Abstract

An inhibitor of tissue factor-induced coagulation was rediscovered in the 1980’s and subsequently named tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI). Three isoforms of TFPI are transcribed through alternative mRNA splicing: TFPIα, which contains an acidic aminoterminus followed by three tandem Kunitz-type protease inhibitor domains and a basic carboxyterminus; TFPIβ, in which the Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminus of TFPIα are replaced with a different carboxyterminus containing a glycosyl phosphatidyl inositol (GPI) anchor; and TFPIδ, which is truncated following the Kunitz-2 domain. The microvascular endothelium is thought to be the principal source of TFPI and TFPIα is the predominant isoform expressed in humans. TFPIα, apparently attached to the surface of the endothelium in an indirect GPI-anchor-dependent fashion, represents the greatest in vivo reservoir of TFPI. The Kunitz-2 domain of TFPI is responsible for factor Xa inhibition and the Kunitz-1 domain is responsible for factor Xa-dependent inhibition of the factor VIIa/tissue factor catalytic complex. The anticoagulant activity of TFPI in one-stage coagulation assays is due mainly to its inhibition of factor Xa through a process that is enhanced by protein S and dependent upon the Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminal domains of full-length TFPIα. Carboxyterminal truncated forms of TFPI as well as TFPIα in plasma, however, inhibit factor VIIa/tissue factor in two-stage assay systems. Studies in gene-disrupted mice demonstrate the physiological importance of TFPI.

2. INTRODUCTION

As early as 1922, Loeb suggested that serum contained a moiety that inhibits the procoagulant activity of tissue extracts (1, 2). Later, Thomas (3) and Schneider (4) independently demonstrated the in vivo correlate of this observation by showing that the incubation of tissue thromboplastin with serum prevented its lethal effect when infused into animals. Thomas (3) also noted that the inhibitory effect of serum required the presence of calcium ions, that the inhibitor appeared to bind to thromboplastin, and that the effect could be reversed by calcium ion chelators. The calcium ion requirement and reversibility of the thromboplastin inhibition were subsequently confirmed by in vitro coagulation assays (5–9). In 1957, Hjort (10) reported that the previously described serum inhibitor of thromboplastin recognized the factor VIIa-Ca2+-tissue factor complex, which he termed convertin, rather than factor VII (proconvertin) or thromboplastin alone. He ascribed the calcium dependence and reversibility of the inhibition by calcium chelation to the requirement for convertin formation and, using indirect means, suggested that the binding of the inhibitor to convertin was calcium ion-dependent as well.

Nearly 25 years later, Carson reported that plasma lipoproteins inhibited the catalytic activity of the factor VIIa/tissue factor complex (11) and Dahl et al. showed that the anticonvertin activity of Hjort eluted in two high-molecular-weight peaks on gel filtration of plasma, consistent with an association with plasma lipoproteins (12). Subsequently, Morrison and Jesty (13) demonstrated that the activation of factor IX and factor X in plasma was incomplete following the addition of tissue factor and that this apparent inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor enzymatic activity was directly related to the presence of factor X or brief pretreatment of the plasma with factor Xa. Rapaport and colleagues (14) then confirmed that both factor X and an inhibitor present in the total lipoprotein fraction of plasma were required for this apparent inhibition of tissue factor-mediated coagulation. Additional studies corroborated the earlier work (15–18) and went on to show that the inhibitor produced factor Xa-dependent feedback inhibition of the factor VIIa-tissue factor complex (19, 20). The inhibitor was initially purified from the conditioned media of HepG2 (human hepatoma) cells (21) and subsequently its cDNA cloned (22) and the organization of its gene determined (23, 24).

This inhibitor has been called antithromboplastin, anticonvertin, the factor Xa-dependent factor VIIa-tissue factor inhibitor, tissue factor inhibitor, extrinsic pathway inhibitor, and lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor. In 1991, a subcommittee of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis settled on the currently used name, tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI).

Although TFPI may play additional roles in innate immunity, microbial defense, inflammation, angiogenesis, lipid metabolism, and cellular signaling, proliferation, migration, and apoptosis, the focus of this review is its regulation of coagulation.

3. ISOFORMS

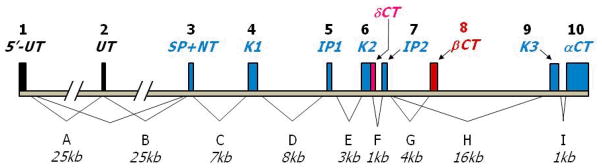

The TFPI gene spans approximately 90 kb on the long arm of chromosome 2 (q32) and contains ten exons and nine introns (Figure 1) [(23, 24), GenBank: NC_000002.11]. All the splice junctions between exons are of the same type (type 1), which suggests that the TFPI gene was assembled during evolution through a process of gene duplication and exon shuffling. Three alternatively transcribed isoforms of TFPI have been identified.

Figure 1. Structure of the human TFPI Gene.

The TFPI gene spans 90 kb and contains 10 exons (vertical boxes) and 9 introns that encode for three isoforms. Exons are labeled numerically (top), introns alphabetically (bottom). Translated exons encoding TFPIα are filled in blue. Alternatively spliced exons leading to the generation of TFPIδ and TFPIβ are filled in magenta and red, respectively. Exons 1 and 2 encode 5′ untranslated (5′UT) sequences with alternative splicing resulting in the absence of exon 2 in some messages. Exon 3 encodes the signal peptide and amino terminal peptide (SP+NT). Exons 4, 6 and 9 encode Kunitz domains 1 (K1), 2 (K2) and 3 (K3), respectively and intervening peptide sequences that link the Kunitz domains are encoded by exons 5 (IP1) and 7 (IP2). A run-on of exon 6 into intron F (magenta) encodes the short TFPIδ variant carboxyl terminus (δCT). The TFPIβ carboxy-terminal peptide (βCT) is encoded by exon 8 (red) and splicing of exon 7 to exon 8 occurs to generate the TFPIβ message. In the TFPIα message exon 9 is directly spliced to exon 7 (K3) and to exon 10 (αCT), thereby encoding the Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminus of the TFPIα protein.

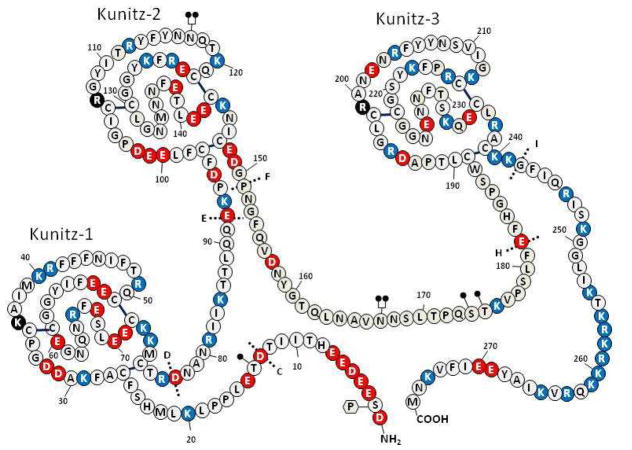

TFPIα (GenBank NM_006287.4) is the originally isolated form of TFPI (Figure 2). Exons 1 and 2 encode 5′ untranslated regions and due to alternative splicing exon 2 is absent in some messages. Exon 3 encodes the signal peptide, which is removed during processing of the protein, and the aminoterminus of the mature TFPI. The TFPIα molecule contains three tandem Kunitz-type proteinase inhibitor domains that are encoded by separate exons (4, 6, and 9) and intervening peptides between Kunitz domains that are encoded by exons 5 and 7. The carboxyterminus of the TFPIα protein and an extensive 3′ untranslated region are encoded by exon 10.

Figure 2. Structure of TFPIα.

Amino acids are identified by the single letter code (encircled). Positively charged amino acids are shown in red, negatively charge amino acids in blue and neutral amino acids in white (histidine residues are considered uncharged). The Kunitz domains are labeled and the basic P1 residues at the active site cleft for each domain is shown in black. N-linked glycosylation sites are denoted at N117 and N167 by

and O-linked glycosylation sites are denoted at T14, S174 and T175 by

and O-linked glycosylation sites are denoted at T14, S174 and T175 by

. Partial phosphorylation at Ser2 is also shown

. Partial phosphorylation at Ser2 is also shown

. The sites of introns in the TFPI gene are labeled with dotted lines and capital letters.

. The sites of introns in the TFPI gene are labeled with dotted lines and capital letters.

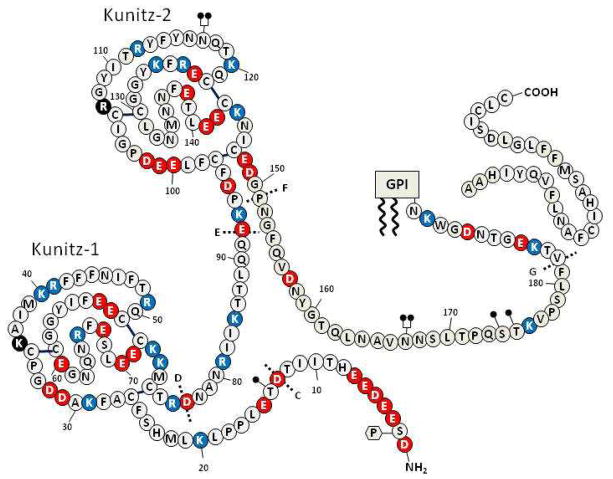

An alternatively spliced form of TFPI mRNA, called TFPIβ was initially detected in mice (25). In human TFPIβ mRNA (GenBank NM_001032281.2), exon 8, which contains a stop codon and polyadenylation signal, is used in place of exons 9 and 10 and this leads to the production of an alternative carboxyterminus inserted at residue 182 that directs the attachment of a glycosyl phosphatidyl inositol (GPI) anchor (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Structure of TFPIβ.

