Abstract

Study Objective

In the context of calls to develop better systems for out-of-hospital clinical research we sought to understand: 1) paramedics’ perceptions of involvement in research, and 2) the barriers and facilitators to their involvement in research.

Methods

Qualitative study. Semi-structured focus groups with 58 UK paramedics and interviews with 30 US firefighter-paramedics. The research focused on out-of-hospital research (trials of pre-hospital treatment for stroke) whereby paramedics identify potential study subjects or obtain consent and administer study treatment in the field. Data were analysed using a thematic and discourse approach.

Results

Three key themes emerged as significant facilitators and barriers to paramedic involvement in research: ‘patient benefit’, ‘professional identity and responsibility’ and ‘time’. Paramedics showed willingness and capacity to engage in research but also some reticence due to the perceived sacrifice of autonomy and challenge to their identity. Paramedics work in a time sensitive environment and were concerned that research should not increase time taken in the field.

Conclusions

Awareness of these perspectives will help with development of pre-hospital research protocols and potentially facilitate greater participation.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital clinical research involving Emergency Medical Services (EMS) has been identified as a priority (1). The ethical and practical difficulties of obtaining informed consent (2–8) and the lack of infrastructure for conducting randomised clinical trials in the EMS setting (1, 9–12) makes research in out-of-hospital settings challenging (13, 14). Myers, for example, raised concerns regarding task performance, citing ‘inconsistencies in investigational protocol compliance, and actual or perceived resistance to participation in research by EMS personnel and receiving facilities’(9). The Committee on the Future of Emergency Care states: ‘most EMS personnel in the field do not consider themselves part of the research process and may resent any added paperwork requirements’ (14).

Practitioner reluctance to engage in randomised controlled trials is not unique to EMS settings. Common barriers to clinician involvement in research include limited time, lack of staff training, concerns about doctor/patient relationships, autonomy issues, difficulties with consent and lack of reward and recognition (15–18). Nonetheless, development of better systems of pre-hospital research in the field (19, 20)_ENREF_2 has been identified internationally as a high priority for out-of-hospital clinical research (21)_ENREF_4. Paramedic involvement in out-of-hospital research is key to this development. In order to better understand how research could be integrated into paramedic work it is necessary to consider the context of their work. Paramedics commonly operate outside ‘normal’ working hours (22). They work under high levels of stress associated with traumatic exposure to health emergencies (23) (24) and with institutional time pressures to meet ‘response time targets’ for different conditions (25). Research describing the nature of paramedic practice (26) is limited and, to our knowledge, there has been no examination of paramedics’ perspectives on involvement in out-of-hospital research. We therefore undertook a qualitative study in two settings (UK and USA) to examine paramedics’ perceptions of involvement in pre-hospital research.

Methods

Design

We report a qualitative study undertaken to understand the views and perspectives of paramedics about involvement in out-of-hospital research. This formed part of transdisciplinary (27) (biomedical and social science) research to develop and evaluate paramedic involvement in research about pre-hospital treatment interventions for stroke care. We undertook focus group (large group) interviews with a convenience sample of UK paramedic team leaders (hereafter UK paramedics) in order to gain an understanding of their views on involvement in out-of-hospital care and research, specifically a proposed trial of stroke pre-hospital interventions. Recruitment and data collection were designed to accommodate local differences and work practices, and for the convenience of participants. We report the findings related to research here. In parallel, we conducted individual and small group interviews with US paramedics (hereafter US paramedics) who were actively engaged in recruiting patients to the the NIH Field Administration of Stroke Therapy - Magnesium (FAST-MAG) Phase 3 Trial, the first-ever pivotal trial of prehospital stroke therapy (28, 29). The research protocol was developed collaboratively by UK based researchers (MM, DBW, JM, GF, CP,) and members of the FAST-MAG trial team (JLS, SS, ME, RS, RC, AG).

All authors reviewed the protocol and analysis for this paper. Site specific protocols received a favourable ethical opinion from the Durham Research Ethics Committee, UK, and Western Institutional Review Board, USA.

Setting

The UK study was part of an integrated program of research aimed at Developing and Assessing Services for Hyper-acute Stroke (DASH), specifically to identify the optimal organisation of pre-hospital and acute stroke care and to improve outcomes for stroke patients by enhancing the evidence base for future health service interventions. One aim of the DASH program was to implement a pre-hospital feasibility trial of a drug to reduce blood pressure with consent and drug administration by paramedics from the North East Ambulance Service (NEAS). The NEAS provides primary emergency services for 2.65 million people in rural and urban areas of the North East of England.

