In utero, fetal lung epithelial cells actively secrete chloride (Cl−) ions into the lung airspaces. Cl− ions enter the basolateral membranes through Na+/K+/2Cl− (NKCC) transporters (1), down an electrochemical gradient generated by the basolateral Na+/K+/ATPase, and exit through apical anion channels, including the cAMP- activated cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) (2). Na+ ions follow passively through the paracellular junctions to preserve electroneutrality. The vectorial transport of NaCl generates an oncotic pressure, which drives fetal fluid secretion into the airway lumen. Shortly before birth, Cl− secretion diminishes and active Na+ transport begins: Na+ ions enter lung epithelial cells through amiloride-sensitive Na+ channels (ENaC) and are extruded across the basolateral membranes by the Na+/K+/ATPase (3, 4). This process is critical for the reabsorption of fetal lung fluid and the establishment of gas exchange. In the adult lung active Na+ reabsorption limits the degree of alveolar edema in hyperoxic lung injury (5) and in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (6, 7).

In PNAS, Solymosi et al. (8) show that an acute increase of left atrial pressure in isolated perfused rat lungs decreases amiloride-sensitive Na+ reabsorption across alveolar epithelial cells and stimulates Na+ and Cl− uptake through the basolateral NKCC transporter. Decreased Na+ entry through ENaC in epithelial cells also resulted in hyperpolarization of their apical membranes, providing the driving force for Cl− secretion and fluid accumulation in the alveolar spaces. Previous studies (9, 10) documented that an acute increase of pulmonary or left atrial pressures decreased active Na+ reabsorption across the alveolar epithelium, which contributed to pulmonary edema. Thus, the study by Solymosi et al. (8) offers fresh insight into the mechanism of edema formation following an acute increase of left atrial pressure. In contrast to the fetal fluid, which is essential to lung development, accumulation of alveolar fluid in the adult lung compromises gas exchange. Solymosi et al. propose that the beneficial effects of furosemide (a NKCC blocker) administration in patients with congestive heart failure, secondary to an increase of left atrial pressure may be, at least in part, because of the inhibition of Cl− secretion across the alveolar epithelium.

