Abstract

Background:

Hypodontia or congenitally missing teeth is among dental anomalies with different prevalence in each region. The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of congenitally missing permanent teeth in Iranian population.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive, retrospective and cross-sectional study was done. Panoramic radiographs of 2422 Iranian patients (1539 girls and 883 boys), 7-25 years old, were collected. The radiographs were studied for evidence of congenitally missing teeth. Data were analyzed using Paired t-test, Mann-Whitney test, Fisher exact test and Chi-square test (α = 0.05).

Results:

Prevalence of congenitally missing teeth was totally 45.7% and 34.8% for third molars. The most frequent congenitally missing teeth was mandibular second premolars (23.34%) followed by maxillary second premolars (22.02%). Upper jaw showed significantly higher number of congenitally missing teeth (P value < 0.001). According to Chi-square test, congenital missing teeth was found approximately 10.9% in both females and males and there were no statistically significant difference between sexes (P = 0.19).

Conclusion:

The prevalence of congenitally missing teeth (CMT) in Iranian permanent dentition was 10.9%. The most common congenitally missing teeth were mandibular second premolar fallowed by maxillary second premolars.

Keywords: Congenital missing teeth, hypodontia, panoramic, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

The most common developmental and congenital dental anomaly is tooth agenesis. Congenitally missing teeth (CMT) refers to teeth whose germ did not develop sufficiently to allow the differentiation of the dental tissues.[1] It is defined as missing of one or more teeth.[2] It can be seen sporadic or in hereditary syndromes.

This anomaly occurs in three categories:

Hypodontia (Agenesis of less than 6 teeth, occurred without syndrome).[3,4,5,6]

Anodontia: (absence of all of the teeth, usually seen with ectodermal dysplasia).[9]