In the USA, the NIH-NINDS FAST-MAG trial is a multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase 3 trial with two objectives: 1) performing a pivotal evaluation of the promising neuroprotective agent magnesium sulfate in acute stroke, and 2) demonstrating for the first time that field enrollment and treatment of acute stroke patients is a practical and feasible strategy for phase 3 stroke trials, permitting enrollment of greater numbers of patients in hyperacute time windows. FAST-MAG is being conducted within the Los Angeles County Emergency Medical Service (EMS) Agency, the largest county EMS service in the US, serving 10 million residents. Paramedic services are integrated with the fire service. Prior to involvement, all paramedic participants received a two hour training package from the FAST-MAG research nurses on protocol and consent procedures, followed by brief refreshers every six months. Recruitment procedures for FAST-MAG are detailed elsewhere (30, 31)

Paramedic training in the UK and USA follow different trajectories. UK paramedics either secure a student paramedic position with an ambulance service trust, or attend an approved full-time course in paramedic science. In the USA, all firefighters in Los Angeles County are trained as EMT's. In order to become a paramedic, firefighters attend an intensive 6 month paramedic education program, and are required to pass a registry exam in addition to their firefighter/EMT role. In the UK and US paramedics are required to attend ongoing continuing education.

Selection of participants and recruitment

In the UK paramedic team leaders were recruited from the North East Ambulance Service (NEAS) through regular Service Improvement Program (professional training) meetings. Paramedic team leaders are experienced and highly trained paramedics with supervisory responsibility for front line staff including Paramedic Practitioners, Paramedics, Technicians, Emergency Care Assistants or Ambulance Care Assistants. Recruitment was opportunistic to coincide with the team leader service improvement days (a regular quarterly rotation of training days which all the paramedic team leaders from the regions are expected to attend for one day). Recruitment (i.e. inclusion of the focus group in the training day schedule) ceased when theoretical saturation was reached, that is, when no new themes or issues were forthcoming. This was assessed by MM, DBW and JM. Whilst attendance at a training day was mandatory for the paramedic team leaders, participation in the focus groups was voluntary. The research team were allocated a session within each of the days and all paramedic team leaders were invited to participate.

Paramedics in the USA were purposively sampled based on their level of participation in the FAST-MAG Phase III Clinical Trial. Paramedics were recruited from across LA County, LA City and incorporated City fire departments from three groups of fire stations and across eight paramedic rescues teams: four high recruiting teams (rescues with greater than eight enrolments), three low (between one and three enrolments) and one rescue team whose members had so far not recruited any patients. This selection approach ensured inclusion of a range of paramedic opinion, including individuals strongly and less strongly supportive of research activities. Paramedics interviewed had enrolled from zero to six patients. All paramedics interviewed had been trained in the study procedures. Recruitment ceased when theoretical saturation was reached in each of the categories. This was assessed by MM and DBW.

Data collection and analysis

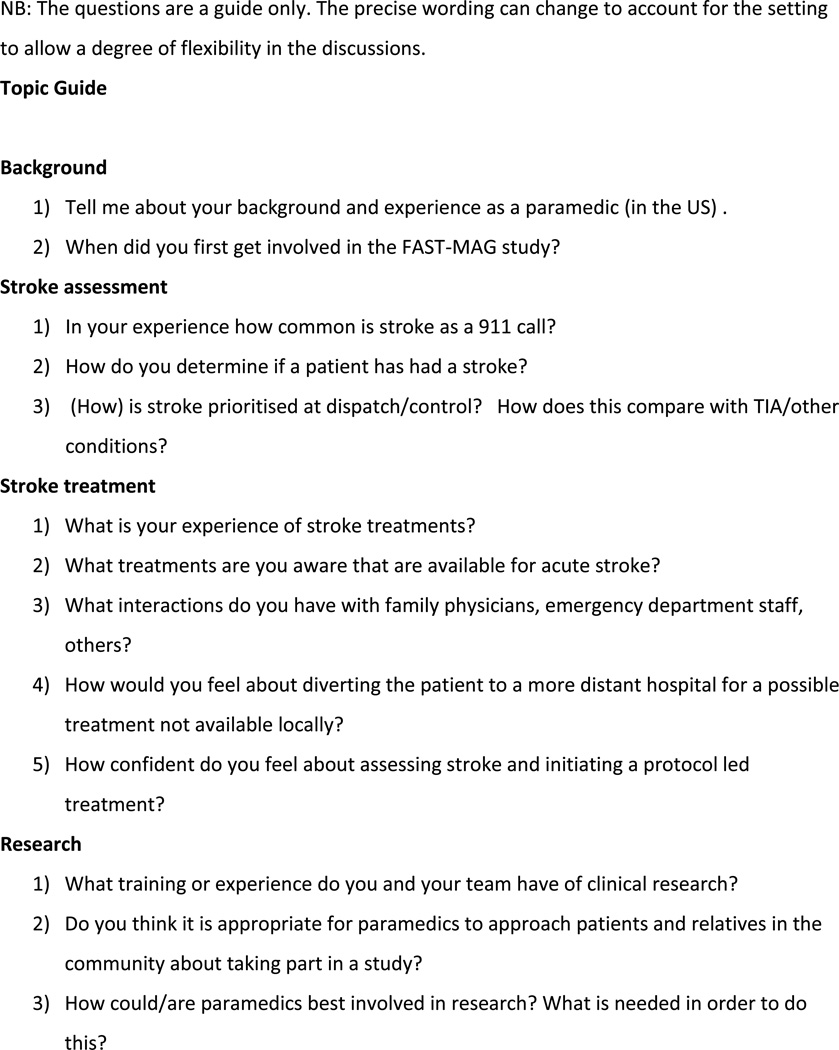

All focus groups and interviews were conducted in the paramedics’ places of work. Focus groups and interviews followed a topic guide (see Figure 1) to elicit discussion on three main topics, with minor changes to account for differences in each setting. These were: their experiences as paramedics; their knowledge of stroke, stroke treatments and stroke assessment; and familiarity with and perspectives on research, research training needs and how best to involve paramedics in research. In addition, the US paramedics were asked about their involvement in the FAST-MAG trial. The topic guide was administered consistently (i.e. all topics covered) across all focus groups and interviews but allowed flexibility to enable other issues to emerge.

