Summary

Absence of phagocyte NADPH oxidase (NOX2) activity causes chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a primary immunodeficiency characterized by recurrent bacterial infections. In contrast to this innate immune deficit, CGD patients and animal models display predisposition to autoimmune disease and enhanced response to H. pylori and influenza infection. These data imply an altered, perhaps augmented, adaptive immune response in CGD. Previous data demonstrated functional NOX2 expression in T cells, and the goal was to determine if NOX2-deficient T cells are inherently altered in their responses. Activation of purified naive CD4+ T cells from NOX2-deficient mice led to augmented IFN-γ and diminished IL-4 production and an increased ratio of expression of the TH1-specific transcription factor T-bet versus the TH2-specfic transcription factor GATA-3, consistent with a TH1 skewing of naïve T cells. Selective inhibition of TCR-induced STAT5 phosphorylation was identified as a potential mechanism for skewed T helper differentiation. Exposure to anti-oxidants inhibited, while pro-oxidants augmented TH2 cytokine secretion and STAT5 phosphorylation, supporting the redox dependence of these signaling changes. These data suggest that TCR-induced ROS generation from NOX2 activation can regulate the adaptive immune response in a T cell inherent fashion, and propose a possible role for redox signaling in T helper differentiation.

Keywords: chronic granulomatous disease, NADPH oxidase, reactive oxygen species, STAT5

Introduction

The NOX family of NADPH oxidases [1] is a group of transmembrane proteins that intentionally generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), and have been shown to play important roles in cell signaling and are involved in the cellular response to a variety of inflammatory stimuli. The phagocyte-type oxidase, of which NOX2 is the catalytic subunit, is the prototypic member of this family. Mutations or deletions that affect subunits of this complex cause chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), an immunodeficiency syndrome characterized by the impaired ability of phagocytic cells to kill engulfed microorganisms, primarily catalase positive organisms, such as Aspergillus and Staphyloccal species [2, 3].

In contrast to the defects in innate immunity, CGD patients are prone to develop autoimmune phenomena, such as Crohns-like disease, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis or lupus-related syndromes [4-6]. In addition to similar sensitivity to autoimmune phenomena, [7, 8] animal models of CGD also display a heightened response to certain infectious agents including Cryptococcus neoformans, influenza virus, and Helicobacter pylori [9-11]. Thus, immunodeficiency in CGD is sometimes associated with enhanced inflammation and immune responses.

The T cell response observed in CGD mice upon influenza or Cryptococcus infection was characterized by a heightened macrophage-driven TH1 response [9, 10] while in other systems NOX deficiency correlated with a heightened TH17 response [12-14]. Nevertheless, it is clear that NOX2 plays a role in shaping the adaptive immune response. One model suggests that oxidase deficiency in antigen presenting cells (APC) alters their capability to activate T cells, instructing naive T cells down a certain differentiation pathway during priming [13, 15, 16]. In contrast to this “APC instructive model”, the intrinsic expression of NOX2 in T cells themselves may also play a role in lineage fate decisions. Peripheral T cells have been shown to express a functional phagocyte NADPH oxidase [17-19]. In support of an effect of ROS on T cell differentiation, previous studies have demonstrated that treating T cells with antioxidants promoted a TH1 response with increased IFN-γ and decreased IL-4 [20, 21] while pro-oxidants biased them toward a TH2 phenotype, resulting increased amounts of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 [22]. Taken together, these findings suggest a redox dependent modulation of T helper responses. However, the mechanism(s) by which oxidase/ROS deficiency leads to phenotypic changes in T cell activity and function remains unresolved.

Several factors impact the decision of naive CD4+ T cells to develop down a particular differentiation pathway. Master regulator transcription factors, e.g., GATA-3 (TH2), T-bet (TH1) and ROR-γt (TH17) regulate key gene loci, in turn promoting or repressing expression of cytokines and receptors that determine the direction of differentiation [23, 24]. Regulatory loops exist such that the cytokines can further augment or inhibit expression of these master regulators, which then feedback and inhibit expression of other master regulators. For example, the prototypical TH2 cytokine IL-4 can induce expression of GATA-3. GATA-3 binds and helps open the Il4 locus (enhancing IL-4 production) and also inhibits expression of cytokines (IFN-γ) and receptors (IL-12Rβ) that promote TH1 differentiation. The signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family of transcription factors regulates many of the downstream signaling effects of cytokines in T helper development. The transcription factors STAT4 and STAT1, activated by IL-12 and IFN-γ respectively, induce the expression of T-bet, while IL-4 mediated STAT6 activation upregulates GATA-3 expression [24]. STAT5 is also an important player in T helper development. IL-2 mediated activation of STAT5 stimulates the proliferation and survival of T cells, but is also needed for optimal induction of a TH2 response [25]. Recent studies have identified IL-2 dependent opening of the Il4 locus and upregulated expression of the IL-4Rα on T cells in a STAT5-dependent fashion after TCR ligation [26-28].

The goal of this study was to determine whether and how the phagocyte oxidase functions in naive T cells to modulate T helper differentiation. The results support previous data[9, 10, 17], in that NOX2(−/−), naive CD4+ T cells are innately more TH1 skewed than their wild type counterparts. These T cells secreted increased IFN-γ, but decreased IL-4 in response to anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation. There were also selective decreases in GATA-3 and the phosphorylation of STAT5, with decreased Il4 gene expression which suggested a mechanism for decreased TH2 conditions. Finally, treatment with antioxidants or adding back ROS with pro-oxidants recapitulated these selective changes in TCR-induced transcription factor activation. Taken together, these findings suggest that during priming, TCR-induced ROS generation from NOX2 activation selectively promotes STAT5 phosphorylation and downstream TH2 development in CD4+ T cells.

Results

The expression of NOX2 in T cell development

While the absence of NOX2 has been shown to affect T cell function, NOX2 expression during T cell development has not been measured. Relatively low levels of NOX2 mRNA were found in immature T cells from the thymus of C57BL/6 mice (Supplemental Figure 1A), but higher levels were found in resting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of the spleen and lymph nodes. Expression of NOX2 in the thymus suggests that it may play a role in T cells as early as thymocyte development. However, the higher expression levels in T cells from the spleen and lymph nodes may indicate that NOX2 generated ROS play more of a role in mature T cells than in developing thymocytes. In wild type C57BL/6 and oxidase deficient NOX2 knockout mice, flow cytometric analysis of the thymus (Supplemental Figure 1B) and spleen (Supplemental Figure 1C, D) demonstrated no detectable differences in lymphocyte composition of these organs, including naïve, effector, and memory T cell subsets. Total cellularity as well as cell viability of the spleen, thymus and lymph nodes between wild type and oxidase deficient mice were unchanged.

