Abstract

Quantitative studies in molecular and structural biology generally require accurate and precise determination of protein concentrations, preferably via a method that is both quick and straightforward to perform. The measurement of ultraviolet absorbance at 280 nm has proven especially useful, since the molar absorptivity (extinction coefficient) at 280 nm can be predicted directly from a protein sequence. This method, however, is only applicable to proteins that contain tryptophan or tyrosine residues. Absorbance at 205 nm, among other wavelengths, has been used as an alternative, although generally using absorptivity values that have to be uniquely calibrated for each protein, or otherwise only roughly estimated. Here, we propose and validate a method for predicting the molar absorptivity of a protein or peptide at 205 nm directly from its amino acid sequence, allowing one to accurately determine the concentrations of proteins that do not contain tyrosine or tryptophan residues. This method is simple to implement, requires no calibration, and should be suitable for a wide range of proteins and peptides.

Keywords: protein, absorbance, UV, concentration, molecular biology, absorptivity, extinction coefficient

Introduction

Accurate determination of protein concentration is essential for quantitative biochemical, biophysical, molecular, and structural biology studies. A wide range of spectrophotometric methods are available for doing so, each with its own advantages, disadvantages, and specific requirements.1 The absorbance of ultraviolet (UV) radiation by intrinsic chromophores is one commonly used method; particularly useful is absorbance at 280 nm (A280), which offers high specificity, as it arises strictly from tryptophan and tyrosine residues (and to a small extent from disulfide bonds if present). Thus, the molar absorptivity (extinction coefficient) for a protein at 280 nm (ε280) can be accurately estimated directly from its amino acid sequence.2–4 Absorbance at wavelengths other than 280 nm is also used less commonly, generally either in a non-sequence-specific manner or by calibrating absorbance data on a protein-by-protein basis. Calibration can be time-consuming and technically difficult, especially if it requires directly weighing lyophilized protein or peptide (which is confounded by the presence of any residual salt or water remaining in the dried protein). Other methods (e.g., Bradford, Lowry assays) that do not rely on intrinsic chromophores also require calibration and have the added disadvantage of requiring additional reagents and time. Thus, the ability to predict the molar absorptivity (e.g., at 280 nm) is advantageous in terms of both accuracy and efficiency.

If a protein contains no tyrosine or tryptophan residues, however, A280 cannot be used to determine the concentration of that protein in solution. One alternative is A205, which arises primarily from the peptide bond.5,6 Although the maximum absorbance of a protein actually occurs closer to 190 nm, A205 has been favored in part due to the technical limitations of measuring at lower wavelengths.6,7 Still, whereas most common buffers and solutions in biological research are essentially transparent at 280 nm, many solutes will exhibit some absorbance at 205 nm (although this effect is even more pronounced at lower wavelengths).1,5,8 Thus, one must consider, and carefully control for, any A205 stemming from the buffer alone, as described below. On the other hand, the much higher sensitivity of A205 relative to A280 offers an additional advantage that helps counteract this. The ratio of A205 to A280 is ∼30 on average, although it varies widely from protein to protein (and is virtually infinite for a protein lacking tryptophan and tyrosine residues).

Absorbance at 205 nm arises primarily from the peptide backbone. Thus, one can roughly estimate the concentration of a protein solution (in terms of mg·mL−1) without any knowledge of the protein sequence. A commonly used absorptivity value is ε205 = 31 mL·mg−1·cm−1.1,5,8 However, side chain absorbance at 205 nm is still significant; in particular, the aromatic side chains (tryptophan, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and histidine) all have a greater A205 than a single peptide bond. Considering this, Scopes6 proposed using the A280/A205 ratio for a given protein to estimate a more accurate ε205 (in effect taking into account tryptophan and tyrosine side chains). However, this does not include the contributions of phenylalanine, histidine, methionine, arginine, or cysteine/cystine, all of which absorb significantly at 205 nm. Thus, by taking into account the contributions of individual side chains to the overall A205, one can accurately and specifically (i.e., in a sequence-specific manner) determine the concentration of virtually any protein in solution, as we demonstrate in this report.

