Abstract

Objective

Nicotine dependence frequently co-occurs with subsyndromal and pathological levels of gambling. The relationship of nicotine dependence, levels of gambling pathology, and other psychiatric disorders, however, is incompletely understood.

Method

To use nationally representative data to examine the influence of DSM-IV nicotine dependence on the association between pathological gambling severities and other psychiatric disorders. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in 43,093 household and group-quarters adults in the United States. The main outcome measure was the co-occurrence of current nicotine dependence and Axis I and II disorders and severity of gambling based on the ten inclusionary diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling.

Results

Among non-nicotine-dependent respondents, increasing gambling severity was associated with greater psychopathology for the majority of Axis I and II disorders. This pattern was not uniformly observed among nicotine dependent subjects. Significant nicotine-by-gambling-group interactions were observed for multiple Axis I and II disorders. All significant interactions involved stronger associations between gambling and psychopathology in the non-nicotine-dependent group.

Conclusions

In a large national sample, nicotine dependence influences the associations between gambling and multiple psychiatric disorders. Subsyndromal levels of gambling are associated with significant psychopathology. Nicotine dependence accounts for some of the elevated risks for psychopathology associated with subsyndromal and problem/pathological levels of gambling. Additional research is needed to examine specific prevention and treatment for individuals with problem/pathological gambling with and without nicotine dependence.

Keywords: gambling, co-occurring disorders, nicotine dependence, addiction, impulse control disorders, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Pathological gambling is characterized by persistent and recurrent maladaptive patterns of gambling behavior that affects from 0.4-1.6% of the United States population (Shaffer et al., 1999; Petry et al., 2005). This classification typically refers to individuals who meet at least 5 of the DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling (APA, 2000). When only three or four DSM-IV criteria are met, the individual is generally referred to as a problem gambler, indicating that the gambling behavior is problematic but not as severe as pathological gambling. In studies that have used screening instruments to identify problem gamblers, problem gambling has been found in approximately 2.5% of the United States population (Shaffer and Hall, 2001).

Approximately two-thirds of the U.S. adult population report gambling in the previous year,1 and most people gamble without developing either problem or pathological gambling (PPG).2 Although pathological gambling may have a low prevalence in the community (i.e. some studies suggest it is less than 1% of population), when problem and pathological gambling (PPG) are considered together as the extreme end of a behavioral continuum of gambling, up to approximately 4% of the adult population3 report symptoms consistent with problematic gambling. Studies employing DSM-based instruments typically find lower prevalence estimates than have studies employing gambling screens cite refs 2, 18. PPG is associated with impaired functioning, reduced quality of life, and high rates of bankruptcy, divorce and incarceration.4 Increased availability and social acceptance of gambling has raised public health concerns about the potential dangers of less destructive patterns of gambling.5-6 Because of the public health implications and data suggesting that problem gambling behaviors lie along a continuum,7-9 it is important to examine the impact of varying severity levels of gambling.

Among US adults, 12.8% report nicotine dependence, and nicotine dependence is highly associated with DSM-IV Axis I and II disorders.10-13 Problem/pathological and recreational gambling are associated with elevated proportions of nicotine dependence (41% - 55% and 30%, respectively),8, 14 and tobacco smoking in clinical samples of problem and pathological gamblers has been associated with increased gambling severity and more frequent psychiatric problems.15-17 Although previous research suggests that multiple disorders are linked (gambling and psychiatric disorders,18 nicotine use and psychiatric disorders,10-13 and nicotine use and gambling),19 no study has systematically examined the interactions of gambling, nicotine, and psychiatric disorders.

We use data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a large national survey of non-institutionalized adults, to examine the relative influence of problem gambling behaviors and nicotine dependence on other psychiatric disorders. The NESARC included a DSM-IV based assessment of pathological gambling, and these data have been used previously to examine co-occurrences between pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders.18, 20 In these prior studies examining pathological gambling using the NESARC data, life-time measures of pathological gambling were employed, likely because past-year estimates of pathological gambling in the sample (approximately 0.2%) yielded less power to examine co-occurring disorders. It has been argued that lifetime prevalence estimates are less relevant to public health, “less germane to clinicians and practitioners and subject to retrospective recall bias” cite ref 10. In contrast to some prior studies that utilized lifetime measures of pathological gambling, we chose to examine past-year rates for these reasons.21-22

Prior studies have found elevated odds of co-occurrence between subsyndromal levels of gambling and non-gambling psychopathology. For example, in the St. Louis site of the ECA survey, recreational gambling was associated with a broad range of mainly Axis I disorders. Although informative, the gambling data from the ECA study were geographically limited to the St. Louis site, utilized earlier iterations of DSM criteria, and did not assess for a broad range of Axis II disorders. Given the incomplete data on the co-occurrence of different levels of gambling, nicotine use, and a broad range of psychiatric disorders,18 the purpose of this study was to fill these gaps in knowledge. Specifically, using the NESARC data we sought to: 1) Examine the prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of varying levels of gambling pathology in nicotine dependent and non-nicotine dependent individuals; 2) Compare prevalence estimates of psychiatric disorders in nicotine and non-nicotine dependent individuals based on level of gambling pathology; and 3) Investigate the influences of nicotine dependence and gambling pathology and their interaction on a range of psychiatric disorders. Recognizing the associations between gambling severity, nicotine status and psychiatric disorders is important, as identifying and treating the co-occurring disorders may significantly improve the prognosis of the primary disorder. Additionally, to the extent that co-occurring disorders may potentially contribute to the development or maintenance of PPG, it is also important to recognize the possible associations with PPG, which is often under-recognized in clinical settings.

