Abstract

The molecular clones pSPeiav19 and p19/wenv17 of equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) differ in env and long terminal repeats (LTRs) and produce viruses (EIAV19 and EIAV17, respectively) of dramatically different virulence phenotypes. These constructs were used to generate a series of chimeric clones to test the individual contributions of LTR, surface (SU), and transmembrane (TM)/Rev regions to the disease potential of the highly virulent EIAV17. The LTRs of EIAV19 and EIAV17 differ by 16 nucleotides in the transcriptional enhancer region. The two viruses differ by 30 amino acids in SU, by 17 amino acids in TM, and by 8 amino acids in Rev. Results from in vivo infections with chimeric clones indicate that both LTR and env of EIAV17 are required for the development of severe acute disease. In the context of the EIAV17 LTR, SU appears to have a greater impact on virulence than does TM. EIAV17SU, containing only the TM/Rev region from the avirulent parent, induced acute disease in two animals, while a similar infectious dose of EIAV17TM (which derives SU from the avirulent parent) did not. Neither EIAV17SU nor EIAV17TM produced lethal disease when administered at infectious doses that were 6- to 30-fold higher than a lethal dose of the parental EIAV17. All chimeric clones replicated in primary equine monocyte-derived macrophages, and there was no apparent correlation between macrophage tropism and virulence phenotype.

Equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) is a macrophagetropic lentivirus of horses (42). The virus differs from the feline, simian, and human immunodeficiency viruses (FIV, SIV, and HIV, respectively) in that lymphocytes are not targets of virus replication and that infected animals do not develop severe immunodeficiency (32). Following exposure to the virus, an acute disease episode of relatively short duration generally occurs within 1 week to 1 month. Acute disease is characterized by fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, central nervous system depression, and anorexia (reviewed in references 19 and 41). The acute disease episode is generally mild, but horses will occasionally develop a particularly severe, fatal form of acute disease that is characterized by a high-titer viremia and very high body temperature. Animals recovering from the acute disease episode may enter the chronic or persistent phase of EIA, which is characterized by periodic episodes of clinical illness. Most infected horses gain immunologic control of virus replication, becoming inapparent carriers.

EIAV antigenic and genomic variations have been previously examined at length (1, 3, 6, 17, 18, 21, 23, 24, 33, 35, 39, 40, 45, 46). Studies of env gene variation demonstrate that infected animals maintain the virus as a quasispecies, as has been previously documented for other lentiviruses (17, 18, 23, 24, 26, 34, 35, 45, 46). Accumulation of mutations in specific variable domains of the surface (SU) unit protein allows the virus to evade or escape neutralizing antibodies (14, 15). Genetic variation in other regions of the EIAV genome has also been described previously. We and others have demonstrated the influence of long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences on the growth characteristics of EIAV (25, 31, 36). Genetic analysis of rev during long-term infection suggests that rev variation may influence virus expression, affecting long-term viral persistence (3, 4).

Previous studies of EIAV genetic variation have focused largely on understanding the virus-host interactions that result in chronic disease and viral persistence rather than on defining the determinants of virulence. For the present study, we used infectious molecular clones of EIAV to examine the genetic basis of two very different virulence phenotypes that have been described previously (37, 38). EIAV19 is a virus stock derived from the infectious molecular clone pSPeiav19. EIAV19 replicates in primary fetal equine kidney, equine dermis, and equine monocyte-derived macrophages (eMDM) as well as in the feline embryonic adenocarcinoma and Cf2Th cell lines (38). We have observed that EIAV19 causes no clinical disease, even when administered to ponies at high doses (38).

To generate a genetically defined virulent virus, pSPeiav19 was used as the backbone to produce a set of clones in which env and LTRs were replaced by sequences obtained directly from the highly virulent Wyoming field strain of EIAV (37). One construct, p19/wenv17, has been described previously, and virus derived from this clone (designated EIAV17) causes severe acute disease in our Shetland pony model (37). EIAV17 replicates only in eMDM, a characteristic shared by field strains of EIAV (5). The acute virulence phenotype of EIAV17 is useful for studies in which the availability of experimental animals is limited.

Sequence differences between clones pSPeiav19 and p19/wenv17 are limited to an approximately 2-kb fragment of env and the viral LTRs. Virus stocks derived from both pSPeiav19 and p19/wenv17 replicate to a high titer, with cytopathic effects, in eMDM (37), so it is unlikely that the dramatic difference in their virulence phenotypes is due solely to macrophage tropism. These clones provide an ideal starting point to locate those genes or regions that play major roles in virulence. In this report, we describe the construction and testing of several new infectious molecular clones of EIAV that we have used to determine the contributions of env and LTRs to the virulence phenotype of EIAV17 and demonstrate that both SU and LTRs contain virulence determinants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clone construction.

