Abstract

Bacterial vaginosis (BV), a common condition seen in premenopausal women, is associated with preterm labor, pelvic inflammatory disease, and delivery of low birth weight infants. Gardnerella vaginalis is the predominant bacterial species associated with BV, although its exact role in the pathology of BV is unknown. Using immunofluorescence, confocal and transmission electron microscopy, we found that VK2 vaginal epithelial cells take up G. vaginalis after exposure to the bacteria. Confocal microscopy also indicated the presence of internalized G. vaginalis within vaginal epithelial cells obtained from a subject with BV. Using VK2 cells and 35S labeled bacteria in an invasion assay, we found that a 1 h uptake of G. vaginalis was 21.8-fold higher than heat-killed G. vaginalis, 84-fold compared to Lactobacillus acidophilus and 6.6-fold compared to Lactobacillus crispatus. Internalization was inhibited by pre-exposure of cells to cytochalasin-D. In addition, the cytoskeletal protein vimentin was upregulated in VK2 cells exposed to G. vaginalis, but there was no change in actin cytoskeletal polymerization/rearrangements or vimentin subcellular relocalization post exposure. Cytoskeletal protein modifications could represent a potential mechanism for G. vaginalis mediated internalization by vaginal epithelial cells. Finally, understanding vaginal bacteria/host interactions will allow us to better understand the underlying mechanisms of BV pathogenesis.

Keywords: Bacterial vaginosis, Gardnerella vaginalis, Internalization, Cytochalasin-D

1. Introduction

In women of child bearing age, bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common cause of vaginitis and has been associated with fetal loss, chorioamnionitis, cervicitis, endometritis, urinary tract infections, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, pelvic inflammatory disease, preterm labor and delivery of low birth weight infants, as well as an increased risk for HIV-1 infection [1–9]. BV is characterized by the loss of vaginal lactobacilli usually found in healthy women and an overgrowth of anaerobes, including Gardnerella vaginalis and Mycoplasma hominis, as well as Mobiluncus, Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Peptostreptococcus species [10–14]. These events are triggered by mechanisms that are not well understood. Analysis of vaginal biopsies revealed that BV is characterized by a dense biofilm dominated by G. vaginalis and other fastidious anaerobes on the vaginal epithelium [10,15,16]. G. vaginalis alone is insufficient to cause BV in most cases, however this bacterial species is believed to be required for the occurrence of BV and is recovered from virtually all women with BV [17,18]. Recent studies suggest that G. vaginalis is the predominant anaerobe found in BV and is more virulent than other BV associated anaerobes [19]. In an analysis of vaginal adherence, the ability to form biofilms and cytotoxicity, G. vaginalis was shown to have a greater potential for virulence than other BV associated anaerobes [19]. It was suggested that other BV associated bacteria represent avirulent opportunists that colonize the vagina after an initial infection by G. vaginalis. BV is also associated with a high rate of recurrence after standard metranidizole therapy and can be difficult to clinically manage [20]. Recurrent BV has been linked with persistence of G. vaginalis [21]. We therefore surmised that the uptake/internalization of G. vaginalis by vaginal epithelial cells may contribute to the high recurrence rate of BV.

We have taken a molecular approach in an attempt to understand how the physical association between G. vaginalis and the vaginal mucosa could contribute to its persistence on the vaginal epithelium and the pathogenesis of BV. We show in vitro and in vivo data that support uptake of G. vaginalis when exposed to vaginal epithelial cells (VEC), whether they are immortalized VK2 cells or cells obtained from human vaginal lavage samples. Moreover, using a 35S labeling invasion assay, we found evidence of internalization of G. vaginalis and upregulation of the cytoskeletal protein vimentin. This is the first report showing uptake and internalization of G. vaginalis by vaginal epithelial cells. Thus, the results may offer new insights into the overall pathogenesis of BV.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cervicovaginal lavages

Cervicovaginal lavages and subsequent cell samples (CVL) were collected from OB-GYN patients attending clinics at Metro General Hospital in Nashville, TN. CVL specimens were procured using sterile saline following a Meharry Medical College IRB-approved protocol. Samples were designated as BV− or BV+according to Amsel criteria and gram stain results, using a nugent score of ≥7 [14,22]. Specimens were transported to the laboratory on ice for processing. CVL-VEC were examined by wet mount and stained with crystal violet for the presence of clue cells and then gram stained for confirmation of the diagnosis of BV. Smears of CVL-VECs from BV+ and BV− patients were prepared for immunofluorescence (IFA) staining and confocal microscopy.

