Abstract

Plants are exposed to different external conditions that affect growth, development, and productivity. Water deficit is one of these adverse conditions caused by drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures. Plants have developed different responses to prevent, ameliorate or repair the damage inflicted by these stressful environments. One of these responses is the activation of a set of genes encoding a group of hydrophilic proteins that typically accumulate to high levels during seed dehydration, at the last stage of embryogenesis, hence named Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) proteins. LEA proteins also accumulate in response to water limitation in vegetative tissues, and have been classified in seven groups based on their amino acid sequence similarity and on the presence of distinctive conserved motifs. These proteins are widely distributed in the plant kingdom, from ferns to angiosperms, suggesting a relevant role in the plant response to this unfavorable environmental condition. In this review, we analyzed the LEA proteins from those legumes whose complete genomes have been sequenced such as Phaseolus vulgaris, Glycine max, Medicago truncatula, Lotus japonicus, Cajanus cajan, and Cicer arietinum. Considering their distinctive motifs, LEA proteins from the different groups were identified, and their sequence analysis allowed the recognition of novel legume specific motifs. Moreover, we compile their transcript accumulation patterns based on publicly available data. In spite of the limited information on these proteins in legumes, the analysis and data compiled here confirm the high correlation between their accumulation and water deficit, reinforcing their functional relevance under this detrimental conditions.

Keywords: legumes, common bean, soybean, Medicago, LEA proteins, water deficit, abiotic stress

Introduction

Plants are subjected to different stresses (abiotic and biotic) along their life cycles and have developed different responses to alleviate the damage, and survive to these impaired conditions (Bartels and Sunkar, 2005). Abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, osmotic, cold, and freezing temperatures produce cellular water deficit, which leads to the accumulation of a group of highly hydrophilic proteins, named LEA proteins (for Late Embryogenesis Abundant) (for review Battaglia et al., 2008; Bies-Etheve et al., 2008; Hundertmark and Hincha, 2008). These proteins are not only associated to water deficit caused by environmental changes but also to water limitation produced during plant development under optimal growth conditions, such as during development of seeds and pollen grains, or some stages of shoot and root development (Colmenero-Flores et al., 1999; Vicient et al., 2000; Sheoran et al., 2006). Some LEA proteins have also been found associated to vascular tissues, and also in meristematic regions (Cheng et al., 1996; Colmenero-Flores et al., 1999; Moreno-Fonseca and Covarrubias, 2001). Their high accumulation in embryos of dormant seeds and in mature pollen grains, both desiccation resistant structures able to withstand dehydration for long periods, led to propose a role for these proteins in plant tolerance to water scarcity [for review see Dure III et al. (1981), Battaglia et al. (2008), Bies-Etheve et al. (2008), Hundertmark and Hincha (2008)].

LEA proteins have been found widely distributed in the plant kingdom, from algae (Honjoh et al., 1995; Joh et al., 1995), moss (Saavedra et al., 2006), ferns (Raghavan and Kamalay, 1993), to angiosperms. Interestingly, LEA-like proteins also accumulate in anhydrobiotic invertebrates and in some bacterial species in response to water limitation (Stacy and Aalen, 1998; Browne et al., 2004; Goyal et al., 2005a; Kikawada et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Hand et al., 2011; Clark et al., 2012).

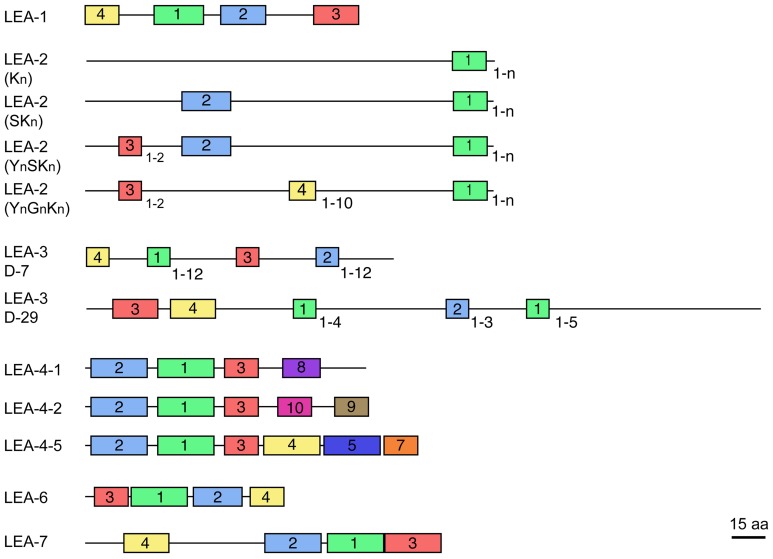

Most LEA proteins identified to date belong to hydrophilins, a widely distributed group of proteins characterized by a high content of charged amino acid residues, as well as glycine or other small amino acids such as alanine, serine, or threonine. Moreover, most hydrophilins lack tryptophanes and cysteines (Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000). These physicochemical properties led to propose that hydrophilins are unstructured proteins in aqueous solutions (Dure, 1993; Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000), which has been shown for some LEA proteins [see for review Olvera-Carrillo et al. (2011)]. Analyses of LEA protein amino acid sequences recognize seven different groups, each one showing distinctive motifs (LEA1 – LEA7). In particular, for groups 2, 3, and 4 different protein variants have been found showing a particular organization of their corresponding motifs (Figure 1). Significant sequence similarity has not been detected between the seven LEA protein groups. Because of their more hydrophobic nature and higher structural order, group 5 LEA proteins are not classified as hydrophilins (Dure III et al., 1989; Battaglia et al., 2008). Given the high heterogeneity and little information on this group, it was not included in this review.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of motifs distinctive for each LEA protein group (see Table 2). The different protein variants found in groups 2, 3, and 4 are shown. Colored blocks indicate the distribution of distinctive motifs in each group; equal colors between groups do not mean sequence similarity. Numbers at the right bottom of some motifs indicate the maximum number of repetitions detected. Protein diagrams are drawn to scale as indicated, considering a mean protein size for each group.

A variety of studies have shown a potential role for LEA proteins in stress tolerance. Their function in protein protection upon water deficit was demonstrated by in vitro experiments, where different hydrophilins, including LEA proteins from groups 2, 3, and 4, were able to prevent the inactivation of enzymes such as LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) or MDH (malate dehydrogenase) upon different dehydration levels (Goyal et al., 2005b; Reyes et al., 2005, 2008). Similarly, protective properties were also detected during freeze-thaw in vitro assays (Hara et al., 1999; Reyes et al., 2008). Interestingly, in these latter assays, a particular protective role was detected for the K-segment, a LEA2 protein distinctive motif, and for a conserved region in LEA4 proteins (Reyes et al., 2008). Because in these assays, 1:1 ratios between LEA and target proteins were enough to provide protection, it was proposed that this protective activity is carried out by protein-protein interactions (Reyes et al., 2005; Olvera-Carrillo et al., 2011). More severe in vitro dehydration assays, using high LEA: target protein ratios, suggested that some LEA and LEA-like proteins are also able to avoid protein aggregation (Goyal et al., 2005b; Chakrabortee et al., 2007). In addition, some reports suggest that the presence of sugars can enhance LEA proteins protecting effect under dehydration (Black et al., 1999; Wolkers et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2010).