Figure 1. Topic guide.

Focus groups and interviews were facilitated, conducted and analysed by UK based qualitative researchers who had no direct involvement in the FAST-MAG trial or the UK stroke study (DBW, JM, MM). The qualitative researchers were not associated with the medical direction or supervision of the paramedics. Nor were GF, AG, CP, JLS, SS, RS involved in such supervision, although these were all directly involved in the development or conduct of out-of-hospital trials of pre-hospital stroke treatment. Participants were not previously known to the researchers conducting the focus groups and interviews.

Anonymised transcripts of the audio-recorded focus groups and interviews formed the data for analysis. Focus group and interview were analysed separately and then as a whole using thematic analysis (32, 33). Qualitative thematic analysis involves searching for patterns (or themes) within the data; in this case the transcripts of focus groups and one-to-one interviews. Emerging themes within single transcripts were compared across all transcripts for similarities, continuities and discontinuities. Analysis of these patterns across the corpus of data comprising focus groups and interviews allowed insight into the perspectives of the participating paramedics. Thematic analysis allowed identification of the context and cultures of paramedic practice and the barriers and facilitators to their involvement in research. The process of thematic analysis followed the framework method (32); an analysis technique widely used in qualitative research and described in detail below. Field notes were taken for focus groups and interviews by JM and DBW.

Specific steps in the framework method of analysis were as follows. Each of the transcripts was read and re-read by the researchers (DBW, JM, MM), following which a coding framework was devised. Coding (selection of data extracts representative of each code) was undertaken by one person (JM – UK focus groups; DBW – US interviews), and was discussed and revised by MM, DBW and JM. Thematic categories were applied to each transcript coded using the NVIVO software package (QSR International 2000) and then 'charted', a process by which key points of each data extract were summarised and documented on a cross-sectional matrix. Derived categories were discussed by JM and DBW employing a 'pragmatic' version of double coding (34). Thus, a set of categories was obtained which described the main themes arising from the interviews. The resulting themes were then considered in terms of discourse analysis (35). Discourse analysis draws attention to the ways language shapes meanings and representations of the ‘lived in’ world. The words participants chose for their description reference wider understandings of the way the(ir) world works. These understandings will differ among individuals dependent upon experience, values, political views, social position etc. In other words, participants use ‘discourses’ (their version of the world) to interpret and present descriptions of that world. Representations were therefore interrogated by experienced practitioners of discourse analysis (MM and DBW) to gain a richer understanding of the cultures and customs encoded in the participants’ speech. Preliminary analyses from the thematic and discourse analytic processes were presented in different for a (presentations to paramedics, multidisciplinary research team meetings in the UK, via email with researchers in the US and international social science meetings) to check and challenge the interpretations made. Following thematic and discourse analysis our findings were compared to existing literature in the field.

Results

In the UK, 58 paramedics attended seven focus groups, ranging in size from five to 12 participants. The length of experience of the paramedics in the study spanned 2 to 22 years. All had worked in the ambulance service before becoming paramedics. In the US, 22 paramedics were interviewed: 7 one on one interviews and 3 paired interviews from teams with high recruitment, 3 paired interviews from teams with low recruitment and one group of 3 paramedics from a team with no recruitments. Each group included paramedics working with mixed experiences of urban, suburban and rural areas.

Our findings are that three key themes emerged: ‘Patient benefit’, ‘Professional identity and responsibility’ and ‘Time’. We also considered factors promoting and inhibiting maintenance of involvement in research and describe the rationales for practice produced by these discourses. Drawing on these findings, we present strategies for involving paramedics effectively in pre-hospital research taking into account these discourses of professional identity and practice.

Patient benefit

Paramedics identified the key goal and focus of their activities as ensuring that patients in their care were given access to right treatments, in the right settings, as quickly as possible. Views on barriers and facilitators to research involvement for both UK and US paramedics were thereby oriented to perceived treatments and health outcomes for patients. Patient benefit was equated with enabling access to treatment. Paramedic involvement in research was therefore understood as: 1) a treatment in the absence of alternatives; 2) providing a way of helping to produce a ‘cure’; and, 3) providing the possibility of a direct and immediate impact for their patient from the trial drug (Table 1). All three possible reasons for involvement in research oriented to hope.

Table 1.

