Abstract

Ghost cells have been a topic of controversy since a long time. The appearance of these cells in different lesions has given it varying terms. In lesions like that of Calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor (CCOT), these cells have been termed as ‘Ghost cells’ whereas similar descriptive cells have been called shadow/translucent cells in non-odontogenic lesions like Craniopharyngiomas of the pituitary gland and Pilomatricomas of skin. Controversy arises because of the fact that there are varying opinions and incomplete knowledge about their origin, nature, significance and relation in different neoplasms. Irrespective of the origin, these cells are seen in odontogenic and non-odontogenic neoplasms, which probably direct us towards a missing link between these differing neoplasms. This article attempts to present a review on the concepts around these peculiar cells and shed some light on these ghosts that are still in dark.

Keywords: Craniopharygioma, ghost cell, notch pathway, odontogenic cyst, odontogenic tumor, pilomatricoma, shadow cell, wnt pathway

INTRODUCTION

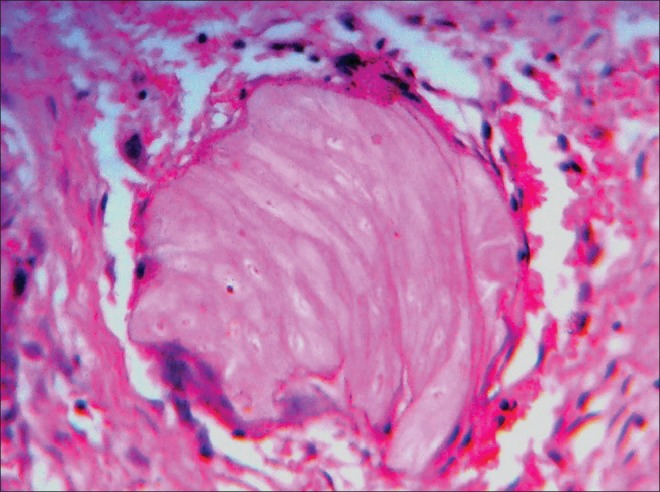

“Ghost cells” have a shadowy appearance in hematoxylin-eosin stained sections-and hence the name. These epithelial cells are recognized as swollen, pale, eosinophilic cells. They are seen either singly or in sheets with a clear conservation of basic cellular outline (if not fully coalesced), generally with apparent clear areas or with some remnants indicative of the site previously occupied by the nucleus [Figure 1]. These cells lack nuclear and cytoplasmic details and are characteristically seen in calcifying cystic odontogenic tumors (CCOT), craniopharyngiomas and pilomatricomas. Other rarer entities reportedly exhibiting ghost cells include odontomas, dentinogenic ghost cell tumors, dentinogenic ghost cell carcinomas, odontoameloblastomas, ameloblastic-fibrodontomas, pilomatrical carcinoma and few visceral tumors. Few neoplasms, which rarely reveal ghost cells, include ameloblastomas and clear cell odontogenic carcinomas. Sedano and Pindborg[1] believed that such cells are also present in inner enamel epithelium of a normal developing human tooth and eruption cysts respectively.

Figure 1.

Ghost cells with clear conservation of basic cellular outline but lacking nuclear and cytoplasmic details.(Ref.: Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, MCODS, Mangalore, India)

Ghost cells are also characterized by their tendency to induce granulomas, potential to calcify and resistance to resorption.[2,3]

HISTORY OF GHOST CELLS

The earliest description of ghost cells has been cited in 1936, by Highman and Ogden.[4] in their initial definitive description of pilomatricomas. They described ghost cells as dyskeratotic cells which are similar to viable cells but have distinct outline. They criticized the term degeneration or necrosis for these cells as their form and coherence were retained. Similarly, Hashimoto,[5] et al. found a gradual increase in keratinization from basaloid cells to shadow cells and considered these cells as in an advanced stage of keratinization.