Membrane stabilization has been another function attributed to LEA proteins. Most evidence comes from in vitro experiments, where LEA2 proteins (dehydrins) were found associated to anionic phospholipid vesicles (Koag et al., 2003, 2009). Also, other assays suggested that dehydrin addition maintain the functional membrane structure under freezing temperatures (Ismail et al., 1999; Kosová et al., 2007). These data are in agreement with reports that have detected binding of dehydrins to membranes or phospholipids; however, all these results have been obtained from in vitro experiments or with isolated membranes. In contrast, no conclusive information is available regarding their membrane association by intracellular localization experiments using antibodies or fluorescent translational fusions, which however, have contributed to establish dehydrins location in cytosol, nuclei, chloroplast, protein and lipid bodies, mitochondria, and plasmodesmata [for review Rorat (2006)].

In the case of LEA proteins from other groups, most of them have been shown to be cytosolic; however, some have also been localized in chloroplast (Ndong et al., 2002), mitochondria (Grelet et al., 2005; Tolleter et al., 2010) and even in nucleus (Goday et al., 1994; Houde et al., 1995; Colmenero-Flores et al., 1999; Riera et al., 2004; Gai et al., 2011; Duan and Cai, 2012). The mitochondrial localization of pea (Pisum sativum) LEA3 proteins correlates with their ability to protect some mitochondrial enzymes such as rhodanese and fumarase from inactivation induced by in vitro dehydration (Grelet et al., 2005). Their nuclei localization has also been associated with binding to DNA for some LEA2, LEA4, and LEA7 proteins (Colmenero-Flores et al., 1999; Maskin et al., 2007; Hara et al., 2009).

Additional roles have been suggested for these proteins such as ion sequestration, in particular, for LEA2 and LEA4 proteins, where histidine-containing motifs seem to be responsible of binding divalent cations (Hara et al., 2005). This is the case of soybean LEA4-5 proteins (GmPM1: Glyma19g32920.1 and GmPM9: Glyma03g30040.1), which bind Fe+3, Ni+2, Cu+2 and Zn+2 (Liu et al., 2011). In vitro experiments using a citrus dehydrin, or GmPM1 and GmPM9 indicate that these proteins reduce the levels of OH· radical; hence, suggesting an oxidant scavenger activity associated to an increased ion concentration (Hara et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2011).

Over-expression experiments in different organisms have also contributed to support a role of LEA proteins in tolerance to water scarcity. For instance, expression of soybean PM2 protein (LEA3) conferred Escherichia coli with the ability to grow under high salt or upon extreme temperature treatments (Liu and Zheng, 2005; Liu et al., 2010). Recently, it has been shown that a LEA3-like protein from the brine shrimp Artemia franciscana increases cellular viability after desiccation and hyperosmotic stress of Drosophila melanogaster cells (Marunde et al., 2013). In plants, a number of reports indicate that over-expression of LEA proteins from various groups confers tolerance to a variety of water deficit treatments (Puhakainen et al., 2004; Eriksson and Harryson, 2011; Duan and Cai, 2012). More significantly, it has been shown that the deficiency of one or two of the three LEA4 proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana is enough to cause water deficit susceptibility (Olvera-Carrillo et al., 2010), showing their relevance in the plant adaptive response to this stress condition. This role is also endorsed for LEA2 proteins as indicated by the co-segregation of a dehydrin gene with chilling tolerance during cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) seedling emergence (Ismail et al., 1999).

Even though there is very limited information regarding the participation of LEA proteins in the plant response to biotic stress, it is known that over-expression of group 2 LEA proteins from Arabidopsis affects the expression of genes related to plant defense responses (e.g., pathogenesis-related proteins, PR) (Hanin et al., 2011); also, it has been reported that a group 3 LEA protein from maize is up-regulated in response to bacterial infection and that its over-expression in tobacco plants improves tolerance to Pseudomonas syringae (Liu et al., 2013). In addition, the over-expression in Escherichia coli of groups 2 and 4 LEA proteins causes bacterial growth inhibition (Campos et al., 2006; Hanin et al., 2011). These observations have led to the speculation that the antibacterial activity of some dehydrins may be part of a defense mechanism against opportunistic bacterial infections commonly occurring during water deficit conditions, a hypothesis awaiting exploration.

As it has been described above, the responsiveness of the different LEA genes to water deficit is common, however, some of them have also been found to be responsive to other stressful conditions such as ion toxicity, oxidation, or high temperatures, and in some cases a correlation has been found with the ability of LEA proteins to bind different cations, including Fe+3, Ni+2, Cu+2, or to confer tolerance to these stress conditions [for review Hanin et al. (2011)]. Even though these observations may be difficult to integrate, the wide variety of functions that have been attributed to these proteins could be related to their selection throughout evolution not only by low water availability but also by other intrinsically associated conditions; that would be the case of high temperatures or the generation of high ion concentrations and reactive oxygen species, among other effects. In addition, the flexibility of their structure should also be considered, as for many IUPs it has been associated to multifunctionality (Hara, 2010; Liu et al., 2010, 2013; Olvera-Carrillo et al., 2011; Dominguez et al., 2013), an appealing characteristic that has been poorly explored in these proteins.

LEA proteins in legumes

To gain insight into the conservation patterns of the different distinctive motifs identified in LEA proteins, in this work we analyzed the different legume LEA proteins sequences using the information available in the legume genome sequence databases (Phaseolus vulgaris: http://www.phytozome.net/search.php?org=Org_Pvulgaris_v1.0; Glycine max: http://www.phytozome.net/search.php?org=Org_Gmax_v1.1; Medicago truncatula: http://medicago.jcvi.org/cgi-bin/medicago/overview.cgi; Lotus japonicus: http://www.kazusa.or.jp/lotus/), Cajanus cajan (http://cajca.comparative-legumes.org/) (Varshney et al., 2012) and Cicer arietinum (http://cicar.comparative-legumes.org/) (Varshney et al., 2013) (see Table 1). For this, protein sequences from each group were compared and the motifs described for Viridiplantae were analyzed (see Table 2 and Figure 1). In addition to the strong similarity between those motifs previously identified (Battaglia et al., 2008), a new Gly-rich region was found in some legume LEA2 proteins. The most conserved motif in this group is a repetitive 15-mer motif, EKKGIMDKIKEKLPG, called K-segment because of its richness in lysine (K) residues. Additional common motifs are the Y- and S-segments. When present, the S-segment usually precedes the K-segment (Campbell and Close, 1997). The new glycine-rich region detected shows a repetitive large motif represented by the sequence [YF]T[GD]DT[GN][RK]QH[GD]T. This sequence is present up to 10-times in a protein, as in the case of the polypeptide encoded by the Phvul004G158800.1 gene from P. vulgaris. Two dehydrins with Gly-rich motifs have been described. One from Vigna radiata, VrDhn1, a novel Y2K dehydrin detected in seeds and induced by various abiotic stresses or ABA treatment (Lin et al., 2012), and Mat1 (Glyma07g10030.1) from soybean, which has a homolog called Mat9 (Glyma09g31740.2), induced upon severe water deficit (Whitsitt et al., 1997; Momma et al., 2003). This motif was only detected in LEA2 proteins from Phaseoloid species, which include several legumes more adapted to tropical climates. Because this group is considered one of the youngest groups among the three legume sub-families (Gepts et al., 2005), it can be suggested that this motif is of recent appearance. It is worth mentioning that this motif and its repetitions (4–10X) always were found to be present between segments-Y and -K, which suggests a common ancestor for this type of dehydrins.