METHOD

Sample

Data from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), described elsewhere,10, 23 were analyzed. Briefly, the NESARC, conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and the Bureau of the Census, surveyed a nationally representative sample of non-institutionalized U.S. residents (citizens and non-citizens) aged 18 years and over. Respondents were identified using a multi-stage stratified sample, and the sample was enhanced with members of group-living environments, such as dormitories, group homes, shelters, and facilities for housing workers. Jails, prisons, and hospitals were not included. The study over-sampled black and Hispanic households, as well as young adults aged 18 to 24 years, in order to have sufficient power to perform meaningful analyses focusing on these populations. Weights have been calculated to adjust standard errors for these over-samples and non-response.23 The final sample consisted of 43,093 respondents, representing an 81% response rate. After complete description of the study to the subjects, informed consent was obtained. The current investigation utilized publicly accessible, de-identified data and was thus exempted from formal institutional review board review.

Measures

The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM IV version (AUDADIS-IV),24 a structured diagnostic assessment tool, was administered by trained lay interviewers in the NESARC study. The AUDADIS-IV has demonstrated good reliability and validity for detecting psychiatric disorders in a community sample.24 The NESARC data set contains diagnostic variables derived from AUDADIS-IV algorithms and based on DSM-IV criteria. The data contain diagnostic variables for major depression, dysthymia, mania and hypomania, panic disorder with and without agoraphobia, social phobia, simple phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse and dependence, drug abuse and dependence, and nicotine dependence. We used past-year measures of these disorders. Lifetime measures were used of the seven DSM-IV Axis II disorders assessed with the AUDADIS-IV: antisocial, avoidant, dependent, histrionic, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, and schizoid personality disorders.

The primary independent variable in the present analyses was severity of problem gambling, based on the ten DSM-IV diagnostic inclusionary criteria for pathological gambling. Consistent with previous population-based studies including those using the NESARC data,5, 22, 25-26 we divided the sample into four groups: non-gamblers and low-frequency gamblers were those who reported that they had never gambled >5 times in a single year in their lifetime (referred to hereafter as “non-low-frequency gamblers”); low-risk gamblers were those who reported gambling >5 times in a year and no symptoms of pathological gambling in the previous year; at-risk gamblers were those who reported gambling >5 times in a year and 1-2 symptoms of pathological gambling in the previous year; and problem/pathological gamblers (PPG) were those who reported ≥3 DSM-IV criteria of pathological gambling in the previous year. The low frequency of pathological gambling (approximately 0.2% of the sample reported ≥5 symptoms) necessitated the combination of the problem and pathological groups, a strategy employed in prior gambling studies.8, 22, 26

The following socio-demographic variables were included in analyses: age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and employment status. Dummy variables for three race/ethnicity groups were created (black, white, and Hispanic). These groups were not mutually exclusive as a respondent could have identified with more than one race or ethnicity. As previously (cite ref 22), we employed the approach of using non-mutually exclusive categories, consistent with current federal guidelines as described by the Office of Management and Budget (cite http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=10887&page=212).

Data Analyses

The primary research question concerned differences in the associations between gambling and psychiatric disorders based on DSM-IV past-year nicotine dependence (nicotine-dependent vs. non-nicotine-dependent). Using chi-square analyses, we first examined associations between gambling severity and socio-demographic variables, stratified by nicotine dependence, in order to identify socio-demographic variables potentially influencing the relationship between nicotine dependence, gambling severity and psychiatric disorders. Next, we examined unadjusted weighted rates of psychiatric disorders, stratified by both gambling severity and nicotine dependence. Finally, we fit a series of logistic regression models where psychiatric disorders were the dependent variables of interest and the four-level gambling variable, nicotine dependence, and an interaction between nicotine dependence and gambling were the independent variables of interest, adjusting for previously identified socio-demographic variables. Our analysis began with examining psychiatric disorders grouped into four categories: any mood disorder, any anxiety disorder, any substance use disorder, and any personality disorder. Only when a significant association was found between these categories and gambling severity and nicotine status did we pursue an analysis of the individual disorders. Because only four comparisons were initially made, and these were significant, we did not adjust our alpha level to account for the multiple subsequent comparisons. Analyses were performed using SUDAAN software27 and the NESARC-calculated weights in order to adjust the data for the design effects of the NESARC.

RESULTS

Rates of Gambling Pathology Based on Nicotine Status

Of the 43,093 respondents, 4,962 (12.8%) were nicotine dependent.10 Compared with non-nicotine dependent respondents, the nicotine-dependent group was significantly more likely to be male, white, working part-time or full-time, and previously or never married (Table 1). Of the 43,093 respondents, 30,885 (71.7%) were non-gamblers, 9,964 (23.1%) were low-risk gamblers, 945 (2.2%) were at-risk gamblers, and 233 (0.5%) were PPG. Percentages of subjects with low-risk, at-risk and PPG gambling severity were higher among nicotine dependent respondents. Among respondents who were nicotine dependent (n=4,962), prevalence estimates for non-gambling, low-risk gambling, at-risk gambling, and PPG were 59.7%, 31.6%, 4.9% and 1.9%, respectively, compared to estimates of 73.2%, 22.0%, 1.8% and 0.4%, respectively, in the non-nicotine-dependent group (n=38,131).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the NESARC sample by nicotine dependence

| Nicotine Dependent (n=4,962) |

Non-nicotine Dependent (n=38,131) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | % | N | % | χ 2 | p |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 2572 | 46.87 | 22003 | 52.84 | 34.53 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 2390 | 53.13 | 16128 | 47.16 | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 978 | 18.61 | 6871 | 15.22 | 127.12 | <0.0001 |

| High school graduate | 1689 | 35.15 | 10858 | 28.47 | ||

| Some college | 1709 | 34.63 | 10954 | 29.48 | ||

| College or higher | 586 | 11.6 | 9448 | 26.83 | ||

| Employment | ||||||

| Full time | 2697 | 56.52 | 19570 | 53.04 | 20.73 | 0.0001 |

| Part time | 530 | 11.17 | 3733 | 10.39 | ||

| Not working | 1735 | 32.31 | 14828 | 36.57 | ||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 2134 | 53.63 | 19947 | 62.79 | 66.15 | <0.0001 |

| Previously married | 1454 | 21.52 | 9663 | 16.86 | ||

| Never married | 1374 | 24.84 | 8521 | 20.34 | ||

| White race | 3952 | 87.3 | 28837 | 82.65 | 38.28 | <0.0001 |

| Black race | 872 | 9.36 | 7728 | 11.9 | 21.96 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 536 | 5.69 | 7772 | 12.42 | 28.54 | <0.0001 |

