Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) comprise the largest superfamily of cell surface receptors, and are primary targets for drug development. A variety of detection systems have been reported to study ligand-GPCR interactions. Using Saccharomyces cerevisiae to express foreign proteins has long been appreciated for its low cost, simplicity, and conserved cellular pathways. The yeast pheromone responsive pathway has been utilized to assess a range of different GPCRs. We have identified a pheromone-like receptor, Cpr2, that is located outside of the MAT locus in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. To characterize its function and potential ligands, we expressed CPR2 in a yeast heterologous expression system. To optimize for CPR2 expression in this system, pheromone receptor Ste3, regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) Sst2, and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Far1 were mutated. The lacZ gene was fused with the promoter of the FUS1 gene that is activated by the yeast pheromone signal and then introduced into yeast cells. Expression of CPR2 in this yeast heterologous expression system revealed that Cpr2 could activate the pheromone responsive pathway without additional of potential ligands, suggesting it is a naturally-occurring, constitutively active receptor. Mutation of a single amino acid, Leu222, was sufficient to reverse the constitutive activity of Cpr2. In this report, we summarize methods used for assessing the constitutive activity of Cpr2 and its mutants, which could be beneficial for other GPCR studies.

1. Introduction of receptors and constitutive receptors

All living organisms must sense environmental signals and respond appropriately to survive. Sensing the environment depends on cell surface receptors, which include the family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (Bahn et al., 2007). GPCRs comprise the largest superfamily of cell surface receptors, which respond to a variety of extracellular stimuli as diverse as hormones, neurochemicals, odorants, nutrients, and light (Bockaert and Pin, 1999). Despite exhibiting diversity in primary sequence and biological function, all GPCRs possess the same fundamental architecture, consisting of seven transmembrane domains (7TMs), and share common mechanisms of signal transduction. These receptors are also of great pharmacological importance (Drews, 1996). To date, almost half of all clinically relevant drugs act as agonist or antagonists of GPCRs (Drews, 1996).

Generally, GPCRs function as guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) to activate heterotrimeric G proteins that play a central role in transducing extracellular signals into intrinsic signals and effecting appropriate biochemical and physiological responses. Ligand activation of GPCRs triggers the coupled Gα subunit to release GDP and bind GTP, transforming them into the Gα-GTP active state. The GTP binding results in a conformational change of the Gα subunit, which promotes its dissociation from the Gβγ complex. The liberated Gα or Gβγ subunits then interact with downstream effectors to switch on or off signaling cascades. RGS (Regulators of G protein signaling) proteins, on the other hand, negatively regulate the G protein signaling by converting Gα protein from GTP-bound state to GDP-bound state.

Much of GPCR research has focused on the effects of agonist stimulation of these GPCRs, but it has become clear that many GPCRs exist in a constitutively active state, where activation occurs in the absence of an agonist. These GPCRs are locked in an active state and active downstream signal in a ligand-independent fashion, and continuously stimulate their intracellular signaling pathways (Rosenkilde et al., 2006). The hypothesis that some GPCRs can signal in the absence of any external ligand was first supported by studies of the opioid and β2-adrenergic receptors (Cerione et al., 1984; Koski et al., 1982). Constitutively active GPCRs have been generated artificially by mutagenesis, and also have been reported to exist as naturally occurring point mutations that increase constitutive activity (Van Sande et al., 1995). Moreover, approximately 60 wild-type GPCRs from human, mouse, or rat have been shown to exhibit considerable constitutive activity and many of them found to be linked to human diseases (Seifert and Wenzel-Seifert, 2002). Therefore, constitutively active GPCRs may be of great physiological importance in both natural physiology and disease states.

A pheromone receptor-like gene, CPR2, was identified in Cryptococcus neoformans, a human fungal pathogen that commonly causes meningoencephalitis mostly in immunocompromised populations (Hsueh et al., 2009). Cpr2 appears to be a naturally occurring, constitutively active GPCR based on biochemical and genetic evidence: First, expression of CPR2 in a yeast heterologous expression system revealed that Cpr2 activates downstream signals without addition of potential ligands; second, a single amino acid, Leu222, was found to produce its constitutive activity. The constitutively active status of Cpr2 was further confirmed in phenotypic analysis and protein-protein interaction assays using a split-ubiquition system (Hsueh et al., 2009). In this chapter, we will discuss several methods used to assess GPCR constitutive activity in fungi using Cpr2 as an example.

