Abstract

Purpose

To empirically derive latent classes based on PG criteria and to assess the association between non-gambling psychiatric disorders and specific classes.

Methods

8,138 community-based middle-aged men were surveyed and 2,720 were assessed for DSM-III-R pathological gambling (PG). Latent class analysis (LCA) was applied to DSM-III-R PG criteria to identify gambling classes. Chi-square and logistic regression models evaluated the association between gambling classes and lifetime psychiatric disorders.

Results

The final model included four classes: class 0 (i.e., 5,418 individuals who never gambled 25 or more times in a year) and classes 1–3 (identified by the LCA and comprising 2,720 respondents assessed for PG). For the nine individual criteria of PG, endorsement percentages ranged from 2% - 6%, 4% - 58%, and 53% −100% for classes 1–3, respectively. Non-gambling psychiatric disorders were differentially associated with the four gambling classes, and psychopathology was more common in groups more frequently acknowledging PG criteria.

Conclusions

Empirical support is provided for distinct classes of gambling behaviors demonstrating differential associations with individual PG criteria and non-gambling psychiatric disorders. The data-driven categorization of gambling behaviors provides direction for research on defining, preventing and treating syndromal and subsyndromal PG.

Keywords: Pathological Gambling (PG), Latent Class, PG Criteria

Introduction

Pathological gambling (PG) is formally classified as an impulse control disorder1 and has been associated with high rates of divorce, bankruptcy, unemployment and suicidality.2,3 PG is relatively common with lifetime and past-year prevalence estimates of 3.5% and 1.3%, respectively, recently observed in a United States community sample.4 Data from the National Epidemiological Survey of Alcoholism and Related Conditions (NESARC) estimated a lifetime prevalence rate of 0.42% for pathological gambling5 and 0.2% past-year prevalence rate of pathological gambling, with an estimate of 0.7% for past-year problem/pathological gambling6. As subsyndromal forms of gambling (e.g., problem gambling) are more common than PG and also associated with adverse measures of functioning, additional research into a spectrum of gambling behaviors is warranted. 2,7,8

Researchers and clinicians have employed multiple definitions and terms for subsyndromal gambling, including problem, at-risk, and level 2 gambling.7,9–11 Current classification systems are largely based on clinical experience and expert consensus with few data-driven approaches providing empirical support for how best to group gambling behaviors. Analyses suggest that current strategies to distinguish subsyndromal from syndromal PG may not be using appropriate cut-points12 and distinct groups of individuals may exist within either subsyndromal or syndromal groups.13–17 For example, among individuals with PG, a more severe form has been associated with performance of illegal activities to support gambling.14,16 The existence of multiple terms and definitions for types of gambling behaviors increases the potential for conceptual confusion, makes comparisons of results across studies difficult, and hinders the development of effective prevention and treatment strategies. Thus, more research is needed into how best to classify gambling behaviors. Specifically, the use of data-driven approaches is warranted to investigate the structure of subsyndromal and syndromal gambling. Latent class analysis (LCA)18 is a technique that explores the underlying association among categorical items (symptoms or criteria) or manifest variables19,20 and may be understood as a categorical form of factor analysis. Although LCA has identified heterogeneity within other psychiatric disorders including depression,21 schizophrenia,22 and alcoholism,19 it has yet to be applied to PG. The application of LCA to PG criteria thus has the potential to provide empirical support for groups of gamblers based on PG criteria.

The co-occurrence between PG and other psychiatric disorders is substantial and has important clinical implications.23, 24 In community samples, PG co-occurs with multiple psychiatric conditions including psychotic, internalizing, externalizing and Axis II disorders, and this pattern of association extends to subsyndromal gambling.23,25,26 Individuals with PG and co-occurring disorders respond preferentially to specific therapies,24,27 and treatment algorithms for PG based on co-occurring disorders have been proposed.24,28 These data suggest that proposed classification systems for PG and subsyndromal gambling consider the relationship between identified classes and non-gambling psychiatric disorders.

Members of the Vietnam Era Twin Registry (VETR), a large community sample of male twins who served during the Vietnam military period, were surveyed for psychiatric disorders as described previously.11,29–31 These data are examined here by applying LCA18 to inclusionary criteria for PG. We hypothesized that: 1) multiple empirically derived classes based on PG criteria would be identified; 2) individual criteria would be differentially associated with specific classes; and 3) non-gambling psychopathology would be more frequently observed in classes characterized by higher frequencies of PG criteria acknowledgment.

METHODS

Subjects

The VETR is comprised of male-male twin pairs who served in the military during the Vietnam era.32–34 In 1992, approximately 10,300 VETR members were invited to participate in the “Twin Study of Drug Abuse and Dependence”.35 Our analyses include 8,138 of these twins for whom data were available. At least one DSM-III-R PG criterion was endorsed by 7.6% (95% confidence interval (CI): 7.0 – 8.3) of this sample; 1.4% (95% CI: 1.1 – 1.7) met criteria for DSM-III-R PG. Sociodemographic characteristics of our sample reflected the composition of the VETR;36 the mean age of participants was 43 years (range 36 – 49), and the great majority were non-Hispanic white (93%), employed full or part time (96%), married/widowed (76%), and had at least a high school education (96%).

Data Collection

A computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) adaptation of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version 3, Revised (DIS-III-R)37 was utilized to assess lifetime psychiatric histories. The DIS-III-R is a structured psychiatric interview with established reliability and validity that has been widely used for deriving DSM-III-R psychiatric diagnoses in epidemiologic studies. 38,39 Informed consent was obtained from all participants by trained interviewers, as approved by the Institutional Review Boards of participating institutions.

All respondents completed a three-item DIS-III-R-based screen: 1) “Have you ever gambled or bet or bought a lottery ticket or used a slot machine?”; 2) “Have you done these things more than five times in your life?”; and 3) “Have you ever gambled or bet or bought a lottery ticket or used a slot machine 25 or more times within one year?” This screen was intended to reduce respondent burden by not further assessing those individuals whose gambling behaviors were unlikely to reach the PG threshold. Respondents endorsing all three questions were assessed for PG.

