Abstract

The A28L gene of vaccinia virus is conserved in all poxviruses and encodes a protein that is anchored to the surface of infectious intracellular mature virions (IMV) and consequently lies beneath the additional envelope of extracellular virions. A conditional lethal recombinant vaccinia virus, vA28-HAi, with an inducible A28L gene, undergoes a single round of replication in the absence of inducer, producing IMV, as well as extracellular virions with actin tails, but fails to infect neighboring cells. We show here that purified A28-deficient IMV appeared to be indistinguishable from wild-type IMV and were competent to synthesize RNA in vitro. Nevertheless, A28-deficient virions did not induce cytopathic effects, express early genes, or initiate a productive infection. Although A28-deficient IMV bound to the surface of cells, their cores did not penetrate into the cytoplasm. An associated defect in membrane fusion was demonstrated by the failure of low pH to trigger syncytium formation when cells were infected with vA28-HAi in the absence of inducer (fusion from within) or when cells were incubated with a high multiplicity of A28-deficient virions (fusion from without). The correlation between the entry block and the inability of A28-deficient virions to mediate fusion provided compelling evidence for a relationship between these events. Because repression of A28 inhibited cell-to-cell spread, which is mediated by extracellular virions, all forms of vaccinia virus regardless of their outer coat must use a common A28-dependent mechanism of cell penetration. Furthermore, since A28 is conserved, all poxviruses are likely to penetrate cells in a similar way.

Poxviruses are among the largest and most complex of animal viruses (30). Vaccinia virus, the best-characterized member of the family, has a double-stranded DNA genome of ca. 195 kbp, which encodes nearly 200 proteins. Although vaccinia virus has been studied extensively, several fundamental aspects of its biology, such as the mode of entry into host cells, remain poorly understood. The investigation of viral entry is complicated by the existence of infectious viral forms with different outer membranes that can promiscuously infect virtually all cultured animal cells. The initial viral membrane, which consists of one or two closely apposed lipoprotein bilayers (15, 35, 48), is formed by an undetermined mechanism during an early step in virus assembly and becomes the coat of infectious intracellular mature virions (IMV). Most IMV remain within the cytoplasm of the intact cell and are only released upon cell lysis. Electron micrographs suggest that some IMV bud through the plasma membrane (29, 52), whereas a double membrane derived from trans-Golgi or endosomal cisternae wrap other IMV (13, 43, 50). These wrapped IMV, known as intracellular enveloped virions (IEV), are transported on microtubules to the periphery of the cell (11, 14, 34, 59, 60), where the outer IEV and plasma membranes fuse. The externalized virions contain one additional membrane relative to IMV and some, called cell-associated enveloped virions, adhere to the cell surface at the tips of actin-containing microvilli (4, 49) and some dissociate from the cell-forming extracellular enveloped virions (EEV) (5, 31). Cell-associated enveloped virions and EEV can mediate cell-to-cell and longer-range spread, respectively.

Although IMV and EEV are both infectious, their outer membranes have different origins and viral protein components and consequently bind different, although unidentified, cell surface receptors (55). Some experiments suggest that IMV enter cells by fusion with the plasma membrane or vesicles formed by surface invaginations in a pH-independent manner (6, 9, 22), although nonfusion mechanisms have also been considered (28). Treating virions with proteinases (21) or phosphatidylserine enhances cell penetration (19). EEV infection can be partially inhibited by lysosomotropic agents, suggesting that endocytosis, followed by acid disruption of the EEV outer membrane occurs, perhaps followed by fusion of the released IMV with the vesicle membrane (18, 56). The fusion of infected cells, triggered by short exposure to a low pH (fusion from within), may mimic the latter process by disrupting the outer membrane of enveloped particles on the cell surface (9, 12). However, the low-pH treatment also triggers cell fusion induced by the addition of large quantities of purified IMV to cells (fusion from without) (12). In addition, mutations of the orthopoxvirus hemagglutinin (44) or SPI-3 (25, 53, 68) gene result in a pH-independent cell fusion phenotype.

About a dozen viral proteins have been localized to the IMV membrane. Some of them, namely, L1 (33), A17 (36, 63), A14 (40, 51), A9 (65), E10 (46), and A2.5 (45), are essential for virus replication in cell culture. Repression of the synthesis of any of the above proteins prevents or interrupts virion morphogenesis, largely precluding investigations into possible additional roles of these proteins in entry. A role of the L1 membrane protein in cell penetration, however, was suggested by the ability of anti-L1 antibody to neutralize virions already attached to cells (20, 64). Three IMV membrane proteins, encoded by the A27L, D8L, and H3L open reading frames are targets of neutralizing antibodies and contribute to cell attachment by binding to glycosaminoglycans in the plasma membrane (7, 17, 26, 37, 57). The A27 protein also has roles in fusion (9, 12), microtubule-dependent movement of IMV (42), and formation of IEV (39).

The gene encoding A28, a recently identified IMV membrane protein, is highly conserved in all sequenced vertebrate and invertebrate poxviruses (44a). The conserved features of A28 include an N-terminal hydrophobic domain that anchors the protein in the IMV membrane and four cysteines that form two intramolecular disulfide bonds (44a) via a recently discovered virus-encoded redox pathway (47). Studies with the inducible vaccinia virus mutant vA28-HAi revealed that A28 is required for virus propagation (44a). We had expected that the inducer-dependent A28R mutant would have a defective morphogenesis phenotype, similar to that of a mutant with an inducible L1R gene (33). Unexpectedly, the conditional A28R null mutant exhibited no apparent assembly defect, and intracellular and extracellular virions were formed (44a). Here, we demonstrate that purified A28-deficient IMV bind to cells, but the cores are unable to penetrate into the cytoplasm. Furthermore, in the absence of A28, the recombinant virus did not induce cell fusion from within or without. The present study demonstrated important links between a viral membrane protein, virus entry, and low pH-mediated fusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Standard procedures were used for the preparation and maintenance of BS-C-1 cells (ATCC CCL-26) and HeLa S3 cells (ATCC CCL-2.2) and for the propagation and titration of vaccinia virus (10). IMV was purified essentially as described previously (10) with special care to remove the inoculum virus. Cells infected with wild-type vaccinia virus WR or with vA28-HAi in the presence or absence of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) were washed three times after a 1-h adsorption period. After a further 24 h, the cells were harvested and collected by centrifugation. The cells were Dounce homogenized, and virus in the postnuclear supernatant was purified twice through a 36% sucrose cushion to remove membranes and then banded on a 25 to 40% sucrose gradient.

