Abstract

Objective

To investigate the differential effects of fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs(AEDs) on cognitive fluency and flexibility in a prospective sample of children.

Methods

This substudy of the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs investigation enrolled pregnant women with epilepsy on AED monotherapy (carbamazepine, lamotrigine and valproate). Blinded to drug exposure, 54 children were tested for ability to generate ideas in terms of quantity (fluency/flexibility) and quality (originality). 42 children met inclusion criteria (mean age=4.2 years; SD=0.5) for statistical analyses of group differences.

Results

Fluency was lower in the valproate group (mean=76.3; SD=7.53) vs.lamotrigine (mean=93.76; SD=13.5; ANOVA p<0.0015) and carbamazepine (mean=95.5; SD=18.1; ANOVA p<0.003). Originality was lower in the valproate group (mean=84.2; SD=3.23) vs. lamotrigine (mean=103.1; SD=14.8; ANOVA p<0.002) and carbamazepine (mean=99.4; SD=17.1; ANOVA p<0.01). These results were not explained by factors other than AED exposure.

Conclusion

Children prenatally-exposed to valproate demonstrate impaired fluency and originality compared to two other AEDs.

Introduction

Human studies of neurodevelopment suggest that children exposed in utero to certain antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) suffer a variety of brain-behavior sequelae compared to the developmental milestones of non-exposed children. These differences in neurodevelopment have been reported as developmental delays [1-5], deficits in general intelligence [6-7, 55], deficits in verbal intelligence [8-10], additional educational needs [9], and pervasive developmental disorders including autism [2, 3, 11-14]. Only several of over twenty AEDs currently in clinical use, however, have been examined in studies that measure cognitive outcomes in children prenatally-exposed to AED monotherapy as an assessment of neurobehavioral teratogenesis.

Although there are limitations to many prior studies, the present literature suggests that fetal exposure to valproate and, to a lesser extent, phenobarbitol increases the risk for cognitive deficits [7, 15-16]. One limitation of some prior human studies is the lack of a prospective design beginning early during pregnancy (Table 1). Without this design, the effects of factors such as maternal seizure frequency/severity, AED blood absorption levels, pregnancy risk factors, and early home environment cannot be reliably evaluated. Second, although valproate appears to be the AED associated with greatest risk for cognitive deficits and special education needs [7-10, 16], the effects of some commonly used AEDs have not been adequately addressed, such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbazepine, phenytoin, and topiramate. Third, most studies do not address differential AED effects across development, following subjects through early childhood with a longitudinal clinical and neuropsychological data collection protocol. Finally, behavioral outcome criteria in most neurobehavioral teratology studies are insufficient to determine functional deficits across a variety of human cognitive domains.

Table 1. Cognitive Outcomes for Valproate Subjects Across Human Studies.

| Study | Enrollment Design |

Blinded to AED |

Valproate MonoTx |

Other AED MonoTx |

Significant Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adab 2004[10] |

Retrospective | No | N=41 | Carbamazepine Phenytion | WISC-III[17] Verbal IQ |

| Gaily 2004[8] |

Prospective | Yes | N=13 | Carbamazepine | WPPSI-R[18] or WISC- R[19] Verbal IQ |

| Eriksson 2005[6] |

Prospective | Yes | N=21 | Carbamazepine | WISC-III IQ [17] |

| Meador 2009[7] |

Prospective | Yes | N=53 | Carbamazepine Lamotrigine Phenytoin |

DAS IQ [20] and BMDI [21] |

AED = Antiepileptic drug; MonoTx = Prenatal exposure to AED monotherapy; DAS = Differential Abilities Scales [20], a standardized intelligence quotient that measures generalized cognitive ability (GCA), administered to this cohort at 36–45 months; BMDI = Bayley Mental Development Index[21], a standardized behavioral measure of cognitive development, administered to this cohort at 21–34 months; WISC = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Childen [17, 19]; WPPSI = Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence [18].

In human behavioral teratology studies, cognitive function is predominately assessed by intelligence tests. Psychometric intelligence outcomes (‘IQ tests’) confer attractive experimental design advantages: IQ measures are well-standardized, sensitive to a variety of teratogens, predictive of conventional school performance, non-invasive, and facilitate comparing outcomes among studies. Despite these advantages, this strategy limits measurement of higher order cognition to convergent thinking (i.e. for a given stimulus, there is one correct response) and does not address a variety of cognitive domains.

Our ongoing prospective observational investigation entitled Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study has addressed many of the limitations in prior studies and demonstrated differential effects of AEDs on IQ [55]. However, no prior study has addressed the effects of fetal AED exposure on an essential component of higher order cognition: the ability to generate novel ideas with fluency and flexibility. The purpose of this substudy to the NEAD investigation was to examine the differential effects of fetal exposure to AEDs on divergent thinking (i.e. for a given stimulus, there are infinite correct responses), operationalized as fluency (quantity of ideas) and originality (quality of ideas). We hypothesized widespread teratogenesis across cognitive domains and predicted that the greatest effect would be seen in the valproate exposure group, manifest as a decreased ability to generate quantity of ideas (cognitive fluency) and quality of ideas (cognitive originality).