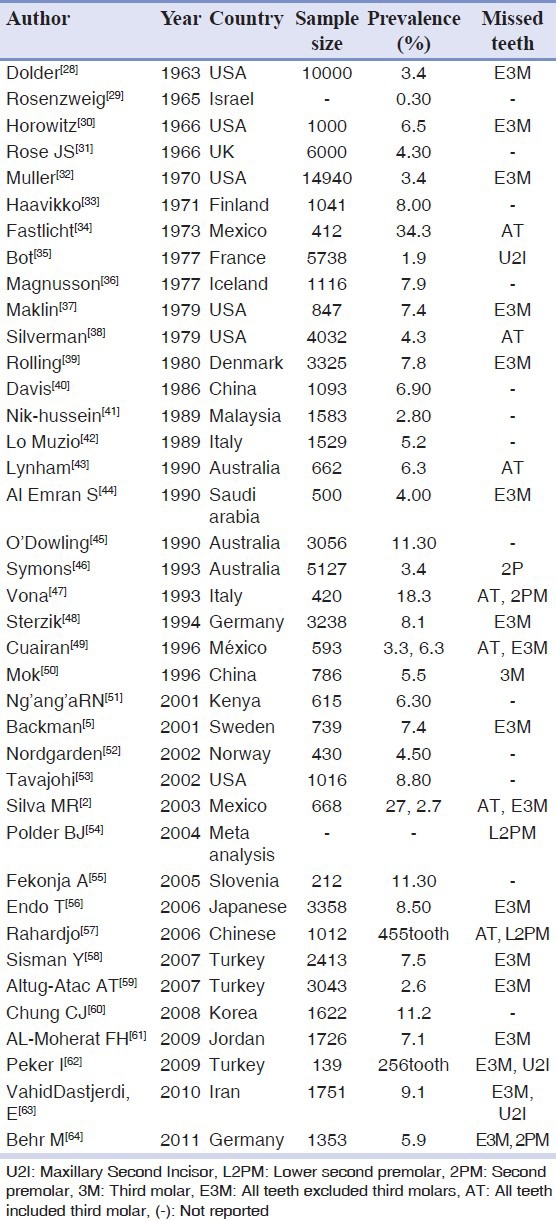

Etiology of tooth agenesis is not clear but some probable factors are: Heredity (mutations of the genes PAX9 and MSX1),[6,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] Ectodermal dysplasia, localized inflammation, trauma, radiation, and systemic conditions such as rickets, syphilis, etc.[1,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] CMT causes problems in chewing, speech and aesthetics.[5] Knowledge of the condition may help to develop more effective treatments.[2] In previous investigations, the prevalence of CMT varies in different populations from 0.3% to 34.3% [Table 1].[2,5,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64] (by considering and completion information from Table 1 of studies of Silva MR and Sisman Y, et al.[2,58]). Moyers, et al.[1] and Uner, et al.[65] reported prevalence of CMT 4%. It was reported 10% by Mc Donald.[9] The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of CMT in Iranian people's permanent dentition.

Table 1.

Prevalence of congenitally missing teeth in different population

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this retrospective study, quota sampling was used. A total of 3000 panoramic radiographs of patients referring faculties of dentistry or dental clinics in 8 provinces in Iran were reviewed. (Mazandaran, Khorasan razavi, Kerman, Esfahan, Azarbayejan Sharghi, Khozestan, Lorestan, Gilan). According to exclusion and inclusion criteria 2422 panoramic radiographs (36.5% males, 63.5% females) were selected. The patients were 7-35 years old. Inclusion criteria were: Having no specific syndrome Ectodermal dysplasia, Down, no lip/palate cleft, age more than 7 years old. Exclusion criteria were: History of tooth extraction or tooth loss due to trauma, caries, periodontal disease or orthodontic extraction, not enough radiographic quality to accurately diagnose the CMT. A tooth was considered congenitally missing when the absence of crown mineralization was confirmed in the panoramic radiographs. Data were collected and entered into the SPSS software (version 14.0 for Windows XP) then analyzed using Paired t-test, Mann-Whitney test, independent t-test, Chi-square test and Fisher exact test. (α = 0.05).

