Abstract

Background

Older adults are particularly vulnerable to adverse events during hospitalization. The Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) service is a novel model of care designed to deliver specialized interdisciplinary care to hospitalized older adults in order to improve patient outcomes.

Methods

To evaluate the impact of the MACE service, we conducted a prospective, matched cohort study of patients aged 75 years or older admitted to a tertiary hospital for an acute illness to either the MACE service or medicine service (usual care). Patients were matched using age, diagnosis, and ability to ambulate independently. Patient outcomes included incidence of adverse events including falls, pressure ulcers, restraint use and catheter-associated urinary tract infections, length of stay (LOS), rehospitalization within 30 days, functional status at 30 days, and patient satisfaction during care transitions, measured using the 3-item Care Transition Measure (CTM).

Results

A total of 173 matched-pairs of patients were recruited. Average age was 85.2 (Standard Deviation [SD] 5.3) and 84.7 (SD 5.4) among MACE and usual care patients respectively. After adjusting for potential confounders, patients managed by the MACE service were less likely to experience adverse events (9.5% vs. 17.0%; Adjusted Odds Ratio [OR]: 0.11, 95% Confidence Interval [CI], 0.01-0.88; p=0.04) and had a shorter LOS (0.8 days, 95% CI, 0.7-0.9; p=0.001) when compared with patients receiving usual care. MACE patients were not less likely to have a lower rate of rehospitalization within 30 days when compared with usual care patients (OR 0.91, 95% CI, 0.39-2.10; p=0.83). Functional status was not different between the two groups. CTM-scores were 7.4 points (95% CI, 2.9-11.9; p=0.001) higher among MACE patients.

Conclusion

Admission to the MACE service was associated with lower complication rates, shorter LOS, and better satisfaction. This model has the potential to improve care outcomes among hospitalized older adults.

INTRODUCTION

Older adults are particularly vulnerable to adverse events during and following hospitalization for acute medical problems, including pressure ulcers, falls, hospital-acquired infections, functional decline, institutionalization and readmission to the hospital after discharge.1 As health care reform is underway, with incentives and penalties to hospital systems in an effort to reduce medical complications specifically related to care for older adults, also known as “never events”,2 geriatric-focused models of inpatient care offer effective ways to transform inpatient care for older adults. These models, staffed by geriatricians and others trained in delivering care for older adults, have been associated with better outcomes, such as reduced risk of institutionalization and functional decline.3,4 In the 1990s, the Acute Care for Elderly (ACE) unit was designed and tested for its potential to improve patient outcomes in randomized-controlled trials5-7 and is widely accepted as a prototype model to provide inpatient care for older adults.8,9 ACE units used a multidisciplinary approach to integrate principles of comprehensive geriatric assessment and quality improvement, incorporating a specifically designed hospital environment, patient-centered care, discharge planning and review of medical care to reduce avoidable adverse events.9 While unit-based care models have clear advantages for care, they have not been widely disseminated across institutions,10 particularly because of barriers in initial set up, including costs, staff and space.9,10 Furthermore, due to patient flow where hospitals often are at or near capacity and patient turnover is rapid, the physical ACE unit may not be able to hold out beds for patients for which the unit is designed, and there will be times when the unit is too full to accommodate patients deemed appropriate for the unit.11

As a result, we modified the ACE unit model of care at our institution to deliver geriatric-oriented inpatient care to older patients without the limitations of a physical unit. The Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) service consists of an interdisciplinary team of geriatricians, social workers and clinical nurse specialists with a focus on reducing the risks of hospitalization, improving care coordination with outpatient practice, discharge planning, and patient and caregiver education. In order to examine its effectiveness, we conducted a prospective study with a matched cohort design to examine for outcomes associated with the MACE service for hospitalized vulnerable older adults. We hypothesized that the MACE service, which included a transitional care component, may be associated with improved outcomes for hospital readmissions, adverse event incidence, length of stay, and patient satisfaction, when compared with usual care.

METHODS

This study was conducted at the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, NY, an urban tertiary care hospital, from November 2008 to August 2011. The MACE service was developed as an inpatient service to care for older adults who were receiving care at the outpatient geriatrics practice at Mount Sinai, a geriatrics patient-centered medical home delivering primary and geriatric care to older adults. These patients are routinely admitted to the MACE service during any inpatient admission at Mount Sinai for medical reasons. In order to evaluate its potential effects, we established a matching cohort drawing from patients admitted to the inpatient medical service using a prospective matching algorithm to reduce confounding from differences between the two populations of patients. This method has previously been used to establish balanced control group in previous studies.12,13 The study was approved by Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT00927160).