Methods

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards from each of the 13 participating NEAD Study clinical centers: The Medical College of Georgia, Emory University, The Minnesota Epilepsy Group, Georgetown University Medical Center, Baylor Medical Center, Harvard University Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Ohio State University, Riddle Memorial Hospital/Thomas Jefferson Hospital, Via Christi Medical Center, Wake Forest University, University of Cincinnati, and Columbia University. Informed consent was obtained from each child’s mother. Written assent from participating children was not obtained due to age.

Subjects

Women with epilepsy on carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin or valproate monotherapy were prospectively enrolled in the NEAD study during the first trimester of pregnancy between 1999 and 2004. The present substudy of NEAD participants included 54 preschool children ages 3.5 – 5.5 years. In the design phase of this substudy, phenytoin-exposed subjects were excluded due to feasibility concerns that made it improbable to provide statistical power. Consequently, because our recruitment and data collection protocol for testing volunteer subjects from the NEAD Study was blinded to AED exposure type, we also assessed several children exposed in utero to phenytoin monotherapy.

Seven inclusion criteria for the study included (1) child is born to a woman with epilepsy age 18–35 at time of pregnancy; (2) enrollment during first trimester; (3) in utero exposure to AED monotherapy carbamazepine, lamotrigine, or valproate; (4) in utero exposure for a minimum period of six months; (5) mother’s primary language is English; (6) mother’s intelligence tests in normal range (pre-enrollment screen: Test of Non-Verbal Intelligence - Revised (TONI-R)[22]; post-enrollment screen: Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)[23], and (7) child’s age is between 3.5 and 5.5 at time of Torrance Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement (TCAM)[24] administration. Exclusion criteria included (1) in utero exposure to another AED or polytherapy including a target monotherapy; (2) child is on a centrally active medication; (3) child has had a serious brain injury (i.e. severe head trauma) or serious medical illness (i.e. cancer) unrelated to AED exposure which may affect child’s cognitive abilities; (4) mother has had a serious medical illness or complication during the child’s pregnancy which is unrelated to the AED or the epilepsy; (5) mother has a known history of drug or alcohol abuse within the previous 12 months or has a sequelae of drug abuse; or (6) there was a known history of child abuse.

We excluded 11 study participants from the sample for phenytoin monotherapy (n=8), maternal report of polytherapy (n=1), maternal self-report of physical abuse to child (n=1), and non-compliance with testing procedures (n=1). Children with congenital abnormalities (n=2) were provided testing accommodations, but were not excluded from the sample: (a) a non-ambulatory girl in the carbamazepine exposure group had fine motor delays/deficits, was physically supported by her parents, and was encouraged to use verbal responses for the motor tasks, as per the TCAM test administration guidelines, and (b) a boy in the valproate exposure group with surgically-corrected polydactyly of the right thumb was assisted by his mother for hand use, and was also encouraged to use verbal responses as per TCAM guidelines.

The final sample in the analysis consisted of 42 children and their mothers (carbamazepine=16; lamotrigine=17; valproate=9). Mean chronological age was 4.2 years (SD=0.5), with non-significant differences for AED groups (p=0.83). Gender difference in the cohort (n=23 males; n=19 females) was not significant (p=0.53). Children were assessed for somatic malformations at birth and screened with physical and neurological exams that include growth measurements, auditory assessment and visuomotor assessment at 2 years, 3 years, and at age 4.5 years.

Neurobehavioral assessment

Cognitive fluency and originality was assessed during a home visit with the Torrance Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement (TCAM)[24]. Psychometric intelligence was assessed at age three using the Differential Abilities Scale (DAS-II Preschool Version)[20]. A comprehensive battery of neuropsychological development (intellectual function, motor function, adaptive function, and social-emotional function) has been longitudinally administered to the study cohort (2 year, 3 year, and 4.5 year visits), but not used in the present analyses, except for IQ from the Developmental Abilities Scale-Second Edition (described below).

