Abstract

The objective was to study the effect of colpocleisis on pelvic support, symptoms, and quality of life and report-associated morbidity and postoperative satisfaction. Women undergoing colpocleisis for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) were recruited at six centers. Baseline measures included physical examination, responses to the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory, and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. Three and 12 months after surgery we repeated baseline measures. Of 152 patients with mean age 79 (±6) years, 132 (87%) completed 1 year follow-up. Three and 12 months after surgery, 90/110 (82%) and 75/103 (73%) patients following up had POP stage ≤1. All pelvic symptom scores and related bother significantly improved at 3 and 12 months, and 125 (95%) patients said they were either ‘very satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’ with the outcome of their surgery. Colpocleisis was effective in resolving prolapse and pelvic symptoms and was associated with high patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Pelvic organ prolapse, Urinary incontinence, Pelvic floor disorders, Colpocleisis, Quality of life, Surgical outcomes

Introduction

By the year 2030, adults over 65 years of age will account for approximately 20% of the US population [1], and an estimated 80% of those have at least one chronic medical condition [2]. Since the prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse increases with age, gynecologists will be required to care for an increasing number of older women seeking treatment for prolapse. In older women who do not seek to maintain vaginal coital function, colpocleisis offers high anatomic success rates [3]. Potential benefits compared to a reconstructive approach include decreased operative time, blood loss, and recuperative time. Few studies have systematically assessed the impact of colpocleisis on bladder and bowel symptoms using validated questionnaires, especially over a clinically significant time period. Lacking this information, clinicians are somewhat limited in their ability to fully counsel patients considering colpocleisis for prolapse.

Our objectives were to determine the effect of colpocleisis on pelvic organ support, pelvic symptoms, quality of life, and patient satisfaction, to describe the morbidity associated with colpocleisis, to report patients’ assessment of sexual function and body image, and to describe outcomes with and without concomitant incontinence surgery during clinical care of patients undergoing colpocleisis.

Materials and methods

This cohort study enrolled patients planning to undergo colpocleisis and prospectively followed them for 1 year after surgery. The study was performed at six sites of the National Institute Health-funded Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Each site obtained Institutional Review Board approval, and all participants provided informed consent to participate. Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they had decided to undergo colpocleisis for advanced pelvic organ prolapse (pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) stage III–IV) and were able to comprehend and complete study forms and procedures.

At baseline, we recorded demographic measures, severity of prolapse as assessed using the POP-Q system [4], postvoid residual urine volume measured by catheterization within 10 min of spontaneous void, and results of any preoperative objective testing for stress incontinence. We neither standardized nor required preoperative testing for incontinence as there was no data with which to base a recommendation of this type of preoperative clinical testing. Similarly, we did not dictate management of any incontinence that was present. When performed, acceptable forms of objective testing included standing cough stress test with 300 mL instilled into the bladder, or multichannel urodynamic testing performed according to each site’s standard protocol, with the prolapse reduced using ring forceps in either case. We did not prescribe preoperative uterine evaluation when the surgical plan was to leave the uterus in situ. Postoperative catheter management was determined by local practices.