Symbols as denoted in the legend of Figure 2. The GPI-anchor is shown attached to mature TFPIβ along with the released carboxyterminal peptide.

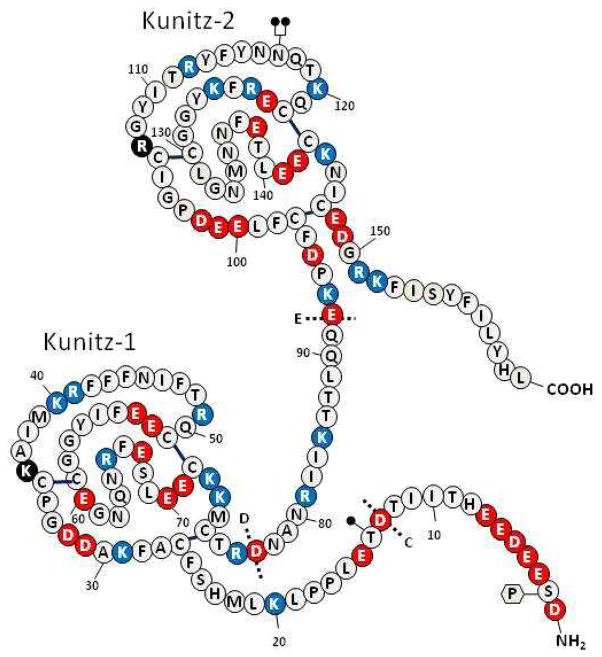

An additional variant form of hTFPI mRNA (TFPIδ) is listed in the GenBank (human: AB209866.1; chimpanzee: XM_001161803.1) and is consistent with intron F retention (Figure 4). Within the intron are a downstream stop codon and a polyadenylation signal. This message generates a truncated form of TFPI with the insertion of a new 12 amino acid C-terminus at residue 151 following the Kunitz-2 domain of TFPIα.

Figure 4. Structure of TFPIδ.

Symbols as denoted in the legend of Figure 2.

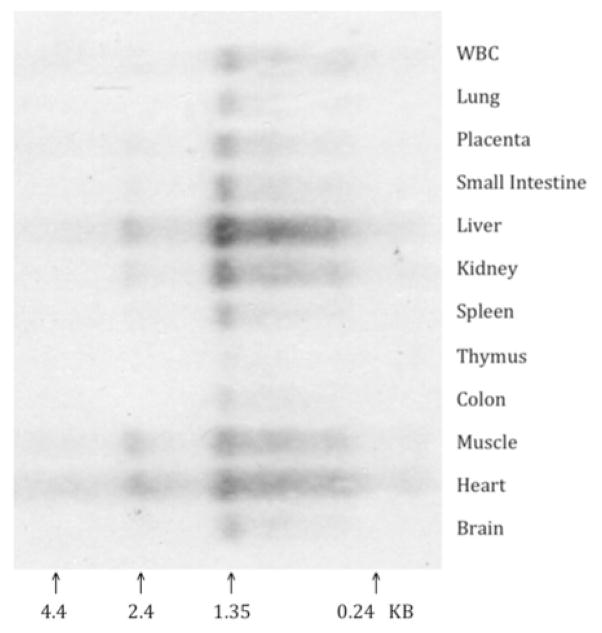

In human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and endothelial-like cell lines (EAhy926, ECV304) the ratio of TFPIα/TFPIβ mRNA varies between 5 and 10 (26). The TFPIα protein has been purified from the conditioned media of HepG2 cells and plasma (21, 27, 28), but TFPIβ protein has thus far only been identified indirectly in ECV304 cells (a bladder cancer cell line with some endothelial characteristics) (26, 29, 30) and reportedly is not produced by EAhy926 cells (31). Tissue northern blot analysis shows predominant TFPIδ mRNA in the liver in contrast to the expression of TFPIα mRNA, which is highest in vascular tissues like the lung and placenta (Figure 5). Whether the northern result, however, represents significant expression of TFPIδ, simply a splicing error that occurs more commonly in the liver, or a mechanism for regulating TFPI expression through unproductive splicing and translation (RUST) and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) (32) is not clear and detection of the TFPIδ protein has not yet been reported.

Figure 5. TFPIδ mRNA in human tissues.

Tissue northern blot of oligo (dT) isolated mRNA hybridized with a labeled probe specific for TFPIδ mRNA.s

4. STRUCTURE

The primary structure of TFPIα is unique (Figure 2) (22). After a 24 or 28 amino acid signal peptide, the mature protein has 276 residues (32 kDa) and contains an acidic aminoterminal region followed by three tandem Kunitz-type protease inhibitory domains and a basic carboxyterminal region. The addition of post-translational modifications results in an observed mass of ~43 kDa. TFPIα isolated from plasma contains sialyl complex-type N-linked carbohydrate at Asn117 and Asn167 and (sialyl) Galβ1-3GalNAc O-linked carbohydrate linked to Thr175, and partially to Thr14 and Ser174 (33). Interestingly, the sugar chains linked to Asn117 appear to contain a sialyl Lewis X structure. The oligosaccharides in TFPI expressed by certain cells in vitro (e.g. rabbit endothelial cells, HEK293 cells) are sulfated (34–36), but sulfated sugar chains were not detected in TFPIα isolated from human plasma (33). Ser2 is partially phosphorylated in the TFPI expressed by some cells in tissue culture, likely through the action of casein kinase II (37), and it has been estimated that ~15% of TFPIα isolated from plasma is phosphorylated (33). These post-translational modifications do not appear to significantly affect the known proteinase inhibitory properties of TFPIα (38).

TFPIβ lacks the Kunitz-3 and basic carboxyterminal domains of TFPIα and in their place contains a 42 amino acid carboxyterminal sequence inserted following residue 181 of TFPIα (Figure 3). This new carboxyterminal sequence is predicted to direct the proteolytic cleavage of the peptide following N193 with the attachment of a GPI anchor. The protein mass of TFPIβ is less than that of TFPIα (22 versus 32 kDa), but it migrates on SDS-PAGE at the same apparent molecular weight as TFPIα (43 kDa) due to greater sialylation of its O-linked carbohydrate (30).

Kunitz-type inhibitors appear to act by the standard mechanism (39) in which the inhibitor feigns to be a good substrate, but, after the enzyme binds, the subsequent cleavage between the P1 and P1′ amino acid residues at the active site cleft of the inhibitor occurs slowly or not at all. The P1 residue is an important determinant of the specificity of these inhibitors, and alterations of the residue in the P1 position can profoundly affect their inhibitory activity. In kinetic terms, Kunitz-type inhibitors typically produce slow, tight-binding, competitive, and reversible enzyme inhibition.

In the reaction, the Kunitz-type inhibitor forms an initial “encounter” complex (EI) with the enzyme and this complex then “slowly” isomerizes to a much tighter form (EI*). “Slow” implies that the final degree of inhibition does not occur immediately, and “tight-binding” means that inhibition occurs at a concentration of the inhibitor that is near to that of the enzyme.

Experiments in which the P1 residue of each Kunitz domain in TFPIα was individually altered have shown that the Kunitz-2 domain of TFPI mediates factor Xa binding and inhibition, whereas the Kunitz-1 domain is necessary for the inhibition of factor VIIa in the factor VIIa-tissue factor complex (40). Alteration of the P1 residue in the third Kunitz domain does not affect either of these functions of TFPI. Studies examining the inhibitory properties of the isolated Kunitz domains of TFPI have reached the same conclusions and have shown that the Kunitz-3 domain lacks proteinase inhibitory activity (41). The placement of serine at residue 220 in Kunitz-3 (residue 36 in aprotinin numbering), instead of the conserved glycine present in Kunitz domains with proteinase inhibitory activity, likely induces a conformational change that restricts the entry of the Kunitz domain into the substrate-binding pocket of serine enzymes (41, 42). TFPIα also inhibits trypsin and chymotrypsin reasonably well and inhibits cathepsin G, plasmin, and activated protein C poorly (43, 44); the physiologic significance of these inhibitory reactions, however, is doubtful.

5. DISTRIBUTION

The microvascular endothelium is thought to be the major source of TFPI in vivo. Northern blot analysis of tissues shows the highest TFPI mRNA levels in the placenta and lung and the lowest in the brain (45). Studies of normal tissues have detected TFPI protein in the endothelium of the microvasculature, smooth muscle cells, monocytes/macrophages, megakaryocytes/platelets, mesangial cells, fibroblasts, microglia, cardiomyocytes, and mesothelial cells (46–55).