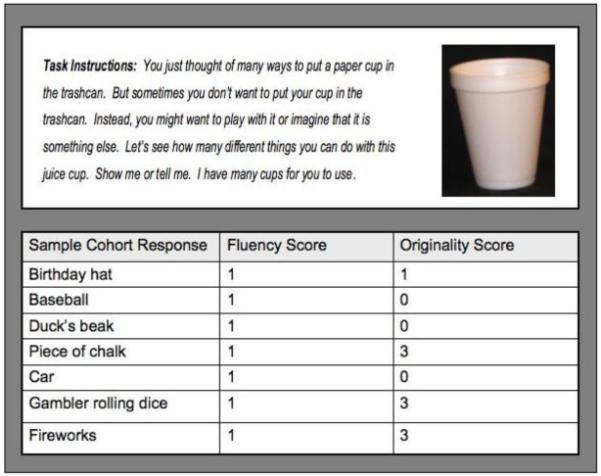

The Torrance Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement (TCAM) uses three experimental conditions to assess a substrate(s) of complex, higher-order cognition: the ability to generate ideas using divergent thinking processes. For each of three conditions, there are infinite correct responses, which are rated for quantity (“fluency”) and quality (“originality”). Data are collected by a trained examiner who observes and documents verbal and/or action responses in a response booklet. The response environment requires a defined floor area. Two conditions are paired with stimuli believed to be familiar to children and free of socioeconomic, racial and cultural bias (i.e. paper cups and a trashcan). Each condition uses an open-ended question, communicated verbally, to structure the activity (Figure 1): (1) How Many Ways?; (2) What Other Ways?; and (3) What Else Can It Be? Composite raw scores for each subtest are converted to standardized scores for fluency and originality.

Figure 1. Sample TCAM Experimental Condition and Cohort Responses.

The Torrance Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement (TCAM) is a standardized behavioral measure that uses familiar, simple stimuli to elicit a child’s ability to generate novel ideas, in terms of both quantity (cognitive fluency and flexibility) and quality (cognitive originality). In contrast to IQ tests, which are based on convergent thinking skills (i.e. for a given stimulus, there is one correct answer), the TCAM assays divergent thinking skills (i.e. for a given stimulus, there are infinite correct answers). The TCAM has three experimental conditions, or tasks, based on open-ended questions. In this figure, the instructions for one experimental condition (Task 3: “What else can it be?”) are paired with a paper cup. Actual responses from the study sample are presented here, with raw fluency scores and norm-referenced originality scores.

Construct validity studies for this psychometric instrument are favorable, including 52 studies in the 1992 Cumulative Bibliography of Thinking Creatively in Action Movement and a peer review in The Ninth Mental Measurements Yearbook[25]. Across sub-test conditions, the test-retest reliability coefficient is .84. Interrater reliability ranges from .96 to .99 for fluency scores and originality scores, with no significant differences reported for the means. Behavioral studies that quantify the generation of ideas within a developmental context report that preschool is an optimal time for assessing this cognitive domain based on evidence suggesting (1) that expressiveness peaks at age five, begins to decline in first grade, and re-emerges for some but not all in adolescence[26,27]; (2) that composite imagination scores across response modalities is highest between ages 4 years and 4 years six months; and (3) that “don’t know” responses decrease with chronological age up to five years and then increase[24,28].

The Differential Abilities Scale - Second Edition (DAS-II Preschool Version) is a standardized measure of convergent thinking: each stimulus has one and only one correct response [20]. The Lower Preschool Level of the DAS is comprised of 4 subtests: block building skills, nonverbal reasoning, verbal comprehension, and naming vocabulary. Together, these subtests yield a General Conceptual Ability score (GCA). The internal reliabilities for the subtests comprising the Lower Preschool Level range from .73 to .86 and the internal reliabilities for the GCA score range from .89 to .91. Test-retest reliabilities for the subtests range from .56 to .81, while the test-retest reliability for the GCA is .90. Concurrent validity studies show that the GCA for the DAS correlates .89 with the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised and .77 with the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, Fourth Edition.

Maternal Intelligence

The Test of Nonverbal Intelligence - Third Edition (TONI-3)[22] is used as a screening measure of general cognitive function in mothers. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale -Third Edition (WAIS-III)[23] is used to obtain psychometric intelligence of mother upon enrollment.

Prenatal and Perinatal Risk Factors

Prenatal and perinatal variables are recorded during pregnancy using seizure journals, serious adverse event reports, and clinical evaluations reported by the investigator-neurologist managing the epilepsy of enrolled mother. These risk factors include pregnancy vitamins with or without folate; lifestyle choices (defined as “ethanol consumption” or “nicotine use”); and obstetrical complications. All reports are audited by a central administrator to ensure accurate data collection, and all data are maintained in a centralized data management center at the EMMES Corporation: Rockville, MD.

Pregnancy complications included maternal thyroid disease (carbamazepine=1; valproate=1), urinary tract or vaginal infection (lamotrigine=2; carbamazepine=1), seizure occurrence (lamotrigine=1 generalized tonic-clonic seizure) gestational diabetes (valproate=1; lamotrigine=1; carbamazepine=1), fetal distress (carbamazepine=3; lamotrigine=4), premature birth (carbamazepine=2), and neonatal seizure activity (carbamazepine=1). Six subjects report more than one prenatal complication (carbamazepine=3; lamotrigine=3; valproate=0).

Maternal Total Daily Dose

Total daily dose exposure is known for each subject and is reported based on average daily dose across the entire pregnancy.