Patient benefit

|

Patient benefit and hope For us, before FAST-MAG we didn’t have anything; we gave them oxygen and transferred them to hospital and that was it. (US-FS4 (Fire Station 4)) |

| [I was] optimistic and thought here’s an opportunity to cure one of the worst debilitating diseases or injuries that you can see in pre-hospital care and you know that the outcomes are typically terrible (US-FS4) |

| The way I look at every call, I'm looking at it’s like my mom or dad, what's the best thing to do? “Hey, you know what? This trial study looks good. What do you think about it? There’s no guarantee that you're getting the medicine. Maybe you're getting it, maybe you're not. But you know what? You could make a difference.” (US-FS6) |

|

Patient benefit and randomisation I think the paramedics would want to give a definitive treatment, rather than be randomised and say that as [another paramedic] said we give them drug x or drug y, not knowing what it is. Currently we all stick by protocols, protocols are that we give drug a for that, drug b for that and rather than randomise what you are giving the patient, we currently give them definitive treatments and I think the majority of paramedics would rather stay on that. (UK-FG4) |

| I knew it was a triple blind study, so I knew that we weren’t necessarily… because they kept telling us we’re not going to see the results; but I was optimistic that we would see something in the field and there’s been a few cases where we’ve seen a change. (US-FS4) |

| when you, you introduce something as a study as that where you don’t know who is getting the medication who is not whether the patients are going to benefit from it and whose not and you, it’s not really for us it’s not outcome based even though [name] will tell who gets it because we see the reaction of the patient and stuff like that so we, we basically know who’s getting the medication who’s getting a placebo. It’s just we don’t see long term facts at all in EMS (US-FS2) |

|

Patient benefit and trust If you’re elderly and a bit confused, I mean I’d feel like a salesman getting people to sign agreements to say they wanted their windows. But just because you’re official they go “Oh yeah, I want it” (UK-FG2) |

Patient benefit and good patient outcomes were understood to be achieved by rapid access to definitive treatments. Randomisation in a trial therefore presented the possibility of nontreatment for their patient. Despite understanding that the blinded design of the trial meant that they would not be able to know the results of the trial until it was complete, paramedics talked of perceived treatment effects. One paramedic who had recruited four patients to the US study suggested that “only one … didn’t have any significant change …“ and another that “the patient was completely limp on the left side and just classic signs of a stroke, so they started him on FAST-MAG and by the time they got to the hospital after giving him the therapy the patient was already better…”. These examples are likely to represent paramedics’ accommodation of their experience, perceptions and concerns regarding randomisation in a trial on the one hand, with their orientation to patient benefit and hopes for positive patient outcomes on the other. Importantly, hope provided a rationale for investing time and energy in the possibility of positive outcomes from the research.

UK paramedics expressed concern about disruptions to the paramedic-patient relationship. Randomisation was viewed as a potential breach of trust. Some UK paramedics in thinking about prospective consent were uncomfortable about the blinded nature of the trial, i.e. paramedics felt they could not tell the ‘truth’ about whether the patient would be receiving treatment or placebo and honest relationships with their patients were seen as fundamental to their identity as paramedics. There was concern about the paramedic’s influence enrolling patients to trials based on the trust inherent in patient relationships with paramedics (Table 1).

Patient benefit and patient outcomes formed the key discourse around which paramedics formed their professional identity. That is, they saw themselves and their professional identity through the lens of ‘patient benefit’ and their relationships with patients and their families. The orientation to patient benefit is certainly not unique to paramedics. What is important here is that, in the context of paramedics’ work practices, the orientation to a particular understanding of ‘patient benefits’ defined and shaped paramedics’ views on involvement in research.

Professional identity and responsibility

An emerging professionalism in paramedic roles and training since the 1970’s in both the UK and US shaped paramedics’ identity and shaped their practice. The emergent professional identity of ‘the paramedic’ and accompanying professional autonomy (the capacity to exercise professional judgement in decision making) was linked to the changing nature of the health service in the UK and the fire service in the US. Increasingly the performance of paramedic duties had provided a greater level of professional autonomy and responsibility enabling the paramedic to manage events and influence outcomes ‘on scene’. Traditional images of a ‘scoop and run’ paramedic, strictly adherent to protocol-driven care and averse to change, who was likely to be sceptical about involvement in research contrasted with a newly emerging professional identity in which the adaptation to increasing medical roles within the service was welcomed. Paramedics in the US referred to themselves as ‘medics’. There was, however, some concern about lack of recognition of this emerging professionalisation in inter-professional relations. In this emerging professional identity the value placed on patient benefit produced a paramedic perspective which saw value in research participation. Strict research protocols could also limit autonomous practice. A concern was that sometimes the research, rather than the paramedic, managed care. Strict research entry criteria were perceived as potentially outweighing paramedic judgements about diagnosis/eligibility. Involvement in research, therefore, had the potential to both limit and to enhance professional identity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Identity and professionalization