5.1. Plasma TFPI

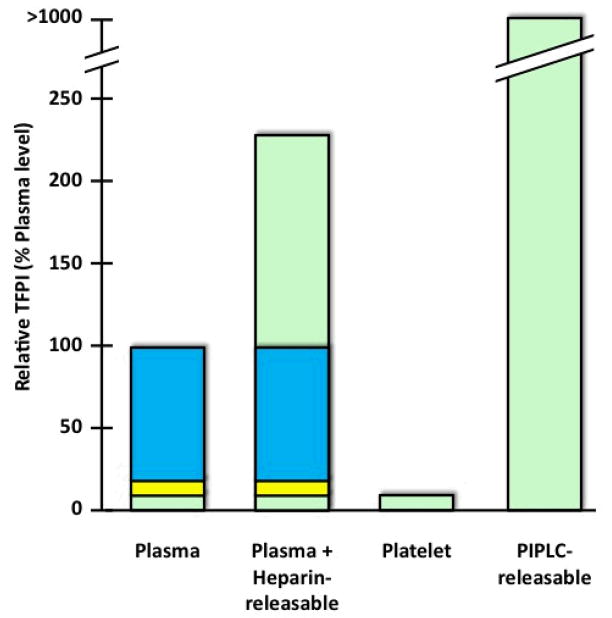

The mean plasma TFPI concentration in normal individuals is ~70 ng/mL (1.6 nM) [e.g. (56)]. Most of the circulating TFPI is bound to lipoproteins (~80%) (18, 27, 57) (Figure 6). Plasma concentrations of TFPI correlate with LDL levels because LDL is a major carrier; plasma concentrations increase with diet-induced hypercholesterolemia in monkeys and decrease in response to statin therapy in individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia (58–61). Individuals with abetalipoproteinemia lack LDL and have low levels (~25%) of TFPI in plasma (62), but do not have a prothrombotic phenotype, suggesting that non-lipoprotein-associated forms of TFPI in plasma and/or TFPI at other endogenous locales are physiologically important.

Figure 6. Distribution of TFPI.

In plasma, carboxyterminal truncated forms of TFPI are bound to lipoproteins and comprise ~80% of circulating TFPI (blue). Whether these forms represent extensively truncated forms of TFPIα, TFPIβ or TFPIδ has not been determined. “Free” forms of TFPI (~20%) contain the Kunitz-3 domain and include carboxyterminal truncated forms of TFPIα (~10%) (yellow) and full-length TFPIα (~10%) (green). Following heparin treatment in vivo, the level of total TFPI in plasma increases 1.5–3.0-fold and the released TFPI is full-length TFPIα. Platelets carry a level of full-length TFPIα that is equivalent to that present in plasma. At sites where platelets aggregrate, the contribution of platelets to the local concentration of full-length TFPIα could exceed the level of full-length TFPIα in plasma by >30-fold. Based on studies of cultured endothelial cells, the quantity of surface TFPI released by PIPLC greatly exceeds (>5-fold) that released by heparin. The PIPLC-releasable TFPI appears predominantly to be full-length TFPIα; PIPLC-induced release of TFPIβ has not yet been documented in endothelial cells.

Predominant forms of TFPI in plasma have molecular weights of 34 and 41 kDa, and less abundant forms of higher molecular mass are also present (27, 63). The size heterogeneity of plasma TFPI reflects, in part, the carboxyterminal truncation of the TFPIα molecule and the formation of mixed disulfide complexes with apolipoprotein-AII and potentially other proteins (63). The major form of TFPI bound to LDL has a molecular weight of 34 kDa and lacks the distal portion of full-length TFPIα, including at least a large portion of the Kunitz-3 domain. The 41 kDa form of TFPI that circulates with HDL appears to represent a similar carboxy-truncated form of TFPI that is disulfide-linked to monomeric apolipoprotein-AII. Whether the lipoprotein-associated TFPIs are extensively carboxy-truncated forms of TFPIα or modified forms TFPIβ or TFPIδ has not been established and the mechanism underlying the association of 34 kDa TFPI with LDL has not been determined.

TFPI antigen assays utilizing antibodies against the Kunitz-3 domain of TFPIα do not recognize lipoprotein-bound TFPI and measure “free” TFPI, ~20% of total plasma TFPI (64, 65) (Figure 6). These assays detect forms of TFPIα with limited carboxyterminal truncation produced by an as yet unidentified proteinase(s) and full-length TFPIα, which probably represents ~50% of the “free” TFPI or ~10% of total plasma TFPI. Whether TFPIβ, enzymatically released or shed in membrane vesicles from cell surfaces, circulates in human plasma is not known.

In vitro experiments have shown that TFPIα can be proteolytically degraded by a variety of proteinases, including thrombin, plasmin, neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, factor Xa (when at molar excess over TFPIα), cell-derived matrix metalloproteinases, and bacterial omptins (55, 66–72). Plasmin-mediated degradation of TFPI in plasma and on the monocyte surface has been demonstrated in patients following thrombolytic therapy and likely on the cells of the lung in septic baboons (73, 74). The degradation of TFPI by neutrophil proteinases, especially elastase, has been shown to enhance microvascular coagulation thereby limiting the tissue dissemination of bacterial pathogens, but to also increase large vessel thrombosis (75). The cleavage of TFPI by neutrophil elastase is facilitated by neutrophil-derived externalized nucleosomes, which form neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that serve to co-localize neutrophil elastase and TFPI.

Plasma concentrations of “free” and full-length TFPIα are reduced in the plasmas of patients with factor V deficiency, protein S deficiency, and perhaps factor VIII deficiency (76–79). Apparent binding interactions between full-length TFPIα and factor V and protein S have been demonstrated in plasma and by surface plasmon resonance in purified systems (76, 77, 80, 81). Whether these interactions affect the expression, proteolytic degradation, or clearance of TFPIα remains to be determined.

5.2. Platelet TFPI

TFPIα is expressed by megakaryocytes, stored in platelets at a site separate from α granules, and released in response to thrombin and other agonists (82, 83). In “coated” platelets produced by dual agonist stimulation (e.g. thrombin/collagen, thrombin/convulxin), a proportion of the released TFPIα remains bound and functional at the activated platelet surface (83). Similar to other ligands (e.g. factor V, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor) detected on the surface of coated platelets, transglutaminase inhibitors prevent this retention of surface TFPIα (83).

The full-length TFPIα carried in platelets is 8–10% of the total TFPI in blood (82, 83), which is comparable to the quantity of soluble full-length TFPIα in plasma (Figure 6). Thus, it is likely that platelets are a major source of full-length TFPIα, the most anticoagulantly active form of TFPI (see below), at local sites of coagulation where platelets aggregate. The total TFPI concentration in the blood exuding from bleeding time wounds increases 3.5-fold by the time the bleeding stops (~9 min.) (82). If this increase is due to the release of TFPIα from stimulated platelets this would represent a >30-fold increase in local concentrations of full-length TFPIα. On the other hand, polyphosphates released from the dense granules of stimulated platelets modestly reduce the anticoagulant effects of TFPIα in plasma coagulation assays, apparently in part through their enhancement of factor V activation (84, 85).

5.3. Cell-associated TFPI

Several reports have documented the low affinity, heparin-inhibitable binding of TFPIα to cells potentially mediated by surface proteoglycans, the internalization and degradation of TFPIα through the action of the LDL-receptor-related protein (LRP), and the rapid clearance of TFPIα in animals [e.g. (86–95)]. These studies used recombinant TFPIα (rTFPIα) that lacked the post-translational modifications found in mammalian TFPIα. In contrast, the rTFPIα produced by at least one mammalian cell line (mouse C127) does not bind to cells or interact with LRP in the same fashion as E.coli rTFPIα and is cleared from plasma at a 10-fold slower rate (96). Therefore, the studies that used non-mammalian derived TFPI should probably be viewed with considerable caution.

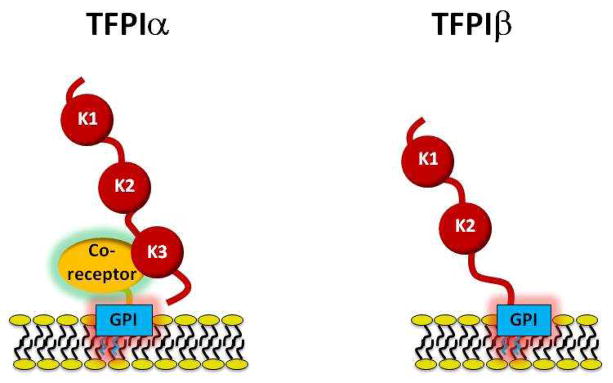

5.3.1. Cell Surface TFPI

A substantial fraction of the TFPI produced by endothelial cells remains at the cell surface, associates with caveolae, and is released by phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PIPLC) (Figures 6 and 7) (26, 29–31, 97–100). These are properties of GPI-anchored proteins. The predominant form of TFPI released from the surface of endothelial cells by PIPLC is TFPIα. The amino acid sequence of TFPIα, however, does not contain the appropriate motifs to direct the canonical carboxyterminal cleavage and attachment of a GPI anchor and the TFPI released from the surface of endothelial cells by PIPLC contains the carboxyterminus of full-length TFPI (31).

Figure 7. Cell Surface TFPI.

Left: TFPIα appears to attach to the cell membrane by binding to a GPI-anchored co-receptor. The Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminal domains of TFPIα are involved in its interaction with the co-receptor. Right: TFPIβ attaches to the cell membrane through an intrinsic GPI-anchor. The Kunitz-1, Kunitz-2, and Kunitz-3 domains of TFPI are labeled K1, K2, and K3, respectively.