2.2. Cultivation of the VK2 vaginal epithelial cells

Human immortalized VK2 cells (ATCC 2616), obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, were selected for use because these cells represent squamous vaginal epithelial cells that are sloughed off and contained in vaginal discharges used to clinically identify BV [23]. They represent cells lining the vaginal wall that are in direct contact with the vaginal microflora.VK2 cells were either maintained in keratinocyte serum-free complete media (KSFM) or calcium-free KSFM complete media prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). Cells were passaged by trypsinization and fresh medium was added every three days during cultivations.

2.3. Laboratory cultivation of G. vaginalis, inoculum preparation, and antibody identification

G. vaginalis bacteria ATCC (14018) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cultivation of G. vaginalis was performed using ATCC medium 1685 (NYC III medium). Broth cultures were inoculated with 250 μl of frozen stock bacterial cultures in 1.37% proteose peptone and 6.7% glycerol (stored at −80 °C). Broth cultures were cultivated at 37 °C in an anaerobic chamber using a GasPak system. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in supplemented KSFM complete media. Resuspended cells were quantitated by optical density at OD600 nm. Bacterial suspensions were used to inoculate VK2 cells at 0.34 OD600/ml, which is equivalent to a multiplicity of infection between 10 and 50. G. vaginalis was heat-killed at 80 °C for 20 min in a waterbath.

A specific monoclonal antibody from AbD Serotec (Kidlington, UK) that recognizes a 62 KDa surface protein was used to detect G. vaginalis in VK2 cells and smears from BV+ CVLs by IFA. This antibody was also used to detect G. vaginalis in VK2 cells exposed to bacteria that were also dual labeled for estrogen receptor beta.

2.4. Immunofluorescence

Chamber slides containing monolayers of VK2 cells at a density of 2.5 × 10 5 cells/well were exposed to G. vaginalis for 24 h along with control cultures without bacteria. Cells were washed twice with phosphate buffer saline pH 7.4 (PBS), air dried, and fixed in absolute methanol at −20 °C for 10 min. Cells were then air dried for 15 min, hydrated in Tris saline (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl) pH 7.4 for 5 min and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with a mixture of a rabbit polyclonal antibody to estrogen receptor beta at 1:100 dilution (Millipore Billerica, MA) and a monoclonal antibody to a surface protein (described above) used to identify G. vaginalis at 1:50 dilution. Cells were then washed 3 times with Tris saline and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with a mixture of secondary donkey anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to rhodamine, and donkey anti-mouse antibodies conjugated to FITC (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), both at a 1:100 dilution in PBS (pH 7.4). The cells were then washed in Tris saline and mounted with Vectashield mounting media containing 1.5 μg/ml of DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescent images were observed and photographed with a Nikon TE2000S fluorescent microscope mounted with a CCD camera.

2.5. Confocal and electron microscopy

For confocal microscopy, dual labeled cells stained by immunofluorescence were examined with a Nikon TE2000-U C1 laser scanning confocal microscope with EZC1 2.30 software. Serial Z-sections of 0.05 μm intervals were examined for evidence of bacterial internalization at an excitation of 488 nm. For electron microscopy, VECs exposed to G. vaginalis for 1 h were washed twice in sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 h and held at 4 °C for an additional 24 h. Vaginal epithelial cell monolayers were then rinsed twice with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h, washed twice for 5 min in cacodylate buffer and dehydrated in graded ethanol. Samples were embedded in spur resin, sectioned for standard EM analysis and visualized on a Phillips CM12 electron microscope.

2.6. Radiolabeling of G. vaginalis, Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus crispatus

VK2 cells were cultured in 12-well dishes in complete KSFM media. G. vaginalis was cultivated in NYC III media at 37 °C for 48 h under anaerobic conditions. L. acidophilus and L. crispatus, used as a controls, were grown under aerobic conditions in deMan, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) media (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) at 37 °C for 24 h because G. vaginalis grew slower in our hands than the lactobacillus species. G. vaginalis, L. acidophilus and L. crispatus were pelleted for 10 min at 2500 rpm in a Thermo Sorvall Kegen RT centrifuge and washed with PBS at 37 °C. Pellets were resuspended in methionine-free RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 0.2% glucose. 35S methionine (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) at a concentration of 50 μCi/mL was added to the bacterial cultures which were then incubated anaerobically (G. vaginalis) or aerobically (L. acidophilus and L. crispatus) at 37 °C for 3 h. Mock control bacteria without 35S methionine were also included. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in pre-warmed PBS and washed 3 times and resuspended in KSFM media to an OD600 of 0.38.