RESULTS

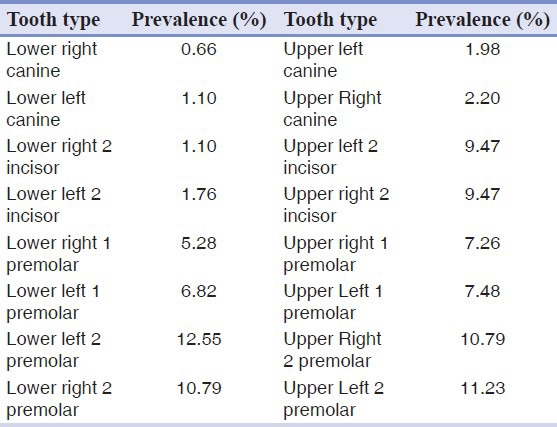

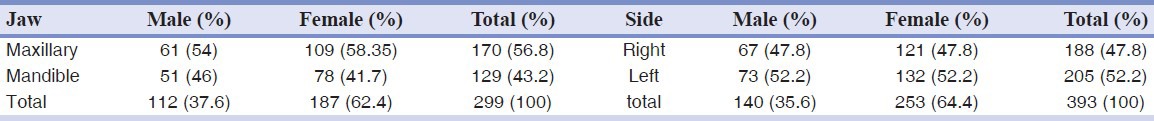

The patients were 7 to 53 years old (Mean: 9.3 ± 12.5). Prevalence of CMT including third molars was 45.7% and without it was 10.9%. In this paper, CMT was reported excluding third molars. According to Mann-Whitney test, there was no significant difference in the prevalence between males (10.9%) and females (10.8%). (P = 0.97) A total of 454 teeth, (males = 286, females = 168) in 262 patients were congenitally missing, with an average of 0.19 ± 0.6 teeth per patient (female = 0.185, male =0.19). The most common congenitally missing teeth were mandibular second premolars 23.34%, maxillary second premolars 22.02%, maxillary lateral incisors 18.94% and maxillary first premolars 14.74%, respectively [Table 2]. Chi-square test and Fisher exact test revealed that there were no significant differences between genders in terms of CMT distribution (P = 0.94). In this study, bilateral missing tooth in maxilla (63.5%) was more than mandible (36.5%) [Table 3]. Prevalence of CMT in mandible (43.2%) was less than maxilla (56.8%) [Table 4]. According to Paired-t-test, mean number of missing teeth in mandible, was significantly larger than maxilla (P = 0.001). The least common missing teeth were first and second molars of both jaws (with no missing case), followed by mandibular canine (1.76%).

Table 2.

Prevalence of congenitally missing teeth by tooth type excluding third molar (%)

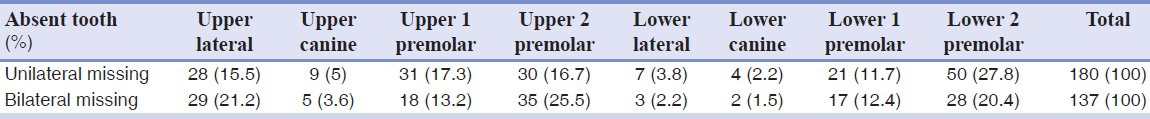

Table 3.

Distribution of unilateral and bilateral congenitally missing teeth in various types of teeth (%)

Table 4.

Distribution of congenital missing teeth by genders and jaws (%)

DISCUSSION

CMT is the most common developmental abnormality of teeth.[1] Several factors are proposed as etiology of CMT such as radiation, chemotherapy, some syndromes (such as Down syndrome, etc), infection and local inflammation, specific pattern of innervations, some systemic diseases, the changes resulting from human developmental and genetic factors, etc; however the main cause is still unknown.[1,2,5,54,59,60,61,62,64] Although CMT occurs in many syndromes, the incidence of non-syndromic and familial form is more.[62] Some studies believe that it has been happening more commonly in recent decades.[58] The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of CMT without focusing on a special patient group in Iran. There are differences between results of studies on CMT. The main reasons for these differences were:

Different methods and materials

Whether the study included third molar or not.

How many people were included in the study?

Was sampling performed randomly or from specific groups (such as orthodontic patients)?

What should the age range of patients be?

What are the excluding criteria?

What method was used to provide radiographs?

For example Moyers, et al.[1] declared that the age more than 4.5 to 5 years is appropriate, while Sisman believes that calcification begins in the age of 3 and finishes at 6 years.[58] Michael Behr, et al. believed that after age of 7 differences in results are negligible.[64] Endo, et al.[56] reported that calcification of premolars could be delayed until ages 9-12 years and others stated that before age of 10 we can calculate prevalence of CMT, accurately.[5,56,61] Wisth, et al.[66] found that prevalence of CMT in 7-year-olds was 0.5% more than 9-year-olds. While Polder, et al.[54] in a meta-analysis study found that there was no significant difference in prevalence of CMT between ages below and above 7 years. Such differences can probably lead to various reports.

Genetics

The role of heredity in the incidence of CMT has been identified and even several involved genes have been introduced.[20] Behr, et al.,[64] studied on two different races in South of Germany and found that not only was CMT observed more in some races, but also type of prevalent missing teeth could be different among them.

Social and environmental factors

In low socioeconomic communities, oral health may be poor and consequently higher caries and dental infections occur.[67] According to a number of findings that declare local infection and inflammation to be etiologic factors for CMT,[1] the incidence of CMT caused by these factors will be higher.

