Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is the foremost cause of morbidity and mortality in the Western world. Atherosclerosis followed by thrombosis (atherothrombosis) is the pathological process underlying most myocardial, cerebral, and peripheral vascular events. Atherothrombosis is a complex and heterogeneous inflammatory process that involves interactions between many cell types (including vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, macrophages, and platelets) and processes (including migration, proliferation, and activation). Despite a wealth of knowledge from many recent studies using knockout mouse and human genetic studies (GWAS and candidate approach) identifying genes and proteins directly involved in these processes, traditional cardiovascular risk factors (hyperlipidemia, hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, sex, and age) remain the most useful predictor of disease. Eicosanoids (20 carbon polyunsaturated fatty acid derivatives of arachidonic acid and other essential fatty acids) are emerging as important regulators of cardiovascular disease processes. Drugs indirectly modulating these signals, including COX-1/COX-2 inhibitors, have proven to play major roles in the atherothrombotic process. However, the complexity of their roles and regulation by opposing eicosanoid signaling, have contributed to the lack of therapies directed at the eicosanoid receptors themselves. This is likely to change, as our understanding of the structure, signaling, and function of the eicosanoid receptors improves. Indeed, a major advance is emerging from the characterization of dysfunctional naturally occurring mutations of the eicosanoid receptors. In light of the proven and continuing importance of risk factors, we have elected to focus on the relationship between eicosanoids and cardiovascular risk factors.

Keywords: Eicosanoids, Atherothrombosis, Prostaglandins, Prostanoids, Platelets, Hypertension, Hyperlipidemia, Oxidative stress, Diabetes mellitus

Atherothrombosis

Atherothrombosis, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally [1], is a complex inflammatory disease of the arterial wall [2] in which a sclerotic plaque of lipid and fibrous tissue is deposited over time, often leading to rupture and thrombus formation. Such vascular lesions create a depot for circulating lipids, prompting an immune response, and developing feedback amplification of inflammatory mediators further enhancing material deposition [3]. As the sclerotic plaque remains relatively innocuous while stable, the onset of a thrombotic event is highly unpredictable in both occurrence and severity [4]. Initiated by fatty streak deposition with oxidized low-density lipoprotein [5, 6], the atherosclerotic lesion development is driven by inflammation [7] and is pathologically enhanced by dyslipidemia [8, 9]. Thrombosis results from platelet interaction with the plaque [10]. In dyslipidemic mice, lesion-prone vasculature shows enhanced expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules, VCAM-1 and P-selectin, prior to atherosclerotic plaque deposition [11]. Cell adhesion markers provide attachment points for circulating platelets and leukocytes [12, 13]. Platelets are ubiquitous throughout lesion initiation, plaque growth, and thrombosis [14–19]. The resulting thrombosis can manifest as unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or sudden death [20–22]. Platelet activation is the primary target for anti-thrombotic therapy [10], with clopidogrel inhibition of adenosine receptors and aspirin inhibition of thromboxane generation being most effective [23]. Relationships between eicosanoids and cardiovascular disease risk factors have been long recognized [24]. The following review focuses on the biology of eicosanoid signaling, and their roles in modifying and regulating critical processes involved with the major risk factors associated with heart disease.

Eicosanoids

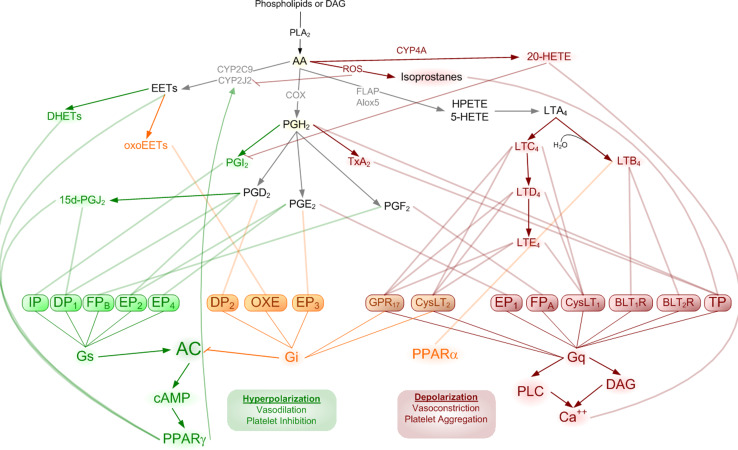

Eicosanoids are oxidative metabolites of arachidonic acid involved in highly concerted and largely self-regulated cellular signaling. Liberation from arachidonic acid (AA) from lipid membrane, by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) initiates a signaling cascade with diverse downstream second messenger amplification steps promoting multiple potentially contradictory cellular behaviors. Culminating effects are largely dependent upon the availability of specific enzymes and the receptors with which the various members of this ligand family can interact (Table 1). The formation and activity of these ligand families has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [25–27]. Briefly, AA is immediately oxidized into one of three primary pathways via cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, or cytochrome P450, generating upstream substrates for the prostaglandins, leukotrienes, or epoxyeicosanoids, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Eicosanoid receptors involved in atherothrombosis

| Receptor | Eicosanoid ligand | Primary effectors | Vascular expression | Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP (PTGIR) | Prostacyclin (PGI2) | Gs | Endothelia, VSMC, platelets | Vasodilation, anti-aggregation |

| TP (TBXA2R) | Thromboxane (TxA2), isoprostanes, PGH2 | Gq/G11 | Platelets, VSMC, macrophage | Vasoconstriction, aggregation |

| EP1 (PTGER1) | PGE2 | Gq | VSMC, endothelia | Vasoconstriction, aggregation |

| EP2 (PTGER2) | PGE2, OxPAPC | Gs | Platelets, VSMC | Vasodilation, anti-aggregation |

| EP3 (PTGER3) | PGE2 | Gi | Platelets, VSMC, endothelia | Vasoconstriction, aggregation |

| EP4 (PTGER4) | PGE2 | Gs | Platelets, VSMC, endothelia | Vasodilation, anti-aggregation |

| DP1 (PTGDR) | PGD2, PGJ2 | Gs | Endothelia, VSMC, platelets, | Vasodilation, anti-aggregation |

| CRTh2 (DP2, GPR44) | PGD2, 11-dehydro-TxB2, OxPAPC | Gi/Go | Endothelia | Vasoconstriction |

| FPa (PTGFR) | PGF2a | Gq/G11 | Endothelia, VSMC | Vasoconstriction |

| FPb | PGF2a | Gs | Endothelia, VSMC | Vasodilation |

| CysLT1R (Cystl1) | LTC4, LTD4, LTE4 | Gq | Endothelia, leukocytes, platelets | Vasoconstriction, aggregation |

| CysLT2R | LTC4, LTD4, LTE4 | Gq/G11 | Endothelia, platelets | Vasoconstriction, aggregation |

| GPR17 (UDP/CysLT) | LTC4, LTD4, UDP | Gi, Gq/G11 | Endothelia | Vasoconstriction |

| BLT1R (Ltb4r) | LTB4 | Gq/G11 | Leukocytes, endothelia, macrophage | Vasodilation |

| BLT2R (Ltb4r2) | LTB4 | Gq/G11 | Macrophage, endothelia | |

| OXE (GPR170) | 5-oxo-ETE | Gi | Leukocytes, macrophage |

Fig. 1.