Data Analysis

Identifying Latent Classes

We applied LCA to determine the number of latent classes that best accounted for observed patterns of covariation in gamblers’ lifetime endorsements of DSM-III-R PG criteria and investigate whether the data supported qualitative and/or quantitative differences among classes.40–42 In LCA, each respondent receives a membership probability for each mutually exclusive class based on the profile of symptoms endorsed and is assigned to the class with the highest probability. The LCA modeling procedure produces criterion endorsement probabilities (CEPs) that reflect the likelihood that a criterion is endorsed, given membership in a particular class. The profile of CEPs is constant for all members of each latent class and ensures that individuals with the same patterns of criteria endorsements are assigned to one and only one class. LCA considers both the number of criteria endorsed and the overall pattern of criterion endorsement. Since LCA accounts for the structure of the relationships among criteria, the methodology permits a more detailed specification of the nature of gambling behavior than is possible if gamblers are differentiated only by the number of PG criteria endorsed. In contrast to the DSM categorization in which an individual either meets or does not meet criteria for PG, the LCA performed here is not restricted by a priori assumptions about the precise number of gambling classes (i.e., latent classes) that would be defined or the nature of the differences between the classes, beyond the use of the DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria used as the basis for the analysis.

Respondents included in the LCA models were the 2,720 gamblers (approximately 33% of respondents) who endorsed all three screening questions. The remaining 5,418 individuals who screened negatively were classified as low-frequency/non-gamblers and not included in the LCA. We employed the Latent GOLD Program43 which uses the method of maximum likelihood while accounting for the twin clustering nature of the data to fit latent class models to the nine DSM-III-R PG criteria. Therefore, CEPs were interpreted as criterion prevalence for a given class. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)44,45 a goodness-of-fit index, was used to examine the null hypothesis (i.e., a one-class model) and alternative hypotheses (i.e., multi-class models). The BIC compares models and identifies the one that best fits the data (i.e., has the smallest BIC value). It is structured to make it increasingly difficult to accept alternatives of greater complexity (i.e., models with additional classes, see Posada & Buckey46 for additional details).

Examining Characteristics of LCA-Defined Classes

Chi-squares assessed the overall relationship between the LCA-defined classes and psychiatric history. We computed odds ratios (adjusted for sociodemographic variables that were significantly associated with the classes) using logistic regression models to quantify the likelihood that members of each LCA-defined gambling class had experienced non-PG psychiatric disorders in their lifetimes (compared with the baseline class of low-frequency/non-gamblers). Individual and total numbers of lifetime psychiatric disorders were examined. Nicotine dependence was excluded from the measure of total number of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses given the substantial changes in knowledge about the health risks associated with smoking during the lifetimes of the VETR members and the high rates of tobacco smoking in the military at the time of service. In order to explore how psychiatric disorders were related to memberships in the LCA classes vs. the DSM-based PG grouping, chi-square analyses were used to identify differences between pathological gamblers (PGers) assigned to different LCA-based gambling classes, and between PGers and non-PGers assigned to the same LCA-defined class. Chi-square and logistic regression analyses were conducted using STATA47 so that p-values and 95% CI accounted for non-independence of observations on family members.

RESULTS

Sample Prevalence of DSM-III-R PG Criteria

Prevalences of each DSM-III-R PG criterion for the sub-group included in the LCA (n = 2,720) are presented in Table 1. The prevalence range over all criteria 0.01 – 0.12 for the latent class sample.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of DSM-III-R PG criteria

| DSM-III-R PG Criterion | Prevalence (%) for Latent Class Sample (n=2,720) |

Prevalence (%) for Total Sample (n=8,138) |

|---|---|---|

| Frequent preoccupation with gambling or obtaining money to gamble | 8 | 3 |

| Frequent gambling of larger amounts of money or over a longer period of time than intended |

10 | 3 |

| A need to increase the size or frequency of bets to achieve the desired excitement |

5 | 2 |

| Restlessness or irritability if unable to gamble | 4 | 1 |

| Repeated loss of money by gambling and returning another day to win back losses (‘chasing’) |

12 | 4 |

| Repeated efforts to reduce or stop gambling | 10 | 3 |

| Frequent gambling when expected to meet social or occupational obligations |

2 | 1 |

| Sacrifice of some important social, occupational, or recreational activity in order to gamble |

1 | 0.4 |

| Continuation of gambling despite inability to pay mounting debts, or despite other significant social, occupational, or legal problems that the person knows to be exacerbated by gambling |

2 | 1 |

Identifying Latent Classes

Seven LCA models (i.e., 1-class through 7-class) were developed and tested. The 3-class model best fit our data (Table 2). Consequently, the baseline class (C0) of low-frequency/non-gamblers and three classes (C1-C3) of gamblers identified by the LCA were included in our final model.

Table 2.

Model assessment of LCA on PG criteria

| Model | −2log likelihood | BIC | Change in BIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 - class | 10336.73 | 10407.91 | 0 |

