Abstract

Background

Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs), composed of solid and liquid lipids, and surfactants are potentially good colloidal drug carriers. Thymoquinone is the main bioactive compound of Nigella sativa. In this study, the preparation, gastroprotective effects, and pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of thymoquinone (TQ)-loaded NLCs (TQNLCs) were evaluated.

Method

TQNLCs were prepared using hydrogenated palm oil (Softisan® 154), olive oil, and phosphatidylcholine for the lipid phase and sorbitol, polysorbate 80, thimerosal, and double distilled water for the liquid lipid material. A morphological assessment of TQNLCs was performed using various methods. Analysis of the ulcer index, hydrogen concentration, mucus content, and biochemical and histochemical studies confirmed that the loading of TQ into the NLCs significantly improved the gastroprotective activity of this natural compound against the formation of ethanol-induced ulcers. The safety of TQNLC was tested on WRL68 liver normal cells with cisplatin as a positive control.

Results

The average diameter of the TQNLCs was 75 ± 2.4 nm. The particles had negative zeta potential values of −31 ± 0.1 mV and a single melting peak of 55.85°C. Immunohistochemical methods revealed that TQNLCs inhibited the formation of ethanol-induced ulcers through the modulation of heat shock protein-70 (Hsp70). Acute hepatotoxic effects of the TQNLCs were not observed in rats or normal human liver cells (WRL-68). After validation, PK studies in rabbits showed that the PK properties of TQ were improved and indicated that the drug behaves linearly. The Tmax, Cmax, and elimination half-life of TQ were found to be 3.96 ± 0.19 hours, 4811.33 ± 55.52 ng/mL, and 4.4933 ± 0.015 hours, respectively, indicating that TQ is suitable for extravascular administration.

Conclusion

NLCs could be a promising vehicle for the oral delivery of TQ and improve its gastroprotective properties.

Keywords: lipid based nanoparticles, black seed oil, gastric ulcer

Introduction

Nigella sativa L. (Ranunculaceae) is widely used and cultivated throughout many tropical regions of the world. N. sativa seeds have been used as a traditional remedy for more than 4 centuries.1,2 These seeds are reported to benefit almost every system of the body. Experimental studies have confirmed that the plant is a respiratory stimulant and has diuretic, hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory,3,4 antioxidant, anticancer, and analgesic properties.5–8 Previous phytochemical analyses of N. sativa showed that the seed contains alkaloids, tannins, steroids, and flavonoids.2,9,10 The possible roles of N. sativa oil in gastric secretion and in ethanol-induced ulcer formation in rats have been previously reported. Both the oil and its bioactive compound, thymoquinone (TQ), were shown to protect the stomach during ischemia/reperfusion-, pylorus ligation- and alcohol-induced gastric mucosal injury in rats, through a radical-scavenging activity.7,11

Nanotechnology is a rapidly progressing field and is now being applied in the treatment of various human ailments.12 Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) have attracted academic and industrial attention in the last few years, and they have the potential to be used as alternative carriers for many pharmaceutical drugs.13,14 These lipid-based nanoparticles are usually formed by high-pressure homogenization, and this procedure can be customized to yield particle dispersions with up to 80% solid content.15,16 NLCs can usually be applied when solid nanoparticles do not improve the delivery of drugs. In the pharmaceutical industry, NLCs are used for the topical, oral and parenteral administration of drugs. They can also be used in cosmetics, food, and agricultural products. The oral administration of NLCs is an attractive and promising area of research.15,17 The usefulness of lipid particles for oral delivery was first demonstrated with lipid-based nanoformulated cyclosporine. NLCs have the potential of even better performance. In addition, lipids improve the pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of a variety of drugs, also supporting the use of lipid particles for oral delivery. Of special interest for oral delivery are lipid-drug conjugated nanoparticles that allow for a high loading capacity of hydrophilic drugs.18 The primary drugs of interest are compounds that undergo chemical degradation in the gastrointestinal tract. Examples of drugs that have been incorporated into lipid nanoparticles are timolol, deoxycorticosterone, doxorubicin, idarubicin, thymopentin, diazepam, gadolinium (III), progesterone, hydrocortisone, and paclitaxel.19,20 Because of their ability to solubilize water-insoluble drug molecules, lipid-based drug delivery systems have proven to enhance drug absorption and dissolution rates in the gastrointestinal tract.21 A previous study by Kumar et al22 showed an enhancement of the in vivo antiulcer effects of ranitidine-loaded microparticles. No study has reported the use of nanotechnological techniques to enhance the antiulcer properties of TQ. However, nanoparticles of this natural compound have been previously prepared using various agents, such as poly(lactide-co-glycolide), chitosan, and β-cyclodextrin8,23,24 for anti-inflammatory, anticancer, chemosensitization, and drug delivery studies.8 Therefore, the current study, the first of its kind, was designed to investigate the preparation, in vitro toxicity, and gastroprotective and PK properties of TQ-loaded NLCs (TQNLCs) in animal models.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Softisan® 154 (S154), or hydrogenated palm oil (HPO), was a gift from Sasol-Condea (Hamburg, Germany). Lipoid S100 (soy lecithin) was a gift from Lipoid GmbH (Ludwigshafen, Germany). Thimerosal, olive oil, sorbitol, ethanol, TQ, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), penicillin, streptomycin, periodic acid-Schiff stain (PAS), fetal bovine serum (FBS), acetonitrile, methanol, and tetrazolium bromide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Oleyl alcohol (a fatty alcohol, and nonionic surfactant or emulsifier), paraffin wax, potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate (KH2PO4), and formaldehyde were also purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Omeprazole and zerumbone were a generous gift from the Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Malaysia.