Oxidase deficient T cells are more TH1 skewed than their wild type counterparts

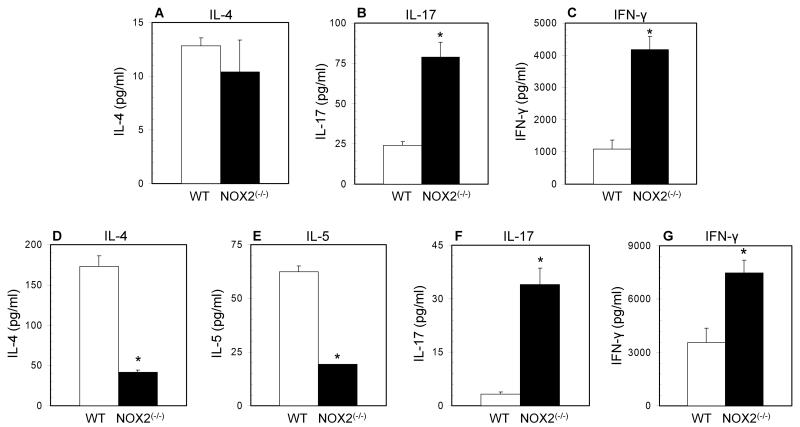

To determine if there was intrinsic TH1 skewing of the oxidase deficient adaptive immune system during primary activation, total resting splenocytes from wild type and NOX2-deficient mice were stimulated for 72 hours on immobilized anti-CD3 and cytokine production was assessed by ELISA. Cell supernatants from oxidase deficient splenocytes contained decreased amounts of IL-4 but increased concentrations of both IL-17 and IFN-γ (Figure 1A-C). Because total spleen includes both antigen presenting cells as well as memory T cells, naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated from NOX2(−/−) mice, and these cells produced significantly increased levels of IFN-γ and IL-17, but significantly decreased levels of IL-4 and IL-5 (Figure 1D-F). After activation, no differences were observed in cell yield or cell viability (data not shown). Thus, NOX2-deficient naive CD4+ T cells may be inherently skewed away from a TH2 phenotype as early as during primary activation.

Figure 1. Enhanced inflammatory cytokine and decreased TH2 cytokine production from oxidase deficient T cells.

Total splenocytes (A-C) and naïve CD4+ T cells (D-G) from wild type (open bars) and NOX2-deficient (closed bars) mice were cultured for 48 to 72 hours on immobilized anti-CD3 for total splenocytes, and immobilized anti-CD3 with soluble anti-CD28 for CD4+ T cells. Supernatants were collected for analysis by ELISA. (n = 4 separate experiments, * significantly different from wild type; p<0.05 calculated by paired T test).

Oxidase deficient naïve T cells have decreased GATA-3 during primary activation

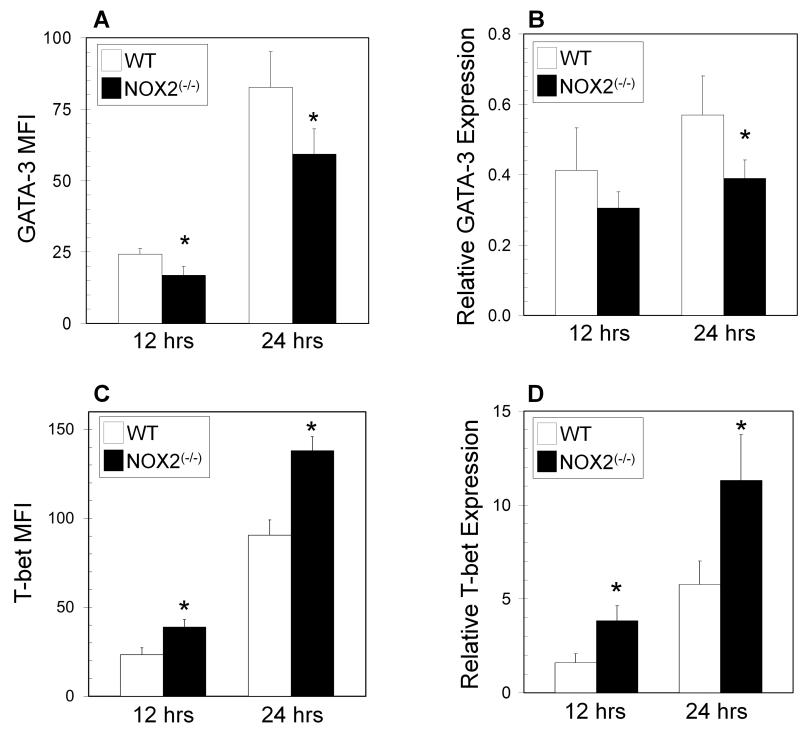

Expression of the lineage-specifying transcription factors (T-bet, GATA-3, and ROR-γt for TH1, TH2, and TH 17 cells, respectively) regulates the fate of activated helper CD4+ T effectors. Upon TCR stimulation, NOX2-deficient T cells had significantly decreased levels of GATA-3 protein by intracellular staining (Figure 2A), whereas T-bet levels were significantly increased (Figure 2C). When gene expression was examined, NOX2-deficient T cells also had decreased mRNA expression of GATA-3 at 24 hours post stimulation (Figure 2B), while T-bet expression was significantly increased at both 12 and 24 hours after activation (Figure 2D). Expression of the T-bet: GATA-3 ratio is often used to indicate CD4+ T cell differentiation [23, 29, 30], and the ratio of T-bet to GATA-3 at both protein and mRNA levels were significantly increased, further reflecting changes in T helper skewing (Supplemental Figure 2). No significant differences were observed in ROR-γt expression (not shown). These data suggest that oxidase deficient T cells have altered expression of master regulator transcription factors during early activation through TCR stimulation.

Figure 2. GATA-3 and T-bet levels in oxidase deficient CD4+ T cells.

Naïve CD4+ T cells from wild type (WT) (open bars) and NOX2-deficient (NOX2(−/−)) (closed bars) mice were cultured for 12 and 24 hours on immobilized anti-CD3 with soluble anti-CD28. Cells were harvested and underwent intracellular staining for GATA-3 (A), and T-bet (C) and were analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the Methods. The data are expressed as the increase in mean fluorescence intensity after stimulation +/− SEM. (n = 5 separate experiments, * significantly different from wild type; p<0.05 calculated by Wilcoxon signed rank test). GATA-3 (B) and T-bet (D) mRNA expression was assessed in naïve CD4+ T cells by qPCR in wild type (open bars) and NOX2-deficient (closed bars) mice. These data are expressed as the expression of the indicated mRNA relative to control HPRT mRNA (triplicate wells from 2 separate experiments, * significantly different from wild type; p<0.05 calculated by Wilcoxon signed rank test).

