Abstract

Objective To characterise the complete case series of influenza A/H7N9 infections as of 27 May 2013, detected by China’s national sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness.

Design Case series.

Setting Outpatient clinics and emergency departments of 554 sentinel hospitals across 31 provinces in mainland China.

Cases Infected individuals were identified through cross-referencing people who had laboratory confirmed A/H7N9 infection with people detected by the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness, where patients meeting the World Health Organization’s definition of influenza-like illness undergo weekly surveillance, and 10-15 nasopharyngeal swabs are collected each week from a subset of patients with influenza-like illness in each hospital for virological testing. We extracted relevant epidemiological data from public health investigations by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at the local, provincial, and national level; and clinical and laboratory data from chart review.

Main outcome measure Epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory profiles of the case series.

Results Of 130 people with laboratory confirmed A/H7N9 infection as of 27 May 2013, five (4%) were detected through the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness. Mean age was 13 years (range 2-26), and none had any underlying medical conditions. Exposure history, geographical location, and timing of symptom onset of these five patients were otherwise similar to the general cohort of laboratory confirmed cases so far. Only two of the five patients needed hospitalisation, and all five had mild or moderate disease with an uneventful course of recovery.

Conclusion Our findings support the existence of a “clinical iceberg” phenomenon in influenza A/H7N9 infections, and reinforce the need for vigilance to the diverse presentation that can be associated with A/H7N9 infection. At the public health level, indirect evidence suggests a substantial proportion of mild disease in A/H7N9 infections.

Introduction

A common feature of influenza disease is the “clinical iceberg” phenomenon, which states that many mild cases of infection escape clinical detection owing to the lack of severe symptoms presented.1 This phenomenon is certainly true for interpandemic influenza2 as well as for the influenza A/H1N1 pandemic in 2009.3 However, A/H5N1 is an acknowledged exception,4 whereas the A/H7N7 outbreak in the Netherlands suggested that there was a large submerged portion of the iceberg, but which was not as substantial as that for other interpandemic human strains.5 6

The influenza A/H7N9 virus emerged in early 2013, and people with infections initially confirmed in the laboratory were admitted to hospital with serious illness.7 8 Most laboratory confirmed infections have been found in residents of urban areas, who have reported recent exposure to live poultry,9 10 and investigations of live poultry markets have identified a high prevalence of influenza A/H7N9 virus in poultry.11 However, comparison of the incidence of laboratory confirmed cases with patterns in exposure suggests that seriousness of infection may increase with age, and that some mild infections may have gone undetected in younger adults.12 13 In addition, a small number of laboratory confirmed cases have been identified through China’s national sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness.14

Here, we describe the clinical characteristics of all patients with A/H7N9 infections as of 27 May 2013, who were identified through routine testing by the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness. These findings could indicate the sizable proportion of people with milder infections and who would otherwise not have been detected, which would be important if present circulating strains of A/H7N9 were to acquire the ability to spread efficiently among humans. Moreover, there is an urgent need to better understand how these patients may present at the clinical interface, and if they represent a separately identifiable group. The objective of our study was to characterise the complete case series of A/H7N9 infections as of 27 May 2013, identified through China’s national sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness.

Methods

Sources of cases

All laboratory confirmed A/H7N9 infections are reported to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention through a national sentinel surveillance system. Case definitions, surveillance for identification of A/H7N9 cases, and laboratory test assays have been described in a previous report.9 A joint field investigation team—comprising staff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at the local, provincial, and national level—conducted field investigations of the laboratory confirmed cases of A/H7N9 virus infection.

