Abstract

Glass formation in the CaO–Al2O3 system represents an important phenomenon because it does not contain typical network-forming cations. We have produced structural models of CaO–Al2O3 glasses using combined density functional theory–reverse Monte Carlo simulations and obtained structures that reproduce experiments (X-ray and neutron diffraction, extended X-ray absorption fine structure) and result in cohesive energies close to the crystalline ground states. The O–Ca and O–Al coordination numbers are similar in the eutectic 64 mol % CaO (64CaO) glass [comparable to 12CaO·7Al2O3 (C12A7)], and the glass structure comprises a topologically disordered cage network with large-sized rings. This topologically disordered network is the signature of the high glass-forming ability of 64CaO glass and high viscosity in the melt. Analysis of the electronic structure reveals that the atomic charges for Al are comparable to those for Ca, and the bond strength of Al–O is stronger than that of Ca–O, indicating that oxygen is more weakly bound by cations in CaO-rich glass. The analysis shows that the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals occurs in cavity sites, suggesting that the C12A7 electride glass [Kim SW, Shimoyama T, Hosono H (2011) Science 333(6038):71–74] synthesized from a strongly reduced high-temperature melt can host solvated electrons and bipolarons. Calculations of 64CaO glass structures with few subtracted oxygen atoms (additional electrons) confirm this observation. The comparable atomic charges and coordination of the cations promote more efficient elemental mixing, and this is the origin of the extended cage structure and hosted solvated (trapped) electrons in the C12A7 glass.

Keywords: amorphous network, glass topology, electron localization

According to the glass formation theories of Zachariasen and Sun, CaO–Al2O3 (CA) liquids are unlikely to vitrify based on network and chemical bond strength considerations (1, 2). Al2O3 does not typically act as a network former but can assist in glass formation, whereas Ca is usually a modifier with a high (>6) oxygen coordination number. A detailed understanding of the structure–electronic–property relations is important given that CA-based glasses have potential applications as infrared optics, windows, laser hosts (3), and photomemory materials (4–8). The C12A7 composition glass, in particular, has been found to be very important in synthesizing the stable electride glass from a strongly reduced high-temperature melt to form persistent solvated electrons (9, 10).

CA has a narrow glass formation range around the eutectic composition of 64 mol % CaO–36 mol % Al2O3 (64CaO glass) when one applies a conventional melt-quench method, although a wider range of 40–60 mol % CaO composition glass can be obtained by splat quench or containerless methods. McMillan and Piriou (11) carried out Raman spectroscopic measurements on CA glasses and crystals, and found that they comprise a fully polymerized network of AlO4 units at 50 mol % composition. The polymerized network is depolymerized by the addition of CaO between 60 and 70 mol % CaO composition. McMillan et al. (12) performed 27Al NMR measurements on CA glasses and found that Al2O3-poor composition glass has only fourfold coordinated Al atoms. Recent high-resolution NMR techniques (13) detected the formation of ∼5% OAl3 triclusters (oxygen coordinating three Al atoms) in 50 mol % CaO–50 mol % Al2O3 glass (50CaO glass), which are abundant in liquid Al2O3 and may obstruct the vitrification process.

Numerous diffraction studies on glasses and liquids (14–18) have been carried out using X-rays and neutrons to probe atomic structure and, in particular, atomic distance and coordination numbers around aluminum and calcium. Recently classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been performed on glasses and liquids (18–20). As summarized in refs. 16 and 19, there are serious discrepancies among diffraction, NMR, and MD simulations in the exact value of the average oxygen coordination number around Al (4–4.8) and Ca atoms (4–6.2). In a different context, first-principles MD simulations of the solvation of calcium ions have revealed that the Ca coordination has several shallow minima (5–8), which enables variable hydration structure (21).

Recently, we combined density functional theory (DFT) and reverse Monte Carlo (RMC) (22) simulations to study atomic and electronic structure in glass network on the basis of large-scale atomic configurations that are consistent with diffraction data. This approach revealed an unusually small Mg–O coordination number and glass topology in MgO–SiO2 compounds (23). Here, we apply this technique to derive reliable structural models and to understand the origin of glass formation in CA glasses, which is of interest because the systems comprise no traditional glass-forming cations. We have modeled and analyzed large atomic configurations of 50CaO and 64CaO glasses using a combined DFT–RMC technique based on published pulsed neutron diffraction data (24) and newly measured high-energy X-ray diffraction and X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) data obtained at the calcium K absorption edge. Special attention is paid to coordination numbers around oxygen as well as cation–oxygen coordination numbers, bond angles, ring statistics, electronic structure, and the relationship between glass structure and glass-forming ability (GFA).

The excess electrons in liquids have been excessively studied for several decades, and one of the most prevalent fields that has considered hydrated electrons is aqueous solutions. It has been suggested based on DFT simulations that the excess “solvated” electrons in water occupy cavity sites that form and annihilate spontaneously (25). While another simulation study concludes a reverse phenomenon where the electron is usually accompanied by an enhanced local water density of ∼1 nm, the existence of excess electrons in cavities could not be solely excluded (26). Most recently, new theoretical results in favor of the cavity sites have been demonstrated (27). Here, we also discuss the occurrence of excess electrons in the solid state, namely the CA electride glass as proposed by Kim et al. (10), and we demonstrate by DFT simulations how additional electrons occupy individual cages or small cavities in the glass structure providing unique electronic properties.

Sample Preparation and Density Measurement

The details of sample preparation are described in refs. 16 and 24. The measurement of density was performed using a dry pycnometer (Shimadzu Accupyc II 1340).

XAFS Measurement

The calcium K-edge XAFS measurements of 50CaO and 64CaO glasses were carried out at the BL01B1 beamline of SPring-8. The incident X-ray beam was monochromatized by a Si (111) double-crystal monochromator. The higher harmonics in the incident X-ray beam was removed by rhodium-coated mirrors. Vertical focusing of the incident beam at the sample was performed by the spherically bent second mirror.