Description of MACE service and usual care

Briefly, the MACE service team consisted of an attending geriatrician-hospitalist, geriatric medicine fellow, social worker, and a clinical nurse specialist. The geriatricianhospitalist was the attending of record for the elderly patient admitted for acute care in the hospital. The interdisciplinary team met daily to discuss the care of all patients with the nurse specialist acting as the “hospital coach” educating the patient or caregiver. The MACE service also adopted elements to improve care transitions including medication reconciliation prior to discharge and communication with the primary care physician within 24 hours of discharge. Further description of the MACE service is included in the online supplement.

The usual care group included patients admitted to the general medical unit. Of note, the usual care team included an internal medicine attending, not a geriatrician, and did not have a clinical nurse specialist. In addition, usual care includes a unit-based social worker rather than a team-based social worker. All other aspects of care, including number of hospital floors or units, co-management with internal medicine housestaff, were similar for both groups of patients.

Study Design and Inclusion

Our study sample included patients admitted to the MACE service or general medical service, age 75 years and older, who were currently receiving primary care from a physician that was a member of the hospital faculty. We made this inclusion criterion because the vast majority of MACE service patients received primary care affiliated with the hospital and we wanted a comparable control sample. Proxy respondents were contacted if the patient had a history of dementia, had delirium determined using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) during eligibility verification,14 or did not score 4 or more on a 6-item cognitive screen with 3-item orientation and 3-item recall. We excluded patients admitted to any non-medicine unit or specialty service, including surgery, telemetry and respiratory care, because the MACE service does not manage patients on these units, as well as patients transferred from an outside hospital. Patients were contacted within 24-48 hours after admission to the MACE service or inpatient medical services.

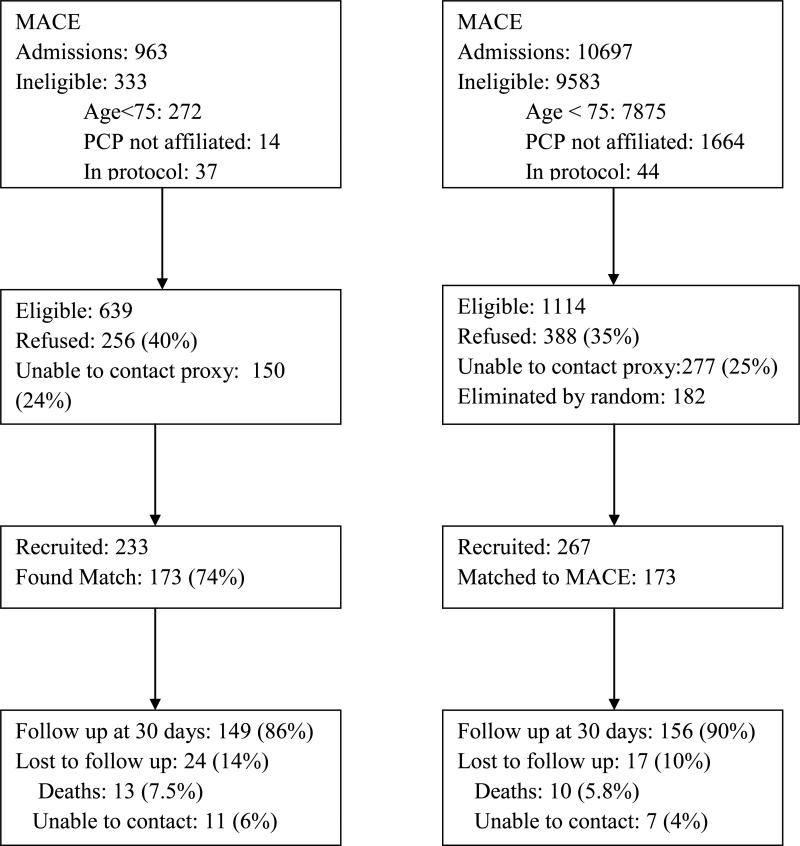

For this prospective, matched cohort study, all eligible and consenting patients admitted to the MACE service were enrolled to establish a pool of patients for prospective matching. Eligible and consenting control patients were enrolled from the general medical service (usual care) if they were matched with as yet unmatched enrolled patients from the MACE service using the following 4 characteristics: age within 5 years, ability to ambulate independently, primary admitting diagnosis categorized by body system, and admission within 180 days of one another. Usual care patients who met inclusion criteria but had no current matching patients from the MACE service were enrolled to a pool of unmatched usual care patients. If there were over 10 patients in the unmatched usual care pool, a computer-generated random number was used to select 50% of the eligible patients to be enrolled. Study flow is shown in Figure.