| 2 - class | 7885.19 | 8035.45 | −2372.460 |

| 3 - class | 7613.38 | 7842.72 | −2565.19 |

| 4 - class | 7571.81 | 7880.23 | −2527.68 |

| 5 - class | 7552.62 | 7940.13 | −2467.78 |

| 6 - class | 7530.43 | 7997.02 | −2410.89 |

| 7 - class | 7512.56 | 8058.24 | −2349.67 |

PG Criteria Endorsed by Each Class

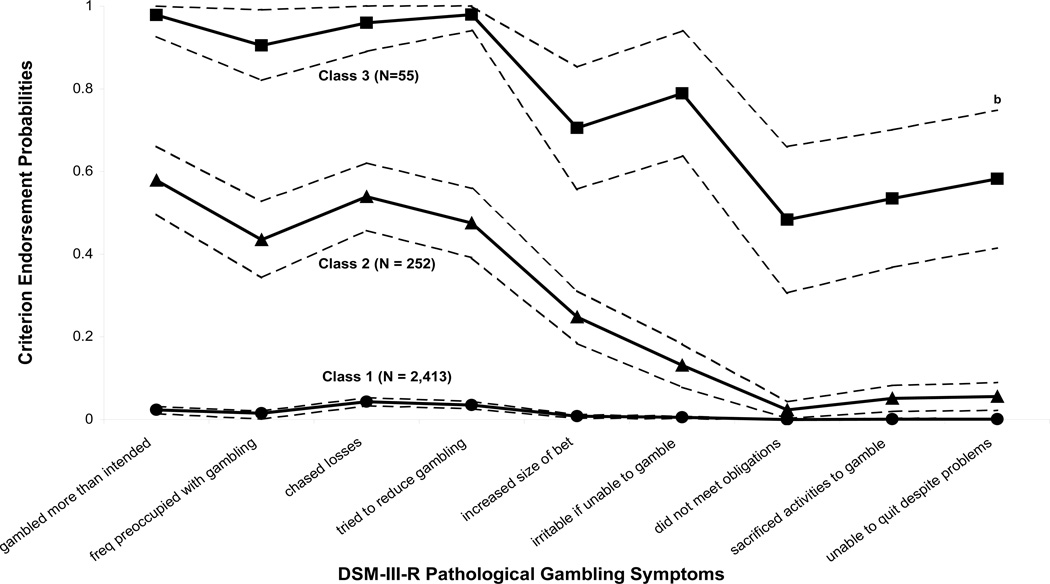

The proportions of subjects in classes C1-C3 acknowledging PG criteria are shown (Table 3, Figure 1). Few members of C1 endorsed any criteria of PG, and those who endorsed any endorsed no more than one criterion. In contrast, all members of C3 met diagnostic criteria for PG. Approximately equal numbers of subjects with PG were found in C2 and C3, although only 24% of subjects in C2 met criteria for PG. However, there was virtually no overlap between C2 and C3 as only two members of C3 endorsed as few as five criteria of PG, the maximal number acknowledged by any C2 members.

Table 3.

DSM-III-R pathological gambling (PG) criteria characteristics of members of the three classes defined by the latent class analysis (Classes 1 – 3)

| Class | Percentagea (n) of Total Sample1 |

PG Criterion Prevalence (range for all 9 symptoms) |

# of PG Criteria Endorsed (range) |

Proportion (n) Endorsing Indicated # of DSM-III-R PG Criteria |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1–33 | ≥ 4 (PG)4 | ||||

| 1 | 29.7%(2413) | 2%–6% | 0–1 | 87%(2,092) | 13%(321) | 0% |

| 2 | 3.1% (250) | 4%–58% | 2–5 | 0% | 76% (190) | 24% (60) |

| 3 | 0.68% (57) | 53%–100% | 5–92 | 0% | 0% | 100% (57) |

Total number of participants in entire sample was 8,138.

Only two members of this class endorsed 5 criteria.

Individuals endorsing 1–3 PG criteria are sometimes classified as “problem gamblers”.

Individuals endorsing ≥ 4 PG criteria meet the DSM-III-R definition of PG

Figure 1. LATENT CLASS ANALYSIS 3-CLASS SOLUTIONa.

aThis figure does not include Class 0 which consists of all individuals who had not gambled 25 or more times in a year, were not included in the latent class analysis, and were assumed to have no lifetime DSM-III-R pathological gambling criteria. Therefore, by definition, the criterion endorsement probabilities for all nine DSM-III-R PG symptoms for Class 0 are equal to zero.

bDotted lines represent the 95% confidence intervals around the individual values.

Non-overlapping 95% CIs around the criterion endorsement probability (CEP) estimates demonstrate that Classes 1, 2 and 3 are significantly different from each other (Figure 1). Whereas no individual criteria were endorsed at rates of greater than 6% among C1 members, criteria endorsed by more than 10% of C2 members included gambling more than intended (57%), preoccupation with gambling (43%), chasing (54%), attempts to reduce gambling (47%), gambling more over time (25%), and irritability when not gambling (13%). These and the remaining criteria for PG were more frequently endorsed by members of C3. Among the remaining criteria, many C3 members reported not meeting obligations because of gambling (48%), sacrificing activities because of gambling (53%), and being unable to quit gambling despite problems (58%). Together, these data suggest a gambling severity continuum with class 3 representing the most severe end of the spectrum.

Sociodemographic Characteristics Associated with Gambling Classes

Significant associations existed between the four-class typology and age, race, education, annual household income, marital status, and employment status (Table 4). Individuals with more severe gambling problems were more likely to be under 44 years of age, non-Caucasian, have less than a high school education, have an annual household income less than $35,000, and less likely to be married/widowed or employed.

Table 4.

Sociodemographic characteristics of members of the three gambling classes defined by the latent class analysis (Classes 1 – 3) plus the baseline class (Class 0)

| Characteristic | Class 0a(n=5418)b % (N) |

Class 1 (n=2413) b % (N) |

Class 2 (n=250) b % (N) |

Class 3 (n=57) b % (N) |

p valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged | |||||

| ≥ 44 years | 48% (2,594) | 47% (1,141) | 58% (144) | 53% (30) | p = 0.03 |

| ≥ 44 years | 52% (2,824) | 53% (1,272) | 42% (106) | 47% (27) | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 93% (5,038) | 95% (2,292) | 88% (220) | 81% (46) | p < 0.0001 |

| Non-white | 7% (378) | 5% (121) | 12% (30) | 18% (11) | |

| Education | |||||

| < high school | 4% (181) | 3% (78) | 6% (14) | 8% (4) | p < 0.0001 |

| high school grad | 30% (1,533) | 35% (821) | 38% (88) | 31% (16) | |

| some college | 42% (2,151) | 42% (964) | 44% (102) | 46% (24) | |

| college grad + | 25% (1,300) | 20% (453) | 12% (29) | 15% (8) | |

| Household Incomee | |||||

| ≥ $35,000 | 55% (2,750) | 53% (1,208) | 64% (146) | 59% (29) | p = 0.01 |

| ≥ $35,000 | 46% (2,296) | 47% (1,074) | 36% (81) | 41% (20) | |

| Marital Status | |||||

| married/widowed | 78% (4,249) | 74% (1,776) | 62% (155) | 61% (35) | p < 0.0001 |

| separated/divorced | 15% (788) | 18% (433) | 25% (63) | 28% (16) | |

| never married | 7% (381) | 8% (204) | 13% (32) | 11% (6) | |

| Employment Status | |||||

| full or part-time | 96% (5,014) | 96% (2,256) | 95% (219) | 80% (41) | p < 0.0001 |

| other | 4% (216) | 4% (103) | 5% (12) | 20% (10) |

Individuals in Class 0 had never gambled 25 or more times in a year, were assumed to have no PG symptoms, and were not included in the latent class modeling procedure.

Category n’s may not add up to Class n’s due to missing data.

X2 test of association.

Median age = 44.

Median income = $35,000.

