Abstract

The individual contributions of each of the six conserved disulfide (SS) bonds in the dengue 2 virus envelope (E) glycoprotein (strain 16681) to epitope expression was determined by measuring the reactivities of a panel of well-defined monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) with LLC-MK2 cells that had been transiently transformed with plasmid vectors expressing E proteins that were mutant in their SS bonds. Three domain I (DI) epitopes (C1, C3, and C4) were affected by elimination of any SS bond and were essentially the only epitopes affected by elimination of the amino-proximal SS1 formed between Cys 3 and Cys 30. The remaining DI epitope (C2) was sensitive to only SS3-bond (Cys 74-Cys 105) and SS6-bond (Cys 302-Cys 333) elimination. Of the four DII epitopes examined, reactivities of three anti-epitope MAbs (A1, A2, and A5) were reduced by elimination of SS2 (Cys 61-Cys 121), SS3, SS4 (Cys 94-Cys 116), SS5 (Cys 185-Cys 285), or SS6. The other DII epitope examined (A3) was sensitive only to SS2- and SS3-bond elimination. The three DIII epitopes tested (B2, B3, and B4) were most sensitive to elimination of SS6. The flavivirus group epitope (A1) was less sensitive to elimination of SS3 and SS6. This result may indicate that the region proximal to the E-protein fusion motif (amino acids 98 to 110) may have important linear components. If this observation can be confirmed, peptide mimics from this region of E protein might be able to interfere with flavivirus replication.

The flavivirus envelope (E) glycoprotein encodes important phenotypic and immunogenic properties of the virion (7, 17). This protein elicits virus-neutralizing antibodies, mediates virus-cell membrane fusion, and initiates infection through binding to cell surfaces. The high-resolution crystal structures of the ectodomain of the tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) virus and dengue type 2 (DEN2) virus E-protein homodimers have been solved (13, 16). The three structural domains (DI, DII, and DIII) identified in the E protein were roughly analogous to the previously defined antigenic domains (C, A, and B) (Fig. 1). The amino acid sequence of the ectodomain of all flavivirus E proteins contains 12 strictly conserved cysteine residues that form six disulfide (SS) bonds (14). For DEN2 virus, the SS1 bond (Cys 3 bonded to Cys 30) stabilizes an amino-terminal loop (Fig. 1). The SS2 (Cys 60-Cys 121), SS3 (Cys 74-Cys 105), and SS4 (Cys 92-Cys 116) bonds stabilize the amino-proximal part of DII that harbors the virus membrane fusion sequence located at amino acids (aa) 98 to 110 (17, 19). SS5 (Cys 185-Cys 285) stabilizes the carboxy-proximal loop of DII, which is separated from the amino-proximal DII loop by DI. The SS6 bond makes the only bridge in DIII (Cys 302-Cys 333).

FIG. 1.

Location of SS bridges in the deduced crystal structure of the DEN2 virus E-protein dimer. Overhead (A) and lateral (B) view of the predicted three-dimensional backbone of the DEN2 16681 E protein. The mutated amino acid from each SS-bond pair is noted in space fill on one of the E-protein monomers and is defined in Table 1. Domains I (dark gray), II (white), and III (black) as defined by the DEN2 E-protein crystal structure (9) are shown.

Reduction of all six of the West Nile virus E-protein SS bonds resulted in a protein that was unable to elicit virus-neutralizing antibody in mice (23). To date, only DIII SS6 has been investigated individually for its contribution to the structure and function of the E protein. SS6 is of particular interest because of experimental evidence implicating DIII in cell attachment (5). By using proteolytic fragments of the TBE virus E protein, it was shown that SS6 spontaneously reformed following reduction and oxidation, suggesting that the surrounding secondary structure favored SS6 bond formation (25). This bond was also critical for the correct antigenic structure of the E proteins of DEN1 and DEN2 viruses (9, 12).

The antigenic structure of the DEN2 virus E protein has been investigated previously using monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (8, 17). Not unexpectedly, the DEN2 virus E-protein antigenic structure was similar to the TBE virus E-protein antigenic structure. Three antigenic regions (A, B, and C) with unique biochemical characteristics were identified, and these regions correlated well with their analogous regions in the TBE virus E protein. The locations of many of the epitopes were mapped on the DEN2 E-protein three-dimensional structure using MAb competition binding assays, binding of MAb to peptide fragments, and serological testing of MAbs (17).