The purpose and motivation of researchers

Sampling among specific patients such as orthodontic treatment candidates may be the reason for different reports of CMT.[1,58,60,61,63,64] The importance of this reason is so much that Polder, et al.[54] in their meta-analysis study, excluded studies including only orthodontic patients. Al-Moherat, et al.[61] expressed that missing anterior teeth or lack of more than one tooth in a quadrant causes application for orthodontic treatment more often, so that more missing anterior teeth would be reported. However, selection of orthodontic patients for CMT assessment is for easier access and sufficient number of their records like panoramic radiographs and some studies discussed that this approach neither causes overestimation of CMT,[2,60] nor differs in missing patterns.[54,58] i.e., Sisman, et al.[58] reported the prevalence of CMT in orthodontic patients is the same as general population.

In an effort to reduce errors in the present study, the target population was not limited to orthodontic patients. Eight different ethnic and social areas of Iran were included in this study. Therefore environmental, ethnic and social factors were distributed proportionally. Minimum included age was seven. Therefore, because of third molar tooth bud formation, we can make sure that the accuracy of prevalence assessment was acceptable.[1,54,58,64]

Prevalence of congenitally missing teeth

In our study, prevalence of CMT including the third molars is 45.7% and without them is 10.9%. This value is higher than most of previous studies [Table 1] and similar to Chung's report in Korea (11.2%) and finding of Fekonja in Slovenia (11.3%).[55,60] Prevalence of CMT in our research is lower than Michael Behr's study in Germany (12.6%).[64] Altogether, prevalence of Iranian's CMT, is higher than many communities. This fact is in accordance with the results of Vahid-Dastjerdi, et al.[63] in Iran i.e. in Polder, et al.’s meta-analysis study (2004) the average prevalence of CMT, according to data obtained from Australian (6.3%), North America (3.5%) and Europe (5.5%), are much lower than Iran's community and this can be due to racial differences and different oral hygiene in Iran's society.

Males and females

In the present study, prevalence of CMT is 10.9% in males and 10.8% in females. Although in many studies, the average prevalence of CMT in females are more than males,[5,54,55,56,58,61,62] Silva, et al.[2] in Mexico, Chung, et al.[60] in Korea and Behr, et al.[64] in Germany concluded that CMT in females and males are almost equal. In all of these studies differences of genders were not significant.[5,55,56,58,61,62,64] Only Polder, et al.[54] concluded that CMT in females are 1.3 times more probable than males with significant differences. We suggest the fact that women are more anxious than men about dental visits, leads to higher prevalence of CMT for them.

Maxilla and mandible

In our study, 56.8% of CMT were in maxilla and 43.2% in mandible, therefore prevalence in maxilla is more than mandible significantly. Our findings were similar to the results of many previous studies.[2,55,58,60,61,62,63,64] While Backman, et al.[5] in Sweden reported the prevalence of CMT in mandible more than maxilla. Polder, et al.,[54] reported that the prevalence of CMT in both jaws is almost equal. Pattern of tooth innervations may be one of the risk factors of CMT in the maxilla.[68] Perhaps different type of innervations can justify more frequent CMT in this jaw. However, further studies should be conducted.

Common missed teeth

In this study, the most frequent missing tooth was mandibular second premolars (23.34%), maxillary second premolar (22.02%), maxillary lateral incisors (18.94%), and maxillary first premolars (14.74%). Prevalence of other teeth is illustrated in [Table 2]. After third molars as the most prevalent missing teeth in all of the studies, there are some differences between the prevalence of other teeth. In contrast with our finding, in most of the studies which evaluated orthodontic patients, the most common CMT was maxillary lateral incisors, followed by mandibular and maxillary second premolars.[2,55,58,59,61,62,63] The cause of these differences refers to different sampling which is not limited to orthodontic patients in the present study, however the results of Behr, et al.[64] in Germany (2011) is accurately similar to our findings. Interestingly, results of studies with general population are different. As Polder, et al.,[54] reported in Europe, North America and Australia, the most common congenitally missed teeth are mandibular second premolars followed by maxillary first premolars and maxillary second premolars.[54] The results of this study in first prevalent CMT are consistent with results of our study. Ethnic differences in our population may be cause of disparity in second prevalent teeth. Also, Endo, et al.[56] in Japan and Rahardjo, et al.[57] in China in their studies on orthodontic patients concluded that most frequent CMT after third molars are: Mandibular second premolars, maxillary lateral incisors and mandibular lateral incisors, respectively. Also, Chang, et al.[60] in South Korea declared that the most frequent CMT is mandibular lateral incisors, followed by the mandibular second premolars and maxillary second premolars. Probably racial differences in mongoloid race in East of Asia, is the most important factor that which made mandibular lateral incisors the most common CMT in Korea, Japan and China. It is clear that our results are more similar to studies whose population is not limited to orthodontic patients. Although not extensible, it can probably demonstrate the role of tooth region in prevalence of CMT in orthodontic patients.