Preparation of nanostructured lipid carriers and loading of thymoquinone

The NLCs were prepared by a high-pressure homogenization technique.25 The HPO and olive oil were mixed with 1.7% (w/v) Lipoid S100 in a sealed beaker and heated to 10°C above the melting point of the solid lipid to prevent the lipid memory effect. Three different formulations of NLCs were used; these contained olive oil:HPO ratios of 1:9, 2:8, and 3:7 for NLC(10), NLC(20), and NLC(30), respectively. Three hundred milligrams of TQ were dissolved into the lipid phase. Sorbitol (4.75% [w/v]) and thimerosal (0.005 g) were dissolved in double-distilled water to form the aqueous phase. Polysorbate 80 (1% [v/v]) was chosen for NLC formulation and added into the binary mixtures. The effect of polysorbate 80 on the characteristics of NLC(20) was determined by varying the surfactant concentrations (0.5%, 1.0%, 2.0%, and 4.0% [v/v]) in the nanoparticle formulation.25 The lipid phase was dispersed into the aqueous phase with high-speed stirring using the Ultra Turrax® (IKA Works GmbH & Co, KG, Staufen, Germany) at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes to yield a hot pre-emulsion. The pre-emulsion was forced through a high-pressure homogenizer (EmulsiFlex C-50, Avestin Inc, Ottawa, ON, Canada) at 1000 bar for 20 cycles according to the protocol developed in our laboratory.25 The suspension was allowed to stand at room temperature to recrystallize and form the NLCs. The particle size, morphology, electrostatic-charge, homogeneity, and crystallinity of the NLCs were characterized.

Particle size

The average particle diameter and polydispersity index of the NLC dispersions were determined by dynamic light scattering in a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) equipped with noninvasive back-scattering technology. Five independent measurements were obtained at 25°C and a 173 angle with respect to the incidence light. The particle specific surface area (Aspec) of the nanoparticle was calculated according to the following formula:

| (1) |

where ρ = density and r = radius of the particle.

Zeta potential

Laser Doppler velocimetry and the phase analysis light scattering (M3-PALS) technique were used for the measurement of the zeta potential in our study. The Zetasizer Nano ZS (helium-neon [He-Ne] laser at a power = 4 mW and lambda = 633 nm) was used to determine the surface charge and to predict the long-term stability of the NLCs. The pH of each sample was adjusted to 7.4 prior to analysis. Five measurements were made on each sample.

Crystallinity

Thermal analysis of the selected TQNLCs was performed using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) using the Mettler DSC 822e (Mettler Toledo) within 7 days after the TQNLC preparation. Briefly, 5 mL of the TQNLC dispersion was freeze dried (Alpha 1–2/LD Plus; Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH, Osterode am Harz, Germany) based on the protocol developed in our laboratory.25 Ten milligrams of dried NLC was weighed on an aluminum pan. An empty aluminum crucible was used as a reference. The system was calibrated with an indium standard. A nitrogen purge gas was used to provide an inert gas atmosphere within the DSC cell, at a flow rate of 60 cm3/min. The thermal profile of the NLC was recorded at temperatures ranging from 25°C to 70°C, with a heating rate of 5°C/min. The crystallinity index (CI) of the NLC was calculated from the enthalpy of fusion using the following formula:25

| (2) |

An in vitro comparative cytotoxicity study was conducted between TQ and the TQNLCs, namely TQNLC(20), using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay in normal human hepatic cells (WRL-68; American Type Cell Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA, USA). This assay is based on the conversion of yellow tetrazolium bromide to a purple formazan derivative by mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase in viable cells. WRL-68 cells were incubated in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 saturation and were maintained in DMEM. The medium was supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin. For the measurement of cell viability, the cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells/mL in a 96-well plate and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cells were treated with the study compounds and incubated for 24 hours. After 24 hours, an MTT solution, at 2 mg/mL, was added for 1 hour. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a Tecan plate reader (Sunrise™ model, Tecan Group Ltd, Männedorf, Switzerland). The results were expressed as the percentage of viable cells relative to the control, after 24 hours of exposure to the test agent. The potency of cell growth inhibition for both compounds was expressed as the concentration that caused a 50% loss of cell growth (IC50). Viability was defined as the ratio (expressed as a percentage) of the absorbance of treated cells to untreated cells. The concentration of the TQNLCs was calculated based on the amount of TQ. The safety of TQNLC was tested on WRL68 liver normal cells with cisplatin as a positive control.

Gastroprotective studies

Animal husbandry and caging

Sprague Dawley® male rats (220 ± 20 g) were procured from the Experimental Animal House, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Malaysia. To avoid coprophagy, the rats were kept individually in cages, with raised floors of wide mesh. Food and water were provided throughout the experiment ad libitum. All animals received human care according to the criteria outlined in the “Guide for the Care and use of Laboratory Animals” prepared by the Experimental Animal House, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Malaysia. Ethical clearance for this study was obtained by the Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya (Ethic No: PM 07/05/2008 MAA [a][R]).

Ethanol-induced gastric ulcer

Ulcers were induced in the rats, using ethanol.11 The rats were fasted for 48 hours prior to oral dosing and were divided randomly into four treatment groups and two control groups (n = 6). One hour before intragastric administration of ethanol (5 mL/kg), the rats were orally treated as follows: group 1 was not treated; group 2 was treated with only the nonloaded vehicle (5% polysorbate 80 [v/v]) (5 mL/kg [body weight]); group 3 was treated with omeprazole (20 mg/kg); groups 4 and 5 were treated with TQNLC20 (30 and 60 mg/kg, respectively); and group 6 was treated with TQ (60 mg/kg). One hour after ethanol dosing, all animals were sacrificed under anesthesia (ketamine and xylazine), and their blood was collected.26 Groups 1 and 6 served as the controls.

