I was prepared via the gas-phase method [18] in a TRACERlab FXC Pro synthesis module (GE Healthcare) and converted into [11C]methyl triflate by passage through a column containing silver-triflate impregnated graphitized carbon [19].

2.2. Animals

Female FVB (wild-type), Mdr1a/b(−/−), Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) (triple knockout) mice weighing 25-30 g were purchased from Taconic Inc. (Germantown, USA). The study was approved by the local Animal Welfare Committee and all study procedures were performed in accordance with the Austrian Animal Experiments Act.

2.3. Sodium 4-((4-(2-(6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-2-yl)ethyl)phenyl)amino-carbonyl)-2-(quinoline-2-carbonylamino)benzoate (2)

To a suspension of 1 [17] (78 mg, 0.12 mmol) in H2O (15 mL) and MeOH (20 mL), solid NaOH (180 mg, 4.5 mmol) was added and the reaction mixture stirred at 70°C for 12 h. Then the MeOH was evaporated and the remaining solution was cooled at 3°C for 14 h. The precipitate was filtered off and washed with ice-cold water to obtain the title compound (77 mg, 98% theoretical yield). 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.60-2.91 (m, 8H), δ 3.56 (s, 2H, CH2), δ 3.71 (s, 6H, 2×OCH3), δ 6.60-6.72 (m, 2H), δ 7.19-7.32 (m, 2H), δ 7.54-7.64 (m, 1H), 7.67-7.81 (m, 3H), δ 7.84-7.97 (m, 1H), δ 8.04-8.35 (m, 4H), δ 8.55-8.67 (m, 1H), δ 9.28-9.37 (m, 1H), δ 10.28 (s, 1H), δ 15.53 (s, 1H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 28.4 (CH2), δ 32.5 (CH2), δ 50.6 (CH2), δ 55.1 (CH2), δ 55.4 (OCH3), δ 55.5 (OCH3), δ 59.7 (CH2), δ 109.9 (CH), δ 111.7 (CH), δ 118.5 (CH), δ 118.9 (CH), δ 120.3 (2×CH), δ 120.8 (CH), δ 125.9 (Cq), δ 126.7 (Cq), δ 128.0 (Cq), δ 128.2 (Cq), δ 128.8 (2×CH), δ 129.1 (Cq), δ 129.7 (CH), δ 130.3 (CH), δ 131.1 (CH), δ 135.7 (Cq), δ 136.5 (Cq), δ 137.2 (Cq), δ 137.8 (CH), δ 139.9 (Cq), δ 146.2 (Cq), δ 146.9 (Cq), δ 147.1 (Cq), δ 151.0 (Cq), δ 163.2 (Cq), δ 165.8 (Cq), δ 169.1 (Cq). Elemental analysis calculated for C37H33N4NaO6·3H2O: C, 62.88; H, 5.56; N, 7.93%. Found: C, 63.14; H, 5.32; N, 7.79%.

2.4. [11C]Methyl 4-((4-(2-(6,7-dimethoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-2-yl)ethyl)phenyl)amino-carbonyl)-2-(quinoline-2-carbonylamino)benzoate ([11C]-1)

Using a TracerLab FXC Pro synthesis module, [11C]methyl triflate was bubbled through a solution of 2 (0.5 mg, 0.78 μmol) in acetone (0.5 mL) containing aq. NaOH (0.3 M, 5 μL, 1.5 μmol, 1.9 eq.). After heating for 4 min at 60°C, the reaction mixture was cooled (25°C), diluted with H2O (0.5 mL) and injected into a built-in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. A Chromolith Performance RP 18-e (100-4.6 mm) column (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was eluted with CH3CN/MeOH/NH4OAc buffer (0.2 M, pH 5.0) (350/75/575, v/v/v) at a flow rate of 4 mL/min. The HPLC eluate was monitored in series for radioactivity and ultraviolet (UV) absorption at a wavelength of 227 nm. On this system, radiolabelling precursor 2 and product [11C]-1 eluted with retention times of 0.5-1.5 min and 4-5 min, respectively. The product fraction was diluted with H2O (100 mL) and passed over a C18 Sep-Pak Plus cartridge (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA), which had been pre-activated with EtOH (5 mL) and H2O (10 mL). The cartridge was then washed with H2O (10 mL) followed by elution of [11C]-1 with EtOH (3 mL). EtOH was then removed by heating at 100°C under a stream of argon and the product formulated in a mixture of 0.9% aq. saline/ethanol/polyethylene glycol 300 (50/15/35, v/v/v) at an approximate concentration of 370 MBq/mL for i.v. injection into animals. Radiochemical purity and specific activity of [11C]-1 were determined by analytical radio-HPLC using a Chromolith Performance RP 18-e (100-4.6 mm) column eluted with CH3CN/MeOH/NH4OAc buffer (0.2 M, pH 5.0) (385/85/530, v/v/v) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. UV detection was performed at a wavelength of 227 nm. The retention time of [11C]-1 was about 13-14 min on this HPLC system.