Surveillance of influenza-like illness in China

Surveillance of influenza-like illness and its associated virology in China is conducted through a national sentinel network across the country. The network consists of outpatient clinics and emergency departments of 554 sentinel hospitals across 31 provinces in mainland China, covering 2.5% of all hospitals in China. Data for cases of influenza-like illness included the total number of outpatient or emergency department visits, and the number of patients fitting the World Health Organization’s standard case definition of influenza-like illness (that is, body temperature ≥38°C with either a cough or sore throat in the absence of an alternative diagnosis) is reported on a weekly basis through a centralised online system to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

For each sentinel site, 10-15 nasopharyngeal swabs are collected each week by convenience samples of patients with influenza-like illness who had not taken antiviral drugs and who had fever (>38°C) for no longer than three days. These swabs undergo routine virological testing and subtyping, and results are reported to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention within 24 h.15 Surveillance is conducted throughout the year to systematically collect data all year round with a consistent sampling frame. Outpatient clinics or emergency departments in hospitals represent a typical first step for patients with influenza-like illness in China to present to the healthcare system, owing to the coverage of national health insurance programmes and the lack of standalone primary healthcare clinics in either the public or private sector as an alternative. Although the selection of patients with influenza-like illness for virology testing was not random, there should not have been any incentive for selection according to clinical severity, because results would not have been fed back to doctors for treatment purposes. Therefore, the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness is believed to capture typical patients in the community, and thought to give a representative picture of the disease in China.

By cross-referencing the laboratory confirmed cases of A/H7N9 infection with patients detected by the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness, we could identify all infected patients detected through the surveillance system as of 27 May 2013. We extracted demographic and epidemiological data from public health investigations by the local, provincial, and national level Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and clinical and laboratory data from chart review.

Results

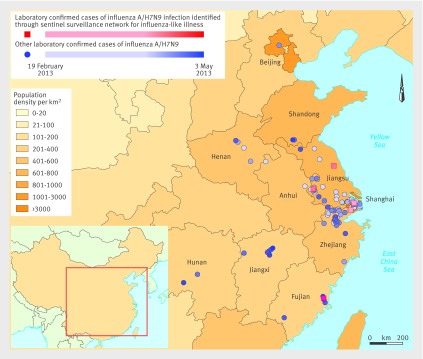

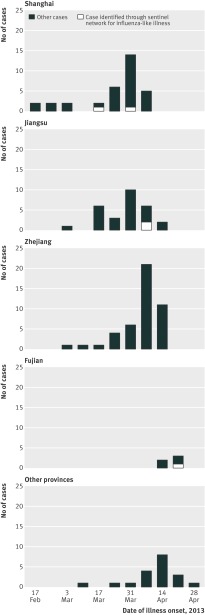

Among the 130 laboratory confirmed cases of A/H7N9 infection as of 27 May 2013, five patients were first identified through the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness. The earliest laboratory confirmed cases occurred in the Yangtze River Delta, and more recent cases were detected to the north and south. Figure 1 shows the geographical location of 130 confirmed cases, and the five cases detected through sentinel surveillance. Figure 2 shows the timing of illness onset in those five cases compared with the other laboratory confirmed cases in affected provinces.

Fig 1 Distribution of laboratory confirmed cases of influenza A/H7N9 virus infection in mainland China, by location, between 19 February and 3 May 2013. Red squares=five cases detected through the sentinel surveillance system; blue circles=all other cases. Provinces are shaded according to population density, and A/H7N9 cases with more recent calendar dates of illness onset are represented by symbols with darker shades

Fig 2 Distribution of laboratory confirmed cases of influenza A/H7N9 virus infection in mainland China, by time. Number of cases by calendar date of illness onset in Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, and other provinces

Clinical characteristics

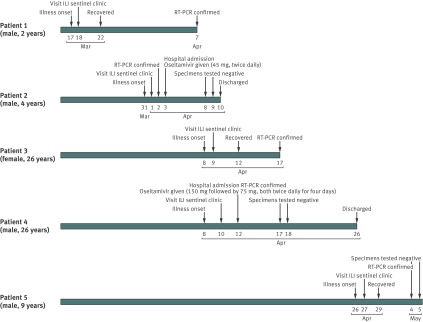

The five patients identified by the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness (patients 1-5) ranged in age from 2 to 26 years (mean 13 years), of whom four (80%) were male. They lived in urban areas of three different provinces. Date of symptom onset ranged from 17 March to 26 April 2013. Three patients were young children, and four had a confirmed history of exposure to live animals, including chickens. All presented with fever, and most with upper respiratory tract symptoms. Four were captured by the surveillance system within the next day, and one within two days of symptom onset. All five patients had mild to moderate disease and have since recovered. Among them, three (60%) were managed only as outpatients, and the other two (40%) were admitted to hospital and subsequently discharged. One patient had pneumonia without requiring intensive care. All close contacts of these five patients underwent medical surveillance and had remained well. Figure 3 summarises key clinical milestones of each patient, and table 1 shows their epidemiological characteristics.