Sources of antibodies.

Mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) C3 to the vaccinia virus protein A27 (38), MAb 7D11 to L1 (64), and peroxidase-conjugated rat high-affinity anti-hemagglutinin (HA) MAb (3F10; Roche Molecular Biochemicals) were used. The following rabbit polyclonal antibodies against vaccinia virus proteins were used: anti-L1 (32), anti-A17 (2), anti-A4 (8), and anti-p4b/4b (R. Doms and B. Moss, unpublished data).

Western blot analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting were carried out with appropriate antibodies essentially as described in the accompanying report (44a).

RNA synthesis by detergent-permeabilized virions.

Indicated amounts of purified virions were incubated in 20 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40, 5 mM ATP, 1 mM GTP, 1 mM CTP, 0.02 mM UTP, and 1 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (3,000 Ci/mmol). Incorporation of [α-32P]UMP into trichloroacetic acid-insoluble material was determined by scintillation counting.

Fluorescence microscopy.

HeLa cells were grown on coverslips and infected with 10 PFU of vaccinia virus per cell. Virus was adsorbed to the cells at room temperature or 4°C, and the cells were washed three times before they were moved to a 37°C incubator. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 4°C, followed by 40 min at room temperature. In some experiments, the cells were permeabilized in 0.05% saponin-phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with antibodies in 0.05% saponin-phosphate-buffered saline-10% fetal calf serum, followed by an appropriate secondary fluorescent antibody. DNA was visualized by staining with 5 μg of diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Molecular Probes) per ml for 5 min. Filamentous actin was visualized by staining with Alexa Fluor 568 phalloidin (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer's directions. Images were collected on a Leica TCS-NT/SP2 inverted confocal microscope system with an attached argon ion laser (Coherent, Inc.).

Northern blotting.

BS-C-1 cells in a standard 12-well plate were pretreated for 1.5 h with 40 μg of cytosine arabinoside (AraC) per ml and infected with 10 PFU of vA28-HAi per cell in the presence or absence of 100 μM IPTG. AraC was present continuously throughout infection. At 4 h after infection, cells were collected and total RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA species were resolved by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon filter, and hybridized to DNA probe by using NorthernMax-Plus kit (Ambion). The 32P-labeled DNA probes were prepared by using Random Primers DNA Labeling System (Invitrogen). Radioactive bands were detected with the Typhoon 8600 (Molecular Dynamics) PhosphorImager.

Immunoprecipitation.

BS-C-1 cells in a standard 12-well plate were infected with 10 PFU of vA28-HAi per cell in the presence or absence of 100 μM IPTG and labeled with [35S]methionine for 5 h. Cells were collected, extracted with 1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline, and incubated with protein A-agarose beads that were preloaded with an antibody. The antigen-antibody complexes on protein A-beads were washed and then disrupted in SDS-polyacrylamide gel loading buffer. Proteins were resolved by PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and visualized by autoradiography.

Abbreviations.

Vaccinia virus open reading frames are designated by a capital letter indicating a HindIII restriction endonuclease fragment, a number indicating the position in the HindIII fragment, and a letter (L or R) indicating the direction of transcription, e.g., A28L. The corresponding protein is designated by a capital letter and number, e.g., A28.

RESULTS

A28 is required for virion infectivity.

In a related study (44a), we described the construction of two recombinant vaccinia viruses: vA28-HA and vA28-HAi. The first recombinant virus, vA28-HA, replicates normally, although it has an influenza virus HA epitope tag coding sequence at the 3′ terminus of the otherwise unmodified A28L gene. In the second recombinant vaccinia virus, vA28-HAi, the A28L gene was modified to contain a bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase promoter with an adjacent Escherichia coli lac operator, and an influenza virus HA epitope tag. In addition, vA28-HAi encodes the E. coli lac repressor regulated by a vaccinia virus dual early-late promoter and the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase regulated by a vaccinia virus late promoter adjacent to an E. coli lac operator. In the absence of IPTG, the lac repressor is continuously made and inhibits expression of both the T7 RNA polymerase and the A28-HA protein providing stringent regulation. Consequently, plaque formation and the production of infectious vA28-HA were dependent on IPTG, which inactivates the repressor. Surprisingly, no defect in the processing of viral proteins or in the assembly of intracellular or extracellular virions could be discerned during a single round of infection in the absence of IPTG. However, since vA28-HAi must be propagated in the presence of IPTG, the IMV used to infect cells in the previous experiments contained A28-HA.

One interpretation of the above data was that A28 (or A28-HA) is required for infectivity of progeny virions. To test this, we purified IMV made in the presence or absence of IPTG. Sharp opalescent bands of virus were obtained in each case. Moreover, there was no apparent difference in the position, width or opacity of the viral bands derived from the two preparations. The material from each band was collected, and the optical density at 260 nm (OD260) was determined, yielding similar values. The samples were adjusted to the same OD260, and the infectivity was determined. The infectivity of the +A28-HA virions from cells infected with vA28-HAi in the presence of IPTG was ∼100 times greater than the infectivity of the −A28-HA virions from cells infected with vA28-HAi in the absence of IPTG, in good agreement with the 2-log difference in yields of infectious virus obtained in one-step growth experiments (44a). We determined that the very low infectivity of −A28-HA virions could be entirely accounted for by residual inoculum, which could not be removed by washing the cells after virus adsorption.

Morphology and polypeptide composition.