Arachidonic acid is oxidized by various means to produce downstream signaling mediators. The complexity of these pathways results from differential processing of each of the major signaling classes (prostaglandins, epoxyeicosanoids, and leukotrienes) producing ligands with overlapping and counteracting receptor interactions. These interactions predominantly converge on two opposing intracellular signals resulting in cellular hyperpolarization (via cAMP) or cellular depolarization (via intracellular calcium flux)

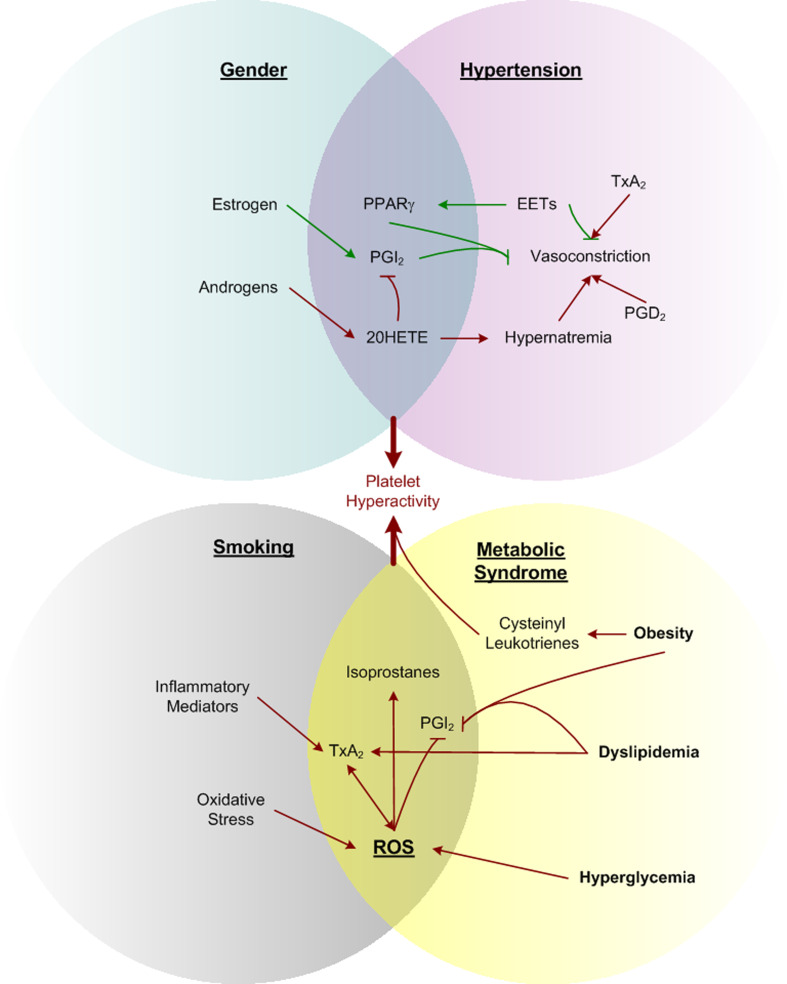

In addition to the direct agonism of these ligands at their cognate receptors, the resulting signals also involve promiscuous mechanisms including agonism and antagonism at receptors for other eicosanoids, competition for synthesis at processing enzymes, and transactivation of non-canonical pathways. Further complexity arises when precursor substrates can be delivered to nearby cells for transcellular processing [28] and the convergence of signaling pathways on shared second messengers with competing cellular responses determined by the composite effect of multiple ligands. It is important to consider these intricacies when facing the myriad of seemingly contradictory effects and incomplete phenotypes (when pathway components are knocked out). Unraveling such an orchestration is beyond the scope of this review and is currently being intensely studied. Rather, we will focus on how specific portions of these intricate pathways influence known cardiovascular risk factors, where large gaps of knowledge remain in tying together the cardiovascular influence of eicosanoid signals (Fig. 2), and where considerable opportunities in deciphering eicosanoid biology remain ripe for active research (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

A subset of eicosanoids provides convergent stimuli from dominant risk factors. Sex-specific hormones influence hypertension through differential effects on the production of cardioprotective prostacyclin and related mediators. Smoking and metabolic syndrome both promote reactive oxygen species. A common downstream effect of each mechanism includes contributing to platelet hyperactivity. Inflammatory cytokines released from platelets exaggerates these effects through positive feedback signaling

Table 2.

Challenges and opportunities in eicosanoid receptor pharmacology

| Challenge | Effected receptor | Phenomenon and implications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative splicing | TP | ||

| TP | Opposite AC coupling, different R60L sensitivity, desensitization, regulation by NO and PGI2, timing of ERK activation | [293–297] | |

| EP3 | [298] | ||

| FP | Altered drug response | [299] | |

| Heterodimerization | IP/TP | Form new iPE2III binding site | [300] |

| IP/TP | Co-regulation via endocytosis | [301] | |

| IP/TP | Promote TxA2 cAMP response | [302] | |

| TPα/TPβ | Enhance isoprostane signal | [303] | |

| CysLT1/CysLT2 | Altered internalization | [304] | |

| CysLT1/GPR17 | Negative regulator | [305, 306] | |

| Genetic variants | IP: R212C | Accelerated atherothrombosis through dominant-negative influence | [87, 307, 308] |

| IP: R212H | pH sensitivity | [309] | |

| IP: R77C, R215C | Impaired cAMP production | [310] | |

| IP: M113T, L104R, R279C | Misfolding, impaired binding | [311] | |

| TP: R60L, D304N | Severe bleeding, abolished ligand binding | [312] | |

| CysLT1: G300S | Asthma, atopy | [313] | |

| CysLT2: A601G | Reduced ligand affinity, atopy | [314, 315] |

Prostaglandins (PG) are products of AA where cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1) or cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) adds two oxygen to form the five-member ring structure of prostaglandin G2 (PGG2), and spontaneously sheds an oxygen to give prostaglandin H2 (PGH2), which can then be converted to any of the prostaglandin signaling molecules by one of the specific synthases. Isoprostanes are prostaglandin-like eicosanoids formed by peroxidation by free radicals and reactive oxygen species [29], primarily of AA, but also form from other lipid and fatty acid precursors [30]. Predominant effects of PG and isoprostanes in the context of cardiovascular hemostasis include effects on vasculature, platelets, and leukocytes. Prostanoid receptors mediate hemostatic responses including vasoconstriction, predominantly through thromboxane A2 (TxA2), with similar effects from TxB2 and PGF2α, effects which are countered by vasodilation via PGE2, PGI2, LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4 [31]. Many of the same components regulate inflammatory responses including platelet activation (TxA2) and inhibition (PGD2, PGI2), as well as leukocyte induction (TxA2, LTB4) and inhibition (PGD2, PGE2).

Leukotrienes (LT) are formed in a more linear fashion through a lipoxygenase-generated intermediate, hydroperoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid (HPETE), which gives rise to leukotriene A4, via 5-HETE. The addition of water to LTA4 gives LTB4, whereas addition of cysteine-based glutathione, by glutathione-S-transferase, produces leukotriene LTC4, metabolized to cysteine-containing LTD4 and LTE4. These cysteinyl leukotrienes signal through two specific receptors CysLT1 and CysLT2 which, though more well studied in the context of asthma (contractile and proinflammatory) in the cardiovascular system, LTC4 and LTD4 are hypotensive [32]. Leukotriene receptors are expressed on platelets [33], but cysteinyl leukotrienes are also importantly known to directly interact with P2Y12 receptors [34], which are the target receptors of clopidogrel.

Epoxyeicosanoids (EETs) are products of cytochrome P450 epoxygenation of AA, and provide a major anti-inflammatory signal [35, 36]. The formation and activity of EETs on endothelial dysfunction has been recently reviewed [37]. Whereas cytochrome epoxygenases (predominantly CYP family 2C) [38] synthesize epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in endothelia and promote vasodilation, ω-hydroxylase gives rise to hydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (HETEs) promoting vasoconstriction [38]. Interestingly, when acting on linoleic acid rather than AA, Cyp2C generates reactive oxygen species [39, 40].

Risk factors

Significant reductions in coronary heart disease over recent years stem from improved risk factor profiles [41]. The Framingham Heart Study is among the most influential of cardiovascular clinical studies, providing comprehensive health evaluations for over 10,000 individuals across three generations [42]. The study was used to develop a multivariate prediction model of coronary heart disease risk, identifying the major risk factors of hypertension, cholesterol, smoking, diabetes mellitus, age, sex, and race. Identification of these risk factors has guided clinical mitigation of coronary disease progression with considerable success. Although collectively addressing patient risk factors has decreased the overall prevalence of cardiovascular events [43], individually addressing hypertension or glucose imbalances in diabetic patients has been less effective than anticipated at improving outcomes [44–48]. Together, these observations indicate that although each risk factor can individually contribute to pathology, the complexity and severity of cardiovascular disease stems from the multifaceted interactions between these complicated factors.