Measurement of gastric juice acidity, mucus content and biochemical parameters

The gastric juice of each animal was collected and centrifuged to measure the hydrogen ion concentration (pH), of the supernatant, using a pH-meter (ARGENTHAL™ model, Mettler Toledo). The weight of the gastric mucosa from the sedimentation was obtained using a precise balance (Mettler Toledo). Animal blood samples were analyzed at the University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur to evaluate changes in hepatic biomarkers.27

Macroscopic assessment

Gastric ulcer appearance was measured using a planimeter (10 × 10 mm2 = ulcer area), under a dissecting microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood NY, USA) (1.8×). The area of each lesion was measured by counting the number of small squares (2 mm × 2 mm) covering the length and width of each ulcer band. The sum of the areas of all of the lesions for each stomach was used in the calculation of the ulcer area (UA), which took into account the sum of the small squares (4 mm2 × 1.8 magnification = UA mm2). The inhibition percentage (I%) was calculated with slight in-house modifications to the following formula that was previously described.28

| (3) |

Microscopic evaluation using hematoxylin and eosin, PAS, and immunohistochemistry

For histopathological evaluation, a small fragment of the gastric ulcer from each animal was fixed with a 10% buffered formalin solution. Formalin-fixed tissues were dehydrated with alcohol and xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax. Tissue sections of 5 μm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for light microscopy29 and with PAS30 for the evaluation of mucus production, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma Aldrich). A primary antibody for heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Dallas, TX, USA) (dilution 1:500) was used to investigate the mechanism of TQNLC20 as a potential antiulcer agent. Immunohistochemical detection for these antibodies was performed (ARK™ [Animal Research Kit] Peroxidase; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark).

Pharmacokinetic studies

Animals

Three New Zealand White rabbits weighing 2.3–2.6 kg (Chenur Supplier BDH, Serdang, Malaysia) were housed in unidirectional airflow rooms under controlled temperature (22°C ± 2°C) and humidity (50% ± 10%), with 12 hour light/ dark cycles. Filtered tap water was available ad libitum to all animals. TQNLC(20) was dosed extravascularly (intraperitoneally [IP]), at 10 mg/kg body weight for the three rabbits.

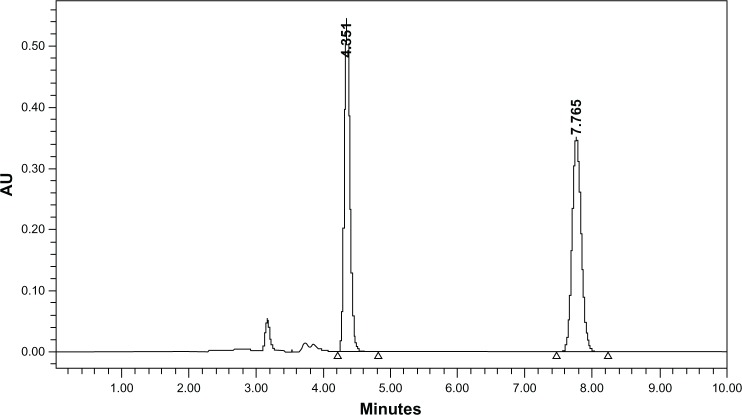

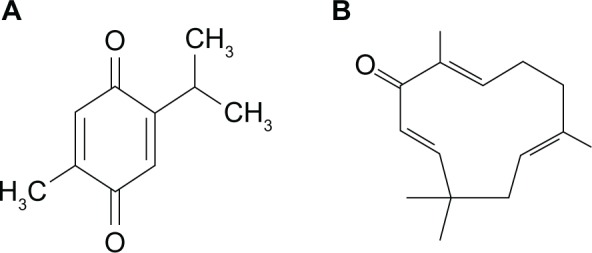

High performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) analysis

Liquid chromatography was performed with an Alliance HPLC system (Waters Corp, Milford MA, USA) with an autosampler, at 4°C. The structures of TQ and the internal standard (IS), zerumbone are shown in Figure 1A. The extraction of TQ and the IS from rabbit plasma was performed using diethyl ether as an extraction solvent. The separation was conducted on a symmetry C18 column (250 mm × 0.46 mm ID, 5 μm; Waters Corp), at ambient temperature. The analysis was achieved with a mobile phase consisting of 45:40:15 acetonitrile:methanol:0.01M potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate buffer, delivered at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/ min. The injection volume was 20 μL, and the running time was 240 minutes. TQ and the IS were detected at concentrations of 10 and 20 ng/mL, respectively. The validation parameters measured were specificity, linearity, accuracy, precision, stability, and robustness. The method was validated according to US Food and Drug Administration guidelines. Specificity was obtained by comparing the chromatograms of six different batches of blank plasma obtained from six different subjects and plasma samples injected with the IS and TQ. The calibration curves were constructed by a weighted (1/x) least–square linear regression method. The lower limit of quantification (LOQ) was the lowest concentration of the analyte that could be determined with acceptable precision and accuracy. Three replicates of each concentration were processed as described in the sample preparation section, on days 1, 2, 3, and 15 to determine intraday and interday precision and accuracy. The intraday and interday accuracy (RE%) values were calculated using established equations.31

Figure 1.

The structure of (A) thymoquinone and (B) zerumbone (IS).

Abbreviation: IS, internal standard.

Analysis of PK parameters

Pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters were estimated using a noncompartmental model. Area under the concentration-time curve from zero to infinity (AUC0-∞) was obtained for each TQNLC concentration by a log-linear trapezoid method, and the t1/2 (lambda Z) was determined based on the four terminal concentration time points (WinNonlin® 6.1 software; Pharsight, St Louis, MO, USA). The PK analysis was conducted using the mean plasma concentration versus time data. All experimental data points were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The corresponding mean PK parameters (±SD) were calculated from individual estimates in the animal group. Significant differences between the experiments were calculated using a Student’s t-test (unpaired) (SigmaPlot®, RockWare Inc, Golden, CO, USA), using a two-tailed distribution and a two-sample unequal variance (heteroscedastic) method. A value of P < 0.05 was adopted to indicate statistical significance.