Table 1.

Legume LEA proteins.

LEA genes found in different legume genomes and compared with Arabidopsis thaliana genes. Phaseolus vulgaris (http://www.phytozome.net/search.php?org=Org_Pvulgaris_v1.0); Glycine max (http://www.phytozome.net/search.php?org=Org_Gmax_v1.1); Medicago truncatula (http://medicago.jcvi.org/cgi-bin/medicago/overview.cgi); Lotus japonicus (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/lotus/); Cajanus cajan (http://cajca.comparative-legumes.org/) and Cicer arietinum (http://cicar.comparative-legumes.org/). Asterisks indicate LEA2 proteins containing the Gly-rich motif.

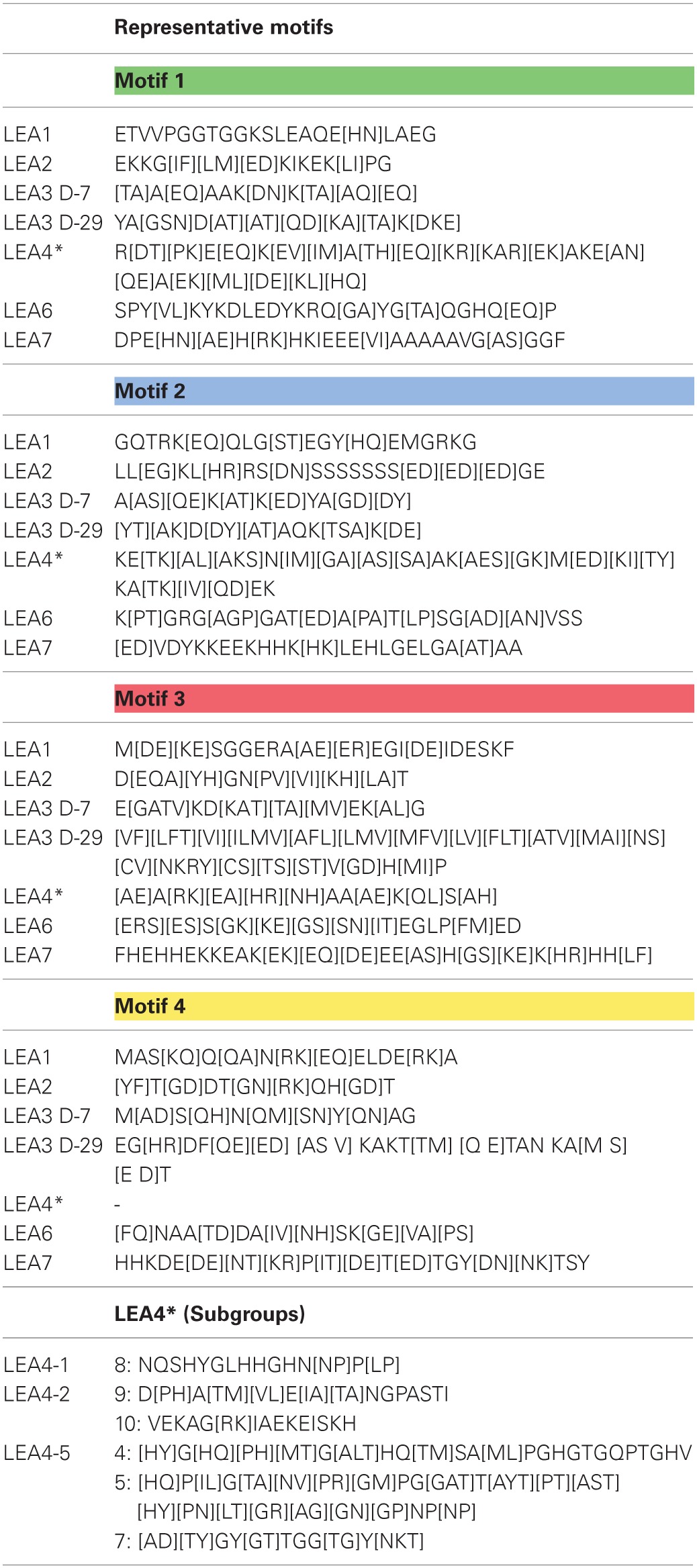

Table 2.

Distinctive motifs in the different groups of legume LEA proteins.

LEA protein motifs were discovered using MEME algorithm (4.9.0 version), with an optimum width between 6–25 amino acids, selecting a motif distribution of 0–1 or any number of repetitions (Bailey et al., 2009). The asterisk after LEA4 indicates that for LEA4 proteins, the specific motifs for each sub-group are shown in a separate block. Colors in top bars for every block correspond to those used in Figure 2 for each motif.

Structure

The LEA protein amino-acid composition predicted structural disorder along their sequence (Dure, 1993; Garay-Arroyo et al., 2000), and thus inscribed them as intrinsically unstructured proteins (IUPs). Structural analyses using circular dichroism (CD) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy have shown that this is the case, at least, for some purified recombinant LEA proteins in aqueous solutions (Lisse et al., 1996; Thalhammer et al., 2010). For legume LEA proteins, this has been shown for LEA1 proteins such as GmD19 (Glyma03g07470.1), GmPM11 (Glyma03g07470), LEA2 as GmPM6 (Glyma09g31740.1-LEA2), LEA3 like GmPM30 (Glyma13g44020.1) and LEA4 (Glyma17g16620), where also a potential to attain a more ordered structure by using α-helical inducer agents (i.e., TFE) was observed (Soulages et al., 2002, 2003; Shih et al., 2004, 2010, 2012). In addition, conformational changes could be induced by slow or fast drying that lead to the formation of different α-helical proportions, depending on the protein (Shih et al., 2004, 2012). These results support the idea that unstructured LEA proteins are rather flexible proteins, able to adapt their conformation to the variable cellular environment as that produced by low water availability. It has been proposed that these conformational changes may facilitate interactions between LEA proteins and other macromolecules, such as other proteins, membranes and/or nucleic acids (Boudet et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2006; Maskin et al., 2007; Battaglia et al., 2008; Hundertmark et al., 2011, 2012; Olvera-Carrillo et al., 2011; Popova et al., 2011).