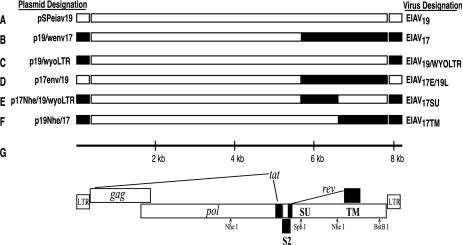

Infectious molecular clones described in this report are depicted in Fig. 1. pSPeiav19 (Fig. 1A), p19/wenv17 (Fig. 1B), and p19/wyoLTR (Fig. 1C) have been described previously (36-38). The new construct p17env/19 (Fig. 1D) contains an env gene fragment from p19/wenv17, but its LTRs are derived from pSPeiav19. p17env/19 was constructed by using a combination of PCR and conventional cloning. PCR was used to generate a 338-bp fragment containing nucleotides (nt) 7910 to 8231 from pSPeiav19 using primers WS1 (5′-TGTGGGGTTTTTATGAGGGG-3′) and 8211R1 (5′-CGCGGTCGACGAATTCTGTAGGATCTCGAACAGAC-3′) (Fig. 2). Primers 7582 (5′-TAAGGACCCTTGGTG-3′) and 91 (5′-GCCTAGCAACATGAGCT-3′) were used to generate a 428-bp fragment (nt 7587 to 8014) from p19/wenv17. The two PCR products overlap by 107 identical nt between the oligonucleotides WS1 and 91. These two products, and primers 8211R1 and 7611 (5′-CCCCCCCCGTCGACGAGATTCGAAGCGAAGG-3′), were used to amplify a 636-bp fragment that places the pSPeiav19 LTR onto the 3′ end of the env region of p19/wenv17. The 636-bp fragment was digested with BstBI and EcoRI and was used to replace the corresponding region from a 2.6-kbp (SphI to EcoRI) fragment of p19/wenv17 (37). The new 2.6-kbp SphI-to-EcoRI fragment was then moved into pSPeiav19 in order to generate p17env/19.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of clones and the EIAV genome. (A through G) Open boxes represent the sequence of pSPeiav19 (GenBank accession number U01866 [38]). Solid black boxes represent sequences derived from the Wyoming field strain that were used to generate the p19/wenv17 clone (GenBank accession number AF028232 [37]). Plasmid designations are shown to the left of each construct; virus designations are shown to the right. Panel G shows the relative positions of EIAV open reading frames. The restriction enzyme sites used to generate new clones are indicated.

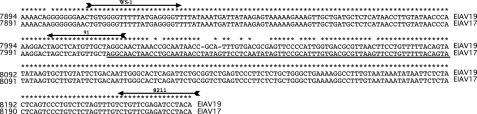

FIG. 2.

EIAV19 and EIAV17 LTR sequences. The underlined region is the transcriptional enhancer. The sequence differences in this region result in the presence of a unique set of transcription factor binding sites for each virus; similar EIAV LTRs have been previously described and mapped by others (28, 29). The arrows represent oligonucleotide primers used in PCR to facilitate the construction of p19/wyoLTR. The numbering scheme is based on the position of the 3′ LTR from clones pSPeiav19 and p19wenv/17.

To construct p17Nhe1/19/wyoLTR (Fig. 1E), we started with p19/wyoLTR (36), which had been digested with NheI to remove a 2.79-kbp pol-env fragment (Fig. 1G). The corresponding NheI fragment was isolated from p19/wenv17 and ligated to the prepared vector. The two NheI fragments share sequences from the 5′ NheI site through the SphI site but differ from the SphI site to the 3′ NheI site; thus, the NheI fragment swap effectively places the SphI-to-3′-NheI fragment from p19/wenv17 onto the p19/wyoLTR background. Clone p19Nhe/17 (Fig. 1F) derives sequences from the 3′ NheI site through the 3′ LTR from p19/wenv17. This plasmid was prepared by starting with clone p19/wenv17, removing its 2.79-kb NheI fragment, and replacing it with the corresponding NheI fragment from pSPeiav19. All clones were analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion and partial DNA sequence analysis in order to check that the desired genetic swaps and replacements were present. All clones were constructed and maintained in a derivative of the low-copy-number vector pLG338 (10).

Virus stocks.

To generate infectious virus, plasmid DNA was used to transfect D17 cells (ATCC CCL-183) by using a calcium phosphate transfection kit (Invitrogen) as described previously (37), and culture supernatants were collected at 24, 48, and 72 h. Culture supernatants were tested for the presence of reverse transcriptase (RT), as described previously (13), using [3H]TTP in place of [32βP]TTP. One-milliliter aliquots of D17 cell supernatants were passed onto eMDM to generate virus stocks. The eMDM were recovered and maintained as described previously (44).

The 50% infective dose (ID50) for eMDM was also determined for each virus stock. Cells were plated in poly-d-lysine-coated 12-well dishes (BD Biosciences), infected 4 days postplating, and maintained for 11 days postinfection (p.i.). Virus was concentrated from culture supernatants by centrifugation; the presence of virus was determined by RT assay. RT values of greater than three times that of uninfected control cultures were considered positive for virus growth.

To serve as another indicator of viral infectivity, a real-time Taqman PCR assay was used to determine the provirus copy numbers in eMDM at 24 h p.i. Cells were lysed, and total DNA was purified by using a QIAmp tissue kit (Qiagen). A Taqman real-time PCR assay was performed on a Bio-Rad Icycler machine as follows. Each 50-μl reaction contained 1× reaction buffer (Applied Biosystems) without MgCl2, 5.5 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 0.3 μM upstream primer (5′-TTCCCATGACAGCAAGGTTT-3′), 0.3 μM downstream primer (5′-TCCATTGTCTATATGTCTGCCTAAA-3′), 0.07 μM Taqman probe (5′-FAM-CAAAAGCAGGCTCCATCTGTCTTTCTCTAGGACT-TAMRA-3′), 5 to 10 μg of DNA template or water control, and 1.25 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems). Cycling parameters were 95°C for 30 s and 58°C for 1 min (40 cycles). DNA standards consisted of pSPeiav19 plasmid DNA at 102 to 106 molecules per reaction in duplicate. Cell DNA samples were analyzed in duplicate, and real-time data were analyzed by using Bio-Rad Icycler software.

Animal studies.