Results and Discussion

We measured the absorbance of six proteins and two peptides at both 205 nm and 280 nm to compare the values at these two wavelengths. Calmodulin (CaM) is a 148-residue calcium-binding protein,9 which has a predicted molar absorptivity at 280 nm of ε280 = 2980 M−1·cm−1 from two tyrosine residues and no tryptophan residues. Measurements were performed on both apo CaM and CaM saturated with four calcium ions (4Ca2+-CaM). Calmodulin-dependent kinase 1 (CaMK1), is a serine/threonine kinase that is activated by calcium-loaded CaM.10 One CaMK1 construct used in this study corresponds to the kinase domain (residues 1–296) and has a predicted ε280 of 42,860 M−1·cm−1 from four tryptophans and 14 tyrosines. The other CaMK1 construct (residues 299–320) is a short peptide corresponding to the CaM-binding domain of CaMK1, with a predicted ε280 of 5500 M−1·cm−1 from one tryptophan. The other peptide used in this study is the 26-residue M13 peptide derived from skeletal muscle myosin light-chain kinase (skMLCK),11 which also has a predicted ε280 of 5500 M−1·cm−1, based on one tryptophan. The remaining four proteins measured were the B1 domain of Streptococcal protein G (GB1), the talin2 F3 domain, maltose-binding protein (MBP), and Enzyme I. These range in size from 66 to 575 residues in length, and have predicted ε280 values ranging from 9970 M−1·cm−1 to 66,350 M−1·cm−1, stemming from multiple tryptophan and tyrosine residues.

For greatest accuracy, a wide range of half-log dilutions was measured, though in everyday practice such extensive measurement would not be necessary or even warranted. All dilutions were performed in water. The stocks of Enzyme I and the two short peptides were already in water, but the stocks of the other proteins used in this study were in other buffers, some with significant absorbance at 205 nm. In these cases, dilutions were also made of the buffer alone, so that its absorbance could be subtracted from that of the protein solution. Thus, although the buffers used for CaMK11–296 and 4Ca2+-CaM, for example, had undiluted A205 values of 23.74 and 27.45, respectively, we were still able to accurately and precisely measure the A205 of CaMK11–296 (uncorrected = 678.2, corrected = 654.5) and CaM (uncorrected = 665.6, corrected = 638.2) using water dilutions in the range of 1:1000 to 1:10,000 (Table I). The buffer used for apo CaM also had a relatively high absorbance of A205 = 31.21, but the other buffers had much lower absorbances (0.59–4.37). Regardless, buffer absorbance corrections were applied in all of these cases. However, no such corrections were needed for skMLCK, CaMK1299–320, or Enzyme I, as these stock solutions were already in water. Although one could instead ensure that solutes free of absorbance at 205 nm are used, our results show that this is unnecessary. In practice (as done here) one would ideally measure A205 values much greater for the protein than for the buffer solution alone, but at the very least, the difference between the two measurements must be significantly larger than the experimental error.

Table I.

Analysis of Data Collected for This Study

| Protein | MW (g·mol−1)a | ε280 (M−1·cm−1)b | A280c | A205 | Conc. (µM)d | εbb (M−1·cm−1)e | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measuredf | Correctedg | |||||||

| CaMK1299-320 | 2599 | 5500 | Averageh | 9.72 | 170.97 | 170.97 | 1767.96 | 2,704 |

| Errori | 0.97 | 5.36 | 5.36 | 176.49 | 482 | |||

| % Errorj | 9.98 | 3.13 | 3.13 | 9.98 | 17.8 | |||

| skMLCK | 2964 | 5500 | Averageh | 7.90 | 162.85 | 162.85 | 1436.12 | 2,838 |

| Errori | 0.63 | 8.63 | 8.63 | 114.70 | 435 | |||

| % Errorj | 7.99 | 5.30 | 5.30 | 7.99 | 15.3 | |||

| GB1 | 7246 | 9970 | Averageh | 5.72 | 152.40 | 151.80 | 573.53 | 3112 |

| Errori | 0.25 | 8.07 | 8.07 | 25.22 | 281 | |||

| % Errorj | 4.40 | 5.30 | 5.32 | 4.40 | 9.0 | |||

| talin2 | 11,558 | 16,960 | Averageh | 18.35 | 433.25 | 432.66 | 1081.99 | 2870 |