2. Identification of Cpr2 as a natural occurring constitutively active receptor

2.1 GPCR and G protein signaling in C. neoformans

GPCRs have been identified in a variety of fungi and play important roles in cell development and fungal pathogenesis. The model ascomycete Saccharomyces cerevisiae has only three GPCRs: two pheromone receptors (Ste2 and Ste3) and one sugar sensor (Gpr1) (Burkholder and Hartwell, 1985; Hagen et al., 1986; Kraakman et al., 1999). The pheromones and pheromone receptors are expressed in a cell-type specific manner in S. cerevisiae. a cells express the lipopeptide pheromone a-factor and the α-factor receptor Ste2 whereas α cells express the peptide pheromone α-factor and the a-factor receptor Ste3. Ste2 and Ste3 activate Gpa1 G protein to regulate the pheromone-responsive pathway, while Gpr1 is coupled to Gpa2 to control the nutrient sensing of yeast cells (Harashima and Heitman, 2004; Lengeler et al., 2000). The Gpa1-pheromone response pathway is among the best understood signaling pathways in eukaryotes and serve as a model for GPCR-mediated signaling. Studies of this model have contributed enormously to the understanding of the mechanisms of G protein signaling and regulation. The yeast pheromone pathway has also been developed as a heterologous expression system to identify the potential agonists and antigonists for a receptor (Mentesana et al., 2002; Xue et al., 2008b).

In the basidiomycete C. neoformans, three G protein α submits control two major G protein-signaling pathways that are important for cell development and fungal virulence. One Gα protein, Gpa1, activates the nutrient sensing pathway by regulating the activity of protein kinase A (PKA) and controls fungal virulence (Alspaugh et al., 1997; Xue et al., 2008a). The receptors for activating this nutrient signaling pathway remain to be understood even though one GPCR, Gpr4, has been found to be involved in this activation, probable by sensing amino acids (Xue et al., 2006). Two other Gα subunits, Gpa2 and Gpa3, are both involved in the pheromone sensing pathway in C. neoformans. C. neoformans has a defined sexual cycle and a simple bipolar mating system (a and α) in which a single mating-type (MAT) locus spans an approximately 120 kb recombinationally-suppressed region (Hull et al., 2002). Only a-factor-like lipopeptide pheromones and Ste3-like pheromone receptors are known in C. neoformans, neither an α-like pheromone gene nor a Ste2-like ortholog is apparent in any of sequenced genomes. Pheromone receptors Ste3α and Ste3a are encoded in the MAT locus and sense pheromones from cells of the opposite mating type and activate a G-protein complex that includes Gpa2 and Gpa3, the Gβ subunit Gbp1, and the Gγ subunits Gpg1 and Gpg2 (Hsueh et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007). Following activation of Gpa2 and Gpa3, the Gβ subunits Gbp1 is released to activate the downstream MAPK cascade to trigger mating responses.

2.2. Identification of Cpr2 protein

A Ste3-like protein (CNAG_03938) was identified in our search for potential GPCR proteins in C. neoformans H99 genome, and was named as Cpr2 (Cryptococcus Pheromone Receptor 2) (Hsueh et al., 2009). Cpr2 contains 414 amino acids and 7 predicted transmembrane domains (TMs), a structural hallmark of GPCRs. The MAT locus of C. neoformans has been extensively studied and among 20 or so genes encoded by this locus, the homeodomain proteins and the pheromone/pheromone receptor genes establish the sexual identity of a cell (Chung et al., 2002; Hull et al., 2005). Interestingly, Cpr2 is not located in the MAT locus. A search for Ste3-like receptors in other basidiomyceteous fungi revealed that many species also have additional pheromone receptor paralogs that are not part of MAT (Aimi et al., 2005; James et al., 2006), suggesting basidiomyceteous fungi may have an additional mechanism for pheromone sensing and regulation.

Functional studies revealed that Cpr2 expression is regulated by pheromone and highly induced during mating. A strain carrying a deletion mutation of CPR2 is still fertile but has a defect in cell fusion. However, overexpression of CPR2 elicits unisexual mating (Hsueh et al., 2009). To understand whether this protein functions as a pheromone sensor, we expressed CPR2 gene in a yeast heterologous expression system.

2.3. Expression of CPR2 in a yeast heterologous expression system

In order to better understand the function of GPCRs, researchers attempt to express the proteins in less sophisticated organisms. Even though GPCRs in fungi have not yet been developed as drug targets for disease control, GPCR-related signaling pathways have been utilized to de-orphanize GPCRs (Mentesana et al., 2002). A bioassay based on the S. cerevisiae pheromone response pathway has been developed to characterize heterologous GPCRs. However, several preconditions must be met to utilize this pathway. First, proper plasma membrane expression of the target GPCR is needed; second, the foreign receptor must properly couple to the Gα protein Gpa1 to activate the downstream signal; third, a reporter gene in this pathway is needed to monitor GPCR expression and signal activation. Finally, the pathway needs to be optimized to enhance signal sensitivity.

Some foreign GPCR genes can be directly expressed in S. cerevisiae and coupled to the Gpa1 G protein to activate the yeast pheromone responsive pathway, including some pheromone receptors from S. commune (Fowler et al., 1999), the mammalian SSTR2 receptor (Price et al., 1995), the adenosine A2 receptor (Price et al., 1996), the melatonin Mel1a receptor (Kokkola et al., 1998), and the UDP-glucose receptor (Chambers et al., 2000). We also expressed the C. neoformans CPR2 gene in this Saccharomyces heterologous system to identify its potential ligands (Hsueh et al., 2009).