FIGURE.

Study Flow Diagram

Data Collection and Measures

Data were obtained by interviews on admission to the hospital and at 15 and 30 days post discharge and by medical record review by a clinician investigator who was not blinded to treatment assignment as medical records clearly indicated whether a patient was managed by the MACE service. The primary outcome measure was rehospitalization at 30 days after hospital discharge obtained through telephone interview. Other outcome measures included rehospitalization at 15 days after hospital discharge and self-reported hospital-based acute care utilization at 30 days, a composite that included hospitalizations, observation unit stays, and emergency room visits. Incidence of adverse events during incident hospitalization was collected through medical record review, which included catheter-associated urinary tract infection (UTI), falls, and restraint use. Catheter-associated UTIs were defined by the incidence of UTI in a patient who had an indwelling urinary catheter in the 48 hours prior to the onset of UTI. In addition, incidence of pressure ulcer during hospitalization was obtained through self report at 15 days after discharge.

Functional status at 30 days post discharge was assessed using the Functional Independence Measure-Motor (FIM-MOTOR) subscale15-17 and the Older Americans Resource Scale for Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (OARS-IADL).18 Patient satisfaction was measured using the 3-item Care Transition Measure (CTM-3)19 and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey (HCAHPS),20,21 which have been validated for hospitalized older adults to measure patient assessment of the quality of care transitions and satisfaction during hospitalization. Overall health-related quality of life was assessed using the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global 10-item instrument,22 which is a standardized, validated measurement for reliable measurement of patient-reported health status; EQ-5D score, a standardized measurement of health status developed by the EuroQol Group, was calculated from the PROMIS instrument.23

Other Covariates

Other covariates collected at baseline included age, sex, race, marital status, education level, insurance status, self-reported income, whether the patient lived alone and whether he or she had paid help prior to admission. Patient's history of chronic conditions was obtained from inpatient chart review in the medical record on admission and chronic conditions were summarized using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).24,25 Delirium on admission was assessed using CAM, a validated tool for screening for delirium.14 Severity of patient illness was measured using the physiological measure of a modified Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scale26 without the Glascow Coma Scale. Functional status at baseline prior to hospital admission was obtained from patient interview using the FIM-MOTOR scale. Number of outpatient medications prior to hospitalization was assessed through inpatient chart review. Number of previous hospitalizations in the year prior was assessed by chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics and outcome measures were compared between patients admitted to the MACE service and to usual care using McNemar's test, Stuart-Maxwell test and paired t-tests to account for matched cohort design. Next, we performed conditional logistic regression analysis for categorical outcomes, taking into account the matched-pair cohort design. We also performed fixed effect linear regression for continuous outcomes to obtain point estimates with multivariate adjustment to account for matching. 27 We included covariates in our multivariable models parsimoniously based on whether they were different between the groups and additionally included other important covariates anticipated to have a strong effect on the outcomes. Additional details on inclusion of covariates and sensitivity analyses are included in the online supplement. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1.

RESULTS

Our study procedures yielded a matching cohort of 173 patients in each group, drawing from a pool of 233 patients from the MACE service and 267 patients from usual care (Figure). Baseline characteristics of patients from the MACE service who matched to usual care patients were not substantially different from those who did not match except those who did not match were older (mean age 88.9, SD=7.0). All subsequent analyses were carried out on the matched cohort.

