Abstract

Background & Aims

Direct-acting anti-viral agents suppress hepatitis B virus (HBV) load but must be given lifelong. Stimulation of the innate immune system could increase its ability to control the virus and have long lasting effects, after a finite regimen. We investigated the effects of immune activation with GS-9620—a potent and selective orally active small molecule agonist of Toll-Like Receptor (TLR)7—in chimpanzees with chronic HBV infection.

Methods

GS-9620 was administered to chimpanzees every other day (3 times each week) for 4 weeks at 1 mg/kg and, after a 1 week rest, for 4 weeks at 2 mg/kg. We measured viral load in plasma and liver samples, the pharmacokinetics of GS-9620, and the following pharmacodynamics parameters: interferon (IFN)-stimulated gene expression, cytokine and chemokine levels, lymphocyte and natural killer cell activation, and viral antigen expression. Clinical pathology parameters were monitored to determine the safety and tolerability of GS-9620.

Results

Short-term oral administration of GS-9620 provided long-term suppression of serum and liver HBV DNA. The mean maximum reduction of viral DNA was 2.2 logs, which occurred within 1 week of the end of GS-9620 administration; reductions of greater than 1 log persisted for months. Serum levels of HB surface antigen and HB e antigen, and numbers of HBV antigen-positive hepatocytes, were reduced as hepatocyte apoptosis increased. GS-9620 administration induced production of IFN-α and other cytokines and chemokines, and activated ISGs, natural killer cells, and lymphocyte subsets.

Conclusions

The small molecule GS-9620 activates TLR-7 signaling in immune cells of chimpanzees to induce clearance of HBV-infected cells. This reagent might be developed for treatment of patients with chronic HBV infection.

Keywords: innate immunity, interferon-α, antiviral, pathogen recognition

Introduction

Therapeutic treatment of chronic HBV infection is currently limited to nucleos(t)ide analogues and pegylated-interferon-α (peg-IFN-α).1, 2 First line therapy for HBV is limited to the two nucleos(t)ide analogues tenofovir and entecavir which are highly effective at suppressing viral replication and can reduce serum viral load to undetectable levels. However these agents do not lead to viral eradication, thus potentially requiring life-long use and possible emergence of resistance.3 The potential for therapeutic immune modulation to treat HBV chronic infection is illustrated by durable responses, normalization of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and sustained reduction in viremia attained in a small percentage (less than 20%) of patients treated for one year with peg-IFN-α.4–6 A key observation is the apparent cure rate following long-term high-dose IFN-α treatment increases for several years after treatment, based on loss of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and seroconversion for anti-HBsAg antibody. This supports the hypothesis that viral control is due to immune modulation and slow induction of a protective antiviral immune response. The low rate of HBsAg loss and seroconversion with current therapies illustrate the need for new approaches to induce a protective anti-viral immune response and durable cure in patients with chronic HBV.

Toll-like receptor-7 (TLR-7) is a pathogen recognition receptor predominantly expressed in lysosomal/endosomal compartments of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and B lymphocytes that recognizes a pathogen-associated molecular pattern in viral single-stranded RNA.7 Upon stimulation of TLR-7, pDCs produce IFN-α 8, 9 and other cytokines/chemokines and cause activation of NK cells and cross-priming of cytotoxic lymphocytes,10 thereby orchestrating both innate and adaptive immune responses.11 For these reasons, TLR-7 has been pursued as a therapeutic target for cancer, viral infections, and other diseases.12–15 GS-9620 is a potent, orally active TLR-7 agonist with selectivity for induction of IFN-α over pro-inflammatory cytokines. Here, we demonstrate that a TLR-7 agonist provides therapeutic efficacy for treatment of HBV chronic infection in chimpanzees, the only primate model of persistent HBV infection.16, 17 The immune modulation induced by activation of TLR-7 resulted in rapid reduction of viremia, reduction in serum HBsAg and e antigen (HBeAg) levels, and an apparent reduction of the numbers of infected hepatocytes with short-term therapy, and provided prolonged suppression of viremia after termination of therapy.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatment

Chimpanzees were housed at the Southwest National Primate Research Center (SNPRC) at Texas Biomedical Research Institute. The animals were cared for in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Details on animal care and animal histories are provided in Supplementary Materials and Methods. The trial design included 4 weeks of pre-study evaluation (Day -28, -13 and just prior to first dose) and two cycles of oral GS-9620 treatment every other day three times per week for 4 weeks with one cycle at 1 mg/kg, and, after a one week rest, a second cycle at 2 mg/kg. Animals were also intensely monitored for 14 weeks after treatment to assess tolerability and durability of response.

Assays for HBV DNA and Viral Antigens

HBV DNA levels were determined for the serum and liver biopsy samples in multiple assays during the study period. Serum levels were measured by AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HBV Test, v2.0 and by an in-house TaqMan assay,18 see Supplementary Materials for details. Serum levels of HBsAg and HBeAg were determined by ELISA (DiaSorin ELISA kits ETI-MAK-2 PLUS and ETI-EBK PLUS, respectively). Immunohistochemical staining was performed on formalin fixed liver tissue after antigen retrieval as previously described 19 and further described in Supplementary Materials.

Quantitation of ISG Transcript Levels by RT-PCR

The transcript levels for OAS, MX1, ISG15, I-TAC, IP-10, TLR-7 and GAPDH were determined by quantitative TaqMan RT-PCR as previously described.19 Briefly, 200 ng of total cell RNA from liver or PBMC was analyzed by qRT-PCR assay using primers and probe from ABI Assays-on-Demand™ and an ABI 7500 sequence analyzer (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX).