2.3.1 Establishment of the yeast heterologous expression system

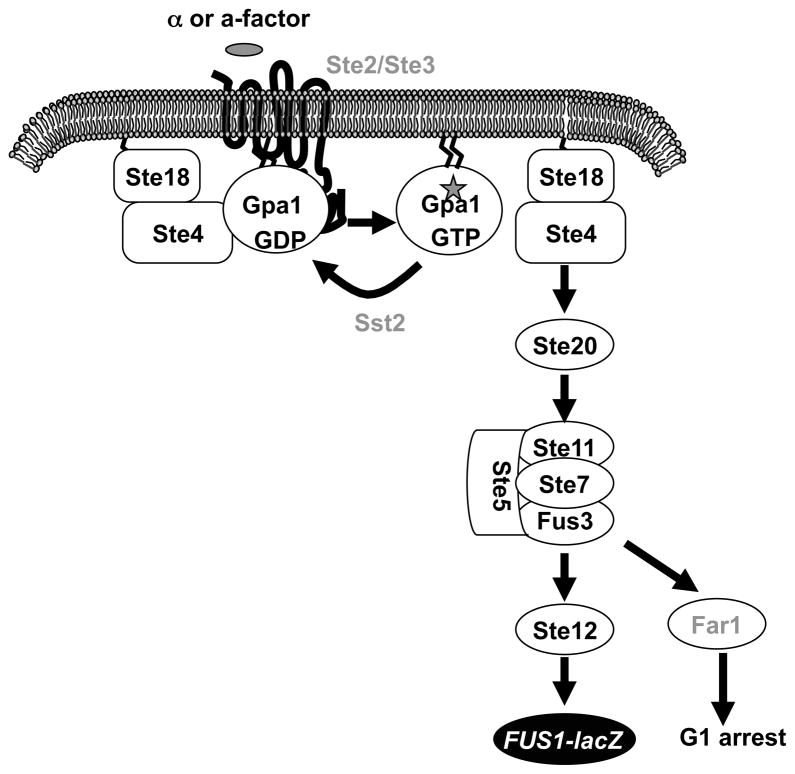

To engineer the S. cerevisiae pheromone response pathway as a heterologous expression system, several modifications are necessary to optimize signal output. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Far1 promotes yeast cell arrest in G1 in response to pheromone (Chang and Herskowitz, 1990), and FAR1 is deleted to allow continued cell division in cells responding to pheromone or a heterologous ligand. The regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) Sst2 functions as a negative regulator of Gpa1 activity and deletion of SST2 significantly increases the sensitivity of pheromone response (Dietzel and Kurjan, 1987) and the yeast heterologous GPCR expression signal. To monitor the pheromone response signal for large scale screens, the pheromone inducible gene FUS1 (Hagen et al., 1991) is commonly fused with either the lacZ gene or the HIS3 gene. Finally, to avoid interference by the endogenous receptors, the yeast pheromone receptor gene STE2 or STE3 is deleted (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The yeast pheromone responsive pathway and generation of the yeast heterologous expression system. The pheromone receptor, Ste2 or Ste3, activates the Gα protein Gpa1 by converting GDP-bound to GTP-bound and promoting the release of the Gβγ subunits (Ste4 and Ste18) from the heterotrimeric G protein complex. Ste4 in turn activates PAK kinase Ste20, and MAP kinase cascade including MAPKKK (Ste11), MAPKK (Ste7), and MAPK (Fus3). The activation of transcription factor Ste12 by Fus3 promotes mating. To generate a yeast heterologous system for Cpr2 using this signaling pathway, the pheromone receptor Ste3 is deleted to eliminate signal interference by endogenous receptor. The RGS protein Sst2 and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Far1 are deleted to optimize the signal readout. The promoter of the pheromone inducible gene FUS1 is fused with a reporter gene, such as lacZ or HIS3 to quantitatively measure the pheromone response signal. In the Cpr2 study, the lacZ gene was used.

Required materials

Vectors and strains used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Plasmids and strains used for Cpr2 assessment

| Strains | Genotype | References |

|---|---|---|

| W303-1A | MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp-1 ura3-1 can1-100 | Fowler et al., 1999 |

| W303-1B | MATα ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp-1 ura3-1 can1-100 | Fowler et al., 1999 |

| SDK45 |

MATα ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp-1 ura3-1 can1-100 ste3::ADE2 |

Fowler et al., 1999 |

| SDK47 |

MATα ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp-1 ura3-1 can1-100 ste3::ADE2 sst2::LEU2 |

Fowler et al., 1999 |

| YDX4 |

MATα ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp-1 ura3-1 can1-100 ste3::ADE2 sst2::LEU2 far1::HYG |

This study |

| YDX10 |

MATα ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp-1 ura3-1 can1-100 ste3::ADE2 sst2::LEU2 far1::HYG FUS1-lacZ-TRP |

This study |

|

| ||

| Plasmids | Description | References |

|

| ||

| pTCFL1 | FUS1::lacZ TRP1 AmpR | Chen and Kurjan, 1997 |

| pPGK | Yeast overexpression vector, PGK promoter URA3 AmpR | Kang et al., 1990 |

| pYH58 | pPGK::CPR2 cDNA URA3 AmpR | Hsueh et al., 2009 |

| pYH59 | pPGK::CPR2L222PcDNA URA3 AmpR | Hsueh et al., 2009 |

Vectors

pTCFL1 is a S. cerevisiae expression vector that contains a FUS1-lacZ fusion (Chen and Kurjan, 1997). When the pheromone responsive pathway is activated, the FUS1-lacZ fusion will express and beta-galactosidase activity can be measured. pPGK is a S. cerevisiae overexpression vector that contains the yeast phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promotor (Kang et al., 1990).