Recognition of the complexity of risk factor contributions leads to two specific approaches for managing cardiovascular events. The current approach is to combine therapies directed at distinct risk factors. Multiple points of intervention have the advantages of providing tight control of each specific response. However, there remain inherent limitations and potential dangers with a combined therapy approach including drug–drug interactions and side-effects from multiple drugs [49, 50]. An alternative strategy would be to identify a common denominator in the mechanism of multiple risk factors for focused intervention. To employ either approach effectively requires improved understanding of the underlying pathophysiology and detailed investigation into the underlying pathways through which these risk factors intersect. Interestingly, despite the eicosanoids playing key roles in the regulation of many of these cardiovascular risk factors, no eicosanoid-based drug is currently being used both in the treatment and prevention of atherothrombosis. This is in part due to the complex and ubiquitous nature of their actions, leading to many potential side-effects. Understanding tissue-specific regulation of eicosanoids, the corresponding signaling pathway-specific actions, and the conformational changes required for such signaling may ultimately lead to development of tissue/receptor/pathway-selective drugs required to precisely activate or inactivate a tissue-specific function.

Gender

There is a clear difference in the influence of risk factor categories on coronary heart disease in males and females [51]. The risk contribution of HDL cholesterol, for instance, is stronger in females than in males [51], whereas cigarette use shows much higher risk contribution for males [52]. Postmenopausal increases in androgens [53] are associated with increased risk for cardiovascular events in females [54] and support the protective role of estrogens relative to androgens. Such a protective effect has been demonstrated by estrogen through stimulation of prostacyclin synthesis [55]. This may arise, at least in part, from a well-defined estrogen response element in the promoter of the human prostacyclin receptor [56]. Therapeutic treatment with aspirin (a low-dose COX-1 inhibitor reducing platelet thromboxane production) shows a similar divergence, providing protective effects against strokes in women and against myocardial events in men, but not vice versa [57]. Increased thromboxane synthesis with decreased prostacyclin synthesis is associated with atherosclerotic lesion burden in female ApoE−/− mice, relative to both female wild-type and male ApoE−/− mice, despite reduced cholesterol levels [58]. Similarly, PGE2, prostacyclin, and thromboxane production are higher in female mouse macrophages than in male [59].

Production of the cytochrome P450 eicosanoid 20-HETE correlated with increased blood pressure and sodium retention in male rats maintained on a high-fat diet relative to those fed a control diet [60]. Female rats, however, did not induce 20-HETE on a high-fat diet unless they were treated with exogenous androgens. Increased 20-HETE production is associated with oxidative stress [61] and endothelial dysfunction [62]. Specific inhibition of 20-HETE reduces postmenopausal hypertension [63]. Interestingly, however, 20-HETE inhibits COX-2 up-regulation [64], and 20-HETE and other vasoconstrictors are preferentially formed with COX-2 inhibition [65].

Increasing blood pressure increases 20-HETE production by both neutrophils and platelets [66]. 20-HETE contributes to vascular smooth muscle depolarization by inhibiting potassium-calcium channels [67] and promoting calcium influx via L-type calcium channels [68]. Vasoconstriction is mediated by calcium flux-induced depolarization of vascular smooth muscle [69, 70]. Interestingly, the androgen-driven elevation in blood pressure related to 20-HETE production is directly tied to sodium retention [60]. In general, the evidence suggests that hormonal regulation of eicosanoids contributes to both hypertensive response in males and premenopausal cardioprotection in females. There remains much to be explored on differential regulation of eicosanoids in cardiovascular disease and risk factors.

Hypertension

The most consistent cardiovascular risk factor across genders is hypertension [71, 72], contributing to age-related coronary heart disease risk more than any other single risk factor [73]. Lipidomic profiling of hypertensive versus normotensive individuals indicates reduced membrane AA content [74], which might suggest increased lipid mobilization [75], though numerous other mechanisms may be responsible for the disparity. In coordination with many other vasoactive agents, systemic blood pressure is largely maintained by balancing the vasodilatory effects of vascular wall-generated PGI2 and nitric oxide with the vasoconstrictive effects of platelet-derived TxA2 [76].

Though blood pressure is maintained through the combined efforts of numerous mechanisms beyond the scope of this review [77–81], baseline hypertension is largely influenced by vascular wall biology, where the common mechanistic pathway responsible for vasoconstriction of the vasculature (increased peripheral resistance) is vascular smooth muscle cell depolarization causing contraction. The depolarization is caused by intracellular calcium flux, which is primarily opposed by cyclic AMP formation, blocking calcium influx [82]. PGI2, PGD2, and PGE2 can also promote vasodilation via Gs stimulation of adenylyl cyclase (AC), generating cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), hyperpolarizing VSMC. In the opposing direction, TxA2 stimulates intracellular calcium release, promoting VSMC constriction via membrane depolarization.

Prostacyclin and thromboxane

Prostacyclin is a potent vasodilator with critical involvement in vascular disease (anti-atherothrombosis, cardioprotective), which has recently been reviewed [83]. Despite having a robust pro-inflammatory influence in the context of rheumatoid arthritis, prostacyclin (PGI2) serves anti-inflammatory roles in vasculature, inhibiting atherosclerotic formation [84]. The predominant effects of prostacyclin are a result of limiting the effect of thromboxane [85]. In accordance with the overwhelming vasodilatory role of prostacyclin, mice with predominant COX-1 prostanoid formation (analogous to selective COX-2 inhibition) develop systolic hypertension from high salt (reversible with prostacyclin receptor agonist) despite increased formation of all other major prostanoids [86]. Indeed, a dysfunctional prostacyclin receptor arising from a human genetic variant (R212C) was associated with an increased prevalence of hypertension [87]. This variant also accelerates progression of atherothrombotic disease in humans [87].

Prostaglandin E2

In addition to the roles of PGI2 and TxA2, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2, also known as dinoprostone) also demonstrates clear hemodynamic influence. Reducing PGE2 synthesis by genetic deletion of microsomal PGE synthase-1 (mPGES-1) causes severe hypertension and impaired sodium excretion [88] through PGE2 effects on aquaporin [89]. This response is attributed to the EP2 and EP4 receptor subtypes which, like the prostacyclin receptor (IP), are coupled to Gs [90].

However, the role of PGE2 in cardiovascular disease is multifaceted [91], largely due to the presence of four cell-surface receptors (EP1–4), with different secondary messengers often leading to opposing downstream effects. EP1 receptor deficiency, for instance, decreases resting systolic blood pressure [92] with compensatory increases in pulse rate and renin activity in males, through reduced angiotensin II hypertension [93]. The primary effector for EP1 is Gq, promoting intracellular calcium release [90]. The primary EP3 secondary messenger is Gi, decreasing cellular cAMP formation. The opposing stimulus, cAMP formation via AC activation, is carried out by EP2 and EP4 coupling to Gs (the same effector as IP). The ability of PGE2 to stimulate opposing pathways complicates defining a clear role of PGE2 in hypertension.

EETs

The cytochrome P450 (Cyp)-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) utilize alternative mechanisms to influence vascular tone. EETs induce vasodilatation through hyperpolarization [94] of vascular smooth muscle cells [95] via activation of large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels [96], further contributing to the salt-sensitivity of angiotensin-dependent hypertension [97]. Vascular benefits of EETs extend from reducing platelet aggregation [98] and adhesion [99], to reducing the endothelial inflammatory response [35]. Some EET isomers inhibit cyclooxygenase, reducing thromboxane formation; however, all EETs reduce platelet aggregation [98]. EETs also interfere with platelet adhesion to endothelia by hyperpolarizing platelets [100]. Angiotensin II, a prothrombotic vasoconstrictor, impairs Cyp2C synthesis of EETs [101, 102] while increasing EET catabolism to lower activity dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETs) [103] by soluble epoxide hydrolase [94, 104] causing a loss in systemic EET availability.