Ns represent actual number of respondents in each category; % indicate weighted percentages

Sociodemographic Variables Based on Gambling Pathology and Nicotine Dependence Status

Table 2 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of the groups divided on nicotine dependence status and stratified by level of gambling pathology. Among nicotine dependent respondents, significant associations with gambling status at p<0.05 were observed related to gender, education, and marital status. Among non-nicotine-dependent respondents, significant associations with gambling status were observed on all socio-demographic measures. Some gambling-related differences appear similar in both nicotine dependent and non-dependent groups. For example, higher proportions of men and Blacks were observed in the at-risk and PPG gamblers regardless of nicotine dependence. Other gambling-related differences appeared different in the two nicotine-related groups. For example, the relatively lower proportions of married individuals in the at-risk gambling and PPG groups in the non-nicotine-dependent group were not evident in the nicotine dependent group.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of sample by nicotine dependence and level of gambling pathology

| Nicotine Dependent2-3 | Non-nicotine Dependent2-3 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Characteristic | Non/LF- gamblers4 (n=2,961) |

Low-risk gamblers (n=1,568) |

At-risk gamblers (n=244) |

Problem/ pathological gamblers (n=96) |

χ 2 | p | Non/LF- gamblers4 (n=27,924) |

Low-risk gamblers (n=8,396) |

At-risk gamblers (n=701) |

Problem/ pathological gamblers (n=137) |

χ 2 | p |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 52.55 | 38.75 | 41.85 | 34.39 | 45.83 | <0.0001 | 56.82 | 42.57 | 35.05 | 35.75 | 109.44 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 47.45 | 61.25 | 58.15 | 65.61 | 43.18 | 57.43 | 64.95 | 64.25 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than high School |

18.46 | 17.98 | 22.39 | 23.46 | 21.76 | 0.0196 | 16.1 | 12.06 | 13.8 | 16.38 | 57 | <0.0001 |

| High school Graduate |

35.37 | 33.72 | 37.44 | 51.25 | 27.81 | 30.17 | 30.63 | 26.84 | ||||

| Some college | 34.11 | 36.37 | 32.30 | 19.67 | 28.76 | 31.71 | 33.23 | 33.99 | ||||

| College or Higher |

12.06 | 11.92 | 7.87 | 5.62 | 27.34 | 26.07 | 22.33 | 22.79 | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||||||

| Full time | 55.28 | 57.63 | 61.32 | 57.89 | 3.92 | 0.6866 | 51.88 | 56.21 | 27.14 | 54.1 | 29.06 | 0.0004 |

| Part time | 11.65 | 10.94 | 10.69 | 8.24 | 10.73 | 9.3 | 9.37 | 15.8 | ||||

| Not working | 33.07 | 31.44 | 27.99 | 33.87 | 37.39 | 34.49 | 33.49 | 30.1 | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| Married | 51.72 | 57.43 | 56.16 | 55.31 | 21.35 | 0.0042 | 62.18 | 66.99 | 55.63 | 40.83 | 73.03 | <0.0001 |

| Previously Married |

21.26 | 22.32 | 17.61 | 16.76 | 16.55 | 17.18 | 18.01 | 21.86 | ||||

| Never married | 27.02 | 20.26 | 26.23 | 27.93 | 21.27 | 15.83 | 26.36 | 37.31 | ||||

| White race1 | 87.78 | 87.82 | 83.57 | 76.99 | 7.95 | 0.0561 | 82.19 | 84.54 | 81.71 | 59.49 | 31.75 | <0.0001 |

| Black race | 9.36 | 8.13 | 12.85 | 14.52 | 8.18 | 0.0512 | 11.93 | 11.27 | 14.03 | 27.65 | 17.55 | 0.0013 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 6.24 | 4.71 | 5.62 | 3.28 | 6.73 | 0.0916 | 13.7 | 8.76 | 8.85 | 9.33 | 29.01 | <0.0001 |

Race and ethnicity categories are not mutually exclusive

Numbers in table represent weighted percentages, stratified by gender

There were 93 nicotine-dependent and 973 non-nicotine-dependent respondents with missing data on gambling

Non/LF=non or low-frequency gamblers

Psychiatric Disorders, Nicotine Dependence Status, and Level of Gambling Pathology

Differences in the associations between gambling severity and psychopathology were observed in the groups stratified by nicotine dependence status (Table 3). Within both the nicotine-dependent and non-nicotine-dependent groups and as compared to non-gambling and low-risk gambling groups, estimates of co-occurring psychopathology were higher in the at-risk gambling group and higher still in the PPG group. In virtually all instances, nicotine-dependent respondents had numerically higher estimates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders at each gambling severity level.

Table 3.