In this study we used site-directed mutagenesis of a chimeric plasmid expressing the prM and E proteins of DEN2 virus strain 16681 to determine the individual contributions of the six SS bonds to E-protein epitope expression. This chimeric plasmid, pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1, expressed modified DEN2 proteins (4). The DEN2 prM signal sequence was replaced by the Japanese encephalitis virus prM signal sequence. The last 20% (aa 397 to 450) of the DEN2, E-protein ectodomain, was replaced with the same region from the Japanese encephalitis virus E protein. These modifications in the prM and E proteins enhanced secretion of recombinant subviral particles from COS-1 cells transiently transformed with the pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1 plasmid compared with that from COS-1 cells transiently transfected with a plasmid containing the complete wild-type DEN2 prM and E-protein genes (pCBD2-14-6). Recombinant subviral particles secreted from transformed COS-1 cells contained prM and E proteins and very small amounts of M protein. The E-protein epitopes (A1, A2, A5, C1, C3, C4, B2, B3, and B4) expressed by acetone-fixed, plasmid-transfected COS-1 cells and probed with a panel of well-defined MAbs were identical to those expressed in DEN2 virus-infected cells and cells transformed with plasmid containing prM and 100% DEN2 E protein (4). The specific information on the construction and characterization of these DEN2 virus-derived plasmids has been described in a separate paper (4).

Site-directed mutagenesis of one Cys in each of the six SS bonds of the E protein expressed by the pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1 plasmid was performed as described in the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The primers were designed using the recommendations from Stratagene and Lasergene (DNASTAR, Madison, Wis.), and the primers used and the introduced mutations are listed in Table 1. The mutated plasmids were electroporated into XL-1 Blue Escherichia coli cells and grown on Luria broth plates containing antibiotic at 37°C overnight. Individual isolated colonies were picked and grown in Luria broth media containing antibiotic at 37°C overnight. The DNA from cells was purified using QIAfilter Plasmid Maxi Prep kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.). The purified plasmids were sequenced across the mutation to verify that only the engineered mutations were present. Ten micrograms of plasmid was electroporated into 5 × 106 LLC-MK2 cells by using a gene pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) set to 2.5 kV, 950 μF, and infinite Ohms. The transformed cells were grown in 75-cm2 flats for 48 h, harvested to prepare spot slides, and used for end-point dilution epitope mapping by indirect fluorescent antibody tests as previously described (20). To determine the effects that SS-bond elimination had on the conformation and maturation of the E protein and the ability of the E protein to be transported to the cell surface, virus-transformed cells were tested either unfixed or following fixation for 15 min in ice-cold acetone.

TABLE 1.

Mutagenic oligonucleotide primers and location of the nucleotide and resultant amino acid mutational changes made in the DEN2 E-protein SS bridgesa

| Mutant (SS bond location) | Primer sequence | Nucleotide change (no.) | Amino acid change (no.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SS1 (3-30) | GAACATGGGAGCGCTGTGACGACG | TGT→GCT (1023) | C→A (30) |

| SS2 (60-121) | CACCCTAAGGAAGTACGCTATAGAGGCAAAG | TGT→GCT (1114) | C→A (60) |

| SS3 (74-105) | GGATGGGGAAATGGAGCTGGACTATTTGG | TGT→GCT (1249) | C→A (105) |

| SS4 (92-116) | GAGGCATTGTGACCGCTGCTATGTTCAG | TGT→GCT (1282) | C→A (116) |

| SS5 (185-285) | CAGGACATCTCAAGGCTAGGCTGAGAATG | TGC→GCT (1789) | C→A (285) |

| SS6 (302-333) | GACGGCTCTCCAGCTAAGATCCCTTTTG | TGC→GCT (1933) | C→A (333) |

The primer design was based upon the sequence of the pD2/IC-30P-A clone as recommended by Stratagene and Lasergene. The bold nucleotides are those which encode the amino acid changes from the wild type. Nucleotide and amino acid changes are listed in parentheses. Amino acid locations are numbered from the E-protein amino terminus; bold Cys residues were mutated.