Transcript and protein expression patterns

LEA proteins have been detected in different stages of plant development in response to different water deficit conditions (salinity, freezing, and drought). In legumes, this has been reported for common bean, soybean or Medicago truncatula seedlings (Blackman et al., 1991; Hsing et al., 1995; Colmenero-Flores et al., 1997; Boudet et al., 2006; Aghaei et al., 2009; Le et al., 2012). As expected, their accumulation during late embryogenesis has also been documented in M. truncatula (Kalaiselvi and Manickam, 1999; Chatelain et al., 2012), G. max (Shih et al., 2004), Arachis hypogaea (Su et al., 2011) and P. vulgaris (Colmenero-Flores et al., 1997). Although very little information exists regarding the regulation of the expression of LEA genes, for some of them it is known that ABA induced their transcript accumulation (Colmenero-Flores et al., 1997; Bai et al., 2012).

To obtain more information on the accumulation patterns for legume LEA genes, we analyzed public microarrays and RNA-sequencing databases (M. truncatula:http://mtgea.noble.org/v2/blast_search_form.php; G. max: http://soykb.org/; Lotus japonicus: http://cgi-www.cs.au.dk/cgi-compbio/Niels/index.cgi?page=i). These data indicate that most legume LEA transcripts and proteins have similar accumulation patterns as those found for LEA proteins from other plant species. M. truncatula microarrays showed that water deficit conditions imposed with NaCl treatments (200 mM) induce the accumulation of transcripts from LEA genes of groups 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7. LEA1 transcripts were mostly detected during late embryogenesis as in Arabidopsis (Manfre et al., 2006, 2009), cotton (Dure III et al., 1989), and wheat (Litts et al., 1987, 1991). M. truncatula proteome analysis showed that MtEm6 protein is particularly present in newly emerged root tips (Zhang et al., 2006), as well as its transcript, as showed by microarray data.

Their presence in meristematic regions and root hairs

Interestingly, scrutiny of soybean microarray information showed that LEA transcripts from different groups accumulate in root tips and apical meristems, however, this just applies to some of them. For example, Glyma03g07470.1 (LEA1) was only detected in root tips, as did Glyma04g01130.1 (LEA2), and Glyma16g28150.1 (LEA7). All LEA3 and LEA4 transcripts accumulate in root tips except Glyma10g26440.1 (LEA3), Glyma17g04550.1 (LEA3), and Glyma09g17200.1 (LEA4). Accumulation in apical meristems was detected for Glyma04g01130.1 (LEA2), Glyma17g16620.1 (LEA3), and Glyma13g44020.1 (LEA3), all LEA 4 except Glyma05g23680.1, and all LEA7 transcripts. While soybean LEA6 transcripts were not detected in meristems, the transcript and protein for its homologous gene accumulate in vegetative and root meristems from principal and lateral roots of P. vulgaris (Colmenero-Flores et al., 1999; Moreno-Fonseca and Covarrubias, 2001). These observations strongly support the idea that LEA proteins could protect stem cells niches from changes in environmental water availability preventing and/or avoiding damage to these cells vital for plant survival.

A group of root epidermal cells, the atrichoblasts, has a specific cell fate to develop and differentiate as root hairs; they are formed by one tubular cell with polar growth (Cárdenas, 2009). Root hairs play a crucial role in plants, because water and nutrient uptake from soil occur principally through them. In legumes, root hairs have an additional role, they are the cells that interact, recognize and constitute the entrance of their symbiont, the rhizobial bacteria (Goormachtig et al., 2004). In these cells, LEA proteins have been detected in non-legumes growing under optimal irrigation conditions, as shown for AtEm6, a LEA1 gene (Vicient et al., 2000). Legume LEA transcript accumulation in root hairs was analyzed from a public database generated by comparing soybean transcriptome sequences obtained from free—or B. japonicum—inoculated root hairs (Libault et al., 2010a). Interestingly, LEA transcripts from all groups were found to accumulate in root hairs of non-infected plants (Figure 2), such as LEA2 (Glyma04g01130.1, Glyma04g01180.1, Glyma07g10030.1, and Glyma09g31740.1), LEA3, LEA4 (all), LEA6 (Glyma17g17860.1), and LEA7 (Glyma16g28150.1); however, none of them showed higher accumulation by rhizobia infection. Analysis of a proteome from isolated root hair cells identified the accumulation of only three LEA proteins: Glyma13g31120; Glyma03g34680 (LEA3), and Glyma04g01130.1 (LEA2), most probably due to the limitations inherent to the sensitivity of detection and protein extraction methods, and the properties of the proteins.

Figure 2.

LEA gene expression as detected by Libault et al. (2010a), using Glycine max RNA isolated from un- and infected-root hair cells harvested after 12 h inoculation. Infection was done with B. japonicum.

Accumulation in nodules

Nitrogen fixation is one of the fundamental processes in nature, carried out by N2 fixing-organisms. In some cases, this activity is possible because the ability of some bacteria to establish symbiosis with legumes, a process that implies a perfect coordination between the plant and the bacteria and that results in the formation of a new organ, the nodule, where nitrogen fixation occurs. Rhizobium is a bacterial group that by means of a fine molecular communication detects, recognizes and establishes symbiosis with plants. In the nodule, rhizobia develop as bacteroids that will be the N2 fixation competent bacterial stage (Oldroyd and Downie, 2008). Because the relevance of nodules in this function, the accumulation of LEA proteins and their transcripts was investigated in these organs from the M. truncatula Gene Expression Atlas (MtGEA) Project (Benedito et al., 2008) and G. max RNA-Seq atlas (Libault et al., 2010b; Severin et al., 2010), where some expression patterns are available. The results showed that LEA genes are expressed in nodules; however, we did not find representatives for all groups (Figure 3). LEA1 and LEA3 transcripts were not detected in these two legumes. The identified LEA transcripts corresponded to group 2 (Medtr7g086340.1, Medtr3g117290.1, and Glyma04g01130), group 4 (only one from M. truncatula, Medtr7g093140.1- LEA4-5 in 4 dpi nodule primordia), group 6 (G. max LEA6 genes), and group 7 (only one gene from G. max, Glyma16g28150.1).

Figure 3.

LEA gene expression patterns obtained using RNA isolated from Glycine max(A) or Medicago truncatula(B) nodules. (Benedito et al., 2008; Libault et al., 2010b; Severin et al., 2010; Joshi et al., 2012). dpi: days post-infection.