Flow Cytometry

Evaluations of lymphocyte subpopulations were performed using an eleven parameter CyAn ADP Flow Cytometer (Beckman-Coulter Inc, Fullerton, CA). All data were expressed as percentage of lymphocytes that have the specified surface markers. Detailed methods are provided in Supplementary Materials.

Cytokine and Chemokine Analysis

Monitoring of cytokines and chemokines was performed by Luminex 100 with the xMAP (multi-analyte platform) system using a 39-plex human cytokine/chemokine kit (Millipore; Billerica, MA). Dilutions of standards for each cytokine were evaluated in each assay. Cytokines were evaluated in serum samples at 0 and 8 h post-dose.

Results

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of GS-9620 in Uninfected Chimpanzees: Induction of Interferon Response and Cytokines-Chemokines by TLR-7 Agonist GS-9620

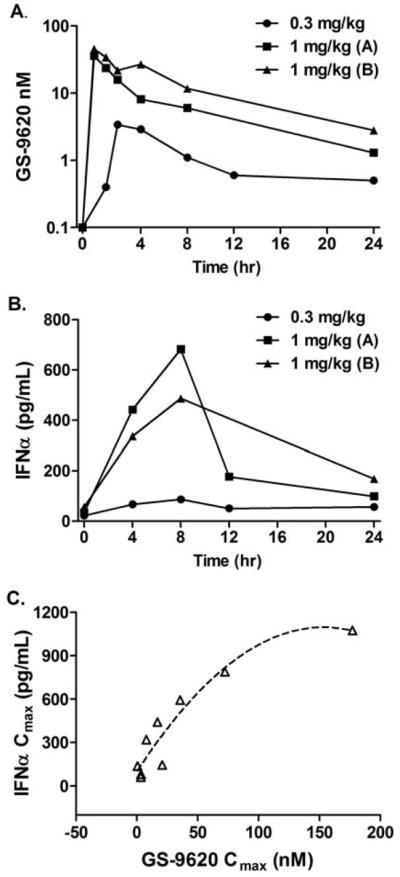

GS-9620, a potent selective TLR7 agonist, was designed to have rapid clearance and low level systemic exposure following oral administration to allow for transient TLR7 stimulation. Consistent with the selectivity of GS-9620 and the biology of TLR7, chimpanzee PBMCs stimulated in vitro with GS-9620 displayed a lower minimum effective concentration for IFN-α, chemokines CXCL10 (IP-10), CCL7 (MCP-3), and CCL4 (MIP-1β), IL-1 Receptor Antagonist (IL-1RA), and IFN-γ in comparison to proinflammatory cytokines (Supplementary Table 1). In vivo, single oral doses of GS-9620 at 0.3 and 1 mg/kg in uninfected chimpanzees demonstrated a dose- and exposure-related induction of serum IFN-α, select cytokines/chemokines, and interferon-stimulated genes (ISG) in the peripheral blood and liver. Following oral administration at 0.3 (n=3), and 1 mg/kg (n=3 and n=4), GS-9620 Cmax was 3.6 ± 3.5, 36.8 ± 34.5, and 55.4 ± 81.0 nM, respectively. Peak serum interferon responses occurred at 8 h post-dose and are shown in Figure 1. The mean peak levels of induced serum IFN-α were 66 and 479 pg/mL at doses of 0.3 and 1 mg/kg, respectively (Figure 1). GS-9620 treatment induced ISG transcripts including ISG15, OAS-1, MX1, IP-10 (CXCL10), and I-TAC (CXCL11) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (Supplementary Table 2) at 0.3 mg/kg and in both PBMC and the liver at 1 mg/kg (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Serum levels of 42 different cytokines were evaluated. The magnitude and breadth of cytokine induction correlated with GS-9620 dose (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3). The 0.3 mg/kg dose induced 3-fold or greater increases in serum IL-7, IL-10, IP-10, fractalkine, IL-1α, IL-1RA, and G-CSF, whereas the 1 mg/kg dose induced 3-fold or greater increases in the same cytokines (except IL-7) and serum IL-12p40, IL-12p70, MCP-1, MCP-3, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-β, and neopterin. GS-9620 was well tolerated in uninfected chimpanzees; the only drug-related changes were transient increases in peripheral blood neutrophils and decreases in lymphocytes, consistent with cell trafficking induced by the above cytokines and chemokines. Based on these data, 1 mg/kg was selected as the starting dose for treatment of HBV infected animals.

Figure 1. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of GS-9620 in uninfected chimpanzees.

Chimpanzees were dosed orally with GS-9620 with 0.3 mg/kg (n=3) or 1.0 mg/kg (group A, n=3; group B, n=4) and blood levels of GS-9620 (A) and IFN-α (B) were determined over 24 h. Maximum concentration (Cmax) was determined for GS-9620 and IFN-α for each animal (C). The same three animals were used in each dose group with a fourth animal added to group B.

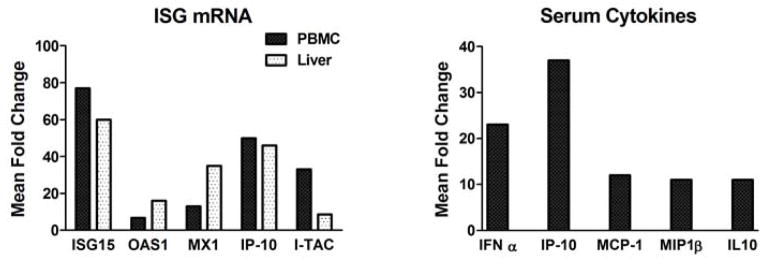

Figure 2. Fold induction of ISG transcripts and serum cytokines/chemokines following a single oral dose of GS-9620 in uninfected chimpanzees.