Alterations in phosphorylated STAT proteins in oxidase deficient T cells

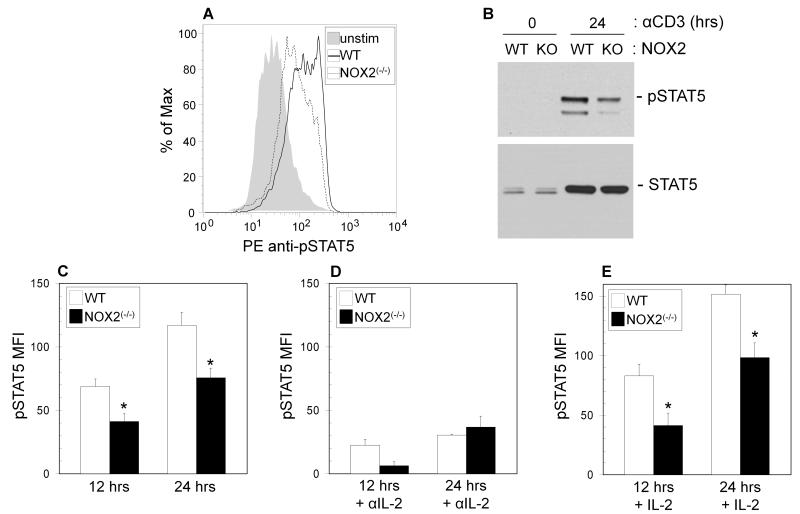

Signaling through cytokine receptors, activating JAK-STAT signaling pathways are critical for control of T helper differentiation [24, 31]. After primary activation, the levels of phosphorylated STAT1, STAT3, and STAT4 were found to be unchanged between wild type and NOX2-deficient T cells (Supplemental Figure 3). On the other hand, phosphorylation of STAT5 was found to be decreased nearly two fold in NOX2-deficient T cells as compared to wild type controls by intracellular staining at 12 and 24 hours after activation (Figure 3A & C), and these data were confirmed by Western blot (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Decreased phosphorylated STAT5 in NOX2-deficient CD4+ T cells.

Naïve CD4+ T cells from wild type (WT) (open bars) and NOX2-deficient mice (NOX2(−/−)) (closed bars) were cultured for 12 and 24 hours on immobilized anti-CD3 with soluble anti-CD28 (A, C), or were stimulated in the presence of 10 μg/ml anti-IL-2 (D) or 0.25 U/ml IL-2 (E). Cells were harvested and underwent intracellular staining for pSTAT5 and were analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the Methods (C-E), or cells were harvested, lysed and protein was extracted for Western Blot anaylsis (B). (A) A representative staining profile for pSTAT5. (B) A Western blot for pSTAT5 in wild type (WT) and NOX2-deficient (KO) naïve CD4+ T cells cultured for 0 or 24 hours with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. The flow cytometry data are expressed as the increase in mean fluorescence intensity after stimulation +/− SEM. (n = 5 separate experiments, * significantly different from wild type; p<0.05 calculated by Wilcoxon signed rank test).

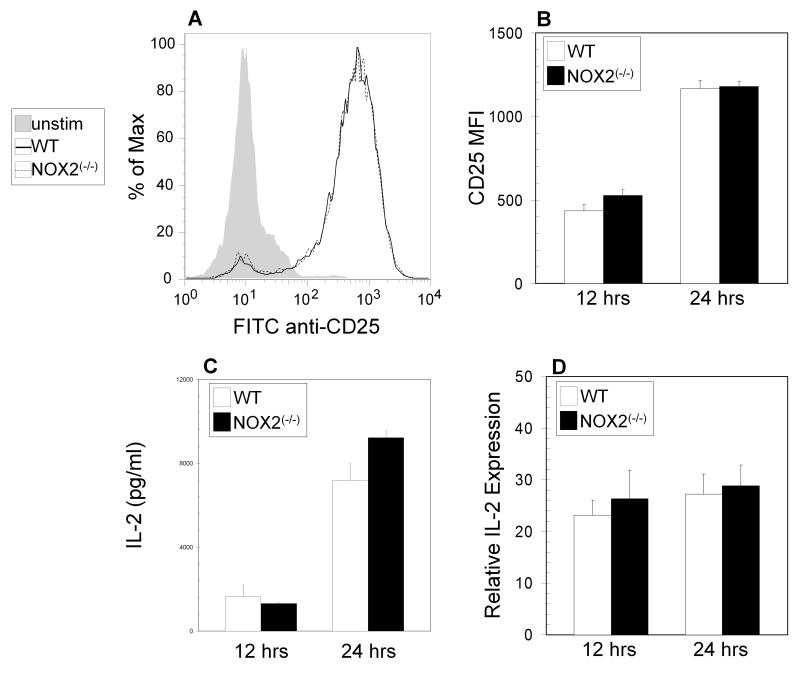

TCR stimulated STAT5 phosphorylation and subsequent TH2 development has been proposed to be IL-2 dependent [25], and stimulation in the presence of a neutralizing antibody to IL-2 led to strong decreases in STAT5 phosphorylation in both wild type and oxidase deficient cells (Figure 3D) as compared to stimulation in the absence of antibody (Figure 3C). Induction of IL-2Rα (CD25) surface expression and IL-2 protein and mRNA levels after TCR stimulation of naïve T cells were the same in wild type and NOX2-deficient mice (Figure 4A-D). Furthermore, addition of exogenous IL-2 during activation did not increase the levels of phosphorylated STAT5 (Figure 3E) in NOX2-deficient T cells to those in wild type T cells, suggesting that changes in STAT5 phosphorylation are not a result of decreased IL-2 production or decreased sensitivity to IL-2. Thus, NOX2-deficient naive CD4+ T cells have a defect in TCR-stimulated STAT5 activation, which may subsequently affect downstream TH2 differentiation early during activation.

Figure 4. Lack of changes in IL-2/IL-2R expression in NOX2-deficient CD4+ T cells.

(A-B) Naïve CD4+ T cells from wild type (open bars) and NOX2-deficient (NOX2(−/−)) (closed bars) mice were cultured for 12 and 24 hours on immobilized anti-CD3 with soluble anti-CD28. Cells were harvested and surface staining for CD25 was analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) shows a representative staining profile, and in (B) the data are expressed as the increase in mean fluorescence intensity after stimulation +/− SEM (n = 5 separate experiments). (C) Supernatants from wild type (open bars) and NOX2-deficient (NOX2(−/−)) (closed bars) cells stimulated as in (B) were collected for analysis by ELISA (triplicate wells from 2 separate experiments). (D) mRNA from wild type (open bars) and NOX2-deficient (closed bars) cells stimulated as in (B) was extracted for qPCR analysis for IL-2 expression. qPCR data are expressed as the expression of the indicated mRNA relative to control HPRT mRNA (triplicate wells from 2 separate experiments,).