We found differences between the expression of LEA genes in M. truncatula and G. max and also between the different groups of LEA proteins (see Figure 3). LEA2 transcripts were detected in both species for genes Medtr7g086340.1, Medtr3g117290.1, and Glyma04g01130. Only one LEA4 protein was detected in primordia (4 days after inoculation) of M. truncatula (Medtr7g093140.1- LEA4-5), while all LEA6 genes from G. max were detected in nodules. From group 7 only one gene (Glyma16g28150.1) was found. A significant increase in the accumulation of two group 2 LEA protein transcripts (GmLEA8 and GmLEA10) has also been detected in soybean roots after 35 days of inoculation with Bradyrhizobium japonicum in well-watered plants; unexpectedly, lower accumulation levels of both transcripts were found in drought-stressed plants after the same inoculation time, suggesting that these LEA proteins may play a role during B. japonicum infection, induced by the “stress” caused during this process and/or by some developmental cue. The accumulation patterns for these transcripts have been also obtained from the corresponding nodules, where transcripts were not detected in well-irrigated plants, while nodules from drought-stressed plants, as expected, showed increased accumulation levels for both LEA mRNAs (Porcel et al., 2005). The response of these two genes (GmLEA8 and GmLEA10) was also examined in soybean plants colonized by the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus mosseae, grown under optimal irrigation or stress conditions. Even though, roots of inoculated drought-stressed plants showed high accumulation of these transcripts, the accumulation levels were lower than non-inoculated stressed plants, supporting the idea that the association with mycorrhiza brings on a plant tolerance response possibly due to changes in root morphology produced by this symbiosis. Accordingly, no expression was detected upon mycorrhiza inoculation in contrast to the accumulation response to B. japonicum infection (Porcel et al., 2005).

Concluding remarks

LEA proteins have represented for a long time an enigma in plant biology. The lack of similarity to other proteins of known function and their high structural flexibility has hampered the progress regarding their activity and the implicated mechanisms. However, the high association between their accumulation and different levels of water deficit, caused during development or by the environment, has contributed to build hypotheses regarding their role in the plant tolerance to those conditions that produce low water availability, as drought, salinity, or extreme temperatures.

This has led to relevant advances concerning their transcript and protein accumulation and expression patterns in response to abiotic stress or throughout development, their participation in these processes, and their structural properties. The available information presents LEA proteins as a set of proteins whose participation in plant tolerance to water deficit conditions has gained experimental support, and also as proteins whose flexible structure turns them as a good model to find the functional relevance of this flexibility in the plant response to stress.

Because most of the information regarding LEA proteins has been obtained from Arabidopsis, in this work we have focused on relevant data reported from legumes, to explore whether the observations made in Arabidopsis can be extended to this family of plants, or whether legume LEA proteins present some distinctive structural or functional features.

The analysis of the compiled data from literature and from the available databases showed that most of the structural characteristics recognized in these proteins are conserved in their corresponding homologs in the different legume LEA protein groups; however, it also revealed an additional motif in LEA2 proteins not detected to date in other plant families. It is worthwhile mentioning that LEA7 proteins, a group not present in Arabidopsis but detected in many other species, is also in legumes. As expected, the transcript and protein accumulation patterns available show their responsiveness to water deficit imposed by salinity, high osmolarity, dehydration, and low temperatures, supporting their participation in legume responses to these stressful conditions.

Of particular interest was the finding that various LEA transcripts from all groups accumulate in meristematic regions, even in plants grown under optimal growth conditions supporting a protective role in these fragile but critical regions for plant adaptation and survival, as proposed by Olvera-Carrillo et al. (2010), given that the over-expression or deficiency of a LEA4 protein led to an increase or a reduction, respectively, in the number of floral and axillar buds in Arabidopsis plants subjected to water deficit treatments. Moreover, different LEA transcripts were also detected in root hairs, which as in the previous case are frail but essential organs not only for water absorption but also to establish symbiosis between legumes and rhizobia needed for nitrogen fixation. Nodules also contain some LEA proteins; however, not all LEA protein groups seem to be present in the different types of nodules. A more detailed analysis is required, where the transcript levels of LEA protein from different groups is determined considering different stages during nodule development. With this limited and heterogeneous information it is difficult to be certain of the absence of some LEA protein groups in nodules. Similarly, at this point proposing tentative roles of these proteins during nodule development under optimal conditions would be highly speculative.

The information in this work regarding LEA proteins in legumes exposes the relevance of these proteins in the response and adaptation of this family of plants to water limiting environments, as it has been shown in other species, and justifies further studies to understand their function and participation in the plant responses to stress and during development. Also, it opens new interesting avenues regarding their role in meristematic regions and other fragile organs, such as root hairs, of particular importance in legumes symbiosis. All this predicts an appealing scenario full of surprises and knowledge.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. L. Reyes for discussions and critical review and to CONACyT-Mexico (132258) and DGAPA-PAPIIT-UNAM (IN-208212) for generous financial support.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Groups of LEA proteins: LEA1

LEA2, LEA3, LEA4, LEA6, and LEA7.

