Abstract

Microbial secondary metabolites are a potent source of antibiotics and other pharmaceuticals. Genome mining of their biosynthetic gene clusters has become a key method to accelerate their identification and characterization. In 2011, we developed antiSMASH, a web-based analysis platform that automates this process. Here, we present the highly improved antiSMASH 2.0 release, available at http://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/. For the new version, antiSMASH was entirely re-designed using a plug-and-play concept that allows easy integration of novel predictor or output modules. antiSMASH 2.0 now supports input of multiple related sequences simultaneously (multi-FASTA/GenBank/EMBL), which allows the analysis of draft genomes comprising multiple contigs. Moreover, direct analysis of protein sequences is now possible. antiSMASH 2.0 has also been equipped with the capacity to detect additional classes of secondary metabolites, including oligosaccharide antibiotics, phenazines, thiopeptides, homo-serine lactones, phosphonates and furans. The algorithm for predicting the core structure of the cluster end product is now also covering lantipeptides, in addition to polyketides and non-ribosomal peptides. The antiSMASH ClusterBlast functionality has been extended to identify sub-clusters involved in the biosynthesis of specific chemical building blocks. The new features currently make antiSMASH 2.0 the most comprehensive resource for identifying and analyzing novel secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways in microorganisms.

INTRODUCTION

Many microorganisms produce secondary metabolites with interesting bioactivities, including antibiotics, anti-cancer agents and many other drugs (1).

For decades, the only way to identify and characterize such bioactive secondary metabolites involved a labor- and time-consuming procedure: one had to isolate new bacterial or fungal strains, cultivate them under different conditions, identify, isolate, purify and test any bioactive molecules that were produced and perform a complete chemical structure elucidation. The rapidly decreasing cost of whole-genome sequencing technologies enables new approaches that can greatly accelerate this process using bioinformatics analysis of the genome sequences of potential producer strains (2–4), before or in parallel with the biological/chemical isolation process. The fact that the biosynthetic pathways for many secondary metabolites are encoded by highly modular compact gene clusters facilitates this kind of analysis (5,6).

In recent years, many individual algorithms have been developed that cover specific steps in the bioinformatics analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis based on microbial genome sequences [for review (7,8)]. For example, ClustScan (9), CLUSEAN (10), SBSPKS (11) and SMURF (12) are tools for the identification and/or analysis of the enzymatic domains in multi-modular polyketide synthases and/or non-ribosomal peptide synthetases, which are the key enzymes for the synthesis of the largest classes of clinically important secondary metabolites. These include, e.g. non-ribosomal peptide antibiotics like penicillin and polyketide macrolides like the immunosuppressant tacrolimus. NRPSpredictor (13,14), NRPSSP (15) and the PKS/NRPS predictive BLAST Server (16) are sophisticated tools for the prediction of substrate specificities of key biosynthetic steps, allowing an approximate prediction of the chemical structure of bioactive end compounds based on the genome sequence (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of the capabilities of various software tools for the analysis of biosynthetic gene clusters

| Features | antiSMASH 2.0 | antiSMASH 1.0 | CLUSEAN | SMURF | ClustScan | NaPDoS | NP.searcher | NRPSpredictor2 | NRPSSP | SBSPKS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open-source and stand-alone available | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Covers bacteria, archaea and fungi | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| NRPS/PKS detection | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| NRPS/PKS detailed functional domain annotation | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| NRP/PK core structure prediction | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Lantipeptide core structure prediction | X | |||||||||

| Detection of other biosynthetic classes | X | X | X | |||||||

| Gene cluster border prediction | X | X | X | |||||||

| Comparative gene cluster analysis | X | X | ||||||||

| Sub-cluster analysis | X | |||||||||

| Prediction of putative novel gene cluster types | X | X | ||||||||

| Protein sequence input | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Nucleotide sequence input | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Multi-contig input | X | X | ||||||||

| PKS structural modeling | X | |||||||||

| NRPS/PKS domain phylogenomic analysis | (X)a | X |

antiSMASH 2.0 combines by far the most functionalities into a single framework and adds four key new features compared with antiSMASH 1.0. The phylogenomic analysis embedded in NaPDoS can be accessed through direct links from the relevant C and KS domains shown in the antiSMASH output page.

aSupport for NRPS/PKS phylogenomic analysis via NaPDoS cross-reference.