| Errori | 0.84 | 17.39 | 17.39 | 49.50 | 241 | |||

| % Errorj | 4.57 | 4.01 | 4.02 | 4.57 | 8.4 | |||

| apo CaM | 16,706 | 2890 | Averageh | 2.65 | 488.01 | 457.81 | 889.23 | 2716 |

| Errori | 0.09 | 39.26 | 39.26 | 30.87 | 324 | |||

| % Errorj | 3.47 | 8.05 | 8.58 | 3.47 | 11.9 | |||

| 4Ca2+-CaM | 16,706 | 2890 | Averageh | 3.86 | 665.60 | 638.15 | 1294.76 | 2567 |

| Errori | 0.03 | 37.45 | 37.45 | 11.60 | 199 | |||

| % Errorj | 0.90 | 5.63 | 5.87 | 0.90 | 7.8 | |||

| CaMK11-296 | 33,442 | 42,860 | Averageh | 25.25 | 678.19 | 654.45 | 589.03 | 2631 |

| Errori | 1.53 | 28.53 | 28.53 | 35.62 | 281 | |||

| % Errorj | 6.05 | 4.21 | 4.36 | 6.05 | 10.7 | |||

| MBP | 40,614 | 66,350 | Averageh | 1.81 | 45.37 | 41.00 | 27.21 | 2914 |

| Errori | 0.04 | 1.82 | 1.82 | 0.61 | 204 | |||

| % Errorj | 2.25 | 4.02 | 4.45 | 2.25 | 7.0 | |||

| Enzyme I | 63,467 | 24,410 | Averageh | 28.84 | 2267.58 | 2267.58 | 1181.66 | 2684 |

| Errori | 1.15 | 21.38 | 21.38 | 46.96 | 137 | |||

| % Errorj | 3.97 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 3.97 | 5.1 | |||

Molecular weight calculated from amino acid sequence; confirmed by mass spectrometry.

Molar absorptivity at 280 nm, calculated as described in Methods section.

Absorbance at 280 nm of undiluted protein solution, extrapolated from measurements on various dilutions.

Concentration calculated from absorbance at 280 nm.

Molar absorptivity at 205 nm per backbone peptide bond, calculated individually for each protein as described in the text.

Absorbance at 205 nm of undiluted protein solution, extrapolated from measurements on various dilutions.

Absorbance at 205 nm of buffer alone was subtracted from measurements on solution of buffer + protein.

Average of measured absorbance or calculated concentration values.

Standard deviation of absorbance measurements or calculated concentration.

% Error = (error/average) × 100%.

From the data collected at 205 nm and 280 nm, and under the assumption that the molar absorptivities calculated for 280 nm are correct, we estimated molar absorptivities at 205 nm for each of the polypeptides in this study, ranging from ε205 = 96,705 M−1·cm−1 (37.21 mL·mg−1·cm−1) for CaMK1299–320 to ε205 = 1,918,988 M−1·cm−1 (30.24 mL·mg−1·cm−1) for Enzyme I (Table II). Values of ε205 could be calibrated for any protein or peptide containing tryptophan or tyrosine in a similar manner, or using some other method for determining the concentration (e.g., directly weighing lyophilized powder) for those that do not. However, in this study we demonstrate that one can calculate the ε205 directly from the amino acid sequence, making such additional measurements or standards completely unnecessary.

Table II.

Comparison of Different Methods of Calculating Molar Absorptivity at 205 nm (ɛ205)

| Protein | ε205 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2801 | 31 mL·mg−1·cm−1b | Scopes methodc | New methodd | ||

| CaMK1299-320 | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 96,705 | 80,572 | 87,914 | 98,310 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 37.21 | 31 | 33.82 | 37.82 | |

| % Errorg | −16.68 | −9.09 | 1.66 | ||

| skMLCK | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 113,397 | 91,898 | 97,294 | 111,950 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 38.25 | 31 | 32.82 | 37.76 | |

| % Errorg | −18.96 | −14.20 | −1.28 | ||

| GB1 | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 264,682 | 224,623 | 228,392 | 243,070 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 36.53 | 31 | 31.52 | 33.55 | |

| % Errorg | −15.13 | −13.71 | −8.17 | ||

| talin2 | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 399,873 | 358,304 | 370,898 | 390,810 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 34.60 | 31 | 32.09 | 33.81 | |