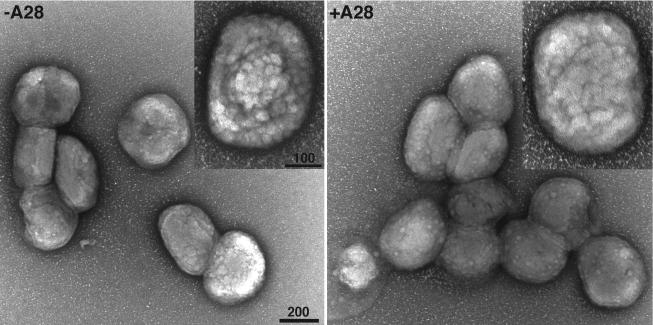

Sucrose gradient-purified preparations of −A28-HA and +A28-HA IMV were deposited on grids, negatively stained, and examined by electron microscopy. Both preparations contained virions with the characteristic oval shape and knobby appearance (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Morphology of purified +A28-HA (+A28) and −A28-HA (−A28) virions. Sucrose gradient-purified IMV were adsorbed to grids, washed with water, and stained with 7% uranyl acetate in 50% ethanol for 30 s. Bar, 200 nm.

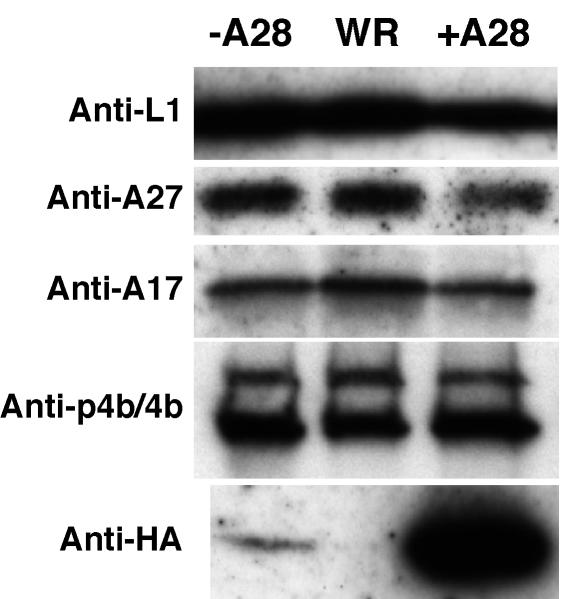

Since the expression of A28 (or A28-HA) was not required for assembly, intracellular movement, wrapping, or exocytosis of morphologically normal-looking virions, we anticipated that A28-deficient virions would contain the major vaccinia virus proteins. This was confirmed by analyzing the protein contents of wild-type WR, +A28-HA, and −A28-HA IMV by SDS-PAGE and silver staining (not shown). Representative viral proteins were identified by using specific antibodies. Three IMV membrane-associated proteins (L1, A27, and A17), as well as the processed core protein 4b, and small amounts of the p4b precursor were detected in the WR, −A28-HA, and +A28-HA IMV (Fig. 2). The only difference observed was in the amount of A28-HA. As expected, an intense A28-HA band was detected in +A28-HA virions by using the anti-influenza HA antibody, whereas no A28-HA was detected in the wild-type vaccinia virus WR and only a trace, consistent with the residual inoculum infectivity, was present in −A28-HA virions (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Western blot analysis of proteins from purified +A28-HA (+A28), −A28-HA (−A28), and wild-type (WR) virions. Equal OD260s of sucrose gradient-purified IMV were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies indicated on the left.

In vitro synthesis of RNA.

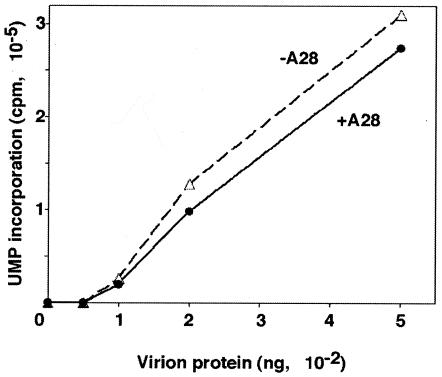

Infectious poxvirus particles contain a complete multicomponent system for RNA synthesis, which can be demonstrated by incubating the particles with ribonucleoside triphosphates in the presence of a nonionic detergent. This transcription system is activated when cores enter the cytoplasm and is responsible for synthesis of viral early mRNA. As a test of the functionality of purified −A28-HA virions, we compared their transcriptional activities with that of +A28-HA virions. RNA synthesis was proportional to virion protein added and was similar in magnitude for the two virus preparations (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional activity of purified +A28-HA (+A28) and −A28-HA (−A28) virions. Purified virions were incubated with nonionic detergent and ribonucleoside triphosphates, and the incorporation of [α-32P]UMP into RNA was determined. The amount of virion protein was determined from the OD260.

Cell binding and cytopathic effects.