Rates of psychiatric diagnoses by level of gambling pathology and nicotine dependence

| Nicotine Dependent |

Non-nicotine Dependent |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Non/LF- gamblers 4 |

Low-risk gamblers |

At-risk gamblers |

Problem/ pathological gamblers |

χ 2 | p | Non/LF- gamblers 3 |

Low-risk gamblers |

At-risk gamblers |

Problem/ pathological gamblers |

χ 2 | p |

| Any Mood Disorder | 22.35 | 18.60 | 25.24 | 23.65 | 2.56 | 0.0628 | 7.44 | 7.32 | 14.10 | 25.23 | 12.64 | <0.0001 |

| Major Depression | 18.46 | 13.93 | 16.71 | 14.77 | 9.7 | 0.0279 | 5.81 | 5.23 | 8.88 | 16.11 | 17.2 | 0.0015 |

| Dysthymia | 4.91 | 3.99 | 5.08 | 4.46 | 1.68 | 0.6429 | 1.41 | 1.38 | 2.18 | 6.85 | 6.15 | 0.1154 |

| Mania | 4.69 | 4.50 | 2.76 | 10.43 | 4.47 | 0.2253 | 1.09 | 1.49 | 3.65 | 7.03 | 19 | 0.0008 |

| Hypomania | 3.04 | 2.86 | 6.07 | 0.27 | 21.78 | 0.0003 | 0.8 | 0.97 | 3.04 | 4.23 | 11.4 | 0.0144 |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 22.56 | 20.68 | 24.91 | 38.66 | 3.04 | 0.0353 | 8.99 | 11.24 | 16.90 | 23.09 | 13.34 | <0.0001 |

| Panic Disorder1 | 6.53 | 4.7 | 9.87 | 11.37 | 8.47 | 0.0455 | 1.46 | 1.63 | 4.44 | 3.85 | 8.46 | 0.0458 |

| Social phobia | 6.12 | 5.29 | 6.83 | 8.73 | 1.95 | 0.5853 | 2.21 | 2.62 | 3.62 | 10.26 | 8.72 | 0.0411 |

| Simple phobia | 14.01 | 14 | 18.82 | 28.33 | 7.59 | 0.065 | 5.74 | 7.28 | 10.55 | 15.96 | 28.2 | <0.0001 |

| Generalized anxiety | 5.38 | 5.26 | 3.54 | 11.65 | 2.82 | 0.2912 | 1.54 | 1.79 | 2.62 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 0.1901 |

| Any AUD or SUD 2 | 23.53 | 26.39 | 39.69 | 45.11 | 7.71 | 0.0002 | 5.66 | 9.71 | 17.91 | 24.29 | 28.90 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol ab/dep 3 | 20.76 | 22.91 | 38.27 | 42.52 | 24.93 | 0.0001 | 5.08 | 9.21 | 16.24 | 21.48 | 82.1 | <0.0001 |

| Drug ab/dep | 7.32 | 8.92 | 13.4 | 7.47 | 5.09 | 0.1767 | 0.97 | 1.28 | 3.47 | 4.71 | 16.3 | 0.0021 |

| Any Axis II Disorder | 31.34 | 30.76 | 40.73 | 60.95 | 8.14 | 0.0001 | 11.19 | 15.43 | 27.03 | 48.63 | 28.26 | <0.0001 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Avoidant | 6.47 | 4.16 | 8.59 | 10.49 | 11.67 | 0.0128 | 1.92 | 1.63 | 3.12 | 9.02 | 8.19 | 0.0509 |

| Dependent | 1.7 | 1.76 | 1.03 | 3.77 | 2.10 | 0.5557 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.4 | 2.17 | 13.9 | 0.0053 |

| Antisocial | 10.93 | 13.29 | 18.15 | 25.79 | 13.6 | 0.006 | 1.87 | 3.58 | 7.21 | 16.74 | 50.4 | <0.0001 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 14.42 | 13.44 | 20.16 | 25.82 | 9.99 | 0.0249 | 6.3 | 8.78 | 14.39 | 23.64 | 52.3 | <0.0001 |

| Paranoid | 12.26 | 9.98 | 14.77 | 28.6 | 13.38 | 0.0065 | 3.09 | 3.73 | 8.19 | 23.79 | 30.8 | <0.0001 |

| Schizoid | 7.77 | 7.1 | 9.1 | 17.64 | 5.04 | 0.1799 | 2.28 | 2.93 | 4.63 | 14.32 | 21.6 | 0.0003 |

| Histrionic | 5.76 | 4.31 | 8.12 | 18.86 | 11.22 | 0.0153 | 1.17 | 1.47 | 4.38 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 0.0153 |