Relationships with Other Psychiatric Disorders

The prevalence of lifetime psychiatric disorders increased across all four classes for all 11 illnesses examined except panic disorder (which only affected two members of C3), as did the total number of lifetime non-PG non-tobacco psychiatric diagnoses (Table 5, 6). For example, 45% of C3, but only 7% of C0 experienced three or more non-tobacco-related non-PG psychiatric disorders in their lifetimes. The overall association between the LCA typology and co-occurring psychopathology was significant for all illness definitions in Table 5. The logistic regression models revealed that members in C2 and C3 as compared to members of C0 were significantly more likely to experience all of the psychiatric disorders, with the exception of bipolar disorder for C2 (Table 6). Membership in C1 relative to C0 was positively associated with major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol dependence, nicotine dependence, conduct disorder, and drug dependence. As reflected in non-overlapping 95% CIs for odds ratios, members in C1 were less likely to report: 1) dysthymia, major depression, antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), conduct disorder, drug dependence, alcohol dependence, and nicotine dependence than were members in C2 and C3; 2) panic disorder and PTSD then were members in C2; and, 3) bipolar disorder and anxiety disorder than were members in C3. Members in C2 and C3 were essentially no different in their likelihood to meet criteria for individual psychiatric disorders, with the exception of bipolar disorder. Together, these data suggest that each gambling class has a progressively increased risk for non-gambling psychopathology across a broad range of psychiatric disorders.

Table 5.

Association between lifetime DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders and the three gambling classes defined by the latent class analysis (Classes 1 – 3) plus the baseline class (Class 0)

| DSM-III-R Diagnosis | Class 0a (n=5418) |

Class 1b (n=2413) |

Class 2b (n=250) | Class 3b (n=57) | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence%e (n) |

Prevalence %e (n) |

Prevalence %e (n) |

Prevalence %e n) |

||

| Bipolar Disorder | 0.5 (27) | 0.5 (13) | 1.2 (3) | 8.8 (5) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 1.3 (68) | 1.6 (38) | 3.2 (8) | 8.8 (5) | <0.0001 |

| Panic Disorder | 1.6 (88) | 1.6 (39) | 5.2 (13) | 3.5 (2) | 0.0003 |

| Dysthymia | 2.1 (112) | 2.4 (58) | 5.6 (14) | 10.5 (6) | <0.0001 |

| ASPD | 2.2 (120) | 2.8 (68) | 11.2 (28) | 19.3 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Conduct Disorder (CD) | 7.0 (378) | 8.7 (210) | 21.2 (53) | 33.3 (19) | <0.0001 |

| Drug Dependenced | 8.3 (448) | 10.6 (255) | 22.1 (55) | 33.3 (19) | <0.0001 |

| Major Depression | 8.6 (465) | 10.6 (256) | 18.8 (47) | 35.1 (20) | <0.0001 |

| PTSD | 9.0 (487) | 11.2 (269) | 20.6 (51) | 21.4 (12) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol Dependence | 31.3 (1,690) | 42.1 (1,014) | 66.3 (165) | 68.4 (39) | <0.0001 |

| Nicotine Dependence | 43.4 (2,350) | 54.8 (1,322) | 64.4 (161) | 78.9 (45) | <0.0001 |

| Number of non-PG disordersf | <0.0001 | ||||

| None | 58.6 (3,173) | 47.0 (1,135) | 23.8 (60) | 9.1 (5) | |

| Any 1 | 25.5 (1,381) | 32.1 (775) | 32.9 (83) | 30.9 (17) | |

| Any 2 | 9.1 (493) | 11.8 (284) | 20.0 (51) | 14.6 (8) | |

| Any 3 or more | 6.9 (371) | 9.1 (219) | 23.0 (58) | 45.4 (25) |

Individuals in Class 0 had never gambled 25 or more times in a year, were assumed to have no PG symptoms, and were not included in the latent class modeling procedure.

Classes 1 – 3 were defined by the 3-class latent class analysis model

χ2 test with three degrees of freedom, calculated separately for each disorder.

Includes marijuana, sedatives, stimulants, heroin/opiates, PCP/psychedelics

Lifetime prevalence = % among individuals in that class

Count includes all psychiatric disorders listed in the table except nicotine dependence. ASPD and CD are counted as separate disorders if an individual experienced both of them.

Table 6.

Association (odds ratio (95% confidence interval))a between lifetime DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders and the three gambling classes defined by the latent class analysis (Classes 1 – 3) plus the baseline class (Class 0)

| DSM-III-R Diagnosis | Class 1 vs. Class 0 | Class 2 vs. Class 0 | Class 3 vs. Class 0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar Disorder | 1.3 (0.7, 2.7) | <0.01(<0.01,<0.01) | 10.5 (2.3, 48.7) |

| Anxiety Disorder | 1.2 (0.7, 1.8) | 2.5 (1.1, 6.0) | 11.3 (4.5, 28.1) |

| Panic Disorder | 1.2 (0.8, 1.8) | 3.6 (1.8, 7.3) | 1.6 (0.2, 11.3) |

| Dysthymia | 1.2 (0.9, 1.8) | 2.8 (1.5, 5.4) | 5.9 (2.2, 16.0) |

| ASPD | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) | 5.4 (3.3, 8.9) | 9.9 (4.3, 23.0) |

| Conduct Disorder | 1.4 (1.1, 1.7) | 3.6 (2.5, 5.2) | 7.1 (3.7, 13.8) |

| Drug Dependenceb | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 2.8 (2.0, 4.1) | 4.3 (2.1, 9.0) |

| Major Depression | 1.2 (1.1, 1.5) | 2.0 (1.3, 2.9) | 5.7 (3.0, 11.0) |

| PTSD | 1.4 (1.2, 1.6) | 2.2 (1.5, 3.2) | 2.5 (1.2, 5.3) |

| Alcohol Dependence | 1.6 (1.4, 1.7) | 3.4 (2.6, 4.6) | 4.5 (2.3, 8.7) |

| Nicotine Dependence | 1.5 (1.4, 1.7) | 2.0 (1.5, 2.6) | 3.6 (1.8, 7.1) |

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logistic regression model adjusting for age, race income, education, employment, and marital status.

Includes marijuana, sedatives, stimulants, heroin/opiates, PCP/psychedelics

Relationships with Psychiatric Disorders: LCA Class Membership and DSM-Based PG

Individual psychiatric disorders among PGers in C2 as compared to PGers in C3 were statistically different at p<0.05 for nicotine dependence (C2: 59.7% vs C3: 78.2%, X2 = 5.56, p = 0.02), ASPD (C2: 4.8% vs C3: 20.0%, X2 = 5.57, p = 0.02), and conduct disorder (C2: 11.3% vs C3: 34.6%, X2 = 7.88, p = 0.006). Among C2 members, similar proportions of PGers and non-PGers met criteria for each psychiatric disorder with only conduct disorder showing a between-group difference at p<0.05 (non-PGers: 24.2% vs PGers: 11.3%, X2 = 4.24, p = 0.04). Since C2 was the only class that included both PGers and non-PGers, this was the only class for which this comparison could be made. Together, these data suggest that psychiatric differences exist between PGers in classes C2 and C3 and that PGers and non-PGers in C2 have largely similar psychiatric concerns.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to our knowledge to apply LCA to criteria for PG. The identification of four classes of gamblers, one class comprised of low-frequency/non-gamblers and three identified via LCA, has significance for how best to conceptualize PG and subsyndromal gambling. The findings that individual PG criteria and non-gambling psychiatric disorders were differentially associated with the four classes have clinical implications.