Least prevalent missing teeth

Our findings reveal that the least prevalence of CMT belongs to first and second molars of both jaws (0.0%), followed by mandibular canine (1.76%) [Table 2]. Our results agree with studies conducted by Chung, et al.[60] in Korea, Endo, et al.[56] in Japanese, Peker, et al.[62] in Turkey and Fekonja, et al.[55] in Slovenia. Albeit in Sisman, et al’s study, in Turkey and Backman, et al’s study in Sweden the least prevalence was pertaining to upper and lower canines.[5,58]

Unilateral and bilateral

In all of the assessed radiographs, number of individuals with unilateral CMT is more than those with bilateral CMT, but this difference is not significant [Table 3]. While in all of the assessed radiographs, total number of bilateral CMT are more than unilateral. In study of Chung, et al.,[60] in South Korea and Polder, et al.,[54] in Europe, Australia and North America revealed same results and unilateral CMT was significantly more than bilateral. In the present study, bilateral CMT in maxilla (63.5%) is significantly higher than mandible (36.5%) [Table 4]. This is due to the relatively high frequency of bilateral CMT in maxillary lateral incisors. Like our finding, Polder, et al.,[31] stated in their meta-analysis study that bilateral missing of maxillary lateral incisors is much more than unilateral and for other teeth unilateral CMT is more frequent. Our findings are in contrast with findings of Silva, et al.[2] in Mexico and Endo, et al.[56] in Japan, probably due to racial differences of assessed communities.

Number of congenitally missing teeth in each person

The most common form of CMT is single tooth missing (47%), and then double teeth (40%) and the lowest prevalence belongs to missing of five teeth (0.35%) and six teeth (0.35%). Therefore, present study supports other studies; however the percentages are quite different.[54,56,58,60] In the present study, the prevalence of oligodontia according to Shalk Van's definition (missing 6 teeth or more) is 0.35%.[69] This finding is similar to that of Vahid-Dastjerdi, et al.’s study on orthodontic patients in Iran.[63] There is no anodontia in this study. Prevalence of oligodontia in this study is less than results of Polder and et al.[54] in Europe, North America and Australia (2.6%), Chung, et al.[60] in Korea (5.1%), Endo, et al.[56] in Japan (10.1%). Racial differences among various communities may justify these differences. Average number of CMT is 0.19 ± 0.6 teeth per person in our study.

Right and left sides

In this study, 47.8% of CMT are in the right and 52.2% are in the left side of jaws, but the difference was not significant [Table 4]. Our results agree with result of Sisman, et al.[58] in Turkey and in contrast with the findings of Fekonja, et al.[55] in Slovenia. while Silva, et al.[2] in Mexico, Endo, et al.[56] in Japan and Al-Mehrat, et al.[61] in Jordan concluded that the incidence of CMT is equal in both sides. Of course they did not find any significant relationship in this regard. Our findings are more similar to studies limited to specific groups, such as orthodontic patients.[54,59,60]