In 1962, Gorlin,[6] et al. suggested the sequence of events in the development of CCOT (Until 2005, CCOT was named as Calcifying odontogenic cyst) and the ghost cells. During the development of CCOT, the transformation of an odontogenic epithelial cell into a ghost cell firstly starts by enlargement of mural cells (towards cystic cavity), followed by other epithelial cells in cystic lining into abnormally keratinized cells. The basal cells transform towards the end and this transformation leads to loss of distinction between epithelium and connective tissue. Since ghost cells are abnormally keratinized they are considered as foreign bodies if they reach the connective tissue.[7] This theory was supported by Abrams and Howell.[8]

Ghost cells were discovered late in Odontomas because of their histological resemblance to poorly decalcified osteodentin. The possible pathogenesis of ghost cells in Odontomas, as speculated by Levy,[9] et al. (1973) was from metaplastic transformation of odontogenic epithelium which occurs due to reduced oxygen supply caused by walling-off effect by the surrounding hard tissue calcification. When this continues, it can cause cell death and keratinization. Thus, ghost cells are indicative of cell death from local anoxia. This pathogenesis was later ruled out because of the occasional presence of ghost cells in vicinity of blood vessels.[10] Though Levy, et al. along with other authors believed that ghost cells are metaplastically transformed epithelial cells.[1,9] Many other concepts were put forth in due time.

The nature of ghost cells was described by various authors by similar and confusing terminologies like; a form of true keratinization,[11] prekeratin,[10] stages in the process of ortho-, para- and aberrant keratin formation,[1] abnormal/aberrant keratinization,[6,7,8] highly keratinized epithelial cells[12] and cells which have lost their developmental and inductive effect.[10] Chaves[12] (1968) contended that these cells are probably a special form of degeneration with a marked aberrant keratinization.

Sam Pyo Hong,[3] et al. (1991) reviewed 92 cases of CCOT and suggested that ghost cells might be the result of coagulative necrosis occurring at the same time when CCOT undergoes liquefaction necrosis. It was so interpreted because of their negative reactivity with cytokeratin antibody in contrast to marked reaction of adjacent odontogenic epithelium suggesting altered keratin antigen. All odontogenic epithelium and odontogenic tumors contain CK-19 including CCOT lining but ghost cells were virtually devoid of CK19 staining suggesting antigenic alterations.[13,14] Further evidences, which reinforce the degenerating nature of ghost cells, come from immunohistochemical studies done by Sissy and Rashad[15] (1999) which shows positive expression of CK13 in CP and CCOT but weak in ghost cells. Moreover, ghost cells do not express reactivity for cytokeratins[1,3,5,7] but express for AE1/AE3 and 34bE12.[14] This emphasizes their antigenic alteration which is probably due to coagulative necrosis of the odontogenic epithelium in CCOT.[14]

By staining epithelial cells differentiating into ghost cells, Yamamoto,[16] et al. (1988) found intense staining with high molecular weight keratins and reduced staining for involucrin than normal oral squamous epithelium. Thus, they concluded that these cells undergo an abnormal terminal differentiation by synthesizing altered homogenous acellular materials and ghost cells thus formed probably have different subclasses of keratins which has strong tendency to degenerate.

Mel-CAM protein has been related to focal adhesion, cytoskeletal organization, intercellular interactions, maintenance of the cell shape, and proliferation control and is expressed in suprabasal layer and in ghost cells but absent in basal cells suggesting its role in differentiation and thus hypothesizing ghost cells to be differentiating cells in CCOT.[14]

On the other hand, Gunhan,[17] et al. (1993) did not support the hypothesis of metaplastic transformation but believed their derivation is from cells that are programmed for “amelogenesis” in CCOT through cytoskeletal reorganization.

