Abstract

Background

Only limited data on the prevalence of iron deficiency (ID) and its correlation with clinical parameters are available in cancer. ID frequently contributes to the pathogenesis of anemia in patients with cancer and may lead to several symptoms such as impaired physical function, weakness and fatigue.

Patients and methods

Parameters of iron status and clinical parameters were evaluated in 1528 patients with cancer who presented consecutively within a four-month period at our center. One thousand fifty-three patients had solid tumors and 475 hematological malignancies.

Results

ID [transferrin saturation (TSAT) < 20%] was noted in 645 (42.6%) of the 1513 patients with TSAT tests available and 500 (33.0%) were anemic. ID rates were highest in pancreatic (63.2%), colorectal (51.9%) and lung cancers (50.7%). Of the 409 iron-deficient patients in whom serum ferritin levels were available additionally to TSAT, 335 (81.9%) presented with functional ID (FID) (TSAT < 20%, serum ferritin ≥30 ng/ml) and 74 (18.1%) with absolute ID. In patients with solid tumors, prevalence of ID correlated with cancer stage at diagnosis (P = 0.001), disease status (P = 0.001) and ECOG performance status (P = 0.005).

Conclusions

ID was frequently noted in cancer and was associated with advanced disease, close proximity to cancer therapy, and poor performance status in patients with solid tumors.

Keywords: absolute iron deficiency, cancer-related anemia, chemotherapy-induced anemia, functional iron deficiency, iron deficiency anemia, iron deficiency

introduction

Anemia is a frequent complication of cancer and cancer therapy [1], but little is known about the prevalence of iron deficiency (ID) in cancer patients and data from clinical studies are scarce. In fact, only few reports are available [2–6], of which some have been presented at meetings only [5, 6], and most of them have not used the required spectrum of laboratory tests for detecting ID in all patients investigated.

Impaired iron homeostasis associated with chronic disease, chronic blood loss and nutritional deficiencies (e.g. cancer-induced anorexia) are the main causes of ID in cancer patients [2]. ID can present as absolute ID (AID; depleted iron stores, serum ferritin <30 ng/ml) [7] or functional ID (FID) that is characterized by iron sequestration and thus, a lack of biologically available iron [transferrin saturation (TSAT) <20%], despite normal iron stores [8]. Several different markers and cut-offs have been proposed and used for monitoring of iron status and for diagnosis of ID [9, 10].

ID can be associated with a variety of symptoms such as impaired physical function and fatigue [11, 12]. Repletion of iron in iron-deficient, but non-anemic women improved physical performance [11] and fatigue scores [12, 13]. Similar improvements were noted with intravenous iron substitution in non-anemic patients with chronic heart failure [14]. In iron-deficient cancer patients with chemotherapy-related anemia (Hb < 10.5 g/dl), addition of intravenous iron to treatment with an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent was associated with substantially better outcomes in Hb levels, energy, activity and overall quality of life [15]. The improved erythropoietic response was confirmed in a meta-analysis summarizing the results of eight similar trials [16].

In this study, we assessed the prevalence of ID in a large unselected population of patients with different types of solid and hematological malignancies and evaluated interdependencies between ID and stage, disease status, proximity of treatment of the underlying cancer, as well as possible correlations with performance status.

patients and methods

One thousand five hundred and twenty-eight cancer patients presenting sequentially between 1 October 2009 and 20 January 2010, in the outpatient department or admitted to the inpatient wards of the Center for Oncology, Hematology and Palliative Care, Wilhelminenspital, Vienna, Austria, have been enrolled. Patients were at different stages of their disease or may not have had an established diagnosis at the time of testing. Evaluation of patients included assessment of age, gender, tumor type, cancer stage at initial diagnosis, disease status, performance status, Hb values and iron status and whether patients had received anticancer therapy and in case they did, the time that elapsed since administration of last tumor treatment also was recorded. TSAT, serum ferritin, serum iron, C-reactive protein (CRP) and complete blood count were determined. In patients with multiple testing during the study period, only the first sample taken was included in the analysis.

definition of ID, anemia and disease status

Commonly used definitions for ID and anemia were applied [8–10]. ID was defined as TSAT < 20% and was further classified as AID or FID if serum ferritin levels were available in addition to TSAT values. AID was defined as TSAT < 20% and serum ferritin <30 ng/ml. FID was defined as TSAT <20% and serum ferritin ≥30 ng/ml. As a standardized definition of anemia, Hb ≤ 12 g/dl was used.