Daily dose range is from 200 to 1500 milligrams for carbamazepine (median=800); from 200 to 900 milligrams for lamotrigine (median=400); and from 750 to 2750 for valproate (median=1250). Given the differing dose ranges for each AED, coupled with small sample size per exposure group, it was not possible to directly test for dose-by-drug effects. Rather, a descriptive analysis was performed by comparing the effects of high and low doses of each drug with reference to the sample’s median dose.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses are conducted using SAS JMP IN Version 5.1.2 [29] and SAS Version 9 [30]. One-way ANOVA is calculated for TCAM outcomes fluency and originality to test for differential effects of drug exposure. Further analysis employed Student’s t-tests to examine differences in TCAM measures between drug exposure groups. Drug dosage was not included as a factor in these analyses. Bivariate regression models are used to test potential confounding factors for association with TCAM outcomes, including maternal seizure type, maternal IQ (WAIS), pregnancy risk factors (seizures, obstetrical complications, maternal illness, and recreational drugs), prenatal vitamins, breastfeeding, child gender, and child IQ at 3 years (DAS). For these analyses, the Bonferroni method is used to correct for multiple comparisons for each TCAM outcome.

Results

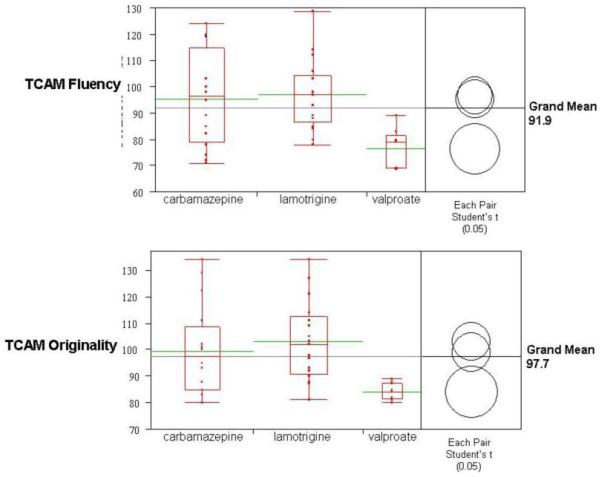

We treated each drug exposure group (carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproate) as an independent variable. Plots of the distribution of the TCAM measures for each drug exposure group are shown in Figure 2. Overall, there is a main effect of AED in utero exposure for both TCAM fluency and originality (Table 2). For TCAM fluency, group mean for valproate (76.3; SD=7.53) is significantly different than group means for lamotrigine (p<0.0015) and carbamazepine (p<0.003). Similarly, for TCAM originality, group mean for valproate (84.2; SD=3.23) is significantly different than for lamotrigine (p<0.002) and carbamazepine (p<0.01). No significant difference was found between lamotrigine and carbamazepine.

Figure 2. Fetal Exposure Group Differences for Fluency and Originality.

The horizontal grey lines indicates ANOVA grand means (fluency=91.9; originality=97.7). The boxplots for each AED exposure group show (a) individual performance (red data points arrayed vertically), (b) the interquartile range (top and bottom of the box), (c) group means (green horizontal bars), and (d) group distribution (spread of the “tails” or “whiskers”). The comparison circles compute individual pairwise comparisons using Student’s t-tests. Each circle corresponds to a drug exposure group: If the mean for one drug group is significantly different than the mean for another drug group, their circles do not intersect, or their circles intersect slightly, so that the outside angle of intersection is less than 90 degrees, as is the case with the valproate group versus the carbamazepine and lamotrigine groups (i.e. fluency mean = 76.3, with p-value = 0.003 for carbamazepine and p-value = 0.001 for lamotrigine). If the circles intersect by an angle of more than 90 degrees, or if the circles are nested, the means are not significantly different, as is the case with the carbamazepine and lamotrigine groups.

Table 2. Fetal Exposure Group Outcomes: One-way Analyses of Variance for Cognitive Fluency and Originality.

| TCAM Outcome |

ANOVA p-value |

All n=42 |

Carbamazepine n=16 |

Lamotrigine n=17 |

Valproate n=9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Fluency | 0.003 | 91.9 (16.4) | 95.5 (18.1) | 96.76 (13.5) | 76.3 (7.53)* |

| Originality | 0.004 | 97.7 (15.7) | 99.4 (17.1) | 103.1 (14.8) | 84.2 (3.23)* |

For both TCAM measures, a higher scores indicates a better outcome; a score of 100 represents the mean for the normative sample. “SD” refers to standard deviation.

An asterisk refers to significance at p < 0.05 level by one-way ANOVA.

Bivariate regression analyses are reported in Table 3. Continuous measures (i.e. maternal IQ and child IQ) are dichotomized to highlight the cohort’s distribution above and below the mean of a normal population. Note that these factors were tested in the regression model as continuous variables, not as subgroups. Breastfeeding is dichotomized (“none” versus “any”), rather than reported in number of months, due to the small number of mothers in the cohort who breastfed (n=16). No mothers reported use of recreational drugs during pregnancy, including alcohol, smoking or narcotics use.