High-Energy X-Ray Diffraction Measurement

The high-energy X-ray diffraction experiments on 50CaO and 64CaO glasses were carried out at room temperature. The incident X-ray energy was 61.5 kilo electron volt (keV). The diffraction patterns of glass beads of ∼2–3 mm were measured in transmission geometry. The intensity of incident X-rays was monitored by an ionization chamber filled with Ar gas, and the scattered X-rays were detected by a Ge detector. A vacuum chamber was used to suppress the air scattering around the sample, and the data collected were corrected using a standard program (28).

DFT–RMC Simulations

RMC modeling of the 50CaO and 64CaO glasses was performed using the RMC++ code (29). The starting configuration was created using hard-sphere Monte Carlo (HSMC) simulations with constraints applied to avoid physically unrealistic structures. Two kinds of constraints were used: closest atom–atom approach and connectivity. The choices of the closest atom–atom approaches were determined to avoid unreasonable spikes in the partial pair correlation functions. The constraint on the Al–O connectivity was that all aluminum atoms were coordinated to four oxygen atoms up to 2.1 Å, but no constraint on the Ca–O connectivity was applied. After the HSMC simulations, several RMC simulations containing X-ray S(Q), neutron S(Q), and k3·χ(k) extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) data were performed and the successful models were selected based on DFT calculations. The number of particles was 1,078 for both glasses, and the atomic number density used was 0.0768 Å–3 and 0.0746 Å–3 for the 50CaO and 64CaO glass, respectively. Following the RMC simulations, the geometry optimizations, MD simulations at 300 K, and electronic structure calculations of the 50CaO and 64CaO glasses were performed using the CP2K program (30, 31) in the DFT mode. The overall energy decreases of the final structures (DFT) with respect to the initial HSMC and RMC models were 1.1 eV/atom and 0.6 eV/atom, respectively, for both glass compositions.

The CP2K program is formally linearly scaling as a function of the system size and enables DFT simulations of systems up to 1,000 atoms or more. This is crucial for amorphous (glassy) materials as it is desirable to reduce the effects of the finite simulation cell (periodic boundary conditions) by increasing the system size and improving the statistics by including more atoms. CP2K employs two representations of the electron density: localized Gaussian and plane wave (GPW) basis sets. For the Gaussian-based (localized) expansion of the Kohn–Sham orbitals, we use a library of contracted molecularly optimized valence double-zeta plus polarization (m-DZVP) basis sets (32), and the complementary plane wave basis set has a cutoff of 600 Rydberg for electron density. The valence electron–ion interaction is based on the norm-conserving and separable pseudopotentials of the analytical form derived by Goedecker, Teter, and Hutter (33), and the generalized gradient-corrected approximation of Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE) is adopted for the exchange–correlation energy functional (34). The average cohesive energies of the DFT-optimized crystalline structures of CaAl2O4 (448 atoms) and 12CaO·7Al2O3 (472 atoms) are 5.86 and 5.77 eV/atom, respectively, and the crystalline phase is 0.15 and 0.16 eV/atom more stable than glass. The optimized crystalline geometries are very close to the experimental structures of CaAl2O4 (35) and 12CaO·7Al2O3 (36), and the average Ca–O distances are within 0.01 Å from the experimental values (maximum individual deviation 0.05 Å). Furthermore, the performance of the PBE functional has been thoroughly tested for calcium hydrates in ref. 37, and it results in satisfactory results for both energetics and structure. More details of the DFT–RMC approach are provided in SI Text.

Results and Discussion

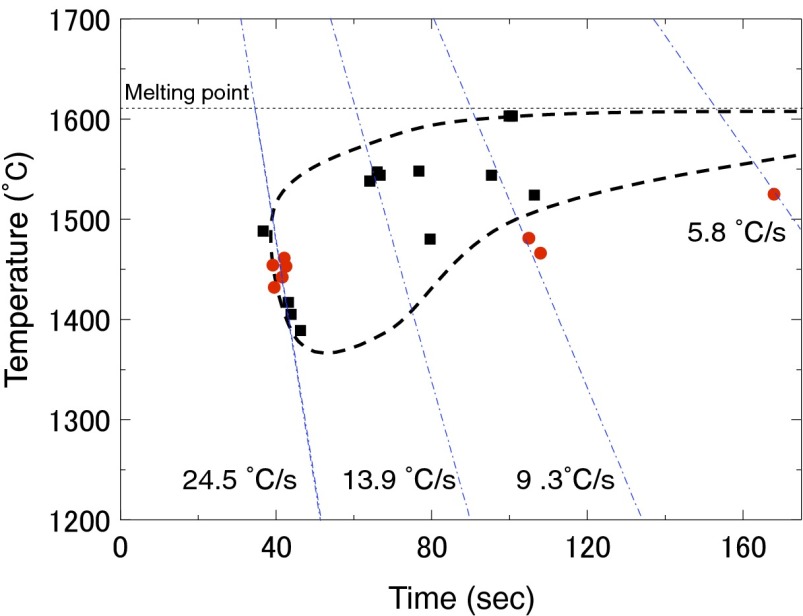

Continuous-cooling-transformation (CCT) curve measurements were performed to evaluate the GFA of CaO–Al2O3, and the results for 50CaO are shown in Fig. 1.The CCT curves were estimated from the cooling curves of levitated melts. Initially, the levitated melt was kept at 2,500 °C in the aerodynamic levitation furnace, and the CO2 laser power was then decreased at a constant speed (5.8–24.5 °C/s). When crystallization occurred, the temperature of the melt increased rapidly before decaying, and the peak temperature was regarded as the crystallization temperature. In addition, the vitrification temperature could be determined since the cooling curve showed the inflection point. Crystallization was observed to occur starting from the 50CaO melt but not from the 64CaO melt under identical conditions. These measurements directly indicate that GFA of 50CaO is lower than that of 64CaO.