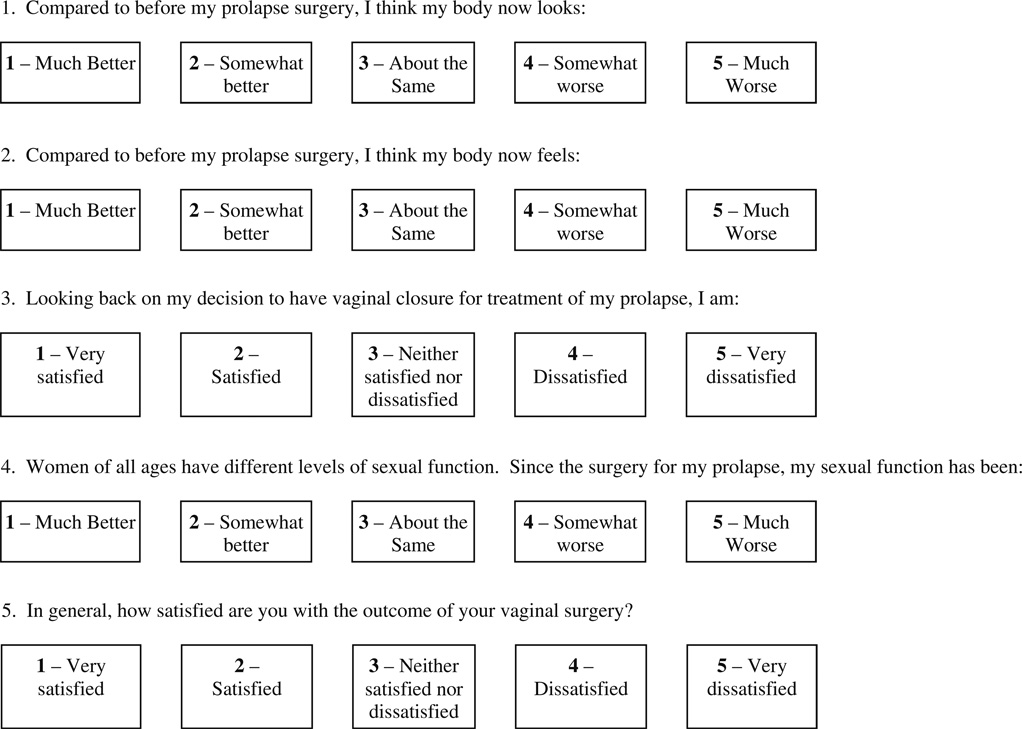

Study coordinators administered the following symptom and quality of life questionnaires in person: Short Form-36 (SF-36) generic health-related quality of life questionnaire, Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI; including the Urinary Distress Inventory (UDI), Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI) and Colorectal Anal Distress Inventory (CRADI)), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ; including the Urinary Impact Questionnaire (UIQ), the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ), and the Colorectal Anal Impact Questionnaire (CRAIQ)), and a nonvalidated Body Image and Satisfaction Questionnaire (see “Appendix”). The Short Portable Mental Status Examination was administered at baseline to subjects aged 75 and older and to younger subjects who appeared to have cognitive dysfunction during the interview; subjects with moderate to severe intellectual dysfunction were to be excluded.

Colpocleisis and any additional procedures were performed according to surgeon preference. The surgeon reported the type of colpocleisis performed, concomitant procedure(s) performed including levator plication and/or perineorrhaphy, operating time, intraoperative blood loss, and complications. Surgeons all preserved the anterior vaginal epithelium caudad to the urethrovesical junction, leaving the distal 3 to 4 cm of the vagina patent. Total colpocleisis was defined as removal of all vaginal epithelium cephalad to the urethrovesical junction to the level of the vaginal cuff, both anteriorly and posteriorly. Partial colpocleisis was defined as partial removal of the vaginal epithelium cephalad to the urethrovesical junction anteriorly and posteriorly creating a longitudinal vaginal septum with bilateral vaginal epithelium tunnels (e.g., LeFort colpocleisis).

We assessed vaginal topography 3 months and 1 year after surgery, including measurement of total vaginal length (TVL), length of genital hiatus (GH), and perineal body (PB) while straining. The total vaginal length was measured in the midline. Additionally, we recorded the position of the most dependent point of the vaginal apex, anterior and posterior vagina with respect to the leading skin edge of the vaginal introitus while straining, and staged this based on the POPQ staging system [4]. Voiding status was recorded as either voiding without difficulty, needing intermittent catheterization, or needing indwelling catheter.

Three months and 1 year after surgery, the SF-36, PFDI, and PFIQ were readministered along with questions relating to a global assessment of satisfaction and of body image (see “Appendix”). If subjects were unable to attend any postoperative clinic visit, study questionnaire measures were collected by telephone. In the event that surgery was necessary for recurrent prolapse, stress incontinence, or urinary retention, all postoperative measures were obtained before reoperation or retreatment.