The increases in ISG transcripts were quantified by TaqMan RT-PCR in PBMC and liver and are expressed as the maximum mean fold increase from the baseline samples following a single dose of 1 mg/kg GS-9620. Increases in serum cytokines and chemokines were quantified in the same animals by Luminex and are expressed as the mean fold increase from samples obtained prior to each dose (0 h) and 8 h post-dose. The mean values are derived from two experiments with n=3 and n=4. The same three animals were used in both studies with one additional animal present in the second study.

Antiviral Efficacy of TLR-7 Agonist GS-9620 in HBV Infected Chimpanzees

Therapeutic evaluation was performed in three chimpanzees that had chronic HBV infections for over 24 years. One chimpanzee (4x0139) had high baseline serum HBV DNA, while the other two chimpanzees (4x0328 and 4x0506) had lower HBV DNA levels at baseline (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 4). Serum levels of HBV DNA declined gradually in all three animals during the first treatment cycle with a 1-log reduction in the high-titer animal (Figure 3A). The second treatment cycle caused a continued but more rapid decline of viral DNA in all three animals (Figure 3A-C) with a maximum viral reduction of 2.8 logs and a mean reduction of 2.2 logs (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 5). Suppression of serum viral DNA levels by more than 1 log persisted for a minimum of 64 days. The viral load in the high-titer animal (animal 4x0139) was 1.8 logs below baseline at the end of the study, day 121, and remained more than 1 log below baseline for 280 days after initiation of dosing. The two low viral load animals returned to within 1 log of baseline within 100 and 71 days of the initiation of dosing, but continued to be suppressed by approximately 1 log for 1 to 2 years after this study.

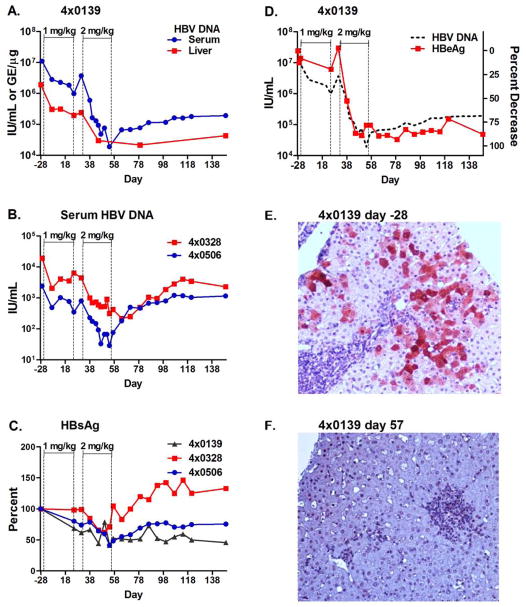

Figure 3. Decline in HBV during GS-9620 therapy in HBV infected chimpanzees.

Three chimpanzees chronically infected with HBV were dosed orally three times per week for 4 weeks with 1 mg/kg (day 1–25) and then for 4 weeks at 2 mg/kg, (day 31–57) with a 1 week rest between dosing cycles. HBV DNA in serum (IU/mL) and liver (genome equivalents per μg of liver DNA; GE/μg) were determined by qPCR for animal 4x0139 (A) and in serum for animals 4x0328 and 4x0506 (B). HBsAg was determined by ELISA in the serum of all three animals (C) and HBeAg levels were determined by ELISA in the serum of animal 4x0139 (D). The level of serum HBV DNA from panel A is shown as a dashed line in panel D for reference. Immunohistochemical staining of HBV core antigen was performed on formalin-fixed sections of liver from 4x0139 prior to dosing on Day -28 (E) and on Day 57 (F), the last day of dosing at 2 mg/kg.

Treatment also caused a decline in HBV viral DNA in the liver of the high-titer animal (animal 4x0139). The decline in liver HBV DNA paralleled the decline in serum DNA, 1.0 and 2.1 logs at the end of the first and second treatment cycles, respectively. The two low HBV DNA titer animals (animals 4x0328 and 4x0506) had very low levels of hepatic HBV DNA at baseline and did not exhibit a significant decline in viral DNA in the liver during therapy (data not shown). The apparent lack of decline in hepatic viral DNA may have been due to limitations in the assay and background in the assay imposed by the presence of integrated viral DNA.

HBsAg and HBeAg are secreted from HBV infected hepatocytes independent of viral particles and are important clinical markers of infection independent of viral DNA levels. In the high-titer animal (4x0139), GS-9620 treatment reduced HBsAg and HBeAg serum levels by 61% and 93% from baseline, respectively (Figure 3 C and D), and levels remained suppressed through post-treatment follow-up. Although the low-titer animals (4x0328 and 4x506) had low HBsAg levels at baseline, declines of 48% to 60% in HBsAg still occurred in both animals during therapy (Figure 3 C). One of the low-titer animals (4x0328) was HBeAg positive at baseline and had a decline of 55% in HBeAg, while the other low-titer animal, 4x0506, was anti-HBe positive at baseline (Supplementary Table 4). The rapid decline in liver viral DNA and secreted viral antigens in the high-titer animal are consistent with an elimination of infected cells, thus we directly examined the elimination of infected cells by immunohistochemical staining of liver sections for HBV core antigen (HBcAg). In the high-titer animal, approximately 30% of hepatocytes were positive for HBcAg staining prior to therapy (Figure 3E), while on the last day of dosing when HBV DNA levels were reduced by more than 100-fold, few core positive cells were detected (Figure 3F). These results are in stark contrast to those observed in patients during therapy with nucleos(t)ide analogues which can reduce serum HBV DNA by 4 logs or greater, yet no significant reduction occurs in serum HBsAg or HBcAg positive hepatocytes over 48 weeks of therapy.20 Unfortunately, the number of HBV core antigen positive cells was too low in the low titer animals to accurately determine the degree of elimination.