Lan[18] (2003) considered that the main mechanism leading to the development dead shadow cells, which seemed to have arisen from basaloid cells could be Apoptosis, because some transitional cells are seen between the basaloid cells and ghost cells and they were thus thought to represent apoptotic cells proceeding to ghost cells in Pilomatricoma. In an immunohistochemical review of odontogenic ghost cell carcinoma by Kim,[19] et al., a relation was observed between the ghost cells and apoptosis using apoptosis-related proteins such as Bcl-2, Bcl-XL which prevent apoptotic cell death and Bax which induces apoptosis. Ghost cells positivity for Bax and negativity for Bcl-2[14,19,20] suggested their formation to be an apoptotic process. In pilomatricomas bcl-2 expression was seen to be decreasing from basaloid to transitional cells and finally reaches zero in ghost cells. Thus, stressing upon the waning of bcl-2 during differentiation resulting in shadow cells.[21] Its negativity for cytokeratin and involucrin[16,19] helped authors propose that ghost cells might be a result of abnormal terminal differentiation toward keratinocytes or the process of apoptosis of the poorly differentiated odontogenic cells.[19]

Ghost cells stained positive, when Kusama,[22] et al. used hard α-keratin antibodies (hair protein) on Pilomatricoma, CCOT and CP. Thus, it appears that ghost cells might represent differentiation into hair in all these tumors of varying sites.

In 2007, when Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy was used for analyzing ghost cells in Dentigerous ghost cell tumors (DGCT), three different maturative stages of ghost cells were observed with varying extents of keratin expression, indicating accumulation of hard keratin in their cytoplasm during the pathological transformation process, thus indicating that ghost cells might represent differentiation into hair.[2]

Origin of ghost cells

Whether odontogenic or non-odontogenic pathology, ghost cells are always epithelial in origin without exceptions. Gorlin, et al.[6,7] Gold[23] and others[8] believed that these can originate from any layer of epithelium i.e., basal, intermediate or superficial. On the basis of differentiation of epithelium, it can arise from squamoid or stellate reticulum-like cells, as seen in CCOT. Ghost cells do not show intercellular junctions.[24]

Freedman, et al. observed only the central portion of the epithelial lining of CCOT transforming into ghost cells[25] whereas Ebling and Ephrain[26] observed ghost cells only at places of epithelium where basal membrane had disappeared. In a study by Pindborg[1] on odontomas; ghost cells were found within odontogenic epithelium/odontogenic rests, generally near or at the surface of the enamel matrix, entrapped within calcified tissue corresponding to either enamel or dentinal matrix and/or isolated within connective tissue.

Pattern of ghost cell degeneration, granulation tissue and calcifications associated with them

Abrams and Howell[8] speculated two unusual patterns of degeneration in CCOT leading to ghost cell formation. First pattern showed transformation of large mural squamous cells into eosinophilic cells retaining only the outline of original nucleus. Second pattern showed, individual or small groups of “stellate” and basal cells enlargement, displacement of their nuclei to the periphery and its disappearance thereafter, and such cells apparently account for the actual breaching of the epithelial membrane to place keratin in contact with connective tissue.

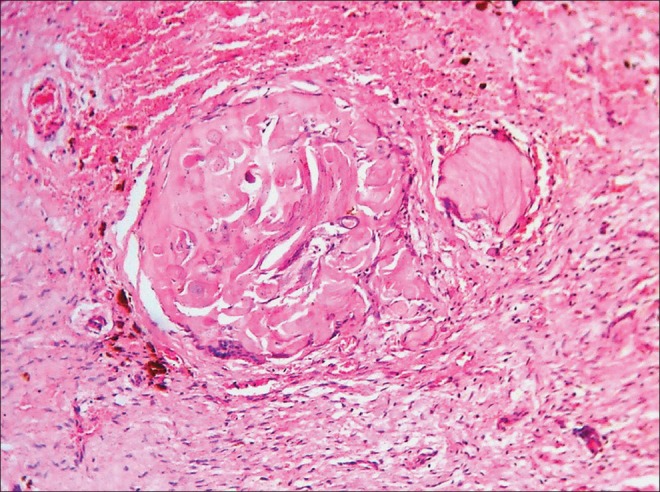

Ghost cells exhibit true herniation into connective tissue where these are considered as foreign bodies and induce granulation tissue response. According to a few earlier reports the granulation tissue so induced, initiates juxta-epithelial, homogenous, dentin-like areas and the ghost cells may be seen surrounded by the giant cells. Soon, the ghost cells become more homogenous and calcium salts appear [Figure 2].[6,7,8,27] Thus, dentinoid was once thought to be formed by granulation tissue. Although Smith and Blankenship had another view, according to which the convergence of ghost cells lead to the formation of dentinoid.[11] Gorlin,[6,7] et al. pointed towards an interesting appearance which resembled dentinoid under low magnification. This appearance was the product of occasional incorporation of viable epithelial cells in large masses of ghost cells and appeared to be dentinoid. Gorlin differentiated it from true dentinoid.