2.5. Small-animal PET imaging and PET data analysis

Wild-type, Mdr1a/b(−/−), Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice (n=3 per mouse type) underwent PET scans with [11C]-1. Prior to each PET experiment, mice were placed in an induction box and anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane. When unconscious, animals were taken from the box, kept under anesthesia with 1.5-2% isoflurane administered via a mask and warmed throughout the whole experiment at around 38°C. After positioning animals in the PET imaging chamber, [11C]-1 (28±16 MBq in a volume of about 0.1 mL) was administered via a lateral tail vein as an i.v. bolus over approximately 30 s. At the start of radiotracer injection, a dynamic PET scan of 60 min duration was initiated using a microPET Focus220 scanner (Siemens, Medical Solutions, Knoxville, USA). During each scanning session, two mice were examined simultaneously.

PET images were reconstructed by Fourier rebinning followed by 2-dimensional filtered back projection with a ramp filter. The standard data correction protocol (normalization, attenuation, decay correction and injection decay correction) was applied to the data. The whole brain was manually outlined on multiple planes of the PET summation images using the image analysis software Amide [20], and time-activity curves (TACs), expressed in units of percent injected dose per gram tissue (%ID/g), were calculated. Area under the curve from time zero to the last observation point (AUC, h·%ID/g) of individual brain TACs was calculated using the Kinetica™ 2000 version 3.0 software package (InnaPhase Corporation, Philadelphia, USA). The %ID/g values measured with PET in brain tissue of individual animals at 25 min after radiotracer injection were divided by the %ID/g values in whole blood determined in 4 separate mice (n=1 per mouse type, see below) to obtain brain-to-blood ratios of radioactivity.

2.6. Metabolite analysis

A separate group of animals (n=1 per mouse type), which did not undergo PET scanning, was injected under isoflurane-anesthesia with [11C]-1 (133±44 MBq) for metabolite analysis. At 25 min after radiotracer injection, a terminal blood sample (approximately 1 mL) was collected by cardiac puncture into an heparinized tube and centrifuged to obtain plasma (3,000×g, 5 min, 21°C). In addition, whole brains were removed. Aliquots of blood and plasma were weighted and counted for radioactivity in a 1-detector Wallac gamma counter (Perkin Elmer Instruments, Wellesley, USA), which had been cross-calibrated with the PET camera. Radioactivity counts were corrected for radioactive decay and expressed as %ID/g.

