Abstract

Background

Contemporary data on patterns of antiretroviral therapy (ART) use in the U.S. are needed to inform efforts to improve the HIV care cascade.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of patients in the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems cohort who were in HIV care in 2010 to assess ART use and outcomes, stratified by nadir CD4 count (≤350, 351-500, or >500 cells/mm3), demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, substance use, and engagement in continuous care (≥2 visits ≥3 months apart in 2010).

Results

Of 8633 patients at 7 sites who had ≥1 medical visit and ≥1 viral load (VL) in 2010, 94% had ever initiated ART, 89% were on ART, and 70% had an undetectable VL at the end of 2010. Fifty percent of ART-naïve patients had nadir CD4 counts >500 cells/mm3, but this group composed just 3% of the total population. Among patients who were ART-naïve at the time of cohort entry (N=4637), both ART initiation and viral suppression were strongly associated with nadir CD4 count. Comparing 2009 and 2010, the percentages of patients with viral suppression among those with nadir CD4 counts 351-500 and >500 cells/mm3 were 44% vs. 57% and 25% vs. 33%, respectively. Engagement in care was the only factor consistently associated with ART use and viral suppression across nadir CD4 count strata.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that ART use and viral suppression among persons in HIV care may be more common than estimated in some prior studies and increased from 2009 to 2010.

Keywords: Antiretroviral Therapy, Highly Active; HIV Infections/drug therapy; HIV Infections/prevention & control; Patient Acceptance of Health Care/statistics & numerical data; United States

INTRODUCTION

Suppression of the plasma HIV RNA level is a key goal of medical care for persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and is increasingly a focus of public health efforts to prevent HIV transmission.1 National estimates suggest that only 19-28% of PLWHA in the U.S have achieved viral suppression2-5 due to compounding breakdowns at each step in the HIV care cascade. However, such estimates are imprecise, reflecting incomplete nationwide surveillance data on viral suppression and the inability of surveillance systems to ascertain ART use. While public health authorities can estimate levels of viral suppression using laboratory reporting of HIV RNA [viral load (VL)] test results, these estimates are limited in many areas by incomplete reporting and by uncertainty about which persons determined to be HIV-infected in a surveillance area continue to reside in that area.6 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) estimates ART use with probability-based sampling of HIV care facilities and patients in care during the first four months of the year, but to date, MMP data have been limited by incomplete provider and patient participation.7

In addition to the importance of contemporary data on ART use and viral suppression, a clearer understanding of how ART uptake varies among PLWHA in different nadir CD4 count groups is important for monitoring the effect of changes in treatment guidelines and the impact of reductions in state AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, identifying disparities in treatment access, and projecting resources required to expand ART use among PLWHA in the U.S. Little is known about the size and composition of the population of persons in HIV care who have nadir CD4 counts >500 cells/mm3, a group of particular interest in the context of revised guidelines for ART initiation and increasing optimism about the potential for “test and treat” strategies to decrease the size of the HIV epidemic. Furthermore, contemporary estimates of ART use and viral suppression among persons in HIV care can aid studies to assess the impact of expanded health insurance coverage among PLWHA in the U.S. under the Affordable Care Act.

The primary goal of this study was to estimate the proportion of persons who have initiated ART, are on continuing ART, and have viral suppression in a nationally distributed cohort of persons in HIV care in the U.S. Our secondary objectives were to compare ART use and viral suppression by nadir CD4 count group and to determine factors associated with being ART-naive, discontinuing ART, and/or having detectable viremia despite continuing ART use, stratified by nadir CD4 count.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional study of patients in the Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR) Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) cohort, which includes over 25,000 HIV-infected adults in care dating back to 1995 at eight university-affiliated CFARs. The methodology and characteristics of the CNICS cohort are described in detail elsewhere.8 Briefly, CNICS is a dynamic observational cohort with approximately 1400 new patients enrolling and 13% of existing patients leaving care each year. The CNICS data repository systematically captures information from electronic health records (EHRs) and pharmacy systems at each CNICS site. Validation of data occurs in three phases: at the individual sites prior to data transmission, at the time of data submission to the Data Management Core prior to insertion into the central repository, and through the use of automated validation procedures at the time of data integration. Data then undergo an extensive set of quality assurance procedures and data quality issues are reported to CNICS sites to investigate and correct.

Our objective was to assess historical and current ART use among patients in care at the end of 2010, one year after the publication of HIV treatment guidelines recommending ART initiation before progression of the CD4 count to <500 cells/mm3. The study population included patients who were in care (≥ 1 medical visit) and had ≥ 1 VL measurement in 2010. In order to focus on a population in which clinicians and patients had sufficient time to carry out treatment decisions in response to CD4 counts <500 cells/mm3, we limited the study population to patients who entered the cohort ≥9 months prior to the end of 2010. We excluded patients who entered care prior to the combination ART era, defined as before January 1, 1997 (N=1311); women who appeared to be receiving ART for perinatal treatment at the time of their most recent regimen (N=20); and patients from one CNICS clinic site due to incomplete data (N=914).