| I think that we are more responsible for our own training and making decisions than we were when I first came on the road. When I first was a paramedic a patient had to fit the criteria in black and white … now you’ve got a whole range of things that you can do for somebody […] and it’s up to your own clinical making decisions and your own responsibilities, your own background knowledge to decide what treatment you’re going to give that patient and fortunately most of us have moved on and accepted that and we do do that but there’s still die-hards of the service who’ve had 30 odd years who are used to protocol driven treatments and won’t…do that because they think well if I make a mistake I’m going to be shot. (UK-FG3) |

| Probably 70, 75% of our emergency calls are EMS related, whether it’s hurt in traffic accidents or the chest pains etc. Erm, so the medics are dictating, pretty much controlling the scene, they are the ones in command on that on a medical call and the captain’s kind of in charge of safety making sure everybody’s safe, crowd control and that type of thing, and getting resources as needed. So I mean there's a lot of different roles going on. For me as a medic I love it because hey, you know what? I'm directly affecting this person and I get a little bit of the management scene control at the same time. But I've got my hands busy and get the best of both worlds. (US-FS1) |

| A lot of the problems are, we tend to find as well, the ignorance on behalf of doctors because they seem to think back to the old days where the ambulance turned up, you loaded the patient on, you buggered off. They don’t comprehend that these days a lot of us paramedics are autonomous clinicians…they can’t comprehend…that paramedics these days do 12 lead ECG, they use morphine and if need be we can thrombolyse [MI] patients. (UK-FG4) |

| It’s so stringently regulated and if you make mistakes you could blow the study and then you know it, so now it’s not only do you have okay I have a treatment of a patient that could be critically medically ill but now I have to follow these strict guidelines that if I screw up or, or step outside of the parameters of these guidelines I can be in extreme trouble. (US-FS6) |

Time

While discourses of patient benefit and professional responsibility were not unique to paramedics, the intensity of their orientation to time appeared to be. Even for the most enthusiastic paramedics, time-critical imperatives were perceived as a challenge to research involvement. Paramedic duties required fast decision making and getting patients to the hospital for rapid treatment. The institutional culture placed high importance on time-based prioritisation of activities, rather than ‘in field’ treatment. ‘Basic’ life support assessments were deemed a priority. Other activities were frequently perceived as additional or only possible if time permits. Thus the traditional paramedic role was not easily aligned with research (Table 3).

Table 3.

Time

| By the time we get a patient onto a vehicle, we tend to do obs en route to hospital … then by the time we fill in the paperwork you might have a few minutes for a bit nicety with the relative and the patient. But you haven’t got a great deal of time to start explaining a trial or receiving permission to do something. (UK-FG6) |

| We’re pre-hospital. So decisions have to be made in a pretty expeditious manner. Ruling out if a patient is critical or non-critical supersedes everything else. (US-FS2) |

| we were in the shadow of the hospital, literally, the shadow of the hospital was on top of the building that we were inside of. So we had to be quick, you know. (US-FS6) |

| ‘Why are we doing this when we can have the patient at the hospital and they could be receiving the actual medication rather than a placebo in the field where it may not change the outcome of the patient one way or another?’ So guys were apprehensive of being in a study. Let’s either do something that’s going to benefit a patient or not do it all. (US-FS5) |

| For paramedics a minute feels like an hour. (Fieldnote from discussion after interviews) |

Eliciting explicit informed consent, though often a necessary procedure for research, was regarded as potentially leading to time delay and in tension with the priority to transport patients to the hospital as quickly as possible. For the US paramedics their greatest concern was that the FAST-MAG system for performing research and treatment in parallel succeed in its goal of avoiding delays in time to treatment. The contrasting priorities of patient benefit and research were magnified when paramedics were within close proximity of the hospital, ‘in the shadow of the hospital,’ where the potential benefit of any additional time taken for research purposes was overshadowed by the priorities of the paramedic’s practice, i.e. to get the patient to treatment as quickly as possible (Table 3). For paramedics, a minute felt like an hour. The time taken to enrol (or attempt to enrol) patients was regarded as potentially extending time in the field. US paramedics were concerned about spending time on the phone, ‘just talking to the doctor’, and reported that this interval varied from seconds to 20 minutes depending on the recruiting doctor. However, detailed records taken by the FAST-MAG researchers suggest the time interval from paramedic arrival on scene to ED arrival was not lengthened by involvement in research (29, 30). The parallel design of the enrolment process in FAST-MAG (patient speaking to physician by phone while paramedics perform usual care activities) minimized research delays in the field but was perceived by paramedics as limiting their authority to change the time spent on scene (Table 3).

While UK paramedics were greatly concerned about the potential problems associated with the additional time taken for research, it is the interviews with US paramedics that best demonstrate how discourses of paramedic identity play out in relation to the experience of involvement in research. Where screening did not lead to participation, paramedics were concerned that this undermined their credibility with patients. This was particularly acute if no explanation was provided for why the patient was unsuitable for research (Table 3).