| % Errorg | −10.40 | −7.25 | −2.27 | ||

| apo CaM | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 514,838 | 517,889 | 462,669 | 524,190 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 30.82 | 31 | 27.69 | 31.38 | |

| % Errorg | 0.59 | −10.13 | 1.82 | ||

| 4Ca2+-CaM | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 492,873 | 517,889 | 463,186 | 524,190 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 29.50 | 31 | 27.73 | 31.38 | |

| % Errorg | 5.08 | −6.02 | 6.35 | ||

| CaMK11-296 | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 1,111,071 | 1,036,715 | 1,057,752 | 1,155,120 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 33.22 | 31 | 31.63 | 34.54 | |

| % Errorg | −6.69 | −4.80 | 3.96 | ||

| MBP | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 1,506,589 | 1,259,043 | 1,311,224 | 1,457,280 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 37.10 | 31 | 32.28 | 35.88 | |

| % Errorg | −16.43 | −12.97 | −3.27 | ||

| Enzyme I | ε205 (M−1·cm−1)e | 1,918,988 | 1,967,462 | 1,810,473 | 1,973,840 |

| ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1)f | 30.24 | 31 | 28.53 | 31.10 | |

| % Errorg | 2.53 | −5.65 | 2.86 | ||

Molar absorptivity at 205 nm calculated directly from A280 data (ε205 = A205 × ε280/A280).

Molar absorptivity at 205 nm calculated from generic absorptivity of 31 mL·mg−1·cm−1 [ε205 (M−1·cm−1) = 31 (mL·mg−1·cm−1) × MW (g·mol−1)].

Absorptivity at 205 nm first calculated in mass units, as described by Scopes6 [ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1) = 27.0 + 120 × (A280/A205)], then transformed into molar units [ε205 (M−1·cm−1) = ε205 (mL·mg−1·cm−1) × MW (g·mol−1)].

Molar absorptivity calculated from the amino acid sequence as described in the main text; an interactive web server to carry out this calculation online is available at http://spin.niddk.nih.gov/clore.

Molar absorptivity at 205 nm calculated by various methods.

Absorptivity at 205 nm, given in alternative mass units [=ε205 (M−1·cm−1)/MW (g·mol−1)].

Percentage of deviation from ε205 value calculated directly from A280 data.

A great advantage of using A205 for determining protein concentration is that absorbance at 205 nm arises primarily from the peptide backbone, although side chains, and in particular aromatic ones, can contribute significantly. To take this into account, we referenced molar absorptivities at 205 nm given by Goldfarb et al.7 and Saidel et al.12 These reported molar absorptivities for individual amino acids ranged from 54 M−1·cm−1 (glycine) to 20,400 M−1·cm−1, though only those with ε205 > 200 M−1·cm−1 were included in this study (Table III). The literature, however, gives a wide range of values for the ε205 of the peptide bond, and Goldfarb et al.7 suggested a range of 2500–2800 M−1·cm−1 per peptide bond. This likely represents true variation stemming from local structure, rather than experimental error.7,13

Table III.

Molar Absorptivity Values at 205 nm (ɛ205) Used in This Study for Protein Side Chains and the Backbone Peptide Bond

| Side chain/feature | ε205 (M−1·cm−1) |

|---|---|

| Tryptophan | 20,400 |

| Phenylalanine | 8600 |

| Tyrosine | 6080 |

| Histidine | 5200 |

| Methionine | 1830 |

| Arginine | 1350 |

| Cysteine | 690 |

| Asparaginea | 400 |

| Glutaminea | 400 |

| Cystineb | 2200 |

| Backbone peptide bondc | 2780 ± 168 |

Values for asparagine and glutamine come from Saidel et al.12 All other values are from Goldfarb et al.7

If the protein has a disulfide bond, add 820 M−1·cm−1 (2200 M−1·cm−1 − 2 × 690 M−1·cm−1) to its ε205.

Best-fit value determined as described in the text and given as the average ±1 standard deviation.