In 2011, we released the first version of the ‘antibiotics and secondary metabolite analysis shell’ (antiSMASH), a web server and stand-alone software, which combines automated identification of secondary metabolite gene clusters in genome sequences with a large collection of compound-specific analysis algorithms (17). Within the past two years, antiSMASH has become the standard tool to analyze genomes of bacteria and fungi for their potential to produce secondary metabolites. Since the start of the service, the stand-alone software has been downloaded >3200 times, and >28 000 antiSMASH jobs have been submitted to the antiSMASH web server; the monthly data volume currently processed is >12 Gb. antiSMASH also supports the manual PKS/NRPS cluster curation effort of the ClusterMine360 database (18) by providing a standardized annotation basis.

Here, we present version 2.0 of antiSMASH. The software has been entirely restructured internally, and it now uses a plug-and-play concept for easier maintainability and extensibility. A number of novel cluster detection and analysis features have been added to cover the broadest possible range of secondary metabolite classes. Finally, the web-based user interface was completely re-designed for better usability and a wider range of possible input files, allowing, e.g. the analysis of unassembled draft genomes and metagenomic sequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Implementation of new features

The basic steps of an antiSMASH analysis have been described by Medema et al. (17): first, potential biosynthetic gene clusters are identified by comparing each gene product encoded on the uploaded DNA sequence against a manually curated collection of profile hidden Markov models (pHMMs). These pHMMs describe key biosynthetic enzymes of the 24 secondary metabolite classes detectable by antiSMASH, using the HMMer3 software (19). Key enzymes encoded in each gene cluster are assigned to secondary metabolite-specific clusters of orthologous groups (smCOGs). Depending on the class of the detected secondary metabolite gene cluster, further detailed analyses are performed: the domains of multimodular polyketide synthases (PKSs) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) are identified by a pHMM-based approach. Specificities of enzymes are determined by analyzing active site residues using integrated third-party algorithms and tools, such as the methods of Minowa et al. (20) and NRPSpredictor2 (14) for the prediction of NRPS adenylation domain specificities. Based on these data, a core chemical structure of the putative biosynthesis product is generated and displayed. In addition, an integrated version of MultiGeneBlast (21), ClusterBlast, is used to identify similar gene clusters in a comprehensive gene cluster database. antiSMASH 2.0 can be either installed locally on Windows, Mac OS X or Linux computers, or be accessed via the internet at http://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org (recommended). The use of the antiSMASH web server is free of charge and does not require registration or login data. Voluntarily, the users can provide an email address, which is used to send information and the link of the results, once the computing of the antiSMASH 2.0 results is finished. The data are stored on the server for 30 days and are deleted afterward.

Although the general strategy of antiSMASH has not changed in version 2.0, many improvements have been implemented in the new version, which we outline here.

New file and input options

antiSMASH 2.0 now makes it easier to work with draft genomes consisting of a large number of individual sequence records: support has been added for multi-GenBank, multi-EMBL, as well as multi-FASTA files. If the NCBI download option yields a whole-genome shotgun (WGS) master or supercontig record, antiSMASH 2.0 will download all constituent single WGS records from NCBI as well and combine all of them into a single output (Figure 1). For prokaryotic FASTA inputs, antiSMASH 2.0 now also offers the option to perform the initial search for gene cluster signature genes on all open reading frames of >60 nt throughout all six translation frames of a nucleotide sequence, before running the standard gene prediction with Glimmer. This avoids that mistakes in the gene prediction stage lead to false negatives in the gene cluster prediction stage. After the gene prediction stage, all open reading frames that match to pHMMs in the antiSMASH pHMM library are retained in the gene cluster output, even if they were not predicted as genes by Glimmer.

