Abstract

A prognostic model that predicts overall survival (OS) for metastatic urothelial cancer (MetUC) patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy was developed, validated, and compared with a commonly used Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) risk-score model. Data from 7 protocols that enrolled 308 patients with MetUC were pooled. An external multi-institutional dataset was used to validate the model. The primary measurement of predictive discrimination was Harrell’s c-index, computed with 95% confidence interval (CI). The final model included four pretreatment variables to predict OS: visceral metastases, albumin, performance status, and hemoglobin. The Harrell’s c-index was 0.67 for the four-variable model and 0.64 for the MSKCC risk-score model, with a prediction improvement for OS (the U statistic and its standard deviation were used to calculate the two-sided P = .002). In the validation cohort, the c-indices for the four-variable and the MSKCC risk-score models were 0.63 (95% CI = 0.56 to 0.69) and 0.58 (95% CI = 0.52 to 0.65), respectively, with superiority of the four-variable model compared with the MSKCC risk-score model for OS (the U statistic and its standard deviation were used to calculate the two-sided P = .02).

A widely used model predicting overall survival (OS) for metastatic urothelial cancer (MetUC) patients treated with cisplatin chemotherapy is based on two prognostic factors—visceral (lung, liver, or bone) metastases and Karnofsky performance status less than 80%—was developed at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) (1). In this analysis of 203 patients with MetUC, median OS for patients with zero, one, or two risk factors were 33, 13.4, and 9.3 months, respectively (P < .001). This model has been validated in two randomized phase III trials of MetUC patients receiving platinum-based therapy (2,3).

The objective of this study was to develop a pretreatment prognostic model that could be used to predict 1-, 2-, and 5-year survival probability and median OS in MetUC patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy and to improve prognostic accuracy over the MSKCC model.

The development dataset for this study included 308 MetUC patients who received cisplatin-based chemotherapy on seven prospective phase II trials with similar inclusion criteria at MSKCC from 1983 to 2003 (Table 1) (1, 4–12). All study participants gave written informed consent for participation in the corresponding clinical trial, and the study protocols were approved by the respective institutional review boards.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics*

| Characteristic | Nomogram development cohort | Validation cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSKCC MVAC (n = 203) | MSKCC ITP (n = 45) | MSKCC AG-ITP (n = 60) | CALGB 90102 GC-gefitinib (n = 74) | |

| Male:female | 163:40 | 33:12 | 46:14 | 58:16 |

| Median age | 63 | 63 | 62 | 64 |

| Median KPS, % | 80 | 80 | 90 | 90 |

| Visceral disease, % | 49 | 40 | 33 | 69 |

| Bone | 26 | 11 | 10 | 18 |

| Liver | 13 | 13 | 10 | 31 |

| Lung | 26 | 22 | 18 | 43 |

| Risk factors, % | ||||

| 0 | 33 | 55 | 62 | 30 |

| 1 | 45 | 41 | 35 | 65 |

| 2 | 22 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Median survival, months (95% CI) | 14.8 (12.1 to 16.7) | 18 (12.0 to 29.7) | 16.4 (14.6 to 22.9) | 12.7 |

| Failed/censored, No. | 184/19 | 37/8 | 53/7 | 68/6 |

*AG-ITP = doxorubicin plus gemcitabine followed by ifosfamide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin; CI = confidence interval; GC = gemcitabine and cisplatin; ITP = ifosfamide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin; KPS = Karnofsky performance status; MSKCC = Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center; MVAC = methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin.

The primary endpoint was OS, defined as the time from initiation of chemotherapy until death or date of last follow-up. Predictors of OS were considered based on the literature (13–20). Univariate and multivariable analyses used the proportional hazards model for predicting OS; proportional hazards assumption was verified using test for weighted residuals (21). The final model was chosen based on univariate and multivariable P values (statistically significant if ≤.05). All statistical tests were two-sided. The model was internally validated, and its accuracy was assessed using Harrell’s concordance probability, c-index (22). Bootstrap samples (N = 1000) were used to estimate overfitting. The U statistic was used to test whether the predictions of the four-variable model in all possible pairs were more concordant with actual observations than the MSKCC risk-score model in the same pairs. Statistical analyses were performed using R (23) and its Design and Hmisc libraries (24).

The MSKCC risk-score and four- variable models were externally validated by an author (S. Halabi) who was not involved in the development of the prognostic model. The validation cohort, CALGB 90102, included 74 MetUC patients treated with cisplatin, gemcitabine, and gefitinib and enrolled from July 2002 to April 2005 with a median follow-up of 72.5 months (Table 1; Supplementary Figure 1B, available online).