Induction of Cytokines and Chemokines and Interferon-Stimulated Genes by TLR-7 Agonist GS-9620 in HBV Infected Chimpanzees

Levels of serum IFN-α and 38 other serum cytokines and chemokines were evaluated at pretreatment and at regular intervals during each treatment cycle. Pre-study IFN-α levels were below the limit of detection in animals 4x0139 and 4x0328, and these animals had dose-dependent increases in IFN-α after administration of GS-9620 at 1 mg/kg (mean 119 pg/mL) and 2 mg/kg (mean 700 pg/mL), although increases above baseline were not observed at every time point (Supplementary Table 6). The highest serum levels of IFN-α induced at the 2 mg/kg dose were 1396 and 1545 pg/mL for animals 4x0139 and 4x0328, respectively (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). The pretreatment baseline level of serum IFN-α was high in animal 4x0506 (1160 pg/mL) and was not further induced by GS-9620 treatment (Supplementary Table 9). This animal also had an elevated pretreatment baseline level of serum IFN-γ, yet GS-9620 treatment induced up to a 53-fold increase in serum levels of IP-10, a chemokine induced by IFN-α and IFN-γ. Of the other 38 cytokines and chemokines examined, during the first treatment cycle (1 mg/kg) only IL-10, MCP-3 and IL-1α were increased 5-fold above baseline, while during the second treatment cycle (2 mg/kg) 13 cytokines and chemokines were induced 5-fold or greater; with IL-7, MIP-1β, TNF-α and G-CSF being induced less than 10-fold; and IFN-α, IL-10, IP-10, MCP-1, MCP-3, IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1RA, and IL-6 being increased more than 10-fold (Supplementary Table 6).

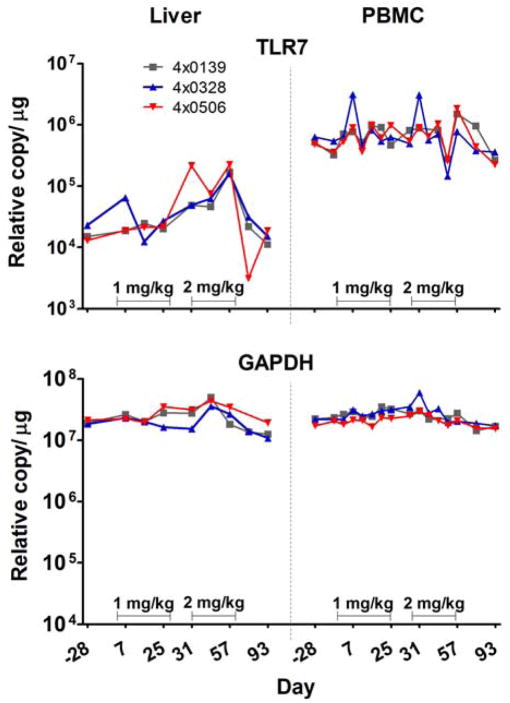

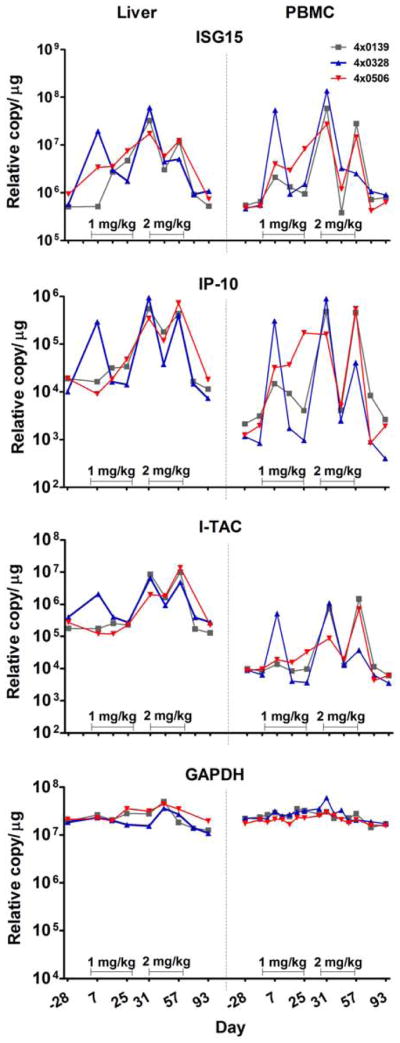

The induction of ISG transcripts (ISG15, OAS1, MX1, IP-10, and I-TAC) was evaluated in PBMC and liver biopsy samples, and each was increased in both compartments in response to GS-9620 at both the 1 and 2 mg/kg dose levels; however, induction was not consistently present at the 1 mg/kg dose level for all days evaluated. ISG transcripts are rapidly up-regulated and down-regulated within a few hours of stimulation 21. Variability in the level of response may be technical and related to the use of a single time point to measure a response that may be increasing or decreasing from the maximum value at the time of sampling (8 h post-dose), although exposure to GS-9620 may have varied to some extent after individual doses. Induction of ISGs was both more consistently present and the fold increases were greater at the 2 mg/kg dose (Figure 4 and Supplementary Tables 7, 8, 9, and 10). The group mean increase in transcript levels of the chemokine IP-10 in PBMC was 49.6- and 194-fold during the first (1 mg/kg) and second (2 mg/kg) treatment cycles, respectively (Figure 4 and Supplementary Tables 7, 8, 9, and 10). Interestingly, despite high pretreatment levels of serum IFN-α in animal 4x0506 and no apparent increase in IFN-α levels following GS-9620 administration, GS-9620 administration caused increases in ISGs in both PBMCs and the liver during both treatment cycles in this animal (Supplementary Table 10). Because TLR-7 induction in PBMCs by IFN-α was previously observed in chimpanzees,21 the induction of TLR-7 transcript was measured in this study. At pretreatment, the relative expression of TLR-7 in these chronically infected animals was 30-fold higher in PBMC than liver. TLR-7 levels were increased at multiple time points in the liver during treatment with a mean maximum induction of 11.9-fold, while increases in PBMC were minimal at most time points with a mean maximum induction 4.4-fold compared with pretreatment levels (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Induction of ISG transcripts in liver and PBMC during GS-9620 therapy in HBV infected chimpanzees.