For disease status, patients were categorized as ‘complete response’ according to standard response criteria, or ‘persistent disease’ if their initial tumor was either not yet treated or treatment did not result in complete remission, and ‘progressive’ in case RECIST criteria or other appropriate criteria indicated progressive disease. Cancers were staged at initial diagnosis and categorized into stage I and II, III and IV.

statistical methods

The results are mainly illustrated by descriptive statistics. χ2 and Fisher's exact tests were used for comparison of frequencies.

results

patient characteristics

Of the 1528 patients, 1053 (68.9%) presented with solid tumors and 475 (31.1%) with hematological malignancies. Table 1 shows demographic patient data, distribution of tumor types, stage at initial diagnosis and other relevant information.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | Patients with solid tumors | Patients with hematological malignancies |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 1053 | 475 |

| Age, mean years (range) | 65.0 (22.5–96.8) | 64.0 (20.0–89.9) |

| Male/female (%) | 424 (40.3)/629 (59.7) | 222 (46.7)/253 (53.3) |

| ECOG status, number of patients (%) | ||

| 0 | 782 (74.3) | 398 (83.8) |

| 1 | 156 (14.8) | 49 (10.3) |

| 2 | 73 (6.9) | 19 (4.0) |

| 3 | 19 (1.8) | 5 (1.1) |

| 4 | 16 (1.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing data | 7 (0.7) | 3 (0.6) |

| Tumor type, n (%) | Colorectal cancer 366 (34.8) | Lymphoma 163 (34.3) |

| Breast cancer 298 (28.3) | Myeloma 163 (34.3) | |

| Lung cancer 76 (7.2) | MGUS* 82 (17.3) | |

| Genitourinary cancer 66 (6.3) | Leukemia 67 (14.1) | |

| GI/Esophageal cancer 51 (4.8) | ||

| Pancreatic cancer 38 (3.6) | ||

| Testicular cancer 31 (2.9) | ||

| Gynecological cancer 29 (2.8) | ||

| Other 98 (9.3) | ||

| Stage at initial diagnosis, number of patients (%) | ||

| Stage I–II | 316 (30.0) | 104 (21.9) |

| Stage III | 168 (16) | 141 (29.7) |

| Stage IV | 502 (47.7) | 79 (16.6) |

| Not classifiable* | 9 (0.9)* | 111 (23.4)** |

| Missing/others | 58 (5.5) | 40 (8.4) |

| Disease status, n (%) | ||

| Complete response | 571 (54.2) | 254 (53.5) |

| Persistent disease | 435 (41.3) | 202 (42.5) |

| Progressive disease | 28 (2.7) | 10 (2.1) |

| Missing data | 19 (1.8) | 9 (1.9) |

| Anticancer treatment before evaluation, number of patients (%) | ||

| No treatment | 219 (20.8) | 177 (37.3) |

| Treatment 0–4 weeks*** prior | 365 (34.7) | 133 (28.0) |

| Treatment 5–12 weeks prior | 32 (3.0) | 8 (1.7) |

| Treatment > 13 weeks prior | 419 (39.8) | 148 (31.2) |

| Missing data | 18 (1.7) | 9 (1.9) |

| TSAT, mean (n tested) | 21.9% (1044) | 25.3% (469) |

| Serum ferritin, mean (n tested) | 422.3 ng/ml (414) | 284.8 ng/ml (466) |

| Hb, mean (n tested) | 12.6 g/dl (1043) | 12.6 g/dl (466) |

| CRP, mean (n tested) | 35.0 mg/l (449) | 10.5 mg/l (469) |

*Pre-malignant (DCIS) *MGUS and leukemias other than CLL, ***weeks.