Table 3. Association of Potential Confounding Factors with TCAM Scores.

| TCAM Fluency Standard Score |

TCAM Originality Standard Score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Mean (SD) | P-Value | Mean (SD) | P-Value |

| Across Drug Groups | 42 | 91.9 (16.4) | 0.0006† | 97.3 (15.8) | 0.14† |

| Gender | 0.53 | 0.78 | |||

| 1 | 23 | 92.7 (14.7) | 97.9 (15.8) | ||

| 2 | 18 | 91.0 (18.7) | 96.5 (16.1) | ||

| Breast Feeding | 0.08 | 0.05 * | |||

| Missing | 3 | 79.0 (14.1) | 85.5 (4.9) | ||

| None | 23 | 88.1 (15.8) | 93.7 (13.7) | ||

| Any | 16 | 97.3 (15.4) | 103.9 (17.4) | ||

| Pregnancy Vitamins | 0.40 | 0.58 | |||

| Missing | 3 | 79.0 (14.1) | 85.5 (4.9) | ||

| No Folate | 10 | 87.7 (16.8) | 95.5 (16.9) | ||

| Folate Alone | 5 | 99.8 (19.9) | 104.6 (16.5) | ||

| Prenatal with Folate | 24 | 92.0 (15.0) | 97.5 (15.7) | ||

| Pregnancy Risks | 0.90 | 0.88 | |||

| None | 12 | 94.0 (11.3) | 98.5 (13.2) | ||

| Not of Concern | 8 | 90.3 (19.7) | 99.3 (18.2) | ||

| 1 of Concern | 15 | 91.2 (17.8) | 97.3 (18.0) | ||

| >1 of Concern | 7 | 88.1 (16.9) | 93.0 (13.9) | ||

| Seizure Type | 0.82 | 0.99 | |||

| Partial | 26 | 90.2 (15.6) | 97.0 (16.7) | ||

| General | 14 | 92.5 (18.4) | 97.7 (15.6) | ||

| GTCS | 2 | 96.5 (2.1) | 98.5 (4.9) | ||

| Maternal IQ (WAIS) | 0.09 | 0.07 | |||

| <100 | 13 | 86.5 (15.3) | 92.8 (12.1) | ||

| ≥100 | 28 | 93.4 (16.2) | 99.4 (17.0) | ||

| DAS - GCA | 0.03 * | 0.02 * | |||

| Low (<100) | 14 | 89.1 (18.1) | 94.7 (16.3) | ||

| High (≥100) | 22 | 94.7 (16.3) | 100.0 (14.7) | ||

P-value for “across drug groups” tests whether the pooled mean for all exposure groups is less than 100, the standardized population mean for this behavioral measure. In this sample, across fetal exposure groups, ability to generate quantity (fluency) of ideas, but not quality of ideas (originality) is significantly lower than the normative sample (TCAM fluency mean=91.9, SD=16.4, p=.0006). All variables, highlighted in gray, are treated as potential confounding factors. The p-values for these variable are based on regression analyses that indicte whether a variable (or its levels) is associated with a difference in TCAM outcome, not including missing values.

An asterisk indicates this difference is significant at the 0.05 level. The “level” or subgrouping for each variable is presented with TCAM mean and standard deviation.

Three variables are significantly associated with differences in TCAM outcomes, denoted by asterisks in Table 3: DAS general cognitive ability (child IQ) with fluency (p=0.03), DAS general cognitive ability with originality (p=0.02), and breastfeeding with originality (p=0.05). Bonferroni correction at 0.05 significance level, corrected for eleven comparisons per TCAM construct (fluency and originality), yields p-value threshold equal to 0.0045. Four tests do not survive this threshold: (1) valproate-carbamazepine Student’s t-test; (2) bivariate regression of breastfed by originality; (3) bivariate regression of child IQ by fluency; and (4) bivariate regression of child IQ by originality. Maternal IQ does not differ across drug groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Summary Data for Maternal IQ.

| All N=42 |

CBZ N=16 |

LTG N=18 |

VPA N=9 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Maternal WAIS | 104.9 (16.8) | 100.2 (17.6) | 110.5 (13.2) | 98.2 (18.5) |

| Maternal TONI | 107.3 (17.9) | 105.5 (19.8) | 108.7 (19.5) | 106.1 (17.9) |

Dose effects were not statistically analyzed due to small sample size per exposure group. However, for the purpose of describing each exposure group’s distribution for TCAM outcomes, median maternal daily dose values were used to partition each AED group into “high dose” and “low dose” subgroups (Table 5). The “high dose” valproate exposure subgroup had lower mean TCAM scores than the “low dose” valproate exposure subgroup for fluency and originality; conversely, the “high dose” carbamazepine and lamotrigine subgroups had higher mean TCAM scores than the “low dose” subgroups.