Due to the above uncertainty, we asked whether we could find an averaged value of ε205 for the peptide bond (εbb) that would be generally applicable, keeping in mind that in reality the actual value per peptide bond is probably quite variable. From our data on eight different polypeptides, we found an overall best-fit εbb of 2780 ± 168 M−1·cm−1, which is within the previously reported range.7 The values calculated for individual peptides ranged from 2567 to 3112 M−1·cm−1 (Table I). Using the average value of εbb = 2780 M−1·cm−1, we calculated a value of ε205 for each polypeptide in this study by summing all of the backbone and side chain contributions, as described in the methods. These values are presented in the rightmost column of Table I. Compared to the concentrations determined from A280, the ε205 values based on εbb = 2780 M−1·cm−1 give errors in concentration of at most 8.2% (GB1), though for all but two (GB1 and 4Ca2+-CaM) the error is less than 4% (Table II) and well within experimental error (Table I). If, however, one uses a non-sequence-specific estimate for ε205 of 31 mL·mg−1·cm−1, the errors are in general much larger (up to 19.0%). Even using the formula put forth by Scopes,6 these errors are only slightly reduced to a maximum of 14.2% (Table II). Only for 4Ca2+-CaM do both of the generic methods give lower errors than the new sequence-specific method, though the differences in error between these methods (6.4% vs. 5.1% vs. 6.0%) are negligible. For apo CaM and Enzyme I, the generic 31 mL·mg−1·cm−1 value gives a slightly lower error than the sequence-specific value, but the difference in errors (1.8% vs. 0.59% for apo CaM, 2.9% vs. 2.5% for Enzyme I) are miniscule and well within the experimental error. In all other cases, the sequence-specific value of ε205 gives the lowest error, often dramatically so.

Based on the data presented here, this method works well for both folded proteins and short unstructured peptides. Although the majority of the A205 in all cases comes from the peptide backbone, the actual contribution for these test cases ranges from 59.4% (CaMK1299–320) to 80.8% (Enzyme I). Thus, one can see why calculating sequence-specific molar absorptivities would be advantageous, since side chains can be responsible for up to 40% of the total A205 in these instances. Additionally, measuring data on both apo CaM and 4Ca2+-CaM offered the opportunity to test whether structural changes within the same protein affect A205. Although these two conditions gave slightly different results (εbb = 2716 ± 324 M−1·cm−1 for apo CaM and 2567 ± 199 M−1·cm−1 for 4Ca2+-CaM), these differences were within the experimental error.

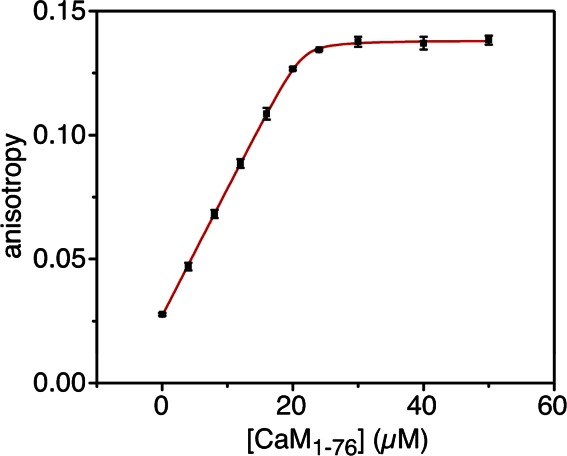

To test the utility of the A205 method for determining protein concentration using sequence-specific calculated molar absorptivities, we performed a concentration-dependent experiment on a protein construct that does not absorb at 280 nm. The N-terminal domain of CaM (CaM1–76) does not contain any 280 nm-absorbing residues (both tyrosines are located in the C-terminal domain). Using the method described here, CaM1–76 has a calculated ε205 of 266,150 M−1·cm−1. We determined the concentrations of CaM1–76 and skMLCK by A205 and then performed a fluorescence anisotropy binding experiment. This titration experiment yielded a CaM1–76:skMLCK stoichiometry of 2.13(±0.17):1 (Fig. 1), well within the experimental error of the expected value of 2:1.14 (Note that whereas the stoichiometry of the full-length CaM:skMLCK interaction is 1:1—with the N and C domains of CaM participating in the interaction11—in isolation, individual domains of CaM bind with a 2:1 stoichiometry, because a second CaM1–76 molecule, in this case, takes the place of the absent C-terminal CaM domain in the complex.14)

Figure 1.