Statistical analysis

Data from the individual experiments are expressed as the mean ± SD. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by Duncan’s multiple range tests or the Student’s t-test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Physiochemical properties of the thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (TQNLCs)

The current study was undertaken to investigate the gastroprotective and PK properties of TQNLCs in animal models. TQNLCs were prepared using lipid phase and liquid lipid material. Physiochemical properties assessment of the TQNLCs was performed using various methods. The specific surface area for the TQNLC(20) was 49.07 ± 0.32 m2/g. The minimum endothermic peak and enthalpy for HPO were 62.3°C and 173.73 J g−1, respectively and for NLC were 56.7°C and 47.23 J g−1 respectively. The melting point of the NLC was 4.3 °C lower than that of HPO, while the CI was 28.02% of the solid lipid. The average diameter of TQNLC(20) was 75 ± 2.5 nm. The particles had negative zeta potential values of −31 ± 0.1 mV The prepared TQNLC20 appeared to have a single melting peak of 55.85°C. The physicochemical properties of the NLCs were affected by the type of surfactant utilized.32,33 Our previous studies revealed that polysorbate 80 is an excellent surfactant for dispersing hydrogenated palm oil, in terms of particle size, charges, and crystallizing behavior. The type of stabilizer is known to significantly affect the average size and charge but not the size distribution of NLCs.25,34 We have previously reported that NLC20 is small and would have a superior particle surface-to-volume ratio and an improved bioavailability and drug-loading efficiency relative to NLC30.25 Therefore, we used NLC(20)-loaded thymoquinone (TQNLC[20]) for further biological analysis. NLCs possess exclusive characteristics that can improve the performance of a variety of loaded drug forms.35,36 Lipids improve the PK properties of a variety of drugs, thus supporting the use of lipid particles for oral delivery. Of special interest for oral delivery, are the lipid-drug conjugate nanoparticles, which allow for the high loading capacity of hydrophilic drugs. The primary drugs of interest are the compounds that undergo chemical degradation in the gastrointestinal tract.23,36

Gastroprotective study

It was reported previously that the gastric mucosa is a main and the first line of defense, protecting the stomach from external and internal necrotizing agents.37 Ethanol administration causes dissipation of the mucosal layer, leading to acid diffusion and lesion formation.38 Endogenous protective mechanisms protect the gastric mucosa against various agents by binding to free radicals, such as those resulting from the action of ethanol, and by regulating the production and nature of mucus.39

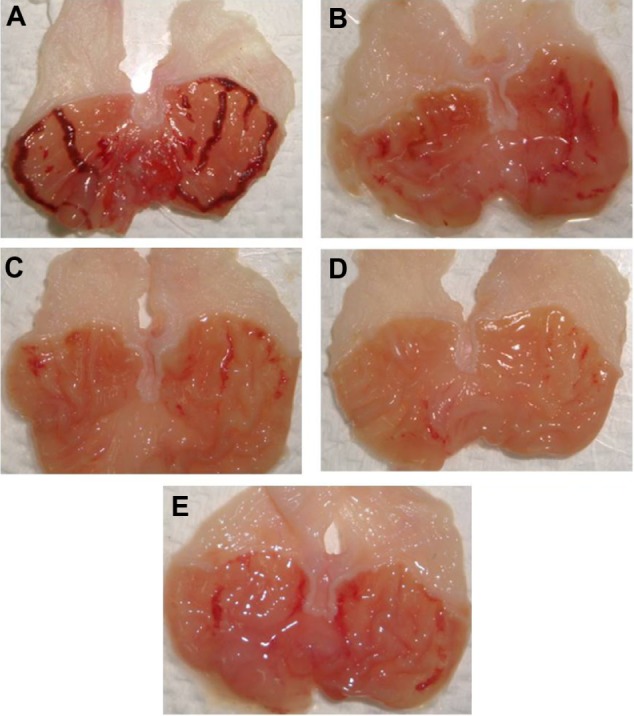

As mentioned previously, this study was designed to investigate the role of NLCs in improving the protective properties of TQ against ethanol-induced stomach ulceration. Pretreatment with TQNLC(20) considerably reduced the area of the ulcer formed relative to the control ulcer group (Table 1). As shown in Table 1 and Figure 2, TQNLCs, at a dose of 60 mg/kg body weight, produced significantly higher ulcer inhibition (97.6%) (P < 0.05) compared with the nonloaded NLCs (89.1%) administered at the same dose. Animals pretreated with NLC(20) (Group 6) were not protected against ethanol-induced injury. It was also observed that TQNLC(20) modulated the mucus content and pH of the gastric contents of animals in Groups 3 and 4 relative to the ethanol-induced group (Table 1). Moreover, histological evaluation demonstrated that TQNLC(20) was a better protector against ethanol-induced ulcers, as is indicated by the absence of edema and leukocyte infiltration shown in Figure 3. Treatment of the animals with TQNLC(20) (60 mg/kg) resulted in the expansion of a substantial continuous PAS-positive mucous layer.

Table 1.