TSAT and Hb were assessed in nearly all patients (1513 and 1509, respectively), while serum ferritin levels were available for an 880 patients only. Overall, 42.6% of patients were iron deficient (TSAT < 20%) and 33.3% were anemic (Hb ≤ 12 g/dl). The respective prevalence was 45.9% and 33% in patients with solid tumors and 35.4% and 33.9% in patients with hematological malignancies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Iron parameters and Hb across tumor types in patients with available TSAT (n = 1513), Hb (n = 1509) and ferritin (n = 880)

| Parameters | Solid tumors |

Hematological malignancies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Colorectal | Breast | Lung | Other | All | |

| TSAT, n (%)a | 1044 | 360 | 298 | 75 | 311 | 469 |

| <20% | 479 (45.9) | 187 (51.9) | 118 (39.6) | 38 (50.7) | 136 (43.7) | 166 (35.4) |

| 20–<30% | 375 (35.9) | 111 (30.8) | 126 (42.3) | 18 (24.0) | 120 (38.6) | 180 (38.4) |

| ≥30% | 190 (18.2) | 62 (17.2) | 54 (18.1) | 19 (25.3) | 55 (17.7) | 123 (26.2) |

| Ferritin, n (%)b | 414 | 143 | 62 | 48 | 161 | 466 |

| 0–30 ng/ml | 47 (11.4) | 25 (17.5) | 8 (12.9) | 3 (6.3) | 11 (6.8) | 48 (10.3) |

| >30–100 ng/ml | 102 (24.6) | 48 (33.6) | 19 (30.6) | 6 (12.5) | 29 (18.0) | 159 (34.1) |

| >100 ng/ml | 265 (64.0) | 70 (48.9) | 35 (56.5) | 39 (81.2) | 121 (75.2) | 259 (55.6) |

| Hb, n (%)c | 1043 | 353 | 294 | 75 | 321 | 466 |

| <10 g/dl | 102 (9.8) | 34 (9.6) | 17 (5.8) | 13 (17.3) | 38 (11.8) | 49 (10.5) |

| 10–12 g/dl | 242 (23.2) | 88 (24.9) | 61 (20.7) | 18 (24) | 75 (23.4) | 107 (23.0) |

| >12 g/dl | 699 (67.0) | 231 (65.4) | 216 (73.5) | 44 (58.7) | 208 (64.8) | 310 (66.5) |

aTSAT was available in 1513.

bFerritin in 880.

cHb in 1509 patients only.

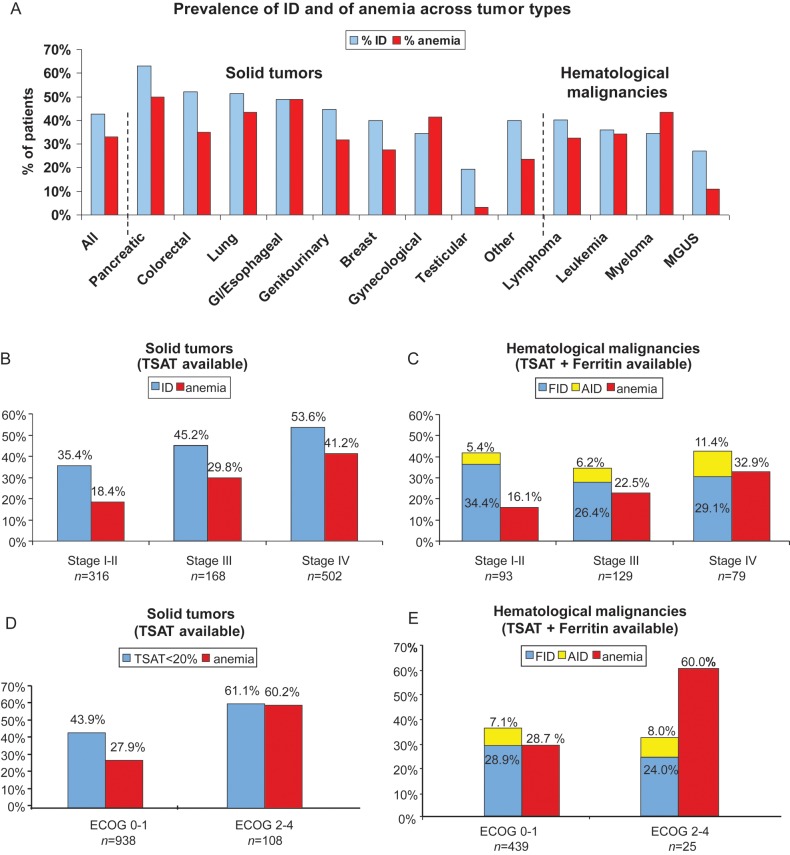

Across most tumor types evaluated, a high prevalence of ID and anemia was noted (Figure 1A). ID rates were highest in pancreatic (63.2%), colorectal (52.2%) and lung cancer (51.3%). Prevalence of ID correlated with the prevalence of anemia in most solid tumor types. Anemia was detected in 50.4% of ID patients with solid tumors and 43.7% of ID patients with hematological malignancies. Almost one-third of anemic patients had moderate-to-severe anemia (Hb values <10 g/dl) (29.7% and 31.2% of anemic patients with solid tumors and hematological malignancies, respectively).