2.7. Cytochalasin-D treatment of VEC cells

Cytochalasin-D (Enzo Life Sciences, Plymouth Meeting, PA) was resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 and 5 μg/ml in KSFM media and added to VK2 cells 1 h before adding 35S labeled bacteria at 0.38 OD600. Control wells contained radiolabeled bacteria without cytochalasin-D. Monolayers were then incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2, washed 6 times with PBS at 37 °C and trypsinized for 20 min with 200 μl of 0.08% trypsin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to remove extracellular bacteria. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min at 10,000 rpm, washed 3 times in PBS and lysed with 200 μl of 1% Triton X-100. Cell lysates (200 μl) were read on a Packard Tri-Car 2300 TR Liquid Scintillation Counter percent cpms recovered were calculated using the equation (recovered cpm/added cpm) × 100.

2.8. Western blots

Extracts from VK2 exposed to G. vaginalis, heat-killed G. vaginalis, L. acidophilus and L. crispatus for 24 h as well as extracts from mock infected cells were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1% NP40, 0.5% deoxycholate sodium, 0.1% SDS and proteinase inhibitor). Lysates were placed on ice for 30 min, clarified by centrifugation and total protein measured by the BCA assay (Pierce Biotechnology; Rockford, IL). Fifteen μg of protein lysates from mock and G. vaginalis exposed cells were fractionated in 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked with 5% milk, 0.1% TBST (0.1% Tween 20, 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl) and incubated at 4 °C overnight with either primary monoclonal antibodies to vimentin or actin (BD Laboratories, San Diego, CA). Both antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:2000. Membranes were washed 5 times in washing buffer (0.1% TBST) and incubated for 1 h followed by incubation with a donkey anti-mouse peroxidase conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at a dilution of 1:10,000. Immunoreactive bands were detected with SuperSignal West-Dura extended substrate (Pierce) following exposure on X-ray film.

2.9. Densitometry

Densitometry analysis was performed on immunoblots from mock and G. vaginalis exposed VK2 cells using a BIO RAD Chemi-Doc XRS gel docking system and Quantity One 4.6.2 software.

2.10. RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from G. vaginalis exposed VK2 cells and mock infected cells using a Qiagen mini RNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The RNA was DNAase treated prior to elution on the column according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Messenger RNA in 0.5 μg of each sample was primed using oligo-dT and reverse transcribed with a High Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA.). Gene specific vimentin primer pairs, forward 5′-CCCTCACCTGTGAAGTGGAT-3′ and reverse 5′-TCCAGCAGCTTCCTGTAGGT-3′, were used; 10 ng of cDNA was used for RT-PCR amplification. PCR was performed using PuReTaq Ready–To-Go PCR beads (GE Health Care, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. PCR was carried out in a MJ Mini thermocycler in a final volume of 25 μl. The following cycling protocol was used: 95 °C for 5 min, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min (for 36 cycles), with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose and DNA bands were visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. Vimentin specific bands are shown as a 249 bp fragment. GAPDH was amplified in mock and exposed VK2 cells as a loading and quality control and is represented by a 240 bp fragment.

2.11. Statistical analysis

The data presented represents independent experiments and are presented as mean ± SD and were analyzed using Student‘s t test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic characterization of VK2 cells

VK2 cell monolayers were stained by immunofluorescence in order to detect cytoskeletal, cell adhesion, proliferation and functional biomarkers. Cells were noted positive if fluorescence intensity was above background levels and by examining the same microscopic field in the rhodamine channel of the microscope for comparison. Commercial sources of all antibodies tested are listed in Table 1. The VK2 cell line used in this study was examined by immunofluorescence staining to determine its antigen expression profile. We observed that normal VK2 cells expressed cytoskeletal proteins fibronectin, vimentin and beta catenin but not alpha actin or any of the cell adhesion markers examined in this analysis (Table 1). VK2 cells also expressed the nuclear proliferation antigen Ki67, which was expected because of their transformed state, as well as their epithelial specific antigen and estrogen receptor beta.