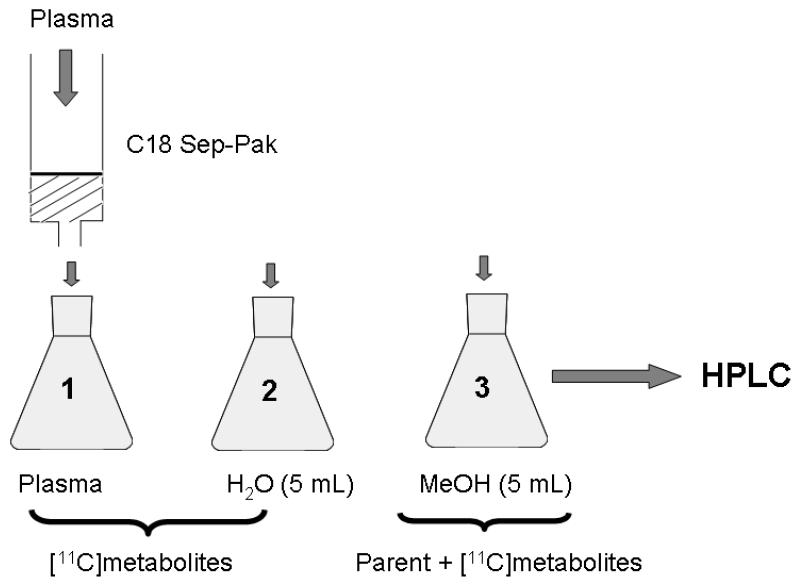

Radiometabolites of [11C]-1 in mouse plasma were determined using a solid-phase extraction (SPE) assay (Fig. 2), which was slightly modified from a previously published procedure [21]. Plasma samples were diluted with H2O (0.5 mL), spiked with unlabelled 1 (13 μg in 10 μL of DMSO), acidified with 5M aq. HCl (40 μL) and loaded on a Sep-Pak vac tC18 cartridge (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA), which had been pre-activated with MeOH (3 mL) and H2O (5 mL). The cartridge was first washed with H2O (5 mL) and then eluted with MeOH (5 mL). Radioactivity in all 3 fractions (plasma, H2O, MeOH) was measured in a 1-detector Wallac gamma counter. The percentage of total radioactivity that remained on the SPE cartridge after elution was <1%. Fractions 2 and 3 were further analyzed by HPLC using 2 different systems. In system A, a Chromolith Performance RP 18-e (100-4.6 mm) column was eluted at 35°C with CH3CN/MeOH/NH4OAc buffer (0.2 M, pH 5.0) (328/72/600, v/v/v) at a flow rate of 3 mL/min (injected volume: 200 μL). In system B, an Aminex HPX-87H column (300 mm × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) was eluted at 44°C with 1 mM aq. H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min (injected volume: 100 μL). For both HPLC systems, UV detection was performed at 227 nm. On system A, an unidentified polar radiometabolite of [11C]-1 and unchanged [11C]-1 eluted with retention times of 1-2 min and 8-10 min, respectively. On system B, the polar radiometabolite of [11C]-1 eluted with a retention time of 18-19 min, whereas unchanged [11C]-1 remained on the column. For validation of the SPE assay, [11C]-1 dissolved in H2O (0.5 mL) was subjected to the SPE procedure showing that all radioactivity was quantitatively recovered in the MeOH fraction.

Fig. 2.

Scheme of SPE/HPLC protocol used for analysis of radiometabolites of [11C]-1 in mouse plasma.

Mouse brain was washed twice with ice-cold H2O and homogenized in 0.8 mL of aq. saline solution (0.9%, w/v) using an IKA T10 basic Ultra-turrax (IKA Laboratory Equipment, Staufen, Germany). The brain homogenate was mixed with CH3CN (1.5 mL) and centrifuged (3 min, 4°C, 13,000×g). The supernatant was injected into HPLC systems A and B.

2.7. Stability testing

[11C]-1 formulated for i.v. injection was kept for 2 h at room temperature and analyzed by HPLC system A. Moreover, mouse plasma (0.5 mL, in Na citrate, LAMPIRE Biological Laboratories, Inc., Pipersville, PA, USA) was mixed with formulated [11C]-1 solution (20 μL, approximately 40 MBq) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a gently shaking water bath. Mouse plasma was then processed by the SPE procedure followed by HPLC analysis of individual fractions.

2.8. Statistical analysis

For all outcome parameters, differences between groups were tested using the Mann-Whitney U test. The level of statistical significance was set to p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Chemical and radiochemical synthesis

Compound 1 was prepared as described in the literature [17]. Methyl ester hydrolysis of 1 afforded the corresponding free acid 2, which was used as radiolabelling precursor of [11C]-1. Compound 2 was reacted with [11C]methyl triflate in acetone containing aq. NaOH to give [11C]-1 ready for i.v. injection in a decay-corrected radiochemical yield of 5.4±2.4% (n=11), based on [11C]CH4, in a total synthesis time of approximately 35 min. Radiochemical purity of [11C]-1 was greater than 98% and specific activity at the end of synthesis was 284±254 GBq/μmol (n=6). The identity of [11C]-1 was confirmed by HPLC co-injection with unlabelled 1.