We analyzed the proportion of patients ever on ART, on continuing ART, and with viral suppression at the end of 2010. We classified subjects as “ever on ART” if they had initiated ART on or before December 31, 2010 and as “on continuing ART” if they had initiated ART and had no documentation of discontinuing all ART as of December 31, 2010. The latter group included patients who discontinued then restarted ART as long as they continued a regimen through the end of 2010. ART initiation and cessation dates defined by the treating provider in the EHR and in pharmacy prescription fill/refill data were validated at the individual sites and centrally through chart review and applications to monitor data quality. During our analysis the Data Management Core sent lists of patients who had undetectable viral loads but no corresponding ART data to each CNICS site for investigation. The sites responded with corrected ART data or confirmation of elite controller status for each case.

For analysis of viral suppression, we identified the last recorded VL for each patient and defined suppression as any result below the level of quantitation of the assay. We focused on undetectable VL as the primary outcome for viral suppression because it is the primary clinical goal of ART and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended indicator.9 We separately report the proportion of patients with VL ≤200 copies/mL to facilitate comparison with other reports.4, 5, 10 We did not exclude patients who had viral suppression in the absence of ART initiation from this analysis because our goal was to assess viral suppression in the entire study population, regardless of the underlying mechanism of suppression.

We conducted a subset analysis stratifying each outcome (ever on ART, continuing ART, and viral suppression) by nadir CD4 count. We grouped subjects by nadir CD4 count ≤350, 351-500, or >500 cells/mm3 based on the relevance of these categories to U.S. HIV treatment guidelines for ART initiation. We limited analysis of nadir CD4 count to patients who were ART-naïve at the time of entry into the CNICS cohort since pretreatment CD4 counts are not uniformly available in patients who were treatment experienced at entry. We identified the nadir CD4 count for each patient as of March 31, 2010. We conducted a repeat cross-sectional analysis in order to compare patterns of ART use and viral suppression in 2009 and 2010, using the same methods as those described above to assess the outcomes at the end of 2009 among patients who had entered the cohort prior to March 31, 2009.

For bivariate comparisons of ART use and viral suppression by patient subpopulation, we used Pearson’s chi-square tests. We selected independent variables a priori, based on previous demonstrations of association with ART initiation, adherence and/or viral suppression,11-14 including age, sex, race/ethnicity, HIV risk group, engagement in HIV care, psychiatric disorders and substance abuse. We categorized HIV risk group as men who have sex with men (MSM) [including injection drug using (IDU) MSM], IDU, non-IDU heterosexual, and other. We defined engagement in continuous care as ≥ 2 visits ≥ 3 months apart in 2010, the measure recommended by IOM9 and the U.S. National HIV/AIDS Strategy.15 We analyzed psychiatric and substance use disorders diagnosed by treating providers. These data are not available uniformly from all CNICS sites, and we limited analysis of these variables to patients from reporting sites. We used the methodology validated by Tegger and colleagues16 to categorize psychiatric comorbidities and substance use into separate, mutually exclusive, hierarchical groups: (1) psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, and /or personality disorders with or without depression and anxiety, (2) depression and/or anxiety only, (3) no mental illness. We categorized substance use into five mutually exclusive, hierarchical groups: (1) opiates with or without other drugs, (2) amphetamines with or without other drugs, (3) cocaine with or without alcohol, (4) alcohol only, or (5) no substance use.16 Patients at CNICS sites that report these data who did not have a diagnosis were classified as having “none of the above” diagnoses. We were unable to distinguish treated from untreated psychiatric disorders or active from past substance use.

We used Poisson regression clustered by clinic site for multivariate analysis of three outcome measures, stratified by nadir CD4 count. For these models we defined the outcomes as “failure” isolated to individual steps in the care cascade: ART non-initiation, ART discontinuation, and detectable viremia despite continuing ART use. Poisson regression allows for calculation of estimated relative risks instead of odds ratios in cohort data.17 We estimated prevalence ratios (PR) of each outcome at the end of 2010. Clustered analysis adjusts for correlation between results from individual sites, thereby accounting for unmeasured factors associated with potentially different ART prescribing practices. We constructed a model for each of the three outcome measures for each of the nadir CD4 groups. Our initial models included all of the independent variables we defined a priori, except for psychiatric and substance abuse since not all sites reported this information, and we retained all variables in the final model. We then explored the potential effect of length of time in care on ART initiation, and because this was significantly associated with ART initiation in one nadir CD4 group, the final models include adjustment for years in care at a CNICS site. We used Stata 10.1 for all analyses (StataCorp, TX). Institutional review boards (IRB) at each university approved data collection procedures, and the University of Washington IRB judged this analysis to be exempt from review due to the use of de-identified data.