Figure 2.

Ghost cells undergoing calcifications.(Ref.: Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, MCODS, Mangalore, India)

Kerebel and Kerebel[10] suggested calcifying process in a ghost cell is passive one in which they become entrapped as calcification proceeds and with this embedding there is gradual degeneration until final dissolution. An ultra structural study conducted by Sapp and Gardner[28] on calcification of ghost cells in odontomas and CCOT revealed degenerating cytoplasm consisting of numerous, short bundles of tonofilaments. Calcifications in the form of concentric layers; Liesegang's rings, was seen occurring on the outer surface of such cells both on and between tonofilaments. Since degenerating foci is a prerequisite for dystrophic calcification, this finding also reinforces the degenerating nature of ghost cells. In a study done on undemineralized odontoma material, other than normally observed intracytoplasmic dysplastic calcifications; calcifications on an amyloid-like material which was probably produced by the ghost cells was also seen.[29]

At ultra structural level, ghost cells showed multiple round vesicles surrounded by unit membrane of about 70-100 Å in thickness and 800 and 3,000 Å in diameter containing radiopaque hydroxyapatite-like crystals. Such vesicles were seen losing their surrounding membranes depositing these crystals in areas of filamentous keratin was seen. These vesicles appeared to originate from subcellular organelles (lysosomes) or fragments of locally disintegrating keratinized epithelial cells in CCOT.[30] Murakami,[13] et al. by using cbfa-1 factor which is expressed in osteoblasts but not in ghost cells categorized the calcification related to ghost cells as dystrophic calcification. Similar granulation response and calcifications are seen in Pilomatricoma.[18]

Diagnosis

Ayub-Shklar stain showed distinct morphology and central clear area (indicating karyolysis) and a positive reaction of cells for keratin in Odontomas.[9]

To differentiate ghost cells from similarly stained cornified areas in CCOT, CP and Pilomatricoma, various stains were employed like Taenzer-Unna orcein, peracetic acid, azure A-eosin B, periodic acid-Schiff with or without diastase digestion, Bensley's modification of Mallory's stain, and the DDD stain for sulfhydril and disulfide of Barnett and Seligman. Although there were some differences in intensity and shade but areas with marked similarities were also present. Thus, both these appeared to be incomplete or aberrant keratinization. To differentiate ghost cells from true dentinoid phloxin-tartrazine stain can be used, it stains both but to a different degree.[6]

Ghost cells showed non-fluorescent to frankly positive yellow fluorescence when observed with the rhodamine B method, dull orange-brown to red with the Mallory's aniline blue reaction and light brown to bright yellow with van Gieson stain.[1] Ghost cells exhibit various degrees of chromophilia with Heidenhain's iron hematoxylin, negative staining with Alcian blue but some were PAS positive. Masson's trichrome stained dull brown, orange-brown, or red. Nuclei exhibited various stages of degeneration, from pyknosis to complete disappearance.[10]

Ghost cells are enamel matrix and/or keratin?

Ghost cells of odontogenic neoplasm and CP stain similar to enamel matrix with positive reaction for enamel protein markers. Thus, composition of ghost cells was perplexing. This similarity indicates towards the nature of ghost cells, which could be even pre-enamel or enameloid, which probably could not completely calcify to mature form because of the absence of odontoblasts and dentin.[25]

Although keratinization is not a normal event in odontogenic epithelium but amelogenesis is normal as stressed by Regezi,[31] et al., 1975 but there is an inherent potential of odontogenic epithelium to keratinize owing to its embryonic origin from oral ectoderm. Thus under certain circumstances odontogenic tumors and cysts and even CP owing to oral ectodermal origin can retain the potential to keratinize which is manifested in the form of ghost cells. Although Regezi, et al., found no evidence of granular layer between ghost cells and adjacent viable epithelial cells in 326 odontogenic tumors but electron micrographs revealed the presence of dense bundles of tonofilaments in the absence of keratohyaline granules. Thus, these cells probably represent an altered form of keratin but not true keratin.