Stress incontinence symptoms were considered present if the participant responded “yes” to any of three items in the “Stress” UDI subscale (leak with cough, sneeze, or laugh; leak with exercise; leak with bend over or lift). Urge urinary symptoms were considered present if a “yes” response was given to any of five items in the “Irritative” UDI subscale (urgency, urge incontinence, frequency, nocturia, and enuresis). Symptoms were considered bothersome if the subject chose “moderately” or “quite a bit” of bother.

To test whether PFDI and PFIQ subscales improved after surgery, we used two-sample paired signed rank tests. McNemar's test was used to compare proportions of subjects with incontinence symptoms before and after surgery.

Results

A total of 152 patients were recruited, whose demographic information is summarized in Tables 1 and 2. After enrollment, no subject was excluded due to cognitive impairment. Patients were predominantly Caucasian (92%), with age range 65–94 years. Partial colpocleisis was performed in 88 (58%) and total colpocleisis in 64 (42%) patients. Additional procedures performed at the time of colpocleisis included: hysterectomy (8%), levator myorrhaphy (68%), and perineorrhaphy (96%). Seventy-one (47%) patients underwent concomitant incontinence procedures: polypropylene midurethral sling (n=55), xenograft suburethral sling (n=2), suburethral plication (n=13), and periurethral collagen injection (n=1).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients at baseline (n=152)

| Mean±SD | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 79.3±5.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9±5.6 |

BMI Body mass index

Table 2.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients at baseline (n=152)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Black | 12 (8%) |

| White | 140 (92%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 3 (2%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or living as married | 65 (43%) |

| Other | 87 (57%) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 32 (21%) |

| Completed high school or equivalent | 68 (45%) |

| Some college or higher | 52 (34%) |

| Prior surgery for incontinence | 20 (13%) |

| Prior hysterectomy | 92 (60%) |

| Prior surgery for prolapse | 31 (20%) |

| POP-Q stage | |

| Stage III | 91 (62%) |

| Stage IV | 55 (38%) |

POP-Q Pelvic organ prolapse quantification

The mean (±standard deviation (SD)) blood loss for the entire cohort was 119±97 mL and the operative time was 112±51 min. The estimated blood loss in the total colpocleisis group was significantly greater than in the partial colpocleisis group, 149 (±127) mL vs. 90 (±56) mL, respectively (p=0.002), even after excluding patients who underwent concurrent hysterectomy. Operative time in the total colpocleisis group was significantly longer than in the partial colpocleisis group (121±41 vs. 94±47 min; p=0.0011). Intraoperative complications were uncommon, with one patient each having cystotomy, ureteric kinking, and urethral injury during the surgery. There were no reported rectal injuries. Mean hospital stay was 1.6±0.7 days, and mean duration of catheterization was 1.4±0.9 days.

As detailed in Table 3, adverse events were commonly reported during the year following surgery. Urogenital adverse events were most common, the majority representing urinary tract infections. Serious adverse events requiring prolonged hospitalization or subsequent surgery included two patients who were diagnosed with cancer during or after their index hospitalization. One patient had endometrial cancer diagnosed from the endometrial curettings obtained at the time of colpocleisis and subsequently underwent total abdominal hysterectomy and staging with final diagnosis of stage IC grade I papillary endometrial adenocarcinoma. Another had a noninvasive low-grade transitional cell bladder cancer diagnosed during cystoscopy at the time of colpocleisis. Five months after colpocleisis, one patient died of sepsis and congestive heart failure apparently unrelated to the surgical experience. There was no difference in serious adverse events between the total and partial colpocleisis groups.

Table 3.