The cell surface binding of TFPIα therefore appears to involve its interaction with a separate, as yet unidentified, GPI-anchored co-receptor(s) (26, 29, 97–100) that may control its cellular trafficking and surface expression (31). Very little rTFPIα is detected on the surface of transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (26, 29) and human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells (101) suggesting that: 1) these cells do not express the co-receptor; 2) these cells express a form of TFPIα lacking a post-translational modification that is required for co-receptor binding; or 3) the interaction between TFPIα and the co-receptor demonstrates species-specificity in the case of CHO cells. In transfected cells that do display PIPLC-releasable rTFPIα (e.g. mouse C127 cells), the surface binding requires the Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminal domains of TFPIα and a single mutation of the P1 residue in Kunitz-3 (R199L) substantially reduces the cell surface localization of rTFPIα (29).

Treatment of cultured endothelial cells with heparin or heparitinase does not perceptibly reduce surface TFPI (26, 29, 98). PIPLC treatment releases ~80% of the surface TFPI and the remaining TFPI can then be removed by subsequent heparin treatment (26, 29, 31). This suggests that the interaction of TFPI with the cell surface is complex and may involve more than a single entity. The surface distribution of exogenously offered E. coli rTFPIα does not mirror that of endogenously expressed TFPI (99) and, although the E. coli rTFPIα is a potent inhibitor cell surface factor VIIa/tissue factor/factor Xa activity, it inhibits factor VIIa/tissue factor/factor Xa-mediated signaling through protease-activated receptors (PARs) poorly compared to mammalian cell surface expressed TFPIα (102). In endothelial cells induced to produce tissue factor, the GPI-anchored TFPI serves to redistribute factor VIIa/tissue factor to caveolae in a factor Xa-dependent manner (97, 99). GPI-anchorage, however, may not be a requirement for factor VIIa/tissue factor inhibition by cell surface TFPIα as chimeric forms of rTFPI anchored by a GPI-anchor or a transmembrane domain produce equivalent levels of factor VIIa/tissue factor inhibition (103).

Whether TFPI is attached to the surface of other TFPI expressing cells (e.g. vascular smooth muscle cells, monocytes) in the same manner as in endothelial cells remains to be determined. Studies of the rTFPIβ isoform of TFPI in transfected cells demonstrates that it possesses an intrinsic GPI anchor (26, 29, 30), but direct evidence for the production of the TFPIβ protein by endothelial cells is currently lacking, despite the presence of TFPIβ mRNA in these cells.

5.3.2. Releasable TFPI

Heparin, thrombin, and shear increase the expression and release of TFPI from cells in culture (26, 29, 104–108). The release of TFPI induced acutely by these agonists appears to involve the redistribution of TFPI from stores located near the plasma membrane (perhaps caveolae) to the cell surface with the subsequent release into the media of a portion of the total cellular TFPI. During this process, the TFPI available at the surface of the cells remains unchanged or increases.

The parenteral administration of heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin, but not the heparin pentasaccharide (fondaparinux), rapidly increases the circulating levels of total TFPI in plasma 1.5–3 fold (Figure 6) (62, 109–111). Repeated doses of unfractionated heparin, but not low-molecular-weight heparin, exhaust the TFPI release-response (112–114). The form of TFPI that is released appears to be full-length TFPIα (28) and its source is presumed to be the endothelium.

The in vitro experiments discussed above show that: 1) Heparin treatment alone releases only a small fraction of cellular TFPI; 2) PIPLC treatment alone releases ~80% of cell surface TFPI and the remainder is released by subsequent heparin treatment; and 3) prior PIPLC treatment dramatically increases the amount of TFPI released by heparin (26, 29, 100). The mechanism(s) underlying these phenomena has not been elucidated, but appears to be more complicated than simply the “stripping” of TFPI from proteoglycan binding sites on the surface of the endothelium.

6. REGULATION OF COAGULATION

TFPI limits coagulation through both the inhibition of factor Xa, a process recently shown to be enhanced by protein S, and factor Xa-dependent feedback inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor. These properties of TFPI led to a reformulation of the coagulation cascade (19, 20, 115, 116) in which factor VIIa/tissue factor activation of factor IX and factor X is responsible for the initiation of coagulation, but subsequent amplification of the clotting process through the action of the factor IXa/factor VIIIa complex, a much more potent activator of factor X than factor VIIa/tissue factor (117), is required for hemostasis. The TFPI-mediated inhibition of factor Xa generation by factor VIIa/tissue factor, the inability to rapidly generate additional factor Xa through the action of factor IXa/factor VIIIa to overcome TFPI-mediated factor Xa inhibition, and the consequent dramatic reduction in thrombin generation helps explain the bleeding seen in individuals with hemophilia.

6.1. Factor Xa Inhibition

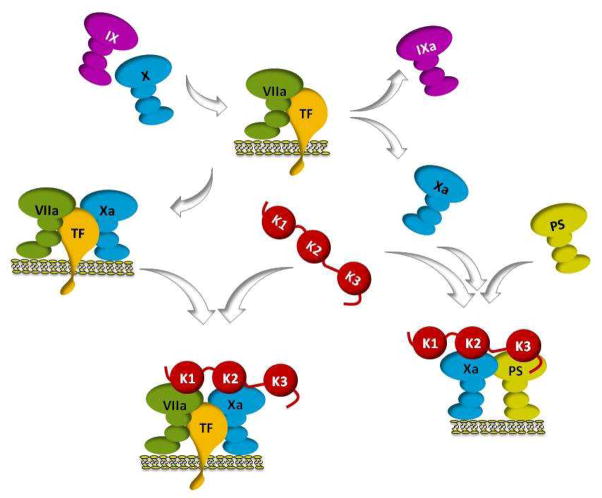

The Kunitz-2 domain of TFPI is responsible for the direct inhibition of factor Xa (19, 40) (Figure 8). The factor Xa-TFPI complex can form in the absence of calcium ions and is reversed by treatment with sodium dodecyl sulfate or high concentrations of the serine protease inhibitor benzamidine, which binds to the active site of factor Xa (19, 118). Other parts of the TFPI molecule besides the Kunitz-2 domain, however, are involved in its interaction with factor Xa. The carboxyterminal domain of TFPIα is required for rapid, efficient factor Xa inhibition (25, 41, 119–123) and cleavage of TFPI between Kunitz domains 1 and 2 (e.g. produced by neutrophil elastase) dramatically reduces the ability of TFPI to inhibit factor Xa (69). The inhibition of factor Xa by TFPI in the presence of physiologic calcium ion concentrations is enhanced by procoagulant phospholipids (122). The basic carboxyterminal region of the TFPIα molecule is important for this effect (119, 120) and presumably permits the simultaneous interaction of factor Xa and TFPIα with the phospholipid surface. Although the TFPIβ isoform lacks the carboxyterminus of TFPIα, its relatively slow inhibition of factor Xa in soluble phase (25) might be significantly enhanced when it is bound to phospholipid surfaces via its GPI-anchor (124).

Figure 8. Functions of TFPI.

The factor VIIa/tissue factor (TF) catalytic complex on a phospholipid surface activates factor X and factor IX (top). TFPI (center) binds to the transient tertiary factor VIIa/tissue factor/factor Xa complex (left) produced during the activation of factor X, forming a quaternary factor VIIa/tissue factor/factor Xa/TFPI inhibitory complex (bottom) in which the Kunitz-1 and Kunitz-2 domains of TFPI bind and inhibit factor VIIa and factor Xa, respectively. On the right, factor Xa, protein S and TFPI are shown forming an inhibitory complex at a phospholipid surface in which the Kunitz-2 domain binds and inhibits factor Xa and the Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminal domains of TFPIα are required for the interaction with protein S. Direct inhibition of factor Xa by TFPI and an alternative two-step pathway for factor VIIa/tissue factor inhibition in which a factor Xa/TFPI complex binds to factor VIIa/tissue factor producing the final quaternary inhibitory complex are not shown. Also not depicted are the factor VIIa/tissue factor and factor Xa inhibition produced by cell membrane-bound forms of TFPI. The Kunitz-1, Kunitz-2 and Kunitz-3 domains of TFPI are labeled K1, K2 and K3, respectively.

Protein S enhances the inhibition of factor Xa by TFPIα in the presence of phospholipids and calcium ions by increasing the affinity of the initial encounter complex between factor Xa and TFPIα 10-fold, to near the concentration of full-length TFPIα in plasma (125). This effect requires the Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminal domains of TFPIα, is reduced by a mutation at the P1 site of the Kunitz-3 (R199L) in TFPIα, and appears to involve at least in part a direct interaction of protein S with the Kunitz-3 domain (81, 125). The TFPIα structures required for the protein S-dependent enhancement of factor Xa inhibition mimic those required for TFPIα binding at the surface of endothelial cells, suggesting that protein S, which is also expressed by endothelial cells, may be involved in that interaction as well. As protein S binds factor Xa in a calcium ion and phospholipid-dependent fashion (126), the most straightforward explanation for the potentiating effect of protein S on factor Xa inhibition by TFPIα is that an association between protein S and TFPIα serves to increase TFPIα’s interactions with phospholipids and with factor Xa at phospholipid surfaces.

In mixtures containing prothrombin, factor Xa, factor V, phospholipids and calcium ions, TFPIα, with or without protein S, dramatically delays the initiation and reduces the ultimate rate of thrombin generation (81, 122, 127). In contrast, in similar mixtures containing factor Va, TFPIα ± protein S inhibits factor Xa activity only in the absence of prothrombin. Therefore the anti-factor Xa action of TFPIα must precede the activation of factor V and the formation of the prothrombinase complex or occur at sites where prothrombin has been consumed.