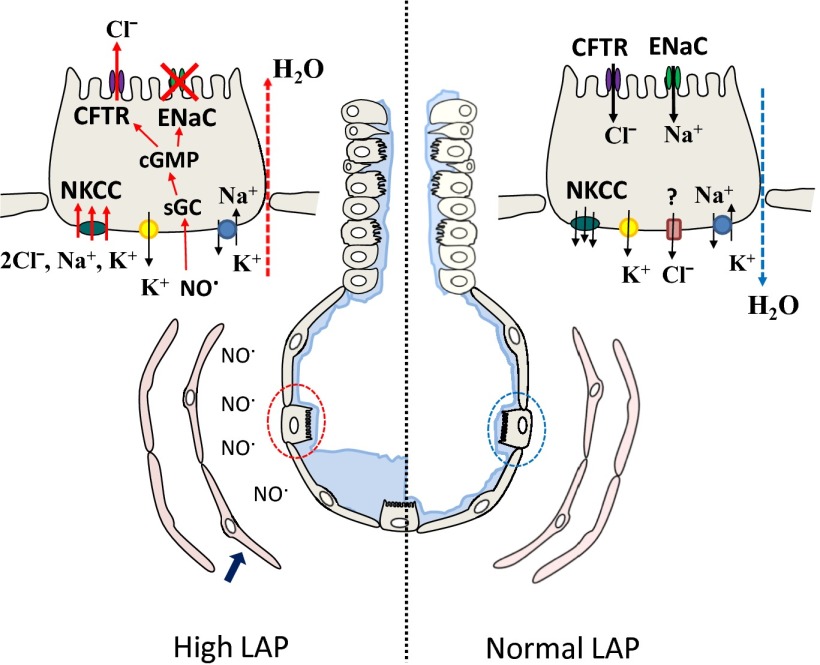

There has been considerable interest in identifying the mechanisms by which Cl− crosses adult alveolar epithelial cells. It was thought that Cl− moved passively from the alveolar into the interstitial space through the paracellular junctions to preserve electroneutrality. However, Wolk et al. (11) showed that alveolar instillation of a CFTR inhibitor decreased alveolar fluid clearance (AFC) by about 20%, suggesting the presence of transcellular Cl− movement through the CFTR. Solymosi et al. (8) also report that inhibitors of the CFTR decreased AFC by 25–30%. Previously, Fang et al. (12) showed that ΔF508 mice, the most common CFTR mutation, had normal levels of Na+-dependent AFC, but in contrast to wild-type mice, did not increase their AFC following instillation of β-agonists or forskolin. Cl− exits alveolar epithelial cells either through the NKCC transporter or through other nonidentified pathways (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Transcellular Na+ and Cl− movement across alveolar epithelial cells. Schematic representation of a terminal bronchiole and alveolus, consisting of ATII (dotted circles) and ATI cells. Solid blue arrow points to endothelial cells. Ion transport across an alveolar epithelial cell under normal or increased left atrial pressures (LAP) are shown. Cl− exit ATII cells either through the NKCC or through nonidentified Cl− channels. Sequence of events leading to Cl− secretion and decreased Na+ absorption when LAP is increased is discussed in the text. sGC, soluble guanalyl cyclase.

Chloride secretion has been demonstrated in vivo, in air-filled (13) and fluid-filled lungs, in the presence of a Cl− secretory gradient and cAMP activation (14). Influenza-infected mice developed decreased Na+ reabsorption and increased Cl− secretion across their alveolar epithelium in vivo (11). Cl− secretion has also been shown in confluent monolayers of rat and human alveolar epithelial type II (ATII) cells in the presence of amiloride (to block ENaC) and forskolin (to activate the CFTR) (15, 16). Finally, studies of small airways using a miniature Ussing chamber system showed a switch from Cl− absorption to secretion through CFTR when Na+ transport was inhibited by amiloride (17). Thus, there is clear evidence for the transcellular absorption of Cl− across adult alveolar epithelial cells through the CFTR and other anion channels under baseline conditions. In addition, when Na+ transport is compromised and a favorable Cl− gradient is established, Cl− secretion may occur.

In PNAS, Solymosi et al. (8). (Fig. 1) propose that an acute increase of left atrial pressure activates endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase, resulting in increased levels of NO, which inhibits ENaC activity via cGMP-dependent mechanisms. Decreased influx of Na+ ions across alveolar epithelial cells resulted in hyperpolarization of their apical cell membranes (18), increased Na+ and Cl− influx through the basolateral NKCC, and Cl− secretion through apical CFTR. Previously, NO has been shown to decrease ENaC single channel activity in rat ATII cells (19) and vectorial Na+ transport across confluent monolayers of rat ATII cells (20) via cGMP-dependent and independent mechanisms. Furthermore, intratracheal instillation of a NO donor decreased amiloride-sensitive AFC in rabbit lungs (21). Solymosi et al. (8) also show that a PKGII inhibitor prevents Cl− secretion following an increase in left atrial pressure. Previous studies have shown that small amounts of NO increase cAMP-activated Cl− secretion across Calu-3 (22) and amiloride-treated ATII cells by phosphorylating CFTR via a PKGII-dependent mechanism (15).

The unique findings of Solymosi et al. (8) suggest that endothelial NOS, as well as alveolar epithelial CFTR and NKCC, may be putative therapeutic targets to diminish pulmonary edema following an acute increase in left atrial pressure. Isolated perfused lungs of CFTR (−/−) mice did not develop pulmonary edema when subjected to increased left atrial pressure. Furthermore, aerosolized furosemide prevented the increase in wet/dry weight ratios (an index of pulmonary edema) in rats with an acute occlusion of the left descending coronary artery. One may then wonder if these results can be extrapolated in patients with congestive heart failure and noncardiogenic edema. Patients with cardiogenic edema have higher levels of nitrate and nitrite (the by-products of NO) in their alveolar edema fluid and plasma (23). Approximately two-thirds of patients with severe hydrostatic pulmonary edema exhibit impaired AFC (24). However, mice with chronic heart failure had normal levels of alveolar fluid clearance and basal levels of NO (10). It is possible that in mice with congestive heart failure, decreased endothelial NO synthase activity and NO levels may be an important compensatory mechanism, limiting the extent of lung edema formation. Thus, the study by Solymosi et al. (8) clearly enhances our understanding of the mechanisms leading to the formation of pulmonary edema following an acute increase in left atria pressure and elucidates an important unique mechanism for the therapeutic potential of furosemide.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge funding from the following grants: 5 R01 HL031197-27 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) and 5U01ES015676 (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the NIH CounterACT Program).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page E2308.