Three patterns of E-protein-specific MAb reactivity were observed on the surfaces of either unfixed or acetone-fixed cells transformed with SS-bond mutants, and these patterns correlated well with previously defined epitope location and resistance to reduction of the DEN2 E-protein antigenic domains. Table 2 shows MAb reactivity with acetone-fixed cells. Three DI epitopes (C1, C3, and C4) were affected by elimination of any SS bond, including SS1. The remaining DI epitope (C2) was effected by abolition of only SS3 and SS6. Only the binding of anti-DI MAbs were consistently affected by SS1 elimination, correlating well with the DI location of SS1. The C1 epitope, which has been mapped to aa 121 to 157 in fragment binding experiments, has been shown previously to be linearly distal from, but spatially proximal to, SS1 (17).

TABLE 2.

Effect on MAb binding to expressed DEN2 16681 prM/E protein after elimination of individual SS bonds

| Epitope (MAb) | E domain | Fold change in MAb titer with SS bridge:a

|

Fold change in MAb titer with pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

|||

| 3-30b | 60-121 | 74-105 | 92-116 | 185-285 | 302-333 | |||

| A1 (6B6C-1) | II | ≥256 | 32 | 256 | ≥256 | 32 | 1 (25,600) | |

| A2 (4E5) | II | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1 (160) | |

| A3 (1A5D 1) | II | 4 | 4 | 1 (160) | ||||

| A5 (1B7) | II | 128 | 64 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 1 (25,600) | |

| C1 (1B4C-2) | I | 32 | 256 | 256 | 16 | 64 | 512 | 1 (51,200) |

| C2 (4A5C-8) | I | 4 | 4 | 1 (80) | ||||

| C3 (2B3A-1) | I | 8 | 16 | 16 | ≥16 | 16 | 8 | 1 (1,600) |

| C4 (9A4D-1) | I | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 512 | 128 | 1 (5,120) |

| B2 (9A3D-8) | III | 256 | 1 (25,600) | |||||

| B3 (10A4D-2) | III | 16 | 8 | ≥256 | 1 (25,600) | |||

| B4 (1A1D-2) | III | 8 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 16 | 128 | 1 (51,200) |

| ?(4A2B-4) | ? | 4 | 16 | 64 | 1 (640) | |||

| ? (10A1D-2) | ? | 16 | 1 (320) | |||||

| ? (1A6A-8) | ? | 1 (2,560) | ||||||

| Cap (1A2A-1) | Capsid | 1 (20) | ||||||

Fold reduction or increase (bold) in MAb end-point titer with mutated DEN2 E proteins compared with the pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1-derived, wild-type chimeric E protein. Blank means two-fold or less difference in titers. ?, unknown.

E-protein amino acid location of cysteine residues involved in disulfide bridge.

Reactivity on LLC-MK2 cells transformed with the pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1 plasmid expressing the modified, chimeric DEN2 16681 prM/E protein. For the purpose of comparing fold differences in mutant reactivity, activity of MAbs on the pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1-transformed cells was set at 1. The actual reciprocal end-point titer of each MAb on the pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1-derived DEN2 prM/E protein-transformed cells is shown in parentheses.

Of the four DII epitopes examined, the reactivity of three anti-DII MAbs (A1, A2, and A5) was reduced by elimination of any of the DII or DIII SS bonds (SS2, SS3, SS4, SS5, and SS6). One DII MAb (A3) was affected by SS2 and SS3 elimination only, maintaining reactivity with the SS4 and SS5 DII mutants. The sensitivity of DII epitopes to SS-bond elimination is consistent with the lower level of binding DII MAbs have with viral E protein that has been reduced with β-mercaptoethanol (17). Interestingly, the reactivity of the MAbs defining the A1 and A5 epitopes, but not the A2 and A3 epitopes, was significantly enhanced by fixing plasmid-transformed cells in acetone (endpoint titers on unfixed cells were 6,400 for both MAbs versus 25,600 on fixed cells). Anti-A1, -A2, and -A5 MAbs block fusion, but only anti-A1 and -A5 recognize native virus, suggesting that anti-A1 and -A5 MAbs have a different mechanism of fusion blocking than anti-A2 MAbs.