Heparin and other polyanions accelerate TFPI-mediated inhibition of factor Xa (120). The heparin dose-response for this effect exhibits an optimum, which suggests that the polyanion forms a template to which factor Xa and TFPI simultaneously bind (120, 122). Basic residues within the Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminal domains of TFPI are required for optimal heparin binding, and progressive carboxyterminal truncation of the TFPI molecule produces proteins with decreasing affinity for heparin (120, 128). Rather than a specific binding epitope, charge density on the glycosaminoglycan appears to be most important for TFPI binding (129).

6.2. Factor VIIa/Tissue Factor Inhibition

Factor Xa-dependent inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor requires the Kunitz-1 domain of TFPI and involves the formation of a quaternary factor Xa-TFPI-factor VIIa/tissue factor complex (Figure 8) (19, 20). The final quaternary complex could be produced in a two-step process in which TFPI first binds factor Xa and then the factor Xa-TFPI complex binds and inhibits factor VIIa/tissue factor. That this two-step pathway can occur has been documented in vitro. Kinetic studies, however, strongly suggest an alternative pathway in which TFPI interacts with the tertiary complex of factor VIIa/tissue factor/factor Xa, which forms transiently during the activation of factor X and from which the product factor Xa dissociates relatively slowly (130). As a result, factor VIIa/tissue factor inhibition is extremely rapid and the concentration of active factor Xa that escapes regulation depends linearly on the quantity of available of tissue factor. The fact that protein S substantially enhances the formation of the factor Xa-TFPI complex, but does not increase the inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor by TFPI is consistent with this alternative pathway (131). The Gla domain of factor Xa and Lys165-Lys166 of tissue factor, which are structures required for the optimal recognition of factor X by factor VIIa/tissue factor, are also important for the inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor by factor Xa-TFPI (19, 132, 133). Studies of the effects of heparin on factor Xa-dependent factor VIIa/tissue factor inhibition by TFPI have produced conflicting results (123, 134).

Full-length TFPIα inhibits factor Xa much faster than carboxyterminal truncated forms (25, 41, 119, 120). In contrast, full-length and carboxyterminal truncated forms of TFPIα appear to inhibit factor X activation by factor VIIa/tissue factor at comparable rates (134–136). A detailed kinetic analysis of these reactions, however, has not been performed. The ultimate affinity of the quaternary inhibitory complex formed with full-length TFPI is greater than that of complexes formed with truncated TFPI as the latter inhibitory complexes dissociate more rapidly (135, 136).

The requirement of factor Xa for the inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor by TFPI is not absolute, and high concentrations of TFPI will inhibit factor VIIa/tissue factor in the absence of factor Xa (41, 137, 138). This factor Xa-independent inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor by TFPI, however, is of uncertain physiologic relevance.

6.3. Anticoagulant Activity

The exogenous addition of non-physiologic concentrations of TFPIα to plasma inhibits the coagulation induced by factor Xa, the X-coagulant protein from Russell’s viper venom, and tissue factor to a similar extent (119), implying that the anticoagulant activity of TFPIα in these one-stage assays is due to its inhibition of factor Xa. An optimal effect requires the presence of protein S and is dependent on the Kunitz-3 and carboxyterminal domains of TFPIα (81, 119).

In plasma containing physiologic concentrations of full-length TFPIα (~0.2 nM), a similar effect of protein S and TFPI on thrombin generation can be demonstrated, but only at low concentrations of tissue factor (<14 ρM) or factor Xa (250 ρM) (139). At higher concentrations of tissue factor, the rate and extent of factor Xa generation produced by factor IXa/factor VIIIa as well as factor VIIa/tissue factor is presumably sufficient to overwhelm the factor Xa inhibition mediated through TFPIα and protein S. When the coagulation response to higher concentrations of tissue factor is limited by activation of the protein C pathway [e.g. addition of activated protein C (APC) or thrombomodulin to plasma], the effect of protein S/TFPI inhibition of factor Xa is again apparent (139, 140). Indeed, the combination of the actions of APC and TFPIα, enhanced by their mutual cofactor protein S, serves to synergistically limit coagulation.

The effect of factor VIIa/tissue factor inhibition by TFPI on thrombin generation may be identifiable when low levels of tissue factor (1.5 ρM) are used to induce coagulation in plasma [figure 1 and table 1 in (141)]. In these experiments, the increase in peak thrombin generation produced by the addition of anti-TFPI antibodies to the plasma was considerably greater than that produced by the addition of anti-protein S antibodies. The difference in the response to anti-TFPI and anti-protein S antibodies could be due to the inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor by TFPI and/or the protein S-independent inhibition of factor Xa by TFPI. At higher concentrations of tissue factor, however, the inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor by TFPI is difficult to detect due to the rapid onset of the amplification phase of coagulation in which factor IXa/factor VIIIa are responsible for producing the vast majority of factor Xa.

While the full-length form of TFPIα is required for optimal factor Xa inhibition and the anticoagulant effect of TFPI in one stage coagulation assays (81, 119, 142) the factor VIIa/tissue factor inhibition produced by the carboxyterminal truncated forms of TFPI, present at ~10-fold higher concentrations than full-length TFPIα in plasma, is demonstrable in two stage assay systems (142, 143). Though it seems likely that the attachment of carboxyterminal truncated forms of TFPI to large lipoprotein particles in plasma could hinder the recognition of cellular factor VIIa/tissue factor, this has not been directly tested.

6.4. The Cell-Surface Reservoir of TFPI

The amount of TFPI circulating in plasma represents only a small fraction of the total TFPI that is readily available. Heparin treatment in vivo induces the release of full-length TFPIα, raising levels of total TFPI in plasma 1.5–3-fold (28, 62, 109, 110) and the level of full-length TFPIα >20-fold. PIPLC treatment, however, releases much more TFPIα than heparin treatment from endothelial cells in culture (5-fold) (26, 100) and from placental tissue (>10-fold) (Figure 6) (100). Therefore, the major repository of TFPI is the indirectly GPI-anchored TFPIα on the surface of the endothelium and potentially other cells.

Why the majority of TFPI in vivo should be sequestered on the endothelial surface is not clear. Although a myriad of agonists has been shown to induce tissue factor production by endothelial cells in cell culture, the detection of endothelial tissue factor expression in vivo has been technically difficult and controversial. In part this could be due to the likely low levels of tissue factor that endothelial cells may produce, the specificity and potency of anti-tissue factor antibodies, and the problem of differentiating tissue factor intrinsically produced by endothelial cells from tissue factor that endothelial cells may corral from other cells or circulating microparticles. Nevertheless, the apparent expression of tissue factor by vascular endothelium in vivo has been observed in a number of pathological states (144–155). Since the production of even low levels of tissue factor by the endothelium could be deleterious, the important function of endothelial cell-associated TFPI may be to control the procoagulant and cell signaling (102) actions mediated by tissue factor induced in endothelial cells regularly by less severe stimuli (156).

7. IN MICE

Similar to humans, mice use alternative mRNA splicing to produce isoforms of TFPI. Messages for mTFPIα and mTFPIβ are constructed in the same fashion as their human counterparts and recombinant mTFPIβ is GPI-anchored when expressed in CHO cells. An additional isoform called mTFPIγ, however, is present in the mouse, but not in humans nor apparently other species. For mTFPIγ an exon downstream of that used to produce mTFPIβ is inserted at the same splice acceptor site and encodes a different 18 amino acid carboxyterminus (157). Whether mTFPIγ protein is produced in the mouse is not clear.

In contrast to humans in whom TFPIα is the major protein form of TFPI generated, in the mouse TFPIβ predominates. mTFPIα is present in mouse embryos and in the placenta and platelets of adult mice, but mTFPIα is not detectable in the other tissues of the adult mouse despite the fact that mTFPIα mRNA levels greatly exceed those of mTFPIβ and mTFPIγ in the tissues (83, 157,158). The basis for this discrepancy between mTFPIα mRNA and protein expression is unknown. The form of mTFPI in mouse plasma is mTFPIβ (158), which circulates at a level that is >20-fold the level of TFPI in human plasma and is not perceptibly increased following heparin treatment [Broze, unpublished data]. A small quantity of mTFPIα, however, may be detectable in mouse plasma after heparin treatment (158).

The genetic manipulations used in the production of the initial TFPI gene-disrupted mice led to deletion of the exon encoding the Kunitz-1 domain of mTFPI. Due to alternative mRNA splicing, however, these TFPI knock-out mice continue to express a form of mTFPI lacking the Kunitz-1 domain at ~40% the normal level (159). The loss of the Kunitz-1 domain prevents factor VIIa/tissue factor inhibition and likely also substantially reduces the factor Xa inhibition produced by the altered mTFPIΔK1 protein (69). Other potential functions of the remainder of the mTFPIα molecule, however, may remain intact in mTFPIΔK1 (160–164). TFPIΔK1 knock-out mice die intrautero of intravascular coagulation and a consumptive coagulopathy (159) and can be rescued by concomitant factor VII (165) or tissue factor (166) deficiency, confirming the critical role TFPI plays in regulating factor VIIa/tissue factor activity.