RESULTS

ART Use and Outcomes among Patients in Care in 2010

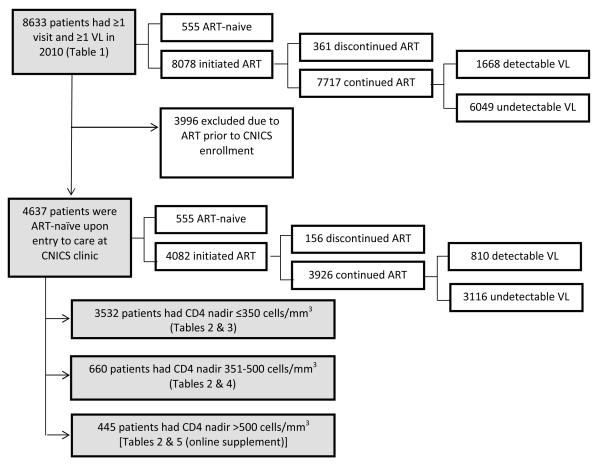

The study population included 8633 persons from seven CNICS sites (range 720 −1,735 patients per site) who met inclusion criteria for active HIV medical care in 2010 (Figure 1). As of December 31, 2010, these patients had been in care at CNICS sites for a median of 60 months [interquartile range (IQR): 30-100 months]. The inclusion criteria of ≥1 visit and ≥1 VL in 2010 excluded 1312 persons (13%) compared to the population of patients with ≥1 visit and ≥1 VL anytime in either 2009 or 2010 (N=9945).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study population and primary outcome measures. Shaded boxes indicate populations described in the manuscript tables. ART, antiretroviral therapy. VL, viral load.

At the end of 2010, 94% of patients had ever been on ART (range: 92-95% across sites), 89% were on continuing ART (range: 88-91%), and 70% had viral suppression (range: 56-85%) (Table 1). By the less restrictive definition of VL ≤200 copies/mL, 79% (range: 71-86%) had viral suppression. Restricting the analysis to patients who had been on ART ≥6 months, the prevalence of viral suppression was similar in patients on ART <1 year (76%) compared to >1 year (78%; p=0.45). The distribution of the 555 patients who remained ART-naïve at the end of 2010 by nadir CD4 count was as follows: 102 (18%) ≤350 cells/mm3, 177 (32%) 351-500 cells/mm3, and 276 (50%) >500 cells/mm3. Approximately 1% of the study population (N=70) had undetectable VL in the absence of documented ART initiation, of whom 16 (23%) had a nadir CD4 count ≤350 cells/mm3, 18 (26%) 351-500 cells/mm3, and 36 (51%) >500 cells/mm3.

Table 1.

History of antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation and continuing ART use and viral suppression at the end of 2010 among patients who received care at a CNICS clinic in 2010 (N=8633)

| Percent | Percent on | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Ever on | Continuing | with viral | |

| (% of total) | ART | ART | suppression | |

| Total Population | 8633 (100) | 94 | 89 | 70 |

| Gender1 | ||||

| Male | 7170 (83) | 94 | 90 | 70 |

| Female | 1372 (16) | 92* | 86* | 66* |

| Transgender Women | 79 (1) | 90 | 89 | 62 |

| Transgender Men | 12 (<1) | 100 | 100 | 75 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18-29 | 750 (9) | 81* | 76* | 56* |

| 30-39 | 1799 (21) | 91* | 87* | 64* |

| 40-49 | 3516 (41) | 95* | 91* | 71* |

| ≥50 | 2568 (30) | 97 | 93 | 77 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4222 (49) | 94 | 90 | 73 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2658 (31) | 92* | 86* | 62* |

| Hispanic | 1243 (14) | 95 | 92 | 74 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 185 (2) | 94 | 91 | 74 |

| American Indian | 68 (1) | 96 | 90 | 71 |

| Multiple/Other | 184 (2) | 92 | 89 | 79 |

| Missing | 73 (1) | 92 | 84 | 81 |

| HIV Risk Category | ||||

| MSM | 5365 (62) | 94 | 90* | 72* |

| IDU (Non-MSM) | 820 (10) | 94 | 87 | 66 |

| Heterosexual | 2131 (25) | 93 | 88 | 66 |

| Other | 155 (2) | 96 | 88 | 66 |

| Missing | 162 (2) | 95 | 93 | 76* |

| Continuous Care in 2010 | ||||

| Yes | 7237 (84) | 94 | 91 | 73 |

| No | 1396 (16) | 90* | 81* | 55* |

NOTE. Asterisk (*) denotes p<0.05 in Pearson chi-square tests. Reference groups in each category were male gender, ≥50 years of age, Non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity, heterosexual HIV risk category, and engaged in continuous care.