Animal studies complied with all relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies. Virus stocks were used to infect Shetland ponies as previously described (37). Animals inoculated with the following virus stocks received a virus dose of 2 × 105 counts per minute (cpm) of RT activity: EIAV17E/19L, EIAV19/WYOLTR, and EIAV17TM. EIAV17SU was inoculated at a dose of 105 cpm of RT activity.

Rectal temperatures of infected animals were monitored twice daily. Blood samples were obtained pre- and postinfection for determination of complete blood counts. Disease episodes were defined as periods of increased body temperature. Blood and serum samples were collected to quantify virus, to monitor the development of antiviral antibody, and for recovery of viral genomes. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect a transmembrane peptide was performed by using a commercial assay (obtained from Centaur, Inc.). Agar gel immunodiffusion assays were performed as described previously (9). Viral genome fragments were amplified from blood samples collected within 2 weeks p.i., cloned, and sequenced to confirm the identity of the infecting virus stocks.

RESULTS

In previous studies, we demonstrated a difference in the ability of EIAV19 and EIAV17—derived from two infectious molecular clones, pSPeiav19 and p19/wenv17, respectively—to produce disease in Shetland ponies. EIAV19 fails to produce clinical symptoms, even when administered to ponies at doses of up to 106 cpm of RT activity (38). In contrast, EIAV17, which contains env and LTR sequences derived from the Wyoming field strain of EIAV, induces severe disease by two weeks p.i. when administered at 10- to 20-fold-lower doses (37). As illustrated in Fig. 1, these two clones share approximately 5.4 kb of sequence, differing only in their LTRs (Fig. 2) and env/rev regions (Fig. 3). Regions in common include gag, pol, tat, S2, and the amino terminus of env. The shared env region has a length of 438 bp, encompassing the first 146 amino acids of the env open reading frame and the first coding exon of rev. To further investigate the genetic region(s) responsible for the different virulence phenotypes, we constructed additional clones combining defined regions of the pSPeiav19 and p19/wenv17 genomes.

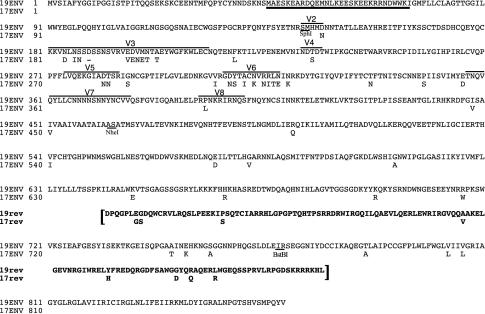

FIG. 3.

SU, TM, and Rev amino acid comparisons. The EIAV19 sequence is shown above; EIAV17 residues that differ are shown below. V2 through V8 indicate previously defined variable regions of EIAV SU (24). The approximate positions of the SphI and NheI restriction enzymes used to construct EIAV17SU and EIAV17TM are shown. Coding exon 1 of rev is in the same reading frame as SU and is shown by the heavy underline. Exon 2 of rev is in an alternate reading frame, and the translation is shown in the bracketed region.

Contribution of env and LTR sequences to virulence phenotype.

We first assayed the individual contributions of the Wyoming-derived LTR and env sequences to the virulence phenotype of EIAV17. We constructed p17env/19 (Fig. 1D), which contains two complete LTRs from the avirulent clone pSPeiav19 in combination with the env region from the virulent p19/wenv17. Figure 2 shows the primers used in a PCR strategy to facilitate the LTR replacement. The EIAV19 LTR was swapped for the EIAV17 LTR in an identical region of 107 bp that begins just 3′ to the polypurine tract. The two LTRs differ at 16 positions that fall within the enhancer region in U3 (Fig. 2) and confer changes in previously mapped transcription factor binding sites (28, 29). As shown in Table 1, EIAV17E/19L, derived from clone p17env/19, replicates in eMDM to produce a virus stock with RT activity equivalent to that of the parental EIAV17 virus. When tested in vivo, EIAV17E/19L failed to produce a febrile episode during the first 45 days p.i. (Fig. 4B); however, the infected animal seroconverted by day 18 p.i. While only one animal was inoculated with EIAV17E/19L, the virus dose (as determined by RT activity) was twofold higher than the dose of EIAV17 that produced severe disease episodes (requiring euthanasia) in two animals (Fig. 4A). We recently determined ID50 titers in eMDM for each of the virus stocks tested in animals (Table 1). By this criterion, EIAV17E/19L was administered at an infectious dose that was 2.5-fold higher than the lethal dose of EIAV17, suggesting that the Wyoming-derived LTR makes an important contribution to the virulence phenotype of EIAV17.

TABLE 1.

Maximum titers and relative infectivity of virus stocks

| Virus designation | Maximum RT titer (cpm/ml) | Relative ID50 per cpma | Relative provirus copy no. per cpmb | Pony inoculum (cpm) | Relative infectious virus dose administered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIAV17 | 105.0 | 1 | 1 | 5 × 104 | 0.5 |

| EIAV17 | 105.0 | 1 | 1 | 105 | 1 |

| EIAV19/WYOLTR | 104.9 | 0.1 | ND | 2 × 105 | 0.2c |

| EIAV17E/19L | 105.0 | 1.25 | ND | 2 × 105 | 2.5c |

| EIAV17SU | 104.6 | 30 | 16 | 105 | 16-30d |

| EIAV17TM | 104.8 | 10 | 3 | 2 × 105 | 6-20d |

The ID50 per cpm for the EIAV17 virus stock was 2.

In a single experiment, the provirus copy numbers per cpm were 580 (±560), 9,000 (±3,600), and 1,660 (±640) for EIAV17, EIAV17SU, and EIAV17TM, respectively.