Patients managed by the MACE service had a mean age of 85.2 (Standard deviation [SD] 5.3), 76.3% were female, and 55.5% were white, which was well matched to the usual care group with a mean age of 84.7 (SD 5.4), 72.8% were female, and 48.0% were white (Table 1). Patients managed by the MACE service and usual care were equally likely to be Medicaid beneficiaries (34.7-36.4%). Only 31.8% were able to ambulate independently at baseline in both groups. Patients managed by the MACE service were slightly more ill on admission when compared to usual care group (Mean APACHE score of 10.0 (SD=3.5) vs. 9.1 (SD=2.8); p=0.004), had a higher prevalence of dementia (45.1% vs. 34.1%; p=0.03) and delirium on admission (22.5% vs. 10.4%; p=0.001), and were prescribed a higher number of medications at baseline (n=10.0 (SD=4.0) vs. n=8.0 (SD=4.0); p<0.001). A total of 149 (86.1%) patients from the MACE service and 156 (90.2%) patients from usual care completed 30-day follow-up. Baseline characteristics of patients who did not complete 30-day follow-up were not different from those who completed follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of matched patients admitted to Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) service and usual care (UC)

| MACE (n=173) | UC (n=173) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ± SD | 85.2 ± 5.3 | 84.7 ± 5.4 | 0.04 |

| Female Sex (%) | 76.3 | 72.8 | 0.45 |

| Race (%) | 0.07 | ||

| White | 55.5 | 48.0 | |

| Black | 20.2 | 17.9 | |

| Hispanic | 18.5 | 31.2 | |

| Other | 5.8 | 2.9 | |

| Marital status | 0.72 | ||

| Married (%) | 20.8 | 23.7 | |

| Widowed | 54.3 | 52.0 | |

| Other (single, divorced) | 25.9 | 24.3 | |

| Lives Alone (%) | 49.7 | 48.6 | 0.83 |

| Proportion with paid help at home (%) | 73.4 | 69.9 | 0.49 |

| Highest Education (%) | 0.58 | ||

| Less than High School | 27.2 | 33.5 | |

| High school Graduate | 22.0 | 19.7 | |

| Above High school | 49.1 | 44.5 | |

| Refused | 1.7 | 2.3 | |

| Income under 25K (%) | 42.2 | 44.5 | 0.89 |

| Medicaid beneficiary (%) | 36.4 | 34.7 | 0.74 |

| Ambulatory at baseline (%) | 31.8 | 31.8 | 1.0 |

| Function Independence Measure (FIM-Motor score) at baseline | 61.9 ± 23.1 | 60.2 ± 26.6 | 0.38 |

| OARS-IADL score (0- 14) | 6.2 ± 4.0 | 6.7 ± 4.6 | 0.25 |

| APACHE II | 10.0 ± 3.5 | 9.1 ± 2.8 | 0.004 |

| Number of medications | 10.0 ± 4.0 | 8.0 ± 4.0 | <0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity index (mean ± SD) | 2.4 ± 1.9 | 2.4 ± 1.9 | 0.76 |

| Number of prior hospitalizations (mean ± SD) | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 0.35 |

| Dementia (%) | 45.1 | 34.1 | 0.03 |

| Delirium on admission (%) | 22.5 | 10.4 | 0.001 |

| Common primary diagnoses on admission (%)* | |||

| Acute mental status change | 10.4 | 11.6 | |

| Syncope | 9.2 | 9.2 | |

| Pneumonia | 10.4 | 9.8 | |

| COPD/ asthma | 6.9 | 7.5 | |

| Abdominal pain/ Nausea/ Vomiting/ Diarrhea | 13.2 | 13.9 | |

| GI bleeding | 5.2 | 4.0 | |

| Falls/ Fractures | 12.7 | 13.9 | |

See online supplement for complete list of primary diagnoses.

Readmission

Among patients managed by the MACE service, 15.4% were readmitted within 30 days of discharge, compared with 22.4% of usual care patients (OR=0.67, 95% Confidence interval [CI], 0.35-1.25). After multivariable adjustment, there was no difference between the two groups on readmission risk at 30 days (adjusted odds ratio [OR]=0.91, 95% CI, 0.39- 2.10; p=0.83) (Table 3). Rates of acute care utilization, which combine visits to emergency departments and readmissions at 30 days, were also not different (20.8% versus 25.6%; OR=0.77, 95% CI, 0.36-1.64; p=0.50).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios of outcomes of patients admitted to Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) service using usual care (UC) group as reference

| Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 day hospital readmission | 0.91 | 0.39, 2.10 | 0.83 |

| 15 day hospital readmission | 0.59 | 0.14, 2.46 | 0.47 |

| 30 day hospital readmission or emergency room use | 0.77 | 0.36, 1.64 | 0.50 |

| 15 day hospital readmission or emergency room use | 0.68 | 0.20, 2.36 | 0.54 |

| Adverse events | 0.11 | 0.01, 0.88 | 0.04 |

All analyses were adjusted for age, white race, female, FIM score at baseline, APACHE score on admission, history of dementia and delirium on admission and number of medications above 10; for outcomes of hospital readmission, the analyses were additionally adjusted for number of previous hospitalization in the prior year and discharge location.