S. cerevisiae strains

W303-1A (MATa) and W303-1B (MATα) are laboratory strains used in this assay. SDK45 was generated based on W303-1B by deleting pheromone receptor STE3, and SDK47 was generated based on SDK45 by further deleting RGS gene SST2 (Fowler et al., 1999). The FAR1 gene was mutated in SDK47 to generate YDX4.

Media

YPD rich medium, SD-Trp, and SD-Trp-Ura drop out media were prepared as described (Amberg et al., 2005). To prepare 200 ml of 5x Z-buffer, 16.1 g Na2HPO4.7H2O, 6.23 g NaH2PO4.2H2O, 0.75 g KCl, 0.246 g MgSO4.7H2O are added and adjusted to pH 7.0, then add H2O to a total volume of 200 mL. Z-buffer should be stored at 4°C.

Chemicals

Lithium acetate (Fisher Scientific), Salmon sperm single-stranded DNA (Sigma), CPRG (chlorophenolred-β-D-galactopyranoside, CalBiochem), β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). Synthetic mating pheromones MFa and MFα (Heitman lab).

Equipment

Micro centrifuge (Qiagen), Water incubator (Fisher Scientific), Culture incubator (Sanyo), Shaker incubator (New Brunswick Scientific), Spectrometer (Bio-Rad).

Disposables

1.5 ml microfuge tubes (USA Scientific), 15 ml falcon tissue culture tubes (BD Bioscience), 50 ml centrifuge tubes (Denville), Petri dishes (Fisher Scientific), 1.5 ml curvette (VWR).

In order to utilize the yeast system, we modified the S. cerevisiae strains original provided by Dr. Thomas Fowler (Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville) using the following yeast transformation protocol. We generated a strain YDX4, in which three genes in pheromone pathway (STE3, SST2, and FAR1) were deleted to optimize signal output. The vector pTCFL1 containing a FUS1-lacZ fusion cassette was used to transform YDX4 to generate YDX10, in which the lacZ gene will be activated by pheromone response signals.

A. Protocol for Yeast transformation

Day 1: Inoculate a single yeast colony into a 5 ml YPD culture and incubate overnight (24 hr) with shaking at 30°C.

Day 2: Take out 120 μl overnight yeast culture and re-inoculate into 5 ml fresh YPD liquids and incubate for 5 hrs. After 5 hr incubation, centrifuge the culture at 2000 rpm for 3 min, and resuspend the pellet in 1 ml sterile deionized water (dH2O) and transfer cells to 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes. Centrifuge again for 10 seconds fast spin, wash pellets twice with 1 ml dH2O and wash once with 1 ml 0.1 M Lithium acetate (LiOAc). Resuspend washed pellets into 25 μl 0.1 M LiOAc. Add the following reagents to each tube: 200 ul 50% PEG (MW3640), 25 μl 1M LiOAc, 25 μl dH2O, 5 ul 10mg/ml ssDNA, < 10 μl plasmid DNA. Mix each reaction gently and incubate at 30°C for 30 min. Transfer tubes to 42°C for 15 min. Centrifuge and resuspend pellets in 100 μl dH2O and spread on selective medium, SD-Trp-Ura, for pTCFL1 and pPGK based vectors. Incubate at 30°C for 2–3 days.

Day 5: Streak out single colonies on a fresh SD-Trp-Ura plate. Typically at least three colonies should be streaked out for each transformation.

Yeast transformation is a routine technique and many modified protocols are available. We found the above protocol provided a simple method with consistent high transformation efficiency. Our experience with yeast transformation showed it is very important to not overgrow the culture after the second inoculation. Also always purify yeast colonies by re-streaking on selective medium to make sure only transformants expressing selective markers are obtained.

Upon the generation of the yeast strain, we first validated the sensitivity of the system by measuring the β-galactosidase activity (see below for protocol) for all three yeast strains, SDK45, SDK47, and YDX4. The supernatant from an overnight culture of W303-1A, which contains a-factor secreted by this MATa strain, was used as a ligand to activate the system. Strong induction of β-galactosidase activity was observed in all three strains background when native Ste3 was expressed, almost no signal was detected when the empty vector pPGK was introduced. These results indicate the system is working.

B. Protocol for measuring the beta-galactosidase activity in liquid cultures

Day 1: Start a 2 ml overnight culture in yeast dropout medium and let it grow at 30°C with shaking for about 24 hours.