Fig. 1.

CCT curve for the 50CaO glass. Squares and circles represent the solidification temperature for the crystalline and glassy phases, respectively. Dashed curve shows the boundary between crystallization and vitrification.

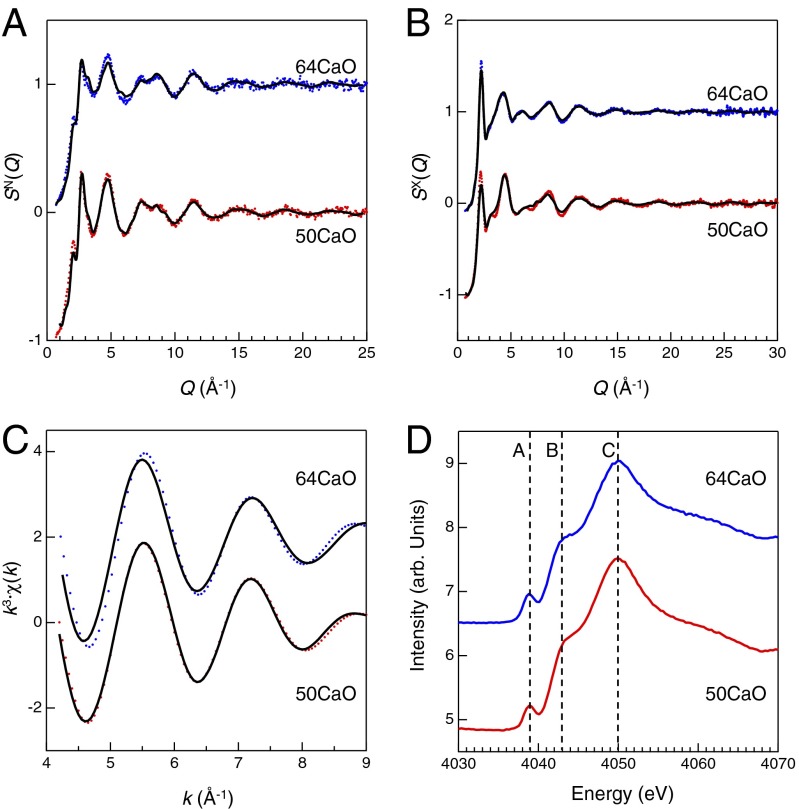

Fig. 2 A–C shows experimental neutron and X-ray total structure factor SN,X(Q) and EXAFS k3·x(k) data of 50CaO glass and 64CaO glass as colored dots. The difference between the two compositions is small in both diffraction and EXAFS data, suggesting that short-range structure is similar between the compositions. Fig. 2D shows the Ca K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra of 50CaO and 64CaO glasses. There are no significant differences in the XANES spectra between the glasses, which is consistent with the k3·x(k) data.

Fig. 2.

Neutron (A) and X-ray (B) total structure factors S(Q) and EXAFS k3·χ(k) (C) for 50CaO glass (red) and 64CaO glass (blue). The EXAFS k3·χ(k) were obtained by back Fourier transformation of |FT| of the first correlation peak. The original k3·χ(k) data are shown in Fig. S1. Colored circles, experimental data; black curve, DFT–RMC model. (D) The XANES spectra for 50CaO glass (red) and 64CaO glass (blue). XANES and k3·χ(k) XAFS spectra were measured at Ca K-edge. The dashed lines are a guide for the eyes. A pre-edge peak A observed at 4,039 eV corresponds to 1s ➔ 3d + np transition (45, 46), which can be related to the geometry and distortion of the Ca site. The main resonance peak C and shoulder B observed at 4,050 eV and 4043 eV, respectively, correspond to 1s ➔ 4p transition (45, 47).

To uncover the origin of higher GFA of 64CaO glass in comparison with the 50CaO composition glass, we compute the atomic and electronic structure of both CA glasses by large-scale DFT–RMC simulations using X-ray, neutron, and EXAFS data. To obtain a reliable structural model using our approach, we measured the density, since it is an important parameter for the structural analysis of CA glasses over this wide composition range. Also, the earlier available density data were not systematic, and there are some discrepancies among measurements (24). Our new density value (Fig. S2) measured by a dry pycnometer increases with increasing CaO content, and no critical point is observed. This trend is different from the result of a recent MD simulation (19). The results of our DFT–RMC simulation on the basis of new density data are compared with diffraction and EXAFS data in Fig. 2 A–C (the data from the DFT–RMC models are shown as black curves). The agreement with experimental X-ray structure factors, SX(Q), neutron structure factors, SN(Q), and EXAFS k3·x(k) is very good, giving us confidence for the structural models. It is worth mentioning that—despite experimental constraints—the final DFT–RMC models are only 0.09 and 0.06 eV/atom higher in total energy than the corresponding DFT minima (base structures for the RMC refinement after MD and geometry optimization).