With or without agoraphobia

AUD=alcohol use disorder; SUD=-substance use disorder

ab/dep=abuse or dependence

Non/LF=non or low-frequency gamblers

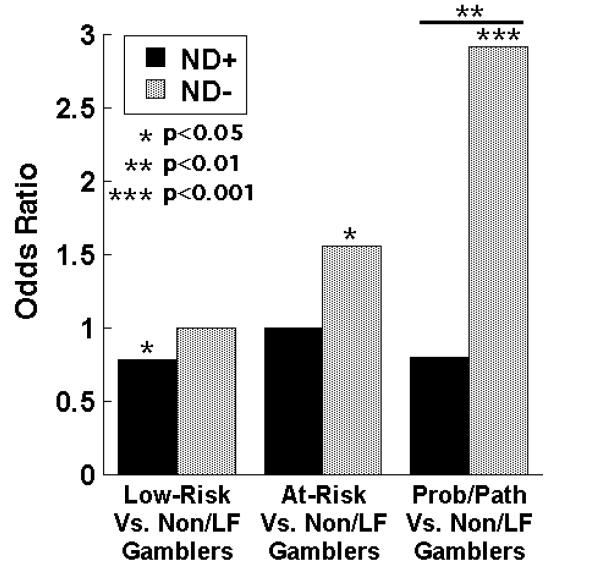

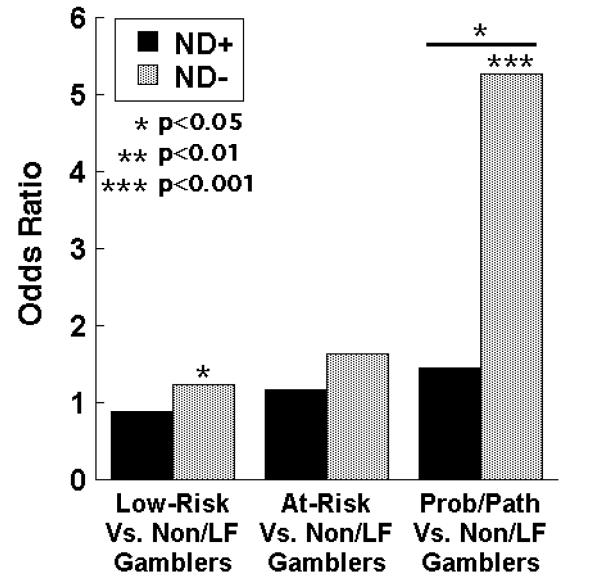

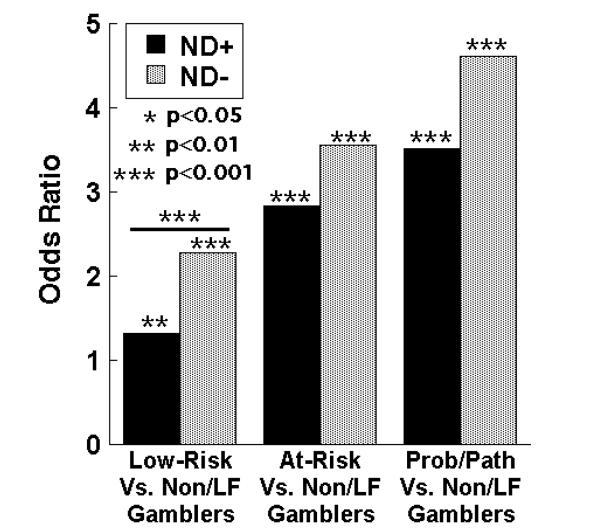

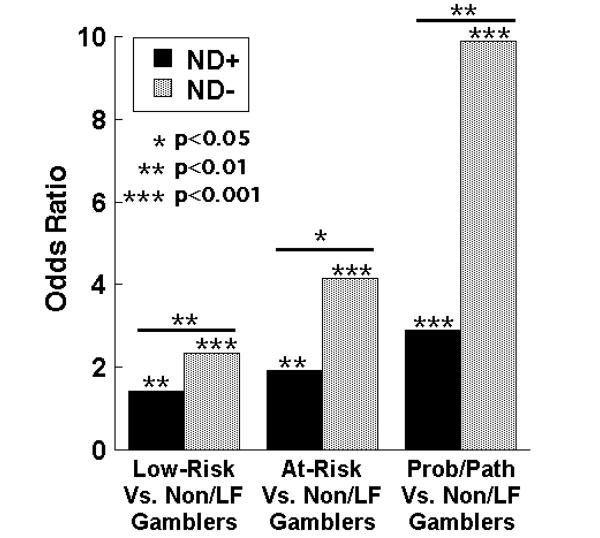

Logistic regression models examined the influences of nicotine dependence, gambling severity and their interaction upon the odds ratios for other psychiatric disorders (Table 4). Significant gambling-by-nicotine-group interactions were observed for mood, anxiety, substance use and personality disorders (Figure 1). Subsequent analyses identified significant interactions for the following Axis I conditions: major depression, mania, hypomania, social phobia, simple phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol abuse/dependence, and drug abuse/dependence. Significant gambling-by-nicotine-group interactions were also observed for most Axis II disorders: antisocial, obsessive compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, and histrionic. In all cases in which a significant interaction was observed, a stronger association between gambling severity and psychopathology was observed in the non-nicotine-dependent group as compared to the nicotine-dependent one.

Table 4.

Adjusted associations between gambling and psychiatric diagnoses, by nicotine dependence

| Nicotine Dependent |

Non-nicotine dependent |

ND vs NND interaction |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | OR for Low- risk vs. Non/LF- gamblers 1,2 |

OR for At- Risk vs Non/LF- gamblers |

OR for prob/path vs Non/LF- gamblers |

OR for Low- risk vs. Non/LF- gamblers |

OR for At- Risk vs Non/LF- gamblers |

OR for prob/path vs Non/LF- gamblers |

Low-risk gamblers |

At-risk gamblers |

Prob/ path gamblers |

|

|

|

||||||||

| Any Mood Disorder | 0.87 | 1.33 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 2.04† | 3.92† | 0.78* | 0.65* | 0.29** |

| Major Depression | 0.78* | 1 | 0.8 | 1.09 | 1.8† | 3.43† | 0.78 | 0.6* | 0.26** |

| Dysthymia | 0.86 | 1.17 | 0.87 | 1.15 | 1.74* | 5.83† | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.16* |

| Mania | 1.13 | 0.65 | 2.48 | 1.71† | 3.65† | 6.42† | 0.68 | 0.18† | 0.4 |

| Hypomania | 1.12 | 2.24* | 0.09* | 1.52* | 3.81† | 4.39* | 0.75 | 0.6 | 0.02** |

| Panic Disorder | 0.75 | 1.8* | 2.01 | 1.36* | 3.91† | 3.42* | 0.61* | 0.49 | 0.68 |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 0.92 | 1.21 | 2.27** | 1.34† | 2.07† | 3.04† | 0.69† | 0.59* | 0.75 |

| Social phobia | 0.89 | 1.17 | 1.45 | 1.33** | 1.83* | 5.97† | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.27* |