The increased reactivity of epitopes A1 and A5 following acetone fixation may be related to their accessibility in prM-containing virions. The reactivity of MAbs specific for these epitopes is reduced in virions containing prM protein (6). It has been shown previously that the A1 and A5 epitopes cosegregate on a proteolytic or synthetic fragment of the E protein containing aa 1 to 120 (1, 17, 19). Recent cryoelectron-microscopic studies of prM-containing DEN2 virus particles confirm that this region of the E protein interacts with the prM protein (26). Our analysis would suggest that an increase in cell membrane permeability following acetone fixation better exposes these epitopes even though the prM cleavage in these transformed cells is not efficient (4). These binding differences could also be due to differences in epitope expression in virions versus virus-infected cell membranes. For either case it should be noted that the original epitope mapping studies of the DEN2 virus E protein used purified virus grown in C6/36 cells, a cell type in which the prM→M cleavage is not efficient, and most released virions contain large amounts of prM. Because of this the presence of prM alone in the membrane of cells transformed with pCB8D2-2J-2-9-1 plasmid should not alter the expression of the DEN2 E protein epitopes as previously defined in the C6/36-derived virus.

The pattern of epitope A1 sensitivity to reduction of the DII SS bonds is also of interest. This epitope is most sensitive to elimination of SS2, SS4, and SS5, which are the SS bonds necessary to maintain the overall conformation of DII. Epitope A1 is at least eightfold less sensitive to elimination of SS3, which is the SS bond that maintains the secondary structure in the immediate vicinity of the flavivirus fusion motif (aa 98 to 110). The location of SS3 (aa 74 to 105) suggests that a peptide as small as 30 aa might contain enough native structure of the fusion motif to successfully mimic this region. If this is true, then antipeptide antibodies specific for this region might successfully block fusion with some degree of specificity. A synthetic peptide corresponding to DEN2 aa 79 to 99 has been shown previously to elicit anti-DEN2 virus antibody and also low-level virus-neutralizing antibody to Murray Valley encephalitis virus (18, 19). Antipeptide antibodies reactive with this region of DII have also been used to demonstrate that the fusion motif of the E protein becomes exposed after low-pH-catalyzed conformational change (19). We are currently pursuing use of peptide mimicry and antipeptide antibodies to block virus-mediated cell membrane fusion.

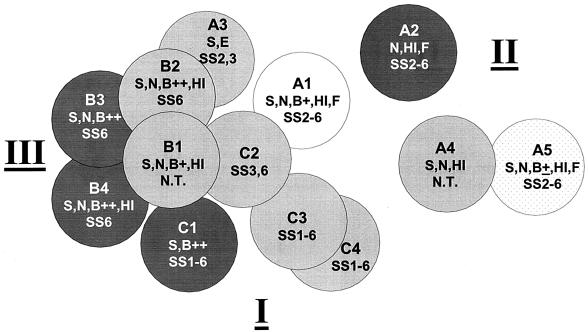

Our results confirm that appropriate expression of DIII is most dependent on SS6 (12). The reactivity of MAbs 4B2B-4 and 10A1D-2, whose epitopes have not been completely defined but have biochemical characteristics similar to those of DIII epitopes, were very similar to the other DIII-reactive MAbs in their SS-bond sensitivities, providing additional evidence that 4B2B-4 and 10A1D-2 define DIII epitopes. The binding of MAb 1A6A-8 was not affected by any SS-bond elimination, which is consistent with its ability to bond well to the E protein in reduced immunoblots. A comparison of epitope sensitivity to SS-bond abolition and their other functional activities is shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Effects on epitope reactivity in mutated plasmids. This balloon diagram was based on a similar epitope mapping diagram published previously (17). Overlapping circles indicate spatial proximity of epitopes as determined in antibody competitive binding assays. Antigenic regions containing epitopes A1 to A5 in DII, B1 to B4 in DIII, and C1 to C4 in DI are shown. Colors: light gray, type-specific epitopes; dark gray, subcomplex-reactive epitopes; stippled, subgroup-reactive epitopes; and white, group-reactive epitopes. Abbreviations: S, epitope accessible on protein surface; N, epitope that elicits virus-neutralizing antibody; B, epitope that elicits antibody that blocks virus adsorption (low-activity, B±; high activity, B++); E, epitope that elicits antibody that enhances virus adsorption; HI, epitope that elicits antibody that blocks hemagglutination; F = epitope that elicits antibody that blocks virus-mediated cell membrane fusion; SS1-6, SS bond (1 to 6) eliminated; N.T., not tested. Biological activities are as described in reference 17, and adsorption blocking activities are as described in reference 5.