References

- Aghaei K., Ehsanpour A. A., Shah A. H., Komatsu S. (2009). Proteome analysis of soybean hypocotyl and root under salt stress. Amino Acids 36, 91–98 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y., Yang Q., Kang J., Sun Y., Gruber M., Chao Y. (2012). Isolation and functional characterization of a Medicago sativa L. gene, MsLEA. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 2883–2892 10.1007/s11033-011-1048-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Boden M., Buske F. A., Frith M., Grant C. E., Clementi L., et al. (2009). MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acid Res. 37, W202–W208 10.1093/nar/gkp335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels D., Sunkar R. (2005). Drought and salt tolerance. Plant Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 24, 23–58 [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M., Olvera-Carrillo Y., Garciarrubio A., Campos F., Covarrubias A. A. (2008). The enigmatic LEA proteins and other hydrophilins. Plant Physiol. 148, 6–24 10.1104/pp.108.120725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedito V. A., Torres-Jerez I., Murray J. D., Andriankaja A., Allen S., Kakar K., et al. (2008). A gene expression atlas of the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 55, 504–513 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03519.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bies-Etheve N., Gaubier-Comella P., Debures A., Lasserre E., Jobet E., Raynal M., et al. (2008). Inventory, evolution and expression profiling diversity of the LEA (Late Embryogenesis Abundant) protein gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 67, 107–124 10.1007/s11103-008-9304-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M., Corbineau F., Gee H., Come D. (1999). Water content, raffinose, and dehydrins in the induction of desiccation tolerance in immature wheat embryos. Plant Physiol. 120, 463–472 10.1104/pp.011171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman S. A., Wettlaufer S. H., Obendorf R. L., Leopold A. C. (1991). Maturation proteins associated with desiccation tolerance in soybean. Plant Physiol. 96, 868–874 10.1104/pp.109.136697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudet J., Buitink J., Hoekstra F. A., Rogniaux H., Larré C., Satour P., et al. (2006). Comparative analysis of the heat stable proteome of radicles of Medicago truncatula seeds during germination identifies late embryogenesis abundant proteins associated with desiccation tolerance. Plant Physiol. 140, 1418–1436 10.1104/pp.105.074039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J. A., Dolan K. M., Tyson T., Goyal K., Tunnacliffe A., Burnell A. M. (2004). Dehydration-specific induction of hydrophilic protein genes in the anhydrobiotic nematode Aphelenchus avenae. Eukaryot. Cell 3, 966–975 10.1128/EC.3.4.966-975.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S. A., Close T. J. (1997). Dehydrins: genes, proteins, and associations with phenotypic traits. New Phytol. 137, 61–74 10.1104/pp.109.148379 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campos F., Zamudio F., Covarrubias A. A. (2006). Two different late embryogenesis abundant proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana contain specific domains that inhibit Escherichia coli growth. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 342, 406–413 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas L. (2009). New findings in the mechanisms regulating polar growth in root hair cells. Plant Signal. Behav. 4, 4–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabortee S., Boschetti C., Walton L. J., Sarkar S., Rubinsztein D. C., Tunnacliffe A. (2007). Hydrophilic protein associated with desiccation tolerance exhibits broad protein stabilization function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18073–18078 10.1073/pnas.0706964104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelain E., Hundertmark M., Leprince O., Gall S. L., Satour P., Deligny-Penninck S., et al. (2012). Temporal profiling of the heat-stable proteome during late maturation of Medicago truncatula seeds identifies a restricted subset of late embryogenesis abundant proteins associated with longevity. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 1440–1455 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02501.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J. C., Seeley K. A., Goupil P., Sung Z. R. (1996). Expression of DC8 is associated with, but not dependent on embryogenesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 31, 127–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M. S., Denekamp N. Y., Thorne M. A., Reinhardt R., Drungowski M., Albrecht M. W., et al. (2012). Long-term survival of hydrated resting eggs from Brachionus plicatilis. PLoS ONE 7:e29365 10.1371/journal.pone.0029365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmenero-Flores J. M., Campos F., Garciarrubio A., Covarrubias A. A. (1997). Characterization of Phaseolus vulgaris cDNA clones responsive to water deficit: identification of a novel late embryogenesis abundant-like protein. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 393–405 10.1007/s00284-009-9552-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmenero-Flores J. M., Moreno L. P., Smith C., Covarrubias A. A. (1999). Pvlea-18, a member of a new late-embryogenesis-abundant protein family that accumulates during water stress and in the growing regions of well-irrigated bean seedlings. Plant Physiol. 120, 93–103 10.1093/pcp/pcr052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez P. G., Frankel N., Mazuch J., Balbo I., Iusem N., Fernie A. R., et al. (2013). ASR1 mediates glucose-hormone crosstalk by affecting sugar trafficking in tobacco plants. Plant Physiol. 161, 1486–1500 10.1104/pp.112.208199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J., Cai W. (2012). OsLEA3-2, an abiotic stress induced gene of rice plays a key role in salt and drought tolerante. PLoS ONE 7:e45117 10.1371/journal.pone.0045117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dure L., III (1993). Structural motifs in Lea proteins, in Plant Responses to Cellular Dehydration During Environmental Stress, eds Close T. J., Bray E. A. (Rockville, MD: The American Society of Plant Physiologists; ), 91–103 10.1104/pp.105.072967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dure L., III, Crouch M., Harada J., Ho T. H. D., Mundy J., Quatrano R., et al. (1989). Common amino acid sequence domains among the LEA proteins of higher plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 12, 475–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dure L., III, Greenway S. C., Galau G. A. (1981). Developmental biochemistry of cottonseed embryogenesis and germination: changing messenger ribonucleic acid populations as shown by in vitro and in vivo protein synthesis. Biochemistry 20, 4162–4168 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson S. K., Harryson P. (2011). Dehydrins: molecular biology, structure and function, in Plant Desiccation Tolerance, eds Lüttge U., Beck B., Bartels D. (Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; ), 289–305 10.1271/bbb.67.1832 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gai Y. P., Ji X. L., Lu W., Han X. J., Yang G. D., Zheng C. C. (2011). A novel late embryogenesis abundant like protein associated with chilling stress in Nicotiana tabacum cv. bright yellow-2 cell suspension culture. Mol. Cel. Proteom. 10:M111.010363. 10.1074/mcp.M111.010363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garay-Arroyo A., Colmenero-Flores J. M., Garciarrubio A., Covarrubias A. A. (2000). Highly hydrophilic proteins in prokaryotes and eukaryotes are common during conditions of water deficit. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5668–5674 10.1104/pp.001925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gepts P., Beavis W. D., Brummer S., Shoemaker R. C., Stalker H. T., Weeden N. F., et al. (2005). Legumes as a model plant family. genomics for food and feed report of the cross-legume advances through genomics conference. Plant Physiol. 137, 1228–1235 10.1104/pp.105.060871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goday A., Jensen A. B., Culianez-Macia F. A., Mar Alba M., Figueras M., Serratosa J., et al. (1994). The maize abscisic acid-responsive protein Rab17 is located in the nucleus and interacts with nuclear localization signals. Plant Cell 6, 351–360 10.1104/pp.110.158964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goormachtig S., Capoen W., Holsters M. (2004). Rhizobium infection: lessons from the versatile nodulation behaviour of water-tolerant legumes. Trends Plant Sci. 9, 518–522 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal K., Pinelli C., Maslen S. L., Rastogi R. K., Stephens E., Tunnacliffe A. (2005a). Dehydration-regulated processing of late embryogenesis abundant protein in a desiccation-tolerant nematode. FEBS Lett. 579, 4093–4098 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal K., Walton L. J., Tunnacliffe A. (2005b). LEA proteins prevent protein aggregation due to water stress. Biochem. J. 388, 151–157 10.1042/BJ20041931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelet J., Benamar A., Teyssier E., Avelange-Macherel M. H., Grunwald D., Macherel D. (2005). Identification in pea seed mitochondria of a late-embryogenesis abundant protein able to protect enzymes from drying. Plant Physiol. 137, 157–167 10.1104/pp.104.052480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hand S. C., Menze M. A., Toner M., Boswell L., Moore D. (2011). LEA proteins during water stress: not just for plants anymore. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 73, 115–134 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanin M., Brini F., Ebel C. H., Toda Y., Takeda S., Masmoudi K. (2011). Plant dehydrins and stress tolerance. versatile proteins for complex mechanisms. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1503–1509 10.4161/psb.6.10.17088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M. (2010). The multifunctionality of dehydrins. an overview. Plant Signal. Behav. 5, 503–508 10.1186/1471-2229-10-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M., Fujinaga M., Kuboi T. (2005). Metal binding by citrus dehydrin with histidine-rich domains. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2695–2703 10.1093/jxb/eri262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M., Shinoda Y., Tanaka Y., Kuboi T. (2009). DNA binding of citrus dehydrin promoted by zinc ion. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 532–541 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01947.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M., Wakasugi Y., Ikoma Y., Yano M., Ogawa K., Kuboi T. (1999). cDNA sequence and expression of a cold-responsive gene in Citrus unshiu. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63, 433–437 10.1073/pnas.0306154101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjoh K., Yoshimoto M., Joh T., Kajiwara T., Miyamoto T., Hatano S. (1995). Isolation and characterization of hardening-induced proteins in Chlorella vulgaris C-27: identification of late embryogenesis abundant proteins. Plant Cell Physiol. 