Few authors suggested that these represent the product of abortive enamel matrix in odontogenic epithelium. Gunhan,[17] et al. suggested their derivation from cells programmed for “amelogenesis” in CCOT by using a set of markers. Ghost cells stain distinctly with enamelysin in CCOT and odontoma suggesting the presence of enamel protein.[31] Yoshida,[20] et al. demonstrated expression of amelogenin protein in the cytoplasm of ghost cells in CCOT. Takata, et al. concluded the presence of enamel-related protein (amelogenin, enamelin and sheathlin) and matrix-proteinase; enamelysin in the cytoplasm of ghost cells in the process of pathological transformation in CCOT but not in Pilomatricoma.[32,33] Thus it suggested that aberrant keratinization seems to make a minor contribution to the formation of ghost cells[33] since many immunohistochemical studies either have failed to demonstrate positive cytokeratin stain[16] or showed faint positivity[33] to positivity only in fragments.[17]

In point of fact, enamel matrix should be seen only near dentinoid but ghost cells are seen in the epithelium away from dentinoid tissue. This was demonstrated by Zussman[34] in 1966 by subcutaneous transplantation of enamel epithelium into homologous rats and showed that ameloblasts can secrete enamel matrix without the presence of dentin matrix or odontoblasts.

Prognosis

Keratinization in form of ghost cells is demonstrable in a wide range of odontogenic lesions but there is no difference regarding age/sex of patients and site of predilection from non-keratinizing odontogenic tumors nor do they exhibit different clinical behavior.[1,31] Apoptosis of tumor cells in form of ghost cells is probably responsible for the banal behavior of pilomatricoma.[18] The absence of ghost cells in Ameloblastomas could be attributed to different growth characteristics of these lesions. In ameloblastoma the epithelium proliferates in an unstrained fashion and forms a lytic, invasive tumor. Thus, the epithelium tends to remain viable, becoming more voluminous as the tumor grows. Whereas the epithelium of CCOT and most CP have reduced proliferative and infiltrative capacity along with a marked tendency to undergo senescent changes characterized by the formation of ghost keratin.[27]

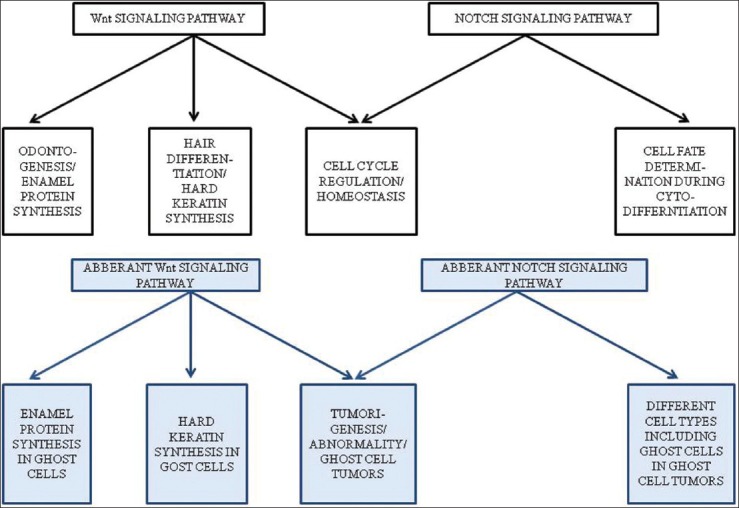

Role of Wnt (Wingless/Int-1) and notch signaling pathway in ghost cell fate and formation

The tumors which show characteristic presence of ghost cells have something in common other than ghost cells i.e., their probable molecular mechanism of pathogenesis. Studies suggest in some of these pathologies, a part of pathogenesis could be played by Wnt and Notch signaling pathways. Together, these two pathways act in a closely intertwined manner while maintaining tissue homeostasis, controlling cell fate, patterning and morphogenesis during embryonic development.[35,36,37] Extensive literature on the individual role of Wnt[35,36] and Notch[38,39] in carcinogenesis is available though relatively lesser on the ghost cell forming pathologies.