The EETs directly stimulate PPARγ [105] and competitively antagonize the thromboxane A2 receptor [106]. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), a putatively cardioprotective omega-3-series fatty acid [107, 108], induces endothelial EET formation by Cyp2J2 via PPARγ, while inhibiting the exaggerated VSMC growth observed in spontaneously hypertensive rats [109]. EPA also reduces platelet activation in both CAD patients [110] and healthy subjects [111].

Cytochrome P450 epoxygenases 2C9 and 2J2 are directly inhibited by H2O2, reducing EET production under oxidative conditions [112] such as ROS. Interestingly, nitric oxide produces a similar inhibition of EET formation [113]. As oxidative stress can cause hypertension [114] and hypertension promotes oxidative stress [115], it is not surprising that lifestyle recommendations for reducing the risk of high blood pressure and cardiovascular events, each reduce oxidative stress, including smoking cessation, weight loss, exercise, reducing alcohol consumption, consuming a healthy diet, and reducing stress.

Smoking and oxidative stress

The very nature of eicosanoids as oxidative metabolites of ubiquitous membrane components implies a direct relationship to oxidative stress. The relationship between smoking, oxidative stress, and inflammation is well established, but complex. Smoking increases risk of coronary heart disease alone [116], but also greatly increases risk in combination with other risk factors [43, 117]. Cigarette smoke is a complex mixture of molecules, each with a distinct pharmacological response. Nevertheless, many direct influences of habitual smoking promoting heart disease are modulated by eicosanoids: hypertension [88, 89], tachycardia [118–121], reduced cardiac output [122], cholesterol accumulation [123], vessel damage [124], and promotion of clot formation [125].

Cigarette smoke contains multiple agents contributing directly to inflammation. Lipid-soluble smoke particles consisting of DMSO-soluble particles (DSP), nicotine, and lipopolysaccharides, upregulate G protein-coupled receptors for potent contractile agents, endothelin and thromboxane, [126] which contribute to endothelial dysfunction [127]. In addition to upregulating contractile receptors, LPS exposure simultaneously increases activation of inflammatory and contractile thromboxane and angiotensin I receptors while inhibiting anti-inflammatory and dilatory prostacyclin and acetylcholine receptors [128].

Isoprostane production

Smoking increases oxidative stress markers malondialdehyde (MDA) [129] and isoprostanes [130] through free-radical catalyzed peroxidation of AA and AA metabolites [131, 132], as well as inflammatory markers C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-6 [129]. Elevated circulating levels of homocysteine are also associated with smoking [133] and constitute a strong risk for endothelial dysfunction [134] and associated cardiovascular events [133]. Homocysteine is generated through methionine metabolism, with elevated levels most commonly associated with vitamin B deficiencies [135]. Elevated homocysteine increases thromboxane synthesis [136] and isoprostane formation [137], enhancing platelet activity [138]. Nevertheless, attempts to lower homocysteine levels have failed to reduce cardiovascular events [139, 140], despite significant reductions in homocysteine levels.

With numerous potential avenues leading from smoke to reactive oxygen species [129, 141], the resulting effect is an increased systemic inflammatory state. Direct effects of increased oxidation on eicosanoids include vascular and platelet alterations [142]. In addition to stimulating inflammatory response through the thromboxane A2 receptor [143], isoprostanes contribute to angiotensin II-induced vasoconstriction [144]. F2-isoprostanes are elevated in both chronic and acute smoking, accompanied by decreased plasma arachidonate. A role for oxidative stress-derived isoprostanes [145] in activation of the thromboxane receptor may explain some cases of observed aspirin resistance [146]. The thromboxane receptor is critical to these events and is targeted by isoprostanes. This suggests that TP receptor antagonists may be protective, but these are not yet widely used. Specific antagonists of the thromboxane A2 receptor are in development. The PERFORM study of stroke patients demonstrated no benefit over aspirin treatment [147], but lacked a sufficiently severe population (e.g., aspirin-resistant or diabetic patients) to observe the anticipated benefits of such an approach [148]. An additional potential drawback to thromboxane receptor inhibition is that combined inhibition of COX-2 and TP can destabilize plaques [149]. This could interfere with the therapeutic utility of such an approach, since smaller and less stable plaques are more likely to precipitate acute clinical events as they lack protective collateral formation [150].

HETEs in oxidative stress

Generally, the detrimental effects of smoking are best summarized as oxidative damage-promoting chronic inflammation. In addition, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, visceral obesity, and hyperhomocysteinemia all contribute to inflammatory signals promoting formation of reactive oxygen species. In addition to the direct increase in formation of 8-iso-PGF2α from oxidative stress, HETE levels are also elevated with chronic smoking, which show no further increase with acute smoking [151]. Additional eicosanoid influence from oxidative damage includes reduction of beneficial EETs [112], and formation of 12-HETE by 12-LOX oxidation of AA [152], smoking cessation among heavy smokers (at least 20 cigarettes/day) improves platelet function by increasing sensitivity to PGE1, and resulting in decreased mean platelet volume (less basal activation) without altering the total number of platelets [153]. The influence of smoking modifies production of each eicosanoid class and occurs predominantly through an increased inflammatory state caused by the combined effects of inhaled mediators and oxidative stress.

Metabolic syndrome

Individuals frequently exhibit multiple metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease. This suggests that these risk factors may arise from a common underlying etiology, but the molecular basis for the clustering of risk factors is not yet understood. “Metabolic syndrome” is defined as having three or more of these risk factors, which include central obesity, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, hypertension, excessive blood clotting, and dyslipidemia. While patients diagnosed with metabolic syndrome are not treated differently—the individual risk factors are still addressed accordingly—this classification is important because it identifies a subset of patients at the greatest risk. The presence of metabolic syndrome corresponds to a doubling of cardiovascular disease risk, along with a fivefold increased risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus [154]. As measures and mechanisms can be distinguished between these risk factors, each is discussed separately; however, there is considerable overlap between their roles, as each is considered to support a proinflammatory state.

Diabetes mellitus

Whereas oxidative stress and hypertension have direct and obvious influences on the cardiovascular system, the linkage between glucose regulation and cardiovascular disease has been conceptually more challenging, though no less important. The insulin-resistance and associated glycemic dysregulation from type 2 diabetes mellitus doubles the risk of coronary heart disease [155] and related vascular complications, as well as increasing the risk of normotensive patients [156]. However, efforts to control glucose levels have proven much less effective than anticipated in decreasing cardiovascular events in diabetes [156–158], and aggressive glucose control therapy has at times been associated with worsening outcomes from severe hypoglycemic vascular events, likely due in some cases to off-target effects of specific medications [159, 160].

Platelet hyperactivity has been a recognized response to hyperglycemia for decades [161], and is responsible for numerous diabetic complications [162]. It is difficult to tease out differences from diabetic and oxidative contributions to atherothrombosis, as they are intimately related through the observation that hyperglycemia produces ROS [163]. Nevertheless, in a rat model of type 2 diabetes mellitus, the formation of an eicosanoid oxidative stress marker, 8-iso-PGF2α was decreased by anti-oxidant vitamin E or anti-diabetic PPAR agonist troglitazone [164]. Hyperglycemia from diabetes mellitus increases oxidative stress, enhancing lipid peroxidation [165]. Increased thromboxane synthesis and isoprostane production have been noted in type 2 diabetic patients [166, 167], and circulating levels of these eicosanoids can be reduced with intense glucose lowering [168]. These positive feedback signals result in persistent platelet activation in diabetic patients, marked by increased urinary 11-dehydro TxB2 in patients with DM, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension, and correlated with increased vascular events [168, 169]. A recent study revealed that high glucose increases both thromboxane synthesis and TP expression through an aldose reductase-dependent mechanism [167].