Table 1.

Potential VK2 Cell biomarkers.

| Antigen classification | Cellular antigens examined | VK2 reactivity | Source of antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoskeletal | Fibronectin | + | R&D Systems |

| Alpha actin smooth muscle | − | Abcam | |

| Vimentin | + | BD Bioscience | |

| Beta Catenin | + | Millipore | |

| Cellular adhesion | PECAM-1/CD31 | − | Millipore |

| VCAM-1/CD106 | − | R&D Systems | |

| ICAM-1/CD54 | − | Santa Cruz | |

| MelCAM/CD146 | − | Santa Cruz | |

| E selectin | − | R&D Systems | |

| VE Cadherin | − | BD Bioscience | |

| VWF | − | Millipore | |

| Alpha 4 Integrin | − | R&D Systems | |

| Functional Proliferation | Ki67 | + | BD Bioscience |

| Epithelial specific-Ag | + | Millipore | |

| Estrogen receptor-B | + | Millipore |

4. G. vaginalis internalization by VK2 cells and isolated CVL cells from a BV+ subject

We exposed VK2 cells to G. vaginalis resuspended in complete VK2 growth media for 24 h. When we dual stained bacteria-exposed monolayers with antibodies specific for estrogen receptor beta and a surface protein of G. vaginalis, we obtained visual evidence suggesting uptake/internalization of G. vaginalis by VK2 cells (Fig. 1A). FITC labeled G. vaginalis can be seen in the cytoplasm, including the perinuclear regions of these cells (Fig. 1B). Fig. 1A and B are representative of the cytoplasmic association and cytoplasmic internalization processes, respectively, that were observed among the different cells in culture, some of which took up G. vaginalis and some of which did not. This heterogeneity of uptake was a common feature throughout multiple cultures of VK-2 cells exposed to G. vaginalis.

Fig. 1.

Internalization of VEC cells by G. vaginalis. VK2 vaginal epithelial cells were exposed to G. vaginalis for 24 h. Cells were then fixed and dual stained for estrogen receptor beta (rhodamine) and G. vaginalis (FITC). DAPI was used to stain nuclei blue. Total magnification was 600×. (A). Cytoplasmic association of G. vaginalis with VK2 cells.(B). Cytoplasmic internalization of G. vaginalis by VK2 cells.(C). Confocal image of vaginal epithelial cells from a BV+ patient dual stained for estrogen receptor beta (rhodamine) and G. vaginalis (FITC). Shows top view of 3 vaginal epithelial cells from a BV+ patient. Cell #2 is a clue cell stained positive for G. vaginalis. (D). A confocal microscopy image of the same VEC cells from the BV+ patient shown in (C) but indicating G. vaginalis presence within isolated VEC cells using serial Z-sectioning at 0.50 μm intervals.

In addition, we obtained vaginal CVL cells from 4 BV+ and 4 BV− patients (CVL-1-8) for two purposes: first to determine our ability to successfully isolate and cultivate these VEC under minimally invasive conditions and second, to help validate our VK2 results. For the latter, we dual stained CVL specimens from BV+ subjects [14,22]. To determine the localization of the bacteria in reference to the cell surface and intracellular space, we performed confocal microscopy. In these experiments, we focused on 3 cells, 2 of which were clue cells stained positive for G. vaginalis, as can be seen in Fig. 1C. After analysis of surface contact points of the bacteria on VEC by top views and Z-sectioning analysis, the data were consistent with our previous observations that bacteria lie within a plane that is internal to the cell rather than on the surface of the cell (Fig. 1D). This finding was consistent with findings obtained with CVL specimens from the other BV+ subjects and is typical of the data obtained in these experiments. Marginal staining of G. vaginalis was observed with CVL cells from BV− patients.