The levels of transcripts for the ISGs; IP-10, ISG15, and I-TAC were determined by TaqMan qRT-PCR in total cell RNA from liver and PBMC during GS-9620 therapy. Animals were dosed orally three times per week for 4 weeks with 1 mg/kg or 2 mg/kg as described in the legend for Figure 3. Transcripts for the housekeeping gene GAPDH were determined as a control for non-specific stimulation. The levels of transcripts are expressed as relative copy number per μg of total cell RNA and were determined at 8 h post-dose.

Figure 5. Induction of TLR-7 transcripts in liver and PBMC of HBV infected chimpanzees during therapy with GS-9620.

Three chimpanzees chronically infected with HBV (4x0139, 4x0328 and 4x0506) were dosed orally three times per week for 4 weeks with 1 mg/kg or 2 mg/kg as described in the legend for Figure 3. Increases in TLR-7 transcripts were quantified by TaqMan qRT-PCR in PBMC and liver and are expressed as copy number per microgram of total cell RNA. The values for GAPDH are shown as a control housekeeping gene.

Activation of T Cells and NK Cells by TLR-7 GS-9620 Agonist in HBV Infected Chimpanzees

Because the stimulation of TLR-7 in pDCs can result in the subsequent activation of immune effector cells, we evaluated the activation status of peripheral blood lymphoid and NK cell subsets using cell surface CD69 expression as a biomarker. During the second treatment cycle (2 mg/kg) an increase in the percentage of CD69-expressing CD8-postive T lymphocytes, NK, and NKT cells occurred, which was maximal after the first dose (Supplementary Figure 1). Mean fold increases in the percentage of CD69-positive cells ranged from 3.6 to 5.8 (Supplementary Table 11). No significant increases occurred during the first treatment cycle at 1 mg/kg (Supplementary Table 11).

Histological changes in the liver

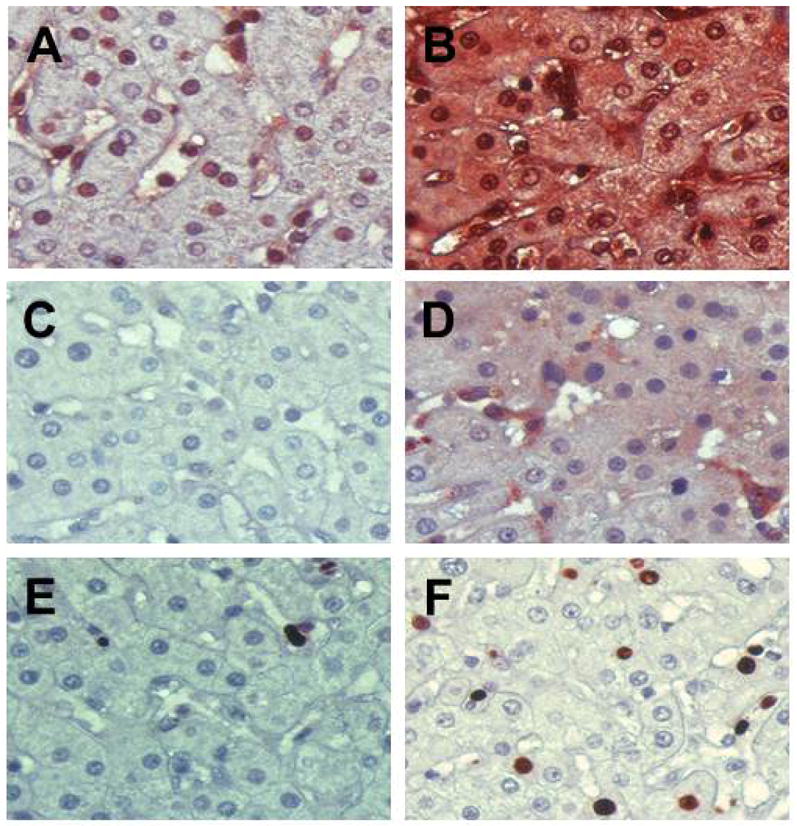

In general, the severity of hepatic inflammation in chimpanzees associated with chronic HBV infection is less than that described in humans.18 A minimal to mild primarily lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the portal tracts was present in all three animals prior to treatment. Changes noted during treatment included an increased mononuclear cell periportal infiltrate during the first treatment cycle which during the second treatment cycle extended into adjacent hepatic parenchyma and sinusoids. Additionally there was increased single cell hepatocyte apoptotosis that often was associated with minimal clusters of mononuclear cells. Histological changes noted during treatment fully reversed within 3 to 5 weeks after treatment. Immunohistochemistry of biopsies at pretreatment and on the last day of therapy demonstrated a marked increase in hepatocellular expression of ISG15 protein, a marker of IFN-α induction (Figure 6), and an increased number of hepatocytes expressing activated caspase 3, a marker for apoptosis. The latter was associated with a correlative increase in hepatocellular regeneration and proliferation as determined by expression of Ki67.

Figure 6. Reduction of HBcAg and induction of ISG15, activated caspase 3 and Ki67 in liver tissue following GS-9620 therapy.