Table 5. AED Dose with TCAM Outcomes: “High Dose” and “Low Dose” Subgroups for Carbamazepine, Lamotrigine and Valproate.

| TCAM Fluency |

TCAM Originality |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

| Across Drug Exposures | 42 | 91.9 (16.4) | 97.3 (15.8) |

| CBZ (Median=800) | |||

| < Median | 7 | 86.8 (11.5) | 90.7 (6.5) |

| ≥ Median | 9 | 98.7 (19.8) | 103.9 (20.6) |

| LTG (Median=400) | |||

| < Median | 6 | 92.5 (8.4) | 101.0 (13.5) |

| ≥ Median | 11 | 99.1 (15.4) | 104.2 (16.0) |

| VPA (Median=1250) | |||

| < Median | 4 | 83.0 (4.2) | 85.5 (3.1) |

| ≥ Median | 5 | 71.1 (4.5) | 83.2 (3.3) |

To reflect differing dose ranges for each AED in this cohort and in clinical practice, median dose was calculated from reports of Total Daily Dose (TDD): lamotrigine 400 mg; carbamazepine 800 mg; and valproate 1250 mg. These median dose values were used to partition each AED group into “high dose” and “low dose” subgroups. Sample sizes in each subgroup are reported for the purpose of describing each AED’s distribution only.

Discussion

Main Findings

The primary finding from this study suggests that fetal exposure to valproate monotherapy is associated with impaired cognitive fluency and originality compared to fetal exposure to lamotrigine or carbamazepine. These effects are independent of maternal dose, and are not attributed to maternal seizure type, maternal IQ, pregnancy risk factors, folate/vitamin regimen, breastfeeding pass-through effects, child IQ, or child’s gender. A secondary finding is that fetal exposure to valproate is associated with IQ deficits similar to the findings in the complete sample from the NEAD Study [7]. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that valproate is a neurobehavioral teratogen in humans, with pervasive effects for multiple cognitive domains.

Gene-teratogen interactions may significantly account for differences in exposure group outcomes. Both maternal and fetal genotype can affect in utero absorption, metabolism, and receptor binding of a pharmaceutical agent, influencing its teratogenicity. Therefore, some teratogens might affect only a fraction of individuals prenatally-exposed to the antiepileptic drugs in this study due to differences in maternal genomic susceptibility or fetal genomic susceptibility.

The maternal cohort’s intelligence is comparable to the intelligence in a normal, non-epileptic population, with no significant differences among drug groups (Table 5). However, the effects of antiepileptic drugs, seizure activity or underlying brain disease may have interfered with the mothers’ performance on intelligence measures. This study does not control for maternal intelligence with IQ testing on the father or a first-degree relative of the mother.

Brain-Behavior Implications

Although this study is theory-neutral with respect to mechanisms of teratogenesis, these results are compatible with animal studies that implicate valproate as a functional teratogen that impairs cognition or other behavior. At the molecular level, these effects are reported to include neuronal apoptosis during the brain growth spurt [31-34], interference with telencephalic patterning gradients ([35], reduced expression of neurotrophins [31], and alteration of neuronal growth cone morphology [36-38]. Although specific antiepileptic drug interactions with substrates of central nervous system development are poorly understood in humans, antiepileptic drug exposure coincides with sensitive periods that pattern the telencephalon and give rise to the formation of the cerebral cortex. Teratogenesis affecting the neocortex is not limited to third trimester phenomena (i.e. AED-induced neuronal cell death), but may occur during embryonic and fetal development [39] as early as 33 postfertilized days, when the cerebral hemispheres become identifiable[40].

Unlike anatomical malformations, functional deficits (i.e., cognition/behavior) in humans are usually not apparent until later in childhood. A widely used method in neurobehavioral teratology studies is to measure a child’s intelligence (IQ) as a marker of spared or impaired neurodevelopment. However, as more sophisticated tools are available for understanding complex brain-behavior processes, evidence suggests that IQ tests do not comprehensively assay the functional integrity of neocortical regions that mediate the full range of higher-order cognition. For example, human neuroimaging and lesion studies demonstrate that prefrontal lobe damage in adults can compromise performance on tests of fluid intelligence (‘divergent thinking’ tasks) without impairing performance on IQ tests (i.e. ‘convergent thinking’ tasks) [41, 42]. Conversely, posterior parietal lobe damage can impair performance on IQ tests [43].

Behavioral methods that overemphasize IQ outcomes may not provide a comprehensive assay of neocortical pathogenesis, whether localized in prefrontal cortex or distributed among supramodal regions.

Within the context of child development, IQ may insufficiently assess the impact of fetal exposure to teratogens because vulnerable periods of neocortical development are heterochronic, dependent on the regional emergence of cortical structures and functions [44, 45]. Importantly, the prefrontal structures associated with divergent thinking develop relatively late and exhibit a protracted development that continues through adolescence, evinced by regional patterns of myelination [40, 46, 47], regional patterns of glucose metabolism [47-49], regional patterns of synaptogenesis [47, 50], and cortical thickness [45]. Late-term gestation, therefore, is not without risk from maternal-fetal transfer of neuroactive drugs: cortical structures that develop later may be more vulnerable to certain chemical exposures [44].

Limitations

Although the ability to generate novel ideas has not previously been investigated in human teratology studies of AED exposure, a core limitation of this substudy is its small sample size. In a planned effort to preserve statistical power, certain variables that might confound our findings were not included in our analyses, including gestational age, birth weight, early childhood illness history, and maternal mood. A closer look at these variables is needed in future studies.