Based upon ID50 determination.

Range is based on ID50 and provirus copy number determinations.

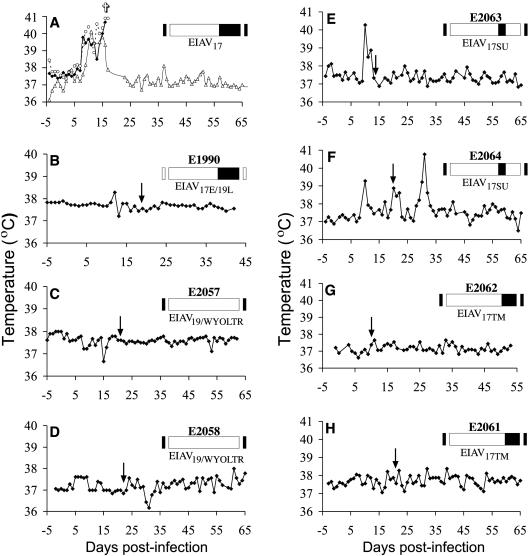

FIG. 4.

Clinical profiles. (A) EIAV17-infected ponies. The infecting doses for ponies 38059 (○) and 29987 (♦) were 105 cpm of RT activity; pony 29990 (▵) was infected with 5 × 104 cpm of the same EIAV17 virus stock (37). Ponies 29987 and 38059 were euthanized at 17 and 18 days p.i., respectively. (B) E1990 was infected with an eMDM culture supernatant containing 2 × 105 cpm of RT activity of EIAV17E/19L. Body temperature remained normal for 45 days p.i. The arrow indicates the day of seroconversion as determined by ELISA. (C and D) Ponies E2057 and E2058 were infected with eMDM culture supernatants containing 2 × 105 cpm of RT activity of EIAV19/WYOLTR. Body temperatures remained normal for 65 days p.i. with no other clinical abnormalities noted. Arrows indicate the days of seroconversion as determined by agar gel immunodiffusion assay. (E and F) Ponies E2063 and E2064 were infected with 105 cpm of RT activity of EIAV17SU. (G and H) Ponies E2062 and E2061 were infected with 2 × 105 cpm of RT activity of EIAV17TM. In panels E and F, elevated body temperatures indicate febrile episodes that are typical of EIAV infection. Days of seroconversion (as determined by ELISA) are indicated by arrows.

Clone p19/wyoLTR (Fig. 1C) derives its LTRs from the virulent parent p19/wenv17 and derives its env/rev sequences from the avirulent parent pSPeiav19, as described previously (36). As shown in Table 1, EIAV19/WYOLTR, derived from clone p19/wyoLTR, replicates in eMDM to produce virus stocks with RT activity equivalent to that of EIAV17. EIAV19/WYOLTR was used to infect two animals, whose clinical profiles are shown in Fig. 4C and D. The animals seroconverted at 19 and 21 days p.i., but neither experienced a febrile episode for the first 100 days p.i. A third animal infected with EIAV19/WYOLTR also failed to exhibit clinical symptoms and did not seroconvert until approximately 50 days p.i. (data not shown). EIAV19/WYOLTR was administered to ponies at twice the lethal dose (as measured by RT activity) of EIAV17; however, the ID50 per cpm of this virus stock is approximately 10-fold less than that of the EIAV17 stock. By this criterion, the infecting dose in each of three animals was approximately 2.5-fold lower than a dose of EIAV17 that induced acute clinical disease; however, none of the EIAV19/WYOLTR-infected animals developed even mild clinical disease. The combined results from these four infections strongly suggest that both the Wyoming-derived LTRs and the Wyoming-derived env gene each contribute to the virulence phenotype of EIAV17.

Contribution of SU and TM sequences to virulence phenotype.

EIAV17 and EIAV19 differ by 30 amino acids in SU and 17 amino acids in TM, as shown in Fig. 3. Therefore, we next examined the relative contribution of SU versus that of the TM/rev region to the virulence phenotype of EIAV17. We constructed p17Nhe/19/wyoLTR and p19Nhe/17, which contain only the SU or only the TM/Rev region from the virulent parent, respectively (Fig. 1). Both constructs derive LTRs from the virulent parent and share common gag, pol, tat, and S2 sequences with both parents. The virus derived from p17Nhe/19/wyoLTR (designated EIAV17SU) shares amino acids 147 to 444 of SU with EIAV17. Note that the first 438 bp of SU is shared by both the virulent and avirulent parents and that this region encodes the first 146 amino acids of SU as well as the first coding exon of rev (Fig. 3). The first 19 amino acids of TM of EIAV17SU are also derived from the virulent parent, while the remainder of TM and the second coding exon of rev are from the avirulent parent. EIAV17SU was used to infect Shetland ponies (results shown in Fig. 4E and F). Both ponies experienced acute febrile episodes. Pony E2063 had a single febrile episode at days 10 to 12 p.i. The febrile episode resolved, and the animal maintained a normal body temperature for the next 2 months. Pony E2064 also experienced acute disease but with somewhat different characteristics. A day of elevated body temperature was recorded on day 10 p.i. and again at day 20 p.i. A more notable and extended febrile episode occurred at days 30 to 32 p.i. The body temperature then remained normal through the next 75 days p.i. While disease episodes were observed, it should be noted that they were less severe than those previously observed in ponies receiving EIAV17 (Fig. 4A) (37); note also that the infecting dose of EIAV17SU, as determined by two different infectivity assays (ID50 and initial provirus copy number), was up to 30-fold greater than that of the EIAV17 parent (Table 1).