With mounting experimental evidence implicating DIII in interaction with cell receptors, it is not surprising that SS6 (which stabilizes a region of DIII thought to function as the receptor binding portion of the E protein) is critical to appropriate epitope structure. The sensitivity of epitopes B3 and B4 to abolition of the DII SS bonds might be due to the close proximity of DII and DIII in either the E-protein monomer or homodimer. The presence of many type-specific epitopes in DIII and its relatively stable conformation suggest that it might be useful as a virus-specific antigen. It has been shown by others that DIII can be independently expressed and retain much of its biological activity (3, 10, 21, 22, 24).

The results presented here correlate closely with previously published information concerning the antigenic structure of the flavivirus E protein; however, some alternative explanations for these results could be considered. It is possible that the reduction in some MAb activities with these mutant E proteins could be due to misfolding of the E protein due to novel interactions of the orphan sulfhydryl group remaining from the eliminated SS-bond with other regions of the protein or to simple degradation of the E protein. This concern for reactive orphan sulfydryl groups has not been substantiated in a number of other studies evaluating the effects of SS-bond elimination on protein function. This may be because the sulfhydryl R group in Cys has a pKa of 8.3. The orphan Cys sulfhydryl R group in our mutants should be fully hydrogenated, and less reactive, at the pH (7.4) at which these experiments are performed. We elected to minimize the possibilities of intrachain SS bond mismatches by mutating only one SS bond at a time. Even if misfolding occurred, eukaryotic cells have a system for retaining misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum and cycle these defective proteins back to the ubiquitin-proteosome system for hydrolysis (15). Since MAb-reactive (and therefore intact) E protein can be transported and identified on the cell surface with all of these SS-bond mutants, it is likely that any reduction in reactivity of MAbs with the mutant E proteins in these experiments was not the result of drastically misfolded or degraded protein.

The data presented here also support the concept that the prM and E proteins are normally associated in the SS-bond mutants. Previous studies with TBE virus have shown that there are two regions of the E protein important for oligimerization with prM protein: aa 431 to 449 and aa 450 to 472, which lie in the E-protein stem region (2). Neither of these stem regions contains SS bonds, and thus, they had no introduced Cys mutations in the present study. Further analysis of TBE virus E protein expressed without prM produced a protein with an authentic DI and DIII; however, an anti-A5 epitope was less reactive (11). Unfortunately, no other DII-reactive MAbs were used in this TBE study to better discern total DII conformation. In the present study, when a reduction of MAb binding was detected in one domain, cell surface binding was retained by MAbs defining the other two domains, and binding was frequently observed with other MAbs defining the primary affected domain as well. In addition, most MAbs (e.g., 1A6A-8) reacted similarly with all SS-bond mutants regardless of whether cells were tested acetone fixed or unfixed (data not shown), suggesting that maturation and transport of the prM/E heterodimer were occurring normally.