Protective effect of TQNLC(20) and thymoquinone on ethanol-induced ulceration

| Animal group | Pretreatment 5 mL/Kg | pH | Mucus | UA | I% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ulcer control group | 3.74 ± 0.4a | 2.94 ± 0.4a | 954.3 ± 4.5a | |

| 2 | Omeprazole | 6.43 ± 0.2b | 1.78 ± 0.1b | 183 ± 5.8b | 80.8 |

| 3 | TQNLC (30 mg/Kg) | 6.01 ± 0.1b | 3.07 ± 0.1a | 47 ± 2.4c | 95.1 |

| 4 | TQNLC (60 mg/Kg) | 6.95 ± 0.4c | 3.96 ± 0.3c | 23 ± 2.1d | 97.6 |

| 5 | Thymoquinone (60 mg/Kg) | 6.5 ± 0.3c | 3.24 ± 0.4d | 112.4 ± 3.2e | 89.1 |

| 6 | NLC20 (60 mg/Kg) | 3.74 ± 0.4a | 2.87 ± 0.2a | 921.1 ± 45.3a | 3.34 |

Abbreviations: I%, inhibition percentage; NLC, nanostructured lipid carriers; TQNLC, thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers; UA, ulcer area.

Figure 2.

Gross evaluation of the stomachs from various animal groups. Results showed that rats pretreated orally with (C and D) TQNLC(20) at the doses of 30 and 60 mg/kg, respectively and with (B) omeprazole at 20 mg/kg had considerably reduced areas of gastric ulcer formation compared with (A) rats pretreated with only polysorbate 80 (the ulcer control group). (F) effect of NLC(20) (60 mg/kg) on the ethanol-induced ulcers.

Note: Magnification 1.8×.

Abbreviation: TQNLC, thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers.

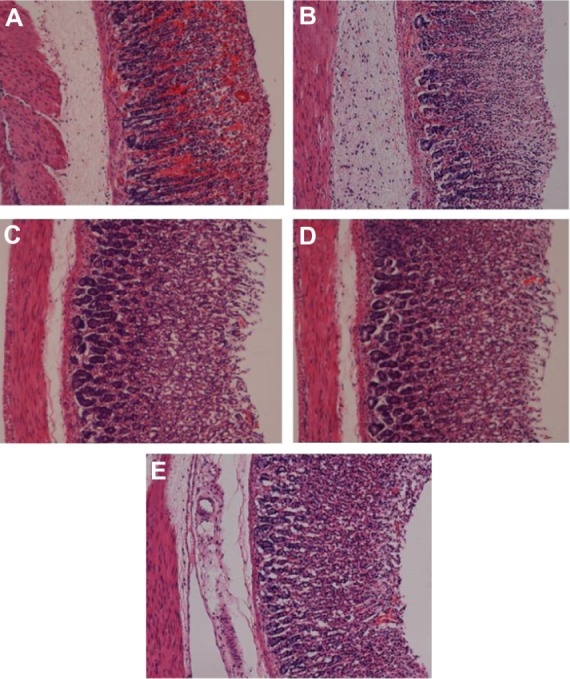

Figure 3.

Histopathological evaluations. Results showed that oral dosage of (C and D) TQNLC(20) at the doses of 30 and 60 mg/kg, respectively and with (B) omeprazole at the dose of 20 mg/kg improved the histopathology of rats’ stomach compared with (A) the rats pretreated with only polysorbate 80 (ulcer control group).

Notes: Hematoxylin and eosin stain; Magnification 10×.

Abbreviation: TQNLC, thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers.

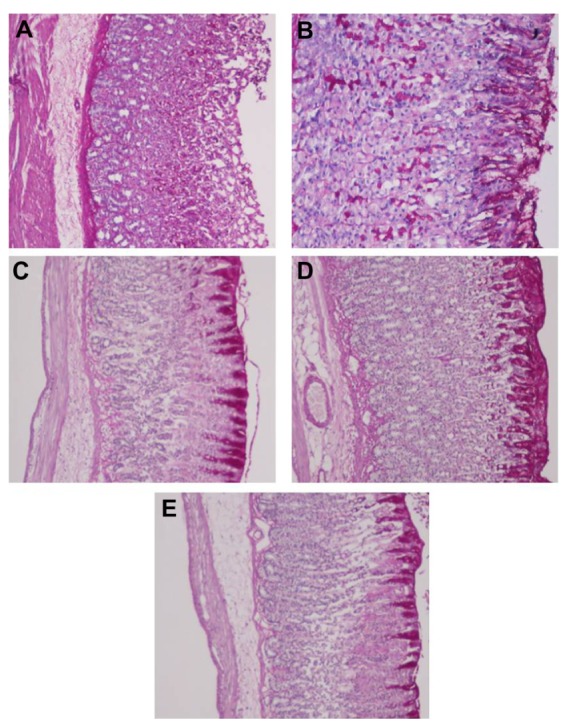

This was evidenced by the accumulation of a bright purple color, as shown in Figure 4. Additionally, immunohistochemical staining showed that TQNLC(20) was able to modulate the expression of Hsp70, as shown in Figure 5. A previous study by Kumar et al22 showed an enhancement in the in vivo antiulcer properties of ranitidine-loaded microparticles. Clarithromycin- and omeprazole-containing gliadin nanoparticles, for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori, were also developed, and they were shown to be effective against H. pylori–triggered gastric ulcers.40 Moreover, Raffin et al17 showed that the in vivo antiulcer properties of pantoprazole could be improved by loading the drug into microparticles.7 Various other nanoparticles have been prepared; poly (lactide-co-glycolide), chitosan, β-cyclodextrin, and acrylated vegetable oil were used to improve the effectiveness and bioavailability of TQ.8,41,42

Figure 4.

PAS staining for the evaluation of mucus production. Results showed that rats pretreated orally with (C and D) TQNLC(20) at the doses of 30 and 60 mg/kg, respectively and with (B) omeprazole at the dose of 20 mg/kg showed more PAS-positive mucus as compared with (A) the rats pretreated with only polysorbate 80 (ulcer control group).

Note: Magnification 10×.