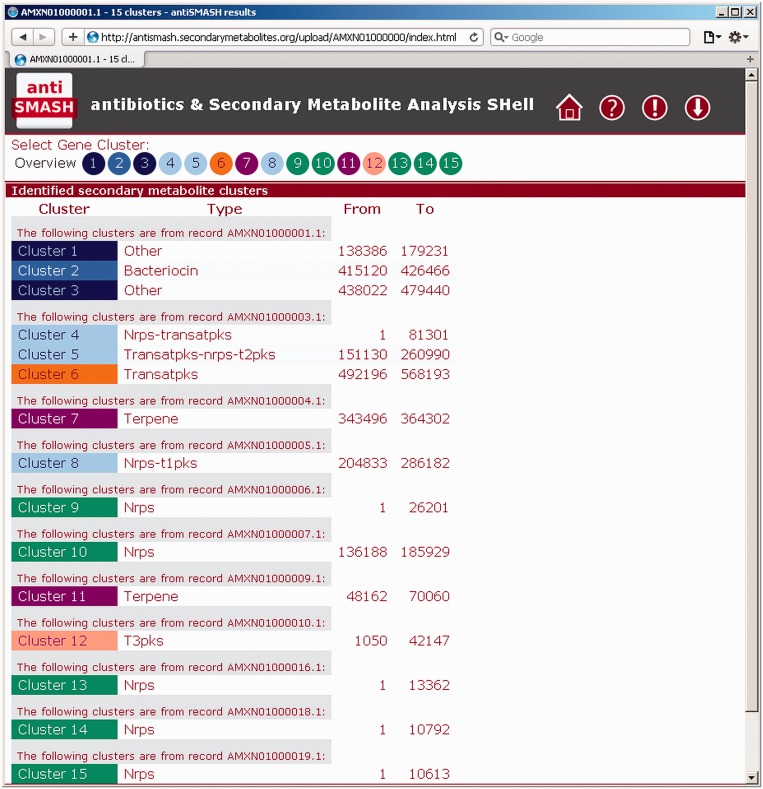

Figure 1.

Overview page of the antiSMASH results. antiSMASH 2.0 gives an overview of all the output results in a single page, showing all the detected biosynthetic gene clusters with their type classifications and nucleotide positions. For inputs consisting of multiple entries/contigs, the clusters are separated by input entry/contig. Gene cluster types are signified by specific colors.

In addition to nucleotide sequences, antiSMASH 2.0 can now also be used to analyze PKS, NRPS and lantipeptide precursor amino acid sequences directly: their protein sequences can either be analyzed by specifying their NCBI GenPept accession numbers or by pasting the FASTA sequences directly into an input field.

Detection of secondary metabolite gene clusters in sequence data

In addition to the secondary metabolite cluster types supported in the original release of antiSMASH (type I, II and III polyketides, non-ribosomal peptides, terpenes, lantipeptides, bacteriocins, aminoglycosides/aminocyclitols, β-lactams, aminocoumarins, indoles, butyrolactones, ectoines, siderophores, phosphoglycolipids, melanins and a generic class of clusters encoding unusual secondary metabolite biosynthesis genes), version 2.0 adds support for oligosaccharide antibiotics, phenazines, thiopeptides, homoserine lactones, phosphonates and furans. The cluster detection uses the same pHMM rule-based approach as the initial release (17): in short, the pHMMs are used to detect signature proteins or protein domains that are characteristic for the respective secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathway. Some pHMMs were obtained from PFAM or TIGRFAM. If no suitable pHMMs were available from these databases, custom pHMMs were constructed based on manually curated seed alignments (Supplementary Table S1). These are composed of protein sequences of experimentally characterized biosynthetic enzymes described in literature, as well as their close homologs found in gene clusters from the same type. The models were curated by manually inspecting the output of searches against the non-redundant (nr) database of protein sequences. The seed alignments are available online at http://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org/download.html#extras. After scanning the genome with the pHMM library, antiSMASH evaluates all hits using a set of rules (Supplementary Table S2) that describe the different cluster types. Unlike the hard-coded rules in the initial release of antiSMASH, the detection rules and profile lists are now located in editable TXT files, making it easy for users to add and modify cluster rules in the stand-alone version, e.g. to accommodate newly discovered or proprietary compound classes without code changes. The results of gene cluster predictions by antiSMASH are continuously checked on new data arising from research performed throughout the natural products community, and pHMMs and their cut-offs are regularly updated when either false positives or false negatives become apparent.