EIAV17TM (from construct p19Nhe/17 [Fig. 1F]) shares amino acids 20 to 417 of TM and shares its overlapping rev sequences with virulent EIAV17. The clinical profiles of two animals infected with this virus are presented in Fig. 4G and H. These animals seroconverted at 10 and 21 days p.i., similar to the results observed for EIAV17SU-infected animals, but body temperatures remained normal for more than 50 days p.i. Results of infectivity assays show that at an inoculum of 2 × 105 cpm of RT activity, the ponies received 6- to 20-fold more infectious virus (as measured on eMDM by ID50 and provirus copy number) relative to the lethal dose of EIAV17. This finding indicates that the TM/rev region alone is not sufficient to account for the observed virulence phenotype of EIAV17. By all criteria used to determine the titer of our virus stocks, both EIAV17SU and EIAV17TM were administered to ponies at doses equivalent to or higher than the lethal dose of EIAV17, yet neither induced acute febrile episodes requiring euthanasia.

DISCUSSION

We generated a series of infectious molecular clones of EIAV in order to map the major virulence determinants of this lentivirus. Our focus was to identify genetic regions that influence the development and/or severity of acute disease. These studies were facilitated by the availability of genetically related clones (pSPeiav19 and p19/wenv17) that produce viruses (EIAV19 and EIAV17) carrying different virulence phenotypes. The parental viruses and all of the new chimeric viruses replicate in eMDM with cytopathic effects. The RT titers of the new virus constructs were generally comparable to those of the parental clones (Table 1). Pony inocula were based upon RT activity; however, we subsequently determined minimal infectivity titers of the stocks used for the infections. ID50s per cpm were determined by using primary eMDM from a single donor animal. Unfortunately, the life span of eMDM under our standard culture conditions is limited to approximately 3 weeks, an experimental endpoint that might not allow adequate comparison of viruses with similar infectivity but different replication kinetics. To attempt to address this possibility, we performed a single experiment in which provirus copy numbers present at 24 h p.i. were determined by real-time PCR. As shown in Table 1, the relative amount of provirus at 24 h p.i. per cpm of inoculum paralleled the ID50s per cpm for EIAV17, EIAV17SU, and EIAV17TM. With one exception (EIAV19/WYOLTR), the ID50s of the tested viruses were equivalent to or greater than that of the parental EIAV17 virus. Since none of the chimeric viruses produced disease severity equivalent to that produced by EIAV17, it is clear that the ability to replicate in eMDM per se is not a helpful indicator of the potential for the development of severe acute disease by EIAV.

Our in vivo assays consisted of using a small number of experimental animals and performing infections with high doses of virus. Using these parameters, we showed that both the env and LTRs derived from the Wyoming field strain were required for the virulence phenotype of EIAV17. Replacement of either the Wyoming-derived LTRs or env with those of the avirulent strain yielded a virus that caused no acute disease in our experimental system. EIAV17 and EIAV17E/19L differ only in their LTR sequence and display dramatically different virulence phenotypes. The two LTRs have multiple sequence differences that alter transcription factor binding motifs (Fig. 2). Detailed descriptions of EIAV LTR sequences similar to those in the present study have been reported previously (28, 29), but to our knowledge, direct in vivo comparisons of these two LTRs have not been described. We have previously demonstrated that the Wyoming LTR neither drives transcription of a reporter gene construct nor supports virus replication in fibroblasts (36). This finding explains the selection of variant LTRs (similar to the EIAV19 LTR) during adaptation to growth in fibroblasts. It has also been shown that most field strains of EIAV have LTRs that closely resemble the Wyoming strain consensus and that there is little LTR variation when virus containing a Wyoming-like LTR is examined over time in vivo (26). Finally, Wyoming-like LTRs emerge in horses infected with culture-adapted virus stocks (35). These data strongly suggest that Wyoming-like LTR sequences are favored in vivo. Remaining unclear are the critical interactions between viral LTR and host cell that favor the Wyoming LTR in vivo and allow for disease expression from EIAV17 but not EIAV17E/19L. A higher expression level in vivo in circulating monocytes or tissue macrophages may lead to an increased virus burden in the infected animal; however, an in vitro difference in replicative ability is not apparent. Alternatively, the EIAV17 LTR might facilitate virus replication in cells other than monocytes and macrophages, and this ability may contribute to the virulence phenotype. In this regard, Maury et al. (30) previously demonstrated the replication of EIAV in primary equine endothelial cells. Replication efficiency was strain dependent, with three of four different strains replicating in umbilical cord and renal artery endothelial cells. Interestingly, the Wyoming strain of EIAV was the one tested strain that failed to replicate in these cells (30). It is also possible that subtle but important differences in the regulation of virus expression in vivo are affected by the LTR sequence. Future fine-structure mapping studies of the EIAV LTR will be necessary in order to define the contributions of specific transcription factor binding motifs to the virulence phenotype of EIAV17.

The LTR sequence is not the sole virulence determinant of EIAV17; the Wyoming-derived env gene also contributes to its virulence phenotype. Forty-seven amino acid differences are found in the env regions EIAV17 and EIAV19. Thirty of these are located in SU; 17 differences are found in TM. Rev sequences differ by eight amino acids in the second coding exon. To delineate the differences that exert the highest impact on virulence, we chose to examine env in the context of the Wyoming-derived LTR. Using a convenient NheI restriction enzyme site, we generated EIAV17SU, which derives SU, and the first 19 amino acids of TM, from the virulent parent. Due to the method of generating EIAV17, EIAV17SU shares most of TM and all of its rev sequences with the avirulent parent. A high dose of EIAV17SU caused acute disease in our two test animals. However, the disease was not as severe as animals infected with EIAV17 (37), even though the EIAV17SU inocula, as determined by ID50, were severalfold greater than those of EIAV17. This finding strongly suggests that the presence of TM/rev sequences from the avirulent parent attenuates the overall virulence phenotype.