Abbreviations: PAS, periodic acid-Schiff base; TQNLC, thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers.

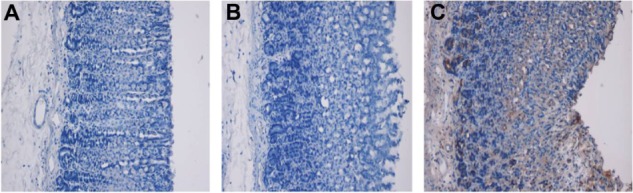

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of ulcer lesions using Hsp70 primary antibody and an ARK™ Animal Research Kit (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). (A) Gastric tissues from normal animals; (B) Gastric tissues from ethanol-induced ulcer animals; (C) Gastric tissues from TQNLC(20)-pretreated (60 mg/kg) animals.

Note: Magnification 10×.

Abbreviations: Hsp, heat shock protein; TQNLC, thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers.

In vitro cytotoxicity

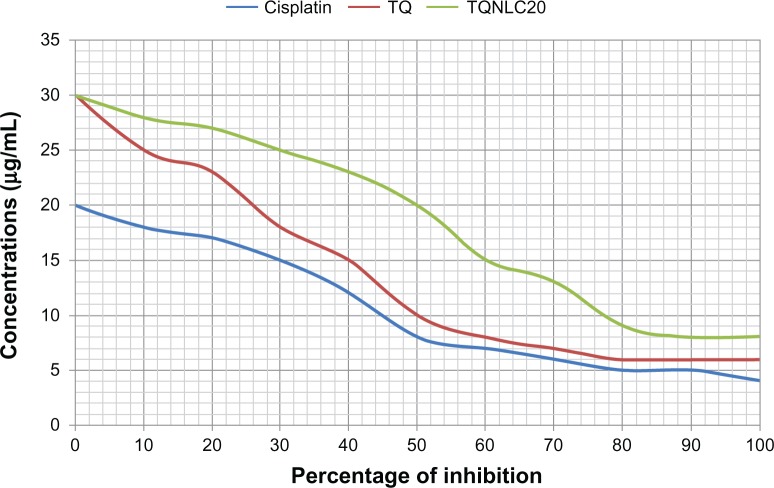

The safety of nanocarriers is a big concern to drug developers and end users.43 Therefore, we assessed the acute hepatotoxic effects of TQNLC(20) in rats and in normal human liver cells. Serum analysis of liver biomarkers showed that the rats that underwent ethanol-induced ulceration had increased levels of liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase) compared with the normal and TQNLC(20)-treated group (data are not shown). The current study also revealed that loading of TQ into NLC(20) decreased the cytotoxicity of this compound in normal liver cells (WRL-68). As shown in Figure 6, the IC50 of TQNLC(20) in WRL-68 cells was 20.1 ± 0.9 μg/mL, which was significantly higher than that of nonloaded TQ (10.5 ± 0.37 μg/mL). Our previous results showed that NLCs were safe in BALB/c 3T3 cells in vitro.34 In this study, cisplatin (Sigma Aldrich), a known cytotoxic agent, was used as a positive control (5.1 ± 0.28 μg/mL) and to exclude human experimental error in MTT assay.

Figure 6.

MTT cell viability assay on normal human hepatic cells (WRL-68).

Abbreviations: MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; TQ, thymoquinone; TQNLC, thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers.

HPLC and PK studies

As shown in Figure 7, under the experimental conditions used in this study, the observed retention times of TQ and the IS were 4.4 and 7.8 minutes, respectively, indicating good separation between the compounds. As also shown in Figure 7, the elution time of TQ is close to that of zerumbone; thus, zerumbone was used as the IS in this study. For rabbit plasma, the method was found to be linear across six concentration points in the range of 10–60 ng/mL, with the coefficient of determination (r2) = 0.9981. The recovery of TQ and the IS was found to be 92.0% and 90.11%, respectively, when mixed at a ratio of 1:8 (matrix: solvent ratio). The intraday and interday precision (RSD%) and the RE% of the three quality control concentration points at 12, 35, and 50 ng/mL were found to be in the range of 0.79% to 1.81%, 1.52% to 2.67%, and −3.20% to 0.26%, respectively. TQ was found to be stable in rabbit plasma, with an RSD% of 0.51% to 1.54% and an RE% of −1.71% to −6.4%, when stored in the autosampler (19°C–22°C); with an RSD% of 0.75% to 2.1% and an RE% of −2.95% to −0.7%, following three cycles of freeze-thaw; and with an RSD% of 0.52% to 2.7% and an RE% of −3.9% to −1.69%, following storage for 2 weeks. Figure 7 shows the mean (±SD) plasma concentration–time profiles of TQ in rabbits following administration of a single extravascular dose of 10 mg/kg (n = 3). Based on these results, the method is suitable to determine TQ concentrations in rabbit plasma. The results of the PK study should be reconfirmed in future investigations using a larger number of animals.

Figure 7.

HPLC chromatogram of a rabbit plasma sample collected 4 hours following extravascular administration of TQ prepared in a nanoparticle solution, namely, TQNLC(20), at a dose of 10 mg/kg.

Abbreviations: AU, Area under the curve; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; TQ, thymoquinone; TQNLC, thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers.