3.2. Small-animal PET

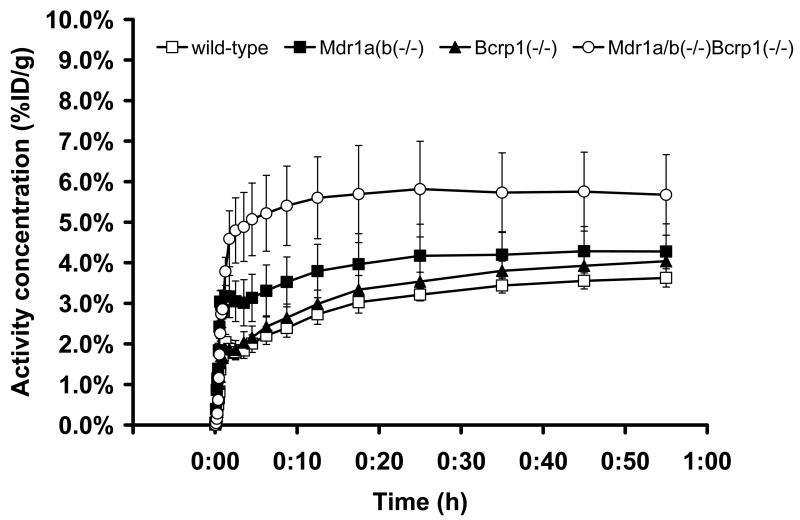

[11C]-1 was evaluated in PET scans in wild-type, Mdr1a/b(−/−), Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice. In Fig. 3, brain TACs obtained after injection of [11C]-1 into the 4 investigated mouse types are shown. In table 1, pharmacokinetic parameters of [11C]-1 in mouse brain and blood are given. AUC values of brain TACs were 1.3- and 1.8-fold higher in Mdr1a/b(−/−) mice (p=0.0495) and in triple knockout mice (p=0.0495), respectively, as compared to wild-type animals, but no significant increases were seen in Bcrp1(−/−) mice (p=0.127) (table 1). Brain radioactivity uptake measured with PET at 25 min after tracer injection was normalized to blood radioactivity levels determined in a separate group of animals (table 1). In triple knockout mice, brain-to-blood ratios of radioactivity were significantly higher compared to wild-type animals (p=0.0495), whereas no significant differences to wild-type animals were found for Mdr1a/b(−/−) and Bcrp1(−/−) mice.

Fig. 3.

Whole-brain TACs (mean %ID/g±SD, n=3 per mouse type) obtained after injection of [11C]-1 into wild-type (open squares), Mdr1a/b(−/−) (filled squares), Bcrp1(−/−) (filled triangles) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) (open circles) mice.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of [11C]-1$ in brain and blood of wild-type, Mdr1a/b(−/−), Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−) Bcrp1(−/−) mice.

| Wild-type | Mdr1a/b(−/−) | Bcrp1(−/−) | Mdr1a/b(−/−) Bcrp1(−/−) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain AUC (h·%ID/g)* | 2.8±0.2 | 3.6±0.6† | 3.1±0.2 | 5.1±0.9† |

| Brain concentration, 25 min (%ID/g)* |

3.2±0.2 | 4.2±0.8 | 3.5±0.2 | 5.8±1.2† |

| Blood concentration, 25 min (%ID/g)** |

2.1 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 1.8 |

| Brain-blood ratio, 25 min | 1.5±0.1 | 1.7±0.3 | 1.6±0.1 | 3.2±0.6† |

| Brain-plasma ratio of unchanged [11C]-1, 25 min |

1.8±0.1 | 8.6±1.6† | 2.1±0.1† | 18.3±3.7† |

Except for brain-plasma ratio of unchanged [11C]-1, all values were calculated using total radioactivity (i.e. parent plus radiometabolites) in blood and brain. Values are given as mean±SD.

n=3 per mouse type

n=1 per mouse type

A statistically significant difference was observed compared to wild-type mice (Mann-Whitney U test, p<0.05).

3.3. Metabolite analysis

In a separate group of mice (n=1 per mouse type), blood was collected at 25 min after injection of [11C]-1. Total radioactivity concentrations in blood appeared to be similar in all 4 mouse types (table 1). Mouse plasma was analyzed for radiometabolites of [11C]-1 using an SPE/HPLC assay as outlined in Fig. 2. Radioactivity in SPE fractions 1 and 2 was found to represent polar radiometabolites of [11C]-1, whereas unchanged [11C]-1 was recovered in fraction 3 (MeOH). At 25 min after injection of [11C]-1, 75%, 72%, 81% and 82% of total radioactivity was recovered in fractions 1 and 2, and 25%, 28%, 19% and 18% in fraction 3 of wild-type, Mdr1a/b(−/−), Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice, respectively. Further analysis of fraction 3 using HPLC system A revealed that approximately one half of total radioactivity was in the form of unchanged [11C]-1 and the other half in the form of an unidentified polar radiometabolite. The percentages of unchanged [11C]-1 in mouse plasma at 25 min after tracer injection were 13%, 17%, 14% and 11% for wild-type, Mdr1a/b(−/−), Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice, respectively.