Maintaining research involvement

At the time of this study, FAST-MAG had recruited more than 500 subjects. For trial coordinators the recruitment of the first 500 patients marked a substantial milestone and achievement. For paramedics, as the trial progressed, the task of recruitment was increasingly seen as onerous “Sure, it’s a lot of work to not have any results”. Trial fatigue is a common finding for trials of long duration (36). The paramedics were not deterred from continuing their involvement; clearly they did continue. However this does highlight the necessity for ongoing acknowledgement of participants’ involvement. This requires providing explanations about why large numbers are needed in the research and education and regular updates regarding research decisions and processes, as implemented in FAST-MAG by regular newsletters and ambulance station visits.

Active involvement was one means by which recognition of professional identity was reinforced. Involvement in research development in both the UK and US studies represented an acknowledgment of paramedics’ expertise and provided a mechanism for ‘buy in’ to the research. This was also a means by which professional identity was recuperated. The advantages of involving experience-rich participants in research design is well established (37, 38). Moreover, involvement in the development of research was suggested as one way in which those paramedics seen as less amenable to change per se could be encouraged to ‘buy into’ the research. The principle of voluntary involvement was advocated, citing professional identity and patient benefit as a motive for involvement (Table 4).

Table 4.

Involving paramedics in the research process

| Our fire chief that was here at the time and he was instrumental in design: the drip tubing, the dosage was administered at the proper rate so that it was administered over the fifteen minutes in a pre-hospital setting. He was instrumental in organising the fire service aspect of it and being the interface between the hospital side and the pre-hospital side. We were helping him figure those things out. (US-FS4) |

| Interviewer: For somebody like us doing research, how would we find the right people to involve? Paramedic: Volunteers, I think. You would ask for volunteers first of all, wouldn’t you. There’s going to be some there because they just want the kudos of being able to do it as well. But most of them will want to do it because they’ll want to do it… for the benefit of the patient. (UK-FG3) |

| Once you have people out there that are doing it there will be more and more people that want to do it. (UK-FG3) |

Limitations

This was a study of paramedic perspectives on emergency pre-hospital research in the context of stroke. While some of the responses may therefore be specific to the stroke setting it is likely that much the perspectives presented here are theoretically generalisable to other pre-hospital research involving paramedics. The research method employed here, semi-structured qualitative interviews, brings with it an accepted limitation of the method. Interview and focus group accounts represent participants’ perceptions of reality. This is not the same as the researchers witnessing reported events and we can therefore present only reports of practice, not observations of the practice itself. Participant accounts must therefore be understood within constraints of interpretation that include differential understandings and perspectives of the qualitative researcher and participant. Standard mechanisms of ameliorating these constraints include checking interpretations with participants or other groups, presenting sufficient raw data to enable the reader to assess the veracity of interpretations and accounting for the potential biases individual researchers may bring to analysis. For this qualitative study we, firstly, presented preliminary results to paramedic groups (including but not exclusively from the participant pool) and at local and international academic meetings. We incorporated feedback in our final interpretations. Secondly, we present representative extracts of raw data to accompany the results above. Thirdly, we have accounted for the potential biases of the qualitative researchers (MM, DBW and JM) undertaking the key aspects of data collection and analysis by making them evident here and applying the methods above to check for skewed interpretation. Each of these researchers are UK based social science (DBW, MM) and health service research (JM) researchers with qualitative research experience ranging from 10 (DBW and JM) to 18 (MM) years. None had any connection with clinical trials or previous work with EMS. None are paramedics or have an EMS background; each has travelled to and/or lived in the US. Lack of insider knowledge of paramedic or US culture might provide a basis for misinterpretation. Equally, the distance provided by an external perspective can reveal nuances not available to the initiate.

Discussion

In this study we identified barriers and facilitators to paramedics’ involvement in research. We identified two key issues with the potential to limit willingness to be involved in research. First, the perceived threat of research to professional autonomy and practice. Second, a perception of a disjuncture between treatment and research, particularly in conflicts over the priorities for how time is spent.

Threats to professional autonomy and practice

Paramedic work occurs in disorganised, chaotic and risky environments. The paramedic must organise this chaos to enable the delivery of healthcare and any research taking place in this setting. This involves complex social, temporal and spatial management. Unsurprisingly, this on-scene management is critical to the formation of paramedics’ professional identity (26). Decisive action was key to successful on-scene management. Success was measured in terms of rapid patient access to acute treatments, specifically rapid admission to Emergency departments (39). Time based performance measures were therefore a leading standard by which involvement in research was assessed. The altered focus brought about by involvement in research meant paramedics perceived they no longer directed all events on scene and that they were sometimes waiting on events/activities outside their control. Involvement in research was viewed as inhibiting autonomous practice. Time spent on scene obtaining consent involved the diminution of their autonomy as clinicians. Research processes were understood as potentially ‘taking time’ in ways that were not consistent with their time-sensitive culture within the service. Mirroring the effects of community based participatory research (37), the FAST-MAG investigators have, over the course of the study, made several changes in trial procedures to increase paramedic responsibilities and reinforce paramedic professional identity. The study screening form used by paramedics was expanded to include several additional key exclusion criteria. This change enabled paramedics to make decisions to exclude a greater proportion of patients rather than waiting on decisions from study physicians. The study newsletter is sent to all participating fire stations every two months and highlights the enrolling paramedics, the number of patients enrolled by each participating EMS Provider agency, and key items of paramedic study performance. Before study commencement, and throughout the period of study performance, paramedic representatives served on the Study Steering Committee and on the Study Paramedic Operations Committee. They played active roles in shaping study procedures to fit with paramedic practice and culture.