After validation, the PK studies were conducted in rabbits. The mean plasma concentration-time profiles of TQ following the administration of the TQ formulated in the nanoparticles and the estimated mean PK parameters are listed in Table 2. From Table 2, it is clear that extravascular administration of TQ improved its PK properties in this animal model; the AUC0-∞, Vd (volume of distribution), and CL (clearance) were found to be 26821.61 ± 9.40 ng · h/mL, 4.32 ± 0.34 L/kg, and 0.71 ± 0.031 L/h/kg, respectively, indicating that the drug had a linear PK profile. However, this assumption needs further investigation, with the study of the PK properties of TQ in vivo, using multiple doses of TQ. The time needed to reach maximum concentration (Tmax), maximum concentration achieved in the blood (Cmax), and elimination half-life (T1/2) of TQ were found to be 3.96 ± 0.19 hours, 4811.33 ± 55.52 ng/mL, and 4.4933 ± 0.015 hours, respectively, indicating that TQ is suitable for extravascular administration using the aforementioned nanoparticle formulation. Previous in vivo studies has also revealed an increase in the bioavailability of nanoformulated TQ.44,45

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of TQ in rabbits following a single extravascular dose of TQNLCs (n = 3)

| Parametersa | TQNLC (extravascular) 10 mg/kgb |

|---|---|

| Tmax (hours) | 3.96 ± 0.19 |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 4811.33 ± 55.52 |

| AUC0-∞ (ng·h/mL) | 26821.61 ± 9.40 |

| Vd (L/kg) | 4.32 ± 0.34 |

| CL (L/h/kg) | 0.71 ± 0.031 |

| t1/2 (hours) | 4.4933 ± 0.015 |

| λz (h−1) | 0.1547 ± 0.003 |

Notes:

Pharmacokinetic parameters are represented by the mean ± SD (n = 3);

ρ < 0.05.

Abbreviations: AUC0-∞, area under the concentration-time curve from zero to infinity; CL, clearance; Cmax, maximum concentration achieved in the blood; SD, standard deviation; t1/2 elimination half-life; Tmax, time needed to reach maximum concentration; TQ, thymoquinone; TQNLC, thymoquinone-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers; Vd, volume of distribution; λz, terminal elimination rate constant.

Conclusion

In conclusion, NLCs composed of solid and liquid lipids and surfactants are potentially good colloidal drug carriers for TQ. The average diameter of TQNLC(20) loaded with TQ was less than 100 nm, with a perfect negative zeta potential value and melting peak. The loading of TQ into NLCs significantly improved the gastroprotective properties of this natural compound against the formation of ethanol-induced ulcers, by modulating Hsp70. Acute hepatotoxic effects of TQNLC(20) in rats and normal human liver cells (WRL-68) were not observed. Validated PK studies showed that the drug behaved linearly, following extravascular administration. In conclusion, NLCs could be a promising vehicle for the oral delivery of TQ.