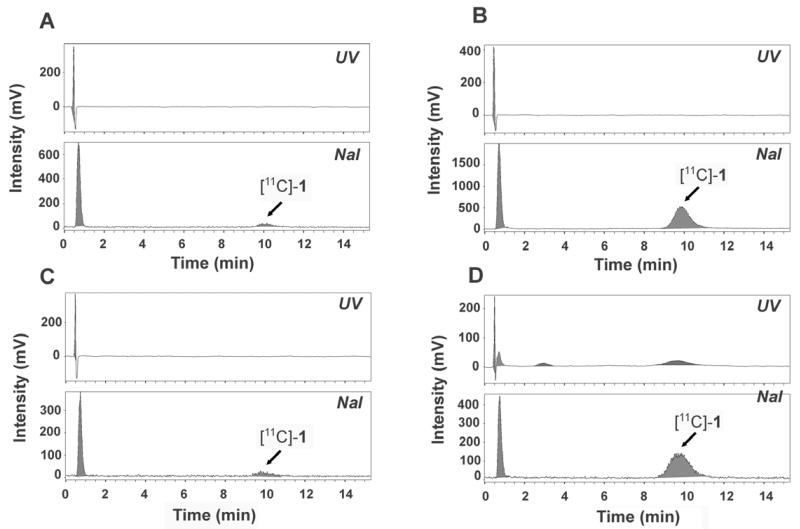

Mouse brain, which was collected at 25 min after injection of [11C]-1, was also analyzed for radiometabolites of [11C]-1 using HPLC system A. In Fig. 4, the HPLC chromatograms of brain tissue extracts of all 4 mouse types are shown. In wild-type and Bcrp1(−/−) mice 12% and 25% of total radioactivity, respectively, was in the form of unchanged [11C]-1. In Mdr1a/b(−/−) and triple knockout mice the percentages of unchanged [11C]-1 were 62% and 69%, respectively. The remainder of brain radioactivity represented the polar radiometabolite of [11C]-1 (Fig. 4). After multiplying total radioactivity in brain and plasma at 25 min after tracer injection by the fractions of unchanged [11C]-1, mean brain-to-plasma ratios were 4.8-, 1.2- and 10.3-fold higher in Mdr1a/b(−/−), Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice (p=0.0495), respectively, compared to wild-type animals (table 1).

Fig. 4.

Radio-HPLC chromatograms of brain tissue extracts obtained at 25 min after injection of [11C]-1 into wild-type (A), Mdr1a/b(−/−) (B), Bcrp1(−/−) (C) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) (D) mice. In the upper channel UV absorption (wavelength: 227 nm) is measured, and in the lower channel radioactivity. For HPLC conditions (system A) see Material and methods section.

3.4. Stability testing

[11C]-1 was found to be 100% stable for at least 2 h when kept in formulation solution for i.v. injection. However, [11C]-1 was not stable in mouse plasma. SPE/HPLC analysis showed that >98% of total radioactivity had degraded to an unidentified polar radiolabelled species after incubation of [11C]-1 in mouse plasma at 37°C for 30 min. The degradation product eluted on both HPLC systems with comparable retention times as the polar radiometabolite of [11C]-1 found in vivo in plasma and brain tissue extracts.