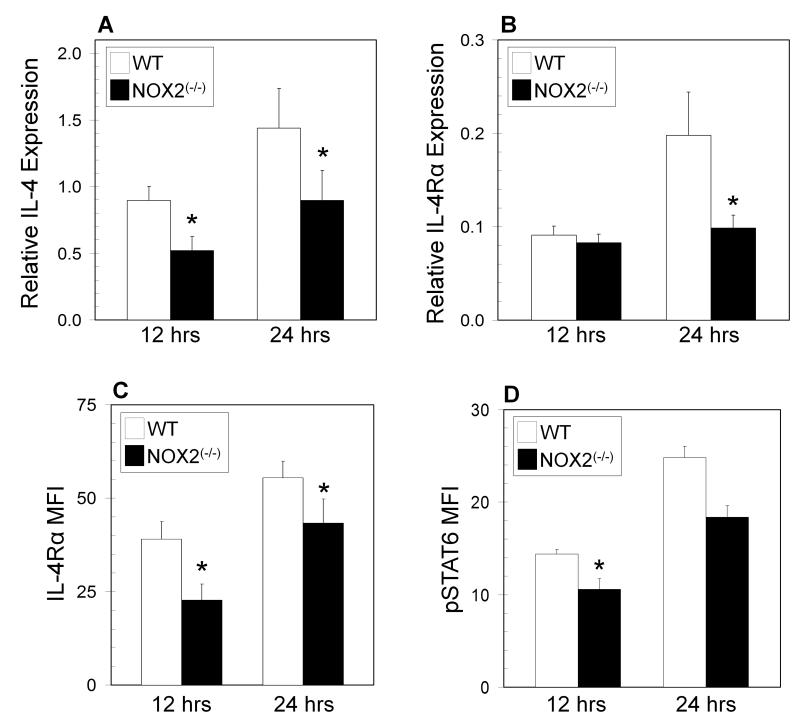

Decreased IL-4 and IL-4Rα expression in NOX2 deficient T cells

The model of STAT5 and GATA-3 regulation of T helper development suggests that these transcription factors facilitate the expression of both the Il4 and Il4rα genes. PCR analysis also found decreases in Il4 and Il4rα mRNA expression in NOX2-deficient T cells (Figure 5A,B). Surface expression of IL-4Rα was also downregulated in the absence of NOX2 (Figure 5C). Modestly decreased phosphorylated STAT6 levels were also observed in NOX2-deficient T cells (Figure 5D), likely as a consequence of reduced IL-4 production. In an attempt to bypass TH1 skewing of NOX2-deficient T cells, naïve cells were activated under TH2 skewing conditions. Consistent with normal TH2 lineage commitment, STAT6 phosphorylation and GATA3 expression (Supplemental Figure 4A, B) were greatly enhanced under TH2 skewing conditions, but there were no detectable differences observed between wild type and NOX2-deficient cells. However, TH2 skewing of NOX2-deficient T cells during primary activation did not increase the expression of IL-4 to the levels seen in wild type T cells (Supplemental Figure 4C), suggesting that defects in the opening of the Il4 locus are still present in oxidase deficient T cells, potentially due to alterations in STAT5 signaling.

Figure 5. Decreased IL-4 and IL-4Rα expression in NOX2-deficient CD4+ T cells.

Naïve CD4+ T cells from wild type (WT) (open bars) and NOX2-deficient (NOX2(−/−)) (closed bars) mice were cultured for 12 and 24 hours on immobilized anti-CD3 with soluble anti-CD28. mRNA was extracted for qPCR analysis for IL-4 (A) and IL-4Rα (B) expression. qPCR data are expressed as the expression of the indicated mRNA relative to control HPRT mRNA (triplicate wells from 2 separate experiments,). Following incubation, cells were harvested and underwent surface staining for IL-4Rα (C) or intracellular staining for pSTAT6 (D) and were analyzed by flow cytometry. The data are expressed as the increase in mean fluorescence intensity after stimulation +/− SEM (n = 3 separate experiments, * significantly different from wild type; p<0.05 calculated by paired T test).

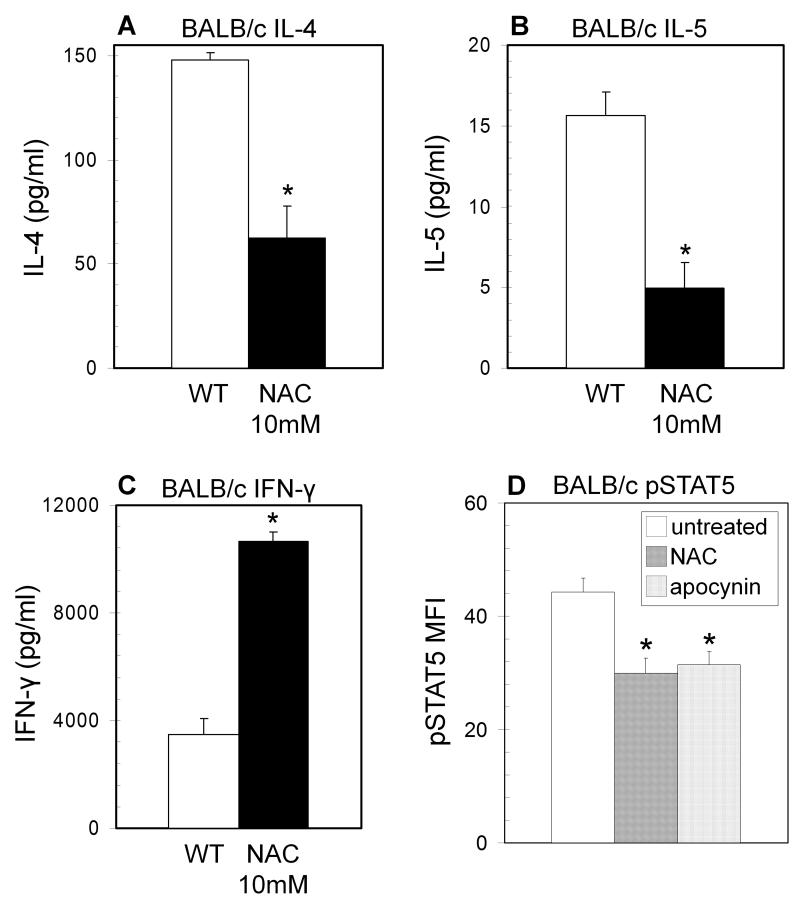

Enhanced TH1 phenotype in BALB/c T cells treated with antioxidants

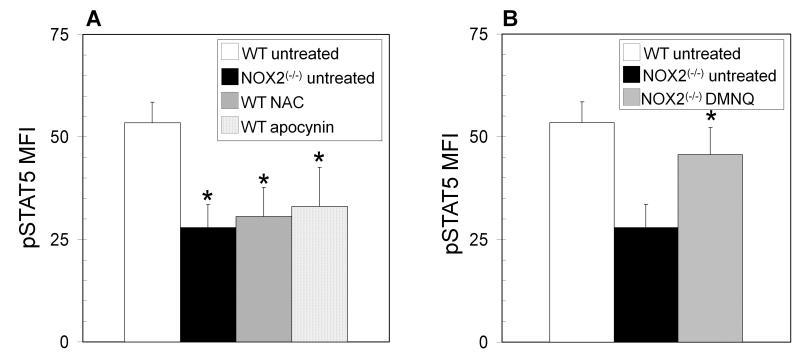

To consider the overall effect of redox signaling on T helper differentiation, CD4+ T cell blasts from BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence or absence of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC). BALB/c T cells preferentially follow a TH2 differentiation pathway, and treatment of BALB/c CD4+ T cell blasts with 10 mM NAC increased TH1 cytokine production and decreased TH2 cytokine production as compared to untreated controls (Figure 6A-C). BALB/c T cells treated with NAC also showed decreased phosphorylated STAT5 (Figure 6D), implicating oxidative signaling as a possible factor in T helper differentiation. Incubation with apocynin, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase activity, also significantly inhibited STAT5 phosphorylation (Figure 6D), implicating NOX2 in the oxidative regulation of STAT5. Antioxidants were also shown to have similar effects on STAT5 phosphorylation in T cells from C57BL/6 mice (Figure 7A). Furthermore, adding back ROS in the form of superoxide generated by treatment with DMNQ enhanced STAT5 phosphorylation in NOX2-deficient cells close to that observed in T cells from wild type mice (Figure 7B).