| Simple phobia | 1.03 | 1.5 | 2.54** | 1.51† | 2.36† | 3.8† | 0.77* | 0.69 | 0.79 |

| Generalized anxiety | 1.03 | 0.71 | 2.41 | 1.39** | 2.04** | 3.6* | 0.82 | 0.38* | 0.77 |

| Any AUD or SUD | 1.37† | 2.55† | 3.26† | 2.18† | 3.61† | 4.87† | 0.63† | 0.71 | 0.67 |

| Alcohol ab/dep | 1.32 | 2.83 | 3.51 | 2.06† | 3.04† | 3.88† | 0.57† | 0.87 | 0.83 |

| Drug ab/dep | 1.64 | 2.3 | 1.00 | 1.64** | 3.12† | 3.33** | 0.9 | 0.66 | 0.27* |

| Any Axis II Disorder | 1.04 | 1.59** | 3.60† | 1.57† | 2.96† | 7.10† | 0.66† | 0.54** | 0.51* |

|

| |||||||||

| Avoidant | 0.7* | 1.49 | 1.65 | 1.01 | 1.77 | 5.34† | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.33 |

| Dependent | 1.24 | 0.72 | 2.1 | 0.56 | 1.21 | 7.16† | 2.31 | 0.62 | 0.31 |

| Antisocial | 1.42† | 1.93† | 2.89† | 2.05† | 3.46† | 8.25† | 0.61** | 0.5* | 0.31** |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 0.93 | 1.56* | 2.21** | 1.46** | 2.54† | 4.65† | 0.64† | 0.62* | 0.48* |

| Paranoid | 0.89 | 1.3 | 2.88† | 1.5† | 2.99† | 9.26† | 0.62 | 0.45** | 0.33* |

| Schizoid | 0.98 | 1.22 | 2.53** | 1.42† | 2.09† | 6.35† | 0.69* | 0.58 | 0.4 |

| Histrionic | 0.85 | 1.59 | 3.99† | 1.51** | 3.79† | 6.93† | 0.57* | 0.42* | 0.58 |

Odds ratios (OR) are adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment, and income

Non/LF=non or low-frequency gamblers

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Figure 1.

a. Interactions with nicotine dependence in the associations between major depression and gambling severity

b. Interactions with nicotine dependence in the associations between social phobia and gambling severity

c. Interactions with nicotine dependence in the associations between alcohol abuse/dependence and gambling severity

d. Interactions with nicotine dependence in the associations between antisocial personality disorder and gambling severity

The patterns of associations between gambling severity and psychopathology appeared substantially influenced by nicotine dependence. Differences were observed at the severe end of the gambling spectrum for many disorders. In the PPG vs. non-gambling comparisons, the non-nicotine dependent group demonstrated significant odds ratio of >3.3 for every Axis I and II disorder. In contrast, only one Axis I disorder (alcohol abuse/dependence) and one Axis II disorder (histrionic personality disorder) demonstrated an odds ratio ≥ 3 in comparisons within the nicotine dependent group.

A pattern of a step-wise progression for increasingly larger odds ratios was observed for increasing gambling severity in the at-risk and PPG groups for virtually all Axis I and II psychiatric disorders in the non-nicotine-dependent group. This pattern was less consistently observed in the nicotine-dependent group. Unique features were observed for each disorder in the patterns of associations in the nicotine dependent and non-dependent groups. For example, gambling severity did not confer additional risk for major depression in the nicotine dependent group (Table 4), with significant between-nicotine-group differences observed only for the PPG comparison. Within the nicotine-dependent group, the most statistically significant association with major depression was a decreased odds in the low-risk vs. non-gambling comparison (OR=0.78; p<0.05). Similarly, social phobia demonstrated a significant interaction effect for the PPG versus non-gambling comparison; however, no significant association was observed between social phobia and problem gambling severity within the nicotine dependent group. Largely similar step-wise progressions were observed between problem gambling severity and alcohol abuse/dependence in nicotine-dependent and non-dependent groups, with a significant between-group difference observed only in the low-risk versus non-gambling comparison. With antisocial personality disorder, significant positive associations were observed across all gambling severity groups in both the nicotine-dependent and non-dependent groups, with significantly stronger associations observed in the non-nicotine dependent group comparisons.

DISCUSSION

This study is to our knowledge the first to examine the association between nicotine dependence, problem gambling severity, and a broad range of Axis I and II psychiatric disorders in a nationally representative sample. The multiple strengths of the survey, including the high response rate, large population-based sample, and diagnostic measures obtained, allow for examination of the interactive influences of psychiatric disorders. This study found that more severe problem gambling is associated with more psychopathology in both nicotine dependent and non-nicotine dependent respondents, and this pattern applies to a broad range of Axis I and II disorders. Previous studies found that PPG is associated with an increased risk for multiple psychiatric disorders.4, 7-8 Consistent with these previous studies, this study found that individuals with PPG had elevated rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

In the non-nicotine dependent group, the association between gambling severity and psychopathology was seen for the majority of Axis I and II disorders and was particularly robust for major depression and antisocial personality disorders. The finding that the nicotine dependent group had higher prevalence estimates of psychiatric disorders, and yet psychopathology generally had a weaker association with gambling in the nicotine dependent group, suggests that some of the gambling-related risk for these disorders is attributable to nicotine dependence.