In bivariate analysis, viral suppression was less common among women compared to men (p<0.001); patients <50 compared to >50 years of age (p<0.001 for all comparisons); non-Hispanic blacks compared to non-Hispanic whites (p<0.001); and patients not engaged compared to those engaged in continuous care (p<0.001). Viral suppression was more common in MSM than heterosexuals and IDU (p<0.001). Comparing patient subgroups, differences in the proportion of patients who had initiated ART were generally smaller than differences in the proportion of patients with viral suppression. For example, 92% of non-Hispanic blacks and 94% of non-Hispanic whites had initiated ART, but only 62% of non-Hispanic blacks had viral suppression compared to 73% of non-Hispanic whites.

ART Use and Outcomes in Patients who were ART-naïve at the Time of Entry into Care

Table 2 shows ART status and viral suppression, stratified by nadir CD4 count, in the 4637 patients who were ART-naïve at the time of entry into care at a CNICS site. These patients had been in care at CNICS sites for a median of 60 (IQR: 31-99) months. Initial CD4 counts after entry to care were ≤350 cells/mm3 in 49%, 350-500 cells/mm3 in 22%, and >500 cells/mm3 in 28% of patients. At the end of 2010, 88% of patients had initiated ART, 85% were on continuing ART, and 67% had viral suppression (76% had VL ≤ 200 copies/mL). More patients with nadir CD4 counts ≤ 350 cells/mm3 had initiated ART and were on continuing ART (97% and 94%, respectively) compared to patients with nadir CD4 counts 351-500 cells/mm3 (73% and 70%, respectively) and >500 cells/mm3 (38% and 36%, respectively) (p<0.001 for all comparisons). Similarly, the proportion of patients with viral suppression, on or off ART, varied by nadir CD4 group (≤350 cells/mm3: 73%; 351-500 cells/mm3: 57%; >500 cells/mm3: 33%; p<0.001). The association of lower nadir CD4 count with higher levels of ART use and viral suppression was evident across all subgroups presented in Table 2. Among patients on ART for ≥6 months, there was a trend toward higher rates of suppression in patients who initiated ART with higher CD4 counts [(≤350 cells/mm3, 79%; 351-500 cells/mm3, 82%; >500 cells/mm3, 86% (p=0.095)].

Table 2.

ART initiation (“Ever”), continued ART use (“On”), and viral suppression (VS) among CNICS patients in 2009 (N=4265) and 2010 (N=4637) who were ART-naïve at the time of cohort entry

| CD4 nadir ≤350 cells/mm3 | CD4 nadir 351-500 cells/mm3 | CD4 nadir >500 cells/mm3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| N | % | % | % | N | % | % | % | N | % | % | % | |

| (% total) | Ever | On | VS | (% total) | Ever | On | VS | (% total) | Ever | On | VS | |

| Total in 2009 | 3292 (100) |

96 | 91 | 74 | 563 (100) | 63 | 58 | 44 | 410 (100) | 27 | 25 | 25 |

| Total in 20101 | 3532 (100) |

97 | 94 | 73 | 660 (100) | 73 | 70 | 57 | 445 (100) | 38 | 36 | 33 |

| Gender2 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 2898 (82) | 97 | 94 | 75 | 560 (85) | 73 | 70 | 57 | 363 (82) | 43 | 41 | 35 |

| Female | 599 (17) | 97 | 92 | 68* | 98 (15) | 71 | 65 | 55 | 76 (17) | 17* | 14* | 263 |

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||

| 18-29 | 304 (9) | 95* | 89* | 64* | 142 (22) | 61* | 59* | 46* | 116 (26) | 42 | 41 | 33 |

| 30-39 | 850 (24) | 96* | 93 | 70* | 208 (32) | 75 | 72 | 57 | 122 (27) | 37 | 35 | 30 |

| 40-49 | 1400 (40) | 98 | 94 | 75 | 197 (30) | 78 | 72 | 61 | 140 (31) | 37 | 35 | 34 |

| ≥50 | 978 (28) | 98 | 95 | 77 | 113 (17) | 79 | 76 | 62 | 67 (15) | 34 | 28 | 36 |

| Race/Ethnicity2 | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1618 (46) | 97 | 94 | 76 | 341 (52) | 77 | 74 | 60 | 202 (45) | 39 | 37 | 32 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1164 (33) | 96 | 91* | 65* | 187 (28) | 65* | 60* | 51* | 157 (35) | 34 | 30 | 35 |