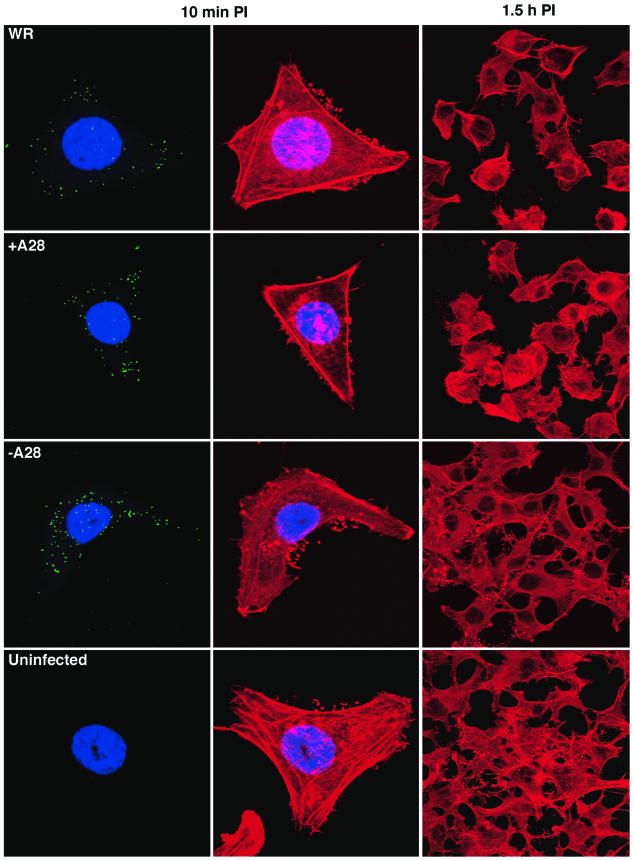

Next, we compared the abilities of −A28-HA and +A28-HA virions to bind to cells and induce morphological changes. Subconfluent HeLa cell monolayers on coverslips were inoculated with purified IMV at room temperature, which allows binding to cells but not penetration (9, 28). After 1 h, the cultures were washed and moved to a 37°C incubator, and individual monolayers were fixed at 10, 30, and 90 min. IMV on the surface of cells were detected by indirect immunofluorescence with an MAb to the L1 IMV surface protein, cellular actin filaments were visualized with Alexa fluor 568 phalloidin, and nuclei were stained with DAPI. The leftmost panels in Fig. 4 display punctate L1-staining IMV associated with cells infected with WR, +A28-HA, and −A28-HA virions, indicating that A28 was not required for binding. The middle panels show actin staining of the same cells. We noted slender actin protrusions similar to those previously described in infected cells (28) on the cells infected with all three viruses, as well as on uninfected cells. Differences between actin protrusions of uninfected and infected cells were also not discerned with higher multiplicities of virus or at 30 min after infection (not shown). At 30 min, however, the cells infected with WR or +A28-HA virions exhibited evidence of rounding, which was more pronounced at 1.5 h (Fig. 4, right panels). In contrast, cells inoculated with −A28-HA virions did not show cytopathic effects and resembled uninfected cells (Fig. 4, right panels). Cell rounding and associated cytopathic effects were previously reported to require viral protein synthesis (1). Similarly, we found that the cytopathic effect of +A28-HA virions did not occur in the presence of cycloheximide (data not shown).

FIG.4.

Binding and cytopathic effects produced by purified virions. Replicate HeLa cell monolayers on coverslips were infected with 10 PFU per cell of purified +A28-HA (+A28) or the equivalent OD260 of purified −A28-HA (−A28) virions. After 1 h of adsorption at room temperature, the cells were washed three times and incubated for 10 min, 30 min, or 1.5 h at 37°C. Cells were stained with anti-L1 mouse MAb, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue) and F actin with Alexa Fluor 568 phalloidin (red). For L1 staining, cells were imaged by confocal microscopy as a series of optical sections and are displayed here as a maximum-intensity projection. The left and middle panels of each row depict the same cell. For the low magnifications in the right panels, only Alexa Fluor 568 phalloidin staining is shown.

Virus penetration.

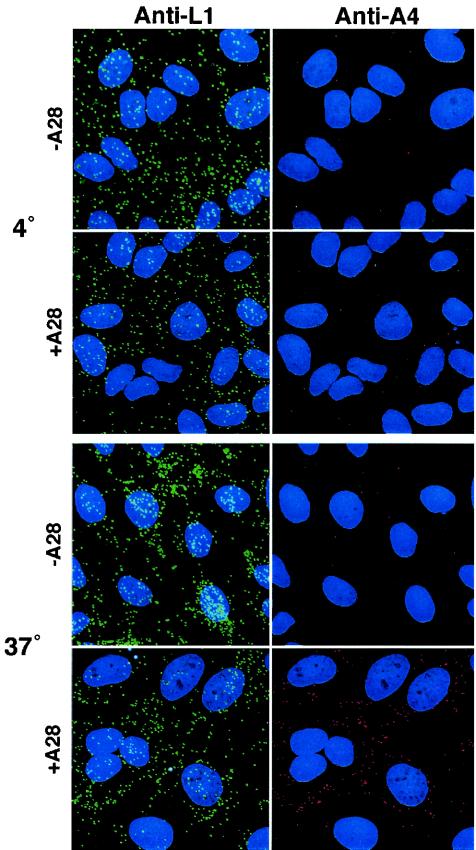

The ability of −A28-HA virions to bind to cells without inducing a cytopathic effect implied that gene expression had not occurred. Because A28-HA is localized to the surface of IMV, we considered that the block was probably at the stage of virus penetration. To investigate this possibility, we used an assay based on the ability of antibodies to core proteins to react with uncoated cores in the cytoplasm but not with membrane-enclosed cores on the surface of infected cells (28, 54). BS-C-1 cells were incubated with −A28-HA or +A28-HA virions at 4°C for 1 h to allow binding. The cells were washed and then either fixed and processed or incubated for an additional 2 h at 37°C in the continuous presence of cycloheximide, a protein synthesis inhibitor, to allow cores to penetrate and accumulate in the cytoplasm without undergoing secondary uncoating. To detect particles on the cell surface and penetrated cores, we used antibodies to the L1 membrane protein and to the A4 core protein, respectively. After incubation at 4°C, abundant −A28-HA and +A28-HA virions were visualized as punctate L1 antibody-staining particles on the cell surface, but few cores were detected with the A4 antibody (Fig. 5). After incubation at 37°C, many A4 antibody-staining cores were seen in cells infected with +A28-HA virions (Fig. 5). In cells infected with −A28-HA virions, however, the number of cores had not increased over the 4°C background (Fig. 5). The presence of −A28-HA virions on the cell surface but the absence of intracellular cores pinpointed the defect to the step of membrane uncoating and penetration.

FIG. 5.