Figure 1.

(A) Prevalence of ID and anemia across different tumor types in patients with available TSAT and Hb (n = 1509). (B) Prevalence of ID and anemia in relation to stage in patients with solid tumors and (C) in patients with hematological malignancies. (D) Correlation of ID and anemia with ECOG performance status in patients with solid tumors and (E) in those with hematological malignancies.

In patients with solid tumors, higher mean ferritin levels were noted (422.3 ng/ml) compared with patients with hematological malignancies (284.8 ng/ml) (P < 0.001). Similarly, the mean CRP concentrations were higher in patients with solid tumors than in those with hematological malignancies (35.0 mg/l versus 10.5 mg/l; P < 0.001). Among the 409 iron-deficient patients with TSAT and serum ferritin levels available, the majority (81.9%) presented with FID, while AID was less common (18.1%).

tumor stage, ID and anemia

Statistical analysis revealed a significant correlation between ID and tumor stage in the total cohort of patients (P < 0.001). Similar correlations were found between anemia and tumor stage (P < 0.001). In patients with solid tumors, a significant correlation between ID and stage and anemia was found (P < 0.0001 and P < 0.0001, respectively). Prevalence of ID increased from 35.4% in stage I–II to 45.2% in stage III and 53.6% in stage IV patients, the corresponding figures for anemia were 18.4%, 29.8% and 41.2%, respectively (Figure 1B). In patients with hematological malignancies, ferritin levels were available in 98.0% of patients. Therefore, prevalence data for both AID and FID are provided in this patient cohort (Figure 1C). Notably, FID was comparably prevalent (26.4%–34.4%) across all stages of hematological malignancies, whereas AID showed a trend for higher prevalence in stage IV disease (stage I–II: 5.4%, stage III: 6.2%, stage IV: 11.4%, P = 0.20). For anemia, a significant correlation between stage and prevalence was noted (stage I–II: 16.1%, stage III: 22.5%, stage IV: 32.9%; P < 0.04).

anticancer treatment, ID and anemia

Patients were categorized into three groups: (i) not having received anticancer therapy, (ii) having received their most recent anticancer treatment within 12 weeks or (iii) >12 weeks before testing. The prevalence of both ID and anemia was higher in patients having received their last anticancer therapy ≤12 weeks compared with those having been treated with >12 weeks from baseline (Table 3). This was true for the total group of patients (ID: 48.1 versus 36.3%, P < 0.001, anemia: 50.4 versus 18.7%; P < 0.001) and for patients with solid tumors (ID: 51.6% versus 37.7%; P < 0.001, anemia: 48.6 versus 17.2%; P < 0.001), while for patients with hematological malignancies the same pattern was noted for anemia only (ID: 38.3 versus 32.4%; P = 0.92, anemia: 55.3 versus 23.0%; P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Prevalence of ID and anemia by proximity to anticancer treatment and by disease status in patients with available TSAT and Hb (n = 1509)

|

disease status, ID and anemia

Patients with persistent or progressive disease at the time of evaluation were more frequently iron deficient and anemic than patients in complete remission (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 3). Of patients with solid tumors, 56.8% with persistent and 57.1% with progressive disease were iron deficient, and 47.6% and 39.3%, respectively, were anemic compared with 36.4% and 20.7%, respectively, of patients in complete remission. The respective figures for ID in patients with hematological malignancies were 38.1% for persistent and 40.0% for progressive disease, and for anemia 48.5% and 50.0%; respectively, while in the CR patients a slightly lower prevalence of ID (31.9%) and a significantly lower prevalence of anemia (19.3%) were noted (P < 0.001). Disease status significantly correlated with iron status in patients with solid tumors (P < 0.001), but not in hematological malignancies (P = 0.172) whereas highly significant correlations between disease status and anemia could be observed in both solid tumor and hematological malignancy patients (P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively).