36, 1421–1430 10.1007/s00497-006-0035-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde M., Daniel C., Lachapelle M., Allard F., Laliberte S., Sarhan F. (1995). Immunolocalization of freezing-tolerance-associated proteins in the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm of wheat crown tissues. Plant J. 8, 583–593 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing Y. C., Chen Z. Y., Shih M. D., Hsieh J. S., Chow T. Y. (1995). Unusual sequences of group 3 LEA mRNA inducible by maturation or drying in soybean seeds. Plant Mol. Biol. 29, 863–868 10.1093/pcp/pcq005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundertmark M., Dimova R., Lengefeld J., Seckler R., Hincha D. K. (2011). The intrinsically disordered late embryogenesis abundant protein LEA18 from Arabidopsis thaliana modulates membrane stability through binding and folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomem. 1808, 446–453 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundertmark M., Hincha D. K. (2008). LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genom. 9:118 10.1186/1471-2164-9-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundertmark M., Popova A. V., Rausch S., Seckler R., Hincha D. K. (2012). Influence of drying on the secondary structure of intrinsically disordered and globular proteins. Biochem. Biophy. Res. Com. 417, 122–128 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail A. M., Hall A. E., Close T. J. (1999). Purification and partial characterization of a dehydrin involved in chilling tolerance during seedling emergence of cowpea. Plant Physiol. 120, 237–244 10.1007/s004250050424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joh T., Honjoh K., Yoshimoto M., Funabashi J., Miyamoto T., Hatano S. (1995). Molecular cloning and expression of hardening-induced genes in Chlorella vulgaris C-27: the most abundant clone encodes a late embryogenesis abundant protein. Plant Cell Physiol. 36, 85–93 10.1007/s12038-011-9058-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi T., Patil K., Fitzpatrick M. R., Franklin L. D., Yao Q., Cook J. R., et al. (2012). Soybean Knowledge Base (SoyKB): a web resource for soybean translational genomics. BMC Genom. 13Suppl. 1:S15 10.1186/1471-2164-13-S1-S15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaiselvi K., Manickam A. (1999). Characterization of an axis-specific protein from mung bean expressed late during seed maturation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 37, 203–208 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kikawada T., Nakahara Y., Kanamori Y., Iwata K.-i., Watanabe M., McGee B., et al. (2006). Dehydration-induced expression of LEA proteins in an anhydrobiotic chironomid. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Com. 348, 56–61 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koag M. C., Fenton R. D., Wilkens S., Close T. J. (2003). The binding of maize DHN1 to lipid vesicles. Gain of structure and lipid specificity. Plant Physiol. 131, 309–316 10.1104/pp.011171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koag M. C., Wilkens S., Fenton R. D., Resnik J., Vo E., Close T. J. (2009). The K-segment of maize DHN1 mediates binding to anionic phospholipid vesicles and concomitant structural changes. Plant Physiol. 150, 1503–1514 10.1104/pp.109.136697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosová K., Vítámvás P., Prášil I. T. (2007). The role of dehydrins in plant response to cold. Biol. Plant. 51, 601–617 10.1002/pmic.200700259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le D. T., Nishiyama R., Watanabe Y., Tanaka M., Seki M., Ham le H., et al. (2012). Differential gene expression in soybean leaf tissues at late developmental stages under drought stress revealed by genome-wide transcriptome analysis. PLoS ONE 7:e49522 10.1371/journal.pone.0049522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libault M., Farmer A., Brechenmacher L., Drnevich J., Langley R. J., Bilgin D. D., et al. (2010a). Complete transcriptome of the soybean root hair cell, a single-cell model, and its alteration in response to Bradyrhizobium japonicum infection. Plant Physiol. 152, 541–552 10.1104/pp.109.148379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libault M., Farmer A., Joshi T., Takahashi K., Langley R. J., Franklin L. D., et al. (2010b). An integrated transcriptome atlas of the crop model Glycine max, and its use in comparative analyses in plants. Plant J. 63, 86–99 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04222.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisse T., Bartels D., Kalbitzer H. R., Jaenicke R. (1996). The recombinant dehydrin-like desiccation stress protein from the resurrection plant Craterostigma plantagineum displays no defined three-dimensional structure in its native state. Biol. Chem. 377, 555–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H., Peng P. H., Ko C. Y., Markhart A. H., Lin T. Y. (2012). Characterization of a novel Y2K-type dehydrin VrDhn1 from Vigna radiata. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 930–942 10.1093/pcp/pcs040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litts J. C., Colwell G. W., Chakerian R. L., Quatrano R. S. (1987). The nucleotide sequence of a cDNA clone encoding the wheat Em protein. Nucleic Acid Res. 15, 3607–3618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litts J. C., Colwell G. W., Chakerian R. L., Quatrano R. S. (1991). Sequence analysis of a functional member of the Em gene family from wheat. DNA Seq. 1, 263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Xu H., Zhang L., Zheng Y. (2011). Fe binding properties of two soybean (Glycine max L.) LEA4 proteins associated with antioxidant activity. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 994–1002 10.1093/pcp/pcr052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang L., Sun L., Pan J., Kong X., Zhang M., et al. (2013). ZmLEA3, a multifunctional group 3 LEA protein from maize Zea mays L, is involved in biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Physiol. 54, 944–959 10.1093/pcp/pct047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zheng Y. (2005). PM2, a group 3 LEA protein from soybean, and its 22-mer repeating region confer salt tolerance in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Com. 331, 325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Zheng Y., Zhang Y., Wang W., Li R. (2010). Soybean PM2 protein (LEA3) confers the tolerance of Escherichia coli and stabilization of enzyme activity under diverse stresses. Curr. Microbiol. 60, 373–378 10.1007/s00284-009-9552-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfre A. J., LaHatte G. A., Climer C. R., Marcotte W. R., Jr. (2009). Seed dehydration and the establishment of desiccation tolerance during seed maturation is altered in the Arabidopsis thaliana mutant atem6-1. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 243–253 10.1093/pcp/pcn185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfre A. J., Lanni L. M., Marcotte W. R., Jr. (2006). The Arabidopsis group 1 LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT protein ATEM6 is required for normal seed development. Plant Physiol. 140, 140–149 10.1104/pp.105.072967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskin L., Frankel N., Gudesblat G., Demergasso M. J., Pietrasanta L. I., Iusem N. D. (2007). Dimerization and DNA-binding of ASR1, a small hydrophilic protein abundant in plant tissues suffering from water loss. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Com. 352, 831–835 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marunde M. R., Samarajeewa D. A., Anderson J., Li S., Hand S. C., Menze M. A. (2013). Improved tolerance to salt and water stress in Drosophila melanogaster cells conferred by late embryogenesis abundant protein. J. Insect Physiol. 59, 377–386 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momma M., Kaneko S., Haraguchi K., Matsukura U. (2003). Peptide mapping and assessment of cryoprotective activity of 26/27-kDa dehydrin from soybean seeds. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 67, 1832–1835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Fonseca L. P., Covarrubias A. A. (2001). Downstream DNA sequences are required to modulate Pvlea-18 gene expression in response to dehydration. Plant Mol. Biol. 45, 501–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndong C., Danyluk J., Wilson K. E., Pocock T., Huner N. P. A., Sarhan F. (2002). Cold-regulated cereal chloroplast late embryogenesis abundant-like proteins. molecular characterization and functional analyses. Plant Physiol. 129, 1368–1381 10.1104/pp.001925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd G. E., Downie J. A. (2008). Coordinating nodule morphogenesis with rhizobial infection in legumes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 519–546 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvera-Carrillo Y., Campos F., Reyes J. L., Garciarrubio A., Covarrubias A. A. (2010). Functional analysis of the group 4 late embryogenesis abundant proteins reveals their relevance in the adaptive response during water deficit in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154, 373–390 10.1104/pp.110.158964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvera-Carrillo Y., Reyes J. L., Covarrubias A. A. (2011). Late Embryogenesis Abundant proteins: versatile players in the plant adaptation to water limiting environments. Plant Signal. Behav. 64, 1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popova A. V., Hundertmark M., Seckler R., Hincha D. K. (2011). Structural transitions in the intrinsically disordered plant dehydration stress protein LEA7 upon drying are modulated by the presence of membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 1879–1887 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcel R., Azcón R., Ruiz-Lozano J. D. (2005). Evaluation of the role of genes encoding for dehydrin proteins (LEA D-11) during drought stress in arbuscular mycorrhizal Glycine max and Lactuca sativa plants. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 1933–1942 10.1093/jxb/eri188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhakainen T., Hess M. W., Makela P., Svensson J., Heino P., Palva E. T. (2004). Overexpression of multiple dehydrin genes enhances tolerance to freezing stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 54, 743–753 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000040903.66496.a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan V., Kamalay J. C. (1993). Expression of two cloned mRNA sequences during development and germination of spores of the sensitive fern, Onoclea sensibilis L. Planta 189, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J. L., Campos F., Wei H., Arora R., Yang Y., Karlson D. T., et al. (2008). Functional dissection of hydrophilins during in vitro freeze protection. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 1781–1790 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J. L., Rodrigo M. J., Colmenero-Flores J. M., Gil J. V., Garay-Arroyo A., Campos F., et al. (2005). Hydrophilins from distant organisms can protect enzymatic activities from water limitation effects in vitro. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 709–718 [Google Scholar]