Wnt pathway sends signals through a family of cell-surface receptors called frizzled receptors (FRZ) and stimulates several pathways, the central one involving β-catenin and adenomatous polyposis coli gene (APC). There are possibilities that in presence of some aberrant signals mutated β catenin or inactivation of the APC gene, there is increase in the cellular levels of β-catenin, which in turn, translocates to the nucleus creating a cascade of events.[35,38,39,40] Accumulation of activated and mutated β-catenin in CCOTs, Pilomatricomas and CPs have been studied by Hassanein,[41] et al. who underlined a similar pathogenetic mechanism of tumorigenesis depicted by the unique pattern of keratinization and ghost cell formation in these neoplasms. He attributed this to the remarkable embryological similarity of tooth formation, hair formation, and formation of the adenohypophysis displaying an interplay between epithelium and neural/connective tissue which in turn is represented by these pathologies derived from the respective structures i.e., CCOT, pilomatricoma and CP. In yet another study by Sekine,[42] aberrant Wnt pathways were held responsible for the expression of similar enamel proteins in the ghost cells of CP and CCOT and emphasized on the common embryological origin form stomatodeal ectoderm and common genetic alterations between the two.

Wnt pathway has well established roles in organogenesis which includes hair and tooth formation including enamel protein formation.[41,42,43,44]

Another functionally similar but less complex pathway is Notch pathway. It consists of four receptors proteins (Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, and Notch4) and five membrane-bound ligand proteins (delta1, delta2, delta4, Jagged1 and Jagged2).[37] Through various modes of signaling, Notch enables adjacent cells to amplify and consolidate molecular differences and thus, adopt different fates and perform different functions within the same tissue in a spatially and temporally regulated manner.[37,38,39]

Siar,[45] et al. suggested Notch's oncogenic role in the tumorigenesis of CCOT and in enabling the adjacent cells to adopt different fates. He believed lateral positive induction occurred between adjacent ghost cells leading to activation of Notch1 by its cognate Jagged1 ligand which in turn exerted lateral inhibitory effect on the neighboring tumoral epithelium blocking them from adopting the same cell fate. Mineralized ghost cells also stained positive for Notch1 and Jagged1 and implicated that the calcification process might be associated with up regulation of these molecules. Nakano,[46] et al. also demonstrated Notch signalling activation in the CCOT cells and believed in their role in daughter cell fate regulation.

The aforesaid studies hypothesize how ghost cells determine their fate and their formation which could be the result of keratinization similar to the keratogenous zone of hairs where matrical cells lose their nuclei and keratinize into hair shafts and others speculate it to be abortive enamel formation or “dead end” in the road to calcified enamel formation. Apparently, Wnt and Notch (to some extent) plays role in the histogenesis of these neoplasms and also in the development of aberrant type of cells which appear to be similar in these neoplasms of odontogenic and non-odontogenic origin [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

The given diagram explains the various roles played by normal and aberrant Wnt and Notch signaling pathways with respect to ghost cell tumors.(Ref.: Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, MCODS, Mangalore, India)

CONCLUSION

The transformation of epithelial cells into more resistant terminally differentiated apoptotic cells i.e., ghost cells are responsible for the banal behavior of neoplasms and they also help in relieving the stress of the forming neoplasm.

The most accepted nature of ghost cells is aberrant keratinization that is altered form of keratin as it doesn’t stain with normal cytokeratin antibodies. Tonofilaments have been observed universally in the ghost cells of all the odontogenic or non-odontogenic tumors but these solely don’t satisfy their nature which is also found to be positive for enamel proteins in odontogenic tumors.