4.1. Internalization of G. vaginalis by TEM

Next, we performed ultrastructural analysis of VK2 cells after exposure to G. vaginalis to confirm the bacterial uptake and internalization observed by immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy. VK2 cell monolayers were exposed to G. vaginalis for 1 h at a MOI of 10–50 under previously described conditions. Bacteria-exposed cells were then examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We observed bacteria in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A) with the morphology and dimensions of G. vaginalis (Fig. 2B). Bacteria were observed in both cytoplasmic (Fig. 2C) and perinuclear regions (Fig. 2D) of VK2 cells. The size and morphology of the bacteria were consistent with TEM analyses of bacteria in cell pellets from pure cultures of G. vaginalis (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of VK2 cells exposed to G. vaginalis for 1 h. Bacterial cell dimensions are given in nanometers (arrows and white text). The bars at the bottom of B–D represent length in nanometers.(A). G. vaginalis bacteria in the cytoplasm of VK2 cells. (B). The same cytoplasmic bacteria in (A) with dimensions shown in nm consistent with that of G. vaginalis. (C). G. vaginalis is shown intracellularly, but located near the cell surface and throughout the cytoplasm of VK2 cells. (D). This view shows a perinuclear presence of G. vaginalis in VK2 cells.

4.2. G. vaginalis uptake by VK2 cells in an invasion assay

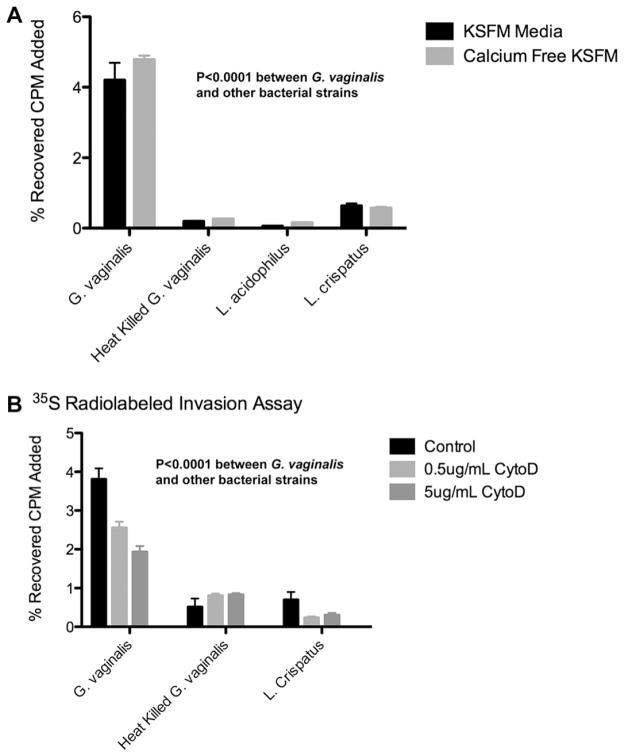

We performed a 1 h invasion assay comparing the relative VK2 cell uptake of 35S methionine-labeled G. vaginalis, heat-killed G. vaginalis, L. acidophilus and L. crispatus. To determine if calcium flux activation of RhoGTPase was associated with cytoskeletal changes that contributed to uptake of G. vaginalis [32,33], we first performed the assay in both KSFM and calcium-free KSFM media (Fig. 3A). After extensive washing and cell lysis we showed that the % recovery of radioactivity in lysates obtained from incubations in KSFM media was 4.0% for G. vaginalis compared to 0.19% for heat-killed G. vaginalis, 0.05% for L. acidophilus and 0.63% for L. crispatus. Similar results were obtained when cells were incubated in calcium-free KSFM, indicating that RhoATPase was not involved in the uptake seen in incubations with G. vaginalis. The data also show that G. vaginalis was clearly more invasive over this time period than heat-killed G. vaginalis, L. acidophilus and L. crispatus. However, L. crispatus did have a small, but statistically significant uptake compared to L. acidophilis and heat-killed G. vaginalis.

Fig. 3.

Invasion assays using 35S labeled bacteria and VK2 cells ± cytochalasin-D. (A). VK2 cells exposed separately to 35S labeled G. vaginalis, heat-killed G. vaginalis, L. acidophilus and L. crispatus for 1 h, using either KSFM or calcium-free KSFM media. Results indicate the % recovery of labeled bacteria in lysates after a washing procedure. (B). Cytochalasin-D treatment of VK2 cells inhibited uptake of G. vaginalis by VK2 cells in a dose-dependent manner.VK2 cells were pretreated for 1 h with, or without (controls) 0.5 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml of cytochalasin-D in KSFM media. Radioactive 35S labeled G. vaginalis, heat-killed G. vaginalis, L. acidphilus or L. crispatus was added at an OD600 of 0.38. Shown are values ± SD.