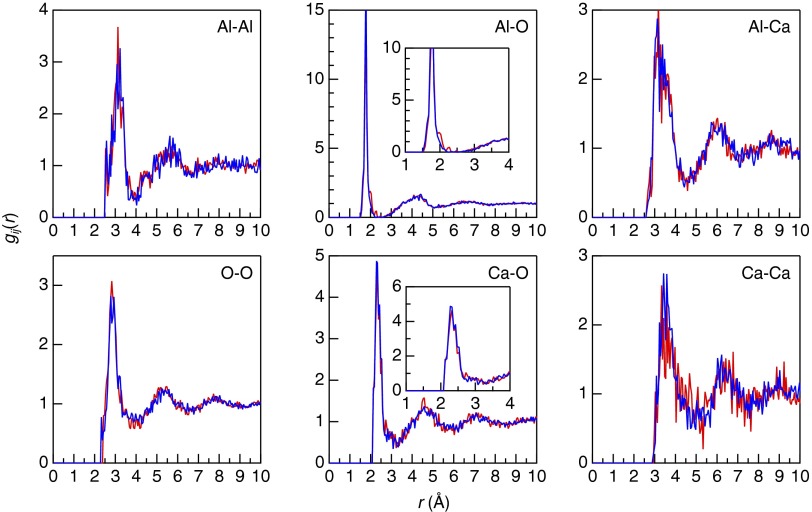

The partial pair correlation functions, gij(r), of CA glasses obtained from the DFT–RMC simulation are shown in Fig. 3. We used a large-scale atomic configuration of 1,078 atoms, providing good statistics in real space. Both the first Al–O and Ca–O correlation peaks show a well-defined sharp peak due to the formation of Al–O and Ca–O bonds. It is of note that the difference between 50CaO glass and 64CaO glass is very small, suggesting that atomic correlations are very similar. This behavior is consistent with the partial structure factors, Sij(Q), obtained from DFT–RMC simulations (Fig. S3), where the data are similar for the two glasses.

Fig. 3.

Partial pair correlation functions gij(r) for the 50CaO (red) and 64CaO glass (blue) obtained by DFT–RMC simulation. The first Al–O and Ca–O correlation peaks are enlarged in inset for clarity.

To understand the short-range atomic correlations in detail, coordination numbers were calculated and are summarized in Table S1. The coordination number of oxygen around aluminum, NAl–O, calculated up to 2.5 Å, is 4.26 for 50CaO glass and 4.14 for 64CaO glass. The NCa–O calculated up to 2.8 Å is 5.02 for 50CaO glass and 4.92 for 64CaO glass. Thus, our DFT–RMC model strongly suggests that Al–O coordination and Ca–O coordination are similar for the two glass compositions. Although our Ca–O coordination number is different from that reported by neutron diffraction (38) and recent MD simulations (19, 20, 38), we note that experimentally the Ca coordination contains several overlapping correlations beyond 2.8 Å and our analysis used a significantly shorter high-r cutoff for the integration limit than ref. 38. Our total Ca–X coordination number (including Ca–O and Ca–Al interactions) calculated out to 3.0 Å is 6.4, in good agreement with the first order neutron difference results of ref. 38. In addition, the previously used MD atomic interaction potentials all have a 50% higher effective charge associated with Al than for Ca (19, 20, 38) contrary to our DFT findings. Furthermore, NCaO ∼ 5 is close to the result obtained by a combination of X-ray and neutron diffraction (15, 16), and reproduced by DFT simulations in the present work. On the other hand, the NO–O of 64CaO glass is substantially smaller than that in 50CaO glass due to the decreased number of OAl3 triclusters (O coordinated by three Al) (Fig. 4D), which are abundant in liquid Al2O3 and signatures of low GFA. The fraction of OAl3 triclusters formed by tetrahedral Al alone is 14.5% for 50CaO glass and 9% for 64CaO glass in our models. These values are slightly higher than the values reported by Drewitt et al. (18) for the liquid, and the NMR results for the 50CaO glass (13).

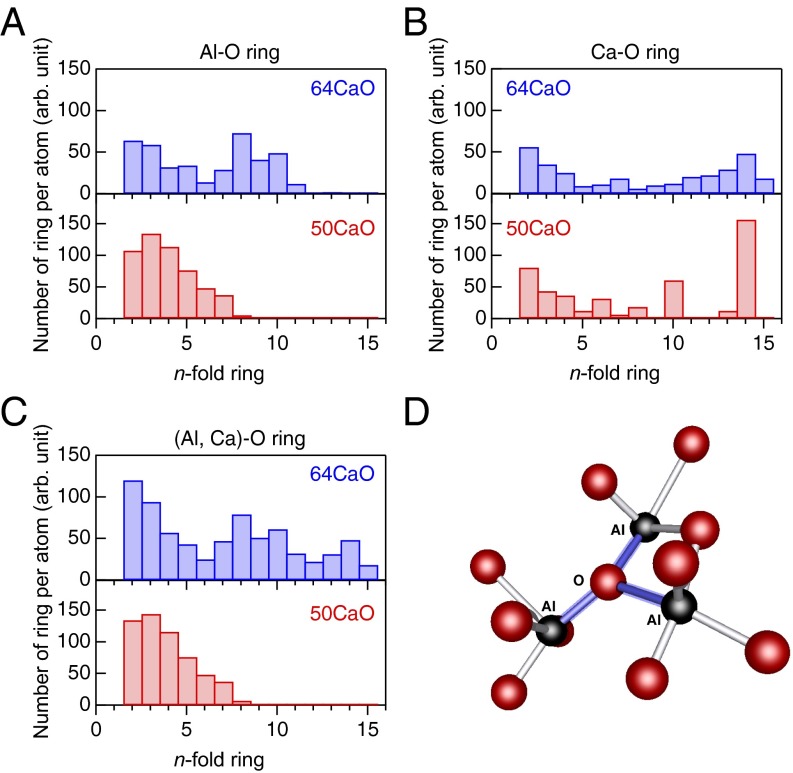

Fig. 4.

The ring size distribution for (A) Al–O rings, (B) Ca–O rings, and (C) (Al, Ca)–O rings calculated from the DFT–RMC models of the 50CaO (red) and 64CaO glass (blue) and a schematic view of OAl3 tricluster (D). The Ca–O ring statistics do not show a typical Gaussian distribution, implying that ring structures alone do not represent the nature of the Ca–O bonding.