Formalin-fixed liver sections from 4x0139 on Day -28 (A, C, E) and Day 57 (B, F) or Day 79 (D) were stained with antibodies to ISG15 (A and B) as a marker of IFN-α induction, activated caspase 3 (C and D) as a marker for apoptosis and Ki67 (E and F) as a marker for proliferation. The ISG15 antibody had some staining of nuclei in the prestudy (Day -28) as well as cytoplasmic staining in a few cells in sinusoidal spaces, while tissue from Day 57 has very intense staining across the entire section. Rare apoptotic cells positive for activated caspase 3 could be detected in the prestudy sample but were not present in this field (C), while numerous apoptotic cells are present at Day 79 (D) which appear to represent both hepatocytes and mononuclear cells in sinusoidal spaces. A few Ki67 positive hepatocytes were present in the prestudy sample (E), while positive hepatocytes were numerous on Day 57 (F).

Correlation of Viral Clearance and Elevation in Liver Enzymes

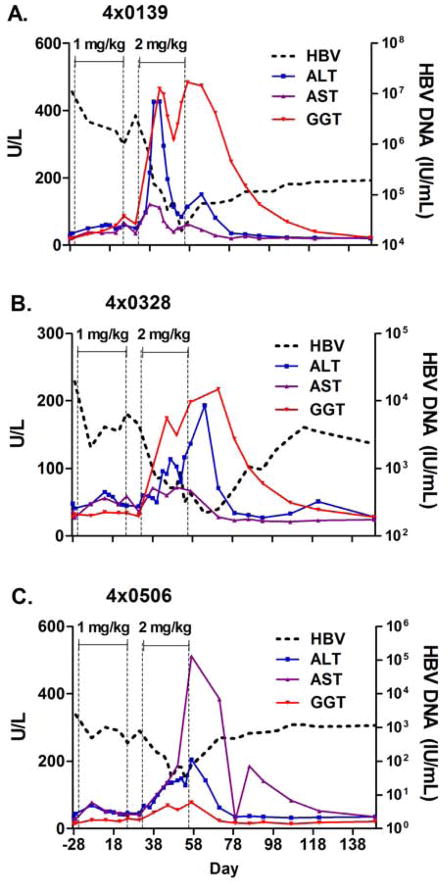

GS-9620 therapy was generally well tolerated, and no serious adverse events occurred during therapy. Clinical signs, body temperature, body weight, hematology and blood chemistries were monitored throughout the study. Body weights were mildly decreased in all three animals during the study and recovered during the post-treatment period. Adverse events in the study were limited to anemia and transient increases in serum liver enzymes. Anemia was mild to moderate in all three animals, maximal reductions in red blood cell counts were 11% to 18%, and fully or partially recovered by the end of the study (Day 121). Increases in serum levels of the liver enzymes ALT, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) occurred during the second treatment cycle (2 mg/kg) (Figure 7). In the HBV high-titer animal (animal 4x0139), a sharp increase in the level of serum ALT and GGT occurred after the first week of treatment at 2mg/kg, dosing was suspended for this animal for 1 week during which both ALT and GGT rapidly decreased, and then treatment resumed. No further increases in ALT were noted in this animal, however GGT increases were noted (Figure 4). Liver enzyme elevations fully reversed after treatment; ALT and AST returned to pretreatment baseline levels within 3 weeks and GGT by the end of the study. Mild, transient 2- to 3-fold increases in serum total bilirubin occurred at single time points in two animals (Day 43 in animal 4x0139 and Day 57 in animal 4x0506) during treatment at 2 mg/kg and were concurrent with liver enzymes increases. The transient and low level single incidence bilirubin increases were not considered adverse, but warrant monitoring in future clinical trials.

Figure 7. Increase in serum levels of liver enzymes during therapy with GS-9620 in HBV infected chimpanzees.

Serum levels (U/L; left axis) of the liver enzymes ALT, AST and GGT are shown for three HBV infected chimpanzees (4x0139, 4x0328, and 4x0506) during therapy with GS-9620 at 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg as described in the legend for Figure 3. The levels of serum HBV DNA (IU/mL) from panel A–C of Figure 3 are shown as dashed lines for reference.

Discussion

The ultimate goal of therapy for HBV chronic infection is viral eradication and cure of the underlying liver disease.22 The greatest advances in therapy have been made with nucleos(t)ide analogues that are chain terminators of the reverse transcription process.1, 23 Although nucleos(t)ide therapies reduce circulating virus to undetectable levels,24 they fail to eliminate infected hepatocytes, primarily due to the inability of this approach to eradicate the non-replicating and stable form of viral DNA in the nucleus, cccDNA. Though viral resistance was a major issue with first-generation nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors,3 newer analogues such as tenofovir appear to have little if any potential for the development of resistance during long-term therapy. 25, 26 None-the-less, the percentage of treated patients which develop loss of HBsAg is small, only 10% over five years with tenofovir and only 5% in 2 years with entecavir. Peg-IFN-α therapy suppresses viremia to undetectable levels in only a small percentage of patients during 48 weeks of therapy, yet some patients exhibit apparent cure (no rebound of viremia off of therapy, loss of HBsAg, and seroconversion with detectable antibodies to HBsAg), and the percentage of patients experiencing cure increases for several years after cessation of therapy.4–6 These data suggest that the use of improved immunomodulators such as the TLR7 agonist GS-9620 may lead to a clinically relevant improvement in therapy with a significantly higher incidence of viral eradication in patients with chronic HBV infection.