- Riera M., Figueras M., López C., Goday A., Pages M. (2004). Protein kinase CK2 modulates developmental functions of the abscisic acid responsive protein Rab17 from maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9879–9884 10.1073/pnas.0306154101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorat T. (2006). Plant dehydrins - Tissue localization, structure and function. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 11, 536–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra L., Svensson J., Carballo V., Izmendi D., Welin B., Vidal S. (2006). A dehydrin gene in Physcomitrella patens is required for salt and osmotic stress tolerance. Plant J. 45, 237–249 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02603.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severin A. J., Woody J. L., Bolon Y. T., Joseph B., Diers B. W., Farmer A. D., et al. (2010). RNA-Seq Atlas of Glycine max: a guide to the soybean transcriptome. BMC Plant Biol. 10:160 10.1186/1471-2229-10-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheoran I. S., Sproule K. A., Olson D. J. H., Ross A. R. S., Sawhney V. K. (2006). Proteome profile and functional classification of proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana (Landsberg erecta) mature pollen. Sex. Plant Reprod. 19, 185–196 [Google Scholar]

- Shih M. D., Hsieh T. Y., Jian W. T., Wu M. T., Yang S. J., Hoekstra F. A., et al. (2012). Functional studies of soybean (Glycine max L.) seed LEA proteins GmPM6, GmPM11, and GmPM30 by CD and FTIR spectroscopy. Plant Sci. 196, 152–159 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih M. D., Hsieh T. Y., Lin T. P., Hsing Y. I. C., Hoekstra F. A. (2010). Characterization of two soybean (Glycine max L.) LEA IV proteins by circular dichroism and Fourier transform infrared spectrometry. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 395–407 10.1093/pcp/pcq005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih M. D., Lin S. C., Hsieh J. S., Tsou C. H., Chow T. Y., Lin T. P., et al. (2004). Gene cloning and characterization of a soybean (Glycine max L.) LEA protein, GmPM16. Plant Mol. Biol. 56, 689–703 10.1007/s11103-004-4680-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulages J. L., Kim K., Arrese E. L., Walters C., Cushman J. C. (2003). Conformation of a group 2 late embryogenesis abundant protein from soybean. evidence of poly (L-proline)-type II structure. Plant Physiol. 131, 963–975 10.1104/pp.015891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulages J. L., Kim K., Walters C., Cushman J. C. (2002). Temperature-induced extended helix/random coil transitions in a group 1 late embryogenesis-abundant protein from soybean. Plant Physiol. 128, 822–832 10.1104/pp.010521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy R. A. P., Aalen R. B. (1998). Identification of sequence homology between the internal hydrophilic repeated motifs of Group 1 late-embryogenesis-abundant proteins in plants and hydrophilic repeats of the general stress protein GsiB of Bacillus subtilis. Planta 206, 476–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L., Zhao C. Z., Bi Y. P., Wan S. B., Xia H., Wang X. J. (2011). Isolation and expression analysis of LEA genes in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). J. Biosci. 36, 223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thalhammer A., Hundertmark M., Popova A. V., Seckler R., Hincha D. K. (2010). Interaction of two intrinsically disordered plant stress proteins (COR15A and COR15B) with lipid membranes in the dry state. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798, 1812–1820 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolleter D., Hincha D. K., Macherel D. (2010). A mitochondrial late embryogenesis abundant protein stabilizes model membranes in the dry state. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798, 1926–1933 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney R. K., Chen W., Li Y., Bharti A. K., Saxena R. K., Schlueter J. A., et al. (2012). Draft genome sequence of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan), an orphan legume crop of resource-poor farmers. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, Aì83–Aì89 10.1038/nbt.2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney R. K., Song C., Saxena R. K., Azam S., Yu S., Sharpe A. G., et al. (2013). Draft genome sequence of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provides a resource for trait improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, Aì240–Aì246 10.1038/nbt.2491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicient C. M., Hull G., Guilleminot J., Devic M., Delseny M. (2000). Differential expression of the Arabidopsis genes coding for Em-like proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 51, 1211–1220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Meng B., Chen W., Ge X., Liu S., Yu J. (2007). A proteomic study on postdiapaused embryonic development of brine shrimp (Artemia franciscana). Proteomics 7, 3580–3591 10.1002/pmic.200700259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitsitt M. S., Collins R. G., Mullet J. E. (1997). Modulation of dehydration tolerance in soybean seedlings (Dehydrin Mat1 is induced by dehydration but not by abscisic acid). Plant Physiol. 114, 917–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkers W. F., McCready S., Brandt W. F., Lindsey G. G., Hoekstra F. A. (2001). Isolation and characterization of a D-7 LEA protein from pollen that stabilizes glasses in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1544, 196–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., McKinlay C., Hocart C. H., Djordjevic M. A. (2006). The Medicago truncatula small protein proteome and peptidome. J. Proteome Res. 5, 3355–3367 10.1021/pr060336t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]