Heterozygous mTFPIΔK1 deficiency does not produce an obvious phenotype, but dramatically increases the prothrombotic phenotype of mice with factor VLeiden or thrombomodulin deficiency (167, 168). In the murine apolipoprotein E (apoE) deficient model of atherosclerosis, heterozygous mTFPIΔK1 deficiency modestly increases the atherosclerotic burden in carotid and iliac arteries and reduces the Rose Bengal/laser light-induced occlusion time in atherosclerotic carotid arteries (169). Heterozygous mTFPIΔK1 deficiency also increases neointimal proliferation in the murine model of flow cessation-induced vascular remodeling (170). On the other hand, over expression of mTFPIα (the isoform only present in the platelets of adult mice) in vascular smooth muscle cells limits ferric chloride induced carotid artery occlusion (171), reduces the smooth muscle cell proliferation and pulmonary vascular remodeling induced by chronic hypoxia (172), and unexpectedly lowers plasma cholesterol levels and atherosclerotic plaque development in the apoE knock-out model of atherosclerosis (173).

Using a Cre-lox strategy, White and colleagues have shown that the deletion of mTFPIK1 in endothelial and hematopoietic cells reduces TFPI activity in plasma by 70% and increases ferric chloride-induced carotid artery thrombosis, but does not affect embryonic development (174). The results of bone marrow transplantation experiments suggest that the endothelium and bone marrow derived cells are responsible for ~50% and ~20% of the mTFPIβ circulating in mouse plasma, respectively. The source of the remaining TFPIβ in mouse plasma was not identified, but might be vascular smooth muscle cells or cardiomyocytes. Whether the demonstrated enhanced arterial thrombosis is due to simply a 70% reduction in plasma TFPI activity or to the tissue specific loss of TFPI activity in endothelial cells or hematopoietic cells cannot be discerned from these studies. The potential contribution of platelets, which are the major reservoir of mTFPIα in the mouse, might be of particular interest in this regard.

8. PERSPECTIVE

Since the rediscovery of TFPI, many of the mechanisms underlying its regulation of coagulation have been defined. That there is more to learn is exemplified by the only recently demonstrated co-factor role played by protein S in the inhibition of factor Xa by TFPI. Moreover, important questions concerning TFPI physiology remain: At what levels are TFPIβ and TFPIδ expressed in humans; do the TFPI isoforms perform specific functions at specific locations; what is the form of TFPI circulating with lipoproteins in plasma and what is the mechanism for this association; which enzyme(s) is responsible for the carboxyterminal truncation of the plasma forms of TFPI; what is the relevance of potential interactions between TFPI and factor V and protein S in plasma; how is TFPIα bound at cell surfaces and the identity of its apparent GPI-anchored co-receptor; and what are the important physiological functions of this large reservoir of cell surface TFPI. The potential roles of TFPI in innate immunity, angiogenesis, and cellular functions that are not addressed in this review clearly also deserve attention. Studies in mice have demonstrated beyond doubt the critical importance of the regulation of tissue factor-mediated coagulation by TFPI. The substantial differences in TFPI physiology between mice and humans, however, need to be carefully considered before translating results in mouse models to the human situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nina Lasky for her assistance in organizing the references.