Adverse events during the first postoperative year classified by event type or organ system affected; unless otherwise indicated, each event represents a single patient

| During initial hospitalization |

After initial hospital discharge and before 3 month follow-up visit |

Between 3 month and 12 month follow- up visit |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Urogenital | 5 | 69 (68 patients) | 58 |

| Pulmonary | 11b | 2 | 0 |

| GI | 14 | 5c | 2 |

| Skin/wound | 2 | 9 (7 patients) | 1 |

| Infection | 5 | 4 | 0 |

| Cardiovasculara | 6 | 1 | 4 (3 patients) |

| Neurologic | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Neoplasm | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Endocrine and allergy | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other (hyponatremia) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Includes emergency room visits for chest pain, regardless of eventual attribution

Includes one patient who developed pulmonary edema requiring intubation and ventilation

Includes one patient who developed new-onset rectal prolapse after colpocleisis and underwent subsequent surgical repair

One hundred ten and 103 patients had objective POP-Q assessment 3 and 12 months after surgery, respectively. Those who did not have objective POP-Q assessment were similar at baseline to those who did have objective assessment. One hundred and seven (97%) patients at 3 months and 96 (93%) at 12 months had POP stage 2 or better (Table 4) with 90 (82%) at 3 months and 75 (73%) having POP stage 0 or 1. POP outcomes were similar in patients with and without concomitant levator myorrhaphy and when those undergoing total colpocleisis were compared to those undergoing partial colpocleisis. As expected, the median postoperative TVL and GH measurements decreased and PB measurements increased (p<0.0001). Also indicated in Table 4, stress incontinence symptoms were present in almost half of the patients 1 year after surgery but were bothersome in only 14%. Bothersome urge incontinence symptoms were present in 15% of patients 1 year after surgery. All PFDI and PFIQ subscale scores improved after surgery (see Table 5) with improvements attained by 3 months and maintained until 12 months after surgery (p<0.0001).

Table 4.

POP-Q measurements and urinary incontinence symptoms at baseline, 3 and 12 months after surgery

| Variable | Baseline | 3 months postoperation |

12 months postoperation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomic measures (data available for146 patients at baseline, 110 at 3 months, and 103 12 months after surgery) | Most distal vaginal point (leading edge) | |||

| ≤1 cm inside hymen | 0 (0%) | 90/110 (82%) | 75/103 (73%) | |

| ≤1 cm beyond hymen | 0 (0%) | 107/110 (97%) | 96/103 (93%) | |

| >1 cm beyond hymen | 146/146 (100%) | 3/110 (3%) | 7/103 (7%) | |

| TVL (cm) | 9 (8, 10) | 3 (3, 4) | 3 (2.5, 4) | |

| GH (cm) | 6 (4, 7) | 2 (1.5, 3) | 2 (1.5, 3) | |

| PB (cm) | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (4, 5.5) | 4 (4, 5) | |

| Urinary symptoms (denominator varies by time point) | Stress incontinence symptoms present | 105/140 (75%) | 63/136 (46%) | 62/131 (47%) |

| Bother with stress incontinence present | 75/139 (54%) | 26/135 (19%) | 18/130 (14%) | |

| UUI/OAB symptoms present | 91/140 (65%) | 43/136 (32%) | 50/131 (38%) | |

| Bother with UUI/OAB present | 58/140 (41%) | 16/136 (12%) | 20/131 (15%) |

Data presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range)

POP-Q Pelvic organ prolapse quantification, TVL total vaginal length, GH genital hiatus, PB perineal body

Table 5.

Questionnaire scores related to generic health-related quality of life, pelvic symptoms, and life impact at baseline, 3 months and 1 year after surgery

| Timing of assessment N |

Baseline 152 |

3 months after surgery 141 |

12 months after surgery 132 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF36 physical | 42±9 | 43.2±16.3a | 44.3±15.7c |