One particularly important and commonly measured isoprostane, 8-iso-PGF2α, is a peroxidation product of AA, and is increased in diabetic patients with levels correlating to both blood glucose and thromboxane metabolite levels [168]. Both thromboxane and isoprostane are effective activators of the thromboxane A2 receptor (TP), leading to recent interest in using TP antagonism as a therapeutic approach for diabetes [170]. However, there remain significant and unidentified differences in thromboxane and isoprostane signaling, as sCD40L release appears to be selective for thromboxane activation of platelets [171]. Further, antioxidant therapy with vitamin E reduced both isoprostane and thromboxane formation in diabetic patients [168], whereas aspirin has no influence on isoprostane formation. As both thromboxane and isoprostanes activate one of the critical positive feedback signals in platelet activation, the TP receptor is becoming recognized as a critical link between insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease [27, 167, 170].

Obesity

As with diabetes mellitus, obesity (often measured by body mass index, BMI) has been a long-recognized risk factor in cardiovascular disease [172], associated with dyslipidemia, oxidative stress, increased thromboxane production [173], and hyperactive platelets [174]. The inverse association of exercise habits with cardiovascular events [175] is often attributed to the resulting obesity. Interestingly, while moderate obesity is associated with atherosclerotic burden and increased thromboxane production, morbid obesity is often associated with reduced atherosclerotic burden and decreased thromboxane production. In cases of extreme obesity, higher BMI measures seem to confer a slight protective effect relative to moderate obesity, though still elevated relative to non-obese [176]. However, studies found that while hs-CRP and leptin levels increased with BMI, TxB2 was reduced in both lean subjects and insulin-sensitive morbidly obese patients [173]. Perhaps this sheds some light on the obesity paradox in which morbid obesity reduced risk relative to moderate obesity [177]. Insulin-resistant morbidly obese patients had higher elevated circulating inflammatory markers than those who were insulin sensitive [178]. Furthermore, they found increased ERK phosphorylation and NF-κB activation in biopsied visceral adipose tissues of the insulin-resistant group, consistent with the increased systemic inflammation, and responsible for downstream alterations in IRS-1 and Akt. These findings support the opinions of others who have long viewed insulin resistance as a condition of chronic inflammation [179]. More recently, an 11-year longitudinal study acknowledged that changes in patient fitness provide substantial long-term benefits in cardiovascular prognosis irrespective of BMI levels [180]. Acute exercise increases F2-isoprostane formation which is short-lived; however, chronic exercise leads to sustained decreases in isoprostane levels [181]. A similar pattern of inflammatory cytokine production with acute exercise and reduction with extended training has been reported [182]. Isoprostanes provide one convergence point between dyslipidemia, oxidative stress, and platelet hyperactivity.

Dyslipidemia

Hypercholesterolemia is known to enhance thromboxane A2 synthesis [183, 184]. Notably, atherosclerotic plaques in LDL receptor knockout mice on a high-fat diet have increased TxAS and TxA2 levels [185]. The LDL receptor is responsible for cellular uptake of cholesterol-rich low-density lipoprotein [186]. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels are a risk factor closely related to obesity. Oxidation of low-density lipoprotein generates platelet-stimulating lipid mediators including F2-isoprostane and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) [187]. While reduction of LDL cholesterol levels by statins has beneficial effects, LDL itself remains harmless until oxidized [188]. Oxidized LDL is a component in plaques, but the oxidation of LDL also releases isoprostanes [189]. Conversely, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) has protective effects relative to LDL, largely by promoting cholesterol efflux [190]. Interestingly, whereas isoprostanes are produced from oxidized LDL, HDL is the major lipoprotein carrier of plasma isoprostanes, reducing free isoprostane effects by providing means of both sequestering and inactivating isoprostanes [191]. Infusion of HDL has been shown to reduce atheroma volume in cardiac catheterization patients [192].

The omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA have been cautiously reported as having generally beneficial effects in cardiovascular disease [193], by shifting lipid metabolism to less inflammatory pathways, reducing blood pressure, and platelet activity. They similarly associate with decreases in the plasma oxidative stress marker, F2-isoprostanes [194]. Short-term treatment with DHA modifies the prostanoid synthesis profile of megakaryocytes [195], reducing pro-inflammatory AA derivative formation. However, simply changing the substrate lipid does not entirely avoid oxidative processing, and platelets treated with DHA possess both pro- and anti-oxidant activities [196]. Although generally favoring less inflammatory eicosanoids over their AA-derived counterparts, extended omega-3 fatty acid consumption can also increase vascular endothelial permeability induced by platelet-activating factor [197]. A detailed comparison of the specificities and potencies of 2-series AA-derived and 3-series EPA-derived prostaglandins indicates that EPA is an effective inhibitor of AA oxygenation by PGHS-1 and that 3-series derivatives had reduced efficacy and partial agonism at EP receptors, suggesting a number of possible signaling benefits of omega-3 supplementation. However, the same study also highlights important limitations: namely, that TP activation remains nearly identical, and that PGHS-2 preferentially metabolizes AA series compounds [198].

An important consideration in obesity research is the different characteristics across types of adipose tissue. Adipocytes are generally categorized as white adipose or brown adipose tissue, driven largely by mitochondrial content [199]. Large numbers of active mitochondria (with high iron content) cause some adipocytes to have a brown tint [200] and result in a highly metabolically active cell with many small thermogenic lipid-processing droplets, as opposed to the white adipocytes consisting primarily of a single large lipid droplet for long-term energy storage. The effect of lipid composition on adipocyte phenotype is not limited to pharmacological manipulation, but occurs endogenously as specific fatty acids are selectively mobilized from adipocyte tissue during lipolysis as a function of the chain length and degree of saturation [201], resulting in preferential mobilization of eicosanoid precursor forms for PGE2 and PGI, which potently influence adipocyte development [202] and lipolysis. Such findings suggest additional opportunities in seeking influence from omega-3/omega-6 lipid balance on adipocyte fate through altered eicosanoid production. This works both ways of course, with white adipocytes promoting PGE2-biased lipolysis [203], maintaining low cAMP levels relative to brown adipose tissue. Investigating the decision-making process behind fate determination in preadipocyte mesenchymal progenitors, Vegiopoulos et al. [204] identified COX-2 as a critical component in the induction of brown adipose tissue formation.

Over-expressing COX-2 shifts progenitor cells toward a brown adipose phenotype (with a high metabolic capacity measured by mitochondrial thermogenic genes (UCP1, CIDEA, CPT1B, DIO2). Use of the prostacyclin analog carbaprostacyclin has a similar effect, whereas COX-2 inhibition results in a nearly complete population of white adipose cell types. The same phenotypic shift, when driven by β-adrenergic activity, was also interrupted with COX-2 inhibition, suggesting that this effect was also mediated by eicosanoid production. Additionally, the β-adrenergic receptors, like the prostacyclin IP receptor, couple to Gs, stimulating AC to produce cyclic AMP. Cyclic AMP stimulates lipolysis [205], whereas cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, stimulated by intracellular calcium flux, hydrolyze cyclic AMP and terminate the signal. Compared to normal weight controls, obese individuals have higher PGE2 levels, formed predominantly by adipocyte phospholipase A2 (AdPLA) in white adipose tissue [206]. Removing AdPLA or selectively blocking EP3 receptors blocked increased PGE2 expression typically induced by a high-fat diet and prevented both weight gain and cAMP suppression.

Platelet hyperactivity and interactions with endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells

Many of the risk factors and associated eicosanoids modulate the activity of circulating platelets [207]. There are clear pathophysiological links between platelet alterations and gender [208, 209], hypertension [210–212], chronic smoking [213–215], diabetes [167, 216, 217], and obesity [218–220]. Platelet hyperactivity, in particular, is an effective predictor of a poor prognosis for patients with a recent myocardial infarction [221].