Binding and penetration of cells by purified virions. Replicate HeLa cell monolayers on coverslips were infected with 10 PFU per cell of purified +A28-HA (+A28) or the equivalent OD260 of purified −A28-HA (−A28) virions in the presence of 300 μg of cycloheximide per ml. After 1 h of adsorption at 4°C, the cells were washed and either fixed or incubated further at 37°C for 2 h. Cells were double stained with anti-A4 rabbit polyclonal and anti-L1 mouse MAbs, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse (green) and Rhodamine Red-X-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (red) antibody, respectively. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Cells were imaged by confocal microscopy as a series of optical sections and are displayed here as a maximum-intensity projection.

Viral gene expression.

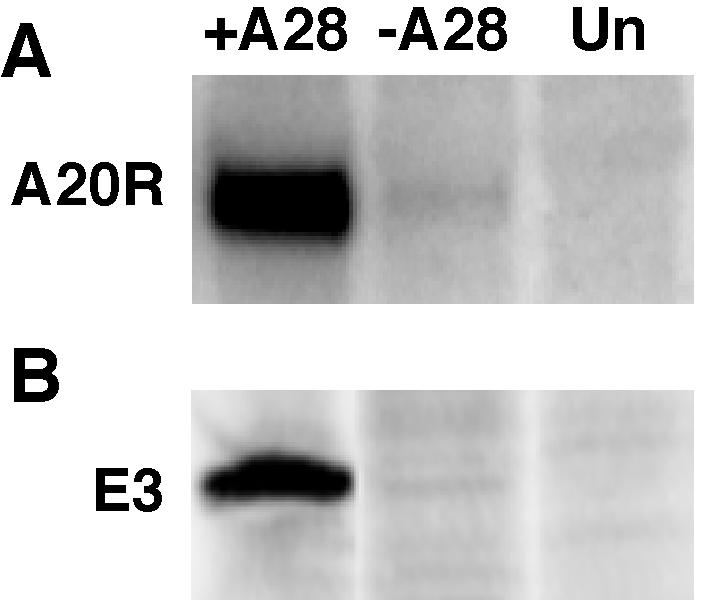

Viral RNA synthesis normally occurs soon after the penetration step because all of the necessary enzymes and factors are packaged in virus cores. In a previous section, we showed that purified −A28-HA virions were capable of RNA synthesis in vitro. Therefore, the measurement of early RNA synthesis in vivo provided a second way of determining whether −A28-HA cores penetrated into cells. Cells were infected in the presence of AraC with 10 PFU of purified +A28-HA virions per cell or with the equivalent amount of −A28-HA virions. RNA was extracted, fractionated by gel electrophoresis, transferred to a membrane, and hybridized to a radioactive probe corresponding to a representative early mRNA encoding the A20 DNA replication processivity factor (23). An intense band of the expected size was seen in RNA from cells infected with +A28-HA IMV, but only a trace was detected in RNA from cells infected with −A28-HA IMV (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Determination of early gene expression. (A) Early RNA. BS-C-1 cell monolayers were treated with AraC (40 μg/ml) for 2 h prior to infection with 5 PFU of purified +A28-HA (+A28) virions per cell, the equivalent OD260 of −A28-HA (−A28) virions, or mock infected (Un). Total RNA was extracted, resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon filter, probed with 32P-labeled plasmid containing the A20R early gene of vaccinia virus, and analyzed by autoradiography. (B) Cells were infected as in panel A, except that AraC was not added, and were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine from 2 to 5 h. Lysates were incubated with a MAb to the E3 protein and to protein A-beads. After the beads were washed, the bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

We also examined viral early protein synthesis by metabolically labeling infected cells with [35S]methionine and capturing the E3 early protein with a specific MAb (66). The bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography. An intense band of the expected size was detected in the material from cells infected with +A28-HA virions but not from cells infected with −A28-HA virions or mock-infected cells (Fig. 6B).

Virus-induced fusion from within and without.

Vaccinia virus can induce two types of low-pH-triggered cell fusion. Fusion from within occurs after brief low-pH exposure at late time after infection, when progeny virions are present on the cell surface (9, 12). Any treatment or viral mutation that prevents the formation of virions or their delivery to the cell surface also prevents acid-mediated cell fusion (3, 41, 62). The second type of fusion, called fusion from without, does not depend on de novo viral protein synthesis and occurs after cells are incubated in the presence of cycloheximide with large quantities of purified IMV and then are briefly exposed to acid pH (12). Although there is a clear relationship between fusion from within and without, a connection between either type of acid-mediated fusion and virus entry has not been established. We investigated such a connection by using the vA28-HAi recombinant virus.

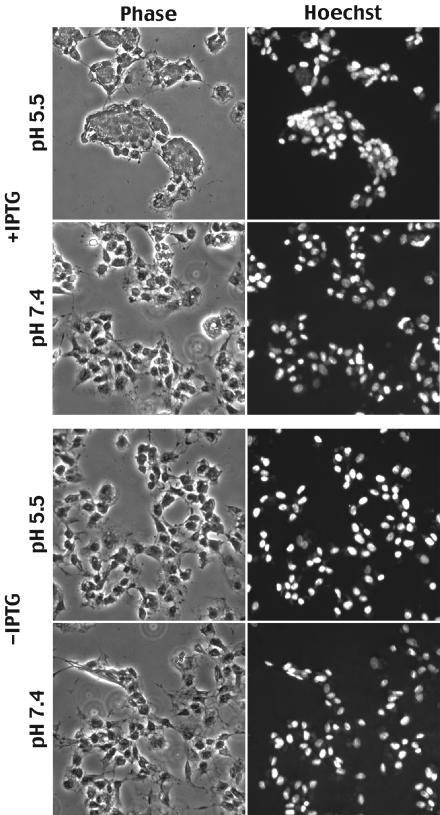

Based on the formation of cell surface virions (44a), we might expect fusion from within to occur in cells that were infected with vA28-HAi in the presence or absence of IPTG. However, this was not the case. Cells that were infected with vA28-HAi in the presence of IPTG, and which therefore expressed A28-HA, formed large syncytia after exposure to low pH (Fig. 7). As anticipated, replicate infected cells exposed to neutral pH showed vaccinia virus-induced cytopathic effects but no syncytia (Fig. 7). Importantly, no syncytia were seen in cells that had been infected with vA28-HAi in the absence of IPTG, which therefore did not express A28-HA, after either low- or neutral-pH exposure (Fig. 7). These results indicated that the process of fusion from within depends on expression of A28.