The disjuncture between treatment and research

Throughout discussions of involvement in research, paramedics sustained a distinction between research and treatment. Paramedics’ view was that treatment, not research, was rightly the goal of their practice. This separation of treatment and research has quite specific rhetorical effects. Separating research from treatment provides a rationale - through the deployment of discourses of patient benefit, professional responsibility and time - for limiting involvement in research. We were told by paramedics that research was a poor alternative to treatment. A paramedic’s responsibility was to make decisions ‘on scene’ that would facilitate speedy access to treatment (in a hospital). The contrasting priorities of treatment and research were amplified when time was limited. Time taken for research was perceived as necessarily delaying a patient’s access to treatment. Certainly research was an opportunity to test a treatment in the field but the treatment not the test was the focus of their professional practice.

This disjuncture between treatment and research is not a necessary truth and did not result in wholesale rejection of research. Competing and sometimes contradictory discourses provided the rationales for (non)involvement in research. Discourses of professional identity provided both a rationale for positive and negative responses to research. Research as a threat to professional autonomy could discourage involvement in it but discourses of professionalisation could provide a rationale for engaging in the higher level activities represented by research. These potentially contradictory views of involvement in research are part of the social complexity that is transdisciplinary research (40).

Conclusion

Our findings support previous reports that the response of paramedics to research is contradictory (41). Most supported the idea of research for patient benefit ‘in principle’, but some paramedics lacked enthusiasm for the research and a small number resented being involved in research. Importantly, the barriers to research involvement are potentially amenable to change. The findings of this study subsequently shaped the design and development of a new pre-hospital trial in the UK as part of the DASH programme and refined the implementation of the FAST-MAG Trial in the US. In the UK recognition of the importance to patients of new early stroke treatments and of paramedics’ potential professional role in facilitating out-of-hospital research led to the development of a research protocol which incorporated paramedic led consent, supported by clinical input if necessary. The protocol procedures recognised the time sensitivities of paramedics and addressed their concerns about randomisation via education about the purpose of randomisation. In the US, the study findings led to further devolution to paramedics of study exclusion determinations and intensified communication to paramedics of study success in avoiding delay in time to treatment and overall trial progress.

As noted above, transdisciplinary research is a complex enterprise. Nonetheless, lessons can be learned and applied elsewhere. The attention to the social dimensions of multidisciplinary involvement in research can pay dividends in realising research outcomes. Keys to success in pre-hospital research undoubtedly include involving paramedics at the research design stage, and during the trial, demonstrating the impact of ongoing research on in the field assessment time, keeping paramedics informed of developments and enrolment rationales in ways that are meaningful to them and their priorities.

Acknowledgements

We would firstly like to thank the paramedics who gave their time to this study. We are grateful for the support of Terry Lisle, Alison Etherington and Naomi Woodward of the Risk Communication and Decision Making Research Programme, Institute of Health and Society, Newcastle University, in co-ordinating the study, setting up the database and transcribing interviews. We are grateful to those who facilitated access to paramedic services and supported the study; Frank Pratt, Department of Emergency Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, and Los Angeles County Fire Department, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Sam Stratton, Department of Emergency Medicine, Harbor UCLA Medical Center, and Los Angeles Emergency Medical Services Agency, Los Angeles, CA, USA, Colin Cessford, North East Ambulance Trust, UK. We would also like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier drafts.