Thromboxane and prostacyclin

In the context of platelet activity, the most profound eicosanoid effects are observed with thromboxane and prostacyclin. Thromboxane stimulates platelet activation and aggregation through a self-perpetuating positive feedback loop via Gq stimulation of intracellular calcium release. Prostacyclin overrides this process, providing an anti-activation cAMP signal via Gs stimulation of AC. The platelet activation signal converges on intracellular calcium mobilization, largely through TP and related pathways exacerbate atherosclerosis [222]. Of many downstream effects, TP activation promotes an additional convergence point between dyslipidemia and platelet hyperactivity through CD40/CD40L stimulation [223]. This response is independent of aspirin [224], highlighting the overlapping integration of multiple activating pathways.

The role of thromboxane as a primary feedback pathway of platelet activation [225] is central to cardiovascular diseases and has been recently reviewed [226]. The TP receptor is activated and stabilized by ROS [227], and TxA2 ligand is similarly induced by hyperglycemia via ROS [167]. Furthermore, TP stimulation also increases production of ROS [228], revealing yet another level of thromboxane-positive feedback amplification. Acute glucose exposure reduces the ability of COX inhibitors to inhibit platelet aggregation regardless of the stimuli [229], reducing the effectiveness of aspirin and exaggerating platelet responses under hyperglycemic circumstances.

TP knockout mice on an apoE null background have reduced atherogenesis, whereas the IP receptor knockout mice develop accelerated atherogenesis [230]. These atherogenic effects include effects on smooth muscle cells, but also on platelet responses. Proliferative and migratory effects of thromboxane on smooth muscle cells are enhanced by platelet-released serotonin (5-HT) at sub-threshold concentrations [231], suggesting an important role for platelet thromboxane release in restenosis. Thromboxane may affect migration in other cell types as well. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from human adipose tissue become migratory and proliferative in response to thromboxane receptor agonism (with U46619) and show markers suggesting differentiation into smooth-muscle-like cells [232] via ERK and p38 MAPK. A similar pro-migratory effect of thromboxane receptor activity has been recognized in endothelia [233] where either COX-2 inhibition or TXA2 antagonism attenuated FGF-induced corneal angiogenesis, and TxA2 agonism reconstitutes the angiogenic response.

Prostaglandin E2

The effects of PGE2 on platelets are less profound and less specific, but no less important. As with hemostasis, the influence of PGE2 platelet signaling involves counteracting signaling. EP2 and EP4 provide a prostacyclin-like Gs/cAMP response, whereas EP1 elicits a pro-aggregatory thromboxane-like Gq/calcium response, with the additional complication of EP3-mediated Gi inhibition of AC. Owing to the presence of multiple receptor targets, PGE2 provides a modulating effect, shifting the balance between the pro-aggregatory Gq and calcium signal (via EP1) [234] and the anti-aggregatory Gs-cAMP signal (via EP2 and EP4) [235], tempered by an inhibitory influence on cAMP through Gi via EP3 [236]. The predominant effects on platelets are via the EP3 and EP4 receptors [234], though these alternative signaling pathways likely play integral roles in other tissues.

Despite a general observation of PGE2-inhibiting platelet aggregation [237], specific EP3 antagonism is often required to observe platelet aggregation. Interestingly, decreasing PGE2 formation via PGE2 synthase-1 decreases plaque burden [238], supporting an important, if unclear, role for PGE2. The platelet inhibitory effect occurs primarily through EP4, attenuating calcium release [239], though selective stimulation of EP2 receptors has the same effect [240] on ADP and collagen aggregation [239]. Similar self-regulation with opposing receptor functions is observed in platelets where prostanoid EP2 and EP3 receptors differentially modulate activation [241]. An EP3-selective PGE2 analog, 11-deoxy-16,16-dimethyl PGE2, exaggerates intracellular calcium release by ADP, whereas EP2 selective agonist butaprost inhibits the secondary wave of ADP-induced aggregation.

Similar studies, in attempt to identify the differential influence of EP2/EP4 platelet stimulation and EP3 platelet inhibition, have also indirectly provided insight into unraveling the complexity of the downstream signaling pathways of thromboxane. Stimulating platelets with the thromboxane analogue U46619 in combination with selective EP3 or EP4 antagonists showed that EP3 antagonism eliminated the synergistic aggregation effect without affecting aggregation directly [242]. The logic behind this study was to evaluate the therapeutic potential of PGE2 inhibition owing to the overlapping ligand selectivity of these two receptors. They noted relatively low levels of plaque PGE2, limiting the therapeutic implications, but highlighting the role of EP3 stimulation in the process and supporting the notion that Gi stimulation does not produce aggregation on its own, but makes the cell more sensitive to calcium stimulation by reducing cAMP.

PGE2, however, is found at lower levels in atherosclerotic lesions than PGE1 [243]. The relative abundance of these ligands deserves consideration in light of their overlapping specificities and their complex effects. PGE1 and PGE2, for instance, both stimulate EP3 receptors, and both balance the resulting Gi effect by stimulating Gs via either IP, in the case of PGE1, or EP2/EP4 in the case of PGE2 [235]. These redundant checks and balances keep the system in a dynamic equilibrium maintained through altering both ligand and receptor repertoires in response to each other. Despite the potent influence of PG on vasoconstriction and vasodilation, the influence of eicosanoids on hypertensive tone is neither limited to PG nor to the calcium/cAMP balance they maintain.

C-reactive protein

An emerging risk factor in cardiovascular disease is the biomarker of inflammation: C-reactive protein (CRP) [244, 245]. Though less predictive than the combination of traditional risk factors such as age, family history, and smoking [246], CRP may be a superior biomarker to the more commonly used LDL [247] and has been recently recognized as an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease [244, 248] as well as diabetes [249]. CRP increases along with inflammation, exists in circulating pentameric or bound monomeric forms [250], and instigates complement activation in response to exposed membrane phosphocholine [251].

As with many of the pathways involved in inflammation, positive feedback functions in both directions. Platelet activation converts native circulating pentameric CRP to the inflammatory monomeric CRP [252]. CRP similarly activates platelet aggregation and ATP release in a dose-dependent manner [253]. From the perspective of eicosanoid signaling, CRP modulates the COX-prostanoid pathway, suppressing prostacyclin synthesis and promoting thromboxane receptor transcription [254]. Additionally, CRP blood levels can be reduced by directly altering eicosanoid production with either aspirin treatment [255] or with omega-3 (EPA and DHA) supplementation [256]. Thus, CRP can repress cardioprotective eicosanoids, and eicosanoids can modulate CRP levels.

Leukotrienes

Leukotrienes are highly abundant in atherosclerotic plaques [257] and the 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP) gene (ALOX5AP) variants (13q12-13) increase leukotriene B4 (LTB4) production and confer risk for MI and stroke [258]. Though CysLT receptors are predominantly found on mast cells, eosinophils, and endothelia, CysLT1 receptors exhibit a potent smooth muscle contractile response [259]. CysLT2 antagonist decreased neutrophil infiltration and leukocyte adhesion molecule expression reducing ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) damage from myocardial infarction, a process resulting from reactive oxygen species formation as part of the innate inflammatory response [260]. CysLT2R acts exclusively through Gq calcium mobilization in endothelia [261], whereas CysLT1R promiscuously couples with Gq and Gi [262]. Overexpression of CysLT2R increases endothelial permeability and aggravates I/R injury [263, 264], where selective CysLT2R antagonism reduces post ischemia–reperfusion. Similarly, CysLT1 antagonism with monetlukast reduces ischemic injury [265] and associated histopathological alterations [266].

The BLT1R receptor, a Gq-coupled, LTB4 sensitive receptor in VSMC [267], when knocked out, decreases atherosclerosis in a hyperlipid rat model [268], via the role in smooth muscle recruitment [269, 270]. Similarly, BLT antagonism improves atherosclerotic burden in mice [271] via reduced monocyte recruitment and foam cell formation. A CysLT1R antagonist, montelukast, inhibits atherosclerotic lesion size and intimal hyperplasia through effects on VSMC proliferation [272, 273]. Montelukast treatment also improves endothelial cell function, reduces vascular ROS production, and ameliorates plaque generation in mice [274]. Just as hyperglycemia promotes oxidative stress, dyslipidemia leads to hyperglycemia via insulin resistance. As with hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia is also associated with hyperactive platelets [275], likely through increased isoprostane and thromboxane production [189].