Fig 3 Clinical milestones of patients 1-5 detected through routine sentinel surveillance for influenza-like illness in China. RT-PCR=reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of five patients with influenza A/H7N9 identified through routine surveillance for influenza-like illness in China

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 2 | 4 | 26 | 26 | 9 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Male | Male |

| Location | Shanghai | Shanghai | Jiangsu | Jiangsu | Fujian |

| Residential setting | Urban | Urban | Urban | Urban | Urban |

| Underlying medical conditions | None | None | None | None | None |

| Type of exposure | Data unavailable | Poultry exposure around the home | Exposure to pigeon | Work place close to live poultry market | Poultry exposure around the home |

| No of close contacts traced | 9 | 18 | 5 | 21 | Data unavailable |

| Date of illness onset | 17 March 2013 | 31 March 2013 | 8 April 2013 | 8 April 2013 | 26 April 2013 |

| Presenting symptoms | Fever | Fever, rhinorrhoea | Fever, myalgia | Fever, productive cough | Fever, diarrhoea, malaise |

| Pneumonia (as indicated by lung consolidation on chest radiograph) | No | No | No | Yes (left sided) | No |

| Mechanical ventilation | No | No | No | No | No |

| Time from illness onset to clinical milestone | |||||

| First visit at any medical facility (days) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Visit to surveillance sentinel clinic (days) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Admission to hospital (days) | Never admitted | 3 | Never admitted | 4 | Never admitted |

| Receiving antiviral treatment (days) | Not treated with antiviral drugs | 3 | Not treated with antiviral drugs | 4 | Not treated with antiviral drugs |

| Recovery or hospital discharge (days) | 5 | 10 (hospital discharge) | 4 | 18 (hospital discharge) | 3 |

Patient 1 was a 2 year old child from Shanghai, patient 3 was a 26 year old woman from Jiangsu, and patient 5 was a 9 year old primary school student from Fujian. Patients 3 and 5 had a history of poultry exposure. They all presented with fever and were seen within one day of symptom onset in a designated site of the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness. Nasopharyngeal swabs were taken, as part of the 10-15 routine samples per week for virological surveillance. Because patients 1, 3, and 5 all had a mild presentation, they were not suspected to have been infected by A/H7N9 and were managed as outpatients without antiviral prescription. All three patients quickly recovered after 3-5 days. Nasopharyngeal swabs collected at the first visit to the ILI sentinel clinics for all three patients were tested positive for A/H7N9 after their full recovery.