Testing the stoichiometry of 2Ca2+-CaM1–76 binding to the skMLCK M13 peptide. Fluorescence anisotropy was measured for the tryptophan of skMLCK alone (10 µM) and in the presence of 0–50 µM CaM1–76. Experimental data (average of three measurements) are plotted as filled-in squares, with error bars indicating one standard deviation. The best-fit line is shown in red. The CaM1–76:skMLCK stoichiometry from the fit of the data is n = 2.13 ± 0.17, which is in excellent agreement with the literature value of 2:1.14 The titration was performed with [skMLCK] >> KD to most accurately determine the stoichiometry. The effective KD from the fit is 100 ± 28 nM, several orders of magnitude weaker than the value determined for full-length CaM (∼50 pM).20

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the utility of a method for determining protein concentrations from absorption at 205 nm, using a molar absorptivity calculated specifically from the amino acid sequence. This method allows one to easily and quickly determine protein concentration when there are no tryptophan or tyrosine residues present. It is generally applicable, requiring no additional standards or other calibration, and we have made this tool available on the web (at http://spin.niddk.nih.gov/clore) to assist in calculating ε205 for any protein or peptide. We have also shown that taking the amino acid sequence into account is essential for accurate results, and we believe that this method will be widely applicable.

Methods

Protein production and sample preparation

All proteins were produced recombinantly in Escherichia coli (with the exception of the two peptides that were commercially synthesized as described below). The 148-residue human calmodulin (CaM) protein was expressed and purified as described previously from a construct in a pET21a vector.9 Experiments were performed on CaM in a buffer consisting of 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)−1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 6.5, 100 mM KCl, 0.02% sodium azide, 1× Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor, and either 8 mM CaCl2, (4Ca2+-CaM) or 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and 2 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (apo CaM). A construct corresponding to the N-terminus of CaM (residues 1–76; CaM1–76) was generated using the QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies), and expressed and purified like full-length CaM. The skMLCK M13 peptide (KRRWKKNFIAVSAANRFKKISSSGAL) and the peptide corresponding to the CaM-binding domain of CaMK1 (residues 299–320; AKSKWKQAFNATAVVRHMRKLQ) were commercially synthesized by Anaspec. They were resuspended in water from lyophilized powder for the experiments here.

The B1 domain of streptococcal protein G (66 residues) was expressed from a construct in a GEV2 vector, as previously described.15 Experiments were performed in a buffer consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5, and 100 mM NaCl. The F3 domain of human talin2 (residues 311–408) was expressed from a construct in a pGEX-6P-2 vector, as previously described.16 Experiments were performed in a buffer consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, and 100 mM NaCl. A mutant of E. coli MBP (370 residues; K1A K46C I212C) was expressed from a construct in a pET11 vector, as previously described.17 Experiments were performed in a buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). A mutant of E. coli Enzyme I (residues 1–575; H189A R367K) was expressed from a construct in a pET11 vector, as previously described.18 Experiments were performed in H2O.

DNA corresponding to the full-length 374-residue calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type 1 (CaMK1) protein from rat was synthesized (codon-optimized for expression in E. coli) by Genscript (http://www.genescript.com) and subcloned into the pET47b vector. A construct corresponding to residues 1–296 was generated using the QuikChange II kit. CaMK1 was expressed in BL21-Star cells (Agilent Technologies) using standard methods. Briefly, cells were grown at 37°C in 1 L of Luria Bertini (LB) medium to OD600nm (optical density) ∼ 0.6, cooled to 25°C, and induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d−1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were harvested by centrifugation ∼16 h later. Cells were resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 1× Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor. Cells were lysed using a microfluidizer, cleared by centrifugation, and then loaded on a HisTrap column (GE Life Sciences). Protein was eluted with a 0–100% gradient over five column volumes with the same buffer containing 500 mM imidazole. The protein was cleaved ∼20 h at 4°C with 3C protease, then further purified by gel filtration on a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 column (GE Life Sciences) into a buffer consisting of 25 mM HEPES, pH 6.5, 100 mM KCl, 0.02% sodium azide, and 0.1× Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor. Fractions were concentrated with Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter Units (10 kDa molecular weight cutoff).

3C Protease was expressed as a GST fusion (from a pGEX vector) in BL21 CodonPlus cells (Agilent Technologies). Cells were grown at 37°C in 1 L of LB medium to OD600nm ∼ 0.6, cooled to 25°C, and induced with 0.2 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested by centrifugation ∼16 h later and resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT. Cells were lysed using a microfluidizer, cleared by centrifugation, and then loaded on a GSTrap column (GE Life Sciences). Protein was eluted with 30 mM reduced glutathione. Aliquots were stored at −80°C in elution buffer.