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis and radiosynthesis

As 1 contains three OCH3 groups (Fig. 1), the most straightforward 11C-labelling approach appeared to be O-11C-methylation of O-desmethyl-1, which offers the advantage that the radiotracer retains the chemical structure of native 1. Our recent experience with the synthesis of radiolabelling precursors for [11C]elacridar and [11C]tariquidar, which both share the dimethoxy-tetrahydroisoquinoline moiety with 1 (Fig. 1), has shown that it was not feasible to synthesize derivatives with a free phenolic OH function in this part of the molecule [11]. Therefore, the only possible site for 11C-methylation of 1 remained the methyl carboxylic ester moiety. We first synthesized 1 as described in the literature [17], whereby we could take advantage of our previous experience with and the availability of synthetic intermediates from the synthesis of tariquidar [12]. The radiolabelling precursor 2 was obtained in almost quantitative yield by hydrolysis of the methyl ester group in 1 with NaOH. Reaction of 2 with [11C]methyl triflate provided [11C]-1 in a decay-corrected radiochemical yield (based on [11C]CH4) of 5.4±2.4%. The semipreparative HPLC purification of crude [11C]-1 showed that 30-50% of total radioactivity was in the form of a polar radiolabelled by-product, which presumably represented [11C]CH3OH due to a possible competing reaction of [11C]methyl triflate with NaOH. However, as the radiochemical yield of [11C]-1 was largely sufficient for performing PET experiments in mice and as the specific activity of [11C]-1 was acceptable, no attempts were made to further increase the radiochemical yield of [11C]-1.

4.2. Small-animal PET and metabolite studies

[11C]-1 was evaluated in vivo by performing PET experiments in wild-type mice, in Mdr1a/b(−/−) mice, and in Bcrp1(−/−) and Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice, which do not express the putative pharmacologic target of [11C]-1 (Fig. 3). We have previously used this experimental set-up for characterizing the radiolabelled P-gp inhibitors [11C]elacridar and [11C]tariquidar [11, 12, 22]. This approach is well suited to elucidate the individual contributions of P-gp and BCRP in the BBB to limiting brain entry of ABC transporter ligands. Our present data show that brain-blood ratios of total radioactivity following injection of [11C]-1 were significantly higher in triple knockout mice, whereas no significant differences as compared to wild-type mice were found in single knockout mice (table 1). The employed approach is not suitable to discern a radiolabelled transporter substrate from a non-transported inhibitor as the effect of transporter knockout will be the same for both types of compounds. In transporter-competent mice, radiolabelled substrate is hindered from entering brain parenchyma by transporter-mediated efflux. Similarly, non-transported inhibitor, when administered at a tracer dose, will be kept out of the brain by high-affinity binding to transporters at the BBB. Transporter knockout, on the other hand, will increase brain radioactivity uptake of both radiolabelled substrates and non-transported inhibitors as the gatekeeper function of the transporter(s) is abolished. It is not known, at present, if 1 inhibits BCRP by acting as a competitive substrate or as an inhibitor. However, given its structural similarity with tariquidar, which is a non-transported inhibitor, it seems likely that 1 behaves similarly.

When looking at the PET results obtained in transporter knockout mice (Fig. 3, table 1) one gains the impression that the contribution of BCRP is smaller than that of P-gp to limiting brain entry of [11C]-1, which questions the excellent BCRP over P-gp selectivity of 1 observed in in vitro transport assays [17]. This assumption is further supported by data from HPLC analysis of brain tissue extracts (Fig. 4), which showed that the percentage of unchanged [11C]-1 was higher in brains of mice lacking P-gp (Mdr1a/b(−/−) and triple knockout mice) as compared to mice which only lacked BCRP (Bcrp1(−/−)). Accordingly, brain-to-plasma ratios of unchanged [11C]-1 were several-fold higher in Mdr1a/b(−/−) and triple knockout mice and only modestly increased in Bcrp1(−/−) mice, as compared to wild-type animals (table 1). An interesting finding of this study was that the combined effect of P-gp and BCRP knockout (Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice) on brain uptake of [11C]-1 was far greater than the sum of its individual contributions in Mdr1a/b(−/−) and Bcrp1(−/−) mice. This observation has also been made by other investigators for other P-gp/BCRP substrate drugs [23, 24] and points to a concerted action of P-gp and BCRP in the BBB. In the absence of BCRP, P-gp may take over its role in limiting brain entry of dual substrates or inhibitors and vice versa.