The profile-based detection of secondary metabolite clusters has now been augmented by a tighter integration of the generalized PFAM (22) domain-based ClusterFinder algorithm (Cimermancic et al., in preparation) already included in version 1.0 of antiSMASH. This algorithm performs probabilistic inference of gene clusters by identifying genomic regions with unusually high frequencies of secondary metabolism-associated PFAM domains, and it was designed to detect ‘classical’ as well as less typical and even novel classes of secondary metabolite gene clusters. While antiSMASH 1.0 only generated the output of this algorithm in a static image, version 2.0 displays these additional putative gene clusters along with the other gene clusters in the HTML output. A key advantage of this is that these putative gene clusters will now also be included in the subsequent (Sub)ClusterBlast analyses.

Metabolite-specific detection modules

antiSMASH version 2.0 adds lantipeptide-specific chemical core structure analysis to the existing set of NRPS/PKS core prediction tools. If one or more open reading frames encoding putative lantipeptide prepropeptides are found, antiSMASH predicts the core peptide molecular mass and sequence after leader peptide cleavage. The leader peptide cleavage motifs are identified via pHMMs specific for cleavage sites of class I–IV lantipeptides, respectively. The best-matching profile determines the classification of the prepropeptide, and the cleavage site is calculated from the pHMM-sequence alignment.

To obtain the core peptide mass, all serine and threonine residues in the core peptide are assumed to be dehydrated to didehydro-alanine (Dha) and didehydro-butyrine (Dhb), the most frequent post-translational modification in lantipeptides. Reported masses are the monoisotopic masses of the most prevalent isotopomers. The number of lanthionine/methyl-lantionine bridges is calculated from the number of cysteine, Dha and Dhb residues available for bridge formation (Blin et al., in preparation).