There are 30 amino acid differences in SU between the avirulent virus, EIAV19, and both of the acutely virulent viruses (EIAV17 and EIAV17SU). The clones contain very divergent V3 sequences. V3 is the principal neutralizing domain (PND) of EIAV (2) and is a region of extensive sequence variation in vivo (23, 24, 35, 45, 46). Both insertions and deletions in the EIAV PND are common, and viruses that totally lack the PND have been recovered previously (24). EIAV17 and EIAV19 also differ in the previously defined V4 through V6 regions of SU (24). V4 is a short variable region of five amino acids (NDTDT in EIAV19 and NDSDT in EIAV17). Both viruses have a potential N-linked glycosylation site in V4, and it seems unlikely that the T-to-S substitution would play a major role in the virulence phenotype. The V5 region of EIAV has been defined as a 10-amino-acid sequence (24). The V5 sequence of EIAV17, but not that of EIAV19, contains a potential N-linked glycosylation site. Examination of V5 from animals monitored during experimental infections reveals that V5 frequently contains an N-linked glycosylation site, though its position within the domain may vary (23, 24, 46).

EIAV17 and EIAV19 also diverge extensively in the V6 region of SU, where they differ by 8 of 13 amino acids (positions 308 to 320). A functionally equivalent substitution of V to I occurs near V6, at position 305, and two functionally equivalent amino acid substitutions occur within V6 (Y309S and A311I). A striking difference in V6 between EIAV19 and EIAV17 is the presence in EIAV17 of two potential N-linked glycosylation sites that are generated by a D-to-N substitution at position 308 and by R-to-N and L-to-T substitutions at positions 314 and 317. Examination of this region in persistently infected animals shows a number of N-linked glycosylation sites in the V6 region that varies from 0 to 2 (23, 45, 46). The two clones have similar V7 sequences and differ in V8 by one amino acid.

The evolution of the V3 and V4 regions of EIAV SU have been previously linked to the development of neutralization resistance phenotypes during long-term infection (17), and a neutralizing monoclonal antibody has been mapped to V5 (2)—strong indications that these regions evolve in response to immune pressures. The V6 region of EIAV SU has not yet been demonstrated to play a role in virus neutralization, as no neutralizing antibodies to this region have been identified (17); however, only a limited number of such antibodies have been tested. There is presently little information regarding specific functions of various SU domains. For example, cellular receptors and/or coreceptors for EIAV have not been identified, and no direct effects of purified EIAV SU on cell function or disease processes have been reported. While the present study suggests a role for SU in the development of acute disease, additional studies are required so as to clarify its role in disease expression.

Both of the acutely virulent viruses (EIAV17 and EIAV17SU) also share the first 20 amino acids of TM. This region differs between the virulent and avirulent viruses at two positions (I4V and I7V) that lie in the fusion peptide of EIAV TM (based on similarity to SIV and HIV TM proteins). As these substitutions do not alter the hydrophobic nature of the domain, it would be surprising if they played a major role in the virulence phenotype of EIAV17.

EIAV17TM shares amino acids 20 to 417 of TM (and the second coding exon of rev) with the virulent EIAV17. Virus derived from EIAV17TM failed to cause an acute febrile episode in either of two infected animals, suggesting that TM/Rev is not solely responsible for the virulence phenotype of EIAV17. Our results do suggest a role for TM/Rev in virulence, however, as EIAV17SU is less virulent than is the EIAV17 parent. Comparison of the TM sequences between the avirulent and acutely virulent viruses reveals 17 amino acid differences. None of the amino acid substitutions in TM change the position or number of N-linked glycosylation sites, and hot spots for variation in TM have not been noted.

The role of env sequences in lentivirus virulence has been clearly demonstrated in simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV)-infected rhesus macaques (7, 8, 11, 12, 16, 20, 22, 27, 43). As few as 12 amino acid differences in the env sequence are sufficient to change pathogenic potential of SHIV clones (43). Most of the env changes that arise with increased virulence are localized to gp120 variable regions; changes in the number and position of N-linked glycosylation sites are common (7, 8, 16, 27, 43). Some measurable differences in virulent SHIVs that have been attributed to env sequence changes include fusogenicity, resistance to neutralization, and increased replicative potential (7, 8, 43). During the present study, we determined that infectivity of EIAV for eMDM is not a reliable indicator of virulence. However, we have not yet compared the replication kinetics of our virus stocks. In addition, the development of acute disease generally occurs prior to the development of a detectable immune response; thus, resistance to neutralization is unlikely to play a role in this process. The possibility that other env-mediated biologic differences correlate with virulence is currently under investigation.

All of the EIAV clones in this study are identical in the first coding exon of rev, which specifies the nuclear export sequence. However there are eight amino acid differences between EIAV19 and EIAV17 in the second coding exon of rev (Fig. 3). Belshan et al. (3, 4) analyzed the rev quasispecies present over time in a horse infected with the Wyoming strain of EIAV. EIAV17 rev is very similar (differing by only one amino acid, E37G) to the predominant rev sequence in infectious Wyoming virus stocks (3). This rev sequence was present during the acute febrile episode, was not recovered during chronic disease, and then reappeared during a long afebrile period (3). In contrast, the rev of EIAV19 is similar to rev variants that predominated during late-stage inapparent carrier infection (800 days p.i.). Both the virulent and avirulent clones thus contain rev sequences that have been found in a natural infection but that may confer a different replication potential or phenotype to the virus.