4.3. Inhibition of G. vaginalis uptake by cytochalasin-D

Cytochalasin-D is a potent inhibitor of actin polymerization. Fig. 3B shows that the addition of cytochalasin-D greatly reduced G. vaginalis and L. crispatus uptake/internalization in VK2 cells in a concentration dependent manner. This suggests that a functional VK2 cell cytoskeleton and active cell metabolism are required for efficient G. vaginalis and L. crispatus uptake. While the uptake of 35S radiolabeled G. vaginalis was higher than that seen with 35S labeled L. crispatus, there was no significant difference in the uptake of 35S labeled heat-killed G. vaginalis before and after treatment with cytochalasin-D.

4.4. Vimentin upregulation in VEC cells after exposure to G. vaginalis

To determine a potential mechanism involved in uptake and internalization of G. vaginalis by VK2 cells, we examined the expression of cytoskeletal proteins that have been shown to be associated with adherence and invasion of eukaryotic cells by bacteria. We found upregulation of vimentin (protein and mRNA) in VK2 cells exposed to G. vaginalis compared to mock treated control cells (Fig. 4). Vimentin (Fig. 4A) was the only cytoskeletal protein examined in this study that showed a differential expression after exposure to G. vaginalis (data not shown for other cytoskeletal proteins listed in Table 1). Vimentin was upregulated 2.1-fold in VK2 cells exposed to G. vaginalis when compared to mock control VK2 cells (Fig. 4B). We then compared vimentin transcriptional expression levels in VK2 cells exposed to L. acidophilus and L. crispatus. G. vaginalis exposed cells revealed a slight but noticeable increase in vimentin protein expression when compared to L. acidophilus and L. crispatus (4C).

Fig. 4.

Vimentin upregulation in VK-2 exposed to G. vaginalis. (A). VK-2 cells were exposed to G. vaginalis for 24 h, then screened by Western blot for vimentin expression. Differential expression of vimentin is seen in comparison to mock treated controls. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (B). Densitometry analysis revealed a 2.1-fold increase in the amount of vimentin in lysates from G. vaginalis exposed VK2 cells, compared to mock infected controls. (C). Untreated VK-2 cells (controls) to VK-2 cells exposed for 24 h to G. vaginalis, L. acidophilus, orL. crispatus were evaluated for vimentin expression by Western blot analysis. Differential expression of vimentin was seen in comparison to mock treated controls. (D). Expression of vimentin by qRT-PCR in VK-2 cells 24 h after exposure to L. acidophilus, L. crispatus, or G. vaginalis. Differential expression of vimentin was seen in comparison to L. acidophilus and L. crispatus or controls. Fold difference in transcriptional expression was normalized to GAPDH. (E). qRT-PCR analysis of vimentin mRNA expression in VK-2 cells at 1, 18, and 24 h with and without exposure to G. vaginalis. The expected fragment size for vimentin is 249 bp. GAPDH was amplified as a loading control with a fragment size of 240 bp.

We then examined vimentin mRNA expression by qRT-PCR in VK2 cells after 24 h exposure to L. acidophilus and L. crispatus and G. vaginalis. We observed a significant increase in vimentin transcriptional expression in G. vaginalis exposed cells when compared to L. acidophilus (p = 0.0052) and L. crispatus (p = 0.00056) exposed VK2 cells. We also observed a time-dependent upregulation in vimentin transcription in VK2 cells after 1, 18, and 24 h post exposure to G. vaginalis by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 4E).

To determine if actin cytoskeletal rearrangements occurred after exposure of VK2 cells to G. vaginalis, we performed dual labeled immunofluorescent staining of cells exposed to bacteria for 1 h. Exposed cells were fixed and stained with antibodies to estrogen receptor-β and β-actin. We observed no change in actin polymerization or rearrangement (data not shown). VK2 cells actin was found to be poorly stained with rhodamine–phalloidin in our hands (data not shown). When we used another actin antibody from a different commercial source (ABCAM, Cambridge, MA), we again saw no changes. We also examined these same VK2 cells for alteration in vimentin subcellular localization and found no difference in subcellular localization of vimentin in G. vaginalis exposed and unexposed cells (data not shown).