Figure 6. Antioxidants inhibit TH2 development in BALB/c T cells.

(A-C) CD4+ T cell blasts from BALB/c mice were cultured and restimulated on immobilized anti-CD3 in the presence of 10 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (closed bars). Supernatants were collected after 8 hours of restimulation for ELISA (n = 4 separate experiments, * Significantly different from wild type; p<0.05 calculated by paired T test). (D) BALB/c naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured on immobilized anti-CD3 with soluble anti-CD28 in the absence (open bars) or presence of NAC (10mM) (hatched bars) or the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin (100μM) (dotted bars) for 12 hours. Following incubation the cells underwent intracellular staining for pSTAT5 and were analyzed by flow cytometry. The data are expressed as the increase in mean fluorescence intensity after stimulation +/− SEM (n = 3 separate experiments, * significantly different from wild type; p<0.05 calculated by paired T test).

Figure 7. Oxidative regulation of STAT5 phosphorylation.

(A) naïve CD4+ T cells from wild type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were cultured in the absence (open bars) or presence of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (10mM) (hatched bars) or the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin (100 μM) (dotted bars) for 12 hours, and compared to naïve CD4+ T cells from NOX2-deficient (NOX2(−/−)) mice (solid bars). (B) Naïve CD4+ T cells from NOX2-deficient mice were cultured in the absence (closed bars) or presence of 1 μM of the pro-oxidant 2,3-Dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (DMNQ) (grey bars) for 12 hours, and compared to naïve CD4+ T cells from wild type mice (open bars). Following incubation the cells underwent intracellular staining for pSTAT5 and were analyzed by flow cytometry. The data are expressed as the increase in mean fluorescence intensity after stimulation +/− SEM (n = 3 separate experiments, * significantly different from untreated wild type; p<0.05 calculated by paired T test).

Discussion

The decision of naive T cells to differentiate into a particular helper subset is impacted by many different elements including signal strength, the local cytokine environment, the interaction of costimulatory molecules and the balance of downstream signaling cascades. The regulation of signaling in T helper development by changes in redox balance or oxidative stress in the adaptive immune system is not well understood. The results of this report demonstrate that the loss of NOX2-generated ROS in T cells promotes the polarization of naïve CD4+ T cells toward a TH1 phenotype during primary activation. Previous studies have demonstrated that antioxidants (selenium and α-tocopherol (vitamin E)) skew T cells toward a TH1 response [20, 21], while exposure to the pro-oxidant DMNQ biased CD4+ T cells toward TH2 phenotype [13, 22]. Furthermore, a recent study identified alterations in NOX2-deficient CD8+ T cells that promoted autoimmunity on a NOD background[18]. However, the mechanisms involved in these changes have not been explored. The current results identify decreases in GATA-3 and STAT5 phosphorylation as potential redox-dependent targets of NOX2-derived ROS during T cell activation and mechanisms for oxidant-mediated regulation of T helper differentiation.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that T cells express a functional NOX2 [17, 19], and its deficiency has been shown to alter the inherent function and survival of these cells [19, 32-35]. However, these reports have used T cell blasts or populations that included memory T cells, allowing for the possibility that instruction of these T cells by previous antigen experience or the presence of APCs could skew their subsequent response. Thus in the current study, purified naïve T cells were activated through anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, independent of APCs to limit the possibility of any extrinsic instruction. This does not eliminate that naïve T cells may have experienced a different environment in the absence of NOX2, during thymic selection or in non-reactive secondary lymphoid tissue prior to encountering antigen. However, there are no significant differences in thymic or splenic subsets in NOX2-knockout mice and NOX2-deficient naïve T cells do not exhibit basal differences in activation markers, phosphorylation of different STATs, or levels of lineage-specifying transcription factors. Thus, we propose that the changes in STAT5 and GATA-3 are inherent to NOX2-deficient T cells and dependent on changes in TCR-stimulated activation.

In previous studies, low antigen concentration or signal strength during TCR stimulation promoted TH2 development, and increasing the strength of TCR stimulation inhibited the associated increases in GATA-3 and phospho-STAT5, consequently promoting TH1 development [27, 36]. These studies suggested that TCR signals independently induced GATA-3 and STAT5 to open the Il4 locus and promote TH2 development [36, 37]. TCR signaling has been proposed to directly activate STAT5 phosphorylation [38], and the current results suggest that NOX2 deficiency is not altering production of IL-2 or upregulation of the IL-2Rα. Based on these observations, decreased STAT5 phosphorylation may be associated with lack of TCR-induced generation of ROS, which affects proximal IL-2R signaling.

Under conditions of increased antigen stimulation, co-incubation with a MEK inhibitor reversed the pro-TH1 effects on T helper differentiation, allowing increases in GATA-3 and phosphorylated STAT5 [27]. These data suggest increased ERK activation would inhibit TH2 development. Previous data in NOX2 deficient T cells as well as those cells treated with antioxidants observed increased TCR-induced MEK/ERK activation [17, 32], suggesting that NOX2/ROS dependent alterations in MEK/ERK signaling in T cells may inhibit TH2 development. Possible direct targets of NOX2 which may directly regulate STAT5 and the ERK signaling pathway are the oxidation sensitive protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) SHP-1 and SHP-2 PTPs [39-41].

The data suggest that NOX2-derived ROS selectively regulate STAT5 activation in TCR stimulated naïve T cells, which in turn affects the TH1/TH2 balance. It was unexpected that phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT4 were not augmented in the TH1 skewed NOX2-deficient T cells, but only early time points after activation were examined and T-bet mRNA and protein expression were clearly upregulated, suggesting that the T cells were pushed towards a TH1 phenotype. Decreases in GATA-3 protein levels in NOX2-deficient T cells are likely contributing to the increased T-bet expression in addition to its effects on IL-4 expression. Because the two master regulators have opposing actions, data are often expressed as the ratio of their expression (T-bet: GATA-3) [23, 29, 30, 42]. Previous studies found 3-4 fold differences in the T-bet: GATA-3 ratio during primary activation, when comparing TH1 versus TH2 skewing conditions [29, 30]. In the current study, under neutral, non-skewing conditions, 2-3 fold differences in the T-bet: GATA-3 ratios for both mRNA and protein were measured when comparing wild type and NOX-2 deficient T cells. Thus, small changes in the relative levels of T-bet and GATA-3 can be amplified into biologically significant changes during T helper development.