FIG. 7.

Fusion from within. BS-C-1 cell monolayers were infected with 5 PFU of vA28-HAi per cell in the presence (+) or absence (−) of IPTG for 18 h at 37°C. At that time, the medium was replaced with pH 7.4 or 5.5 buffer for 2 min at 37°C. The incubation was then continued in regular medium for 3 h at 37°C. The cells were fixed, stained with Hoechst reagent, and examined by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy.

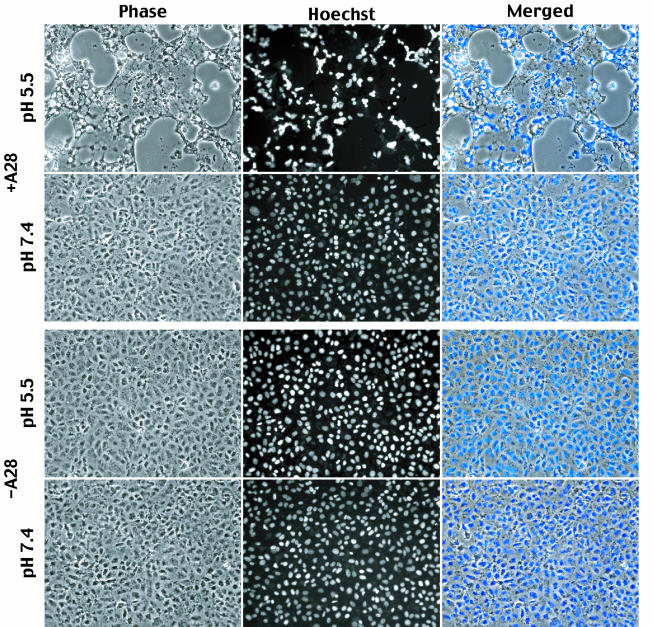

To measure fusion from without, cells were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with 200 PFU of purified +A28-HA IMV per cell or the same OD260 of −A28-HA IMV. Cycloheximide was added with the virus to block early cytopathic effects that might interfere with the fusion assay. The cells were then briefly exposed to low or neutral pH at 4°C, after which the temperature was raised to 37°C. Although there was extensive syncytium formation in the cultures that had been incubated with +A28-HA virions and exposed to low pH, no fusion was observed in cells that had been incubated at neutral pH (Fig. 8). Furthermore, no syncytia were detected in cells that had been incubated with −A28-HA virions, regardless of treatment (Fig. 8). Thus, A28 is required for vaccinia virus-induced fusion from within and without.

FIG. 8.

Fusion from without. BS-C-1 cell monolayers were incubated with 200 PFU of purified +A28-HA (+A28) virions per cell or the equivalent OD260 of purified −A28-HA- (−A28) virions. After 1 h of adsorption at 4°C, the cells were washed and then treated for 2 min with pH 7.4 or 5.5 buffer and then incubated in regular medium with 300 μg of cycloheximide per ml for 3 h at 37°. Cells were fixed, stained with Hoechst reagent, and examined by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy.

DISCUSSION

In a related study (44a), we demonstrated that repression of synthesis of the A28 IMV membrane protein inhibited the formation of virus plaques, as well as infectious particles. Nevertheless, all stages of virus assembly occurred normally, and intracellular and extracellular virion production was unimpaired. To determine the nature of the defect, we purified A28-deficient vaccinia virus particles and examined them microscopically and biochemically. The virions were indistinguishable from the wild type by electron microscopic appearance, analysis of virion proteins, or ability to synthesize RNA in vitro. Nevertheless, the A28-deficient virions were noninfectious. Because A28 is an IMV surface membrane protein, we considered that it was more likely to have a role in virus attachment or entry than on later events. However, numerous A28-deficient IMV were detected by confocal microscopy on the surface of cells, indicating that virion attachment does not depend on A28. This result was not surprising, as the initial association of IMV with the cell appears to occur through three IMV membrane proteins that bind cell surface glycosaminoglycans (7, 17, 26, 57). We strongly suspected, therefore, that the defect caused by the absence of A28 was in the penetration of cores into the cytoplasm. Indeed, cytoplasmic cores from A28-deficient virions were not detected by confocal microscopy using an antibody staining method developed by Vanderplasschen et al. (54). The inability to detect cores in the cytoplasm was almost certainly due to a block in entry. Although other explanations, such as failure of cytoplasmic cores to stain with the antibody to the A4 core protein or rapid degradation of cores, are possible, it is difficult to understand how the presence or absence of a membrane protein would cause such effects. In addition, the nearly total absence of expression of representative early genes was consistent with a block in virus entry. Although mutants that produce virions with diminished infectivity due to reduced cell binding (17, 26) or early transcription (27, 61, 67) have been described previously, vA28-HAi is the first mutant shown to have a block at the entry stage of infection.