Day 2: Centrifuge 1 ml of culture in a microfuge tube for about 2 second. Cell pellets were resuspended in 0.5 ml 1x Z-buffer (add 67 μl beta-mercaptoethonal, 19 μl 10% SDS, 5 ml 5x Z buffer, and 19.914 ml ddH2O to make 25 ml of 1x Z-buffer) and vortexed for 1 min at room temperature. Add 25 μl chloroform and vortex for 5 min at room temperature. Add 100 μl CPRG solution (final concentration of CPRG is 4 mM) and incubate at 28°C until red color appears (8–20 min). Record the time of incubation. Put the sample on ice for 5 min to “stop” the reaction. Spin out debris for 5 min at full speed at 4°C and transfer 500 μl to cuvette and read O.D.595 in a spectrometer. Prepare appropriate dilution for measurement if color is too intense. Also read O.D.600 for the remaining 1 ml of overnight culture (usually needs 1:5 dilution). Calculate the enzyme activity using the following formula: . At least three replicates are needed for enzyme activity quantification because of the potential variation between different replications.

This is a simple protocol to quickly determine the β-galactosidase enzyme activity. It is important to measure the absorbance quickly to obtain representative results, because the color will increase over time even when tubes are kept on ice to “stop” the reaction.

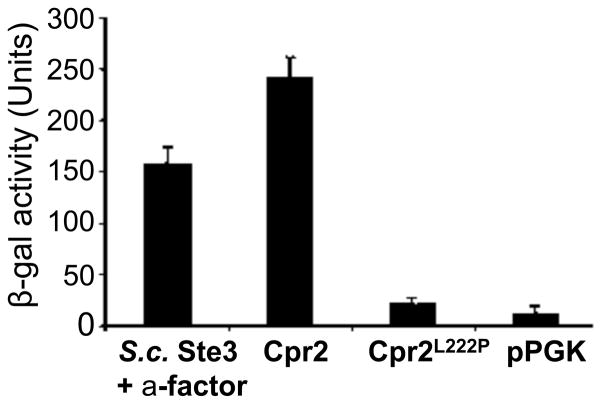

2.2.2. Assessment of constitutive activity of Cpr2 in the yeast system

The establishment of a yeast system that can be used to quantify the activity of pheromone responsive pathway by measuring the β-galactosidase activity allowed us to test the expression and activity of Cpr2 in this system. The CPR2 overexpression construct YPH58 was used to transform SD45, SDK47, and YDX4. The expression of CPR2 was confirmed by Northern blot. In this experiment, pPGK empty vector was used as a negative control and a vector expressing native Ste3 from S. cerevisiae was used as the positive control. Yeast cells expressing CPR2 and FUS1-lacZ were cultured on a yeast drop-out medium (SD-Trp-Ura) and β-galactosidase activities were measured following induction with different extracellular signals. Surprisingly, high β-galactosidase activity readouts were generated without exposing cells to putative ligands such as C. neoformans MFa or MFα synthetic pheromones (Hsueh et al., 2009) (Figure 2). Cpr2 induced high levels of β-galactosidase activity even in strain SDK45 background, which still has the wild-type SST2 and FAR1 alleles, and therefore, we have carried out the rest of the assays in strain SDK45 (Figure 2). The S. cerevisiae reporter strains SDK45, SDK47, and YDX10 are MATα; therefore, they produce only α factor, which should not act on GPCRs related to Ste3 (respond only to lipid-modified peptides).

Figure 2.

The constitutive activity of Cpr2 is dependent on the Leu222 residue based on assays in a yeast heterologous expression system. Cpr2 is heterologously expressed in SDK45 carrying the FUS1-lacZ reporter. Cells expressing S. cerevisiae Ste3 treated with yeast a-cell supernatant served as a positive control. Cells containing the empty vector pPGK served as a negative control. Cells expressing Cpr2 or Cpr2L222P were measured for the β-galactosidase activity without treatment of potential ligands. All results are based on at least three repeats. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

The highly induced β-galactosidase activity in CPR2-expressing cells suggested that Cpr2 was either activated by a ubiquitous ligand present in the culture supernatants or that Cpr2 is a constitutively active GPCR that functions in a ligand-independent manner. The further identification of a single amino acid that is responsible for the enzyme activity without additional ligands confirms that the Cpr2 wild type form is a naturally-occurring, constitutively active receptor (Hsueh et al., 2009).