Although not directly tested in this study, decreased STAT5 phosphorylation in NOX2-deficient T cells may contribute to phenotypic changes observed in immune cells from both CGD patients and animal models of this disease. The association of CGD with autoimmune/rheumatologic disorders and the development of autoimmune arthritis in animal models could be due to an enhanced TH1 or TH17-mediated responses depending on the stimuli and immune microenvironment [12-14]. Recent studies have shown that STAT3 and STAT5 competitively bind to multiple common sites across the Il17 locus [43]. Thus, decreased phospho-STAT5 levels may allow for increased STAT3 binding to the Il17 locus, increasing the expression of IL-17. Furthermore, reports suggest diminished induction of T regulatory cells associated with CGD [12] and oxidase derived ROS has been shown to be involved in direct Treg mediated suppression of effector T cells [44]. STAT5 can induce the expression of the Treg transcription factor Foxp3 and decreased STAT5 would then inhibit Treg function or development. Additionally, decreased STAT5 activation may play a role in defects in survival in NOX2-deficient T cells. There is an association of CGD with decreased memory T cells and B cells [45, 46] and, in vitro, oxidase deficient T cells demonstrate decreased survival that could only be partially rescued by IL-7 [35]. Taken together, these observations and the results of this report suggest the importance of NADPH oxidase mediated activation of STAT5 in T cells.

The exact mechanisms behind the changes in the adaptive immune response observed in patients with CGD and animal models of the disease are still unresolved. However, one potential mechanism may involve inherent changes in helper T cell skewing and the data here have identified decreased GATA-3 expression and selective inhibition of TCR-induced STAT5 phosphorylation as potential mechanisms for skewed T helper differentiation in oxidase deficient naive T cells. Although their induction is most likely through separate downstream pathways, both GATA-3 and STAT5 signaling can be initially activated by TCR ligation. This study suggests that this involves NOX2, and proposes that in addition to alterations in the instruction of T cells by APC, T cells themselves are inherently altered as a result of oxidase deficiency. Thus, it is likely the combination of changes in both T cells and APC that result in previously reported alterations in the adaptive immune response in CGD.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 (stock # 000664), NOX2 deficient B6.129S6-Cybbtm1Din (stock # 002365), and BALB/c (stock # 000651) mice aged 4-6 weeks old were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. NOX2-deficient B6.129S6-Cybbtm1Din mice have been backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background and are maintained on a standard inbred strain by Jackson Laboratories. Animal care and all experimental procedures were performed in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee procedures approved at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Cell preparation and Negative Selection

Naive CD4+ T lymphocytes were prepared from spleens and lymph nodes by immunomagnetic depletion using a cocktail of antibodies against CD8 and B220 at 5 μg/ml (53-6.7 and RA3-6B2; eBioscience) and CD44 at 0.1 μg/ml (IM7; BD Pharmingen). Antibody-coated cells were removed by exposure to a magnetic field following incubation with BioMag goat anti-rat IgG conjugated magnetic beads (Qiagen) as described by the supplier. Purity (> 97%), as well as cell viability were assessed by flow cytometry (Supplemental Figures 5 and 6).

In vitro culture of T cells

Naive CD4+ T cells or total splenocytes were activated at 2 × 106 cells/ml in complete medium (RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, antibiotics, nonessential amino acids, pyruvate and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol) on 0.5 μg/ml immobilized anti-CD3 (2C11) with 1 μg/ml anti-CD28 (37.51; eBioscience) for various time points. T cells cultured under TH2 skewing conditions were incubated with 50 ng/ml IL-4 as well as neutralizing antibodies to IL-12 and IFN-γ (10 μg/ml from BD). Cells were also treated with antioxidants (10 mM N-acetylcysteine (NAC) or 100 μM apopcynin) or 1 μM 2,3-Dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (DMNQ) as a pro-oxidant during primary activation. After 48 hours stimulation of CD4+ T cells, or 72 hours stimulation of total splenocytes, the supernatants from each culture were collected for ELISA (R&D Systems), and the cells were harvested and extracted for mRNA isolation or analyzed by flow cytometry.

T cell blasts were generated and expanded in IL-2 as previously described [17]. T blasts were washed and restimulated 1 × 106 cells/ml for 8 hours with 0.5 μg/ml immobilized anti-CD3 and the supernatants from each culture were collected for analysis by ELISA. T cell blasts cultured in the presence of antioxidants were exposed to them throughout activation and subsequent expansion in IL-2.

Flow Cytometry

Following harvest and washing, cells were incubated for 15 minutes at 4°C with 5 μg/ml Fc Block (2.4G2; BD Pharmingen) and with a live/dead fixable marker (LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit; Invitrogen) and in some samples, surface stained for CD25 (PC61.5, eBioscience) or IL-4Rα (mIL4R-M1; BD Pharmingen). After incubation, the cells were washed twice and were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at 4°C. Following fixation, the cells were washed and then permeabilized in 80% methanol for 30 minutes at 4°C. Transcription factor expression was determined by intracellular staining with monoclonal antibodies specific for GATA-3 (TWAJ), and T-bet (4-B10) (all eBioscience). Phosphorylated STAT levels were determined by intracellular staining with antibodies specific for pY701-STAT1 (4a), pY705-STAT3 (4/P-STAT3), pY693-STAT4 (38/p-Stat4), pY694-STAT5 (47), and pY641-STAT6 (J71-773.58.11) (all BD Pharmingen). Total STAT5 levels were determined by staining with a purified pan-STAT5 antibody (89, BD Pharmingen) followed by a F(ab’)2 donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Positive staining and mean fluorescence intensity was determined by flow cytometry gating on viable T cells and analysis using FlowJo (Ashland, OR). Mean fluorescence intensity was calculated as the difference in stimulated samples from unstimulated controls.

Western Blotting for pSTAT5

Western blot analysis was performed essentially as previously described [47], using antibodies specific for pY694-STAT5 (D47E7, Cell Signaling Technology) and total STAT5 (3H7, Cell Signaling Technology).

Quantitative PCR

For analysis of NOX2 expression, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were purified by positive selection from spleen or lymph node by magnetic bead isolation (BioMag) using antibodies against CD4 and CD8 at 5 μg/ml (53-6.7 and GK1.5; eBioscience), while for thymus, double negative thymocytes were isolated by negative selection using antibodies against CD4 and CD8 at 5 μg/ml to remove mature thymocytes. Total RNA was isolated from cells or whole tissue using the NucleoSpin RNA II Total RNA Isolation kit (Macherey-Nagel).