ECOG performance status, ID and anemia

Both ID and anemia significantly correlated with poor ECOG performance status (P = 0.005 and P = 0.001, respectively) Patients with solid tumors and poor performance status (ECOG 2–4) presented more frequently with ID (61.1%) and anemia (60.2%) than patients with good performance status (ECOG 0–1; ID: 43.9%; anemia: 27.9%) (Figure 1D). In patients with hematological tumors (Figure 1E), a similar pattern was observed for anemia (P = 0.001), but not for ID (P = 0.89). However, the low number of hematological patients with poor performance status (n = 25) limits the validity of the latter finding.

discussion

Our results reveal a high prevalence of ID across different tumor types. ID correlated with anemia, cancer stage, anticancer therapy within ≤12 weeks from baseline, persistent and progressive disease and poor performance status in patients with solid tumors, while in hematological malignancies significant correlations with ID were not found. The restriction of the correlations between ID and parameters reflecting more advanced disease to patients with solid tumors only may be due to higher levels of inflammatory cytokines as manifested by higher CRP levels, with more advanced cancer. In hematological malignancies, a possible correlation might have remained unrecognized because of the limited number of patients.

Iron status was mainly assessed by TSAT which is only modestly influenced by inflammation. Ferritin, in contrast, belongs to the group of acute phase proteins [9, 10] and often does not reflect iron stores [9] in cancer, due to its interdependence with inflammatory reactions [17]. Actually, the mean CRP levels were significantly higher in patients with solid tumors (35 mg/l; normal <5.0 mg/l) than in patients with hematological malignancies (10.5 mg/l). If only ferritin (with a cut-off value of <30 ng/ml) would have been used for identification of ID, the majority of iron-deficient patients presenting with FID only would have remained undiagnosed. This highlights the importance of using TSAT as an appropriate biomarker for assessing iron availability in cancer patients, but comparison with other reports shows that TSAT is often not assessed [18–20].

The variation in the prevalence of ID in patients with different tumor types (Figure 1A) is noteworthy. The high prevalence in pancreatic, and particularly, in colorectal cancers seems to be the consequence of a combination of blood loss and inflammatory response, while in lung cancer, both the disease itself and the sequels of toxic chemotherapy, which likely induces a strong inflammatory response, may account for ID. The increased prevalence of ID in patients with persistent or progressive tumors and in those with recent anticancer therapy supports the aforementioned concept of a fundamental interplay between malignant cell growth, cancer therapy, the immune system and iron homeostasis.

Previously, iron status in cancer patients has not extensively been addressed; hence, only limited information is available for comparison with our data. Kuvibidila et al. [3] reported lower mean TSAT and higher total iron binding capacity in 34 men with prostate cancer compared with controls; 31.6% of patients had TSAT <16% compared with 8.6% of controls. Robertson and Hutchinson [18] described ID in 9% of anemic cancer patients and found suggestive, but inconclusive evidence of ID in a further 41% of patients. Beale et al. showed evidence of ID in 60% of 130 patients with colorectal cancer with reduced TSAT levels in 42.3% and decreased ferritin concentrations in 13.8%. Remarkably, 69% of patients with low TSAT (<16%) were also anemic [4]. This figure compares well with the 50.4% prevalence of anemia found among iron-deficient solid tumor patients in our study, while in iron-deficient patients with hematological cancers a lower prevalence (43.7%) was noted.

The significant correlation between ID and poor performance status in our patients was mainly due to the strong correlation between these parameters noted in patients with solid tumors. Presently, it cannot be distinguished whether this reflects the impact of more advanced disease on performance status with ID only being a surrogate marker of advanced disease, or whether this is due to the correlation between ID and anemia with both of them contributing to poor performance status. In contrast, in the patients with hematological malignancies, ID was evenly distributed between patients with good and poor performance status, while anemia was closely associated with poor performance status, a finding which we have noted already before [1]. In non-malignant diseases, ID has been found to correlate with significant impairment of physical, immune, and cognitive function, as well as fatigue among other symptoms [12, 21]. In our opinion ID likely is one of the contributing factors for reduced performance status, but others such as the sequels of cancer and cancer therapy supposedly are of greater importance.