The most striking feature is the coordination number of cations around oxygen. The NO–Al and NO–Ca values are 2.13 and 1.25, respectively, for 50CaO glass, and 1.73 and 1.83 for 64CaO glass. For the latter compound, oxygen is surrounded by similar number of Al and Ca atoms. This similarity arises from the Al–O coordination being slightly larger than 4 and the Ca–O coordination being close to 5; for comparison, the combination of exact AlO4 and CaO6 units gives 1.67 and 2.23 for NO–Al and NO–Ca, respectively. Such small coordination numbers are also found for Mg–O coordination in Mg2SiO4 glass (23), suggesting that this may be a characteristic feature in some oxide glasses with atypical network formers. Table 1 summarizes the effective charges (Qeff) and atomic volumes (Vat) of CA glasses together with those of the corresponding crystalline phases by DFT calculations. The most surprising feature is that Qeff value for Ca (1.4–1.5) is almost comparable to that for Al (1.6). This promotes elemental mixing and is the reason for the unusual atomic coordination of cations around oxygen in 64CaO glass. The bond orders of Al–O and Ca–O bonds (Fig. S4) show the scatter of bond distances (and strengths) in glasses in comparison with crystal structures. Al–O bonds are shorter and have a stronger “bonding” character, but both bond types can be described as prominently ionic based on the effective charges and electronegativity values of the cations (1.5 and 1.0 for Al and Ca, respectively), which differ considerably from that of oxygen (3.5). The high bond strengths of few Ca–O in the C12A7 crystal are due to the “free oxygens” that have adopted asymmetric positions with low coordination in the hollow sites (cages) (10). Furthermore, oxygen is more weakly bound by cations in 64CaO glass, because the bond strength of Al–O is stronger than that of Ca–O.

Table 1.

Atomic charges and volumes of Al, Ca, and O in CA glasses

| Samples | Al |

Ca |

O |

|||

| Qeff, e | Vat, Å3 | Qeff, e | Vat, Å3 | Qeff, e | Vat, Å3 | |

| 50CaO crystal | +1.58 | 61 | +1.49 | 102 | −1.16 | 93 |

| 50CaO glass | +1.59 | 63 | +1.44 | 108 | −1.16 | 95 |

| C12A7 crystal | +1.59 | 65 | +1.46 | 116 | −1.20 | 107 |

| 64CaO glass | +1.55 | 65 | +1.42 | 110 | −1.18 | 100 |

Voronoi prescription of atomic cell/volume is based on geometry, and the corresponding charge is computed from the electron density enclosed inside the cell. The C12A7 crystal comprises a small amount of free oxygens—that is, atoms that are not part of the network and occupy hollow sites—and this is reflected in the individual effective Voronoi charge of –1.32 e and atomic volume of 134 Å3, which differ considerably from the average values. Both glasses have few oxygen atoms with similar volumes.

We calculated bond angle distributions and connectivities of AlOn and CaOx polyhedra to understand the similarities and differences at the correlation length greater than the first coordination distance between 50CaO and 64CaO glasses. It should be emphasized that the application of DFT is imperative in this context because RMC alone tends to produce bond angle distributions that are too broad. As can be seen in Fig. S5, the bond angle distributions of 50CaO glass are very similar to those of 64CaO glass. The O–Al–O bond angle distributions show a peak at ∼107°, reflecting the dominance of AlO4 tetrahedra. The Al–O–Al bond angle distributions show peaks at around 89° and 120°, corresponding to the formation of edge-sharing and corner-sharing of AlOn polyhedra, respectively. This behavior is qualitatively consistent with the results of MD simulation reported by Kang et al. (19). We also calculated the ratio of nonbridging oxygen (NBO) and bridging oxygen (BO) regarding the connectivity of AlOn polyhedra. 50CaO glass shows NBO/BO = 15/85, while 64CaO glass has NBO/BO = 35/65. The contribution of NBO therefore increases at 64CaO, which is in line with the results of MD simulation (19), showing that the AlOn network is not dominant in the 64CaO glass as suggested by McMillan and Piriou (11). On the other hand, the O–Ca–O bond angle distribution shows a wide distribution due to the unusually small average coordination number of ∼5 for Ca–O in both glasses. Furthermore, both the Ca–O–Al and Ca–O–Ca bond angle distributions show a peak at around 92°, suggesting that the connectivities of AlOn–CaOx and CaOx–CaOx are very similar. The connectivities of AlOn–AlOn, AlOn–CaOx, and CaOx–CaOx are shown in Table S2, and indicate similarities between the 50CaO and 64CaO glass data. AlOn polyhedra share oxygen mainly at their corners, while AlOn–CaOx, and CaOx–CaOx show similar behavior in which they have more edge-sharing oxygens. This behavior is consistent with the results of the bond angle distributions for Ca–O–Al and Ca–O–Ca. These results demonstrate that the local structures around Al and Ca do not show significant differences between 50CaO and 64CaO. The most apparent difference between the two CA compositions is the change in O–O coordination arising from the fractional change of OAl3 triclusters.