References

- 1.Loeb L, Fleisher MS, Tuttle L. The interaction between blood serum and tissue extract in the coagulation of the blood: I. The combined action of serum and tissue extract on fluoride, hirudin, and peptone plasma; the effect of heating on the serum. J Biol Chem. 1922;51:461–483. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loeb L, Fleisher MS, Tuttle L. The interaction between blood serum and tissue extract in the coagulation of blood: II. A comparison between the effects of the stroma of erythrocytes and of tissue extracts, unheated and heated, on the coagulation of the blood, and on the mechanism of the interaction of these substances with blood serum. J Biol Chem. 1922;51:485–506. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas L. Studies on the intravascular thromboplastin effect of tissue suspensions in mice: II. A factor in normal rabbit serum which inhibits the thromboplastin effect of the sedimentable tissue component. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1947;81:26–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider CL. The active principle of placental toxin: thromboplastin; its inactivator in blood: antithromboplastin. Am J Physiol. 1947;149:123–129. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1947.149.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann FD, Hurn M. Inactivation of thromboplastin by serum. Fed Proc. 1949;8:105. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClaughry RI. The specificity of anti-thromboplastin activity. J Miss State Med Assoc. 1950;49:685. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanchantin GFWA. Identification of a thromboplastin inhibitor in serum and in plasma. J Clin Invest. 1953;32:381–389. doi: 10.1172/JCI102749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry CG. The degeneration of brain thromboplastin in the presence of normal serum. J Clin Pathol. 1957;10:342–345. doi: 10.1136/jcp.10.4.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermansky F, Vitek J. The role of proconvertin and Stuart factor in the inactivation of tissue thromboplastin by serum. Experientia. 1960;16:455–456. doi: 10.1007/BF02171149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjort PF. Intermediate reactions in the coagulation of blood with tissue thromboplastin. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1957;9(suppl 27):1–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson SD. Plasma high density lipoproteins inhibit the activation of coagulation factor X by factor VIIa and tissue factor. FEBS Lett. 1981;132:37–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl PE, Abildgaard U, Larsen ML, Tjensvoll L. Inhibition of activated coagulation factor VII by normal human plasma. Thromb Haemost. 1982;48:253–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrison SA, Jesty J. Tissue factor-dependent activation of tritium-labeled factor IX and factor X in human plasma. Blood. 1984;63:1338–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders NL, Bajaj SP, Zivelin A, Rapaport SI. Inhibition of tissue factor/factor VIIa activity in plasma requires factor X and an additional plasma component. Blood. 1985;66:204–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubbard AR, Jennings CA. Inhibition of tissue thromboplastin-mediated blood coagulation. Thromb Res. 1986;42:489–498. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(86)90212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broze GJ, Jr, Miletich JP. Characterization of the inhibition of tissue factor in serum. Blood. 1987;69:150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao LV, Rapaport SI. Studies of a mechanism inhibiting the initiation of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation. Blood. 1987;69:645–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hubbard AR, Jennings CA. Inhibition of the tissue factor-factor VII complex: involvement of factor Xa and lipoproteins. Thromb Res. 1987;46:527–537. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broze GJ, Jr, Warren LA, Novotny WF, Higuchi DA, Girard TL, Miletich JP. The lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor that inhibits the factor VII-tissue factor complex also inhibits factor Xa: insight into its possible mechanism of action. Blood. 1988;71:335–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broze GJ, Jr, Girard TJ, Novotny WF. Regulation of coagulation by a multivalent Kunitz-type inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7539–7546. doi: 10.1021/bi00485a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broze GJ, Jr, Miletich JP. Isolation of the tissue factor inhibitor produced by HepG2 hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:1886–1890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wun TC, Kretzmer KK, Girard TJ, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Cloning and characterization of a cDNA coding for the lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor shows that it consists of three tandem Kunitz-type inhibitory domains. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6001–6004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girard TJ, Eddy R, Wesselschmidt RL, MacPhail LA, Likert KM, Byers MG, Shows TB, Broze GJ., Jr Structure of the human lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor gene. Intron/exon gene organization and localization of the gene to chromosome 2. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5036–5041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Logt CP, Reitsma PH, Bertina RM. Intron-exon organization of the human gene coding for the lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor: the factor Xa dependent inhibitor of the extrinsic pathway of coagulation. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1571–1577. doi: 10.1021/bi00220a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang JY, Monroe DM, Oliver JA, Roberts HR. TFPIbeta, a second product from the mouse tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) gene. Thromb Haemost. 1999;81:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Piro O, Lu L, Broze GJ., Jr Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol anchorage of tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Circulation. 2003;108:623–627. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078642.45127.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Novotny WF, Girard TJ, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Purification and characterization of the lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor from human plasma. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18832–18837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novotny WF, Palmier M, Wun TC, Broze GJ, Jr, Miletich JP. Purification and properties of heparin-releasable lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor. Blood. 1991;78:394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piro O, Broze GJ., Jr Role for the Kunitz-3 domain of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-alpha in cell surface binding. Circulation. 2004;110:3567–3572. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000148778.76917.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piro O, Broze GJ., Jr Comparison of cell-surface TFPIalpha and beta. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2677–2683. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maroney SA, Cunningham AC, Ferrel J, Hu R, Haberichter S, Mansbach CM, Brodsky RA, Dietzen DJ, Mast AE. A GPI-anchored co-receptor for tissue factor pathway inhibitor controls its intracellular trafficking and cell surface expression. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1114–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lareau LF, Green RE, Bhatnagar RS, Brenner SE. The evolving roles of alternative splicing. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mori Y, Hamuro T, Nakashima T, Hamamoto T, Natsuka S, Hase S, Iwanaga S. Biochemical characterization of plasma-derived tissue factor pathway inhibitor: post-translational modification of free, full-length form with particular reference to the sugar chain. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:111–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colburn P, Buonassisi V. Identification of an endothelial cell product as an inhibitor of tissue factor activity. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1988;24:1133–1136. doi: 10.1007/BF02620816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warn-Cramer BJ, Maki SL, Rapaport SI. A sulfated rabbit endothelial cell glycoprotein that inhibits factor VIIa/tissue factor is functionally and immunologically identical to rabbit extrinsic pathway inhibitor (EPI) Thromb Res. 1991;61:515–527. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90159-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith PL, Skelton TP, Fiete D, Dharmesh SM, Beranek MC, MacPhail L, Broze GJ, Jr, Baenziger JU. The asparagine-linked oligosaccharides on tissue factor pathway inhibitor terminate with SO4–4GalNAc beta 1, 4GlcNAc beta 1,2 Mana alpha. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:19140–19146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Girard TJ, McCourt D, Novotny WF, MacPhail LA, Likert KM, Broze GJ., Jr Endogenous phosphorylation of the lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor at serine-2. Biochem J. 1990;270:621–625. doi: 10.1042/bj2700621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diaz-Collier JA, Palmier MO, Kretzmer KK, Bishop BF, Combs RG, Obukowicz MG, Frazier RB, Bild GS, Joy WD, Hill SR, Duffin KL, Gustafson ME, Junger KD, Grabner RW, Galluppi GR, Wun TC. Refold and characterization of recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor expressed in Escherichia coli. Thromb Haemost. 1994;71:339–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebhard W, Tschesche H, Fritz H. Biochemistry of aprotinin and aprotinin-like inhibitors. In: Barrett AJ, Salvesen G, editors. Protease Inhibitors. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1986. pp. 375–388. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Girard TJ, Warren LA, Novotny WF, Likert KM, Brown SG, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Functional significance of the Kunitz-type inhibitory domains of lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor. Nature. 1989;338:518–520. doi: 10.1038/338518a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petersen LC, Bjorn SE, Olsen OH, Nordfang O, Norris F, Norris K. Inhibitory properties of separate recombinant Kunitz-type-protease-inhibitor domains from tissue-factor-pathway inhibitor. Eur J Biochem. 1996;235:310–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0310f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berndt KD, Beunink J, Schroder W, Wuthrich K. Designed replacement of an internal hydration water molecule in BPTI: structural and functional implications of a glycine-to-serine mutation. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4564–4570. doi: 10.1021/bi00068a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petersen LC, Bjorn SE, Nordfang O. Effect of leukocyte proteinases on tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Thromb Haemost. 1992;67:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamamoto T, Kisiel W. Full-length human tissue factor pathway inhibitor inhibits human activated protein C in the presence of heparin. Thromb Res. 1995;80:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(95)00179-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bajaj MS, Kuppuswamy MN, Manepalli AN, Bajaj SP. Transcriptional expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor, thrombomodulin and von Willebrand factor in normal human tissues. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1047–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Werling RW, Zacharski LR, Kisiel W, Bajaj SP, Memoli VA, Rousseau SM. Distribution of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in normal and malignant human tissues. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69:366–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osterud B, Bajaj MS, Bajaj SP. Sites of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) and tissue factor expression under physiologic and pathologic conditions. On behalf of the Subcommittee on Tissue factor Pathway Inhibitor (TFPI) of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the ISTH. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:873–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamabe H, Osawa H, Inuma H, Kaizuka M, Tamura N, Tsunoda S, Fujita Y, Shirato K, Onodera K. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor production by human mesangial cells in culture. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caplice NM, Mueske CS, Kleppe LS, Peterson TE, Broze GJ, Jr, Simari RD. Expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in vascular smooth muscle cells and its regulation by growth factors. Circ Res. 1998;83:1264–1270. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.12.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pendurthi UR, Rao LV, Williams JT, Idell S. Regulation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor expression in smooth muscle cells. Blood. 1999;94:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bajaj MS, Steer S, Kuppuswamy MN, Kisiel W, Bajaj SP. Synthesis and expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor by serum-stimulated fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells and cardiac myocytes. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1663–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen P, Broussas M, Cornillet-Lefebvre P, Potron G. Coexpression of tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor by human monocytes purified by leukapheresis and elutriation. Response of nonadherent cells to lipopolysaccharide. Transfusion. 1999;39:975–982. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39090975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crawley J, Lupu F, Westmuckett AD, Severs NJ, Kakkar VV, Lupu C. Expression, localization, and activity of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in normal and atherosclerotic human vessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1362–1373. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kereveur A, Enjyoji K, Masuda K, Yutani C, Kato H. Production of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in cardiomyocytes and its upregulation by interleukin-1. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1314–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kothari H, Kaur G, Sahoo S, Idell S, Rao LV, Pendurthi U. Plasmin enhances cell surface tissue factor activity in mesothelial and endothelial cells. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:121–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dahm A, Van Hylckama Vlieg A, Bendz B, Rosendaal F, Bertina RM, Sandset PM. Low levels of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) increase the risk of venous thrombosis. Blood. 2003;101:4387–4392. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lesnik P, Vonica A, Guerin M, Moreau M, Chapman MJ. Anticoagulant activity of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in human plasma is preferentially associated with dense subspecies of LDL and HDL and with Lp(a) Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1066–1075. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.7.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sandset PM, Lund H, Norseth J, Abildgaard U, Ose L. Treatment with hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors in hypercholesterolemia induces changes in the components of the extrinsic coagulation system. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:138–145. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hansen JB, Huseby NE, Sandset PM, Svensson B, Lyngmo V, Nordoy A. Tissue-factor pathway inhibitor and lipoproteins. Evidence for association with and regulation by LDL in human plasma. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:223–229. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abumiya T, Nakamura S, Takenaka A, Takenaka O, Yoshikuni Y, Miyamoto S, Kimura T, Enjyoji K, Kato H. Response of plasma tissue factor pathway inhibitor to diet-induced hypercholesterolemia in crab-eating monkeys. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:483–488. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hansen JB, Huseby KR, Huseby NE, Sandset PM, Hanssen TA, Nordoy A. Effect of cholesterol lowering on intravascular pools of TFPI and its anticoagulant potential in type II hyperlipoproteinemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:879–885. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.7.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Novotny WF, Brown SG, Miletich JP, Rader DJ, Broze GJ., Jr Plasma antigen levels of the lipoprotein-associated coagulation inhibitor in patient samples. Blood. 1991;78:387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Broze GJ, Jr, Lange GW, Duffin KL, MacPhail L. Heterogeneity of plasma tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1994;5:551–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kokawa T, Abumiya T, Kimura T, Harada-Shiba M, Koh H, Tsushima M, Yamamoto A, Kato H. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor activity in human plasma. Measurement of lipoprotein-associated and free forms in hyperlipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:504–510. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abumiya T, Enjyoji K, Kokawa T, Kamikubo Y, Kato H. An anti-tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) monoclonal antibody recognized the third Kunitz domain (K3) of free-form TFPI but not lipoprotein-associated forms in plasma. J Biochem. 1995;118:178–182. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ohkura N, Enjyoji K, Kamikubo Y, Kato H. A novel degradation pathway of tissue factor pathway inhibitor: incorporation into fibrin clot and degradation by thrombin. Blood. 1997;90:1883–1892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li A, Wun TC. Proteolysis of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) by plasmin: effect on TFPI activity. Thromb Haemost. 1998;80:423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stalboerger PG, Panetta CJ, Simari RD, Caplice NM. Plasmin proteolysis of endothelial cell and vessel wall associated tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:923–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Higuchi DA, Wun TC, Likert KM, Broze GJ., Jr The effect of leukocyte elastase on tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Blood. 1992;79:1712–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salemink I, Franssen J, Willems GM, Hemker HC, Li A, Wun TC, Lindhout T. Factor Xa cleavage of tissue factor pathway inhibitor is associated with loss of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost. 1998;80:273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Belaaouaj AA, Li A, Wun TC, Welgus HG, Shapiro SD. Matrix metalloproteinases cleave tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Effects on coagulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27123–27128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yun TH, Cott JE, Tapping RI, Slauch JM, Morrissey JH. Proteolytic inactivation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor by bacterial omptins. Blood. 2009;113:1139–1148. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ott I, Malcouvier V, Schomig A, Neumann FJ. Proteolysis of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-1 by thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:279–281. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.103591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tang H, Ivanciu L, Popescu N, Peer G, Hack E, Lupu C, Taylor FB, Jr, Lupu F. Sepsis-induced coagulation in the baboon lung is associated with decreased tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1066–1077. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Massberg S, Grahl L, von Bruehl ML, Manukyan D, Pfeiler S, Goosmann C, Brinkmann V, Lorenz M, Bidzhekov K, Khandagale AB, Konrad I, Kennerknecht E, Reges K, Holdenrieder S, Braun S, Reinhardt C, Spannagl M, Preissner KT, Engelmann B. Reciprocal coupling of coagulation and innate immunity via neutrophil serine proteases. Nat Med. 2010;16:887–896. doi: 10.1038/nm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duckers C, Simioni P, Spiezia L, Radu C, Gavasso S, Rosing J, Castoldi E. Low plasma levels of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in patients with congenital factor V deficiency. Blood. 2008;112:3615–3623. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Castoldi E, Simioni P, Tormene D, Rosing J, Hackeng TM. Hereditary and acquired protein S deficiencies are associated with low TFPI levels in plasma. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;8:294–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dahm AE, Sandset PM, Rosendaal FR. The association between protein S levels and anticoagulant activity of tissue factor pathway inhibitor type 1. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:393–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dahm AE, Bezemer ID, Sandset PM, Rosendaal FR. Interaction between tissue factor pathway inhibitor and factor V levels on the risk of thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1130–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heeb MJ, Prashun D, Griffin JH, Bouma BN. Plasma protein S contains zinc essential for efficient activated protein C-independent anticoagulant activity and binding to factor Xa, but not for efficient binding to tissue factor pathway inhibitor. FASEB J. 2009;23:2244–2253. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-123174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ndonwi M, Tuley EA, Broze GJ., Jr The Kunitz-3 domain of TFPIα is required for protein S-dependent enhancement of factor Xa inhibition. Blood. 2010;116:1344–1351. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-246686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Novotny WF, Girard TJ, Miletich JP, Broze GJ., Jr Platelets secrete a coagulation inhibitor functionally and antigenically similar to the lipoprotein associated coagulation inhibitor. Blood. 1988;72:2020–2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maroney SA, Haberichter SL, Friese P, Collins ML, Ferrel JP, Dale GL, Mast AE. Active tissue factor pathway inhibitor is expressed on the surface of coated platelets. Blood. 2007;109:1931–1937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith SA, Mutch NJ, Baskar D, Rohloff P, Docampo R, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate modulates blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:903–908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507195103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Smith SA, Choi SH, Davis-Harrison R, Huyck J, Boettcher J, Rienstra CM, Morrissey JH. Polyphosphate exerts differential effects on blood clotting, depending on polymer size. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266791. epub, Aug. 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palmier MO, Hall LJ, Reisch CM, Baldwin MK, Wilson AG, Wun TC. Clearance of recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) in rabbits. Thromb Haemost. 1992;68:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Valentin S, Nordfang O, Bregengard C, Wildgoose P. Evidence that the C terminus of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) is essential for its in vitro and in vivo interaction with lipoproteins. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1993;47:713–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Warshawsky I, Broze GJ, Jr, Schwartz AL. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein mediates the cellular degradation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6664–6668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Warshawsky I, Bu G, Mast A, Saffitz JE, Broze GJ, Jr, Schwartz AL. The carboxyterminus of tissue factor pathway inhibitor is required for interacting with hepatoma cells in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1773–1781. doi: 10.1172/JCI117855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Narita M, Bu G, Olins GM, Higuchi DA, Herz J, Broze GJ, Jr, Schwartz AL. Two receptor systems are involved in the plasma clearance of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24800–24804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Warshawsky I, Herz J, Broze GJ, Jr, Schwartz AL. The low density lipoprotein receptor related protein can function independently from heparan sulfate proteoglycans in tissue factor pathway inhibitor endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25873–25879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.25873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Valentin S, Schousboe I. Factor Xa enhances the binding of tissue factor pathway inhibitor to acidic phospholipids. Thromb Haemost. 1996;75:796–800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kojima T, Katsumi A, Yamazaki T, Muramatsu T, Nagasaka T, Ohsumi K, Saito H. Human ryudocan from endothelium-like cells binds basic fibroblast growth factor, midkine, and tissue factor pathway inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5914–5920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mast AE, Higuchi DA, Huang ZF, Warshawsky I, Schwartz AL, Broze GJ., Jr Glypican-3 is a binding protein on the HepG2 cell surface for tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Biochem J. 1997;327:577–583. doi: 10.1042/bj3270577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hamik A, Setiadi H, Bu G, McEver RP, Morrissey JH. Down-regulation of monocyte tissue factor mediated by tissue factor pathway inhibitor and the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4962–4969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ho G, Narita M, Broze GJ, Jr, Schwartz AL. Recombinant full-length tissue factor pathway inhibitor fails to bind to the cell surface: implications for catabolism in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2000;95:1973–1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sevinsky JR, Rao LV, Ruf W. Ligand-induced protease receptor translocation into caveolae: a mechanism for regulating cell surface proteolysis of the tissue factor-dependent coagulation pathway. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:293–304. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lupu C, Goodwin CA, Westmuckett AD, Emeis JJ, Scully MF, Kakkar VV, Lupu F. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor in endothelial cells colocalizes with glycolipid microdomains/caveolae. Regulatory mechanism(s) of the anticoagulant properties of the endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2964–2974. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ott I, Miyagi Y, Miyazaki K, Heeb MJ, Mueller BM, Rao LV, Ruf W. Reversible regulation of tissue factor-induced coagulation by glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:874–882. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.3.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mast AE, Acharya N, Malecha MJ, Hall CL, Dietzen DJ. Characterization of the association of tissue factor pathway inhibitor with human placenta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:2099–2104. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000042456.84190.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lupu C, Hu X, Lupu F. Caveolin-1 enhances tissue factor pathway inhibitor exposure and function on the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22308–22317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ahamed J, Belting M, Ruf W. Regulation of tissue factor-induced signaling by endogenous and recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor 1. Blood. 2005;105:2384–2391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dietzen DJ, Jack GG, Page KL, Tetzloff TA, Hall CL, Mast AE. Localization of tissue factor pathway inhibitor to lipid rafts is not required for inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor activity. Thromb Haemost. 2003;89:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lupu C, Lupu F, Dennehy U, Kakkar VV, Scully MF. Thrombin induces the redistribution and acute release of tissue factor pathway inhibitor from specific granules within human endothelial cells in culture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:2055–2062. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.11.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lupu C, Poulsen E, Roquefeuil S, Westmuckett AD, Kakkar VV, Lupu F. Cellular effects of heparin on the production and release of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in human endothelial cells in culture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2251–2262. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.9.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hansen JB, Svensson B, Olsen R, Ezban M, Osterud B, Paulssen RH. Heparin induces synthesis and secretion of tissue factor pathway inhibitor from endothelial cells in vitro. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:937–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Grabowski EF, Zuckerman DB, Nemerson Y. The functional expression of tissue factor by fibroblasts and endothelial cells under flow conditions. Blood. 1993;81:3265–3270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Westmuckett AD, Lupu C, Roquefeuil S, Krausz T, Kakkar VV, Lupu F. Fluid flow induces upregulation of synthesis and release of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2474–2482. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sandset PM, Abildgaard U, Larsen ML. Heparin induces release of extrinsic coagulation pathway inhibitor (EPI) Thromb Res. 1988;50:803–813. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(88)90340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Naumnik B, Rydzewska-Rosolowska A, Mysliwiec M. Different Effects of Enoxaparin, Nadroparin, and Dalteparin on Plasma TFPI During Hemodialysis: A Prospective Crossover Randomized Study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2010 doi: 10.1177/1076029610376936. epub, Aug. 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Walenga JM, Jeske WP, Samama MM, Frapaise FX, Bick RL, Fareed J. Fondaparinux: a synthetic heparin pentasaccharide as a new antithrombotic agent. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;11:397–407. doi: 10.1517/13543784.11.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hansen JB, Sandset PM, Huseby KR, Huseby NE, Nordoy A. Depletion of intravascular pools of tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) during repeated or continuous intravenous infusion of heparin in man. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hansen JB, Sandset PM. Differential effects of low molecular weight heparin and unfractionated heparin on circulating levels of antithrombin and tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI): a possible mechanism for difference in therapeutic efficacy. Thromb Res. 1998;91:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(98)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bendz B, Hansen JB, Andersen TO, Ostergaard P, Sandset PM. Partial depletion of tissue factor pathway inhibitor during subcutaneous administration of unfractionated heparin, but not with two low molecular weight heparins. Br J Haematol. 1999;107:756–762. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gailani D, Broze GJ., Jr Factor XI activation in a revised model of blood coagulation. Science. 1991;253:909–912. doi: 10.1126/science.1652157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.van ’t Veer C, Mann KG. Regulation of tissue factor initiated thrombin generation by the stoichiometric inhibitors tissue factor pathway inhibitor, antithrombin-III, and heparin cofactor-II. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4367–4377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.McGee MP, Li LC. Functional difference between intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways. Kinetics of factor X activation on human monocytes and alveolar macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:8079–8085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Broze GJ, Jr, Warren LA, Girard JJ, Miletich JP. Isolation of the lipoprotein associated coagulation inhibitor produced by HepG2 (human hepatoma) cells using bovine factor Xa affinity chromatography. Thromb Res. 1987;48:253–259. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(87)90422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wesselschmidt R, Likert K, Girard T, Wun TC, Broze GJ., Jr Tissue factor pathway inhibitor: the carboxyterminus is required for optimal inhibition of factor Xa. Blood. 1992;79:2004–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wesselschmidt R, Likert K, Huang Z, MacPhail L, Broze GJ., Jr Structural requirements for tissue factor pathway inhibitor interactions with factor Xa and heparin. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1993;4:661–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lindhout T, Franssen J, Willems G. Kinetics of the inhibition of tissue factor-factor VIIa by tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:910–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Huang ZF, Wun TC, Broze GJ., Jr Kinetics of factor Xa inhibition by tissue factor pathway inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26950–26955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jesty J, Wun TC, Lorenz A. Kinetics of the inhibition of factor Xa and the tissue factor-factor VIIa complex by the tissue factor pathway inhibitor in the presence and absence of heparin. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12686–12694. doi: 10.1021/bi00208a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chen HH, Vicente CP, He L, Tollefsen DM, Wun TC. Fusion proteins comprising annexin V and Kunitz protease inhibitors are highly potent thrombogenic site-directed anticoagulants. Blood. 2005;105:3902–3909. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hackeng TM, Sere KM, Tans G, Rosing J. Protein S stimulates inhibition of the tissue factor pathway by tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3106–3111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504240103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yegneswaran S, Hackeng TM, Dawson PE, Griffin JH. The thrombin-sensitive region of protein S mediates phospholipid-dependent interaction with factor Xa. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33046–33052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806527200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]