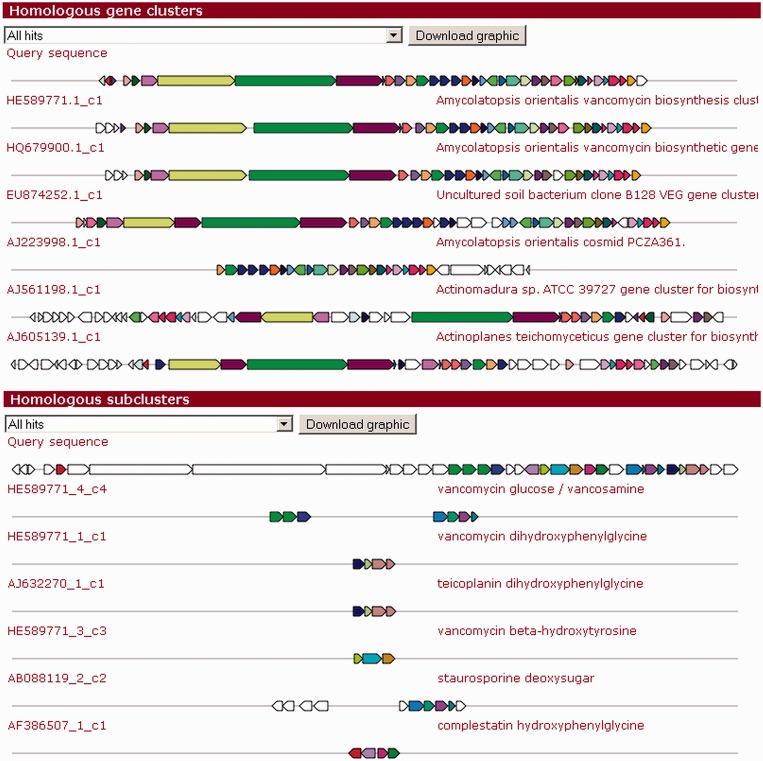

SubclusterBlast

Extending the ClusterBlast analysis that identifies homologous gene clusters across many published genome sequences, we have added a new option to identify operons related to the biosynthesis of precursors or specific chemical moieties in a gene cluster’s end product. This new analysis module, SubclusterBlast, performs blastp searches of the amino acid translations of all cluster genes against a database containing 126 sub-clusters from gene clusters encoding known compounds (Figure 2). These sub-clusters code for the biosynthesis of precursors, such as 6-methylsalicylic acid, 3-amino-5-hydroxybenzoic acid, ethylmalonyl-CoA, deoxysugars and hydroxyphenylglycine, which are highly specific for certain classes of bioactive compounds. Hence, their presence in a genome allows more confident conclusions about the biosynthetic capacities of an organism. The hits are sorted in the same way as the ClusterBlast hits (17), but they are gathered with stricter thresholds: a minimal percentage identity of 45% and a minimal sequence coverage of 40% are required. The highest-scoring sub-cluster hits are then displayed on the results page using an annotated vector graphic similar to the general ClusterBlast output.

Figure 2.

ClusterBlast and SubclusterBlast outputs for the balhimycin (23) biosynthesis gene cluster. The top six hits of each analysis module are shown. The ClusterBlast module shows the homology between the balhimycin gene cluster and the vancomycin, VEG, A40926 and teicoplanin biosynthesis gene clusters. Homologous genes are shown in identical colors, whereas white-colored genes have no BLAST hits between the gene clusters. The novel SubclusterBlast module can identify homologous sub-clusters encoding the biosynthesis of specific chemical moieties. In this case, SubclusterBlast is able to identify the dihydroxyphenylglycine (dHpg), hydroxyphenylglycine (Hpg) and hydroxytyrosine (Bht) precursor biosynthesis sub-clusters, as well as the vancosamine-like sugar biosynthesis sub-cluster.

Output and visualization

When antiSMASH has finished the computation of an analysis, it now provides an overview table that displays all identified secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters with links to the respective prediction details, as a convenient starting point for further analysis (Figure 1). For nucleotide inputs consisting of multiple GBK/EMBL/FASTA entries, the results are separated per entry. Because of the large size of the antiSMASH results webpage in version 1.0, loading took a long time and sometimes even caused timeout error messages in the user’s web browser. Therefore, the visualization component of antiSMASH 2.0 was completely re-designed, resulting in a reduction of transfer data volume and greatly accelerated display, even for results containing many cluster hits.