To reveal the effects of the changes in O–O coordination and OAl3 tricluster fraction on the difference of GFA between 50CaO and 64CaO glasses, ring statistics were calculated using the R.I.N.G.S. code (39) for Al–O, Ca–O, and (Al, Ca)–O rings and are shown in Fig. 4 A–C. Ring statistics of Al–O for 64CaO glass agree well with the results of the MD simulation reported by Thomas et al. (20), while that of 50CaO glass is slightly different from the result of MD simulation reported by Kang et al. (19). The (Al, Ca)–O ring statistics are similar to those of Al–O for both compositions. However, the distribution of Ca–O rings is not uniform, particularly for 50CaO due to the low concentration of CaO. On the other hand, for the 64CaO glass (with high GFA), both Al–O and (Al, Ca)–O show a wide ring size distribution, which can be understood in terms of topological order–disorder according to Gupta and Cooper (40). We found similar behavior in MgO–SiO2 glass (23), where silica-rich composition glass exhibits topological disorder (many large-sized rings with a wide ring size distribution) and has a higher GFA in comparison with silica-poor glass. Therefore, the reduction of OAl3 triclusters gives rise to topological disorder as can be seen in Fig. 4C, where a wide distribution ranging from threefold to 15-fold rings with considerable weights for larger ring sizes is observed for 64CaO glass. This characteristic ring size distribution, and especially the formation of large-sized rings, manifests a crucial intermediate-range structure at the eutectic composition, which exhibits a high viscosity in undercooled liquid, yielding high GFA. Moreover, it has been suggested that the topological disorder in 64CaO glass is a signature of a “stronger” liquid (41) than that of the 50 mol % CaO composition. This scenario can reasonably explain the high GFA of the 64CaO glass without the need for the presence of a traditional network former as proposed in Zachariasen’s original theory (1). Furthermore, this characteristic atomic structure in the 64CaO glass can be understood based on a “cage structure” model, as proposed by Kim et al. (10). Fig. S6 shows an atomic configuration of CA glasses with a cavity analysis (42). Both glasses display a well-defined network structure that enables a variety of ring sizes. There is no significant difference between the two compositions, although the fraction of empty space is slightly smaller for the 64CaO glass.

It is interesting to compare the densities of glasses with those of the crystals. The density of the 50CaO crystal (35) is ∼5% higher than that of the glass, while the density of the C12A7 crystal (36) is almost 9% lower than that of the glass. It is well known that crystalline C12A7 contains free oxygen in cages (10, 36), but there is no free oxygen in the 50CaO crystal (35) and CA glasses. During the crystallization process, the C12A7 glass can release excess oxygen from the small amount of overcoordinated AlO5 and AlO6 polyhedra to form AlO4 tetrahedra and free oxygen. These transformed AlO4 units have more freedom to form an expanded cage structure due to the almost similar coordination numbers of Al and Ca around oxygen. On the other hand, the 50CaO glass cannot form such a cage structure, because the cation coordinations around O are not the same. Furthermore, since both the 50CaO crystal and glass do not have free oxygen, this suggests that the crystallization mechanism of 50CaO glass is different from that of 64CaO. This structural scenario in C12A7 glass can be applied to the C12A7 electride glass synthesized from a strongly reduced high-temperature melt (10), if we presume that the removal of excess O atoms in AlO5 and AlO6 units in the C12A7 melt will result in the formation of more extended cage structures in the electride version of the glass, which can host the solvated electrons.

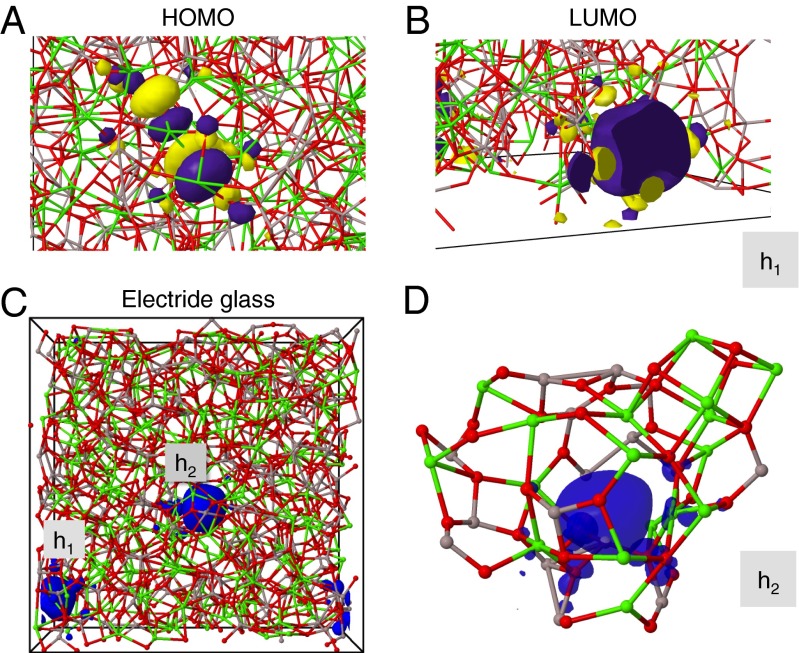

To shed a light on the formation of electride glass reported by Kim et al. (10), the highest occupied (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied (LUMO) single-particle states of electrons were computed for the 64CaO glass by DFT as illustrated in Fig. 5 A and B. The characters of the HOMO and LUMO states are quite different: While the former is located across atoms and bonds (Fig. 5A), the latter is associated with a cavity (cage), making a spin-paired state analogous to an F-center in a vacancy site of crystalline MgO (h1 in Fig. 5B and Fig. S7). The computed HOMO–LUMO gap is 1.71 eV. Since it is well known that DFT simulations at this level underestimate band gaps approximately by a factor of two, this value is consistent with a typical insulating electronic behavior and transparent properties of the glass. Furthermore, our DFT–RMC model suggests that the first three cage-trapped LUMO states appear as impurity states (Fig. S8) below the onset of the conduction band.

Fig. 5.

Close-up visualizations of (A) the HOMO and (B) LUMO single-particle electron states in the 64CaO glass. Both states are spin-degenerate, and h1 labels the cavity (cage) occupied by LUMO. Yellow and magenta stand for different signs of the wave-function nodes. (C) Simulation box and the electron spin-density of the 64CaO glass with one oxygen subtracted at h2—that is, with two additional electrons. The two electrons have the same spin and they occupy separate cavities, h1 (boundary, also shown in B) and h2 (center, location of removed oxygen), which are separated by 12 Å from each other. (D) Cage structure around the spin-density of one electron corresponding to the h2 cavity (close-up from C). Al, gray; Ca, green; O, red.

