Abstract

Statins are an extensively used class of drugs, and myopathy is an uncommon, but well-described side effect of statin therapy. Inflammatory myopathies, including polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and necrotizing autoimmune myopathy, are even more rare, but debilitating, side effects of statin therapy that are characterized by the persistence of symptoms even after discontinuation of the drug. It is important to differentiate statin-associated inflammatory myopathies from other self-limited myopathies, as the disease often requires multiple immunosuppressive therapies. Drug interactions increase the risk of statin-associated toxic myopathy, but no risk factors for statin-associated inflammatory myopathies have been established. Here we describe the case of a man, age 59 years, who had been treated with a combination of atorvastatin and gemfibrozil for approximately 5 years and developed polymyositis after treatment with omeprazole for 7 months. Symptoms did not resolve after discontinuation of the atorvastatin, gemfibrozil, and omeprazole. The patient was treated with prednisone and methotrexate followed by intravenous immunoglobulin, which resulted in normalization of creatinine kinase levels and resolution of symptoms after 14 weeks. It is unclear if polymyositis was triggered by interaction of the statin with omeprazole and/or gemfibrozil, or if it developed secondary to long-term use of atorvastatin only.

Keywords: Autoimmune, Myopathy, Statins

Statins are an extensively used class of drugs. According to a report from the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics,1 close to 94 million individual prescriptions for generic simvastatin were issued in 2010. Myopathy is an uncommon, but well-described side effect of statin therapy. Drug interactions increase the risk of statin-associated myopathy by as much as ten-fold.2 Statin-associated myopathies generally resolve after discontinuation of the drug; however, in rare cases of statin-associated autoimmune myopathy, symptoms may persist or worsen after the drug is discontinued, requiring immunosuppressive therapy.3 Polymyositis is a rare side effect of statin therapy that is characterized by symmetric proximal muscle weakness and the persistence of symptoms even after discontinuation of the drug. Here we describe a patient with probable polymyositis in whom drug interactions may have played a role.

Case Presentation

A man, age 59 years, presented in September 2011 with complaints of insidious onset of weakness, muscle soreness, and trouble climbing stairs for 5 months. The patient had symptoms in both upper and lower extremities, but his symptoms were more pronounced in the hip flexors. He described his symptoms as gradually worsening and denied any history of viral illness or fever.

The patient’s medical history was significant for ST-elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) in April 2006, for which he had been treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stent placement and had been started on atorvastatin 20 mg daily; 3 months later gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily was added. In September 2010, the patient had symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and dysphagia, for which he underwent esophago-gastroduodenoscopy with findings of mild distal peptic esophagitis and relatively patent Schatzki’s ring. Balloon dilation of the esophagus was performed, and he was started on omeprazole 20 mg daily. He denied use of tobacco or alcohol. Other home medications included amlodipine, aspirin, nitrate, and metoprolol. Atorvastatin, gemfibrozil, and omeprazole were stopped in August 2011 secondary to muscle soreness. The patient had no known history of endocrinopathy, neurogenic disease, exposure to other myotoxic drugs, any symptoms suggestive of underlying malignancy, or family history of neuromuscular disease.

Upon physical examination, the patient scored 5/5 on strength of the upper extremities and 4/5 on strength of lower extremities (hip flexors, ileopsoas), indicating he was able to raise the leg only against slight resistance, but not against full resistance. The issue appeared to be localized to the ileopsoas, as strength in the quadriceps was 5/5. Sensation was intact for pin and vibration, and reflexes were intact. Physical exam was otherwise normal, including extraocular and facial muscles, and there was no evidence of rash.