References

- 1.Gillie DJ, Pace AJ, Coakley RJ, Koller BH, Barker PM. Liquid and ion transport by fetal airway and lung epithelia of mice deficient in sodium-potassium-2-chloride transporter. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25(1):14–20. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.1.4500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker PM, Brigman KK, Paradiso AM, Boucher RC, Gatzy JT. Cl- secretion by trachea of CFTR (+/-) and (-/-) fetal mouse. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13(3):307–313. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.3.7544595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eaton DC, Helms MN, Koval M, Bao HF, Jain L. The contribution of epithelial sodium channels to alveolar function in health and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:403–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matalon S, Lazrak A, Jain L, Eaton DC. Invited review: Biophysical properties of sodium channels in lung alveolar epithelial cells. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93(5):1852–1859. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01241.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue G, Matalon S. Mechanisms and sequelae of increased alveolar fluid clearance in hyperoxic rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;272(3 Pt 1):L407–L412. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.3.L407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthay MA, Wiener-Kronish JP. Intact epithelial barrier function is critical for the resolution of alveolar edema in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142(6 Pt 1):1250–1257. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solymosi EA, et al. Chloride transport-driven alveolar fluid secretion is a major contributor to cardiogenic lung edema. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E2308–E2316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216382110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saldías FJ, et al. Alveolar fluid reabsorption is impaired by increased left atrial pressures in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281(3):L591–L597. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaestle SM, et al. Nitric oxide-dependent inhibition of alveolar fluid clearance in hydrostatic lung edema. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293(4):L859–L869. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00008.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolk KE, et al. Influenza A virus inhibits alveolar fluid clearance in BALB/c mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(9):969–976. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-455OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang X, et al. Novel role for CFTR in fluid absorption from the distal airspaces of the lung. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119(2):199–207. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindert J, Perlman CE, Parthasarathi K, Bhattacharya J. Chloride-dependent secretion of alveolar wall liquid determined by optical-sectioning microscopy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36(6):688–696. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0347OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen VG, Duvall MD, Baird MS, Matalon S. cAMP activation of chloride and fluid secretion across the rabbit alveolar epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(6 Pt 1):L1127–L1133. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L, et al. DETANO and nitrated lipids increase chloride secretion across lung airway cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39(2):150–162. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0005OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bove PF, et al. Human alveolar type II cells secrete and absorb liquid in response to local nucleotide signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(45):34939–34949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shamsuddin AK, Quinton PM. Surface fluid absorption and secretion in small airways. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 15):3561–3574. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazrak A, Matalon S. cAMP-induced changes of apical membrane potentials of confluent H441 monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285(2):L443–L450. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00412.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain L, Chen XJ, Brown LA, Eaton DC. Nitric oxide inhibits lung sodium transport through a cGMP-mediated inhibition of epithelial cation channels. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(4 Pt 1):L475–L484. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.4.L475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo Y, DuVall MD, Crow JP, Matalon S. Nitric oxide inhibits Na+ absorption across cultured alveolar type II monolayers. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(3 Pt 1):L369–L377. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.3.L369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen VG, Baird MS, Chen L, Matalon S. DETANONOate, a nitric oxide donor, decreases amiloride-sensitive alveolar fluid clearance in rabbits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(4 Pt 1):1154–1160. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9907033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, et al. Mechanisms of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activation by S-nitrosoglutathione. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(14):9190–9199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu S, Ware LB, Geiser T, Matthay MA, Matalon S. Increased levels of nitrate and surfactant protein a nitration in the pulmonary edema fluid of patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(1):166–172. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verghese GM, Ware LB, Matthay BA, Matthay MA. Alveolar epithelial fluid transport and the resolution of clinically severe hydrostatic pulmonary edema. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87(4):1301–1312. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.4.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]