Following the idea of bipolaron states and conducting electride glass (10), we removed one oxygen atom from the h2 site of Fig. 5B, thus releasing two additional electrons from the Al/Ca cations in the system while keeping the total charge neutral, and then we optimized the structure with several spin configurations by DFT. In the spin-degenerate case, where there is no distinction concerning the “spin” of electrons, these electrons occupy a cavity left by the removed oxygen (marked as h2), yielding a HOMO state similar to that of the LUMO state of the parent system. On the other hand, a removal of the spin-degeneracy (triplet spin configuration) leads to 0.97 eV more energetically favorable electronic configuration, where the two additional electrons have the same spin, and they are located in well-separate cavities (Fig. 5C, h1 and h2). The procedure was repeated for two, three, and four removed oxygens (four, six, and eight additional electrons), and in all cases, the separated (solvated) electrons in individual cages were energetically more preferable than the F-center–like states (two electrons in one cavity). This behavior is similar to the famous case of lithium–ammonia solutions (43). An example of the cage structure around a single electron (spin-density) is presented in Fig. 5D, and it resembles the hollow site in the C12A7 crystal (36). These cases confirm that indeed by removing oxygen from the standard stoichiometry, one can achieve local spin-states in the 64CaO glass. Furthermore, the gradual removal of O increases the number of impurity states within the electronic band gap, which leads to changes in conductivity due to narrower band gap.

In this article, we have investigated the structural basis for glass formation in “network-forming cation-free” CaO–Al2O3 compositions by using a combination of DFT and RMC simulations. Between the 50CaO and 64CaO glasses, we cannot see any significant difference in the oxygen coordination around Al and Ca atoms nor in the connectivity of AlOn and CaOx units. However, we found that the O–O coordination number reduces in the 64CaO glass (eutectic composition) due to the reduction of OAl3 triclusters. This modification enhances topological disorder in the 64CaO glass where O is coordinated by almost the same number of Al and Ca to form a topologically disordered cage structure associated with a wide ring size distribution and considerable fraction of larger rings, which is the signature of the higher GFA of 64CaO glass and the higher viscosity in undercooled stronger liquid (41) at the 64 CaO mol % composition. DFT simulations can explain the origin of characteristic atomic ordering in the eutectic composition in terms of the effective atomic charge and ionic bonding, and support the idea of the formation of solvated electrons (bipolarons, etc.) and tunable conductivity in the electride glass. Furthermore it is also suggested that both C12A7 and CaO64 compositions are better hosts for solvated electrons than the CaO50 composition, because oxygen is more weakly bound by cations in the two former (Ca–O bond is weaker than Al–O and more abundant in CaO-rich composition) (Fig. S4). Thus, it is concluded that the formation of extended cage structures in the C12A7 electride glass, induced by chemical composition and comparable atomic charges for Al and Ca through efficient elemental mixing, is the structural origin of solvated electrons hosted by the cavity sites (cages). Here, large-scale atomic configurations are indispensable for a full understanding, and it is important to reach system sizes that can sustain local inhomogeneity both in terms of atomic and electronic structure. Furthermore, the use of electrostatic levitation technique (44) under highly reducing gases or vacuum can potentially provide a way to synthesize bulk electride glasses from containerless liquids. This approach opens the door to understanding the relationship between structure and physico-chemical properties of glass by a combination of advanced computing and experiments at large-scale facilities. Advancing the understanding of the behavior of fragile liquids will provide crucial information for studying the origin of glass formation and for materials design using unique metastable functional materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. J. Yahiro and Mr. K. Kato for experimental assistance. Discussions with Prof. T. Yamamoto and Dr. K. Fukumi are gratefully appreciated. The synchrotron radiation experiment was carried out with the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (Proposals 2006B1461 and 2008B1166), and the DFT calculations were carried out on the Juropa (Xeon 5570) computers in the Forschungszentrum Jülich and Cray XT4/XT5 computers in CSC the IT Center for Science Ltd., Finland. This work was supported by the US Department of Energy at the Advanced Photon Source under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357 and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (24350111) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. S.K. and J.A. were supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency and the Academy of Finland via the Strategic Japanese-Finland Cooperative Program on “Functional Materials” 2009–2012. J.A. acknowledges further support from the Academy of Finland through its Centres of Excellence Program (Project 251748).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1300908110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zachariasen WH. The atomic arrangement in glass. J Am Chem Soc. 1932;54(10):3841–3851. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun K-H. Fundamental condition of glass formation. J Am Ceram Soc. 1947;30(9):277–281. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung WJ, Heo J. Energy transfer process for the blue up-conversion in calcium aluminate glasses doped with Tm3+ and Nd3+ J Am Ceram Soc. 2001;84(2):348–352. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hafner HC, Kreidl NJ, Weidel RA. Optical and physical properties of some calcium aluminate glasses. J Am Ceram Soc. 1958;41(8):315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onoda GY, Brown SD. Low-silica glasses based on calcium aluminates. J Am Ceram Soc. 1970;53(6):311–316. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davy JR. Development of calcium aluminate glasses for use in the infrared spectrum to 5μm. Glass Technol. 1978;19(2):32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumbaugh WH. Infrared transmitting glasses. Opt Eng. 1985;24(2):257–262. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lines ME, et al. Calcium aluminate glasses as potential ultralow-loss optical materials at 1.5-1.9 μm. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1989;107(2–3):251–260. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards PP. Chemistry. Electrons in cement. Science. 2011;333(6038):49–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1207837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SW, Shimoyama T, Hosono H. Solvated electrons in high-temperature melts and glasses of the room-temperature stable electride [Ca₂₄Al₂₈O₆₄]⁴⁺·4e⁻. Science. 2011;333(6038):71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1204394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMillan P, Piriou B. Raman spectroscopy of calcium aluminate glasses and crystals. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1983;55(2):221–242. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMillan PF, et al. A structural investigation of CaO–Al2O3 glasses via 27Al MAS-NMR. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1996;195(3):261–271. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iuga D, et al. NMR heteronuclear correlation between quadrupolar nuclei in solids. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(33):11540–11541. doi: 10.1021/ja052452n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannon AC, Parker JM. The structure of aluminate glasses by neutron diffraction. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2000;274(1–3):102–109. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cormier L, Neuville DR, Calas G. Structure and properties of low-silica calcium aluminosilicate glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2000;274(1–3):110–114. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mei Q, Benmore CJ, Siewenie J, Weber JKR, Wilding M. Diffraction study of calcium aluminate glasses and melts: I. High energy x-ray and neutron diffraction on glasses around the eutectic composition. J Phys: Condens Matter. 2008;20(24):245106-1–245106-8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mei Q, et al. Diffraction study of calcium aluminate glasses and melts: II. High energy x-ray and neutron diffraction on melts. J Phys Condens Matter. 2008;20(24):245107-1–245107-7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drewitt JWE, et al. The structure of liquid calcium aluminates as investigated using neutron and high energy x-ray diffraction in combination with molecular dynamics simulation methods. J Phys Condens Matter. 2011;23(15):155101––155114. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/23/15/155101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang ET, Lee SJ, Hannon AC. Molecular dynamics simulations of calcium aluminate glasses. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2006;352(8):725–736. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas BWM, Mead RN, Mountjoy G. A molecular dynamics study of the atomic structure of (CaO)x(Al2O3)1−x glass with x = 0.625 close to the eutectic. J Phys Condens Matter. 2006;18(19):4697–4708. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ikeda T, Boero M, Terakura K. Hydration properties of magnesium and calcium ions from constrained first principles molecular dynamics. J Chem Phys. 2007;127(7):074503–074508. doi: 10.1063/1.2768063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGreevy RA, Pusztai L. Reverse Monte Carlo simulation: A new technique for the determination of disordered structures. Mol Simul. 1988;1(6):359–367. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohara S, et al. Relationship between topological order and glass forming ability in densely packed enstatite and forsterite composition glasses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(36):14780–14785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104692108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benmore CJ, et al. A neutron and x-ray diffraction study of calcium aluminate glasses. J Phys Condens Matter. 2003;15(31):S2413–S2423. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boero M. Excess electron in water at different thermodynamic conditions. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111(49):12248–12256. doi: 10.1021/jp074356+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen RE, Glover WJ, Schwartz BJ. Does the hydrated electron occupy a cavity? Science. 2010;329(5987):65–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1189588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uhlig F, Marsalek O, Jungwirth P. Unraveling the complex nature of the hydrated electron. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3(20):3071–3075. doi: 10.1021/jz301449f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kohara S, et al. Structural studies of disordered materials using high-energy x-ray diffraction from ambient to extreme conditions. J Phys Condens Matter. 2007;19(50):506101-1–506101-15. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gereben O, Jóvári P, Temleitner L, Pusztai L. A new version of the RMC++ Reverse Monte Carlo programme, aimed at investigating the structure of covalent glasses. J Optoelectron Adv Mater. 2007;9(10):3021–3027. [Google Scholar]