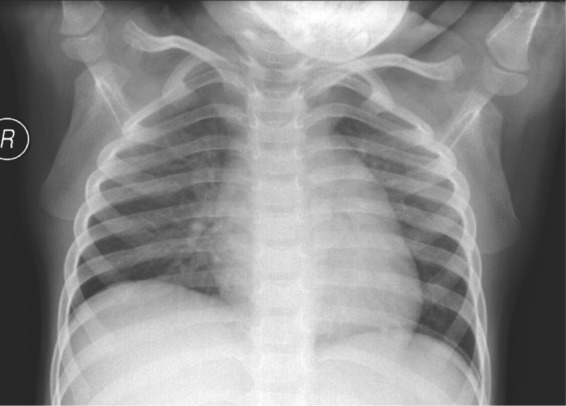

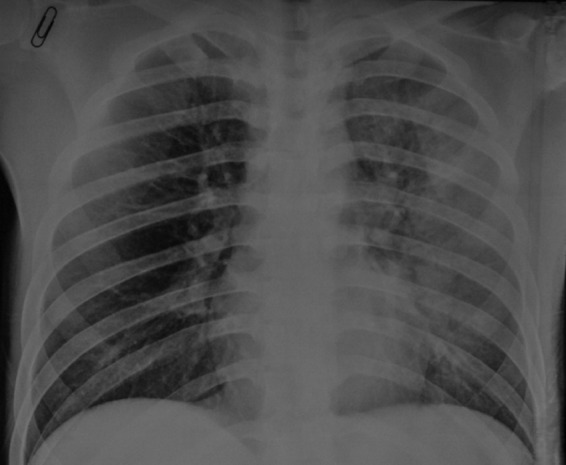

Patient 2 was a 4 year old child from Shanghai, who developed a fever of 39°C and mild rhinorrhoea on 31 March 2013, and was seen in a routine sentinel clinic on 1 April, where a nasopharyngeal swab taken. He was admitted to hospital on 3 April when the swab tested positive for A/H7N9, and was started on oseltamivir 45 mg twice daily for five days. His chest radiograph on admission (fig 4) and other laboratory findings showed no abnormalities (table 2). He remained clinically stable, and his symptoms quickly resolved. When two consecutive nasopharyngeal samples tested negative on 8 and 9 April, he was discharged on 10 April.

Fig 4 Radiological findings of patient 2 with influenza A/H7N9 infection, identified through routine sentinel surveillance for influenza-like illness in China

Table 2.

Laboratory and treatment characteristics of patients 2 and 4 with influenza A/H7N9 identified through routine surveillance for influenza-like illness in China

| Patient 2 (mild infection) | Patient 4 (moderate infection) | |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory findings | ||

| White blood cell count (109 cells/L) | 6.2 | 5.9 |

| Neutrophils (109 cells/L) | 2.6 | 3.2 |

| Lymphocytes (109 cells /L) | 3.0 | 2.4 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 114 | 186 |

| Platelets (109 cells /L) | 279 | 129 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L)* | 9 | 63 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L)* | 24 | 87 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 25.0 | 49.9 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L)* | 31.0 | 605.8 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L)* | 223 | 1849 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 149 | 133.8 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | Test not done | Test not done |

| C reactive protein (nmol/L) | 8.0 | Test not done |

| Fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) | Test not done | 0.3 |

| Arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2; mm Hg)† | Test not done | 62.0 |

| Arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2, mm Hg)† | Test not done | 42.0 |

| PaO2:FiO2 ratio | Test not done | 206.7 |

| Treatment | ||

| Antiviral drugs | Oseltamivir (45 mg, twice daily for 5 days) | Oseltamivir (150 mg, twice daily for 4 days; then 75 mg, twice daily for 4 days) |

| Steroids | No | No |

| Antibiotics | No | Ceftazidime (1 g, once every 6 h for 3 days); then moxifloxacin (400 mg, daily for 2 days) |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin | No | No |

*1 U/L=0.0167 µkat/L.

†1 mm Hg=0.133 kPa.

Patient 4 was a 26 year old man from Jiangsu who first had fever and a productive cough with yellowish sputum on 8 April. He sought care at a routine sentinel clinic two days later, and was prescribed 1 g ceftazidime every 6 h. He presented again on April 12 with fever of 38.5°C, and was admitted to hospital and started on oseltamivir 75 mg twice daily and moxifloxacin 400 mg once daily. Initial investigation revealed radiological evidence of left sided pneumonia (fig 5) and mildly elevated concentrations of serum transaminases (table 2). His nasopharygeal swab at the sentinel clinic tested positive for A/H7N9 after his admission. He improved clinically and was discharged on 26 April 2013.