Adverse events

The incidence of adverse events in the hospital was lower among patients managed by the MACE service—9.5% had adverse events, including falls, pressure ulcers, catheter associated UTIs, or restraint use, whereas 17.0% had adverse events among the usual care group (p=0.02). After multivariable adjustment, incidence of any adverse events remained less likely among patients managed by the MACE service (adjusted OR= 0.11, 95% CI, 0.01-0.88; p=0.04).

Length of stay (LOS) and discharge location

Mean LOS among patients managed by the MACE service was 4.6 days (SD=3.3), which was shorter than the mean LOS among usual care patients (6.8 days (SD=7.6); p=0.001)) (Table 2). After multivariable adjustment, mean LOS was 0.8 days shorter among patients managed by the MACE service when compared to usual care patients (95% CI, 0.7-0.9; p=0.001). Discharge location among MACE and usual care patients was similar—approximately 25% of MACE patients were discharged to skilled nursing facility when compared with 22% of usual care group, although among those who were discharged home, MACE service patients were more likely to receive services at home including skilled nursing and chore services after discharge (82% vs. 69%; p=0.01).

Table 2.

Outcomes of patients admitted to Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) service and usual care (UC)

| MACE (n=173) | UC (n=173) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital readmission rate at 30 days | 15.4% | 22.4% | 0.21 |

| Hospital readmission rate at 15 days | 11.2% | 15.0% | 0.24 |

| Hospital readmission or ER visit at 30 days | 20.8% | 25.6% | 0.37 |

| Hospital readmission or ER visit at 15 days | 16.1% | 18.3% | 0.29 |

| Adverse events including: | 9.5% | 17.0% | 0.02† |

| Catheter associated urinary tract infection | 1.7% | 4.6% | |

| Restraint use | 0.6% | 2.9% | |

| Falls | 1.2% | 3.5% | |

| New decubitis ulcers | 8.7% | 10.9% | |

| Duration with indwelling foley catheter (days) | 0.8 ± 2.4 | 1.5 ± 5.8 | 0.13 |

| Length of stay ± SD | 4.6 ± 3.3 | 6.8 ± 7.6 | 0.001† |

| 30 day mortality | 7.5% | 5.8% | 0.51 |

| Discharge Location | 0.06 | ||

| Home with services | 59.0% | 52.6% | |

| Home without services | 9.8% | 22.5% | |

| SNF acute rehab | 4.6% | 3.5% | |

| SNF longterm care | 2.3% | 3.5% | |

| SNF subacute rehab | 17.9% | 15.0% | |

| hospice | 1.2% | 1.2% | |

| Function Independence Measure (FIM-Motor) | 60.9 ± 21.1 | 56.5 ± 27.0 | 0.24* |

| OARS- IADL score | 5.2 ± 3.6 | 5.9 ± 4.4 | 0.98^ |

| Care Transition Measure Score (CTM-3) | 72.5 ± 19.1 | 64.9 ± 16.5 | 0.01† |

| HCAHPS (as reported in hospital report cards)~ | |||

| Nursing Top Box (%) | 70.3 | 60.0 | |

| Doctor Top Box (%) | 81.4 | 78.2 | |

| Help top Box (%) | 38.0 | 39.0 | |

| Pain control top box (%) | 47.2 | 51.3 | |

| Medication communication top box (%) | 47.3 | 30.8 | |

| Discharge top box (%) | 68.9 | 53.3 | |

| Overall hospital rating top box (%) | 51.9 | 47.5 | |

| Satisfaction top box (%) | 50.0 | 44.1 | |

| Recommend hospital top box (%) | 72.9 | 72.5 | |

| Individual HCAHPS items (top) (%) | |||

| Explain new med | 68.3 | 48.2 | 0.37 |

| Talk about help you need after leaving hosp | 92.2 | 67.6 | 0.005 |

| Promis Tool (Physical) | 14.3 | 14.1 | 0.22 |

| Promis Tool (Mental) | 13.5 | 13.4 | 0.91 |

| EQ-5D (calculated) | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.58 |

| Overall health (Promis) | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.47 |

| Social Roles (Promis) | 4.3 | 3.9 | 0.36 |

adjusted for age, white race, female sex, APACHE score, FIM-Motor at baseline, history of dementia, and delirium on admission and number of medications

adjusted for age, white race, female sex, APACHE score, OARS-IADL score at baseline, history of dementia, and delirium on admission and number of medications