Identifying Latent Classes

Each LCA-defined gambling class was associated with increasing severity of gambling-related problems. The C1, C2 and C3 groups were distinguished by the number of PG criteria endorsed, prevalence of each PG criterion, and estimated PG prevalence, and these findings are consistent with a gambling severity continuum. Similarities were observed between the VETR and other previously described community samples. For example, ‘chasing losses’ was the most frequently endorsed symptom across classes and was frequently acknowledged by less severe gambling groups, consistent with findings from other studies.16 Other criteria, specifically those relating to the most severe interference in major areas of life functioning (not meeting obligations, sacrificing activities, and feeling unable to quit despite problems) were among those acknowledged almost exclusively by members of C3. These criteria are arguably those most characteristic of addiction.48,49 Although C2 contained a substantial number of individuals with DSM-III-R defined PG, the overlap in criteria count between members of C2 and C3 was small, with only 2 members of C3 having as few as five PG criteria. Thus, a criteria count of six or more to define the most severely interfering form of gambling behaviors would be largely consistent with the groups defined by the LCA. The use of different thresholds of inclusionary criteria for DSM-IV PG to define subgroups of PGers has been suggested based on data from the Gambling Impact and Behavior Study (GIBS).16 As with findings from the LCA analysis of VETR data, analyses of the GIBS data indicate that specific criteria more closely associated with addiction pathology (e.g., engagement in illegal behaviors to support gambling and risking or losing important relationships or occupational opportunities) are distinctly associated with a more severe subgroup of individuals with PG. Together, these data suggest that a definition of a more severe form of gambling representing the extreme end of the current PG continuum be considered in future editions of the diagnostic and statistical manual.1,49,50

Data suggest that PG and substance use disorders (e.g., substance abuse and dependence) share similar features.49,50 The existence of two diagnostic groupings for excessive patterns of substance use behaviors (abuse and dependence) raises the question as to whether analogous groupings should be used for gambling behaviors, consistent with other models.10 Data from the current LCA suggest that two groups of problematic gambling behaviors could be considered. Specifically, groups C2 and C3 exhibit significant patterns of endorsement of PG criteria that are different from non-gamblers and gamblers infrequently reporting PG criteria (groups C0 and C1). A threshold of 2–5 DSM-III-R inclusionary criteria for the C2 group is suggested by the results of the LCA as this threshold largely distinguishes the C2 group from C1 and C3 members. Compared to the C0 and C1 groups, the C2 group more frequently acknowledges multiple PG criteria including those currently found in the DSM-IV criteria for PG that mirror the inclusionary criteria for substance dependence; e.g., aspects of tolerance (i.e., DSM-III-R ‘needing to increase size of bet to maintain excitement’) and withdrawal (i.e., DSM-III-R ‘irritable when unable to gamble’). Although approximately 24% of C2 members met clinical criteria for PG, PG and non-PG members of C2 had largely similar features with respect to co-occurring psychiatric disorders, and differences in co-occurring psychiatric disorders between C2 and C3 appeared more substantial those between PG and non-PG C2 members (see discussion below). Taken together, these findings suggest that the LCA results may be used to better categorize distinct groups of gamblers with respect to both gambling behaviors and co-occurring psychiatric concerns. With respect to the C3 group, the C2 group exhibits fewer and less interfering gambling problems that are nonetheless clinically significant. Thus the C2 group may be analogous to “gambling abuse” and the C3 group analogous to “gambling addiction” or “gambling dependence”. More research is warranted to examine this possibility, particularly given the implications for diagnosis, prevention and treatment of interfering patterns of gambling behaviors. In particular, analyses focusing on DSM-IV criteria that include additional items (e.g., one targeting “escape” gambling that is particularly salient to women with gambling problems [49]) are warranted.

The relationship of individual criteria of PG to the LCA-defined classes warrants consideration. The LCA suggests a hierarchy of clinical features (see Figure 1) consistent with published reports of PG criteria prevalence, gambling progression in treatment populations and the distinction between abuse and dependence established for substance use disorders.52–54 ‘Gambling more than intended’ and ‘chasing losses’ are prevalent even in those demonstrating few problematic behaviors related to gambling,16 suggesting that they are “mild” PG behaviors, early features of PG, perhaps associated with ‘abuse’ rather than ‘dependence’. ‘Trying to reduce gambling’, ‘frequent preoccupation with gambling’, ‘increasing the size of the bet’, and ‘irritability when not gambling’ could be considered behaviors associated with ‘loss of control’ and ‘dependence’ (e.g., withdrawal, tolerance, etc.),55 and might represent greater severity of gambling problems or a later stage of PG. Being ‘unable to quit despite problems’, ‘not meeting obligations’, and ‘sacrificing activities for gambling’ are features of an addiction that are likely to appear after gambling has caused severe life impairment that profoundly impacts the gambler’s relationships and obligations,56 and might indicate the most advanced form of PG. The suggested hierarchy of clinical features has diagnostic implications for defining clinical populations and thus may help refine existing prevention and treatment strategies. Additionally, longitudinal studies could examine the extent to which individuals progress temporally through “mild”, “abuse”, and “dependence/addiction” criteria over time.

The investigation of individual criteria via LCA permitted identification of qualitative differences among classes. Although significant differences in CEPs among classes were observed, an important feature was that certain criteria distinguished the gambling classes in CEP magnitudes. Mild PG behaviors differentiated C1 and C2; approximately half of the C2 gamblers endorsed “mild behaviors” and approximately a third endorsed “dependence” criteria. In general, although some C2 gamblers exhibited loss of control over their gambling, their societal and personal relationships and obligations appeared largely unaffected. By comparison, almost all C3 gamblers endorsed all mild behavioral and dependence criteria. However, the distinctive feature of C3 was the endorsement of life impairment criteria, suggesting that PGers’ lives in C3 were dominated by gambling behavior and its consequences. This interpretation of the clustering of PG criteria has clinical implications for consideration of gambling pathology in the upcoming DSM-V, e.g., the potential utility of considering multiple diagnostic categories for gambling and differentially weighting criteria when classifying gambling problems.