5. Discussion

Using VK2 cells, we observed that the uptake of G. vaginalis, the predominant species of abnormal vaginal bacteria associated with BV, was suppressed by exposure of the cells to cytochalasin-D. This observation may provide important clues to long standing questions with regard to G. vaginalis and its contribution to BV pathogenesis. We showed evidence for uptake/internalization of G. vaginalis by VK2 cells as well. We realize that the VK2 cells used in these in vitro studies are not polarized and may be quite different from resident epithelial cells encountered in vivo. However we were also able to show evidence that G. vaginalis was internalized within CVL cells obtained from BV+ subjects. This intra-cellular localization could allow G. vaginalis to escape immune surveillance and the effects of therapy with metronidazole and clindamycin [24,25], which represent the standard of care for treating BV. Thus, this internalization process could contribute to the high rate of recurrence of BV in some women [20,21]. Moreover, the intracellular presence of G. vaginalis in the genital tract could allow the organism to evade an immune response. A persistent intracellular presence of G. vaginalis would stimulate cytokine cascades that might heighten the inflammatory state of the vaginal epithelium making it more susceptible to infections. Therefore this study may offer insights into the high recurrence rate of BV, which remains a problem.

We observed dysregulation of the the cytosketal protein vimentin after exposure of VK2 cells to G. vaginalis. Vimentin has been shown to contribute to adhesion, invasion and intracellular infection of endothelial cells [26] and epithelial cells [27]. Vimentin also has been shown to play a role in bacterial pathogenesis. Group A streptococci, for instance, have been found to bind to vimentin on the surface of skeletal muscle cells during myonecrosis [28]. The Salmonella virulence protein SptP can interact with vimentin, resulting in vimentin recruitment to membrane ruffles [29]. Furthermore, a protein toxin from Pasteurella multocida has been reported to bind vimentin head domains [30]. Previous reports by Zou et al., 2006 [26], identified vimentin as the host factor that interacts with an invasion protein encoded by the IbeA gene of Escherichia coli K1 strain RS218. This interaction facilitates binding to, and invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells by E. coli K1 RS218 in the condition of neonatal meningitis. The 50 KDa IbeA gene product has been identified as a virulence factor for E. coli K1 RS218. No homologs of the IbeA gene have been identified in any other bacterial species; recently however, genomic sequencing of clinically relevant strains of G. vaginalis have been completed that will allow the identification of related virulence factors or IbeA homologs [31]. Fine mapping of the interactions between residues on the IbeA protein and the head domain of vimentin have been determined, as well as the regulatory Xa protease that was found to disrupt this interaction [26]. We have ongoing studies to identify IbeA homologs in G. vaginalis. If identified, we will clone and characterize such homologs to determine their potential role in the uptake and internalization of G. vaginalis by squamous vaginal epithelial cells.

This study may serve as a means to help identify cellular targets that could lead to novel and more effective therapies for BV, thereby reducing the impact of BV associated co-morbidities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Diana Marver and Jared Elzey for reviewing this manuscript. This work is supported by the Meharry-Vanderbilt Center for AIDS Research, (NIH P30 AI054999); the Meharry Center for AIDS Health Disparities Research (NIH 5U54 RR019192); the Meharry Translational Research Center (NIH P20RR011792); the Research Centers in Minority Institutes program (NIH G12RR003032); and the Vanderbilt CTSA (1UL1 RR024975) from NCRR/NIH (D.J.A.); and C.N.M was supported by the Research Initiative for Scientific Enhancement (NIH 5 R25 GM059994) from NIGMS and Training grant NIH 5 T32 HL007737 (T32) NHLBI.