In conclusion, our study shows a high prevalence of ID, mainly as FID, across different tumor types. ID and anemia correlated with tumor stage, status of the disease, performance status and was associated with close proximity to cancer therapy in patients with solid tumors, while in hematological malignancies anemia only correlated with the aforementioned parameters. Iron status should routinely be assessed in cancer patients particularly in those scheduled for or being on treatment with erythropoietic agents but importantly also in those without anemia, because timely commencement of iron therapy may prevent the occurrence of anemia, correct existing anemia and ameliorate symptoms of ID.

disclosures

HL has received consulting and speaker honoraria, Vifor Pharma Ltd., Switzerland. All the remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

acknowledgements

We thank Patrick Moneuse (Vifor Pharma Ltd., Switzerland) for statistical support and Brigitte Klement, Timothy Cushway, Beate Rzychon (all Vifor Pharma Ltd., Switzerland) and Walter Fuerst (SFL Regulatory Affairs & Scientific Communication, Switzerland) for valuable discussions and Bettina Dümmler (SFL Regulatory Affairs & Scientific Communication, Switzerland) for editorial support and Raphaela Oswald for preparation of the figures. The study was in part supported by the Austrian Forum against Cancer.

references

- 1.Ludwig H, Van BS, Barrett-Lee P, et al. The European Cancer Anaemia Survey (ECAS): a large, multinational, prospective survey defining the prevalence, incidence, and treatment of anaemia in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2293–2306. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grotto HZ. Anaemia of cancer: an overview of mechanisms involved in its pathogenesis. Med Oncol. 2008;25:12–21. doi: 10.1007/s12032-007-9000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuvibidila SR, Gauthier T, Rayford W. Serum ferritin levels and transferrin saturation in men with prostate cancer. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:641–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beale AL, Penney MD, Allison MC. The prevalence of iron deficiency among patients presenting with colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:398–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beguin Y, Lybaert W, Bosly A. A prospective observational study exploring the impact of iron status on response to darbepoetin alfa in patients with chemotherapy induced anemia. Blood. 2009;114 abstract 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinmetz HT, Tsamaloukas A, Schmitz S, et al. A new concept for the differential diagnosis and therapy of anaemia in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:261–269. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0812-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Inc. NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology; Cancer and chemotherapy-Induced Anemia—v.2.2012. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. (7 March 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aapro M, Osterborg A, Gascon P, et al. Prevalence and management of cancer-related anaemia, iron deficiency and the specific role of i.v. iron. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1954–1962. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beguin Y. Prediction of response and other improvements on the limitations of recombinant human erythropoietin therapy in anemic cancer patients. Haematologica. 2002;87:1209–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wish JB. Assessing iron status: beyond serum ferritin and transferrin saturation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:S4–S8. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01490506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brownlie T, Utermohlen V, Hinton PS, et al. Tissue iron deficiency without anemia impairs adaptation in endurance capacity after aerobic training in previously untrained women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:437–443. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verdon F, Burnand B, Stubi CL, et al. Iron supplementation for unexplained fatigue in non-anaemic women: double blind randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;326:1124–1126. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krayenbuehl PA, Battegay E, Breymann C, et al. Intravenous iron for the treatment of fatigue in nonanemic, premenopausal women with low serum ferritin concentration. Blood. 2011;118:3222–3227. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-346304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anker SD, Comin CJ, Filippatos G, et al. Ferric carboxymaltose in patients with heart failure and iron deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2436–2448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auerbach M, Ballard H, Trout JR, et al. Intravenous iron optimizes the response to recombinant human erythropoietin in cancer patients with chemotherapy-related anemia: a multicenter, open-label, randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1301–1307. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gafter-Gvili A, Rozen-Zvi B, Vidal L, et al. Intravenous iron supplementation for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced anemia—systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:18–29. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.702921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1011–1023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson KA, Hutchinson SM. Assessment of iron status and the role for iron-replacement therapy in anaemic cancer patients under the care of a specialist palliative care unit. Palliat Med. 2009;23:406–409. doi: 10.1177/0269216308101210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spielmann M, Luporsi E, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Diagnosis and management of anaemia and iron deficiency in patients with haematological malignancies or solid tumours in France in 2009–2010: the AnemOnHe study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;48:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludwig H, Aapro M, Beguin Y, et al. Frequent use of blood transfusions in current treatment practice for chemotherapy-induced anemia counteracts treatment recommendations aiming for less transfusions. Haematologica. 2011;96:abstract 407. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruner AB, Joffe A, Duggan AK, et al. Randomised study of cognitive effects of iron supplementation in non-anaemic iron-deficient adolescent girls. Lancet. 1996;348:992–996. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)02341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]