Fig 5 Radiological findings of patient 4 with influenza A/H7N9 infection, identified through routine sentinel surveillance for influenza-like illness in China. Chest radiograph on admission shows ground glass opacity at upper and middle lung fields on patient’s left side

Discussion

Summary and clinical implications of results

The complete case series of A/H7N9 infections detected to date through China’s national sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness has provided contrasting clinical presentations to the generally more severe presentations of A/H7N9 cases reported so far.7 9 The five patients detected by the surveillance system were much younger, on average, than the cohort of people with laboratory confirmed infections (13 years v about 60 years). But both groups otherwise shared similar epidemiological characteristics—including exposure history, geographical location, and calendar time of disease onset. However, none of the five patients had any chronic underlying medical conditions, unlike many in the general cohort of confirmed cases.7 9 16 Our report expands on a preliminary assessment of six people with A/H7N9 infections who were identified either through the routine sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness or through enhanced surveillance among inpatients with atypical pneumonia, established as part of the response to A/H7N9.14 17

Our findings reinforce the need for vigilance to the diverse presentation that can be associated with A/H7N9 infection. This vigilance is important not only in the interest of direct patient care, but also in terms of public health, because a large proportion of unidentified cases with mild infection in the community may be a source of infection to other susceptible people if A/H7N9 develops the capacity for human to human transmission, thus making an epidemic potentially much more difficult to control.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Because five (4%) of the 130 patients with laboratory confirmed infections presented with mild disease and were detected only by the sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness, our findings provide indirect evidence of a substantial proportion of mild disease. This proportion would be in keeping with most influenza strains, with the notable exception of A/H5N1, to varying degrees. Systematic seroepidemiology studies will provide definitive evidence in time, by use of a cross-sectional design and by longitudinal paired sampling. In the interim, however, formal techniques for statistical inference can give bounded estimates to inform real time decision making in public health. Additionally, any simple computation of the “confirmed case fatality risk”—that is, dividing the number of deaths by the total number of laboratory confirmed and reported cases—could be complicated by a denominator that is probably much larger (as these results suggest), thus upward biasing the projection of mortality burden in the population.

At the system level, although sentinel surveillance systems for influenza-like illness are primarily designed for informing situational awareness rather than actual case finding in an epidemic setting,1 our results suggest that large scale surveillance networks in the community can be useful as a population based sampling tool to enhance understanding of the full spectrum of disease, especially in the early phase of an evolving epidemic such as the present one.

Importantly, this report is limited by the lack of associated viral genetic data. Future work should investigate any potential divergence in viral characteristics by phylogenetic and deep sequencing analysis between cases detected by various different routes—that is, routine surveillance for influenza-like illness versus direct clinical presentation otherwise.

What is already known on this topic

The “clinical iceberg” phenomenon of milder cases that escape detection is a common feature of influenza

Most reports of infection from the novel influenza A/H7N9 virus have so far presented a severe clinical picture

It remains unknown whether the clinical iceberg phenomenon applies to A/H7N9

What this study adds

Evidence suggests that there is an important proportion of mild disease, and supports the existence of a clinical iceberg phenomenon in influenza A/H7N9 infections

Our findings reinforce the need for vigilance to the diverse presentation that can be associated with influenza A/H7N9 infections

We thank staff members of the Bureau of Disease Control and Prevention, Health Emergency Response Office of the National Health and Family Planning Commission, and provincial and local departments of health for assisting with administration and data collection; staff members at county, prefecture, and provincial government offices, and at the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention in Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Henan, Beijing, Shandong, Jiangxi, Fujian, and Hunan provinces for assisting with the field investigation, administration, and data collection.

Contributors: GML and HY conceptualised the study design and supervised the study. QL, ZG, BC, LF, XX, HJ, ML, JB, JZ, QZ, ZC, YL, JY, FL, WY, and HY acquired the data. DKMI, QL, PW, MYN, GML, and HY analysed and interpreted the data. DKMI and PW drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised and approved the final manuscript. DKMI, QL, PW, ZG, and BC contributed equally to this work. GML and HY are guarantors.