Since it is generally believed that IMV enter cells by fusion with the plasma membrane or with vesicles formed by surface invagination, we investigated the role of A28 in vaccinia virus-induced, acid-triggered cell fusion. We found that A28 was required for fusion of cells at late times after infection (fusion from within), as well as fusion mediated by inoculating cells with large numbers of virions in the presence of cycloheximide (fusion from without). Although it seems likely that vaccinia virus-induced cell fusion mimics events occurring during virus entry, the need for a low-pH trigger remains unclear. The vaccinia virus IMV surface protein encoded by the A27L open reading frame, called p14 or fusion protein, has also been implicated in cell fusion (58), although a direct role seems unlikely as it lacks a transmembrane domain, which is a hallmark of other viral fusion proteins. Nevertheless, the following observations are consistent with an involvement of A27 in fusion (i) antibody against A27 neutralizes infectivity and inhibits fusion from within and without (12, 24, 38), (ii) repression of A27 expression inhibits fusion from within (16), (iii) A27-deficient virions exhibit reduced fusion from without (12, 57), and (iv) soluble A27 inhibits fusion from within (16). On the other hand, these effects may be indirect as A27 has a variety of other functions, including binding to cell surface glycosaminoglycans (16, 57), intracellular IMV movement (42), and formation of extracellular virions (39), each of which could affect fusion. An argument against A27 having an important role in entry and fusion is that A27-deficient IMV retain nearly complete (17, 39) or partial (57) infectivity. We have shown here that although A28-deficient virions contain normal amounts of A27, as well as its binding partner A17, they are unable to induce cell fusion. The L1 protein, thought to have a role in penetration based on the ability of a MAb to neutralize infectivity when added after the binding step (20, 64), was also shown to be present in A28-deficient virions. How A28 facilitates cell entry and fusion remains to be determined.

In summary, the analyses described here and elsewhere (44a) indicated that the A28 protein is not required for virion assembly, intracellular movement, wrapping, or exit from the cell. Even though A28-deficient IMV appear normal, they are noninfectious; they can bind to cells, but the cores cannot penetrate into the cytoplasm. The entry block was correlated with the inability of A28-deficient virions to mediate cell fusion, thus providing compelling evidence for an association between these events. Furthermore, because repression of A28 also inhibits cell-to-cell spread and plaque formation, which are mediated by extracellular virions, all forms of vaccinia virus regardless of their outer coat must use a common A28-dependent mechanism of cell penetration. Finally, since A28, as well as the redox proteins, needed to form the disulfide bonds of A28 are conserved, all poxviruses are likely to penetrate cells in the same way.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Weisberg for electron microscopy, Norman Cooper for maintenance of cell lines, and Mariano Esteban and Alan Schmaljohn for antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bablanian, R., B. Baxt, J. A. Sonnabend, and M. Esteban. 1978. Studies on the mechanisms of vaccinia virus cytopathic effects. II. Early cell rounding is associated with virus polypeptide synthesis. J. Gen. Virol. 39:403-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betakova, T., E. J. Wolffe, and B. Moss. 1999. Regulation of vaccinia virus morphogenesis: phosphorylation of the A14L and A17L membrane proteins and C-terminal truncation of the A17L protein are dependent on the F10L protein kinase. J. Virol. 73:3534-3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasco, R., and B. Moss. 1991. Extracellular vaccinia virus formation and cell-to-cell virus transmission are prevented by deletion of the gene encoding the 37, 000 Dalton outer envelope protein. J. Virol. 65:5910-5920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blasco, R., and B. Moss. 1992. Role of cell-associated enveloped vaccinia virus in cell-to-cell spread. J. Virol. 66:4170-4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulter, E. A., and G. Appleyard. 1973. Differences between extracellular and intracellular forms of poxvirus and their implications. Prog. Med. Virol. 16:86-108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, A., and D. H. Metz. 1976. Further investigations on the mode of entry of vaccinia virus into cells. J. Gen. Virol. 32:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung, C.-S., J.-C. Hsiao, Y.-S. Chang, and W. Chang. 1998. A27L protein mediates vaccinia virus interaction with cell surface heparin sulfate. J. Virol. 72:1577-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demkowicz, W. E., J. S. Maa, and M. Esteban. 1992. Identification and characterization of vaccinia virus genes encoding proteins that are highly antigenic in animals and are immunodominant in vaccinated humans. J. Virol. 66:386-398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doms, R. W., R. Blumenthal, and B. Moss. 1990. Fusion of intra- and extracellular forms of vaccinia virus with the cell membrane. J. Virol. 64:4884-4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earl, P. L., B. Moss, L. S. Wyatt, and M. W. Carroll. 1998. Generation of recombinant vaccinia viruses, p. 16.17.1-16.17.19. In F. M. Ausubel, R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology, vol. 2. Greene Publishing Associates & Wiley Interscience, New York, N.Y.