The results presented here help explain why attempts to mimic accurately flavivirus E-protein epitopes on short synthetic peptides have, in general, met with limited success (18, 19). The general conformational stability of the DII fusion motif and the DIII receptor binding domain, however, suggest possible targets in the E protein for the development of effective and specific antiflavivirus therapies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaskov, J. G., H. M. Geysen, and T. J. Mason. 1989. Serologically defined linear epitopes in the envelope protein of dengue 2 (Jamaica strain 1409). Arch Virol. 105:209-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allison, S. L., K. Stiasny, K. Stadler, C. W. Mandl, and F. X. Heinz. 1999. Mapping of functional elements in the stem-anchor region of tick-borne encephalitis virus envelope protein E. J. Virol. 73:5605-5612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhardwaj, S., M. Holbrook, R. E. Shope, A. D. Barrett, and S. J. Watowich. 2001. Biophysical characterization and vector-specific antagonist activity of domain III of the tick-borne flavivirus envelope protein. J. Virol. 75:4002-4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, G. J., A. R. Hunt, D. A. Holmes, T. Springfield, T.-S. Chiueh, J. T. Roehrig, and D. J. Gubler. 2003. Enhancing biosynthesis and secretion of premembrane and envelope proteins by the chimeric plasmid of dengue virus type 2 and Japanese encephalitis virus. Virology 306:170-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crill, W. D., and J. T. Roehrig. 2001. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to domain III of dengue virus E glycoprotein are the most efficient blockers of virus adsorption to Vero cells. J. Virol. 75:7769-7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guirakhoo, F., R. A. Bolin, and J. T. Roehrig. 1992. The Murray Valley encephalitis virus prM protein confers acid resistance to virus particles and alters the expression of epitopes within the R2 domain of E glycoprotein. Virology 191:921-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinz, F. X., and J. T. Roehrig. 1990. Immunochemistry of flaviviruses, p. 289-305. In M. H. V. Van Regenmortel and A. R. Neurath (ed.), Immunochemistry of viruses: the basis for serodiagnosis. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 8.Henchal, E. A., J. M. McCown, D. S. Burke, M. C. Seguin, and W. E. Brandt. 1985. Epitopic analysis of antigenic determinants on the surface of dengue-2 virions using monoclonal antibodies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 34:162-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin, B., C. R. Parrish, J. M. Murray, and P. J. Wright. 1994. Localization of a neutralizing epitope on the envelope protein of dengue virus type 2. Virology 202:885-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin, C. W., and S. C. Wu. 2003. A functional epitope determinant on domain III of the Japanese encephalitis virus envelope protein interacted with neutralizing-antibody combining sites. J. Virol. 77:2600-2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorenz, I. C., S. L. Allison, F. X. Heinz, and A. Helenius. 2002. Folding and dimerization of tick-borne encephalitis virus envelope proteins prM and E in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Virol. 76:5480-5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mason, P. W., M. U. Zugel, A. R. Semproni, M. J. Fournier, and T. L. Mason. 1990. The antigenic structure of dengue type 1 virus envelope and NS1 proteins expressed in Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Virol. 71:2107-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modis, Y., S. Ogata, D. Clements, and S. C. Harrison. 2003. A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:6986-6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nowak, T., and G. Wengler. 1987. Analysis of disulfides present in the membrane proteins of the West Nile flavivirus. Virology 156:127-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plemper, R. K., and D. H. Wolf. 1999. Retrograde protein translocation: ERADication of secretory proteins in health and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:266-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rey, F. A., F. X. Heinz, C. Mandl, C. Kunz, and S. C. Harrison. 1995. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 A resolution. Nature 375:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roehrig, J. T., R. A. Bolin, and R. G. Kelly. 1998. Monoclonal antibody mapping of the envelope glycoprotein of the dengue 2 virus, Jamaica. Virology 246:317-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roehrig, J. T., A. R. Hunt, A. J. Johnson, and R. A. Hawkes. 1989. Synthetic peptides derived from the deduced amino acid sequence of the E-glycoprotein of Murray Valley encephalitis virus elicit antiviral antibody. Virology 171:49-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roehrig, J. T., A. J. Johnson, A. R. Hunt, R. A. Bolin, and M. C. Chu. 1990. Antibodies to dengue 2 virus E-glycoprotein synthetic peptides identify antigenic conformation. Virology 177:668-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roehrig, J. T., J. H. Mathews, and D. W. Trent. 1983. Identification of epitopes on the E glycoprotein of Saint Louis encephalitis virus using monoclonal antibodies. Virology 128:118-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmons, M., W. M. Nelson, S. J. Wu, and C. G. Hayes. 1998. Evaluation of the protective efficacy of a recombinant dengue envelope B domain fusion protein against dengue 2 virus infection in mice. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 58:655-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmons, M., K. R. Porter, J. Escamilla, R. Graham, D. M. Watts, K. H. Eckels, and C. G. Hayes. 1998. Evaluation of recombinant dengue viral envelope B domain protein antigens for the detection of dengue complex-specific antibodies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 58:144-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wengler, G. 1989. An analysis of the antibody response against West Nile virus E protein purified by SDS-PAGE indicates that this protein does not contain sequential epitopes for efficient induction of neutralizing antibodies. J. Gen. Virol. 70:987-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White, M. A., D. Liu, M. R. Holbrook, R. E. Shope, A. D. Barrett, and R. O. Fox. 2003. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of Langat virus envelope protein domain III. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59:1049-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winkler, G., F. X. Heinz, and C. Kunz. 1987. Characterization of a disulphide bridge-stabilized antigenic domain of tick-borne encephalitis virus structural glycoprotein. J. Gen. Virol. 68:2239-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, Y., J. Corver, P. R. Chipman, W. Zhang, S. V. Pletnev, D. Sedlak, T. S. Baker, J. H. Strauss, R. J. Kuhn, and M. G. Rossmann. 2003. Structures of immature flavivirus particles. EMBO J. 22:2604-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]