In the nomogram development cohort there was no statistically significant difference in OS among the chemotherapy regimens (doxorubicin, gemcitabine, ifosfamide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin (AGITP) median OS = 16.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 14.6 to 22.9; ifosfamide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin (ITP) median OS = 18.0, 95% CI = 12.0 to 29.7; methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (M-VAC) median OS = 14.8, 95% CI = 12.1 to 16.7; P = .62) (Supplementary Figure 1A, available online). Median survivals by regimen are shown in Table 1. Univariate analyses for predictors of OS included lactate dehydrogenase; albumin, cubic splines using actual values (4 = no additional risk, whereas <4 or >4 = additional risk); hemoglobin, normal vs below normal (below normal for females was <11.5g/dL and for males was <13g/dL); Karnofsky performance status, good (≥80) vs poor (<80); body surface area; alkaline phosphatase; sex; body mass index; and visceral metastases (ie, lung, liver, bone, or other non–lymph node metastasis) present vs absent on standard imaging. All variables except body surface area, sex, and body mass index were statistically significantly associated with OS. Alkaline phosphatase and lactate dehydrogenase were no longer statistically significant after all other predictors were added and were not included in the multivariable model (Supplementary Table 1, available online).

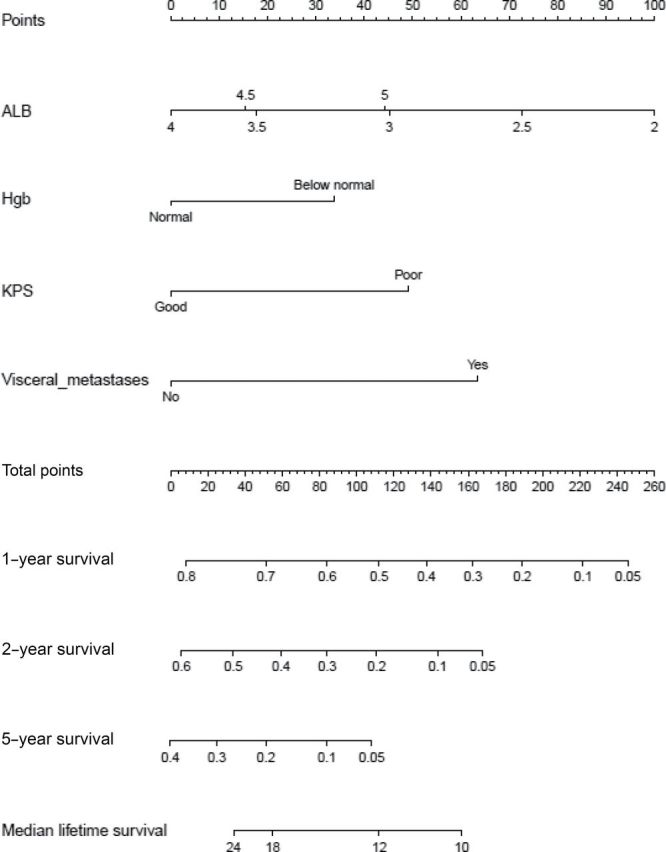

The final multivariable model included visceral metastases (P < .001), albumin (P < .001), Karnofsky performance status (P < .001), and hemoglobin (P = .005). The nomogram based on the corresponding proportional hazards model may be used to predict 1-, 2-, and 5-year survival probabilities and median OS (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Nomogram for predicting survival of patients with metastatic or unresectable urothelial cancer treated with cisplatin chemotherapy. To estimate survival, calculate points for each predictor by drawing a straight line from patient’s value to the axis labeled “Points.” Add all points, and draw a straight line from the total point axis to the 1-year, 2-year, 5-year, or median survival (months) axis. ALB = albumin; Hgb = hemoglobin; KPS = Karnofsky performance status.

The model was internally validated with c-index equal to 0.67 (bootstrap corrected c-index = 0.67). Calibration curves for 1-, 2-, and 5-year probability of survival are shown in Supplementary Figure 2 (available online). The differences between predicted and observed median survival in quartiles of patients defined by predicted median OS are 1.5, 0.5, –9.3, and 5.7 months, respectively. To compare the model with the previously developed MSKCC risk-score model (1), another Cox regression model was fitted using only the risk variable that takes values 0, 1, and 2 based on Karnofsky performance status (>80) and presence of visceral metastasis. This reduced model had a c-index equal to 0.64 (bootstrap corrected = 0.64), which was inferior to the proposed four-variable model (P = .002).