Although our interpretation is exploratory in nature, it is consistent with Toce-Gerstein et al.’s findings,16 in which DSM-IV ‘withdrawal’ and ‘loss of control’ differentiated ‘problem gamblers’ from ‘low-severity PGers’. In our study, the corresponding DSM-III-R criteria (‘irritability when unable to gamble’, ‘tried to reduce gambling’) differentiated C2 and C1. ‘Risked job or other significant relationship’ and ‘committed one or more illegal acts to finance gambling ventures and losses’ were DSM-IV criteria that differentiated Toce-Gerstein’s ‘high-severity’ and ‘low-severity’ PGers. The most closely relevant DSM-III-R symptoms in this study, those indicating life impairment, differentiated the C3 and C2 groups. Toce-Gerstein et al. concluded that the association of different groupings of DSM-IV criteria with gambling categories indicated that qualitative differences existed concomitant with a severity continuum.

Relationships with Psychiatric Disorders

Consistent with previous reports,23–25 we found an overall association between our typology and prevalence of psychopathology, i.e., increasing gambling severity was associated with higher prevalence of individual co-occurring lifetime disorders as well as the total number of non-PG non-tobacco psychiatric disorders experienced in the respondent’s lifetime. However, in our data, since there were no significant differences between C2 and C3, the association appears predominantly driven by significant differences between C0 and C1, and the ways in which C0 and C1 were significantly different than C2 and C3. Significant differences were observed between C0 and C1 groups in rates of many psychiatric disorders including conduct disorder, major depression, PTSD, drug dependence, alcohol dependence, and nicotine dependence. The finding that low level or recreational gambling is associated with increased odds for multiple psychiatric disorders is consistent with findings from the GIBS.57–59 Given the cross-sectional nature of this study and limited personal information gathered (e.g., with respect to personality or neurocognitive/behavioral functioning), the nature of this association remains unclear. Nonetheless, the findings reinforce the importance of further studying subsynromal levels of gambling with respect to co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

Of potential interest is the consistency of our findings with Blaszczynski et al.’s identification of an ‘anti-social impulsivist’ PG sub-type,60 and with Blaszczynski and Nower’s conceptualization of the etiological role of anti-social and impulsive behavior in the development of a PG sub-type characterized by emotional vulnerabilities combined with severe maladaptive behaviors that influence many aspects of the gambler’s general level of psychosocial functioning.61 Along with nicotine dependence, ASPD and conduct disorder were more significantly associated with C3 than with C2. As ASPD and conduct disorder are typically characterized by a tendency to neglect responsibilities and/or commit illegal behaviors, these features when combined with impaired control over one’s gambling may result in more severe gambling pathology. The possibility that behaviors related to conduct disorder extend into gambling behaviors might explain the lower frequency of conduct disorder in PGers vs. non-PGers in C2. As environmental and genetic factors common to PG and antisocial behaviors have been reported using data from the VETR,31 further study of additional samples are warranted to identify specific environmental and genetic contributions to their co-occurrence, particularly given the apparent relationship between more severe gambling pathology and antisocial behaviors.62

Although there are limitations in the ability to validate the identified typology with the existing data, the association of the LCA-defined groups with increases in the total number of endorsed criteria, prevalence of each criterion and prevalence of co-occurring lifetime psychopathology are consistent with the extant literature demonstrating a severity continuum of gambling problems. The similarity of our findings regarding the clustering of symptoms with the work of Toce-Gerstein et al. and regarding the role of antisocial behaviors with Blaszczynski and Nower’s ‘pathways model’ support the qualitative characteristics of our typology and suggest its generalizability to other samples.

Implications for Future Research

The identification of quantitative and qualitative differences among gamblers emphasizes the need to consider the heterogeneity of gambling behaviors when conducting research, creating treatment protocols, and developing policy. Expanding upon Blaszczynski and Nower’s ‘pathways model’ for PG to include the etiology of sub-clinical gambling problems could result in intervention strategies aimed at a larger proportion of individuals experiencing problems with their gambling behaviors. Such strategies might lead to earlier identification than is currently available using more stringent diagnostic criteria and thus could have a substantial public health impact. Targeting groups of gamblers with specific characteristics likely would result in more effective prevention and treatment efforts. For example, variable results of outcome studies reflect disparities in the distribution of groups of gamblers with different treatment responses.63 Studies permitting separation of gamblers with different gambling experiences are likely to yield more conclusive findings. An improved ability to distinguish gamblers most likely to experience excessive costs (i.e., negative consequences) of gambling from those less likely to experience gambling problems could also have significant public health benefits. That both Toce-Gerstein et al.’s and our studies, with their different methodologies and sample characteristics, found evidence of qualitative differences within a severity continuum inclusive of 2-levels of PG is noteworthy. These studies, together with the extant body of literature, suggest the importance of considering subsyndromal PG symptomatology, qualitative differences among individuals with gambling problems, and the role of co-occurring psychiatric disorders when assessing the public health implications of gambling.

Two issues are particularly salient in light of the upcoming DSM-V. Currently, all PG criteria are equally weighted. The likely improvement in diagnostic methodology resulting from differential weighting of DSM criteria has been noted for other psychiatric disorders64–66 and appears relevant for PG. Assigning a small weight to mild PG behaviors, greater weight to physiological dependence criteria, and the greatest weight to life impairment criteria might result in a more precise diagnostic classification system. For example, the 24% of C2 with PG might not have met the clinical threshold if weighted criteria were used, thus potentially creating a clearer distinction between C2 and C3. Toce-Gerstein et al. identified similar clusters of criteria that might be highly predictive of different patterns of gambling.16,17

Secondly, the growing body of evidence supporting both a severity continuum of gambling problems10,11,16,67,68 and qualitative differences between PG sub-types16,61,69–71 argues for expanding PG classification in the DSM. Incorporating sub-clinical PG would help standardize the definition of ‘problem gambling’, while specification of PG subtypes (e.g., based on clinical characteristics such as co-occurrence of ASPD) could have significant implications for treatment protocols. Even in the absence of changes in the DSM, much could be gained if clinicians and researchers actively investigate the heterogeneity of gambling behaviors and the unique characteristics of groups of gamblers when estimating prevalence, assessing risk, interpreting research findings, and evaluating treatment and policy options.