Absorbance measurements

Absorbance values at 205 nm and 280 nm were measured on an Agilent 8453 UV/Vis spectrophotometer, using a quartz cuvette with a 1 cm path length. For all samples, dilutions were performed in water (due to the high UV absorbance of some of the buffers used). Absorbance was measured at various dilutions in half-log increments, and all measurements within a linear range for absorbance versus concentration were averaged (after extrapolating the undiluted absorbance value by multiplying by the dilution factor). The absorbance values of the buffers alone were also measured in the same manner. For all samples, the final A205 used for protein concentration determination was the average extrapolated A205 for the undiluted protein solution minus the A205 for the buffer alone (Table I).

Calculation of molar absorptivities

Absorbance (Aλ) at a given wavelength λ is given by the Beer–Lambert law:

| (1) |

where ελ is the molar absorptivity at wavelength λ, c the concentration, and l the path length (always 1 cm in this study). For measurements at 280 nm, the ε280 was calculated by adding 5500 M−1·cm−1 for each tryptophan and 1290 M−1·cm−1 for each tyrosine, based on standard literature values.2–4,19

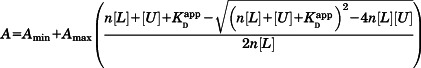

For measurements at 205 nm, the absorbance of both the peptide backbone and side chains were taken into account. The values used for each side chain are given in Table III and were taken from literature values (Goldfarb et al.7 for all values, with the exception of the values for glutamine and asparagine, which came from Saidel et al.12). The molar absorptivity at 205 nm (ε205) for a polypeptide is given by the formula:

| (2) |

where for each amino acid type i, εi is the molar absorptivity of that amino acid type (Table III), ni is the number of times that amino acid type appears in the polypeptide sequence, εbb is the molar absorptivity for a single backbone peptide bond, and r is the number of residues in the polypeptide sequence.

A standard value for the absorbance of the peptide bond could not be chosen a priori from the literature, so instead one was determined empirically. This was accomplished first by calculating a value of ε205 for each polypeptide in the study:

| (3) |

where ε280 is the known molar absorptivity at 280 nm for that polypeptide, and A205 and A280 are the absorbance data for that polypeptide (Table I). These A280-based ε205 values are presented in the leftmost data column of Table II. For each polypeptide, a value of εbb was then calculated by rearrangement of Eq. (2):

| (4) |

These values of εbb are presented in Table I. An overall best-fit value of εbb was then computed by averaging the εbb values for the individual polypeptides. The use of this single optimized value (determined to be 2780 ± 168 M−1·cm−1 in this case) is not meant to imply that each peptide bond always displays the same absorbance value (since the absorbance of the peptide bond is know to be quite variable7,13) but rather that the use of this one value is sufficiently reliable to be generally useful.

Thus, using a value of εbb = 2780 M−1·cm−1, ε205 can be calculated for any protein or peptide directly from its amino acid sequence, using Eq. (2). For the polypeptides used in this study, ε205 values calculated in this manner are presented in the rightmost column of Table II. A web server that performs this calculation can be accessed online at http://spin.niddk.nih.gov/clore. This tool also calculates the molecular weight for various universal isotopic labeling schemes that might be used in nuclear magnetic resonance studies.

Fluorescence experiments

Fluorescence experiments were carried out at 27°C using a Jobin Ybon FluoroMax-3 fluorometer equipped with a Peltier temperature control unit. The fluorescence anisotropy of the single tryptophan residue in the skMLCK peptide was monitored with excitation at 295 nm and emission at 357 nm. Measurements were acquired on 10 µM skMLCK in the presence of 0–50 µM 2Ca2+-CaM1–76. Experiments were performed in 25 mM HEPES, pH 6.5, 100 mM KCl, 8 mM CaCl2, and 0.1× Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor. Data were analyzed by fitting the fluorescence anisotropy versus [CaM1–76] to the following equation:

|

(5) |

where A is the measured fluorescence anisotropy at each point (the dependent variable in the fitting), Amax the anisotropy of the skMLCK peptide fully saturated with CaM1–76, Amin the anisotropy of the free skMLCK peptide, n the stoichiometry of CaM1–76:skMLCK binding, [L] the total (bound + unbound) concentration of the skMLCK peptide, [U] the total (bound + unbound) concentration of CaM1–76 at each point (the independent variable in the fitting), and the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant, defined as:

the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant, defined as:

| (6) |

is only equal to the true dissociation constant for the case where the stoichiometry is n = 1; otherwise it represents an effective KD (i.e., concentration at half saturation). Experiments were carried out under conditions where [L] >> KD to most accurately fit the stoichiometry. Data were fit using OriginPro 8.