When the nomogram was applied to the validation cohort, the c-indices for the four-variable and MSKCC risk-score models were 0.63 (95% CI = 0.56 to 0.69) and 0.58 (95% CI = 0.52 to 0.65), respectively. Superiority of the four-variable model compared with the MSKCC risk-score model remained (P = .02).

This study reports and validates a prognostic model for predicting survival probabilities at 1-, 2-, and 5-year survival and median OS in patients with MetUC patients treated with first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy. This four-variable prognostic nomogram was superior to the MSKCC risk-score model.

The prognosis is quite variable for MetUC patients treated with first-line chemotherapy (2,4–10, 25–28), and both patients and clinicians would benefit from knowing the probability of survival.

Prognostic factors and risk-groups are often used in the design, conduction, and analysis of trials in genitourinary malignancies (29). The distribution of prognostic factors within a trial may influence response and survival and bias the estimated treatment benefit. Pretreatment stratification with this four-variable prognostic model in prospective phase II or III trials in MetUC patients could ensure similarity of cohorts for comparison and reduce the likelihood that survival differences are a function of patient characteristics. The prognostic model may also be used for comparing OS results across phase II trials.

There are multiple strengths of the four-variable model compared with the MSKCC risk-score model beyond statistical superiority. This model incorporates a larger number of MetUC patients from seven protocols. The model was also validated externally using a cooperative group trial.

There are limitations to the four- variable model. First, the patients participated in clinical trials, and there is the potential that the model may not be predictive for patients ineligible for protocol therapy. Moreover, it has yet to be validated in non–cisplatin-treated patients. Second, the model did not include factors such as histology or molecular markers that may influence survival (30–37). Lastly, the 5-year survival in patients with MetUC is less than 10%; therefore, the robustness of the model’s 5-year survival prediction is low. Despite these limitations, the model can be used clinically, and this methodology lends itself well for refinement as other prognostic factors are identified in the future.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Training Grant (T-32CA09207) and the Zena and Michael A. Wiener Research and Therapeutic Program in Bladder Cancer.

The study sponsors did not have a role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

The developed nomogram was initially presented at the 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting poster discussion session in Genitourinary Cancer (J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18S):5055). The validation of the nomogram was presented at the 2012 ASCO Annual Meeting general poster session in genitourinary cancer (J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl):abstract 4592).