- 30.CP2K Developers Group 2000–2011. http://cp2k.berlios.de.

- 31.VandeVondele J, et al. QUICKSTEP: Fast and accurate density functional calculations using a mixed Gaussian and plane waves approach. Comput Phys Commun. 2005;167(2):103–128. [Google Scholar]

- 32.VandeVondele J, Hutter J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J Chem Phys. 2007;127(11):114105–114109. doi: 10.1063/1.2770708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goedecker S, Teter M, Hutter J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys Rev B. 1996;54(3):1703–1710. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.54.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys Rev Lett. 1996;77(18):3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoerkner W, Mueller-Buschbaum H. Zur Kristallstruktur von CaAl2O4. J Inorg Nucl Chem. 1976;38(5):983–984. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buessem W, Eitel A. Die Struktur des Pentacalciumtrialuminats. Kristallphysik Kristallchemie. 1936;95:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akola J, Jones RO. Density functional calculations of ATP systems. 1. Crystalline ATP hydrates and related molecules. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110(15):8110–8120. doi: 10.1021/jp054920l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drewitt JWE, et al. Structural transformations on vitrification in the fragile glass-forming system CaAl2O4. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109(23):235501–235505. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.235501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Roux S, Jund P. Ring statistics analysis of topological networks: New approach and application to amorphous GeS2 and SiO2 systems. Comput Mater Sci. 2010;49(1):70–83. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta PK, Cooper AR. Topologically disordered networks of rigid polytopes. J Non-Cryst Solids. 1990;123(1–3):14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Angell CA. Formation of glasses from liquids and biopolymers. Science. 1995;267(5206):1924–1935. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5206.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akola J, Jones RO. Structural phase transitions on the nanoscale: The crucial pattern in the phase-change materials Ge2Sb2Te5 and GeTe. Phys Rev B. 2007;76(23):235201-1–235201-10. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zurek E, Edwards PP, Hoffmann R. A molecular perspective on lithium-ammonia solutions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48(44):8198–8232. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhim W-K, et al. An electrostatic levitator for high-temperature containerless materials processing in 1-g. Rev Sci Instrum. 1993;64(10):2961–2970. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cormier L, Neuville DR. Ca and Na environments in Na2O–CaO–Al2O3–SiO2 glasses: Influence of cation mixing and cation-network interactions. Chem Geol. 2004;213(1–3):103–113. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto T. Assignment of pre-edge peaks in K-edge x-ray absorption spectra of 3d transition metal compounds: electric dipole or quadrupole? X-ray Spectrom. 2008;37(6):572–584. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fulton JL, Heald SM, Badyal YS, Simonson JM. Understanding the effects of concentration on the solvation structure of Ca2+ in aqueous solution. I: The perspective on local structure from EXAFS and XANES. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107(23):4688–4696. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.