Declaration of interest: This interview study forms part of an integrated program of research on Developing and Assessing Services for Hyper-acute Stroke (DASH) conducted in England. This incorporates an international comparative component involving the Field Administration of Stroke Therapy - Magnesium (FAST-MAG) Phase 3 Trial. DASH is funded by the UK-based National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). FAST-MAG is funded by the US-based National Institutes of Health (NIH). This article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research (RP-PG-0606-1241). GAF is supported by an NIHR Senior Investigator Award. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the UK the Department of Health or the NIH. Supported in part by NIH-NINDS Award U01 NS 44364.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sayre M, White L, Brown L, McHenry S. National EMS Research Agenda. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2001;6(3 Suppl):S1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kane I, Lindley R, Lewis S, Sandercock P. Impact of stroke syndrome and stroke severity on the process of consent in the Third Internatinal Stroke Trial. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21:348. doi: 10.1159/000091541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stobbart L, Murtagh MJ, Louw SJ, Ford GA, Rodgers H. Consent for research in hyperacute stroke: Essential studies in the first six hours are hampered by rules on consent. BMJ. 2006;332:1405. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7555.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White-Bateman SR, Schumacher HC, Sacco RL, Appelbaum PS. Consent for Intravenous Thrombolysis in Acute Stroke: Review and Future Directions. Arch Neurol. 2007 Jun 1;64:785. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.6.785. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciccone A. Consent to thrombolysis in acute ischaemic stroke: from trial to practice. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:375. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lecouturier J, et al. Consent and capacity in recruitment of stroke patients to acute trials: a review. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangset M, Forde R, Nessa J, Berge E, Wyller TB. "I don't like that, it's tricking people too much…": acute informed consent to participation in a trial of thrombolysis for stroke. BMJ. 2008;34:751. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.023168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flaherty M, et al. How important is surrogate consent for stroke research? Neurol. 2008;71:1566. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316196.63704.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myers JB. Evidence-Based Performance Measures for Emergency Medical Services Systems: A Model for Expanded EMS Benchmarking. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2008;12:141. doi: 10.1080/10903120801903793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrison H, Brice J. Research and Evaluation in Out of Hospital Emergency Medical Services. North Caroline Med J. 2007;68:246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson J. Ethical challenges of informed consent in prehospital research. Can J Emerg Med. 2003;5:108. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500008253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pancioli A, Barsan W, Conwit R. Executive summary: The Emergency Neurologic Clinical Trials Network meeting--a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke symposium. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2004;11:1092. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang HE, Yealy DM. Emergency Medical Services System Research: Challenges and Opportunity. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2007;50:643. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Emergency Medical Services at the Crossroads. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2007. I. o. M. o. t. N. Academies, Ed., [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross S, et al. Barriers to Participation in Randomised Controlled Trials A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52:1143. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Somkin CP, et al. Cardiology clinical trial participation in community-based healthcare systems: Obstacles and opportunities. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29:646. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abraham NS, Young JM, Solomon MJ. A systematic review of reasons for nonentry of eligible patients into surgical randomized controlled trials. Surgery. 2006;139:469. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kao LS, Tyson JE, Blakely ML, Lally KP. Clinical Research Methodology I: Introduction to Randomized Trials. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2008;206:361. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vascular Programme - Stroke, Department of Health. Crown, London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acker JE, III, et al. Implementation Strategies for Emergency Medical Services Within Stroke Systems of Care: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association Expert Panel on Emergency Medical Services Systems and the Stroke Council. Stroke. 2007 Nov 1;38:3097. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.186094. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snooks H, et al. What are the highest priorities for research in pre-hospital care? Results of a review and Delphi consultation exercise. Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care. 2008;6 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubery J, Ward K, Grimshaw D, Beynon H. Working Time, Industrial Relations and the Employment Relationship. Time Society. 2005 Mar 1;14:89. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regehr C, Millar D. Situation Critical: High Demand, Low Control, and Low Support in Paramedic Organizations. Traumatology. 2007 Mar 1;13:49. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeBlanc VR, Regehr C, Jelley RB, Barath I. Does Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Affect Performance? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:701. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31811f4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price L. Treating the clock and not the patient: ambulance response times and risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Apr 1;15:127. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015651. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campeau A. Why Paramedics Require “Theories-of-Practice”. Journal of Emergency Primary Health Care. 2008;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibbons M, Nowotny H. The potential of transdisciplinarity. Transdisciplinarity: joint problem solving among science, technology, and society. 2000:67. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saver J, Kidwell C, Eckstein M, Starkman S. FAST-MAG Pilot Trial Investigators. Prehospital neuroprotective therapy for acute stroke: results of the Field Administration of Stroke Therapy-Magnesium (FAST-MAG) pilot trial. Stroke. 2004;35:106. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000124458.98123.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saver JL, Kidwell C, Eckstein M, Starkman S. F.-M. P. T. Investigators, Prehospital neuroprotective therapy for acute stroke: results of the Field Administration of Stroke Therapy-Magnesium (FAST-MAG) pilot trial. Stroke. 2004 May;35:e106. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000124458.98123.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saver J, Kidwell C, Eckstein M, Ovbiagele B, Starkman S. FAST-MAG Pilot Trial Investigators. Physician-investigator phone elicitation of consent in the field: a novel method to obtain explicit informed consent for prehospital clinical research. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10:182. doi: 10.1080/10903120500541035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanossian N, et al. Simultaneous Ring Voice-over-Internet Phone System Enables Rapid Physician Elicitation of Explicit Informed Consent in Prehospital Stroke Treatment Trials. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2009;28:539. doi: 10.1159/000247596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. The qualitative researcher’s companion. 2002:305. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potter J. Representing reality: Discourse, rhetoric and social construction. Sage Publications Ltd; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrei VA. Slow recruitment in clinical trials: failure is not an option! Int J Stroke. 2006;1:160. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2006.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American journal of public health, AJPH. 2010 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. 2009.184036 v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Viswanathan M. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. U. S. A. f. H. Research, Quality. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rajajee V, Saver J. Prehospital Care of the Acute Stroke Patient. Tech Vasc Interven Radiol. 2005;8:74. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murtagh MJ, Demir I, Harris JR, Burton PR. Realizing the promise of population biobanks: a new model for translation. Human Genetics. 2011;130:333. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1036-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price L, Keeling P, Brown G, Hughes D, Barton A. A qualitative study of paramedics' attitudes to providing prehospital thrombolysis. Emerg Med J. 2005 Oct 1;22:738. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.025536. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]