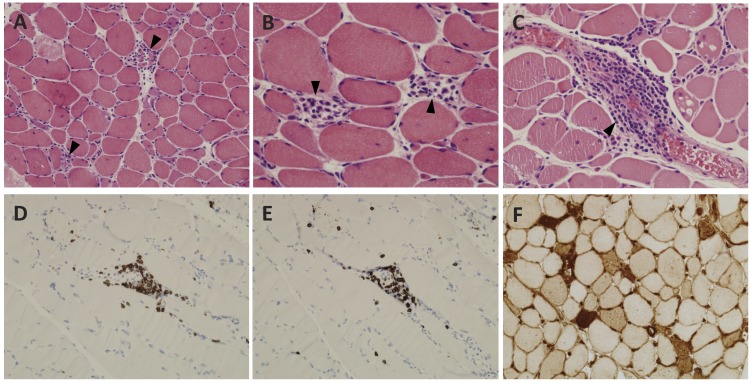

The patient had been on atorvastatin and gemfibrozil for approximately 5 years without any muscle symptoms. Seven months after starting omeprazole, he began experiencing muscle soreness and weakness. The patient’s serum creatinine kinase (CK) level at the time of presentation was highly elevated at 10,554 U/L (normal 50–235 U/L) compared to a level of 700 U/L in April of 2006. Table 1 details CK levels over time. Atorvastatin, gemfibrozil, and omeprazole were stopped, but the patient remained symptomatic with persistent CK levels >10,000 U/L that reached as high as 11,831 U/L in September, one month after presentation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the bilateral thighs was performed with intravenous administration of 20 mL gadolinium contrast agent. MRI with axial and coronal T1-weighted and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences showed an abnormal mild increase in STIR signal and enhancement of the bilateral posterior thigh musculature, especially involving the bilateral hamstring and adductor muscles (figure 1), compatible with polymyositis, rhabdomyolysis, or an inflammatory neuropathy. A biopsy was obtained from the left posterior thigh muscle and revealed findings consistent with acute necrotizing myopathy, including countless necrotic and regenerating fibers (figures 2A and 2B) with focally prominent perivascular perimysial and endomysial inflammation composed of mature lymphocytes and macrophages (figure 2C). Immunohistochemical studies revealed that the lymphocytic infiltrates were composed of CD3- and CD8-positive cytotoxic T-cells (figure 2D and 2E). A major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-1 immunostain showed patchy membranous reactivity with accentuation around necrotic fibers and foci of perivascular inflammation (figure 2F). Laboratory results were negative for all autoantibodies tested including antinuclear antibody (ANA), ds-DNA, chromatin, ribonucleoprotein P, Sjogrens antibodies SSA and SSAB, centromere B, SM, SnRNP, SCL-70, and Jo1. Antibodies to hepatitis A, B, and C were also negative. Testing for anti-SRP and other non-Jo1 anti-synthetase autoantibodies was not performed.

Table 1.

Creatinine kinase (CK) levels over time.

| Date | CK (U/L) |

|---|---|

| April 2006 | 700 |

| August 2011 | 10,554 |

| September 2011 | 11,831 |

| October 2011 | 4,771 |

| November 2011 | 3,137 |

| December 2011 | 1,414 |

| January 2012 | 118 |

| March 2012 | 65 |

Figure 1.

MRI of lower extremities showing T1 flat saturation sequences. (A) Coronal section and (B) axial section showing inflammation in the posterior (bottom of image) thigh muscles with relative sparing of the anterior and medial compartments. Arrows indicate areas of inflammation.

Figure 2.

Histopathological analysis of left posterior thigh biopsy with evidence of acute necrotizing myopathy. (A) Active necrotizing myopathy with concurrent areas of regeneration, H&E, ×100. (B) Higher power detail of areas of myofiber regeneration, H&E, ×400. (C) Perimysial vascular lymphocytic infiltrates, H&E, ×400. (D) CD3 immunohistochemical stain highlights T-cells in perivascular infiltrates, DAB chromogen with hematoxylin counterstain, ×100. (E) CD8 immunohistochemical stain highlights cytotoxic T-cells, DAB chromogen with hematoxylin counterstain, ×100. (F) MHC-1 immunohistochemical stain highlighting diffuse positive membranous reactivity, with accentuation in necrotic and regenerating fibers, DAB chromogen, ×200.

Based on the muscle biopsy report and clinical presentation, the patient was suspected of having polymyositis and was started on prednisone and methotrexate. Oral prednisone was started at 80 mg/day for 7 weeks, then gradually tapered by 10 mg/month for 2 months followed by 5 mg/month for 3 months, which still continues. Oral methotrexate was started at 15–20 mg/week for 12 weeks, and the patient continues to receive 20 mg/week, subcutaneously. Prednisone and methotrexate administration resulted in a decrease in serum CK levels from 11,831 U/L in September 2011 to 4772 U/L in October 2011, but muscle weakness did not subside. Three doses of intravenous immunoglobulin of 40 g, 60 g, and 60 g were administered over a one-month period in November and December 2011, resulting in a further decrease in serum CK levels to 778 U/L. The patient tolerated the medications well without side effects. By 14 weeks of treatment, CK levels had fallen to within the normal range (180 U/L), and the patient’s muscle weakness had disappeared such that strength in the hip flexors (ileopsoas) had returned to 5/5. At last follow-up after 24 weeks of treatment, his serum CK levels were within normal range at 65 U/L, and he was continuing on prednisone 20 mg/day orally and methotrexate 20 mg/week subcutaneously.