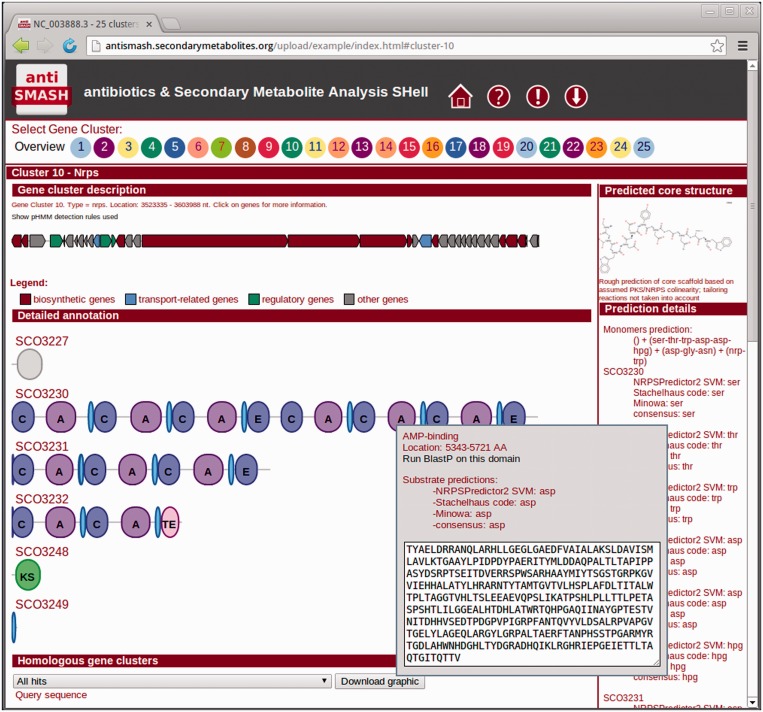

The overall layout of the interactive results page has been retained (Figure 3): in the top section, the identified clusters are displayed as circles that serve as direct links to the clusters. In antiSMASH 2.0, the circles are color coded depending on the class of the identified cluster to ease navigation by the user. The individual cluster result pages are now reachable via the result URL, making it possible to both bookmark and direct other people to specific cluster pages. Individual cluster result pages contain an interactive graphical representation of the genes identified in the cluster. Again, color coding was added to represent the functional classes of the gene cluster genes according to an smCOG-based classification: biosynthesis, transport, regulation or other. For modular enzymes (NRPS, PKS) or lantipeptides, detailed annotation sections provide information on the domain organization and the putative cleavage sites and molecular weights, respectively. At the bottom of the page, graphical representations of the ClusterBlast results and—if available—the SubclusterBlast results are displayed. For several classes of antibiotics, where the analysis of the gene clusters allows the prediction of core structures of the biosynthetic products, a predicted structure and detailed information on the prediction source are displayed in a box on the right side of the results page (Figure 3). For lantipeptides and NRPS products, there is a direct link to the NORINE (24) peptide database. The information displayed on the interactive webpage is also annotated in EMBL- or GenBank-formatted sequence files, which can be downloaded and used with standard sequence analysis software. In addition, an archive containing all data including the webpage can be saved for later use.

Figure 3.

Top part of a gene cluster overview in the re-designed antiSMASH 2.0 output. The gene cluster shown is the calcium-dependent antibiotic biosynthesis gene cluster from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). The gene cluster-type–specific coloring of the numbered gene cluster buttons makes it easier to navigate through large result files. smCOG-based coloring of biosynthetic, transport-related and regulatory genes within the gene cluster make it easier to interpret the architecture of the gene cluster.

Plug-and-play architecture

In antiSMASH 2.0, the software architecture has been completely re-designed to make it easily extendable: the core program reads in ‘analysis plug-ins’ that are either general or specific to a certain gene cluster type ‘output plug-ins’ facilitate the output of the results to HTML, GBK, EMBL, TXT and XLS files. To make it easy for users to customize antiSMASH for their own analyses, we provide a plug-in template from the download section of http://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org, which can be used to design custom plug-ins, e.g. for reading user-specific input formats or analyzing novel cluster types.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

With options to upload DNA sequences of both finished genomes and draft sequences, to make antiSMASH download published sequences from NCBI and to analyze amino acid sequences directly, antiSMASH 2.0 now covers all common types of input data. For draft genome data published in the NCBI genome database, antiSMASH can automatically download the records specified in the WGS summary record. As a test for the downloader, the recently published Oxytricha trifallax WGS record (Genbank accession no. AMCR00000000.1) consisting of 22 363 contigs was run via the internet interface, and the server handled the large amount of contigs and sequence data (67 Mb) without issues. For prokaryotic genome sequences, draft genome support increases the number of genomes that can be processed directly via NCBI accession numbers from 2570 to 8898, a ∼2.5-fold increase of available sequences. One important caveat should be noted: when analyzing draft genomes, the number of detected gene clusters reported by antiSMASH can be artificially high because gene clusters can be fragmented across multiple contigs, and antiSMASH detects all fragments as separate gene clusters. On the other hand, some contigs with gene cluster fragments might be left undetected, if the subset of genes present on a contig does not suffice to match the criteria for gene cluster detection by antiSMASH.