Acknowledgments

This research was graciously supported by the Scientific Chair for Prophetic Medicine and Scientific Miracle (Grant No: SMPM1434/A0103).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Burits M, Bucar F. Antioxidant activity of Nigella sativa essential oil. Phytother Res. 2000;14(5):323–328. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200008)14:5<323::aid-ptr621>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali BH, Blunden G. Pharmacological and toxicological properties of Nigella sativa. Phytother Res. 2003;17(4):299–305. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo CC, Kumar AP, Sethi G, Tan KH. Thymoquinone: potential cure for inflammatory disorders and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83(4):443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ammar el-SM, Gameil NM, Shawky NM, Nader MA. Comparative evaluation of anti-inflammatory properties of thymoquinone and curcumin using an asthmatic murine model. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11(12):2232–2236. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mariod AA, Ibrahim RM, Ismail M, Ismail N. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of phenolic rich fractions obtained from black cumin (Nigella sativa) seedcake. Food Chem. 2009;116(1):306–312. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourgou S, Pichette A, Marzouk B, Legault J. Bioactivities of black cumin essential oil and its main terpenes from Tunisia. S Afr J Bot. 2010;76(2):210–216. [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Abhar HS, Abdallah DM, Saleh S. Gastroprotective activity of Nigella sativa oil and its constituent, thymoquinone, against gastric mucosal injury induced by ischaemia/reperfusion in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84(2–3):251–258. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravindran J, Nair HB, Sung B, Prasad S, Tekmal RR, Aggarwal BB. Thymoquinone poly (lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles exhibit enhanced anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and chemosensitization potential. Biocheml Pharmacol. 2010;79(11):1640–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Zaoui A, Cherrah Y, Lacaille-Dubois MA, Settaf A, Amarouch H, Hassar M. [Diuretic and hypotensive effects of Nigella sativa in the spontaneously hypertensive rat] Therapie. 2000;55(3:):379–382. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salem ML. Immunomodulatory and therapeutic properties of the Nigella sativa L seed. Int Immunopharmacol. 2005;5(13–14):1749–1770. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanter M, Demir H, Karakaya C, Ozbek H. Gastroprotective activity of Nigella sativa L oil and its constituent, thymoquinone against acute alcohol-induced gastric mucosal injury in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(42):6662–6666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i42.6662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyder MAH. [Nanotechnology and Environment: Potential Applications and Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology] [master’s thesis] Hamburg: Hamburg University of Technology; 2003. German. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller RH, Radtke M, Wissing SA. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) in cosmetic and dermatological preparations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(Suppl 1):S131–S155. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcato PD, Durain N. New aspects of nanopharmaceutical delivery systems. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2008;8(5):2216–2229. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2008.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shidhaye SS, Vaidya R, Sutar S, Patwardhan A, Kadam VJ. Solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers – innovative generations of solid lipid carriers. Curr Drug Deliv. 2008;5(4):324–331. doi: 10.2174/156720108785915087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patidar A, Thakur DS, Kumar P, Verma J. A review on novel lipid based nanocarriers. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2010;2(4):30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raffin RP, Colomé LM, Pohlmann AR, Guterres SS. Preparation, characterization, and in vivo anti-ulcer evaluation of pantoprazole-loaded microparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2006;63(2):198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arias J, Clares B, Morales M, Gallardo V, Ruiz MA. Lipid-based drug delivery systems for cancer treatment. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12(8):1151–1165. doi: 10.2174/138945011795906570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller RH, Mäder K, Gohla S. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery – a review of the state of the art. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50(1):161–177. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiruganesh R, Uma Devi SK. Solid lipid nanoparticle and nanoparticle lipid carrier for controlled drug delivery – a review of state of art and recent advances. Intl J of Nanoparticles. 2010;3(1):32–52. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauss DJ. Oral lipid-based formulations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59(7):667–676. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar H, Dharamveer KMK, Saraf AS. Preparation, characterization and in vivo anti-ulcer evaluation of ranitidine-loaded floating microparticles; Proceedings of the National Conference on Innovations in Drug Delivery and Research; March 3–5, 2009; Patiala, India. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardoso T, Galhano CIC, Ferreira Marques MF, Moreira da Silva A. Thymoquinone beta-Ccyclodextrin nanoparticles system: a preliminary study. Journal of Spectroscopy. 2012;27(5–6):329–336. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam S, Khan ZI, Mustafa G, et al. Development and evaluation of thymoquinone-encapsulated chitosan nanoparticles for nose-to-brain targeting: a pharmacoscintigraphic study. Int J Nanomedicine. 20112;7:5705–5718. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S35329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.How CW, Abdullah R, Abbasalipourkabir R. Physicochemical properties of nanostructured lipid carriers as colloidal carrier system stabilized with polysorbate 20 and polysorbate 80. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10(9):1684–1689. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potrich FB, Allemand A, da Silva LM, et al. Antiulcerogenic activity of hydroalcoholic extract of Achillea millefolium L: involvement of the antioxidant system. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130(1):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan PV, Nyasse B, Dimo T, Mezui C. Gastric cytoprotective anti-ulcer effects of the leaf methanol extract of Ocimum suave (Lamiaceae) in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;82(2):69–74. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Njar VCO, Adesanwo JK, Raji Y. Methyl angolensate: The antiulcer agent from the stem bark of Entandrophragma angolense. Planta Med. 1995;61(1):91–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behmer OA. Manual de Técnicas para Histologia Normal e Patológica [Technical Manual for Normal and Pathological Histology] São Paulo: Edart; 1976. Portuguese. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vacca LL. Laboratory Manual of Histochemistry. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eid EEM, Abdul AB, Al-Zubairi AS, Sukari MA, Abdullah R. Validated high performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) method for analysis of zerumbone in plasma. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9(8):1260–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seetapan N, Bejrapha P, Srinuanchai W, Ruktanonchai UR. Rheological and morphological characterizations on physical stability of gamma-oryzanol-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) Micron. 2010;41(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Z, Hua SC, Yang YL, Fang JY. Development and evaluation of lipid nanoparticles for camptothecin delivery: a comparison of solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, and lipid emulsion. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29(9):1094–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.How CW, Abdullah R, Abbasalipourkabir R. Characterization and cytotoxicity of nanostructured lipid carriers formulated with olive oil, hydrogenated palm oil and polysorbate 80. IEEE Trans Nanobioscience. 2012 Dec 20; doi: 10.1109/TNB.2012.2232937. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong HL, Bendayan R, Rauth AM, Li Y, Wu XY. Chemotherapy with anticancer drugs encapsulated in solid lipid nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59(6):491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puri A, Loomis K, Smith B, et al. Lipid-based nanoparticles as pharmaceutical drug carriers: from concepts to clinic. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2009;26(6):523–580. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v26.i6.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly S, Hunter JO. Epidermal growth factor stimulates synthesis and secretion of mucus glycoproteins in human gastric mucosa. Clin Sci (Lond) 1990;79(5):425–427. doi: 10.1042/cs0790425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris GP, Wallace JL. The roles of ethanol and of acid in the production of gastric mucosal erosions in rats. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1981;38(1):23–38. doi: 10.1007/BF02892800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andreo MA, Ballesteros KVR, Hiruma-Lima CA, Machado da Rocha LR, Souza Brito AR, Vilegas W. Effect of Mouriri pusa extracts on experimentally induced gastric lesions in rodents: role of endogenous sulfhydryls compounds and nitric oxide in gastroprotection. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107(3):431–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramteke S, Jain NK. Clarithromycin-and omeprazole-containing gliadin nanoparticles for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori. J Drug Target. 2008;16(1):65–72. doi: 10.1080/10611860701733278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lupidi G, Camaioni E, Khalifé H, Avenali L, Damiani E, Tanfani F. Characterization of thymoquinone binding to human α1-acid glycoprotein. J Pharmaceut Sci. 2012;101:2564–2573. doi: 10.1002/jps.23138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tajau R, Dahlan KZM, Mahmood MH, et al. Acrylated vegetable oil nanoparticle as a carrier and controlled release of the anticancer drug-thymoquinone Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Enabling Science and NanotechnologyJanuary 5–7, 2012IEEE Conference Publications; 2012Available from: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/loginjsp?tp=&arnumber=6149656&url=http%3A%2F%2Fieeexplore.ieee.org%2Fstamp%2Fstamp.jsp%3Ftp%3D%26arnumber%3D6149656Accessed April 14, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collnot EM, Ali H, Lehr CM. Nano-and microparticulate drug carriers for targeting of the inflamed intestinal mucosa. J Control Release. 2012;161(2):235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh A, Ahmad I, Akhter S, et al. Nanocarrier based formulation of thymoquinone improves oral delivery: stability assessment, in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2013;102:822–832. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pathan SA, Jain GK, Zaidi S, et al. Stability-indicating ultra-performance liquid chromatography method for the estimation of thymoquinone and its application in biopharmaceutical studies. Biomed Chromatogr. 2011;25(5):613–620. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]