2.2.3 Identification of Leu222 as the cause of constitutive activity of Cpr2

It is known that alteration of amino acid sequences in certain conserved positions in some GPCRs results in constitutively active mutants (CAMs). 90% of GPCRs contain a conserved proline in the sixth transmembrane domain (TM-VI), and substitution of this proline with leucine increases the ligand-independent activity of many GPCRs (Baldwin, 1993). CAMs have been generated using such point mutations in the pheromone receptors of S. cerevisiae (Ste2, Ste3) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Mam2) (Konopka et al., 1996; Ladds et al., 2005; Stefan et al., 1998). Surprisingly, this conserved proline is absent in the TM-VI of wild-type Cpr2, and instead, a leucine is substituted at this position Leu222. To test the possibility that this leucine in TM-VI might be responsible for the constitutive activity of Cpr2, a construct (YPH59) expressing the CPR2L222P allele was introduced in S. cerevisiae SDK45. As shown in Figure 2, ligand-independent induction of β-galactosidase activity was reduced to the basal level in cells expressing CPR2L222P, compared to the empty vector control. This result provides evidence that Cpr2 activates the pheromone response pathway via an intrinsic constitutive activity instead of responding to a ubiquitous ligand present in the culture.

Because CPR2 was overexpressed in the S. cerevisiae heterologous system, one possibility is that the overexpression might cause the constitutive activity of Cpr2. It has been reported that even some wild-type ligand-dependent GPCRs, a small fraction of the total receptor pool may exist in the active form in the absence of agonist; thus, simply overexpressing some GPCRs could elicit a constitutively active response (Milano et al., 1994). However, we do not think that overexpression alone is sufficient in the case of Cpr2-induced pheromone signaling because overexpressing either the canonical pheromone receptor Ste3α or the Cpr2L222P allele did not activate the FUS1-lacZ reporter gene in S. cerevisiae (Figure 2).

Several other lines of evidence, including phenotypic analysis of cpr2 mutants in C. neoformans, confirmed our conclusion. Overexpression of the Cpr2L222P allele in the C. neoformans ste3α mutant did not cause a hyperfilamentation phenotype as did of Cpr2 overexpression. Overexpression of Cpr2 in a C. neoformans mfα 1, 2, 3 pheromoneless mutant still conferred a hyperfilamentous phenotype, eliminating the possible involvement of an autocrine-signaling loop. In protein-protein interaction assays using a split-ubiquitin yeast two-hybrid system, only the interactions of Cpr2L222P with Gpa2 and Gpa3, but not of Cpr2 with these G proteins were detected, implying the interaction between wild type Cpr2 and the Gα subunits could be transient due to its constitutive activity (Hsueh et al., 2009).

Although in many cases, including Cpr2, substitution of proline with leucine increases constitutive activity of GPCRs, not all GPCRs become constitutively active when this proline residue is missing or mutated. The Ste3a receptor in C. neoformans is one such example, as it lacks a conserved proline in TM-VI but does not display any constitutive activity.

We have also tried to identify the potential inverse agonist agents for Cpr2 by testing the synthetic mating pheromones MFa and MFα, as well as a range of farnesol derivatives (pheromones are farnesylated) in the yeast heterologous expression system. None of these chemicals significantly altered the readout of β-galactosidase activity. Therefore, inverse agonists for Cpr2, if they exist, remain to be identified. Their existence is an intriguing hypothesis for future investigation.

2.2. 4. Limitation of the yeast heterologous expression system and alternatives

Not all GPCRs can be expressed correctly, couple with S. cerevisiae Gpa1 and activate the downstream pheromone pathway. One example is Gpr4 in C. neoformans. We cloned GPR4 in pPGK and expressed it in YDX10, but did not observed any pheromone-induced lacZ activity. So modifying the system, such as making chimeric G proteins, or chimeric GPCRs may expand the system for the analysis of other receptors that do not directly express well in yeast.

Actually, in most cases, modifications of Gpa1 or the GPCR itself are necessary to promote proper GPCR-G protein interaction and pathway activation. For example, most GPCRs couple to the C terminus of the G protein Gpa1, and one way to improve coupling between foreign receptors and Gpa1 without interfering Gpa1 activity is to generate a chimeric Gα by replacing the Gpa1 C-terminal region with the corresponding protein of the foreign Gα. Some studies indicate that replacing only 5 amino acids is sufficient to promote specific GPCR-Gα coupling (Komatsuzaki et al., 1997; Kostenis et al., 1997; Mentesana et al., 2002). We have constructed three chimeric G proteins where C-terminal 30 amino acids of S. cerevisiae Gpa1 was replaced by the corresponding C-terminal region of Gα proteins (Gpa1, Gpa2, and Gpa3) in C. neoformans, respectively. These chimeric G proteins have been successfully expressed in a yeast strain with STE3, SST2, and FAR1 all mutated (Xue et al., unpublished). Another approach that has been successfully applied is generating chimeric proteins by fusing adrenergic receptors and their cognate Gα subunits (Bertin et al., 1994; Wise et al., 1997). However, this approach is not suitable for all receptors, suggesting the mechanisms for the pathway activation may be more complex.

Modifying the receptor itself is another way to improve foreign receptor expression and signal activation in yeast. Foreign GPCRs fused with the cytoplasmic domain of the Ste2 or Ste3 pheromone receptor serve to enforce coupling between receptor and Gpa1 (King et al., 1990). This approach is particularly useful for GPCRs with unknown cognate Gα subunits (Yin et al., 2004).