We are continuing to examine the role of env in EIAV virulence by generating additional molecular clones and by monitoring env evolution in rapid-passage experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant number CA-59278 from the National Cancer Institute (to S.L.P. and F.J.F).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexandersen, S., and S. Carpenter. 1991. Characterization of variable regions in the envelope and S3 open reading frame of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 65:4255-4262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball, J. M., K. E. Rushlow, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1992. Detailed mapping of the antigenicity of the surface unit glycoprotein of equine infectious anemia virus by using synthetic peptide strategies. J. Virol. 66:732-742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belshan, M., P. Baccam, J. L. Oaks, B. A. Sponseller, S. C. Murphy, J. Cornette, and S. Carpenter. 2001. Genetic and biological variation in equine infectious anemia virus Rev correlates with variable stages of clinical disease in an experimentally infected pony. Virology 279:185-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belshan, M., M. E. Harris, A. E. Shoemaker, T. J. Hope, and S. Carpenter. 1998. Biological characterization of Rev variation in equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 72:4421-4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benton, C. V., B. L. Brown, J. S. Harshman, and R. V. Gilden. 1981. In vitro host range of equine infectious anemia virus. Intervirology 16:225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter, S., S. Alexandersen, M. J. Long, S. Perryman, and B. Chesebro. 1991. Identification of a hypervariable region in the long terminal repeat of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 65:1605-1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cayabyab, M., G. B. Karlsson, B. A. Etemad-Moghadam, W. Hofmann, T. Steenbeke, M. Halloran, J. W. Fanton, M. K. Axthelm, N. L. Letvin, and J. G. Sodroski. 1999. Changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins responsible for the pathogenicity of a multiply passaged simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-HXBc2). J. Virol. 73:976-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakrabarti, L. A., T. Ivanovic, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 2002. Properties of the surface envelope glycoprotein associated with virulence of simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIV(SF33A) molecular clones. J. Virol. 76:1588-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coggins, L., N. L. Norcross, and S. R. Nusbaum. 1972. Diagnosis of equine infectious anemia by immunodiffusion test. Am. J. Vet. Res. 33:11-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham, T. P., R. C. Montelaro, and K. E. Rushlow. 1993. Lentivirus envelope sequences and proviral genomes are stabilized in Escherichia coli when cloned in low-copy-number plasmid vectors. Gene 124:93-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etemad-Moghadam, B., D. Rhone, T. Steenbeke, Y. Sun, J. Manola, R. Gelman, J. W. Fanton, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, M. K. Axthelm, N. L. Letvin, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Membrane-fusing capacity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope proteins determines the efficiency of CD4+ T-cell depletion in macaques infected by a simian-human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 75:5646-5655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etemad-Moghadam, B., Y. Sun, E. K. Nicholson, M. Fernandes, K. Liou, R. Gomila, J. Lee, and J. Sodroski. 2000. Envelope glycoprotein determinants of increased fusogenicity in a pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-KB9) passaged in vivo. J. Virol. 74:4433-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregersen, J. P., H. Wege, L. Preiss, and K. D. Jentsch. 1988. Detection of human immunodeficiency virus and other retroviruses in cell culture supernatants by a reverse transcriptase microassay. J. Virol. Methods 19:161-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammond, S. A., S. J. Cook, D. L. Lichtenstein, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1997. Maturation of the cellular and humoral immune responses to persistent infection in horses by equine infectious anemia virus is a complex and lengthy process. J. Virol. 71:3840-3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammond, S. A., F. Li, B. M. McKeon, Sr., S. J. Cook, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 2000. Immune responses and viral replication in long-term inapparent carrier ponies inoculated with equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 74:5968-5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann-Lehmann, R., J. Vlasak, A. L. Chenine, P. L. Li, T. W. Baba, D. C. Montefiori, H. M. McClure, D. C. Anderson, and R. M. Ruprecht. 2002. Molecular evolution of human immunodeficiency virus env in humans and monkeys: similar patterns occur during natural disease progression or rapid virus passage. J. Virol. 76:5278-5284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howe, L., C. Leroux, C. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 2002. Equine infectious anemia virus envelope evolution in vivo during persistent infection progressively increases resistance to in vitro serum antibody neutralization as a dominant phenotype. J. Virol. 76:10588-10597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain, K. A., C. J. Issel, K. L. Schnorr, P. M. Rwambo, and R. C. Montelaro. 1987. Antigenic analysis of equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) variants by using monoclonal antibodies: epitopes of glycoprotein gp90 of EIAV stimulate neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 61:2956-2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issel, C. J., and L. Coggins. 1979. Equine infectious anemia: current knowledge. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 174:727-733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlsson, G. B., M. Halloran, D. Schenten, J. Lee, P. Racz, K. Tenner-Racz, J. Manola, R. Gelman, B. Etemad-Moghadam, E. Desjardins, R. Wyatt, N. P. Gerard, L. Marcon, D. Margolin, J. Fanton, M. K. Axthelm, N. L. Letvin, and J. Sodroski. 1998. The envelope glycoprotein ectodomains determine the efficiency of CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion in simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Exp. Med. 188:1159-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim, C. H., and J. W. Casey. 1992. Genomic variation and segregation of equine infectious anemia virus during acute infection. J. Virol. 66:3879-3882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaBonte, J. A., T. Patel, W. Hofmann, and J. Sodroski. 