| SF36 mental | 51±10 | 51.7±18.6 | 55.5±19.0a |

| PFDI—POPDI | 113±61 | 25.35±31.5b | 26.03±30.65b |

| PFDI—UDI | 97±56 | 26.19±29.02b | 26.68±32.32b |

| PFDI—CRADI | 71±63 | 37.17±48.17b | 41.24±50.75b |

| PFIQ—POPIQ | 45±64 | 6.36±20.62b | 6.98±22.19b |

| PFIQ—UIQ | 71±67 | 23.90±36.65b | 23.65±39.85b |

| PFIQ—CRAIQ | 34±58 | 12.81±32.94b | 16.15±44.44b |

Data presented as mean±SD. SF36 physical—range 0–100, higher score implies better quality of life. SF36 mental—range 0–100, higher score implies better quality of life. OPDI subscale of the PFDI—range 0–300, lower scores indicate less bother. UDI subscale of the PFDI—range 0–300, lower scores indicate less bother. CRADI subscale of the PFDI—range 0–400, lower scores indicate less bother. POPIQ subscale of the PFIQ—range 0–400, lower scores indicate less life impact. UIQ subscale of the PFIQ—range 0–400, lower scores indicate less life impact. CRAIQ subscale of the PFIQ—range 0–400, lower scores indicate less life impact

PFDI Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory, POPDI Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory, UDI Urinary Distress Inventory, CRADI Colorectal Anal Distress Inventory, PFIQ Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire, POPIQ Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire, UIQ Urinary Impact Questionnaire, CRAIQ Colorectal Anal Impact Questionnaire, SF36 physical physical component of the SF36, SF36 mental mental component of the SF36

SF36 subscore significantly improved compared to baseline (p<0.005)

Three-month and 1-year subscores significantly improved compared to baseline (p<0.0001)

SF36 subscore significantly improved compared to baseline (p=0.015)

Before surgery, 75% (105/140) of subjects had “any” complaint of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) where 54% of subjects (75/139) had complaints of “bothersome” SUI (Table 4). Preoperative objective stress testing was performed in 141 (92%) patients, with objective evidence of stress urinary incontinence demonstrated in 40 of 70 (57%) with bothersome stress incontinence and in 28 of 58 (48%) without bothersome stress incontinence symptoms.

The prevalence of new onset vs. persistent bothersome stress incontinence symptoms after surgery are presented in Tables 6. Bothersome stress incontinence symptoms 1 year after surgery were reported by 13% (8/62) of women who had an incontinence procedure and 14% (8/57) of women who did not have an incontinence procedure.

Table 6.

Presence of bothersome SUI symptoms after surgery in women with and without preoperative bothersome SUI based on whether or not incontinence surgery was performed at the time of colpocleisis

| Bothersome SUI 3 months after surgery | Bothersome SUI 1 year after surgery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

| Prevalence of bothersome SUI 3 months and 1 year after colpocleisis in women who had preoperative bothersome SUI: of the 75/139 (55%) patients who had preoperative bothersome SUI, data was available for 68 and 64 patients at 3 months (n=68) and 1 year (n=64), respectively | ||||||||

| Underwent concomitant incontinence surgery | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 (21%) | 31 (79%) | 6 (17%) | 30 (83%) | ||||

| No | 8 (28%) | 21 (72%) | 6 (21%) | 22 (79%) | ||||

| Prevalence of bothersome SUI 3 months and 1 year after colpocleisis in women who did not have preoperative bothersome SUI: of the 62/139 (45%) patients who did not have preoperative bothersome SUI, data was available for 59 and 55 patients at 3 months (n=59) and 1 year (n=55), respectively | ||||||||

| Underwent concomitant incontinence surgery | ||||||||

| Yes | 6 (24%) | 19 (76%) | 2 (8%) | 24 (92%) | ||||

| No | 4 (12%) | 30 (88%) | 2 (7%) | 27 (93%) | ||||

Results included for 127 women with complete pre- and postoperative SUI data. Bothersome SUI symptoms were considered present if a “yes” response was given to any of three items in the “Stress” Urinary Distress Inventory subscale (leak with cough, sneeze, or laugh; exercise; and bend over or lift) and for any of these the patient chose ‘moderately’ or ‘quite a bit’ of bother. Seventy-one out of 152 women underwent incontinence surgery. One hundred and thirty-seven patients had bothersome SUI available at baseline

No patients had surgery for postoperative voiding difficulty, but one patient required use of an indwelling catheter because of urinary retention at 3 months after surgery. Four patients underwent further treatment for prolapse or incontinence during the year after colpocleisis: one underwent repeat colpocleisis and three underwent suburethral sling procedure for stress incontinence.