antiSMASH 2.0 now supports 24 secondary metabolite cluster types via profile-based detection of their core biosynthetic genes (up from 19). In test runs on 28 known gene clusters encoding compounds of the newly added classes, all of them were detected successfully (Supplementary Table S3). To assess the general accuracy of the antiSMASH predictions, we selected the same test set of genomes as for the original version (17): the genomes of the proteobacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 (25), the actinomycetes Streptomyces griseus IFO 13350 (26), Kitasatospora setae NBRC 14216T (27) and Salinispora tropica CNB-440 (28) and the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus Af293 (29) were analyzed with antiSMASH 2.0 and compared with the manually identified clusters referred to in the original publications. In all, 97.3% of clusters (108 of 111) that were assigned manually were also identified by antiSMASH 2.0. This is the same performance as with antiSMASH 1.0, which was expected, as the established cluster finding algorithm has not changed in version 2.0. In addition to the 35 clusters that were predicted by antiSMASH 1.0 but were missed in the original publications, four additional clusters were identified by the new detection modules of antiSMASH 2.0, increasing the percentage of newly found gene clusters from 31.5 to 35.1% (Supplementary Table S4).

If further extension of the prediction ability is desired, new profiles can be added easily and without changes to the core code of the software using the new plug-and-play architecture of antiSMASH 2.0. The new version can also cast a wider net than the original version, by using improved ways to exploit the outputs of the ClusterFinder inclusive search algorithm for putative clusters (Cimermancic et al., in preparation). Although the inclusive algorithm is likely to identify too many clusters, the combination with homology search methods allows focusing on the ones with homology to previously identified secondary metabolite clusters.

A major goal of antiSMASH 2.0 was to increase usability. Because antiSMASH 1.0 loaded all the results simultaneously when loading/opening the HTML output file, it was slow for the typical large results files: e.g. loading the 35 cluster results for Streptomyces tsukubaensis NRRL18488 (Genbank accession no. AJSZ01000001) from a local hard drive took ∼40 s on a fast PC. In contrast, antiSMASH 2.0 output for the same data now loads in <2 s, even though more clusters (37) are detected. The reduced result page size has the added benefit of being accessible from smart phones and tablets (tested for iOS and Android).

antiSMASH 2.0 is currently the most comprehensive software for genome mining and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways, and it includes or provides direct links to the most significant other tools and algorithms for this task. The updates to the antiSMASH framework will enable it to be successfully used with the latest sequencing technologies and biochemical insights, whereas it will continue to be a key tool for state-of-the-art synthetic biology approaches towards secondary metabolism (23).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables 1–4 and Supplementary References [30,31].