2000. Importance of membrane fusion mediated by human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins for lysis of primary CD4-positive T cells. J. Virol. 74:10690-10698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leroux, C., J. K. Craigo, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 2001. Equine infectious anemia virus genomic evolution in progressor and nonprogressor ponies. J. Virol. 75:4570-4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leroux, C., C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1997. Novel and dynamic evolution of equine infectious anemia virus genomic quasispecies associated with sequential disease cycles in an experimentally infected pony. J. Virol. 71:9627-9639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lichtenstein, D. L., J. K. Craigo, C. Leroux, K. E. Rushlow, R. F. Cook, S. J. Cook, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1999. Effects of long terminal repeat sequence variation on equine infectious anemia virus replication in vitro and in vivo. Virology 263:408-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichtenstein, D. L., C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1996. Genomic quasispecies associated with the initiation of infection and disease in ponies experimentally infected with equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 70:3346-3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, Z. Q., S. Muhkerjee, M. Sahni, C. McCormick-Davis, K. Leung, Z. Li, V. H. Gattone II, C. Tian, R. W. Doms, T. L. Hoffman, R. Raghavan, O. Narayan, and E. B. Stephens. 1999. Derivation and biological characterization of a molecular clone of SHIV(KU-2) that causes AIDS, neurological disease, and renal disease in rhesus macaques. Virology 260:295-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maury, W. 1994. Monocyte maturation controls expression of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 68:6270-6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maury, W., S. Bradley, B. Wright, and R. Hines. 2000. Cell specificity of the transcription-factor repertoire used by a lentivirus: motifs important for expression of equine infectious anemia virus in nonmonocytic cells. Virology 267:267-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maury, W., J. L. Oaks, and S. Bradley. 1998. Equine endothelial cells support productive infection of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 72:9291-9297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maury, W., S. Perryman, J. L. Oaks, B. K. Seid, T. Crawford, T. McGuire, and S. Carpenter. 1997. Localized sequence heterogeneity in the long terminal repeats of in vivo isolates of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 71:4929-4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montelaro, R. C., J. M. Ball, and K. E. Rushlow. 1993. Equine retroviruses, p. 257-360. In L. J. A. (ed.), The Retroviridae, vol. 2. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 33.Montelaro, R. C., B. Parekh, A. Orrego, and C. J. Issel. 1984. Antigenic variation during persistent infection by equine infectious anemia virus, a retrovirus. J. Biol. Chem. 259:10539-10544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pang, H., X. G. Kong, H. Sentsui, Y. Kono, T. Sugiura, A. Hasegawa, and H. Akashi. 1997. Genetic variation of envelope gp90 gene of equine infectious anemia virus isolated from an experimentally infected horse. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 59:1089-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Payne, S. L., F. D. Fang, C. P. Liu, B. R. Dhruva, P. Rwambo, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1987. Antigenic variation and lentivirus persistence: variations in envelope gene sequences during EIAV infection resemble changes reported for sequential isolates of HIV. Virology 161:321-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payne, S. L., K. La Celle, X. F. Pei, X. M. Qi, H. Shao, W. K. Steagall, S. Perry, and F. Fuller. 1999. Long terminal repeat sequences of equine infectious anaemia virus are a major determinant of cell tropism. J. Gen. Virol. 80:755-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Payne, S. L., X. M. Qi, H. Shao, A. Dwyer, and F. J. Fuller. 1998. Disease induction by virus derived from molecular clones of equine infectious anemia virus. J. Virol. 72:483-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payne, S. L., J. Rausch, K. Rushlow, R. C. Montelaro, C. Issel, M. Flaherty, S. Perry, D. Sellon, and F. Fuller. 1994. Characterization of infectious molecular clones of equine infectious anaemia virus. J. Gen. Virol. 75:425-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payne, S. L., K. Rushlow, B. R. Dhruva, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1989. Localization of conserved and variable antigenic domains of equine infectious anemia virus envelope glycoproteins using recombinant env-encoded protein fragments produced in Escherichia coli. Virology 172:609-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Payne, S. L., O. Salinovich, S. M. Nauman, C. J. Issel, and R. C. Montelaro. 1987. Course and extent of variation of equine infectious anemia virus during parallel persistent infections. J. Virol. 61:1266-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sellon, D. C., F. J. Fuller, and T. C. McGuire. 1994. The immunopathogenesis of equine infectious anemia virus. Virus Res. 32:111-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sellon, D. C., S. T. Perry, L. Coggins, and F. J. Fuller. 1992. Wild-type equine infectious anemia virus replicates in vivo predominantly in tissue macrophages, not in peripheral blood monocytes. J. Virol. 66:5906-5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Si, Z., M. Cayabyab, and J. Sodroski. 2001. Envelope glycoprotein determinants of neutralization resistance in a simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2) derived by passage in monkeys. J. Virol. 75:4208-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whetter, L., D. Archambault, S. Perry, A. Gazit, L. Coggins, A. Yaniv, D. Clabough, J. Dahlberg, F. Fuller, and S. Tronick. 1990. Equine infectious anemia virus derived from a molecular clone persistently infects horses. J. Virol. 64:5750-5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng, Y. H., T. Nakaya, H. Sentsui, M. Kameoka, M. Kishi, K. Hagiwara, H. Takahashi, Y. Kono, and K. Ikuta. 1997. Insertions, duplications and substitutions in restricted gp90 regions of equine infectious anaemia virus during febrile episodes in an experimentally infected horse. J. Gen. Virol. 78:807-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng, Y. H., H. Sentsui, T. Nakaya, Y. Kono, and K. Ikuta. 1997. In vivo dynamics of equine infectious anemia viruses emerging during febrile episodes: insertions/duplications at the principal neutralizing domain. J. Virol. 71:5031-5039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]