HPLC analysis of mouse plasma extracts obtained at 25 min after injection of [11C]-1 showed that [11C]-1 was metabolically unstable as only 11-17% of total radioactivity was in the form of unchanged parent. This is somewhat surprising given the close structural similarity of 1 with tariquidar, which we found to be hardly metabolized in vivo in rats, at least during the time course of a 1 h PET scan [12]. We found that [11C]-1 was also unstable when incubated in vitro in mouse plasma and presumably degraded to the same polar radiolabelled compound as observed in the in vivo samples. We first suspected that the polar radiometabolite of [11C]-1 represented a one-carbon species, such as [11C]formaldehyde or [11C]formic acid, resulting from cleavage of the [11C]methyl ester moiety in [11C]-1, given that this route of metabolism is common for radiotracers bearing radiolabelled methyl ester functions [25, 26]. However, analysis on HPLC system B, which is well suited for the analysis of polar compounds, showed that the polar radiometabolite of [11C]-1 was not identical with formaldehyde or formic acid. Therefore it seems reasonable to assume that metabolism of [11C]-1 occurred elsewhere in the molecule, presumably at sites which were structurally distinct from tariquidar (e.g. the substituted benzamide moiety). Importantly, the polar radiometabolite of [11C]-1 appeared to penetrate the BBB as indicated by HPLC analysis of brain tissue extracts (Fig. 4). This is also in line with the observation that the brain TACs following injection of [11C]-1 were slowly rising during the time course of the PET experiment (Fig. 3). Brain uptake of the polar radiometabolite, which was presumably independent of ABC transporter expression, appeared to blunt the overall differences in total brain radioactivity uptake seen between wild-type and transporter knockout animals (table 1).

5. Conclusion

The putative BCRP-selective inhibitor 1 was labelled with 11C and characterized in vivo by performing PET experiments in wild-type and transporter knockout mice. Our in vivo data indicate that [11C]-1 preferably interacts with P-gp in the BBB, which questions the in vitro BCRP selectivity reported for 1 and emphasizes the importance of performing in vivo experiments as early as possible in the rational design of PET ligands for ABC transporters. [11C]-1 was rapidly metabolized in vivo giving rise to an unidentified radiometabolite which was taken up into brain tissue. Consequently, [11C]-1 seems to be unsuitable to map the distribution of BCRP at the BBB. PET imaging of transporter knockout mice as employed in the present study is a well suited study paradigm to gain a first impression of the in vivo transporter selectivity of novel ABC transporter ligands.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) project “Transmembrane Transporters in Health and Disease” (SFB F35) and from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement number 201380 (“Euripides”). The authors thank Gloria Stundner (AIT) and Thomas Filip and Maria Zsebedics (Seibersdorf Laboratories GmbH) for their skilful help with laboratory animal handling and the staff of the radiochemistry laboratory (Seibersdorf Laboratories GmbH) for continuous support.