| Hispanic | 520 (15) | 98 | 96 | 79 | 86 (13) | 76 | 73 | 52 | 55 (12) | 47 | 45 | 29 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 104 (3) | 99 | 97 | 79 | 17 (3) | 71 | 71 | 59 | 11 (2) | 45 | 45 | 36 |

| HIV Risk Category2 | ||||||||||||

| MSM | 2079 (59) | 97 | 94 | 77* | 444 (67) | 74 | 71 | 59 | 302 (68) | 43* | 41* | 34 |

| IDU (non-MSM) | 349 (10) | 96 | 90* | 65 | 45 (7) | 62 | 58 | 42 | 25 (6) | 24 | 24 | 20 |

| Heterosexual | 986 (28) | 97 | 94 | 70 | 147 (22) | 73 | 68 | 56 | 105 (24) | 24 | 20 | 29 |

| Continuous Care in 2010 | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 2978 (84) | 98 | 95 | 76 | 542 (82) | 77 | 74 | 62 | 353 (79) | 40 | 38 | 36 |

| No | 554 (16) | 95* | 86* | 59* | 118 (18) | 58* | 52* | 33* | 92 (21) | 29 | 26* | 21* |

| Total from sites reporting | ||||||||||||

| psychiatric and substance abuse data (N=3287) |

2490 (100) |

471 (100) | 326 (100) | |||||||||

| Mental Illness | ||||||||||||

| Psychosis, BPD or PD | 393 (16) | 96 | 90 | 70 | 74 (16) | 77 | 72 | 53 | 52 (16) | 27 | 21* | 35 |

| Depression/Anxiety | 1623 (65) | 97* | 93 | 73 | 306 (65) | 78 | 75 | 59 | 195 (60) | 45 | 43 | 32 |

| None of the above | 474 (19) | 96 | 92 | 70 | 91 (19) | 68 | 67 | 54 | 79 (24) | 41 | 38 | 42 |

| Substance Abuse | ||||||||||||

| Opiates | 67 (3) | 97 | 91 | 57* | 14 (3) | 71 | 71 | 57 | 9 (3) | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Amphetamines | 122 (5) | 95 | 93 | 67 | 32 (7) | 78 | 75 | 56 | 15 (5) | 47 | 47 | 20 |

| Cocaine | 239 (10) | 94* | 87* | 59* | 51 (11) | 69 | 65 | 47 | 35 (11) | 37 | 37 | 34 |

| At-risk alcohol | 191 (8) | 97 | 93 | 71 | 40 (8) | 78 | 70 | 53 | 28 (9) | 25 | 25 | 29 |

| None of the above | 1871 (75) | 97 | 94 | 75 | 334 (71) | 77 | 74 | 59 | 239 (73) | 44 | 41 | 37 |

All following rows are CNICS patients in 2010

Categories with <50 patients in any stratum omitted from table (transgender male and female; American Indian, multiple, “other” and missing race; and “other” and missing HIV risk factor). Non-Hispanic patients who reported race as “other” were also omitted from this table.

Proportion suppressed was higher that proportion on ART due to ART discontinuation occurring after the last recorded VL in 2010 or viral suppression in the absence of ART initiation.

NOTE. Asterisk (*) denotes p<0.05 in Pearson chi-square tests. Reference groups were male gender, ≥50 years of age, Non- Hispanic white race/ethnicity, heterosexual HIV risk category, engaged in continuous care, and “none of the above” for mental illness and substance abuse.

Of 4265 patients who met inclusion criteria for analysis of ART initiation at the end of 2009, 85% had ever been on ART, 80% were on continuing ART, and 65% had viral suppression. The proportions of patients who had ever initiated ART, were on ART and with viral suppression were higher among those with nadir CD4 counts of 351-500 and >500 cells/mm3 in 2010 compared to 2009 (Table 2).

Engagement in Continuous Care

Overall, approximately 16% of the entire study population (N=8633) and of the patients who were ART-naïve at cohort entry (N=4637) were not engaged in continuous care. Among those ART-naïve at cohort entry, non-engagement was more common among those with higher nadir CD4 counts (≤350 cells/mm3: 16%; 351-500 cells/mm3: 18%; >500 cells/mm3: 21%; p=0.02). Adjusting for nadir CD4 count, engagement in care was the single factor most strongly and consistently associated with ART use and viral suppression. Younger age was associated with poorer care engagement [age 18-29: PR 0.94 (95% CI: 0.91 – 0.97); age 30-39: PR 0.96 (95% CI: 0.94 – 0.97) compared to patients >50 years of age], as was non-Hispanic black race [PR 0.97 (95% CI: 0.95 – 0.996)], controlling for nadir CD4 count.