See online supplement for description of HCAHPs and definition of “top box”

p< 0.05

Functional status

Functional status in performing basic activities of daily living, measured using the FIM-Motor scale, at 30 days after discharge was 60.9 (SD=21.1) among patients under MACE service and 56.5 (SD=27.0) among usual care group (Table 2). The difference in FIM score between the two groups after multivariable adjustment was 2.3 points (95% CI, -1.6-6.1; p=0.24), which was not statistically significant. Ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living using the OARS scale was also not different between the two groups after multivariable adjustment (Coefficient 0.01, 95% CI, -0.54-0.56; p=0.98).

Patient satisfaction and health status

Patients under MACE service were more likely to report that they talked about the help they would need after discharge when compared with usual care (92.2% vs. 67.6%, p=0.005) (Table 2). Taken as a whole, patient satisfaction, measured using HCAHPS, was not substantially different between MACE and usual care. However, satisfaction measured using the CTM-3 was 7.4 points (95% CI, 2.9-11.9) higher among MACE patients than usual care (p=0.001) after multivariable adjustment.

Overall health status measured using the PROMIS tool at 30 days was not different among patients under MACE service and usual care, nor were the EQ-5D scores.

DISCUSSION

In this single site study of a redesigned ACE program, we found that the MACE service was associated with better outcomes in several important areas when compared with usual care and was not associated with worse outcomes, although readmission rates at 30 days and other measured outcomes did not differ significantly between the two groups. Of note, the MACE service was associated with lower rates of adverse events, shorter lengths of stay, and improved satisfaction on transitions of care. These findings suggest that providing inpatient care through a MACE service may be associated with better outcomes for this vulnerable older adult population.

The potential benefits of receiving care on a MACE service are likely multifactorial—as the service was built using an interdisciplinary approach, with a focus on multiple components including avoiding hazards of hospitalization, improving care coordination, and providing patient and caregiver education. Higher rate of use of home services among MACE patients at discharge may potentially mediate reduction in length of stay observed among patients under MACE care. Considering that few hospitals have dedicated units or floors for the care of older adults and the ACE unit model has had limited dissemination nationally, the MACE model may be a viable alternative, because it can be seamlessly integrated in a hospital's work flow without the requirement of a dedicated unit. The only new role that requires staffing is the nurse coordinator, as the social worker and geriatrics physician are obtained from reallocating existing resources.11 This cost may be offset by improved patient outcomes, including the reduction in length of stay and adverse event rates, the latter of which may lead to better reimbursement as payment is increasingly linked to outcomes. Further studies are needed to compare the effects and implementation barriers between MACE and other types of inpatient geriatric model such as consultative models. Of note, MACE was established as an inpatient care model integrated with an outpatient geriatric practice, which was a patient-centered medical home, and is now part of an accountable care organization (ACO). MACE may be a valuable component program of an ACO as more health care organizations adopt this model.

Although prior studies on physical ACE units demonstrated that functional status at hospital discharge could be improved through ACE unit care, the effect was not long lasting.28 This is consistent with our results, which showed little benefit associated with MACE care in patient functioning at 30 days after discharge.

A main limitation of the study is due to its observational design and its potential bias because patients under MACE service were also receiving care at a geriatrician-based primary care practice. Although we have taken steps to reduce potential imbalances between the comparison groups by using a prospective matching method, it is possible that some of the effects associated with the MACE service may be related to its association with a geriatric primary care practice. Through our matching strategy, we were able to establish a control group that differed from MACE service patients on a few measured variables. However, these differences suggested that MACE service patients were sicker than the comparison group, which may imply that our results may underestimate the effectiveness of receiving care from the MACE service. An additional limitation is that for the outcome of hospital adverse events, the review of medical record was by a single investigator unable to be blinded to group assignment. This is a single center study in an urban tertiary medical center; further studies in other settings are needed to demonstrate its generalizability.