Although, studies prove an intricate functional relationship exists between Wnt and Notch signalling during development of neoplasms and in assigning cells to particular fates. Their relationship along with other signalling pathways complex interaction during tumorigenesis also needs intensive evaluation and this would help revealing the missing link between odontogenic and non-odontogenic tumors exhibiting these similar looking mysterious ghost cells.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Sedano HO, Pindborg JJ. Ghost cell epithelium in odontomas. J Oral Pathol. 1975;4:27–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1975.tb01737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucchese A, Scivetti M, Pilolli GP, Favia G. Analysis of ghost cells in calcifying cystic odontogenic tumors by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:391–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong SP, Ellis GL, Hartman KS. Calcifying odontogenic cyst. A review of ninety-two cases with reevaluation of their nature as cysts or a neoplasms, the nature of ghost cells, and sub classification. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;72:56–64. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90190-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Highman B, Ogden GE. Calcified epithelioma. Arch Pathol. 1944;37:169–74. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto K, Nelson RG, Lever WF. Calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe. Histochemical and electron microscopic studies. J Invest Dermatol. 1966;46:391–408. doi: 10.1038/jid.1966.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorlin RJ, Pindborg JJ, Clausen FP, Odont, Vickers RA. The calcifying odontogenic cyst: A possible analogue of the cutaneous calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe. An analysis of fifteen cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1962;15:1235–43. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(62)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorlin RJ, Pindborg JJ, Redman RS, Williamson JJ, Hansen LS. The calcifying odontogenic cyst. A new entity and possible analogue of the cutaneous calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe. Cancer. 1964;17:723–29. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196406)17:6<723::aid-cncr2820170606>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrams AM, Howell FV. The calcifying odontogenic cyst. Report of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:594–606. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy BA. Ghost cells and odontomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;36:851–5. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(73)90337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerebel B, Kerebel LM. Ghost cells in complex odontoma: A light microscopic and SEM study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;59:371–8. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith JF, Blankenship J. The calcifying odontogenic cyst. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:624–31. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaves E, Pessôa J. The calcifying odontogenic cyst. Report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:849–55. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami S, Koike Y, Matsuzaka K, Ohata H, Uchiyama T, Inoue T. A case of calcifying odontogenic cyst with numerous calcifications: Immunohistochemical analysis. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2003;44:61–6. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.44.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fregnani ER, Pires FR, Quezada RD, Shih leM, Vargas PA, de Almeida OP. Calcifying odontogenic cyst: Clinicopathological features and immunohistochemical profile of 10 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32:163–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Sissy NA, Rashad NA. CK13 in craniopharyngioma versus related odontogenic neoplasms and human enamel organ. East Mediterr Health J. 1999;5:490–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto Y, Hiranuma Y, Eba M, Okitsu M, Utsumi N, Tajima Y, et al. Calcifying odontogenic cyst immunohistchemical detection of keratin and involucrin in cyst wall. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1988;412:189–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00737142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunhan O, Celasun B, Can C, Finci R. The nature of ghost cells in calcifying odontogenic cyst: An immunohistochemical study. Ann Dent. 1993;52:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lan MY, Lan MC, Ho CY, Li WY, Lin CZ. Pilomatricoma of head and neck: A reterospective review of 179 cases. Arch Otolayrngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:1327–30. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.12.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Lee EH, Yook JI, Han JY, Yoon JH, Ellis GL. Odontogenic ghost cell carcinoma: A case report with reference to the relation between apoptosis and ghost cells. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:630–5. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.109016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshida M, Kumamoto H, Ooya K, Mayanagi H. Histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of calcifying odontogenic cysts. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:582–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.301002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farrier S, Morgan M. Bcl-2 expression in pilomatricoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:254–7. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusama K, Katayama Y, Oba K, Ishige T, Kebusa Y, Okazawa J, et al. Expression of hard alpha-keratins in pilomatrixoma, craniopharyngioma, and calcifying odontogenic cyst. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:376–81. doi: 10.1309/WVTR-R1DX-YMC8-PBMK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold L. The Keratinizing and calcifying odontogenic cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1963;16:1414–24. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(63)90375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbosa AA, Jr, Guimarães NS, Sadigursky M, Dantas R, Jr, Tavares I, Brandão M. Pilomatrix carcinoma (malignant pilomatricoma): A case report and review of the literature. An Bras Dermatol. 2000;75:581–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedmen PD, Lumerman H, Gee JK. Calcifying odontogenic cyst. A review and analysis of seventy cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;40:93–106. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebling H, Wagner JE. Calcifying odontogenic cyst. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1967;24:537–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(67)90434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein ML, Buchino JJ. The histologic similarity between craniopharyngioma and odontogenic lesion: A reappraisal. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;56:502–11. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sapp JP, Gardner DG. An ultra structural study of the calcifications in calcifying odontogenic cysts and odontomas. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;44:754–66. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piattelli A, Trisi P. Morphodifferentiation and histodifferentiation of the dental hard tissues in compound odontoma: A study of undemineralized material. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:340–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vuletin JC, Solomon MP, Pertschuk LP. Peripheral odontogenic tumor with ghost cell keratinization. A histologic, fluorescent microscopic and ultrastructural study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;45:406–15. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regezi JA, Courtney RM, Kerr DA. Keratinization in odontogenic tumors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;39:447–55. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takata T, Zhao M, Uchida T, Wang T, Aoki T, Bartlett JD, et al. Immunohistochemical detection and distribution of enamelysin (MMP-20) in human odontogenic tumors. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1608–13. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790081401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takata T, Zhao M, Nikai H, Uchida T, Wang T. Ghost cells in calcifying odontogenic cyst express enamel-related proteins. Histochem J. 2000;32:223–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1004051017425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zussman WV. Transplantation of enamel-forming epithelium. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;21:217–24. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Espada J, Calvo MB, Diaz-Prado S, Medina V. Wnt signaling and cancer stem cells. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:411–27. doi: 10.1007/s12094-009-0380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signaling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;434:843–50. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayward P, Kalmar T, Arias AM. Wnt/Notch signaling and information processing during development. Development. 2008;135:411–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allenspach EJ, Maillard I, Aster JC, Pear WS. Notch Signalling in Cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:466–76. doi: 10.4161/cbt.1.5.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radtke F, Raj K. The role of notch in tumorigenesis: Oncogene or Tumor suppressor? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:756–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim SA, Ahn SG, Kim SG, Park JC, Lee SH, Kim J, et al. Investigation of the beta-catenin gene in a case of dentinogenic ghost cell tumor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hassanein AM, Glanz SM, Kessler HP, Eskin TA, Liu C. Beta – catenin is expressed aberrantly in tumors expressing shadow cells. Pilomatricoma, craniopharyngioma, and calcifying odontogenic cyst. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:732–6. doi: 10.1309/EALE-G7LD-6W71-67PX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sekine S, Takata T, Shibata T, Mori M, Morishita Y, Noguchi M, et al. Expression of enamel proteins and LEF1 in adamantinomatous craniophayngioma: Evidence for its odontogenic epithelial differentiation. Histopathology. 2004;45:573–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka A, Okamoto M, Yoshizawa D, Ito S, Alva PG, Ide F, et al. Presence of ghost cells and the Wnt signaling pathway in odontomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:400–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kratochwil K, Dull M, Farinas I, Galceran J, Grosschedl R. Lef1 expression is activated by BMP-4 and regulates inductive tissue interactions in tooth and hair development. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1382–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siar CH, Kawakami T, Buery RR, Nakano K, Tomida M, Tsujigiwa H, et al. Notch signaling and ghost cell fate in the calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor. Eur J Med Res. 2011;16:501–6. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-16-11-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakano K, Siar CH, Tsujigiwa H, Nagatsuka H, Ng KH, Kawakami T. Immunohistochemical observation of Notch signalling in a case of calcifying cystic odontogenic tumor. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2010;19:147–52. [Google Scholar]