Strengths and Limitations

The major strength of our study is the identification of both quantitative and qualitative differences among treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking gamblers using a data-driven methodology. We identified an empirically-based typology of largely mutually exclusive gambling classes by applying LCA to a community-based sample with a broad range of gambling experiences, without making a priori assumptions about the number of classes that would be found or differences between them. A significant aspect of the utility of this typology is its derivation from a few variables that are easily obtained in both clinical and research settings.

The primary limitations of our study result in part from the source of our sample, the VETR. Because our cohort was entirely male, of a narrow age range (35–53 years old), included only a small proportion of non-Caucasians (7.0%), and was not asked about age at gambling onset, we were unable to examine the relationship between these characteristics and gambling behavior. Therefore, although the consistency of our findings with other published studies supports the generalizability of our typology, it may not apply to women, other age groups, minorities, or non-veterans. Self-reported responses to gambling questions derived from the DSM-III-R may lead to under-reporting of gambling involvement;72,73 however, we were unable to independently corroborate self-reports of gambling-related behaviors. Individual criteria for PG might relate to the disorder in multiple and complex manners; e.g., “trying to reduce gambling” might reflect severity of gambling, individual insight into the impact of the gambling, availability of treatment venues or other factors. In addition, the use of the three-question screen for assessment of PG might have precluded the identification of PG symptoms in some individuals. The sample contained a relatively small number of individuals with PG and membership in the C3 class. Although the proportions of PG subjects are consistent with those in other community samples,16,23,25 the small number of PG subjects provided limited power for some comparisons.

Other limitations are related to the survey design. Cross-sectional studies by their nature are limited in investigating causality and thus do not directly address temporal patterns in the relationships between gambling and co-occurring disorders and behaviors. Due to our data collection methodology and limitations in the types of data collected, we were unable to conduct more detailed investigations of: a) the temporal relationship between PG or LCA-defined gambling groups, PG criteria, and other psychiatric disorders (e.g., are high proportions of bipolar and alcohol use disorders in the C3 group related to excessive gambling during mania or intoxication, respectively, might gambling-related consequences lead to mood dysregulation or excessive alcohol use, or might common factors (for example, impulsive characteristics) lead to co-occurring behaviors/disorders); b) differences between respondents who never gambled and those who gambled less than 25 times in a year; and, c) social and environmental factors related to gambling (e.g., having parents who gamble, the gambler’s personality) or type of gambling activity that might further differentiate PG criteria endorsement patterns and influence class membership. For example, only playing the lottery on a weekly basis might not result in serious consequences to the gambler’s social and personal obligations, and thus may influence the pattern of criterion endorsement. Additional analyses incorporating factors such as treatment utilization are needed to further support the validity of this typology.

CONCLUSION

Empirical support is provided for a severity continuum of gambling behaviors incorporating qualitative differences among gamblers. Our typology offers an approach to categorizing heterogeneous gambling behaviors, and provides direction for research on the developmental progression of gambling problems and the utility of weighting symptoms when diagnosing PG. Additional studies using DSM-IV PG criteria and more sociodemographically heterogeneous samples are indicated.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DA04604, DA09447, DA019039, MH60426, AA00264 and AA11998 and the Veteran’s Affair Mental Illness Research Education Clinical Center and Research Enhancement Award Program.

Footnotes

Previous Presentation: Sixteenth National Council on Problem Gambling, Dallas TX, June 13–15, 2002 by Kamini Shah, MHS.

Location of Work: Research Service, St. Louis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, St. Louis, MO