Tobacco use may co-occur with gambling for multiple reasons. Biological (e.g., genetic factors) such as those contributing to impulsivity or related constructs may contribute to participation in both behaviors cite MJ Kreek et al Nat Neurosci Rev 2005 ms on impulsivity genetics and addiction. Preclinical data suggest that nicotine use may enhance dopamine response to reinforcers by facilitating burst firing of dopamine neurons (Rice & Cragg, 2004; Zhang & Sulzer, 2004). The ventral striatum, a dopaminergically innervated brain region, has been identified in some studies of pathological gambling cite Reuter et al 2005, although a role for striatal dopamine involvement in pathological gambling has yet to be empirically demonstrated. Gambling and smoking may be related to common social or environmental factors, such as gambling and smoking together among friends or in casinos. Specific influences of tobacco smoking (calming, stimulating, attention-related, coping with stress) may enhance gambling experiences. The extent to which the relationship between gambling and smoking is mediated by specific environmental, genetic or other biological factors warrants further examination.

Examination of the relationships between smoking, gambling, and other psychiatric disorders may provide insight into how these disorders fit in the structure of psychiatric conditions. Data indicate that common psychiatric disorders aggregate in two main groups: internalizing and externalizing disorders (i.e. disorders characterized by either withdrawal from society or in conflict with society, respectively).28-29 Where PPG fits within this structure is not completely understood, particularly as assessments of gambling problems have often been omitted from major psychiatric epidemiological studies.30 PPG shares with externalizing disorders (for example, substance use disorders and antisocial personality disorder) a disinhibited personality style and lack of constraint.29 PPG also shares with internalizing disorders (for example, major depressive disorder and social phobia) an uncomfortable mood or anxiety state that often precedes gambling. Existing data suggest strong genetic contributions between pathological gambling and internalizing31 and externalizing9, 32 disorders, respectively. Further study, particularly using DSM-based measures of pathological gambling in conjunction with DSM-based measures of other psychiatric disorders, may provide important insight into how best to categorize pathological gambling.

The relationship between nicotine dependence and externalizing/internalizing disorders is also unsettled, with findings arguably suggesting a stronger clustering with externalizing disorders. Associations between daily cigarette smoking and most psychiatric disorders have been demonstrated in multiple studies.33-34 Although nicotine dependence has also been associated with internalizing disorders like major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders,13, 35-36 strong associations between daily tobacco smoking or nicotine dependence have been found for substance use disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and antisocial personality disorder.13, 33, 35, 37 A strong association exists between progression to daily smoking and externalizing disorders with externalizing disorders predicting the development of nicotine dependence from daily smoking.33

In this study, the nicotine dependent group demonstrated high estimates of major depression regardless of gambling severity. In other words, more severe gambling behaviors did not increase the risk for depression among nicotine dependent subjects, suggesting an overlap in the factors contributing to nicotine dependence and problem gambling behaviors as they relate to depression. In that low-risk gamblers had a low odds ratio for major depression compared to non-gamblers among nicotine dependent subjects, it suggests that low-level gambling behaviors either have a mood-protecting influence in smokers or that a depressed mood amongst smokers interferes with participation in low-risk gambling. Previous studies have suggested that neuroticism may be a common predisposition to both nicotine dependence and major depression13 and that smoking may assist in managing mood symptoms.10 Further research is needed to examine the extent to which these or other factors mediate the relationship between tobacco smoking, depression and gambling.

Although more severe gambling behaviors increased the risk for all anxiety disorders in both nicotine dependent and non-dependent groups, the association between gambling and anxiety disorders was substantially stronger in the non-dependent group. Research indicates that nicotine use has anxiolytic properties.38-39 The greater odds ratio for anxiety disorders within the non-dependent group suggest that gambling severity level may be indicative of the anxiolytic properties of gambling behaviors and implicate a neurobiological pathway common to gambling and tobacco use. Given the high rates of anxiety disorders in individuals with disordered gambling,4 these findings may have treatment implications for preventing gambling relapse in PPG groups.

Clinical Implications.

The data yield several important conclusions. First, PPG in non-nicotine dependent adults was associated with a broad range of psychopathology. Second, even low-risk gambling in non-nicotine dependent respondents was positively associated with multiple psychiatric disorders, including drug and alcohol use disorders, anxiety, and mania. Given the increased popularity of gambling as a recreational activity, there has been significant concern about the potential public health threat posed by subsyndromal levels of gambling.3 To date, there has been relatively little research exploring low-risk gambling patterns and correlates,5 and existing studies have frequently not used diagnostic measures of psychopathology.5,40 Consistent with these studies,5,40 the current findings indicate that even low-risk gambling is associated with significant psychopathology in certain groups; e.g., non-nicotine-dependent subjects. Although there are no diagnostic criteria for levels of gambling pathology except pathological gambling, this finding suggests that gambling may be more accurately seen as a spectrum of disease cite refs7-9. Regardless of the underlying mechanism for the association, these results raise concern that low-risk gambling in non-smoking individuals may be more reflective of psychopathology than is such gambling in nicotine dependent groups. This has implications for: 1) primary care, where screening and brief interventions around gambling, smoking and other psychiatric disorders could be implemented; and, 2) public policy related to the expansion in availability of gambling venues.

Our study is the first to find that nicotine dependence influences the association between gambling severity and psychopathology. The study’s strengths are its survey design, large nationally representative sample, the inclusion of a wide range of DSM-IV Axis I and II disorders, and the response rate (81%). Despite these strengths, this study has several important limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data precludes our ability to establish temporal patterns between problem gambling behavior, psychopathology and nicotine dependence. It is therefore possible to suggest several competing, though not necessarily mutually exclusive, explanations, all of which are consistent with the data. Second, low rates of pathological gambling were reported, necessitating combining problem and pathological gambling into a single category. It is possible that there exist significant differences in psychopathology between problem and pathological gambling. Third, although pathological gambling in this study was based on DSM-IV criteria, the exclusionary criterion of DSM-IV (i.e. diagnosis of athological gambling is not given if it occurs during a manic episode) was not assessed. Therefore, pathological gambling is this study may differ from DSM-IV pathological gambling. Fourth, there are no established standards for categorizing gambling behavior across a continuum. Although these groupings have been used in previous studies,5, 21, 25 they are not based on empirically-derived thresholds.