One year after surgery, looking back on their decision to have vaginal closure for treatment of their prolapse, 78 (59%) patients said they were ‘very satisfied’, 47 (35%) were ‘satisfied’, five (4%) ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, one (1%) ‘dissatisfied’, and one (1%) ‘very dissatisfied’. At 1 year, 87 (66%) said they were ‘very satisfied with the outcome of their vaginal surgery’, 37 (28%) were ‘satisfied’, five (4%) were ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, one (1%) were ‘dissatisfied’, and two (2%) were ‘very dissatisfied’. One year after surgery, only two (2%) of women indicated that compared to before their surgery; they thought their body now looked ‘worse’ while 49 (37%) indicated their body looked ‘the same’ and 80 (61%) indicated their body looked ‘better.’ Similarly, only three (2%) noted a worsening in the way their boy now felt with 121 (92%) indicating their bodies felt ‘better.’ Finally, just two (3%) stated that since the surgery, their sexual function was ‘worse’, with 69 (87%) indicating it was the same and eight (10%) indicated sexual function was ‘better’.

Discussion

This multisite prospective cohort study utilized validated subjective and objective outcome measures to describe outcomes in a cohort of older women choosing colpocleisis for treatment of prolapse. In line with other case series, we found that colpocleisis has a high prolapse repair success rate at 1 year. We found little change in anatomic outcome between the 3 month and 1 year postoperative visits, and just one subject underwent a repeat colpocleisis. This is consistent with clinical experience and with a recent literature review [3] that reported success rates between 91% and 100% with follow-up intervals ranging from 2 weeks to 15 years. Paralleling the anatomic outcome, there was also a significant improvement in prolapse symptoms and life impact as measured by condition-specific symptom and life impact scales completed 3 months and 1 year after surgery.

We found that intraoperative procedure-specific complications were uncommon but that general postsurgical adverse events were relatively common in this group of older women. Since reporting of complications in women undergoing colpocleisis has been variable in quality, our ability to compare our experience with other cohorts is limited but broadly appears to be similar. Complications related to gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and cardiovascular organ systems were most common during the initial hospitalization and occurred at levels similar to those previously reported [3]. Importantly, we found that urogenital events, the majority of which were urinary tract infections, occurred in 45% of patients between discharge and 3 months after surgery and in 38% of subjects between 3 months and 1 year after surgery. Since urosepsis can be an important source of morbidity in the older woman, we believe this result raises but does not answer the question of whether prophylactic antibiotics should be considered for a time after urogenital surgery in similar older patients.

Lower urinary tract symptoms and their life impact markedly improved by the 3 month assessment, an improvement that was maintained at the 1 year follow-up. Only 14% of patients expressed bother with stress incontinence symptoms at 1 year, compared to 54% at baseline. Similarly, only 15% described bother with urge symptoms at 1 year, compared to 41% at baseline. These outcomes are in agreement with the significant decrease in UDI subscales (stress, irritative, and obstructive) previously reported in a retrospective cohort of 54 subjects [5]. Importantly, we were able to show improvement in both stress and urge urinary incontinence symptoms both in patients who did and did not have a concomitant incontinence procedure performed. We did not dictate the form of preoperative urinary tract evaluation and did not prescribe treatment when urinary incontinence was present. Therefore, our results do not add significantly to what is known about management of the lower urinary tract at the time of colpocleisis but do suggest that a randomized trial may be helpful in helping to define definitive management in this population of women undergoing obliterative surgery. In our cohort, similar rates of postoperative bothersome SUI occurred at 1 year in those who did and did not undergo concomitant incontinence procedures (13% and 14%, respectively); furthermore, rates of this outcome appeared similar in women who did and did not undergo incontinence surgery when preoperative bothersome SUI was present (17% and 21%, respectively) and absent (8% and 7%, respectively). Importantly, new-onset troublesome SUI was not common, whether or not an incontinence procedure was performed, being present at 1 year in just 4% of patients who had an incontinence procedure and in 3% of patients who did not. In contrast to what might be clinically expected in this older cohort, no patients required urethrolysis or sling excision for persistent voiding difficulty after surgery, although three patients required a subsequent sling surgery. While these results may be useful in counseling women planning colpocleisis about benefits and potential risks associated with concomitant incontinence surgery, we are unable to make firm conclusions about our findings, since the decision to perform an incontinence surgery was not standardized in this observational study.