References

- 1. Bajorin DF, Dodd PM, Mazumdar M, et al. Long-term survival in metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma and prognostic factors predicting outcome of therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17(10):3173–3181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bellmunt J, von der Maase H, Mead GM, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing paclitaxel/cisplatin/gemcitabine (PCG) and gemcitabine/cisplatin (GC) in patients with locally advanced (LA) or metastatic (M) urothelial cancer without prior systemic therapy; EORTC30987/Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007; 25(suppl):abstract LBA5030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Santis M, Bellmunt J, Mead G, et al. Randomized phase II/III trial assessing gemcitabine/carboplatin and methotrexate/carboplatin/vinblastine in patients with advanced urothelial cancer who are unfit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy: EORTC study 30986. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30(2):191–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCaffrey JA, Hilton S, Mazumdar M, et al. Phase II randomized trial of gallium nitrate plus fluorouracil versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in patients with advanced transitional-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1997; 15(6):2449–2455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gabrilove JL, Jakubowski A, Scher H, et al. Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on neutropenia and associated morbidity due to chemotherapy for transitional-cell carcinoma of the urothelium. N Engl J Med. 1988; 318(22) 1414–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dodd PM, McCaffrey JA, Mazumdar M, et al. Phase II trial of intermediate dose methotrexate in combination with vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in patients with unresectable or metastatic transitional cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1999; 85(5):1145–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seidman AD, Scher HI, Gabrilove JL, et al. Dose-intensification of MVAC with recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor as initial therapy in advanced urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993; 11(3) 408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sternberg CN, Yagoda A, Scher HI, et al. Methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin for advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium. Efficacy and patterns of response and relapse. Cancer. 1989; 64(12): 2448–2458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bajorin DF, McCaffrey JA, Hilton S, et al. Treatment of patients with transitional-cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract with ifosfamide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin: a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 1998; 16(8):2722–2727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Milowsky MI, Nanus DM, Maluf FC, et al. Final results of sequential doxorubicin plus gemcitabine and ifosfamide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with metastatic or locally advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27(25): 4062–4067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Philips GK, Halabi S, Sanford BL, Bajorin D, Small EJ. A phase II trial of cisplatin, fixed dose-rate gemcitabine and gefitinib for advanced urothelial tract carcinoma: results of the Cancer and Leukaemia Group B 90102. BJU Int. 2008; 101(1):20–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Philips GK, Halabi S, Sanford BL, Bajorin D, Small EJ. A phase II trial of cisplatin (C), gemcitabine (G) and gefitinib for advanced urothelial tract carcinoma: results of Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 90102. Ann Oncol. 2009; 20(6):1074–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bellmunt J, Albanell J, Paz-Ares L, et al. Pretreatment prognostic factors for survival in patients with advanced urothelial tumors treated in a phase I/II trial with paclitaxel, cisplatin, and gemcitabine. Cancer. 2002; 95(4) 751–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jessen C, Agerbaek M, Von Der Maase H. Predictive factors for response and prognostic factors for long-term survival in consecutive, single institution patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic transitional cell carcinoma following cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2009; 48(3): 411–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23(21):4602–4608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lin C-C, Hsu C-H, Huang C-Y, et al. Prognostic factors for metastatic urothelial carcinoma treated with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil-based regimens. Urology. 2007; 69(3): 479–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stadler WM, Hayden A, von der Maase H, et al. Long-term survival in phase II trials of gemcitabine plus cisplatin for advanced transitional cell cancer. Urologic Oncol. 2002; 7(4): 153–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sengelov L, Nielsen OS, Kamby C, von der Maase H. Platinum analogue combination chemotherapy: cisplatin, carboplatin, and methotrexate in patients with metastatic urothelial tract tumors. A phase II trial with evaluation of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1995; 76(10): 1797–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Geller NL, Sternberg CN, Penenberg D, Scher H, Yagoda A. Prognostic factors for survival of patients with advanced urothelial tumors treated with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin chemotherapy. Cancer. 1991; 67(6):1525–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28(11):1850–1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grambsch P, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994; 81(3):515–526 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harrell FE Jr Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gentleman R, Ihaka R. The R Project for Statistical Computing. http://www.r-project.org; 2012. Accessed January 17, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harrell F. Design: S-Plus Function for Biostatistical/Epidemiological Modeling, Testing, Estimation, Validation, Graphics, Prediction, and Typesetting by Storing Enhanced Model Design Attributes in the Fit. http://wwwstatlib@libstatcmuedu Accessed January 17, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Logothetis CJ, Dexeus FH, Finn L, Sella A, Amato RJ, Ayala AG, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing MVAC and CISCA chemotherapy for patients with metastatic urothelial tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1990; 8(6):1050–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loehrer PJ, Sr, Einhorn LH, Elson PJ, et al. A randomized comparison of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992; 10(7):1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dreicer R, Manola J, Roth BJ, et al. Phase III trial of methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin versus carboplatin and paclitaxel in patients with advanced carcinoma of the urothelium. Cancer. 2004; 100(8):1639–1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 18(17):3068–3077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Halabi S, Owzar K. The importance of identifying and validating prognostic factors in oncology. Semin Oncol. 2010; 37(2):e9–e18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scosyrev E, Ely BW, Messing EM, et al. Do mixed histological features affect survival benefit from neoadjuvant platinum-based combination chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced bladder cancer? A secondary analysis of Southwest Oncology Group-Directed Intergroup Study (S8710). BJU Int. 2011; 108(5):693–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Al-Ahmadie HA, Iyer G, Janakiraman M, et al. Somatic mutation of fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 (FGFR3) defines a distinct morphological subtype of high-grade urothelial carcinoma. J Pathol. 2011; 224(2):270–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bellmunt J, Paz-Ares L, Cuello M, et al. Gene expression of ERCC1 as a novel prognostic marker in advanced bladder cancer patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2007; 18(3):522–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fauconnet S, Bernardini S, Lascombe I, et al. Expression analysis of VEGF-A and VEGF-B: relationship with clinicopathological parameters in bladder cancer. Oncol Rep. 2009; 21(6):1495–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang C-C, Chu K-C, Yeh W-M. The expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder is correlated with cancer progression. Urologic Oncol. 2004; 22(1):1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bernardini S, Fauconnet S, Chabannes E, Henry PC, Adessi G, Bittard H. Serum levels of vascular endothelial growth factor as a prognostic factor in bladder cancer. J Urol. 2001; 166(4):1275–1279 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crew JP, O’Brien TIM, Bicknell ROY, Fuggle SUE, Cranston D, Harris AL. Urinary vascular endothelial growth factor and its correlation with bladder cancer recurrence rates. J Urol. 1999; 161(3):799–804 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gallagher D, Joseph V, Garcia-Grossman IR, et al. Germline single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with response of urothelial carcinoma (UC) to platinum-based therapy: the role of the host. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29(suppl 7):abstract 236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]