Factors Associated with Failure to Initiate ART, Continue ART, and Achieve Viral Suppression

Tables 3, 4, and the online supplemental table 5 present the results of multivariate analyses assessing the association of independent variables with ART non-initiation, ART discontinuation among patients who initiated ART, and detectable viremia in patients on continuing ART, stratified by nadir CD4 count, among patients who were ART-naïve at the time of entry to care (N=4637). Failure to engage in continuous care was consistently associated with viremia across all nadir CD4 count groups and with lower levels of ART initiation and ongoing use in patients with nadir CD4 counts ≤500 cells/mm3. Otherwise, associations were heterogeneous across nadir CD4 groups. In the population with the strongest indication for treatment (CD4 counts <350 cells/mm3), failure at each step was generally higher among young people and African Americans though not all PR associating these factors with failures were significant.

Table 3.

Factors associated with not initiating ART, discontinuing ART and having detectable viremia despite continuing ART among patients with nadir CD4 counts ≤ 350 cells/mm3.

| Variable | Adjusted PR1 of failure to initiate ART |

Adjusted PR1 of ART discontinuation, among patients who initiated ART |

of Adjusted PR1 of detectable viremia, among patients on continuing ART |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=3532) | (N=3430) | (N=3308) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | REF | REF | REF |

| Female | 1.28 (0.60 – 2.71) | 1.28 (0.91 – 1.82) | 0.95 (0.83 – 1.08) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18-29 | 1.48 (0.65 – 3.40) | 2.10 (1.01–4.39) | 1.46 (1.18–1.82) |

| 30-39 | 1.49 (0.70 – 3.17) | 1.30 (0.82 – 2.07) | 1.33 (1.07–1.64) |

| 40-49 | 1.15 (0.57 – 2.32) | 1.42 (0.88 – 2.28) | 1.12 (0.95 – 1.31) |

| ≥50 | REF | REF | REF |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF | REF |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.39 (0.82 – 2.33) | 1.55 (0.91 – 2.65) | 1.46 (1.19–1.79) |

| Hispanic | 0.58 (0.30 – 1.09) | 0.84 (0.91 – 2.65) | 0.88 (0.65 – 1.19) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

0.29 (0.04 – 2.12) | 0.60 (0.13 – 2.72) | 0.89 (0.67 – 1.19) |

| HIV Risk Category | |||

| MSM | 1.28 (0.53 – 3.06) | 1.06 (0.73 – 1.54) | 0.80 (0.62 – 1.04) |

| IDU (non-MSM) | 2.08 (0.98 – 4.39) | 2.16 (1.29–3.60) | 1.28 (0.89 – 1.86) |

| Heterosexual | REF | REF | REF |

| Continuous care in 2010 |

|||

| Yes | REF | REF | REF |

| No | 2.25 (1.34–3.78) | 3.35 (2.52–4.46) | 1.55 (1.26–1.89) |

| Years in care2 | 0.83 (0.75–0.93) | 1.01 (0.96 – 1.07) | 0.98 (0.95 – 1.02) |

REF, reference group. Bold typeface signifies p-value ≤ 0.05.

From Poisson regression clustered by site, adjusted for all other factors in table.

PR is per year in care at CNICS site

Table 4.

Factors associated with not initiating ART, discontinuing ART and having detectable viremia among patients with nadir CD4 counts 351-500 cells/mm3.

| Variable | Adjusted PR1 of | Adjusted PR1 of ART | Adjusted PR1 of |

|---|---|---|---|

| failure to initiate ART | discontinuation, | detectable viremia, | |

| among patients who | among patients on | ||

| initiated ART | contining ART | ||

| (N=660) | (N=483) | (N=460) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | REF | REF | REF |

| Female | 1.05 (0.69 – 1.58) | 1.47 (0.30 – 7.15) | 0.87 (0.43 – 1.76) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18-29 | 1.51 (0.87 – 2.63) | 0.82 (0.14 – 4.67) | 1.23 (0.86 – 1.77) |

| 30-39 | 1.10 (0.61 – 1.99) | 1.42 (0.29 – 7.04) | 1.10 (0.54 – 2.25) |

| 40-49 | 1.07 (0.68 – 1.68) | 2.64 (0.93 – 7.45) | 0.96 (0.52 – 1.75) |

| ≥50 | REF | REF | REF |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF | REF |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.45 (0.23 – 1.71) | 2.14 (1.06–4.31) | 0.97 (0.80 – 1.17) |

| Hispanic | 0.99 (0.68 – 1.68) | 0.85 (0.23 – 3.19) | 1.07 (0.69 – 1.64) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander |

1.25 (0.53 – 2.95) | NC | 0.68 (0.20 – 2.27) |

| HIV Risk Category | |||

| MSM | 1.02 (0.69 – 1.52) | 1.19 (0.16 – 8.64) | 0.81 (0.50 – 1.32) |

| IDU (non-MSM) | 1.56 (0.98 – 2.71) | 1.91 (0.39 – 9.38) | 1.33 (0.85 – 2.07) |

| Heterosexual | REF | REF | REF |

| Continuous care in 2010 |

|||

| Yes | REF | REF | REF |

| No | 1.79 (1.31–2.44) | 2.29(1.08–4.88) | 1.94 (1.08–3.48) |

| Years in care2 | 0.95 (0.88 – 1.01) | 1.08 (0.97 – 1.19) | 0.96 (0.88 – 1.04) |

REF, reference group; NC, not calculable. Bold typeface signifies p-value ≤ 0.05.

From Poisson regression clustered by site, adjusted for all other factors in table

PR is per year in care at CNICS site

DISCUSSION

We found that, among patients in HIV care at one of seven CNICS sites during 2010, 94% had ever initiated ART, 89% were on continuing ART, and 70% had viral suppression at the end of 2010. Treatment initiation increased from 2009 to 2010 in patients with a nadir CD4 count >350 cells/mm3, including those with a nadir CD4 count >500 cells/mm3. This demonstrates a movement toward earlier ART initiation in practice likely due, in part, to revised treatment guidelines in 2009. ART-naïve patients with a nadir CD4 count >500 cells/mm3 accounted for just 3% of the total population, indicating that the most recent revision of U.S. HIV/AIDS treatment guidelines recommending ART initiation regardless of CD4 count likely only slightly enlarged the number of patients for whom ART initiation is recommended.

Our findings are broadly consistent with those of other recent studies of ART use and viral suppression among persons in HIV care in the U.S. An analysis from the CDC MMP found that, among a nationwide cohort of persons, 89% were prescribed ART in the past 12 months and 71% had a VL ≤200 copies/mL.10 We found 89% ART use and 79% viral suppression using comparable definitions. Marks and colleagues reported that 62% of persons retained in care in six HIV outpatient clinics achieved viral suppression (<75 copies/mL), and we found 70% viral suppression using a comparable definition.18 Programmatic data from the In+Care Project show a mean of 69% viral suppression in reporting populations,19 and client-level data from the Ryan White Services Report show that 85% of clients were prescribed ART and 76% had viral suppression.20 Taken together, the consistency of these data strongly suggest that 60-80% of persons in HIV care have viral suppression and stand in contrast to earlier estimates of 48-60% viral suppression among persons in care.2, 3 In turn, the data suggest that the proportion of persons with viral suppression among all PLWHA in the U.S. – which is based in part on estimates of viral suppression among those in care-likely exceeds or is at the upper end of the range of previously published estimates of 19-28%.

ART initiation will likely increase in response to current U.S. HIV/AIDS treatment guidelines recommending ART for all PLWHA. However, half of the patients in CNICS who had not initiated ART by the end of 2010 had a nadir CD4 count ≤500 cells/mm3, the threshold at which initiation was uniformly recommended under treatment guidelines active at the time. The strongest and most consistent predictor of ART non-initiation, ART discontinuation, and failure to achieve viral suppression was a lack of engagement in continuous HIV care. This is consistent with the findings of several previous studies21, 22 and reinforces the need to better understand barriers to sustained engagement in care. Younger patients and patients with higher nadir CD4 counts were less likely to be engaged in continuous HIV care. This suggests that patients’ perceived lack of need for HIV care may be an important barrier to engagement, but may also reflect provider-related decisions to schedule visits less frequently. Future CNICS studies will include patient-reported measures of mental illness and current substance use to better define the impact of these factors on care engagement and viral suppression.

Although race/ethnicity and female sex were not consistent independent predictors of lower ART use and viral suppression, women and non-Hispanic blacks had lower rates of ART initiation, ART continuation, and viral suppression. These disparities, particularly in the context of disproportionate risk for HIV infection and late HIV diagnosis among non-Hispanic blacks,23, 24 highlight the ongoing imperative to address disparities at every step in the HIV care cascade.

The greatest strength of our study is that it provides precise contemporary information on key steps in the HIV care cascade in the U.S. using data from a large, geographically diverse population of persons in HIV care. CNICS data include visit dates, allowing us to directly ascertain engagement in continuous care, and all CNICS data undergo rigorous quality assurance procedures. However, our study was limited to patients who had ≥1 visit in 2010 and thus does not provide information about persons who are completely out of care. Indeed, 13% of the population in care in 2009 was not seen in 2010, and we do not have data on their care and viral suppression status in 2010. The CNICS cohort is composed of patients receiving care at university-affiliated HIV clinics that may not be representative of HIV care throughout the U.S, but the similarity of our findings to those of MMP, which samples patients from a diverse array of HIV clinics, suggests that this is not a major limitation. We may have misclassified ART use by assuming continued therapy in the absence of documented discontinuation, but such misclassification would not have affected our estimates of virologic suppression.