We suggest selecting equal number of males and females for more accurate evaluation of sex ratio. Considering the high prevalence of CMT of mandibular second premolars and maxillary second premolar and lateral incisors, we recommend taking diagnostic radiographs in eruption tooth ages to evaluate the presence or missing of them, and predict probable use of space retainer and other supportive therapies to reduce the esthetic and functional consequences of CMT, as Hakan Tuna, et al.[70] emphasized in their clinical report. Limitation of the present study is unavailability of the whole society. Due to ethical considerations, one cannot prescribe panoramic radiographies for the patients randomly. Therefore, we had to select the cases from subjects referring our dental clinics and faculties. We suggest designing studies to assess familial history aspects of CMT in retrospective or prospective approach to provide better estimation and evaluation of role of genetic in CMT.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of CMT in Iran is more in comparison with many population groups, therefore the importance of diagnosis and management of these teeth is most important. By early detection of missing teeth, alternative treatment modalities can be planned and minimize the complications of CMT. The most frequent missing teeth was mandibular second premolar fallowed by maxillary second premolar and maxillary lateral incisor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to express our sincere acknowledgement in the support and help of Torabinejad Research Center and dental faculty of Isfahan University of Medical Science.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was financially supported and approved by Isfahan University of Medical Science

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Moyers RE, Riolo ML. Early treatment. In: Moyers RE, editor. Handbook of orthodontics. 4th ed. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1988. pp. S348–S53. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silva MR. Radiographic assessment of congenitally missing teeth in orthodontic patients. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:112–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salama FS, Abdel-Megid FY. Hypodontia of primary and permanent teeth in a sample of Saudi children. Egypt Dent J. 1994;40:625–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vastardis H. The genetics of human tooth agenesis: New discoveries for understanding dental anomalies. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;117:650–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Backman B, Wahlin YB. Variations in number and morphology of permanent teeth in 7 year old Swedish children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11:11–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2001.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arte S, Nieminen P, Pirinen S. Gene defect in hypodontia: Exclusion of EGF, EGFR, and FGF-3 as candidate genes. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1346–52. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750060401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schalk-van der WY, Steen WH, Bosman F. Distribution of missing teeth and tooth morphology in patients with oligodontia. ASDC J Dent Child. 1992;59:133–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stockton DW, Das P, Goldenberg M. Mutation of PAX9 is associated with oligodontia. Nat Genet. 2000;24:18–9. doi: 10.1038/71634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ralph E, McDonald RE, Avery DR. Developmental and morphology of primary teeth. In: Dolan J, editor. Dentistry for the child and Adolescent. 9th ed. philadelphia: Mosby; 2011. pp. 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das P, Stockton DW, Bauer C. Haploinsufficiency of PAX9 is associated with autosomal dominant hypodontia. Hum Genet. 2002;110:371–6. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frazier-Bowers SA, Guo DC, Cavender A. A novel mutation in human PAX9 causes molar oligodontia. J Dent Res. 2002;81:129–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldenberg M, Das P, Messersmith M. Clinical, radiographic, and genetic evaluation of a novel form of autosomal-dominant oligodontia. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1469–75. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790070701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulrich K. Freckles and dysplasias of the eyebrows as indicators for genetic abnormalities of the development of the teeth and the jaws. Stomatol DDR. 1990;40:46–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stimson JM, Sivers JE, Hlava GL. Features of oligodontia in three generations. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1997;21:269–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman GV, Newman RA. Report of four familial cases with congenitally missing mandibular incisors. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;114:195–207. doi: 10.1053/od.1998.v114.a87015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lapter M, Slaj M, Skrinjaric I, Muretic Z. Inheritance of hypodontia in twins. Coll Antropol. 1998;22:291–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmeister H. Microsymptoms as an indication for familial hypodontia, hyperdontia and tooth displacement. Dtsch Zahnarztl Z. 1977;32:551–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burzynski NJ, Escobar VH. Classification and genetics of numeric anomalies of dentition. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1983;19:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Coster PJ, Marks LA, Martens LC, Huysseune A. Dental agenesis: Genetic and clinical perspectives. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mostowska A, Kobielak A, Trzeciak WH. Molecular basis of non-syndromic tooth agenesis: Mutations of MSX1 and PAX9 reflect their role in patterning human dentition. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:365–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kindelan JD, Rysiecki G, Childs WP. Hypodontia: Genotype or environment? A case report of monozygotic twins. Br J Orthod. 1998;25:175–8. doi: 10.1093/ortho/25.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenzweig KA, Garbarski D. Numerical aberrations in the permanent teeth of grade school children in Jerusalem. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1965;23:277–83. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330230315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horowitz JM. Aplasia and malocclusion: A survey and appraisal. Am J Orthod. 1966;52:440–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(66)90122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milazzo A, Alexander SA. Fusion, gemination, oligodontia, and taurodontism. J Pedod. 1982;6:194–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sperber GH. Anodontia-two cases of different etiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1963;16:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(63)90366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brook AH. A unifying aetiological explanation for anomalies of human tooth number and size. Arch Oral Biol. 1984;29:373–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(84)90163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werther R, Rothenberg F. Anodontia: A review of its etiology with presentation of a case. Am J Orthod Oral Surg. 1939;25:61–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolder E. Deficient dentition. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1936;57:142–3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenzweig KA, Garbarski D. Numerical aberrations in the permanent teeth of grade school children in Jerusalem. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1965;23:277–83. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330230315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horowitz JM. Aplasia and malocclusion: a survey and appraisal. Am J Orthod. 1966;52:440–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(66)90122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rose JS. A survey of congenitally missing teeth, excluding third molars, in 6000 orthodontic patients. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1966;17:107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller TP, Hill IN, Peterson AC, Blayney JR. A survey of congenitally missing permanent teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1970;81:101–7. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1970.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haavikko K. Hypodontia of permanent teeth. An orthopantomographic study. 1971;67:219–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fastlicht RJ. Vol. 11. Mexico: Revista de la Academia Nacional de Estomatologia; 1973. Agenesia de las piezas dentarias permanentes; pp. 17–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Bot P, Salmon D. Congenital defects of the upper lateral incisors (ULI): condition and measurements of the other teeth, measurements of the superior arch, head and face. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1977;46:231–43. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330460204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magnusson TE. An epidemiologic study of dental space anomalies in Icelandic schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1977;5:292–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1977.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maklin M, Dummett CO, Jr, Weinberg R. A study of oligodontia in a sample of New Orleans children. ASDC J Dent Child. 1979;46:478–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silverman NE, Ackerman JL. Oligodontia: a study of its prevalence and variation in 4032 children. ASDC J Dent Child. 1979;46:470–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rolling S. Hypodontia of permanent teeth in Danish schoolchildren. Scand J Dent Res. 1980;88:365–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1980.tb01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis PJ. Hypodontia and hyperdontia of permanent teeth in Hong Kong schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15:218–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nik-Hussein NN. Hypodontia in the permanent dentition: a study of its prevalence in Malaysian children. Aust Orthod J. 1989;11:93–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lo ML, Mignogna MD, Bucci P, Sorrentino F. [Statistical study of the incidence of agenesis in a sample of 1529 subjects] Minerva Stomatol. 1989;38:1045–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynham A. Panoramic radiographic survey of hypodontia in Australian Defense Force recruits. Aust Dent J. 1990;35:19–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1990.tb03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Emran S. Prevalence of hypodontia and developmental malformation of permanent teeth in Saudi Arabian schoolchildren. Br J Orthod. 