References

- 1.Holst E, Goffeng AR, Andersch B. Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal microorganisms in idiopathic premature labor and association with pregnancy outcome. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;1:176–186. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.176-186.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meis PJ, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, et al. The preterm prediction study: significance of vaginal infections. National institute of child health and human development maternal-fetal medicine units network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;4:1231–1235. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for postcesarean endometritis. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larson PG, Platz-Christensen JJ, Thejis H, Forsum U, Pahlson C. Incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease after first trimester legal abortion in women with bacterial vaginosis after treatment with metronidazole: a double blind, randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:100–103. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romero R, Gonzalez R, Sepulveda W, et al. Infection and labor. VIII. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in patients with suspected cervical incompetence: prevalence and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;4:1086–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)80043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gravett MG, Hummel D, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Preterm labor associated with subclinical amniotic fluid infection and with bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:229–237. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198602000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibbs RS, Weiner MH, Walmer K, St Clair PJ. Microbiologic and serologic studies of Gardnerella vaginalis in intra-amniotic infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;2:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant, the vaginal infections and prematurity study group. N Engl J Med. 1995;26:1737–1742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taha TE, Hoover DR, Dallabetta GA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and disturbances of vaginal flora: association with increased acquisition of HIV. Aids. 1998;13:1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fredericks DN, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM. Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1899–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis: resistance, recurrence, and/or reinfection? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:213–219. doi: 10.1086/509584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillier SL. Diagnostic microbiology of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:455–459. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90340-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spiegel CA. Bacterial vaginosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:485–502. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KCS, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner HL, Dukes CD. Haemophilus vaginalis vaginitis: a newly defined specific infection previously classified non-specific vaginitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1955;69:962–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swidsinski A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, Ladhoff A, Swidsinski S, Hale LP, Loch H. Adherent biofilms in bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1013–1023. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183594.45524.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catlin BW. Gardnerella vaginalis: characteristics, clinical considerations, and controversies. Clin Microbiol. 1992;5:213–237. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marrazzo JM, Thomas KK, Fiedler TL, Ringwood K, Fredricks DN. Relationship of specific vaginal bacteria and bacterial vaginosis treatment failure in women who have sex with women. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:20–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-1-200807010-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson JL, Stull-Lane A, Girerd PH, Jefferson KK. Analysis of adherence, biofilm formation and cytotoxicity suggests a greater virulence potential of Gardnerella vaginalis relative to other bacterial vaginosis-associated anaerobes. Microbiology. 2010;156:392–399. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034280-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Curr Infect Dis. 2002;2:506–512. doi: 10.1007/s11908-000-0053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bannnatyne RM, Smith AM. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis and metranidazole resistance in Gardnerella vaginalis. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74:455–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fichorova RN, Rheinwald JG, Anderson DJ. Generation of papillomavirus-immortalized cell lines from normal human ectocervical, endocervical, and vaginal epithelium that maintain expression of tissue-specific differentiation proteins. Biol Reprod. 1997;4:847–855. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.4.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boris J, Pahlson C, Larson PG. Six years of observation after successful treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1997;5:297–302. doi: 10.1155/S1064744997000513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou Y, He L, Huang SH. Identification of a surface protein on human brain microvascular endothelial cells as vimentin interacting with Escherichia coli invasion protein IbeA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;3:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, Yan Q, Long X, Chen X, Wang Y. Vimentin affects the mobility and invasiveness of prostate cancer cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2008;5:571–577. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryant AE, Bayer CR, Huntington JD, Stevens DL. Group A Streptococcal myonecrosis: increased vimentin expression after skeletal-muscle injury mediates the binding of Streptococcus pyogenes. J Infect Dis. 2006;12:1685–1692. doi: 10.1086/504261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murli S, Watson RO, Galan JE. Role of tyrosine kinases and the tyrosine phosphatase SptP in the interaction of Salmonella with host cells. Cell Microbiol. 2001;12:795–810. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shime H, Ohnishi T, Nagao K, Oka K, Takao T, Horiguchi Y. Association of Pasteurella multocida toxin with vimentin. Infect Immun. 2002;11:6460–6463. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6460-6463.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeoman CJ, Yildirim S, Thomas SM, Durkin AS, Torralba M, Sutton G, Buhay CJ, Ding Y, Dugan-Rocha SP, Muzny DM, Qin X, Gibbs RA, Leigh SR, Stumpf R, White BA, Highlander SK, Nelson KE, Wilson BA. Comparative genomics of Gardnerella vaginalis strains reveals substantial differences in metabolic and virulence potential. PLos One. 2010;8:e12411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iliev AI, Djannatian JR, Nau R, Mitchell TJ, Wouters FS. Cholesterol-dependent actin remodeling via RhoA and Rac1 activation by the Streptococcus pneumoniae toxin pneumolysin. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2007;104:2897–2902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608213104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madden JC, Ruiz N, Caparon M. Cytolysin-mediated translocation (CMT): a functional equivalent of type III secretion in gram-positive bacteria. Cell. 2001;104:143–152. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]