Discussion

Statins are used extensively to lower serum cholesterol as well as for primary and secondary prevention of coronary events and stroke.4 Myopathy is a rare but well-documented side effect associated with statin use and ranges from myalgia to myositis to overt rhabdomyolysis.5,6 Onset of muscle symptoms usually occurs within weeks to months of statin therapy initiation, and symptoms resolve within months of drug discontinuation.7 Several possible mechanisms of statin-associated muscle toxicity have been proposed, but the answer remains unclear. Theories suggested are primarily downstream of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition and include instability of skeletal muscle cell membranes by blocking of cholesterol synthesis,8 decreased synthesis of coenzyme Q10 and mitochondrial dysfunction,9,10 inhibition of GTP-binding regulatory proteins, and impairment of muscle’s ability to appropriately recover from physical exertion.11,12 While statins can cause myopathy during monotherapy, many cases are associated with drug interactions. Drugs of particular concern include CYP3A4 isoenzyme-dependent drugs such as macrolide antibiotics, azole antifungals, and cyclosporine,12–14 drugs that interact with the glucuronidation pathway such as gemfibrozil,12 and drugs that interact with the p-glycoprotein efflux system such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).2,15–17 There are many reports in the literature of an increased incidence of myopathy with use of statins combined with gemfibrozil,18 as well as case reports of rhabdomyolysis and polymyositis associated with the use of omeprazole and other PPIs in combination with statin therapy.2,19,20

In addition to the self-limited, toxic myopathy associated with statins, there are reports of statin-associated inflammatory myopathies including polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and necrotizing autoimmune myopathy that are characterized by elevated CK levels and proximal muscle weakness during or after statin use that persists even after discontinuation of the drug. Symptoms improve with immunosuppressive therapy, but many patients require treatment with multiple agents including steroids, steroid-sparing agents, and intravenous immunoglobulin,21 as in the case reported here. Diagnostic criteria for polymyositis include: symmetric proximal muscle weakness progressing over weeks to months; muscle biopsy demonstrating myofiber necrosis, phagocytosis, regeneration, variation in fiber diameter, and an inflammatory exudate; elevation of serum skeletal muscle enzymes; and electromyography showing low-amplitude, small, polyphasic motor units.22 The patient presented here meets three of the four diagnostic criteria, making this a probable case of polymyositis.

The histopathological findings described in the muscle biopsies of patients with polymyositis show necrotic and regenerating muscle fibers with a characteristic endomysial inflammatory infiltrate rich in CD8 T cells and increased MHC-1 expression on non-necrotic muscle fibers.3 Although the clinical presentation of several inflammatory myopathies is similar, histology allows for differentiation of the diagnoses. Histologically, dermatomyositis is similar to polymyositis, except that the infiltrate is composed primarily of CD4 T cells.3 The characteristic rash is a further distinguishing characteristic. In contrast, necrotizing autoimmune myopathy is notable for the relative absence of inflammatory cells on histology.3

Autoantibodies are frequently detected in patients with autoimmune myopathies. The patient presented here was negative for autoantibodies against ANA and Jo1, but he was not tested for antibodies against HMG-CoA, anti-SRP, and non-Jo1 anti-synthetase antibodies. Antibodies against HMG-CoA are more typical of necrotizing autoimmune myositis than polymyositis.22 Patients with anti-SRP antibodies are very rarely found to have collections of inflammatory cells on biopsy, and those with anti-synthetase antibodies tend to present with additional anti-synthetase syndrome-specific clinical features in addition to myopathy;22 however, due to lack of testing, these autoantibodies cannot be ruled out.

The presence of inflammatory CD8 T cells upon biopsy and the overall clinical picture of widespread necrosis and regeneration is most consistent with polymyositis. In the case of statin-associated inflammatory myopathies, symptoms may occur years after the start of statin treatment or even after discontinuation of statin use.24 In the case presented here, we are not sure if polymyositis was triggered by interaction with omeprazole and/or gemfibrozil, or if it developed secondary to long-term use of atorvastatin only. Of note, the patient’s CK levels were relatively high (700 U/L) 5 years before presentation, which may have indicated an underlying polymyositis that was later exacerbated or unmasked by use of a statin, gemfibrozil, and omeprazole. As previously mentioned, omeprazole and gemfibrozil have been reported to cause toxic myopathy with statins, but the incidence of polymyositis is rare.