FUNDING

German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) [0315585A to T.W.]; German Centre for Infection Research (DZIF) [8000-402-2 to T.W.]; Dutch Technology Foundation STW, which is the applied science division of NWO, and the Technology Programme of the Ministry of Economic Affairs [STW 10463 to E.T.]; NWO-Vidi fellowship (to R.B.). Funding for open access charge: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and Open Access Publishing Fund of Tübingen University.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford JM, Clardy J. Microbial genome mining answers longstanding biosynthetic questions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:7589–7590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205361109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheffler RJ, Colmer S, Tynan H, Demain AL, Gullo VP. Antimicrobials, drug discovery, and genome mining. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013;97:969–978. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4609-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zotchev SB, Sekurova ON, Katz L. Genome-based bioprospecting of microbes for new therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012;23:941–947. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medema MH, Breitling R, Bovenberg R, Takano E. Exploiting plug-and-play synthetic biology for drug discovery and production in microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:131–137. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medema MH, van Raaphorst R, Takano E, Breitling R. Computational tools for the synthetic design of biochemical pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:191–202. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber T. In silico tools for the analysis of antibiotic biosynthetic pathways. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.02.001. (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fedorova ND, Moktali V, Medema MH. Bioinformatics approaches and software for detection of secondary metabolic gene clusters. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;944:23–45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-122-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starcevic A, Zucko J, Simunkovic J, Long PF, Cullum J, Hranueli D. ClustScan: an integrated program package for the semi-automatic annotation of modular biosynthetic gene clusters and in silico prediction of novel chemical structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6882–6892. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber T, Rausch C, Lopez P, Hoof I, Gaykova V, Huson DH, Wohlleben W. CLUSEAN: a computer-based framework for the automated analysis of bacterial secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters. J. Biotechnol. 2009;140:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand S, Prasad MV, Yadav G, Kumar N, Shehara J, Ansari MZ, Mohanty D. SBSPKS: structure based sequence analysis of polyketide synthases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W487–W496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khaldi N, Seifuddin FT, Turner G, Haft D, Nierman WC, Wolfe KH, Fedorova ND. SMURF: Genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2010;47:736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rausch C, Weber T, Kohlbacher O, Wohlleben W, Huson DH. Specificity prediction of adenylation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) using transductive support vector machines (TSVMs) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5799–5808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Röttig M, Medema MH, Blin K, Weber T, Rausch C, Kohlbacher O. NRPSpredictor2—a web server for predicting NRPS adenylation domain specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W362–W367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prieto C, Garcia-Estrada C, Lorenzana D, Martin JF. NRPSsp: non-ribosomal peptide synthase substrate predictor. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:426–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachmann BO, Ravel J. Chapter 8. Methods for in silico prediction of microbial polyketide and nonribosomal peptide biosynthetic pathways from DNA sequence data. Methods Enzymol. 2009;458:181–217. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medema MH, Blin K, Cimermancic P, de Jager V, Zakrzewski P, Fischbach MA, Weber T, Takano E, Breitling R. antiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W339–W346. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conway KR, Boddy CN. ClusterMine360: a database of microbial PKS/NRPS biosynthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D402–D407. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eddy SR. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minowa Y, Araki M, Kanehisa M. Comprehensive analysis of distinctive polyketide and nonribosomal peptide structural motifs encoded in microbial genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;368:1500–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medema MH, Takano E, Breitling R. Detecting sequence homology at the gene cluster level with MultiGeneBlast. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:1218–1223. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelzer S, Süßmuth RD, Heckmann D, Recktenwald J, Huber P, Jung G, Wohlleben W. Identification and analysis of the balhimycin biosynthetic gene cluster and its use for manipulating glycopeptide biosynthesis in Amycolatopsis mediterranei DSM5908. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1565–1573. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caboche S, Pupin M, Leclere V, Fontaine A, Jacques P, Kucherov G. NORINE: a database of nonribosomal peptides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D326–D331. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paulsen IT, Press CM, Ravel J, Kobayashi DY, Myers GS, Mavrodi DV, DeBoy RT, Seshadri R, Ren Q, Madupu R, et al. Complete genome sequence of the plant commensal Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nbt1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohnishi Y, Ishikawa J, Hara H, Suzuki H, Ikenoya M, Ikeda H, Yamashita A, Hattori M, Horinouchi S. Genome sequence of the streptomycin-producing microorganism Streptomyces griseus IFO 13350. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:4050–4060. doi: 10.1128/JB.00204-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ichikawa N, Oguchi A, Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Kitani S, Watanabe Y, Nakamura S, Katano Y, Kishi E, Sasagawa M, et al. Genome sequence of Kitasatospora setae NBRC 14216T: an evolutionary snapshot of the family Streptomycetaceae. DNA Res. 2010;17:393–406. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Udwary DW, Zeigler L, Asolkar RN, Singan V, Lapidus A, Fenical W, Jensen PR, Moore BS. Genome sequencing reveals complex secondary metabolome in the marine actinomycete Salinispora tropica. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10376–10381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700962104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nierman WC, Pain A, Anderson MJ, Wortman JR, Kim HS, Arroyo J, Berriman M, Abe K, Archer DB, Bermejo C, et al. Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature. 2005;438:1151–1156. doi: 10.1038/nature04332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yadav G, Gokhale RS, Mohanty D. Towards prediction of metabolic products of polyketide synthases: an in silico analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5:e1000351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Jong A, van Heel AJ, Kok J, Kuipers OP. BAGEL2: mining for bacteriocins in genomic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W647–W651. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]