Footnotes

Thomas Erker and Oliver Langer contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Vlaming ML, Lagas JS, Schinkel AH. Physiological and pharmacological roles of ABCG2 (BCRP): recent findings in Abcg2 knockout mice. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61(1):14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagas JS, Vlaming ML, Schinkel AH. Pharmacokinetic assessment of multiple ATP-binding cassette transporters: the power of combination knockout mice. Mol Interv. 2009;9(3):136–45. doi: 10.1124/mi.9.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamiie J, Ohtsuki S, Iwase R, Ohmine K, Katsukura Y, Yanai K, et al. Quantitative atlas of membrane transporter proteins: development and application of a highly sensitive simultaneous LC/MS/MS method combined with novel in-silico peptide selection criteria. Pharm Res. 2008;25(6):1469–83. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dauchy S, Dutheil F, Weaver RJ, Chassoux F, Daumas-Duport C, Couraud PO, et al. ABC transporters, cytochromes P450 and their main transcription factors: expression at the human blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem. 2008;107(6):1518–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsson P, Pedersen JM, Norinder U, Bergstrom CA, Artursson P. Identification of novel specific and general inhibitors of the three major human ATP-binding cassette transporters P-gp, BCRP and MRP2 among registered drugs. Pharm Res. 2009;26(8):1816–31. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-9896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannan P, John C, Zoghbi SS, Halldin C, Gottesman MM, Innis RB, et al. Imaging the function of P-glycoprotein with radiotracers: pharmacokinetics and in vivo applications. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86(4):368–77. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bankstahl JP, Kuntner C, Abrahim A, Karch R, Stanek J, Wanek T, et al. Tariquidar-induced P-glycoprotein inhibition at the rat blood-brain barrier studied with (R)-11C-verapamil and PET. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(8):1328–35. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.051235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner CC, Bauer M, Karch R, Feurstein T, Kopp S, Chiba P, et al. A pilot study to assess the efficacy of tariquidar to inhibit P-glycoprotein at the human blood-brain barrier with (R)-11C-verapamil and PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(12):1954–61. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.063289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liow JS, Kreisl W, Zoghbi SS, Lazarova N, Seneca N, Gladding RL, et al. P-Glycoprotein Function at the Blood-Brain Barrier Imaged Using 11C-N-Desmethyl-Loperamide in Monkeys. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(1):108–15. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luurtsema G, Schuit RC, Klok RP, Verbeek J, Leysen JE, Lammertsma AA, et al. Evaluation of [11C]laniquidar as a tracer of P-glycoprotein: radiosynthesis and biodistribution in rats. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36(6):643–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dörner B, Kuntner C, Bankstahl JP, Bankstahl M, Stanek J, Wanek T, et al. Synthesis and small-animal positron emission tomography evaluation of [11C]-elacridar as a radiotracer to assess the distribution of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier. J Med Chem. 2009;52(19):6073–82. doi: 10.1021/jm900940f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer F, Mairinger S, Dörner B, Kuntner C, Stundner G, Bankstahl JP, et al. Synthesis and μPET evaluation of the radiolabelled P-glycoprotein inhibitor [11C]tariquidar [symposium abstract] Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(Suppl 2):S222. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabindran SK, Ross DD, Doyle LA, Yang W, Greenberger LM. Fumitremorgin C reverses multidrug resistance in cells transfected with the breast cancer resistance protein. Cancer Res. 2000;60(1):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen JD, van Loevezijn A, Lakhai JM, van der Valk M, van Tellingen O, Reid G, et al. Potent and specific inhibition of the breast cancer resistance protein multidrug transporter in vitro and in mouse intestine by a novel analogue of fumitremorgin C. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1(6):417–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox E, Bates SE. Tariquidar (XR9576): a P-glycoprotein drug efflux pump inhibitor. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7(4):447–59. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robey RW, Steadman K, Polgar O, Morisaki K, Blayney M, Mistry P, et al. Pheophorbide a is a specific probe for ABCG2 function and inhibition. Cancer Res. 2004;64(4):1242–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kühnle M, Egger M, Müller C, Mahringer A, Bernhardt G, Fricker G, et al. Potent and selective inhibitors of breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) derived from the p-glycoprotein (ABCB1) modulator tariquidar. J Med Chem. 2009;52(4):1190–7. doi: 10.1021/jm8013822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larsen P, Ulin J, Dahlstrøm K, Jensen M. Synthesis of [11C]iodomethane by iodination of [11C]methane. Appl Radiat Isot. 1997;48(2):153–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jewett DM. A simple synthesis of [11C]methyl triflate. Appl Radiat Isot. 1992;43:1383–5. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(92)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loening AM, Gambhir SS. AMIDE: a free software tool for multimodality medical image analysis. Mol Imaging. 2003;2(3):131–7. doi: 10.1162/15353500200303133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luurtsema G, Molthoff CF, Schuit RC, Windhorst AD, Lammertsma AA, Franssen EJ. Evaluation of (R)-[11C]verapamil as PET tracer of P-glycoprotein function in the blood-brain barrier: kinetics and metabolism in the rat. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuntner C, Bankstahl JP, Bankstahl M, Stanek J, Wanek T, Dörner B, et al. Small-animal PET evaluation of [11C]elacridar and [11C]tariquidar in transporter knockout mice [symposium abstract] Nuklearmedizin. 2009;48(6):A143. [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vries NA, Zhao J, Kroon E, Buckle T, Beijnen JH, van Tellingen O. P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein: two dominant transporters working together in limiting the brain penetration of topotecan. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(21):6440–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polli JW, Olson KL, Chism JP, John-Williams LS, Yeager RL, Woodard SM, et al. An unexpected synergist role of P-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein on the central nervous system penetration of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib (N-{3-chloro-4-[(3-fluorobenzyl)oxy]phenyl}-6-[5-({[2-(methylsulfonyl)ethyl]amino}methyl)-2-furyl]-4-quinazolinamine; GW572016) Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37(2):439–42. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandema JW, Gubbens-Stibbe JM, Danhof M. Stability and pharmacokinetics of flumazenil in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;103(3):384–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02244294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shao X, Lisi JM, Butch ER, Kilbourn MR, Snyder SE. N-methylpiperidinemethyl, N-methylpyrrolidyl and N-methylpyrrolidinemethyl esters as PET radiotracers for acetylcholinesterase activity. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30(3):293–302. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]