1990;17:115–8. doi: 10.1179/bjo.17.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Dowling IB, McNamara TG. Congenital absence of permanent teeth among Irish school-children. J Irish Dent Assoc. 1990;36:136–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Symons AL, Stritzel F, Stamation J. Anomalies associated with hypodontia of the permanent lateral incisor and second premolar. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1993;17:109–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vona G, Piras V, Succa V, Distinto C. Dental agenesis in Sardinians. Anthropol Anz. 1993;51:333–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sterzik G, Steinbicker V, Karl N. [The etiology of hypodontia] Fortschr Kieferorthop. 1994;55:61–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02174358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cuairán RV, Gaitan ZL, Hernández MA. Agenesia dental en una muestra de pacientes ortodónticos del Hospital Infantil de México. Revista de la Asociación Dental Mexicana. 1996;53:211–5. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mok YY, Ho KK. Congenitally absent third molars in 12 to 16 year old Singaporean Chinese patients: a retrospective radiographic study. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:828–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ng’ang’a RN, Ng’ang’a PM. Hypodontia of permanent teeth in a Kenyan population. East Afr Med J. 2001;78:200–3. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i4.9063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nordgarden H, Jensen JL, Storhaug K. Reported prevalence of congenitally missing teeth in two Norwegian counties. Community Dent Health. 2002;19:258–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tavajohi-Kermani H, Kapur R, Sciote JJ. Tooth agenesis and craniofacial morphology in an orthodontic population. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2002;122:39–47. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.123948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polder BJ, van’t Hof MA, Van der Linden FP, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of dental agenesis of permanent teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:217–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fekonja A. Hypodontia in orthodontically treated children. Eur J Orthod. 2005;27:457–60. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cji027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Endo T, Ozoe R, Kubota M. A survey of hypodontia in Japanese orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahardjo P. Prevalence of hypodontia in Chinese orthodontic patients. Dent J (Maj.Ked.Gigi) 2006;39:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sisman Y, Uysal T, Gelgor IE. Hypodontia. Does the prevalence and distribution pattern differ in orthodontic patients? Eur J Dent. 2007;1:167–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altug-Atac AT, Erdem D. Prevalence and distribution of dental anomalies in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:510–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chung CJ, Han Jh, Kim KH. The pattern and prevalence of hypodontia in Koreans. Oral Dis. 2008;14:620–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Al-moherat FH, Al-ebrahim HM, Al-shurman IS. Hypodontia in orthodontic patients in Southern Jordan. Pak Oral Dent J. 2009;29:45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peker I, Kaya E, Drendeliler-Yaman S. Clinic and radiographical evaluation of non-syndromic hypodontia and hyperdontia in permanent dentition. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14:393–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vahid-Dastjerdi E, Borzabadi-Farahani A, Mahdian M, Amini N. Non-syndromic hypodontia in an Iranian orthodontic population. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:455–61. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Behr M, Proff P, Leitzmann M. Survey of congenitally missing teeth in orthodontic patients in Eastern Bavaria Behrstern. Eur J Orthod. 2011;33:32–6. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uner O, Yncel-Ero lu E, Karaca I. Delayed calcification and congenitally missing teeth: Case report. Aust Dent J. 1994;39:168–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1994.tb03087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wisth PJ, Thunold K, BöE OE. Frequency of hypodontia in relation to tooth size and dental arch width. Acta Odontol Scand. 1974;32:201–6. doi: 10.3109/00016357409002548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reisine ST, Psoter W. Socioeconomic status and selected behavioral determinants as risk factors for dental caries. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1009–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kjaer I, Kocsis G, Nodal M, Christensen LR. Aetiological aspects of mandibular tooth agenesis, focusing on the role of nerve, oral mucosa, and supporting tissues. Eur J Orthod. 1994;16:371–5. doi: 10.1093/ejo/16.5.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schalk-van der Weide Y. Utrecht: University of Utrecht; 1992. Oligodontia: a clinical, radiographic and genetic evaluation, dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hakan Tuna S, Keyf F, Pekkan G. The Single-tooth Implant Treatment of Congenitally Missing Maxillary Lateral Incisors Using Angled Abutments: A Clinical Report. Dent Res J. 2010;6:93–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]