Prostaglandin D2

Like LT, prostaglandin D2 is more commonly associated with asthma and allergy [276] than with cardiovascular disease, though PGD2 does play an increasingly recognized roll in hemostasis [277, 278]. Serum levels of localin-type prostaglandin D synthase (L-PGDS) are strongly associated with hypertension [279] and are predictive of coronary artery disease severity in patients undergoing diagnostic angiography [280]. Another clinical study showed that increased serum L-PGDS correlates with increased coronary artery intima-media complex thickness and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity [281]. In summary, increased serum L-PGDS associates with overall risk factor profile and measures of atherosclerotic progression.

Receptors DP1 and newly discovered CRTh2 (DP2) have distinct structural characteristics and ligand selectivity [282], and are both stimulated by PGD2. CRTh2, is also activated by TxB2, the metabolite of TxA2 [283]. PGD2 is formed by immune cells [284] that accumulate in atherosclerotic lesions [285]. PGD2 inhibits iNOS expression [286] and L-PGDS knockout mice display aggravated obesity and atherosclerosis [287].

Challenges and opportunities in eicosanoid receptor pharmacology

Only recently have the importance of eicosanoid roles in the development of clinical human atherothrombosis become recognized. These became particularly apparent after identifying the cardioprotective role of selective COX-1 inhibition (e.g., low-dose aspirin) [288] and the clear cardiovascular adverse effects of selective COX-2 inhibition (e.g., rofecoxib) [289]. These have all been further supported by many elegant mouse studies [85, 290]. It now remains to be seen whether direct targeting of the downstream receptors will be of any further benefit (and cost effective). For such advances, understanding the structure/function of each receptor in a defined tissue is critical. Naturally occurring mutations can be used clinically as “human genetic functional knockouts” to study effects on human tissues and disease; however, it is becoming apparent that each individual mutation may provide specific structural perturbations that may lead to quite different signaling defects (Table 2). Moreover, deciphering such processes as dimerization and alternative splicing, and understanding defects in such processes, will provide insights into the modulation of human disease. Indeed, targeting eicosanoid-related disease processes at the level of their respective GPCRs may require conformation-specific ligands. Owing to the complexity of receptor structure and function [291], in combination with the complexity of the inflammatory basis of atherothrombosis [2], the intimate involvement of platelets [10] and many other cardiovascular cells, and the overarching influence of risk factors such as dyslipidemia [292], investigations into eicosanoid signaling will continue to play a central role in seeking a unifying picture of atherothrombotic development.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for our outstanding eicosanoid centric colleagues who have collaborated with us in our studies on eicosanoids and cardiovascular disease. In pursuing our studies, we are also grateful for generous funding from NIH (NHLBI) and the American Heart Association. This review is dedicated to the memory of Har Gobind Khorana (1922–2011) a brilliant scientist and mentor without whom many of these studies would not have been possible.