Reverse transcription was carried out using the AffinityScript RT-PCR kit (Agilent). mRNA levels in cultured cells were quantified by qRT-PCR (Agilent Brilliant SYBR Green-based qPCR) on a 7900HT real-time thermal cycler (ABI) using primers previously described.[48-50] Aorta, a source of primary tissue known to express multiple isoforms [51] was used as a positive control. The following primer sets were used in these studies: GATA-3, forward (5′-GAGGTGGTGTCTGCATTCCAA-3′) and reverse (5′-TTTCACAGCACTAGAGACCCTGTTA-3′); IL-2, forward (5′-CCTGAGCAGGATGGAGAATTACA-3′) and reverse (5′-TCCAGAACATGCCGCAGAG-3′); IL-4, forward (5′-GCATTTTGAACGAGGTCACAGG-3′) and reverse (5′-TATGCGAAGCACCTTGGAAGC-3′); IL-4Rα, forward (5′-ATGTTCTTCGAGTTCTCTGAAAACC-3′) and reverse (5′-TCTGATTGGACCGGCCTATT-3′); NOX2, forward (5′-ACCTTACTGGCTGGGATGAA-3′) and reverse (5′-TGCAATGGTCTTGAACTCGT-3′); T-bet, forward (5′-GTTCCCATTCCTGTCCTTC-3′) and reverse (5′-CCTTGTTGTTGGTGAGCTT-3′). Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated based on the delta CT method.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance was analyzed using student’s T-test and the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Conditions were deemed significantly different if p< 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of Dr. Jonathan Bromberg’s lab for their generous sharing of resources. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-AI070823 (to M.S.W.) and National Institutes of Health Grant T32-HL007698 (to K.E.S.). K.E.S. is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Maryland School of Medicine Graduate Program in Life Sciences (GPILS) and this work is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for her Ph.D.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen presenting cell