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: 2000. Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerstein DR, Volberg RA, Toce MT, et al. Gambling Impact and Behavior Study. Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. Chicago IL: NORC at the University of Chicago; 1999. (the NORC final report can be permanently, accessed at http://cloud9.norc.uchicago.edu/dlib/ngis.htm) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ledgerwood DM, Steinberg MA, Wu R, et al. Self-reported gambling-related suicidality among gambling help line callers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:175–183. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welte J, Barnes G, Wieczorek W, et al. Alcohol and gambling pathology among U.S. adults: prevalence, demographic patterns and comorbidity. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:706–712. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nancy MPetry, Frederick SStinson, Bridget F Grant. Comorbidity of DSM-IV Pathological Gambling and Other Psychiatric Disorders: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Clin Psychiatry. 2005:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rani ADesai, Marc NPotenza. Gender differences in the associations between past-year gambling problems and psychiatric disorders. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0283-z. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potenza MN, Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ. Pathological gambling. JAMA. 2001;286:141–144. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: a research synthesis. Am J Public Health. 1999;86:1369–1376. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai RA, Maciejewski PK, Dausey DJ, et al. Health correlates of recreational gambling in older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1672–1679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaffer HJ, Korn DA. Gambling and related mental disorders: A public health analysis. Annu Rev Public. Health. 2002;23:171–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slutske WS, Eisen S, True WR, et al. Common genetic vulnerability for pathological gambling and alcohol dependence in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:666–673. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stinchfield R. Reliability, validity. and classification accuracy of a measure of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:180–182. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orford J. The fascination of psychometrics: Commentary on Gerstein et al (2003) Addiction. 2003;98:1675–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petry NM. Moving beyond a dichotomous classification for gambling disorders. Addiction. 2003;98:1673–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal RJ. Distribution of the DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling. Addiction. 2003;98:1674–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toce-Gerstein M, Gerstein DR, Volberg RA. A hierarchy of gambling disorders in the general population. Addiction. 2003;98:1661–1672. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toce-Gerstein M, Gerstein DR, Volberg RA. Where to draw the line? Response to comments on “A hierarchy of gambling disorders in the general population”. Addiction. 2003;98:1678–1679. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCutcheon AL. Latent Class Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Reich T, et al. Can we subtype alcoholism? A latent class analysis of data from relatives of alcoholics in a multicenter family study of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1462–1471. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH, et al. Nicotine withdrawal in women. Addiction. 1997;92:889–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan PF, Kessler RC, Kendler KS. Latent class analysis of lifetime depressive symptoms in the National Comorbidity Survey. Amer J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1398–1406. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castle DJ, Sham PC, Wessely S, et al. The subtyping of schizophrenia in men and women: a latent class analysis. Psychol Med. 1994;24:41–51. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700026817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Potenza MN. Impulse control disorders and co-occurring disorders: dual diagnosis considerations. J Dual Diagnosis. 2007;3:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB, Compton WM, 3rd, et al. Taking chances: Problem gamblers and mental health disorders - results from the St.Louis Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1093–1096. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.7.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desai RA, Potenza MN. Gender differences in the association between gambling problems and psychiatric disorders. Soc Psychol Psychiatric Epidemiol [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollander E, Pallanti S, Allen A, et al. Does Sustained-Release Lithium Reduce Impulsive Gambling and Affective Instability Versus Placebo in Pathological Gamblers With Bipolar Spectrum Disorders? Amer J Psychiatry. 2005;162:137–145. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.137. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hollander E, Kaplan, Pallanti S. Grant JE, Potenza MN. Pharmacological Treatments in Pathological Gambling: A Clinical Guide to Treatment. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 2004. pp. 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisen SA, Lin N, Lyons MJ, et al. Familial influences on gambling behavior: an analysis of 3359 twin pairs. Addiction. 1998;93:1375–1384. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93913758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potenza MN, Xian H, Shah K, et al. Shared genetic contributions to pathological gambling and major depression in men. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1015–1021. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slutske WS, Eisen S, Xian H, et al. A twin study of the association between pathological gambling and antisocial personality disorder. J Abnormal Psychol. 2001;110:297–308. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eisen S, True W, Goldberg J, et al. The Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry: method of construction. Acta Genet Med Gemellol. 1987;36:61–66. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000004591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisen S, Neuman R, Goldberg J, et al. Determining zygosity in the Vietnam Era Twin Registry: an approach using questionnaires. Clin Genet. 1989;35:423–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1989.tb02967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg J, True W, Eisen S, et al. The Vietnam Era Twin (VET) Registry: ascertainment bias. Acta Genet Med Gemellol. 1987;36:67–78. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000004608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyons M, True WR, Eisen SA, et al. Differential heritability of adult and juvenile antisocial traits. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:906–915. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950230020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson WG, Eisen S, Goldberg J, et al. The Vietnam Era Twin Registry: a resource for medical research. Public Health Report. 1990;105:368–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Cottler L, et al. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule Version III-Revised. St. Louis, MO: Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lachner G, Wittchen HU, Perkonigg A, et al. Structure, content and reliability of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI) substance use sections. Eur J Addictions. 1998;4:28–41. doi: 10.1159/000018922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatric Res. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasmussen ER, Neuman RJ, Heath AC, et al. Familial clustering of latent class and DSM-IV defined attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) subtypes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:589–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sacker A, Wiggins RD, Clarke P, et al. Making sense of symptom checklists: a latent class approach to the first 9 years of the British Household Panel Survey. J Public Health Med. 2003;25:215–222. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdg056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xian H, Scherrer JF, Madden PA, et al. Latent class typology of nicotine withdrawal: genetic contributions and association with failed smoking cessation and psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35:409–419. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Technical Guide for Latent GOLD 4.0: Basic and Advanced. Belmont, Massachusetts: Statistical Innovations, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W, Nyholt DR. Marker selection by Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion. Genet Epidemiol. 2001;21(Suppl 1):S272–S277. doi: 10.1002/gepi.2001.21.s1.s272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Posada D, Buckley TR. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: Advantages of Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Approaches over likelihood ration tests. Syst Biol. 2004;53:793–808. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.STATA Corporation. STATA Statistical Software: Release 7.0. College Station, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101:142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holden C. ‘Behavioral’ addictions: do they exist? Science. 2001;294:980–982. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5544.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petry NM. Should the scope of addictive behaviors be broadened to include pathological gambling? Addiction. 2006;101:152–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blanco C, Hasin DS, Petry NM, et al. Sex differences in subclinical and DSM-IV pathological gambling: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36:943–953. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beaudoin CM, Cox BJ. Characteristics of problem gambling in a Canadian context: a preliminary study using a DSM-IV/based questionnaire. Can J Psychiatry. 1999;44:483–487. doi: 10.1177/070674379904400509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lesieur HR, Rosenthal RJ. Pathological gambling: a review of the literature (prepared for the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on DSM-IV Committee on Disorders of Impulse Control Not Elsewhere Classified) J Gambling Stud. 1991;7:5–39. doi: 10.1007/BF01019763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenthal RJ, Lorenz VC. The pathological gambler as criminal offender Comments on evaluation and treatment. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15:647–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Research Council. Pathological Gambling A Critical Review, Chapter 4 Gambling Concepts and Nomenclature. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. pp. 15–62. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Custer R, Milt H. The Phases in the Life of the Compulsive Gambler. New York, NY: Factson File, Inc; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desai RA, Maciejewski PK, Pantalon MV, et al. Gender differences in adolescent gambling. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17:249–258. doi: 10.1080/10401230500295636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lynch WJ, Maciejewski PK, Potenza MN. Psychiatric correlates of gambling in adolescents and young adults grouped by age at gambling onset. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1116–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Potenza MN, Maciejewski PK, Mazure CM. A gender-based examination of the correlates of past-year recreational gambling. J Gamb Stud. 2006;22:41–64. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-9002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blaszczynski A, Steel Z, McConaghy N. Impulsivity in pathological gambling: the antisocial impulsivist. Addiction. 1997;92:75–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blaszczynski A, Nower L. A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction. 2002;97:487–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pietrzak RH, Petry NM. Antisocial personality disorder is associated with increased severity of gambling, medical, drug and psychiatric problems among treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. Addiction. 2005;100:1183–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Potenza MN. A perspective on future directions in the prevention, treatment, and research of pathological gambling. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:205–207. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carroll BJ. Problems with diagnostic criteria for depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984;45:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davis RT, Blashfield RK, McElroy RA., Jr Weighting criteria in the diagnosis of a personality disorder: a demonstration. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:319–322. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Widiger TA, Hurt SW, Frances A, et al. Diagnostic efficiency and DSM-III. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:1005–1012. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790210087011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abbott MW, Volberg RA. Report Number One of the New Zealand Gambling Survey. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Internal Affairs; 1999. Gambling and Problem Gambling: An International Overview and Critique. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ferris J, Wynne H. The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final Report. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blaszczynsk A, McConaghy N, Frankova A. Boredom proneness in pathological gambling. Psychol Rep. 1990;67:35–42. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1990.67.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chantal Y, Vallerand RJ, Vallieres EF. Motivation and gambling involvement. J Soc Psychol. 1995;135:755–763. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1995.9713978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moran E. Varieties of pathological gambling. Br J Psychiatry. 1970;116:593–597. doi: 10.1192/bjp.116.535.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.The Productivity Commission. Australia’s Gambling Industries Inquiry Report. Volume 1. Commonwealth of Australia: 1999. Report No. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Volberg RA. Prevalence studies of problem gambling in the United States. J Gamb Stud. 1996;12:111–128. doi: 10.1007/BF01539169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]