References

- 1.Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber C, Noels H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1410–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson SP. Arterial thrombosis—insidious, unpredictable and deadly. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1423–1436. doi: 10.1038/nm.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird DA, et al. Receptors for oxidized low-density lipoprotein on elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages can recognize both the modified lipid moieties and the modified protein moieties: implications with respect to macrophage recognition of apoptotic cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1999;96(11):6347–6352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis: the road ahead. Cell. 2001;104(4):503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Libby P, et al. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: transition from theory to practice. Circ J. 2010;74(2):213–220. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocha VZ, Libby P. Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6(6):399–409. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420(6917):868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angiolillo DJ, Ueno M, Goto S. Basic principles of platelet biology and clinical implications. Circ J. 2010;74(4):597–607. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufmann BA, et al. Molecular imaging of the initial inflammatory response in atherosclerosis: implications for early detection of disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(1):54–59. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.196386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun OO, et al. Primary and secondary capture of platelets onto inflamed femoral artery endothelium is dependent on P-selectin and PSGL-1. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;592(1–3):128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furie B, Furie BC. Role of platelet P-selectin and microparticle PSGL-1 in thrombus formation. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10(4):171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theilmeier G, et al. Endothelial von Willebrand factor recruits platelets to atherosclerosis-prone sites in response to hypercholesterolemia. Blood. 2002;99(12):4486–4493. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruggeri ZM. Platelets in atherothrombosis. Nat Med. 2002;8(11):1227–1234. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gawaz M, Langer H, May AE. Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3378–3384. doi: 10.1172/JCI27196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson SP. The growing complexity of platelet aggregation. Blood. 2007;109(12):5087–5095. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-027698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denis CV, Wagner DD. Platelet adhesion receptors and their ligands in mouse models of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(4):728–739. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000259359.52265.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varga-Szabo D, Pleines I, Nieswandt B. Cell adhesion mechanisms in platelets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(3):403–412. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennings LK. Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102(2):248–257. doi: 10.1160/TH09-03-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapoor JR (2008) Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med 358(15):1638 (author reply 1638–1639) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Davi G, Patrono C. Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(24):2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yousuf O, Bhatt DL. The evolution of antiplatelet therapy in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(10):547–559. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirsh J. Hyperactive platelets and complications of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(24):1543–1544. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706113162410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panigrahy D, et al. Cytochrome P450-derived eicosanoids: the neglected pathway in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(4):723–735. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9264-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nithipatikom K, Gross GJ. Review article: epoxyeicosatrienoic acids: novel mediators of cardioprotection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2010;15(2):112–119. doi: 10.1177/1074248409358408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(5):986–1000. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sala A, Folco G, Murphy RC. Transcellular biosynthesis of eicosanoids. Pharmacol Rep. 2010;62(3):503–510. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(10)70306-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rokach J, et al. Total synthesis of isoprostanes: discovery and quantitation in biological systems. Chem Phys Lipids. 2004;128(1–2):35–56. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen LJ. Isoprostanes: an overview and putative roles in pulmonary pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;280(6):L1067–L1082. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coleman RA, Smith WL, Narumiya S. International union of pharmacology classification of prostanoid receptors: properties, distribution, and structure of the receptors and their subtypes. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46(2):205–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drazen JM, et al. Comparative airway and vascular activities of leukotrienes C-1 and D in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77(7):4354–4358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasegawa S, et al. Functional expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptors on human platelets. Platelets. 2010;21(4):253–259. doi: 10.3109/09537101003615394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nonaka Y, Hiramoto T, Fujita N. Identification of endogenous surrogate ligands for human P2Y12 receptors by in silico and in vitro methods. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337(1):281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Node K, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science. 1999;285(5431):1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li N, et al. Use of metabolomic profiling in the study of arachidonic acid metabolism in cardiovascular disease. Congest Heart Fail. 2011;17(1):42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellien J, et al. Modulation of cytochrome-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids pathway: a promising pharmacological approach to prevent endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases? Pharmacol Ther. 2011;131(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Harris RC. Cytochrome P450 and arachidonic acid bioactivation: molecular and functional properties of the arachidonate monooxygenase. J Lipid Res. 2000;41(2):163–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleming I, et al. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor synthase (cytochrome P450 2C9) is a functionally significant source of reactive oxygen species in coronary arteries. Circ Res. 2001;88(1):44–51. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viswanathan S, et al. Involvement of CYP 2C9 in mediating the proinflammatory effects of linoleic acid in vascular endothelial cells. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003;22(6):502–510. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2003.10719328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.CDC Prevalence of coronary heart disease—United States, 2006–2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(40):1377–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Splansky GL, et al. The Third Generation Cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(11):1328–1335. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart ST, Cutler DM, Rosen AB. Forecasting the effects of obesity and smoking on U.S. life expectancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(23):2252–2260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0900459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ADVANCE Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.ACCORD Group Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duckworth W, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):129–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cushman WC, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zoungas S, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(15):1410–1418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher M, Loscalzo J. The perils of combination antithrombotic therapy and potential resolutions. Circulation. 2011;123(3):232–235. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820841ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Angiolillo DJ, et al. Differential effects of omeprazole and pantoprazole on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel in healthy subjects: randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover comparison studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(1):65–74. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson PW, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson PWF, Castelli WP, Kannel WB. Coronary risk prediction in adults (The Framingham Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 1987;59(14):G91–G94. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yanes LL, Reckelhoff JF. Postmenopausal hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(7):740–749. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schenck-Gustafsson K, et al. EMAS position statement: managing the menopause in the context of coronary heart disease. Maturitas. 2011;68(1):94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Egan K, et al. COX-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science. 2004;306(5703):1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner EC, Kinsella BT. Estrogen increases expression of the human prostacyclin receptor within the vasculature through an ERalpha-dependent mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2010;396(3):473–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ridker PM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(13):1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith DD, et al. Increased aortic atherosclerotic plaque development in female apolipoprotein E-null mice is associated with elevated thromboxane A2 and decreased prostacyclin production. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;61(3):309–316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leslie CA, Gonnerman WA, Cathcart ES. Gender differences in eicosanoid production from macrophages of arthritis-susceptible mice. J Immunol. 1987;138(2):413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou Y, et al. Gender differences of renal CYP-derived eicosanoid synthesis in rats fed a high-fat diet[ast] Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(4):530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ward NC, et al. Urinary 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid excretion is associated with oxidative stress in hypertensive subjects. Free Radical Biol Med. 2005;38(8):1032–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ward NC, et al. Urinary 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid is associated with endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation. 2004;110(4):438–443. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136808.72912.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yanes LL, et al. Postmenopausal hypertension: role of 20-HETE. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300(6):R1543–R1548. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00387.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liang C-J, et al. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid inhibits ATP-induced COX-2 expression via peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-α in vascular smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(4):815–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tunctan B et al (2011) Contribution of vasoactive eicosanoids and nitric oxide production to the effect of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, NS-398, on endotoxin-induced hypotension in rats. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, pp 877–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Tsai IJ, et al. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthesis is increased in human neutrophils and platelets by angiotensin II and endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300(4):H1194–H1200. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00733.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lange A, et al. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-induced vasoconstriction and inhibition of potassium current in cerebral vascular smooth muscle is dependent on activation of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(43):27345–27352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gebremedhin D, et al. Cat cerebral arterial smooth muscle cells express cytochrome P450 4A2 enzyme and produce the vasoconstrictor 20-HETE which enhances L-type Ca2+ current. J Physiol. 1998;507(3):771–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.771bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiowski W, et al. Endothelin-1-induced vasoconstriction in humans. Reversal by calcium channel blockade but not by nitrovasodilators or endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Circulation. 1991;83(2):469–475. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nelson MT, et al. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1990;259(1):C3–C18. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.1.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;303(20):2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(7):590–599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Collaboration APCS. The impact of cardiovascular risk factors on the age-related excess risk of coronary heart disease. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):1025–1033. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graessler J, et al. Top-down lipidomics reveals ether lipid deficiency in blood plasma of hypertensive patients. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quehenberger O, Dennis EA. The human plasma lipidome. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1812–1823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1104901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gryglewski RJ. Prostacyclin among prostanoids. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60(1):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM. Hypertension. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;303(20):2098. doi: 10.1001/jama.303.20.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blaustein MP, et al. How NaCl raises blood pressure: a new paradigm for the pathogenesis of salt-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;302:H1031–H1049. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00899.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Beckett NS, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. Tight blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304(1):61–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fisher JP, Paton JFR (2011) The sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: implications for hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. doi:10.1038/jhh.2011.66 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Orlov SN, Tremblay J, Hamet P. cAMP signaling inhibits dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ influx in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 1996;27(3):774–780. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kawabe J, Ushikubi F, Hasebe N. Prostacyclin in vascular diseases. Recent insights and future perspectives. Circ J. 2010;74(5):836–843. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stitham J, et al. Prostacyclin: an inflammatory paradox. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:24. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2011.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cheng Y, et al. Role of prostacyclin in the cardiovascular response to thromboxane A2. Science. 2002;296(5567):539–541. doi: 10.1126/science.1068711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yu Y, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent prostacyclin formation and blood pressure homeostasis. Circ Res. 2009;106(2):337–345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.204529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arehart E, et al. Acceleration of cardiovascular disease by a dysfunctional prostacyclin receptor mutation: potential implications for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition. Circ Res. 2008;102(8):986–993. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jia Z, et al. Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 increases sensitivity to salt loading and angiotensin II infusion. Circ Res. 2006;99(11):1243–1251. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251306.40546.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jia Z, Wang H, Yang T. Mice lacking mPGES-1 are resistant to lithium-induced polyuria. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297(6):F1689–F1696. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00117.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Woodward DF, Jones RL, Narumiya S. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXXIII: classification of prostanoid receptors, updating 15 years of progress. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63(3):471–538. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Suzuki J-I, et al. Roles of prostaglandin E2 in cardiovascular diseases focus on the potential use of a novel selective EP4 receptor agonist. Int Heart J. 2011;52(5):266–269. doi: 10.1536/ihj.52.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stock JL, et al. The prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptor mediates pain perception and regulates blood pressure. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(3):325–331. doi: 10.1172/JCI6749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guan Y, et al. Antihypertensive effects of selective prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 1 targeting. J Clin Investig. 2007;117(9):2496–2505. doi: 10.1172/JCI29838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ai D, et al. Angiotensin II up-regulates soluble epoxide hydrolase in vascular endothelium in vitro and in vivo. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2007;104(21):9018–9023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703229104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Campbell WB, et al. Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res. 1996;78(3):415–423. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bellien J, Thuillez C, Joannides R. Contribution of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors to the regulation of vascular tone in humans. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22(4):363–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhao X, et al. Salt-sensitive hypertension after exposure to angiotensin is associated with inability to upregulate renal epoxygenases. Hypertension. 2003;42(4):775–780. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000085649.28268.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fitzpatrick FA, et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity and platelet aggregation by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Influence of stereochemistry. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(32):15334–15338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Krötz F, et al. Membrane potential-dependent inhibition of platelet adhesion to endothelial cells by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Arteri Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(3):595–600. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000116219.09040.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Krotz F, et al. Membrane-potential-dependent inhibition of platelet adhesion to endothelial cells by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(3):595–600. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000116219.09040.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maier KG, Roman RJ. Cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of renal function. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10(1):81–87. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Athirakul K, et al. Increased blood pressure in mice lacking cytochrome P450 2J5. FASEB J. 2008;22(12):4096–4108. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-114413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Campbell WB, et al. 14,15-Dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid relaxes bovine coronary arteries by activation of KCa channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282(5):H1656–H1664. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00597.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Imig JD, et al. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition lowers arterial blood pressure in angiotensin II hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39(2):690–694. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liu Y, et al. The antiinflammatory effect of laminar flow: the role of PPARγ, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, and soluble epoxide hydrolase. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(46):16747–16752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508081102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Behm DJ, et al. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids function as selective, endogenous antagonists of native thromboxane receptors: identification of a novel mechanism of vasodilation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328(1):231–239. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yamagishi K, et al. Fish, ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and mortality from cardiovascular diseases in a nationwide community-based cohort of Japanese men and women: the JACC (Japan Collaborative Cohort Study for Evaluation of Cancer Risk) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(12):988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.De Caterina R. n-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1008153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nakayama M, et al. Low dose of eicosapentaenoic acid inhibits the exaggerated growth of vascular smooth muscle cells from spontaneously hypertensive rats through suppression of transforming growth factor-beta. J Hypertens. 1999;17(10):1421–1430. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917100-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]