is only equal to the true dissociation constant for the case where the stoichiometry is n = 1; otherwise it represents an effective KD (i.e., concentration at half saturation). Experiments were carried out under conditions where [L] >> KD to most accurately fit the stoichiometry. Data were fit using OriginPro 8.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Libich for useful discussions and Vincenzo Venditti for providing purified MBP and Enzyme I.

References

- 1.Stoscheck CM. Quantitation of protein. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:50–68. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82008-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edelhoch H. Spectroscopic determination of tryptophan and tyrosine in proteins. Biochemistry. 1967;6:1948–1954. doi: 10.1021/bi00859a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill SC, von Hippel PH. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to measure and predict the molar absorption coefficient of a protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimsley GR, Pace CN. Spectrophotometric determination of protein concentration. Curr Protoc Protein Sci Chapter. 2004;3:Unit 3 1. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps0301s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scopes RK. Measurement of protein by spectrophotometry at 205 nm. Anal Biochem. 1974;59:277–282. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldfarb AR, Saidel LJ, Mosovich E. The ultraviolet absorption spectra of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonian MH. Spectrophotometric determination of protein concentration. Curr Protoc Toxicol Appendix. 2004;3:A 3G 1–7. doi: 10.1002/0471140856.txa03gs21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anthis NJ, Doucleff M, Clore GM. Transient, sparsely populated compact states of apo and calcium-loaded calmodulin probed by paramagnetic relaxation enhancement: interplay of conformational selection and induced fit. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18966–18974. doi: 10.1021/ja2082813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg J, Nairn AC, Kuriyan J. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I. Cell. 1996;84:875–887. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikura M, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM, Zhu G, Klee CB, Bax A. Solution structure of a calmodulin-target peptide complex by multidimensional NMR. Science. 1992;256:632–638. doi: 10.1126/science.1585175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saidel LJ, Goldfarb AR, Waldman S. The absorption spectra of amino acids in the region two hundred to two hundred and thirty millimicrons. J Biol Chem. 1952;197:285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenheck K, Doty P. The far ultraviolet absorption spectra of polypeptide and protein solutions and their dependence on conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1961;47:1775–1785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.11.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barth A, Martin SR, Bayley PM. Specificity and symmetry in the interaction of calmodulin domains with the skeletal muscle myosin light chain kinase target sequence. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2174–2183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koenig BW, Rogowski M, Louis JM. A rapid method to attain isotope labeled small soluble peptides for NMR studies. J Biomol NMR. 2003;26:193–202. doi: 10.1023/a:1023887412387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anthis NJ, Wegener KL, Ye F, Kim C, Goult BT, Lowe ED, Vakonakis, Bate N, Critchley DR, Ginsberg MH, Campbell ID. The structure of an integrin/talin complex reveals the basis of inside-out signal transduction. EMBO J. 2009;28:3623–3632. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang C, Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Open-to-closed transition in apo maltose-binding protein observed by paramagnetic NMR. Nature. 2007;449:1078–1082. doi: 10.1038/nature06232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwieters CD, Suh JY, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Takayama Y. Clore GM Solution structure of the 128 kDa enzyme I dimer from Escherichia coli and its 146 kDa complex with HPr using residual dipolar couplings and small- and wide-angle X-ray scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 132:13026–13045. doi: 10.1021/ja105485b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkins MR, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Sanchez JC, Williams KL, Appel RD, Hochstrasser DF. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol Biol. 1999;112:531–552. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grishaev A, Anthis NJ, Clore GM. Contrast-matched small-angle X-ray scattering from a heavy-atom-labeled protein in structure determination: application to a lead-substituted calmodulin–peptide complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:14686–14689. doi: 10.1021/ja306359z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]