The mechanisms involved in viral clearance during acute and chronic HBV infection have been intensely examined, and though only partially understood, are believed to be associated with antiviral CD8+ T cells trafficking to the liver, the production of IFN-γ, and the induction of immune inflammatory liver disease.16 The most challenging aspect of viral clearance with HBV is the elimination of nuclear cccDNA, which is a non-replicating DNA that may exhibit stability equal to the life span of the hepatocyte. Since 40–100% of hepatocytes may be infected, a neutralizing antibody response to HBsAg is required to prevent infection of new hepatocytes that arise due to proliferation induced by hepatocyte death and/or uninfected cells arising from cytokine-induced noncytolytic elimination of the infection. Studies in transgenic mice have demonstrated that the innate immune response is capable of noncytolytic elimination of HBV replicative intermediates,27 and supportive studies in chimpanzees have observed a decrease in viral DNA prior to lymphocytic infiltration in the liver,28–30 suggestive of noncytolytic mechanisms. However, studies in woodchucks during acute infection with woodchuck hepatitis B virus have concluded that sufficient cell death occurs to account for viral clearance by cytolytic mechanisms, including loss of nuclear cccDNA due to cell death and/or cell division.31 Collectively, these data suggest that both the innate and adaptive immune responses are critical for eradication of HBV infection.

This study demonstrated a long-term benefit from a short duration (8 weeks) of therapy with the oral TLR-7 agonist GS-9620. The mean maximal reduction in serum viral load was 2.2 logs, with a continued suppression of viral DNA by a minimum of one log for 2–4 months after dosing. Viral DNA remained suppressed in the high-titer animal for a period of 1 year, while both low titer animals remained suppressed by approximately 1 log for at least one year. Consistent with stimulation of TLR-7 and activation of pDCs, the treatment induced select cytokines, including IFN-α, chemokines, and IFN-stimulated genes in PBMCs and liver. This response led to an activation of specific populations of immune effector cells with increased expression of CD69 on CD8+ T and NK cells. Activation of pDCs is known to provide licensing for cross-priming of cytotoxic lymphocytes by classical licensing and NKT cell dependent alternative licensing and TLR-activated pDC recruit and activate NK cells to become more cytotoxic in vivo. 10,11,32 GS-9620 induced a hepatic infiltration of mononuclear cells, including CD3+ and CD20+ lymphocyte, which during the second treatment cycle was also associated with single cell hepatocellular apoptosis. The reduction in serum and liver HBV DNA was associated with a reduction in serum HBeAg, HBsAg, and HBV core antigen positive hepatocytes and a concomitant increase in liver enzymes, hepatic immune cell infiltration, and hepatocellular apoptosis. Thus, the events occurring during therapy with GS-9620 are consistent with induction of antigen specific T cell responses and NK cell responses with resultant selective killing of HBV-infected cells. The direct suppression of HBV replication by transient induction of type I interferons and ISGs associated with TLR7 activation may have contributed to the response but would not account for the prolonged suppression of viral levels that was durable after cessation of treatment. The decline of serum HBsAg observed in all three animals and the apparent loss of core antigen positive hepatocytes in the high titer animal are not hallmarks of antiviral therapy with nucleos(t)ide therapy and suggest a GS-9620 mechanism beyond suppression of viral replication. The results attained in this study are consistent with results we have reported in woodchucks chronically infected with WHV wherein oral treatment with GS-9620 caused a sustained reduction in viral load, loss of WHsAg-antigen and anti-WHsAg antibody seroconversion.33 Collectively, the data support the hypothesis that TLR-7 agonism can induce immune-mediated clearance of infected cells and is a potential therapeutic approach for control or elimination of HBV infection with therapy of finite duration.

In this study, only three HBV chronically infected animals were available for the project; all were chronically infected for over two decades. This limited the scope of the study to proof-of-concept that TLR-7 stimulation could impact HBV chronic infection. We were not able to evaluate regimen optimization or combination with direct antiviral therapy nor to determine whether extended dosing at the low dose or combination with antiviral agents could result in the same reduction in viral DNA and antigen positive hepatocytes without an increase in liver enzymes. In this context, it is also important to note that the results of this study presented evidence for a “pre-systemic” TLR7 response: low doses of GS-9620 were capable of inducing an antiviral immune response at the level of the liver, PBMC, and possibly gut-associated lymphoid tissue without induction of systemic IFN-α or its side effects. At the low dose, in both uninfected and infected animals, GS-9620 induced ISGs in the liver and/or in PBMC with no detectable increase in serum levels of IFN-α. Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating whether administration of GS-9620 at “pre-systemic” dose levels provides similar antiviral benefits, alone, as recognized in this study, or in combination with direct-acting antivirals, without the side effects often associated with systemic administration of IFN-α. Identification of a well-tolerated, finite therapeutic regimen, including the possible combination of immune modulators such as GS-9620 with direct-acting antiviral agents, for the treatment and cure of chronic HBV infection in a significant and clinically relevant percentage of treated patients would be transformative for this disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by a research contract from Gilead Sciences. The Southwest National Primate Research Center is supported by an NIH primate center base grant (previously NCRR grant P51 RR13986; currently Office of Research Infrastructure Programs/OD P51 OD011133), and by Research Facilities Improvement Program Grants C06 RR 12087 and C06 RR016228.