Funding: This study received funding from the US National Institutes of Health (Comprehensive International Program for Research on AIDS grant U19 AI51915); the China-US collaborative program on emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. The study was also funded by grants from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2012 ZX10004-201); the Harvard Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant U54 GM088558); the Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Disease, Food, and Health Bureau (government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region), and the area of excellence scheme of the Hong Kong University grants committee (grant AoE/M-12/06). The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to publish.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that: support from the US National Institutes of Health, China-US collaborative program on emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Harvard Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, and Hong Kong University for the submitted work; DKMI has received research funding from Hoffmann-La Roche; BJC has received research funding from MedImmune, and consults for Crucell NV; GML has received speaker honorariums from HSBC and Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The National Health and Family Planning Commission of China determined that the collection of data from A/H7N9 cases was part of a continuing public health investigation of an emerging outbreak and was exempt from institutional review board assessment.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f3693

References

- 1.Lipsitch M, Hayden FG, Cowling BJ, Leung GM. How to maintain surveillance for novel influenza A H1N1 when there are too many cases to count. Lancet 2009;374:1209-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrat F, Vergu E, Ferguson NM, Lemaitre M, Cauchemez S, Leach S, et al. Time lines of infection and disease in human influenza: a review of volunteer challenge studies. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:775-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JT, Ho A, Ma ES, Lee CK, Chu DK, Ho PL, et al. Estimating infection attack rates and severity in real time during an influenza pandemic: analysis of serial cross-sectional serologic surveillance data. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuen KY, Chan PK, Peiris M, Tsang DN, Que TL, Shortridge KF, et al. Clinical features and rapid viral diagnosis of human disease associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. Lancet 1998;351:467-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koopmans M, Wilbrink B, Conyn M, Natrop G, van der Nat H, Vennema H, et al. Transmission of H7N7 avian influenza A virus to human beings during a large outbreak in commercial poultry farms in the Netherlands. Lancet 2004;363:587-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijer A, Bosman A, van de Kamp EE, Wilbrink B, Du Ry van Beest Holle M, Koopmans M. Measurement of antibodies to avian influenza virus A(H7N7) in humans by hemagglutination inhibition test. J Virol Methods 2006;132:113-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Liang W, Yang S, Wu N, Gao H, Sheng J, et al. Human infections with the emerging avian influenza A H7N9 virus from wet market poultry: clinical analysis and characterisation of viral genome. Lancet 2013;381:1916-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, Feng Z, Wang D, Hu W, et al. Human Infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1888-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q, Zhou L, Zhou M, Chen Z, Li F, Wu H, et al. Preliminary report: epidemiology of the avian influenza A (H7N9) outbreak in China. N Engl J Med 2013, 10.1056/NEJMoa1304617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan Y, Farooqui A, Zhu H, Dong W, Wang J, Kelvin DJ. H7N9 incident, immune status, the elderly and a warning of an influenza pandemic. J Infect Dev Ctries 2013;7:302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han J, Jin M, Zhang P, Liu J, Wang L, Wen D, et al. Epidemiological link between exposure to poultry and all influenza A(H7N9) confirmed cases in Huzhou city, China, March to May 2013. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. China-WHO joint mission on human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus (18-24 April 2013): mission report. 2013. www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/influenza_h7n9/ChinaH7N9JointMissionReport2013.pdf.

- 13.Cowling BJ, Freeman G, Wong JY, Wu P, Liao Q, Lau E, et al. Preliminary inferences on the age-specific seriousness of human disease caused by avian influenza A(H7N9) infections in China. Euro Surveill 2013;18:20475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu C, Havers F, Wang L, Chen T, Shi J, Wang D, et al. Monitoring avian influenza A(H7N9) virus through national influenza-like illness surveillance, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2013, 10.3201/eid1908.130662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shu YL, Fang LQ, de Vlas SJ, Gao Y, Richardus JH, Cao WC. Dual seasonal patterns for influenza, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16:725-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu S, Zheng Y, Li T, Hu Y, Liu X, Xi S, et al. Clinical findings for early human cases of influenza A(H7N9) virus infection, Shanghai, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2013, 10.3201/eid1907.130612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Wang L, Hu W, Ding F, Sun H, Li S, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of cases for influenza A(H7N9) virus infections in China. Clin Infect Dis 2013, 10.1093/cid/cit277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]