This study highlights the need for future research. In particular, research focusing on a possible biological basis for the associations between gambling, nicotine dependence, and other psychopathology is needed. Additionally, given the clinical and public health concerns of these associations, future research should address both primary and secondary interventions.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by: (1) the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA019039); (2) the National Institute on Mental Health (K23 MH069754-01A1); (3) the Veterans Administration VISN1 MIRECC and REAP; and (4) Women’s Health Research at Yale.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Grant has received research grants from Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Somaxon Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Grant has also been a consultant to Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and Somaxon Pharmaceuticals and has consulted for law offices as an expert in pathological gambling.

Dr. Desai reports no financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

Dr. Potenza consults for and is an advisor to Boehringer Ingelheim, receives research support from Mohegan Sun, has consulted for and has financial interests in Somaxon, and has consulted for law offices and the federal defender’s office as an expert in pathological gambling and impulse control disorders.

Contributor Information

Jon E. Grant, Department of Psychiatry University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN.

Rani A. Desai, Department of Psychiatry Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Marc N. Potenza, Department of Psychiatry Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

REFERENCES

- 1.Potenza MN, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Pathological gambling. JAMA. 2001;286:141–144. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaffer HJ, Hall MN. Updating and refining prevalence estimates of disordered gambling behaviour in the United States and Canada. Can J Public Health. 2001;92:168–172. doi: 10.1007/BF03404298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: a research synthesis. Am J Pub Health. 1999;89:1369–1376. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argo T, Black DW. Clinical characteristics. In: Grant JE, Potenza MN, editors. Pathological Gambling: A Clinical Guide to Treatment. American Psychiatric Publishingp; Washington, DC: 2004. pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai RA, Maciejewski PK, Dausey DJ, Caldarone BJ, Potenza MN. Health correlates of recreational gambling in older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1672–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaffer HJ, Korn DA. Gambling and related mental disorders: a public health analysis. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:171–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crockford DN, El-Guebaly N. Psychiatric comorbidity in pathological gambling: a critical review. Can J Psychiatry. 1998;43:43–50. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB, Compton WM, III, et al. Taking chances: Problem gamblers and mental health disorders – results from the St. Louis Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1093–1096. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.7.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slutske WS, Eisen S, True WR, et al. Common genetic vulnerability for pathological gambling and alcohol dependence in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:666–673. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslau N. Psychiatric comorbidity of smoking and nicotine dependence. Behav Genet. 1995;25:95–101. doi: 10.1007/BF02196920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. DSM-III-R nicotine dependence in young adults: prevalence, correlates and associated psychiatric disorders. Addiction. 1994;89:743–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence, major depression, and anxiety in young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1069–1074. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smart RG, Ferris J. Alcohol, drugs and gambling in the Ontario adult population, 1994. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41:36–45. doi: 10.1177/070674379604100109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petry NM, Oncken C. Cigarette smoking is associated with increased severity of gambling problems in treatment-seeking gamblers. Addiction. 2002;97:745–753. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant JE, Potenza MN. Tobacco use and pathological gambling. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17:237–241. doi: 10.1080/10401230500295370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potenza MN, Steinberg MA, McLaughlin SD, et al. Characteristics of tobacco-smoking problem gamblers calling a gambling helpline. Am J Addict. 2004;13:471–493. doi: 10.1080/10550490490483044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morasco BJ, Pietrzak RH, Blanco C, et al. Health problems and medical utilization associated with gambling disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(6):976–984. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000238466.76172.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanco C, Hasin DS, Petry N, et al. Sex differences in subclinical and DSM-IV pathological gambling: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:943–953. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, et al. Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1226–1233. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.12.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desai RA, Desai MM, Potenza MN. Gambling, health, and age: Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychology Addict Behav. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.431. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant BF, Moore TC, Shepard J, et al. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Bethesda, MD: [Accessed July 6, 2006]. 2003. Available at: www.niaaa.nih.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Opinion Research Center . Gambling Impact and Behavior Study. University of Chicago; Chicago, IL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desai RA, Maciejewski PK, Pantalon MV, et al. Gender differences among recreational gamblers: association with the frequency of alcohol use. Psychology Addict Behav. 2006;20:145–153. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Research Triangle Institute . Software for Survey Data Analysis (SUDAAN) Version 8.1 Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Potenza MN. Impulse control disorders and co-occurring disorders: dual diagnosis considerations. J Dual Diagnosis. 2007;3(2):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, et al. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: modeling the externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potenza MN, Xian H, Shah K, et al. Shared genetic contributions to pathological gambling and major depression in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1015–1021. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slutske WS, Eisen S, Xian H, et al. A twin study of the association between pathological gambling and antisocial personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:297–308. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rohde P, Kahler CW, Lewinsohn PM, et al. Psychiatric disorders, familial factors, and cigarette smoking: II. Associations with progression to daily smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:119–132. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Wollhandler S, et al. Smoking and mental illness. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Sullivan P, et al. A population-based twin study in women of smoking initiation and nicotine dependence. Psychol Med. 1999;29:299–308. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, et al. Major depression and stages of smoking: a longitudinal investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:161–166. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown RA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, et al. Cigarette smoking, major depression and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 1996;35:1602–1610. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199612000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Booker TK, Butt CM, Wehner JM, et al. Decreased anxiety-like behavior in beta3 nicotinic receptor subunit knockout mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buckley TC, Holohan DR, Mozley SL, et al. The effect of nicotine and attention allocation on physiological and self-report measures of induced anxiety in PTSD: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:154–164. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch WJ, Maciejewski PK, Potenza MN. Psychiatric correlates of gambling in adolescents and young adults grouped by age at gambling onset. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1116–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]