We thank L. Notvall-Elkey and H. Lee for excellent technical assistance, the SNPRC Immunology Core Laboratory for immunological analyses, and E. Dick for pathology evaluations.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- GGT

γ-glutamyl transpeptidase

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HBcAg

HBV core antigen

- HBeAg

HBV e antigen

- HBsAg

HBV surface antigen

- IFN

interferon

- ISG

interferon-stimulated genes

- NK

natural killer

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- peg-IFN-α

pegylated-interferon-α

- SNPRC

Southwest National Primate Research Center

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Footnotes

Author contributions: REL, designed and supervised research, and equal author with DBT; BG, DC and VLH performed studies; KMB veterinarian; LG, AF, CRF and JZ, data analysis; RH, drug development; GW and DBT conceived and designed studies

Author contributions: REL, designed studies, supervised all research and co-wrote the manuscript; BG, performed studies; DC, performed studies; LG, supervised immunology laboratory and data analyses; VLH, performed Flow studies and data analyses; KMB, veterinarian that performed animal studies; AF, data analysis; CRF, data analysis; JZ, data analysis; GW, conceived and helped design studies and helped write manuscript; RH, drug development; and DBT conceived studies and equal contributor to REL in design of studies and writing manuscript.

Disclosures: AF, CRF, JZ, GW, RLH, and DBT are employees of Gilead Sciences. REL was funded by Gilead Sciences to conduct this research. No other potential conflicts exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kwon H, Lok AS. Hepatitis B therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:275–284. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonneveld MJ, Janssen HL. Chronic hepatitis B: peginterferon or nucleos(t)ide analogues? Liver Int. 2011;31 (Suppl 1):78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locarnini S, Zoulim F. Molecular genetics of HBV infection. Antivir Ther. 2010;15 (Suppl 3):3–14. doi: 10.3851/IMP1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moucari R, Korevaar A, Lada O, et al. High rates of HBsAg seroconversion in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients responding to interferon: A long-term follow-up study. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1084–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcellin P, Bonino F, Lau GKK, et al. Sustained Response of Hepatitis B e Antigen-Negative Patients 3 Years After Treatment with Peginterferon Alfa-2a. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2169–2179. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reijnders JG, Rijckborst V, Sonneveld MJ, et al. Kinetics of hepatitis B surface antigen differ between treatment with peginterferon and entecavir. J Hepatol. 2011;54:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbalat R, Ewald SE, Mouchess ML, et al. Nucleic acid recognition by the innate immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:185–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson SJ, Lindh JM, Riter TR, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce cytokines and mature in response to the TLR7 agonists, imiquimod and resiquimod. Cell Immunol. 2002;218:74–86. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ni758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh JZ, Kurche JS, Burchill MA, et al. TLR7 enables cross-presentation by multiple dendritic cell subsets through a type I IFN-dependent pathway. Blood. 2011;118:3028–3038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, et al. Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat Med. 2007;13:552–559. doi: 10.1038/nm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergmann JF, de Bruine J, Hotho DM, et al. Randomised clinical trial: anti-viral activity of ANA773, an oral inducer of endogenous interferons acting via TLR7, in chronic HCV. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:443–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pockros P, Guyager D, Patton H, et al. Oral resiquimod in chronic HCV infection: Safety and efficacy in 2 placebo-controlled, double-blind phase IIa studies. J Hepatol. 2007;47:174–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fidock MD, Souberbielle BE, Laxton C, et al. The innate immune response, clinical outcomes, and ex vivo HCV antiviral efficacy of a TLR7 agonist (PF-4878691) Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:821–829. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chisari FV, Isogawa M, Wieland SF. Pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2010;58:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehermann B, Nascimbeni M. Immunology of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nri1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason WS, Low HC, Xu C, et al. Detection of clonally expanded hepatocytes in chimpanzees with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:8396–8408. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00700-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanford RE, Feng Z, Chavez D, et al. Acute hepatitis A virus infection is associated with a limited type I interferon response and persistence of intrahepatic viral RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11223–11228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101939108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Werle-Lapostolle B, Bowden S, Locarnini S, et al. Persistence of cccDNA during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B and decline during adefovir dipivoxil therapy. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1750–1758. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanford RE, Guerra B, Lee H, et al. Genomic response to interferon-α in chimpanzees: Implications of rapid downregulation for hepatitis C kinetics. Hepatology. 2006;43:961–972. doi: 10.1002/hep.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lok AS. Hepatitis B infection: pathogenesis and management. J Hepatol. 2000;32:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80418-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Locarnini SA, Yuen L. Molecular genesis of drug-resistant and vaccine-escape HBV mutants. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:451–461. doi: 10.3851/IMP1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry CM, Simpson D. Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate In Chronic Hepatitis B. Drugs. 2009;69:2245–2256. doi: 10.2165/10482940-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snow-Lampart A, Chappell B, Curtis M, et al. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate detected after up to 144 weeks of therapy in patients monoinfected with chronic hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2011;53:763–773. doi: 10.1002/hep.24078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:132–143. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wieland SF, Guidotti LG, Chisari FV. Intrahepatic induction of alpha/beta interferon eliminates viral RNA-containing capsids in hepatitis B virus transgenic mice. J Virol. 2000;74:4165–4173. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4165-4173.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidotti LG, Rochford R, Chung J, et al. Viral clearance without destruction of infected cells during acute HBV infection. Science. 1999;284:825–829. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thimme R, Wieland S, Steiger C, et al. CD8(+) T cells mediate viral clearance and disease pathogenesis during acute hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2003;77:68–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.68-76.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wieland SF, Spangenberg HC, Thimme R, et al. Expansion and contraction of the hepatitis B virus transcriptional template in infected chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2129–2134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308478100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Summers J, Jilbert AR, Yang W, et al. Hepatocyte turnover during resolution of a transient hepadnaviral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11652–11659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Persson CM, Chambers BJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell-induced migration and activation of NK cells in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2155–2164. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menne S, Tennant BC, Liu KH, et al. Anti-viral efficacy and induction of an antibody response against surface antigen with the TLR7 agonist GS-9620 in the woodchuck model of chronic HBV infection. J Hepatol. 2011;54:S441. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.