In conclusion, we found that the vast majority of persons in active HIV medical care in a nationally distributed cohort in 2010 have initiated ART and that approximately 70% have viral suppression. Along with other recent reports, these findings suggest that viral suppression may be more common among persons in HIV care compared with earlier studies. Our study indicates that the increase in demand for ART under guidelines recommending ART initiation regardless of CD4 count is likely to be relatively small and highlights the need to work toward increasing engagement in HIV care.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Jim Hughes and Ms. Kathy Thomas for statistical advice and all CNICS sites for contributing data to the study.

Sources of Support: This research was supported by NIH grants T32 AI07140-31 and K23MH090923 to JD and K23MH082641-05 to MJM, the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757) which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA; the UAB Center for AIDS Research (P30-AI027767) and by an NIH grant for the CFAR-Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (R24AI067039).

Footnotes

Note: These findings were presented in part at the 48th Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America in Vancouver, B.C., 2010.

Potential Conflicts of Interest/Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: Dr. Mugavero has received grants and/or consultancy fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Foundation, Tibotec Therapeutics, Pfizer, Definicare, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Eron has received grants and/or consultancy fees from Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Glaxo-Smith-Klein/ViiV, Gilead Sciences, and Tibotec Therapeutics/Janssen. Dr. Golden has received free medications and test kits for research studies from Pfizer and Genprobe.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns DN, Dieffenbach CW, Vermund SH. Rethinking prevention of HIV type 1 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:725–731. doi: 10.1086/655889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall HI, Frazer EL, Rhodes P, et al. Continuum of HIV care: differences in care and treatment by sex and race/ethnicity in the United States. Presented at: XIX International AIDS Conference; Washington, DC. 2012. [FRLBX05] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment – United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1618–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dombrowski JC, Kent JB, Buskin SE, Stekler JD, Golden MR. Population-Based Metrics for the Timing of HIV Diagnosis, Engagement in HIV Care, and Virologic Suppression. AIDS. 2012;26:77–86. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834dcee9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair JM, McNaghten AD, Frazier EL, Skarbinski J, Huang P, Heffelfinger JD. Clinical and behavioral characteristics of adults receiving medical care for HIV infection --- Medical Monitoring Project, United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitahata MM, Rodriguez B, Haubrich R, et al. Cohort profile: the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:948–955. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine . Monitoring HIV care in the United States: indicators and data systems. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skarbinski J, Johnson C, Frazier E, Beer L, Valverde E, Heffelfinger J. Nationally representative estimates of the number of HIV+ adults who received medical care, were prescribed ART, and achieved viral suppression - Medical Monitoring Project, 2009 to 2010: US [Abstract 138]. Presented at: 12th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, WA. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lillie-Blanton M, Stone VE, Snow Jones A, et al. Association of race, substance abuse, and health insurance coverage with use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected women, 2005. Am J Public Health. 2009;100:1493–1499. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNaghten AD, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, Jones JL. Differences in prescription of antiretroviral therapy in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32:499–505. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Allison JJ, et al. Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: do missed visits matter? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5c37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pence BW, Ostermann J, Kumar V, Whetten K, Thielman N, Mugavero MJ. The influence of psychosocial characteristics and race/ethnicity on the use, duration, and success of antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:194–201. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815ace7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White House Office of National AIDS Policy . Federal Implementation Plan. The White House; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tegger MK, Crane HM, Tapia KA, Uldall KK, Holte SE, Kitahata MM. The effect of mental illness, substance use, and treatment for depression on the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:233–243. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:940–943. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care: do more than 19% of HIV-infected persons in the US have undetectable viral load? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;11:1168–1169. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir678. author’s reply 1169-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Quality Center [Accessed September 21, 2012];NQC News | in+care Campaign Update. NQC e-Newsletter. 2012 5(47) Available at: http://archive.constantcontact.com/fs034/1105430511667/archive/1109781861111.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.HRSA/HAB [Accessed September 21, 2012];HIV Performance Measure Module Update. HAB Information E-mail. 2012 15(6) Available at: http://health.groups.yahoo.com/group/hivsnp/message/11499. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mugavero MJ, Lin HY, Willig JH, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:248–256. doi: 10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC, Jr., et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Disparities in diagnoses of HIV infection between blacks/African Americans and other racial/ethnic populations--37 states, 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen M, Rhodes PH, Hall IH, Kilmarx PH, Branson BM, Valleroy LA. Prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection among persons aged >/=13 years--National HIV Surveillance System, United States, 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(Suppl):57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.