We also explored issues related to sexual function, body image, and satisfaction after colpocleisis. There has been some concern that a procedure which significantly alters female anatomy and ability to have vaginal intercourse may adversely affect body image, cause regret about loss of vaginal function, and ultimately cause patient dissatisfaction [6, 7]. Barber et al. recently compared a cohort of older women undergoing obliterative procedures to a cohort undergoing reconstructive vaginal surgery for prolapse and found that women choosing an obliterative approach had similar improvements in quality of life without an increase in depression or alteration in body image [6]. Similarly, we found that 1 year after surgery, 94% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with their decision to have vaginal closure for management of their prolapse, the majority were similarly satisfied with the outcome of their surgery, and deterioration in sexual function was seldom reported.

Limitations of this study include the lack of a comparator group of similar women undergoing reconstructive surgery or nonsurgical treatment for prolapse. We also did not include geriatric-specific measures of functional status that may have been particularly revealing about perioperative effects of prolapse surgery. Lastly (as above), since this was an observational study, we did not standardize the objective preoperative and postoperative bladder evaluation and the decision whether to perform a concomitant incontinence procedure and we cannot make firm conclusions or recommendations regarding the management of this clinically difficult problem at this time.

As the number of older women seeking care for prolapse continues to increase, it is imperative that we are able to adequately counsel these patients with respect to risks and benefits of this surgical approach. Further studies addressing the best approach to the management of both overt and potential stress incontinence in the setting of colpocleisis are needed.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U01 HD41249, U10 HD41268, U10 HD41248, U10 HD41250, U10 HD41261, U10 HD41263, U10 HD41269, and U10 HD41267) and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K24 DK068389).

Appendix

Body image and satisfaction

We were interested in learning about how women feel after prolapse surgery. There are no right or wrong answers. We are just interested in learning about how you feel after your surgery. I will start with the first question:

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest None.

Contributor Information

M. P. FitzGerald, Email: Mfitzg8@lumc.edu, Division of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Loyola University Medical Center, 2160 South First Avenue, Bldg 103, Room 1004, Maywood, Il 60153, USA.

H. E. Richter, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA

C. S. Bradley, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA

W. Ye, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

A. C. Visco, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

G. W. Cundiff, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

H. M. Zyczynski, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

P. Fine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

A. M. Weber, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD, USA

for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD, USA.

References

- 1.US Census Bureau. U.S. interim projections by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. [Accessed October 24, 2007];2007 Available at http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The state of aging and health in America. [Accessed October 25, 2007];2007 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/aging.

- 3.Fitzgerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J. 2006;17(30):261–271. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheeler TL, Richter HE, Burgio KL, et al. Regret, satisfaction, and improvement: analysis of the impact of partial colpocleisis for the management of severe pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2067–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber MD, Amundsen CL, Paraiso MFR, et al. Quality of life after surgery for genital prolapse in elderly women: obliterative and reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2007;18:799–806. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0240-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jelovsek J, Barber MD. Advanced pelvic organ prolapse decreases body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1455–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]