As an alternative, there are other systems available to serve similar purposes. In the fission yeast S. pombe, the GPCR Stm1 has been identified as a nutrient sensor. Overexpression of STM1 promotes uncontrolled cell division of yeast cells, which triggers a severe growth defect and also conversion of diploid to haploid cells (Chung et al., 2003). This phenotype has been successfully utilized for high throughput screens of Stm1 inhibitors. Chemical compounds were applied to an STM1 overexpression strain and inhibitors of Stm1 rescued the growth defect of the test strain (Chung et al., 2007). Because Stm1 interacts with the G protein Gpa2 to exert its effect on cell growth (Chung et al., 2003), this system can also be used to test heterologous GPCRs for their interactions with Gpa2 and screen for potential modulators.

3. Additional constitutively active receptors identified in fungi

Although no naturally-occurring constitutively active GPCR has been reported in ascomycetes, mutagenesis has been used to introduce mutant receptors with constitutive activity. The pheromone receptor Ste2 has been most thoroughly studied to identify amino acids important for function. Both site-direct mutagenesis and PCR-derived random mutagenesis approaches have been applied to select point mutations that cause the receptor to be constitutively active or dominantly negative (Konopka et al., 1996; Lee et al., 2006; Sommers et al., 2000). A number of sites in Ste2 have been identified as critical for ligand binding and protein function using these approaches. Also in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, a constitutively active mutant of P-factor receptor Mam2 (P262L) has also been reported (Ladds et al., 2005)

Many basidiomyceteous fungi, such as mushrooms, contain multiple sexes controlled by many different pheromone receptors. For example, in the mushroom Coprinus cinereus, the multiallelic B mating type genes encode a large family of seven-transmembrane domain receptors and CaaX-modified pheromones. According to results obtained using a yeast heterologous expression assay, the C. cinereus pheromone receptor acts as a G protein-coupled receptor and self-compatible mutations cause its constitutive activation (Olesnicky et al., 1999). In the laboratory, two TM-VI mutations of pheromone receptors in Schizophyllum commune have been identified to produce constitutive receptor activity (Tom Fowler, personal communication). Similar to Cpr2, many of these receptors are not located in the MAT locus. It is possible that naturally occurring constitutively active receptors may exist to regulate the pheromone sensing response in other fungi. Thus, the methods used to assess constitutive activity of Cpr2 will be beneficial for the studies of other potential constitutively active receptors and their mutants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joe Heitman, Carol Newlon, and Tom Fowler for critical reading and comments on the manuscript, Tom Fowler and James Konopka for S. cerevisiae strains and vectors. The original research on Cpr2 functional study was supported by National Institute of Health R21 grant (AI070230) to Joe Heitman. This work was supported by the new PI institutional start-up fund from UMDNJ to C.X.