In conclusion, the MACE service is a readily adaptable model of inpatient care which may be associated with better outcomes for hospitalized older adults. As hospital systems devise ways to improve care delivery and the quality of care for older adults, the MACE service model should be considered.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Data access and responsibility: All authors had full access to all the data in the study. Dr. Hung takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding/support and role of the sponsor: Support for this project was provided by the John A. Hartford Center of Excellence and in part by the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Mount Sinai School of Medicine (P30-AG028741). The sponsor played no role in the design of the study, analysis or interpretation of findings, or drafting the manuscript and did not review or approve the manuscript prior to submission. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented. Dr. Ross is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG032886) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Drs. Hung, Ross, and Siu were responsible for the conception and design of this work. Dr. Hung drafted the manuscript, conducted the statistical analysis, and was responsible for acquisition of data. Drs. Ross and Siu provided supervision. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Ross is a member of a scientific advisory board for FAIR Health, Inc. and receives grant funding from Medtronic, Inc. to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing, from the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop and maintain performance measures that are used for public reporting, and from the Pew Charitable Trusts to examine regulatory issues at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

REFERENCES

- 1.Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Feb 1;118(3):219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [August 13, 2012];Serious reportable events. 2012 http://www.qualityforum.org/Topics/SREs/Serious_Reportable_Events.aspx.

- 3.Bakker FC, Robben SH, Olde Rikkert MG. Effects of hospital-wide interventions to improve care for frail older inpatients: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011 Aug;20(8):680–691. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.047183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baztan JJ, Suarez-Garcia FM, Lopez-Arrieta J, Rodriguez-Manas L, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Effectiveness of acute geriatric units on functional decline, living at home, and case fatality among older patients admitted to hospital for acute medical disorders: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009;338:b50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: a randomized controlled trial of Acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000 Dec;48(12):1572–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landefeld CS, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, Fortinsky RH, Kowal J. A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995 May 18;332(20):1338–1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer RM, Landefeld CS, Kresevic D, Kowal J. A medical unit for the acute care of the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994 May;42(5):545–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb04978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.KG S, BW D, KM M, editors. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. . Vol Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Rockville (MD): 2001. Geriatric Evaluation and Management Units for Hospitalized Patients. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes DE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. Acute care for elders units produced shorter hospital stays at lower cost while maintaining patients’ functional status. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012 Jun;31(6):1227–1236. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayadevappa R, Bloom BS, Raziano DB, Lavizzo-Mourey R. Dissemination and characteristics of acute care for elders (ACE) units in the United States. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19(1):220–227. doi: 10.1017/s0266462303000205. Winter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farber JI, Korc-Grodzicki B, Du Q, Leipzig RM, Siu AL. Operational and quality outcomes of a mobile acute care for the elderly service. J Hosp Med. 2011 Jul-Aug;6(6):358–363. doi: 10.1002/jhm.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charpentier PA, Bogardus ST, Inouye SK. An algorithm for prospective individual matching in a non-randomized clinical trial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Nov;54(11):1166–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Jr., Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999 Mar 4;340(9):669–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990 Dec 15;113(12):941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang WC, Chan C, Slaughter SE, Cartwright D. Evaluating the FONE FIM: Part II. Concurrent validity & influencing factors. J Outcome Meas. 1997;1(4):259–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang WC, Slaughter S, Cartwright D, Chan C. Evaluating the FONE FIM: Part I. Construct validity. J Outcome Meas. 1997;1(3):192–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollak N, Rheault W, Stoecker JL. Reliability and validity of the FIM for persons aged 80 years and above from a multilevel continuing care retirement community. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996 Oct;77(10):1056–1061. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doble SE, Fisher AG. The dimensionality and validity of the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale. J Outcome Meas. 1998;2(1):4–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Eilertsen TB, Thiare JN, Kramer AM. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:e02. doi: 10.5334/ijic.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NQF endorses HCAHPS patient perception survey. Healthcare Benchmarks Qual Improv. 2005 Jul;12(7):82–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 30;359(18):1921–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0804116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009 Sep;18(7):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Revicki DA, Kawata AK, Harnam N, Chen WH, Hays RD, Cella D. Predicting EuroQol (EQ-5D) scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items and domain item banks in a United States sample. Qual Life Res. 2009 Aug;18(6):783–791. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9489-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994 Nov;47(11):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985 Oct;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCulloch CE, Neuhaus JM. Generalized linear mixed models. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Kresevic DM, et al. Improving functional outcomes in older patients: lessons from an acute care for elders unit. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998 Feb;24(2):63–76. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.