- CGD

chronic granulomatous disease

- DMNQ

2,3-Dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- NOX2

NADPH Oxidase 2

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

Footnotes

Author Contributions

K.E.S., H.C. and J.K. performed experiments

K.E.S., H.C., J.K. and M.S.W. analyzed results and made the figures

K.E.S. and M.S.W. designed the research and wrote the article

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lambeth JD. NOX Enzymes and the Biology of Reactive Oxygen. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2004;4:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nri1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stasia MJ, Li XJ. Genetics and immunopathology of chronic granulomatous disease. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2008;30:209–235. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song E, Jaishankar GB, Saleh H, Jithpratuck W, Sahni R, Krishnaswamy G. Chronic granulomatous disease: a review of the infectious and inflammatory complications. Clinical and Molecular Allergy. 2011;9:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenzweig SD. Inflammatory Manifestations in Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD) Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2009;28:S67–S72. doi: 10.1007/s10875-007-9160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang A, Abbasakoor F, Vaizey CJ. Gastrointestinal manifestations of chronic granulomatous disease. Colorectal Disease. 2006;8:637–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manzi S, Urbac AH, McCune AB, Altman HA, Kaplan SS, T AM, Ramsey-Goldman R. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a Boy with Chronic Granulomatous Disease: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1991;34:101–105. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.vandeLoo FAJ, Bennink MB, Arntz OJ, Smeets RL, Lubberts E, Joosten LAB, Lent P. L. E. M. v., Roo C. J. J. C.-d., Cuzzocrea S, Segal BH, Holland SM, Berg W. B. v. d. Deficiency of NADPH Oxidase Components p47phox and gp91phox Caused Granulomatous Synovitis and Increased Connective Tissue Destruction in Experimental Arthritis Models. American Journal of Pathology. 2003;163:1525–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63509-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hultqvist M, Olofsson P, Holmberg J, Backstrom BT, Tordsson J, Holmdahl R. Enhanced autoimmunity, arthritis, and encephalomyelitis in mice with a reduced oxidative burst due to a mutation in the Ncf1 gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:12646–12651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403831101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snelgrove RJ, Edwards L, Rae AJ, Hussell T. An absence of reactive oxygen species improves the resolution of lung influenza infection. European Journal of Immunology. 2006;36:1364–1373. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snelgrove RJ, Edwards L, Williams AE, Rae AJ, Hussell T. In the Absence of Reactive Oxygen Species, T Cells Default to a TH1 Phenotype and Mediate Protection against Pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans Infection. Journal of Immunology. 2006;177:5509–5516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard TG, Yu F, Hsieh C-L, Redline RW. Severe Inflammation and Reduced Bacteria Load in Murine Helicobacter Infection Caused by Lack of Phagocyte Oxidase Activity. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2003;187:1609–1615. doi: 10.1086/374780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romani L, Fallarino F, Luca AD, Montagnoli C, D’Angelo C, Zelante T, Vacca C, Bistoni F, Fioretti MC, Grohmann U, Segal BH, Puccetti P. Defective tryptophan catabolism underlies inflammation in mouse chronic granulomatous disease. Nature. 2008;451:211–216. doi: 10.1038/nature06471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George-Chandy A, Nordstrom I, Erik Nygren, Jonsson I-M, Postigo J, Collins LV, Eriksson K. TH17 development and autoimmune arthritis in the absence of reactive oxygen species. European Journal of Immunology. 2008;36:1118–1126. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tse HM, Thayer TC, Steele C, Cuda CM, Morel L, Piganelli JD, Mathews CE. NADPH Oxidase Deficiency Regulates TH Lineage Commitment and Modulates Autoimmunity. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185:5247–5258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelderman KA, Hultqvist M, Pizzolla A, Zhao M, Nandakumar KS, Mattsson R, Holmdahl R. Macrophages suppress T cell responses and arthritis development in mice by producing reactive oxygen species. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:3020–3028. doi: 10.1172/JCI31935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelderman KA, Hultqvist M, Holmberg J, Olofsson P, Holmdahl R. T cell surface redox levels determine T cell reactivity and arthritis susceptibility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:12831–12836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604571103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson SH, Devadas S, Kwon J, Pinto LA, Williams MS. T cells express a phagocyte-type NADPH oxidase that is activated after T cell receptor stimulation. Nature Immunology. 2004;5:818–827. doi: 10.1038/ni1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thayer TC, Delano M, Liu C, Chen J, Padgett LE, Tse HM, Annamali M, Piganelli JD, Moldawer LL, Mathews CE. Superoxide Production by Macrophages and T Cells Is Critical for the Induction of Autoreactivity and Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:2144–2151. doi: 10.2337/db10-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Purushothaman D, Sarin A. Cytokine-dependent regulation of NADPH oxidase activity and the consequences for activated T cell homeostasis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2009;206:1515–1523. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li-Weber M, Giaisi M, Treiber MK, Krammer PH. Vitamin E inhibits IL-4 gene expression in peripheral blood T cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2002;32:2401–2408. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200209)32:9<2401::AID-IMMU2401>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann FW, Hashimoto AC, Shafer LA, Dow S, Berry MJ, Hoffmann PR. Dietary Selenium Modulates Activation and Differentiation of CD4+ T Cells in Mice through a Mechanism Involving Cellular Free Thiols. Journal of Nutrition. 2010;140:1155–1161. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.120725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King MR, Ismail AS, Davis LS, Karp DR. Oxidative Stress Promotes Polarization of Human T Cell Differentiation toward a T Helper 2 Phenotype. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:2765–2772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Shea JJ, Paul WE. Mechanisms Underlying Lineage Commitment and Plasticity of Helper CD4+ T Cells. Science. 2010;327:1098–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1178334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson CB, Rowell E, Sekimata M. Epigenetic control of T-helper-cell differentiation. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2009;9:91–105. doi: 10.1038/nri2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cote-Sierra J, Foucras G, Guo L, Chiodetti L, Young HA, Hu-Li J, Zhu J, Paul WE. Interleukin 2 plays a central role in TH2 differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:3880–3885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400339101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu J, Cote-Sierra J, Guo L, Paul WE. STAT5 Activation Plays a Critical Role in TH2 Differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:739–748. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamane H, Zhu J, Paul WE. Independent roles for IL-2 and GATA-3 in stimulating naive CD4+ T cells to generate a TH2-inducing cytokine environment. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;202:793–804. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao W, Schones DE, Oh J, Cui Y, Cui K, Roh T-Y, Zhao K, Leonard WJ. Priming for T helper type 2 differentiation by interleukin 2-mediated induction of interleukin 4 receptor a-chain expression. Nature Immunology. 2008;9:1288–1296. doi: 10.1038/ni.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakir H, Wanga H, Lefebvrea DE, Webbb J, Scott FW. T-bet/GATA-3 ratio as a measure of the TH1/TH2 cytokine profile in mixed cell populations: predominant role of GATA-3. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2003;278:157–169. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong L, Chen M, Zhang Q, Li L.-z., Xu X.-q., Xiao W. T-bet/GATA-3 ratio is a surrogate measure of TH1/TH2 cytokine profiles and may be novel targets for CpG ODN treatment in asthma patients. Chinese Medical Journal. 2006;119:1396–1399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stritesky GL, Muthukrishnan R, Sehra S, Goswami R, Pham D, Travers J, Nguyen ET, Levy DE, Kaplan MH. The Transcription Factor STAT3 Is Required for T Helper 2 Cell Development. Immunity. 2011;34:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Devadas S, Zaritskaya L, Rhee SG, Larry Oberley, Williams MS. Discrete Generation of Superoxide and Hydrogen Peroxide by T Cell Receptor Stimulation: Selective Regulation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation and Fas Ligand Expression. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2002;195:59–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II - induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoch NE, Guzik TJ, Chen W, Deans T, Maalouf SA, Gratze P, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Regulation of T-cell function by endogenously produced angiotensin II. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2009;296:R208–216. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90521.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Donaldson M, Antignani A, Milner J, Zhu N, Wood A, Cardwell-Miller L, Changpriroa C, Jackson S. p47phox-deficient immune microenvironment signals dysregulate naive T-cell apoptosis. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2009;16:125–138. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tao X, Constant S, Jorritsma P, Bottomly K. Strength of TCR signal determines the costimulatory requirements for TH1 and TH2 CD4+ T cell differentiation. Journal of Immunology. 1997;159:5956–5963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yagi R, Zhu J, Paul WE. An updated view on transcription factor GATA3-mediated regulation of TH1 and TH2 cell differentiation. International Immunology. 2011;23:415–420. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welte T, Leitenberg D, Dittel BN, al-Ramadi BK, Bing Xie, Y EC, Jr., C AJ, Bothwell ALM, Bottomly K, Fu X-Y. STAT5 Interaction with the T Cell Receptor Complex and Stimulation of T Cell Proliferation. Science. 1999;283:222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwon J, Qu C-K, Maeng J-S, Falahati R, Lee C, Williams MS. Receptor-stimulated oxidation of SHP-2 promotes T-cell adhesion through SLP-76-ADAP. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24:2331–2341. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu C-L, Jin Y-J, Burakoff SJ. Cytosolic tyrosine dephosphorylation of STAT5. Potential role of SHP-2 in STAT5. 2000;275:599–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y, Wen R, Yang S, Schuman J, Zhang EE, Yi T, Feng G-S, Wang D. Identification of SHP-2 as a STAT5a Phosphatase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:16520–16527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jenner RG, Townsend MJ, Jackson I, Sun K, Bouwman RD, Young RA, Glimcher LH, Lord GM. The transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3 control alternative pathways of T-cell differentiation through a shared set of target genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:17876–17881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909357106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X-P, Ghoreschi K, Steward-Tharp SM, Rodriguez-Canales J, Zhu J, Grainger JR, Hirahara K, Sun H-W, Wei L, Vahedi G, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ, Laurence A. Opposing regulation of the locus encoding IL-17 through direct, reciprocal actions of STAT3 and STAT5. Nature Immunology. 2011;12:247–255. doi: 10.1038/ni.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Efimova O, Szankasi P, Kelley TW. Ncf1 (p47phox) Is Essential for Direct Regulatory T Cell Mediated Suppression of CD4+ Effector T Cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasui M, Hattori K, Taniuchi S, Kohdera U, AtushiNishikawa, Kinoshita Y, Kobayashi Y. Decreased CD4+CD29+ (Memory T) Cells in Patients with Chronic Granulomatous Disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1993;167:983–985. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bleesing JJ, Souto-Carneiro MM, Savage WJ, Brown MR, Martinez C, Yavuz S, Brenner S, Siegel RM, Horwitz ME, Lipsky PE, Malech HL, Fleisher TA. Patients with Chronic Granulomatous Disease Have a Reduced Peripheral Blood Memory B Cell Compartment. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:7096–70103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.7096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwon J, Shatynski KE, Chen H, Morand S, Deken X. d., Miot F, Leto TL, Williams MS. The Nonphagocytic NADPH Oxidase Duox1 Mediates a Positive Feedback Loop During T Cell Receptor Signaling. Science Signaling. 2010;3:ra59. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ertesvag A, Austenaa LMI, Carlsen H, Blomhoff R, Blomhoff HK. Retinoic acid inhibits in vivo interleukin-2 gene expression and T-cell activation in mice. Immunology. 2009;126:514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas RM, Chen C, Chunder N, Ma L, Taylor J, Pearce EJ, Wells AD. Ikaros Silences T-bet Expression and Interferon-g Production during T Helper 2 Differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:2545–2553. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buggisch M, Ateghang B, Ruhe C, Strobel C, Lange S, Wartenberg M, Sauer H. Stimulation of ES-cell-derived cardiomyogenesis and neonatal cardiac cell proliferation by reactive oxygen species and NADPH oxidase. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120:885–894. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El-Awady MS, Ansari HR, Fil D, Tilley SL, Mustafa SJ. NADPH oxidase pathway is involved in aortic contraction induced by A3 adenosine receptor in mice. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2011;338:711–717. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.180828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.