References

- Aimi T, et al. Identification and linkage mapping of the genes for the putative homeodomain protein (hox1) and the putative pheromone receptor protein homologue (rcb1) in a bipolar basidiomycetePholiota nameko. Curr Genet. 2005;48:184–94. doi: 10.1007/s00294-005-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alspaugh JA, et al. Cryptococcus neoformans mating and virulence are regulated by the G-protein alpha subunit GPA1 and cAMP. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3206–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg DC, et al. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor laboratory Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bahn YS, et al. Sensing the environment: lessons from fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JM. The probable arrangement of the helices in G protein-coupled receptors. EMBO J. 1993;12:1693–703. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin B, et al. Cellular signaling by an agonist-activated receptor/Gs alpha fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8827–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J, Pin JP. Molecular tinkering of G protein-coupled receptors: an evolutionary success. EMBO J. 1999;18:1723–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder AC, Hartwell LH. The yeast alpha-factor receptor: structural properties deduced from the sequence of the STE2 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:8463–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.23.8463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerione RA, et al. The mammalian beta 2-adrenergic receptor: reconstitution of functional interactions between pure receptor and pure stimulatory nucleotide binding protein of the adenylate cyclase system. Biochemistry. 1984;23:4519–25. doi: 10.1021/bi00315a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JK, et al. A G protein-coupled receptor for UDP-glucose. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10767–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F, Herskowitz I. Identification of a gene necessary for cell cycle arrest by a negative growth factor of yeast: FAR1 is an inhibitor of a G1 cyclinCLN2. Cell. 1990;63:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Kurjan J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mpt5p interacts with Sst2p and plays roles in pheromone sensitivity and recovery from pheromone arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3429–39. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KS, et al. Functional over-expression of the Stm1 protein, a G-protein-coupled receptor, in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Biotechnol Lett. 2003;25:267–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1022355102192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KS, et al. Yeast-based screening to identify modulators of G-protein signaling using uncontrolled cell division cycle by overexpression of Stm1. J Biotechnol. 2007;129:547–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, et al. Molecular analysis of CPRalpha, a MATalpha-specific pheromone receptor gene of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2002;1:432–9. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.3.432-439.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel C, Kurjan J. Pheromonal regulation and sequence of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SST2 gene: a model for desensitization to pheromone. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4169–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.12.4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews J. Genomic sciences and the medicine of tomorrow. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1516–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1196-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler TJ, et al. Multiple sex pheromones and receptors of a mushroom-producing fungus elicit mating in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2559–72. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.8.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen DC, et al. Evidence the yeast STE3 gene encodes a receptor for the peptide pheromone a factor: gene sequence and implications for the structure of the presumed receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:1418–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen DC, et al. Pheromone response elements are necessary and sufficient for basal and pheromone-induced transcription of the FUS1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2952–61. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harashima T, Heitman J. Nutrient control of dimorphic growth inSaccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Winderickx J, Taylor PM, editors. Nutrient induced responses in eukaryotic cells. Vol. 7. Springer-Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 2004. pp. 131–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP, et al. G protein signaling governing cell fate decisions involves opposing Galpha subunits in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3237–49. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh YP, et al. A constitutively active GPCR governs morphogenic transitions in Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO J. 2009;28:1220–33. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull CM, et al. Sex-specific homeodomain proteins Sxi1alpha and Sxi2a coordinately regulate sexual development in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:526–35. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.3.526-535.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull CM, et al. Cell identity and sexual development in Cryptococcus neoformans are controlled by the mating-type-specific homeodomain protein Sxi1alpha. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3046–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.1041402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James TY, et al. Evolution of the bipolar mating system of the mushroom Coprinellus disseminatus from its tetrapolar ancestors involves loss of mating-type-specific pheromone receptor function. Genetics. 2006;172:1877–91. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.051128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YS, et al. Effects of expression of mammalian G alpha and hybrid mammalian-yeast G alpha proteins on the yeast pheromone response signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2582–90. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.6.2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King K, et al. Control of yeast mating signal transduction by a mammalian beta 2-adrenergic receptor and Gs alpha subunit. Science. 1990;250:121–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2171146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkola T, et al. Mutagenesis of human Mel1a melatonin receptor expressed in yeast reveals domains important for receptor function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:531–6. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsuzaki K, et al. A novel system that reports the G-proteins linked to a given receptor: a study of type 3 somatostatin receptor. FEBS Lett. 1997;406:165–70. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka JB, et al. Mutation of Pro-258 in transmembrane domain 6 constitutively activates the G protein-coupled alpha-factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6764–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski G, et al. Modulation of sodium-sensitive GTPase by partial opiate agonists. An explanation for the dual requirement for Na+ and GTP in inhibitory regulation of adenylate cyclase. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14035–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostenis E, et al. Genetic analysis of receptor-Galphaq coupling selectivity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23675–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraakman L, et al. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae G-protein coupled receptor, Gpr1, is specifically required for glucose activation of the cAMP pathway during the transition to growth on glucose. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1002–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladds G, et al. A constitutively active GPCR retains its G protein specificity and the ability to form dimers. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:482–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, et al. Interacting residues in an activated state of a G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2263–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengeler KB, et al. Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:746–85. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.4.746-785.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, et al. Canonical heterotrimeric G proteins regulating mating and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4201–9. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentesana PE, et al. Functional assays for mammalian G-protein-coupled receptors in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002;344:92–111. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)44708-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano CA, et al. Enhanced myocardial function in transgenic mice overexpressing the beta 2-adrenergic receptor. Science. 1994;264:582–6. doi: 10.1126/science.8160017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesnicky NS, et al. A constitutively active G-protein-coupled receptor causes mating self-compatibility in the mushroom Coprinus. EMBO J. 1999;18:2756–63. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price LA, et al. Functional coupling of a mammalian somatostatin receptor to the yeast pheromone response pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6188–95. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price LA, et al. Pharmacological characterization of the rat A2a adenosine receptor functionally coupled to the yeast pheromone response pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:829–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkilde MM, et al. Molecular pharmacological phenotyping of EBI2. An orphan seven-transmembrane receptor with constitutive activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13199–208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert R, Wenzel-Seifert K. Constitutive activity of G-protein-coupled receptors: cause of disease and common property of wild-type receptors. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:381–416. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers CM, et al. A limited spectrum of mutations causes constitutive activation of the yeast alpha-factor receptor. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6898–909. doi: 10.1021/bi992616a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan CJ, et al. Mechanisms governing the activation and trafficking of yeast G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:885–99. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sande J, et al. Somatic and germline mutations of the TSH receptor gene in thyroid diseases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2577–85. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.9.7673398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A, et al. Measurement of agonist efficacy using an alpha2A-adrenoceptor-Gi1alpha fusion protein. FEBS Lett. 1997;419:141–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue C, et al. G protein-coupled receptor Gpr4 senses amino acids and activates the cAMP-PKA pathway in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:667–79. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue C, et al. The RGS protein Crg2 regulates both pheromone and cAMP signalling in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol Microbiol. 2008a;70:379–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue C, et al. Magnificent seven: roles of G protein-coupled receptors in extracellular sensing in fungi. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008b;32:1010–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D, et al. Probing receptor structure/function with chimeric G-protein-coupled receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1323–32. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]