Conclusion

Polymyositis is a rare but serious statin side effect that can occur years after initiation of therapy and persists after discontinuation of the drug, in contrast to the self-limiting toxic myopathy more frequently associated with short-term statin use. It is important to differentiate statin-associated inflammatory myopathies from other self-limited myopathies, because the disease will not subside following discontinuation of the drug, and treatment often requires multiple immunosuppressive agents. Drug interactions increase the risk of statin-associated toxic myopathy, and while no risk factors for statin-associated polymyositis have been established, drug interactions may play a role and deserve further investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication for assistance in preparing this manuscript.

References

- 1.The Use of Medicines in the United States: Review of 2010, April 2011. IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics website. Available at: www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Conent/IMS%20Institute/State%20File/IHII_UseOfMed_report.pdf Accessed April 3, 2012

- 2.Sipe BE, Jones RJ, Bokhart GH. Rhabdomyolysis causing AV blockade due to possible atorvastatin, esomeprazole, and clarithromycin interaction. Ann Pharmacother 2003; 37:808–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padala S, Thompson PD. Statins as a possible cause of inflammatory and necrotizing myopathies. Atherosclerosis 2012;222:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LIPID Study Group Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patient with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundy SM. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors for treatment of hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 1988;319:24–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson PD, Clarkson PM, Rosenson RSNational Lipid Association Statin Safety Task Force Muscles Safety Expert Panel An assessment of statin safety by muscle experts. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:69C–76C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen KE, Hildebrand JP, Ferguson EE, Stein JH. Outcomes in 45 patients with statin-associated myopathy. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:2671–2676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Päivä H, Thelen KM, Van Coster R, Smet J, De Paepe B, Mattila KM, Laakso J, Lehtimäki T, von Bergmann K, Lütjohann D, Laaksonen R. High-dose statins and skeletal muscle metabolism in humans: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005;78:60–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghirlanda G, Oradei A, Manto A, Lippa S, Uccioli L, Caputo S, Greco AV, Littarru GP. Evidence of plasma CoQ10-lowering effect by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Clin Pharmacol 1993;33:226–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rundek T, Naini A, Sacco R, Coates K, DiMauro S. Atorvastatin decreases the coenzyme Q10 level in the blood of patients at risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke. Arch Neurol 2004;61:889–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren JD, Blumbergs PC, Thompson PD. Rhabdomyolosis: a review. Muscle Nerve 2002;25:332–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA 2003;289:1681–1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ucar M, Mjörndal T, Dahlgvist R. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and myotoxicity. Drug Saf 2000;22:441–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omar MA, Wilson JP, Cox TS. Rhabdomyolysis and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother 2001; 35:1096–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd RA, Stern RH, Stewart BH, Wu X, Reyner EL, Zegarac EA, Randinitis EJ, Whitfield L. Atorvastatin coadministration may increase digoxin concentrations by inhibition of intestinal P-glycoprotein-mediated secretion. J Clin Pharmacol 2000;40:91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogman K, Peyer AK, Török M, Küsters E, Drewe J. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and P-glycoprotein modulation. Br J Pharmacol 2001;132:1183–1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pauli-Magnus C, Rekersbrink S, Klotz U, Fromm MF. Interaction of omeprazole, lansoprazole and pantoprazole with P-glycoprotein. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2001;364:551–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson TA. Myopathy with statin-fibrate combination therapy: clinical considerations. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2009;5:507–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nozaki M, Suzuki T, Hirano M. Rhabdomyolysis associated with omeprazole. J Gastroenterol 2004;39:86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark DW, Strandell J. Myopathy including polymyositis: a likely class adverse effect of proton pump inhibitors? Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:473–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalakas MC. Inflammatory myopathies: management of steroid resistance. Curr Opin Neurol 2011;24:457–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mammen AL. Autoimmune myopathies: autoantibodies, phenotypes and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7:343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grable-Esposito P, Katzberg HD, Greenberg SA, Srinivasan J, Katz J, Amato AA. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins. Muscle Nerve 2010;41:185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sailler L, Pereira C, Bagheri A, Uro-Coste E, Roussel B, Adoue D, Fournie B, Laroche M, Zabraniecki L, Cintas P, Arlet P, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL. Increased exposure to statins in patients developing chronic muscle diseases: a 2-year retrospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]