A second limitation of this study is that it derives its construct validity from psychometric behavioral observations of cognitive fluency and flexibility rather than from biological data collected during novel idea formation. Importantly, the ability to generate multiple ideas per single stimulus - ‘divergent thinking’ - is not tantamount to the complex, distributed process of real-world problem-solving and creativity that integrates multiple cognitive substrates, including analytical ability for abstract reasoning, working memory, domain-specific memory, and attention-interference control. Additionally, it is unknown if psychometric methods for divergent thinking or fluid intelligence, measured in children, has predictive power for creative productivity or fluid intelligence in adulthood [53, 54].

Conclusions

Overall, the results from our study associate prenatal valproate exposure with impaired cognition, with reduced abilities for novel idea-generating processes in children. Although we do not fully understand the physiological mechanisms underlying human creativity or the molecular effects of antiepileptic drugs on the developing brain, a teratogen that compromises the capacity for creative behavior poses a burden for the individual, and may have lifespan implications. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings; to expand these methods to newer AEDs that have not been investigated for cognitive teratogenesis; and to determine if these effects persist in adolescence and adulthood. Understanding the teratogenic effects of commonly used antiepileptic drugs on higher-order cognitive functions will provide insights for identifying potential windows of pathogenesis for specific AEDs, and will promote improved clinical care for women of childbearing age who require AED therapy.

Acknowledgements

The investigators thank the children and families who have generously given their time to participate in our study. The investigators also thank the PIs and study coordinators from the NEAD Study sites who have collaborated with the investigators to obtain local IRB approval and recruit subjects: Gregory Lee, Ph.D. (The Medical College of Georgia), Morris Cohen, Ed.D. (Medical College of Georgia), Page Pennell, M.D. (Emory University), Patricia Penovich, M.D. (The Minnesota Epilepsy Group), Gholam Motamedi, M.D. (Georgetown University), Debra Cantrell, M.D. (Baylor Medical Center), Edward Bromfield, M.D. (Harvard University Brigham and Women’s Hospital), Layne Moore, M.D. (Ohio State University), Joyce Liporace, M.D. (Riddle Memorial Hospital and Thomas Jefferson Hospital), Kore Liow, M.D. (Via Christi Medical Center), Maria Sam, M.D. (Wake Forest University), Michael Privitera, M.D. (University of Cincinnati), Alison Pack, M.D. (Columbia University), and Martha Morrell, M.D. (Columbia University), Eugene Moore, (NEAD Study Project Manager), and Nancy Browning, Ph.D. (The EMMEs Corporation).

Role of the Funding Source.

This study was supported by the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH-NINDS 3RO1-NS038455-06s1), Medical College of Georgia (C-07103859), and Georgetown University Department of Neurology.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement.

Kelly M. McVearry has no conflict of interest and has received research support from NIH NINDS 3RO1-NS038455-06s1, NIH NINDS 2RO1-NS038455-06, Kirschstein National Research Service Award 5 T32 HD0759, and the Medical College of Georgia. John VanMeter has no conflict of interest.

William D. Gaillard has no conflict of interest. Kimford J. Meador has received research support from NIH grants 2RO1-NS38455, R01-NSO31966-11A2, and N01-NS-5-2364, Glaxo SmithKline, EISAI Medical Research, Myriad Pharmaceuticals, Marinus Pharmaceuticals, NeuroPace, SAM Technology, and UCB Pharma. He also serves on the Professional Advisory Board for the Epilepsy Foundation and receives clinical income from EEG procedures and care of neurological patients.

Statement of Study Sponsor’s Role.

The NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Data Safety Management Board (DSMB) has reviewed and made recommendations for the design, data collection, and analyses of the parent NEAD study; they have also reviewed this substudy and manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Meador K. Anatomical and behavioral effects of in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Curr. 2005;5(6):212–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2005.00067.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardinger HH, et al. Verification of the fetal valproate syndrome phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 1988;29(1):171–85. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320290123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christianson AL, Chesler N, Kromberg JG. Fetal valproate syndrome: clinical and neuro-developmental features in two sibling pairs. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36(4):361–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1994.tb11858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meador KJ, et al. In utero antiepileptic drug exposure: fetal death and malformations. Neurology. 2006;67(3):407–12. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000227919.81208.b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meador K. Cognitive deficits from in utero AED exposure. Epilepsy Curr. 2004;4(5):196–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7597.2004.04510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksson K, et al. Children exposed to valproate in utero--population based evaluation of risks and confounding factors for long-term neurocognitive development. Epilepsy Res. 2005;65(3):189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, Clayton-Smith J, Coombs-Cantrell DT, Cohen M, Kalayjian LA, Kanner A, Liporace JD, Pennell PB, Privitera M, Loring DW, NEAD Study Group Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive function at age 3. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009 Apr 16;360(16):1597–605. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaily E, et al. Normal intelligence in children with prenatal exposure to carbamazepine. Neurology. 2004;62(1):28–32. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adab N, et al. Additional educational needs in children born to mothers with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70(1):15–21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adab N, et al. The longer term outcome of children born to mothers with epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(11):1575–83. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.029132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasalam AD, et al. Characteristics of fetal anticonvulsant syndrome associated autistic disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47(8):551–5. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205001076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams PG, Hersh JH. A male with fetal valproate syndrome and autism. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39(9):632–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams G, et al. Fetal valproate syndrome and autism: additional evidence of an association. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43(3):202–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McVearry K, Brost D, VanMeter J, Meador K. Environmental toxicology and risk assessment for autism phenotypes: a prospective study of children exposed in utero to antiepileptic drugs; International Meeting for Autism Researchers; International Society for Autism Researchers: London. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meador KJ, et al. Cognitive/behavioral teratogenetic effects of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;11(3):292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meador KM, Reynolds MW, Crean S, Fahrbach K, Probst C. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published pregnancy registries and cohorts. Epilepsy Res. 2008;81(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weschler D. Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children-III. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, Tx: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weschler D. Weschler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. The Psychological Corporation; Cleveland, OH: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weschler D. Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children-R. 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliot CD. Differential Ability Scales. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2nd edition The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown L. Test of Nonverbal Intelligence-Third Edition. Pro-Ed; Austin, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weschler D. Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale-III. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torrance EP. Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement. Scholastic Testing Service, Inc.; Bensenville: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renzulli J, The Buros Institute of Mental Measurement . The Ninth Mental Measurements Yearbook. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, Nebraska: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis J. In: The Golden Age of Creativity: The U-Shaped Curve of Child Development. AIE, editor. Harvard Graduate School of Education; Cambridge: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis J. Assessing the creative spirit. Harvard Graduate School of Education Alumni Bulletin; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torrance EP. Must pre-primary educational stimulation be incompatible with creative development? In: Williams FE, editor. Creativity at home and in school. Macalaster Creativity Project; St. Paul: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS . JMP IN 5.1.2. SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, North Carolina: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.The SAS Institute, I. SAS Version 9.1. The SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, North Carolina: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Ikonomidou C. Antiepileptic drugs and apoptosis in the developing brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;993:103–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07517.x. discussion 123–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olney JW, et al. Drug-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Brain Pathol. 2002;12(4):488–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bittigau P, et al. Antiepileptic drugs and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(23):15089–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222550499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ikonomidou C, et al. Neurotransmitters and apoptosis in the developing brain. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62(4):401–5. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall AC, et al. Valproate regulates GSK-3-mediated axonal remodeling and synapsin I clustering in developing neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20(2):257–70. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams RS, et al. A common mechanism of action for three mood-stabilizing drugs. Nature. 2002;417(6886):292–5. doi: 10.1038/417292a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimshoni JA, et al. The effects of central nervous system-active valproic acid constitutional isomers, cyclopropyl analogs, and amide derivatives on neuronal growth cone behavior. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(3):884–92. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaltiel G, et al. Specificity of mood stabilizer action on neuronal growth cones. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(3):281–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rallu M, Corbin JG, Fishell G. Parsing the prosencephalon. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(12):943–51. doi: 10.1038/nrn989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Rahilly R, Mèuller F. The embryonic human brain: an atlas of developmental stages. 3rd ed. Wiley-Liss; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. p. ix.p. 358. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duncan J, Burgess P, Emslie H. Fluid intelligence after frontal lobe lesions. Neuropsychologia. 1995;33(3):261–8. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)00124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duncan J, et al. Intelligence and the frontal lobe: the organization of goal-directed behavior. Cognit Psychol. 1996;30(3):257–303. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1996.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gonzalez CL, Whishaw IQ, Kolb B. Complete sparing of spatial learning following posterior and posterior plus anterior cingulate cortex lesions at 10 days of age in the rat. Neuroscience. 2003;122(2):563–71. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rice D, Barone S., Jr. Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):511–33. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaw P, et al. Neurodevelopmental trajectories of the human cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28(14):3586–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5309-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sowell ER, et al. Mapping cortical change across the human life span. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(3):309–15. doi: 10.1038/nn1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dawson G, Fischer KW. Human behavior and the developing brain. Guilford Press; New York: 1994. p. xxiv.p. 568. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chugani HT, Phelps ME. Maturational changes in cerebral function in infants determined by 18FDG positron emission tomography. Science. 1986;231(4740):840–3. doi: 10.1126/science.3945811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chugani HT, Phelps ME. Imaging human brain development with positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med. 1991;32(1):23–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huttenlocher PR, Dabholkar AS. Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1997;387(2):167–78. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971020)387:2<167::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goodman LS, et al. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 11th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2006. p. xxiii.p. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogawski MA, Loscher W. The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of nonepileptic conditions. Nat Med. 2004;10(7):685–92. doi: 10.1038/nm1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gardner H. Creating minds: an anatomy of creativity seen through the lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Gandhi. BasicBooks; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sternberg RJ. Handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, U.K.; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]