- 11.Geada, M. M., I. Galindo, M. M. Lorenzo, B. Perdiguero, and R. Blasco. 2001. Movements of vaccinia virus intracellular enveloped virions with GFP tagged to the F13L envelope protein. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2747-2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong, S. C., C. F. Lai, and M. Esteban. 1990. Vaccinia virus induces cell fusion at acid pH and this activity is mediated by the N terminus of the 14-kDa virus envelope protein. Virology 178:81-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiller, G., and K. Weber. 1985. Golgi-derived membranes that contain an acylated viral polypeptide are used for vaccinia virus envelopment. J. Virol. 55:651-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollinshead, M., G. Rodger, H. Van Eijl, M. Law, R. Hollinshead, D. J. Vaux, and G. L. Smith. 2001. Vaccinia virus utilizes microtubules for movement to the cell surface. J. Cell Biol. 154:389-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollinshead, M., A. Vanderplasschen, G. L. Smith, and D. J. Vaux. 1999. Vaccinia virus intracellular mature virions contain only one lipid membrane. J. Virol. 73:1503-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsiao, J.-C., C.-S. Chung, and W. Chang. 1998. Cell surface proteoglycans are necessary for A27L protein-mediated cell fusion: identification of the N-terminal region of A27L protein as the glycosaminoglycan-binding domain. J. Virol. 72:8374-8379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiao, J.-C., C.-S. Chung, and W. Chang. 1999. Vaccinia virus envelope D8L protein binds to cell surface chondroitin sulfate and mediates the adsorption of intracellular mature virions to cells. J. Virol. 73:8750-8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ichihashi, Y. 1996. Extracellular enveloped vaccinia virus escapes neutralization. Virology 217:478-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ichihashi, Y., and M. Oie. 1983. The activation of vaccinia virus infectivity by the transfer of phosphatidylserine from the plasma membrane. Virology 130:306-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichihashi, Y., and M. Oie. 1996. Neutralizing epitopes on penetration protein of vaccinia virus. Virology 220:491-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ichihashi, Y., and M. Oie. 1982. Proteolytic activation of vaccinia virus for penetration phase of infection. Virology 116:297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janeczko, R. A., J. F. Rodriguez, and M. Esteban. 1987. Studies on the mechanism of entry of vaccinia virus into animal cells. Arch. Virol. 92:135-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemperer, N., W. McDonald, K. Boyle, B. Unger, and P. Traktman. 2001. The A20R protein is a stoichiometric component of the processive form of vaccinia virus DNA polymerase. J. Virol. 75:12298-12307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai, C. F., S. C. Gong, and M. Esteban. 1991. The purified 14-kilodalton envelope protein of vaccinia virus produced in Escherichia coli Induces virus immunity in animals. J. Virol. 65:5631-5635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law, K. M., and G. L. Smith. 1992. A vaccinia serine protease inhibitor which prevents virus-induced cell fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 73:549-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin, C. L., C. S. Chung, H. G. Heine, and W. Chang. 2000. Vaccinia virus envelope H3L protein binds to cell surface heparan sulfate and is important for intracellular mature virion morphogenesis and virus infection in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 74:3353-3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, K., B. Lemon, and P. Traktman. 1995. The dual-specificity phosphatase encoded by vaccinia virus, VH1, is essential for viral transcription in vivo and in vitro. J. Virol. 69:7823-7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Locker, J. K., A. Kuehn, S. Schleich, G. Rutter, H. Hohenberg, R. Wepf, and G. Griffiths. 2000. Entry of the two infectious forms of vaccinia virus at the plasma membane is signaling-dependent for the IMV but not the EEV. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:2497-2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meiser, A., C. Sancho, and J. Krijnse Locker. 2003. Plasma membrane budding as an alternative release mechanism of the extracellular enveloped form of vaccinia virus from HeLa cells. J. Virol. 77:9931-9942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss, B. 2001. Poxviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 2849-2883. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott/The Williams & Wilkins Co., Philadelphia, Pa.

- 31.Payne, L. 1978. Polypeptide composition of extracellular enveloped vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 27:28-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravanello, M. P., C. A. Franke, and D. E. Hruby. 1993. An NH2-terminal peptide from the vaccinia virus L1R protein directs the myristylation and virion envelope localization of a heterologous fusion protein. J. Biol. Chem. 268:7585-7593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ravanello, M. P., and D. E. Hruby. 1994. Conditional lethal expression of the vaccinia virus L1R myristylated protein reveals a role in virus assembly. J. Virol. 68:6401-6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rietdorf, J., A. Ploubidou, I. Reckmann, A. Holmström, F. Frischknecht, M. Zettl, T. Zimmerman, and M. Way. 2001. Kinesin-dependent movement on microtubules precedes actin based motility of vaccinia virus. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:992-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Risco, C., J. R. Rodriguez, C. Lopez-Iglesias, J. L. Carrascosa, M. Esteban, and D. Rodriguez. 2002. Endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment membranes and vimentin filaments participate in vaccinia virus assembly. J. Virol. 76:1839-1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodríguez, D., M. Esteban, and J. R. Rodríguez. 1995. Vaccinia virus A17L gene product is essential for an early step in virion morphogenesis. J. Virol. 69:4640-4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez, J. F., and M. Esteban. 1987. Mapping and nucleotide sequence of the vaccinia virus gene that encodes a 14-kilodalton fusion protein. J. Virol. 61:3550-3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez, J. F., R. Janeczko, and M. Esteban. 1985. Isolation and characterization of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 56:482-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez, J. F., and G. L. Smith. 1990. IPTG-dependent vaccinia virus: identification of a virus protein enabling virion envelopment by Golgi membrane and egress. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5347-5351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez, J. R., C. Risco, J. L. Carrascosa, M. Esteban, and D. Rodriguez. 1998. Vaccinia virus 15-kilodalton (A14L) protein is essential for assembly and attachment of viral crescents to virosomes. J. Virol. 72:1287-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanderson, C. M., F. Frischknecht, M. Way, M. Hollinshead, and G. L. Smith. 1998. Roles of vaccinia virus EEV-specific proteins in intracellular actin tail formation and low pH-induced cell-cell fusion. J. Gen. Virol. 79:1415-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanderson, C. M., M. Hollinshead, and G. L. Smith. 2000. The vaccinia virus A27L protein is needed for the microtubule-dependent transport of intracellular mature virus particles. J. Gen. Virol. 81:47-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmelz, M., B. Sodeik, M. Ericsson, E. J. Wolffe, H. Shida, G. Hiller, and G. Griffiths. 1994. Assembly of vaccinia virus: the second wrapping cisterna is derived from the trans-Golgi network. J. Virol. 68:130-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seki, M., M. Oie, Y. Ichihashi, and H. Shida. 1990. Hemadsorption and fusion inhibition activities of hemagglutinin analyzed by vaccinia virus mutants. Virology 175:372-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44a.Senkevich, T. G., B. M. Ward, and B. Moss. 2004. Vaccinia virus A28L gene encodes an essential protein component of the virion membrane with intramolecular disulfide bonds formed by the viral cytoplasmic redox pathway. J. Virol. 78:2348-2356 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Senkevich, T., C. White, A. Weisberg, J. Granek, E. Wolffe, E. Koonin, and B. Moss. 2002. Expression of the vaccinia virus A2.5L redox protein Is required for virion morphogenesis. Virology 300:296-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senkevich, T. G., A. Weisberg, and B. Moss. 2000. Vaccinia virus E10R protein is associated with the membranes of intracellular mature virions and has a role in morphogenesis. Virology 278:244-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Senkevich, T. G., C. L. White, E. V. Koonin, and B. Moss. 2002. Complete pathway for protein disulfide bond formation encoded by poxviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6667-6672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sodeik, B., R. W. Doms, M. Ericsson, G. Hiller, C. E. Machamer, W. van't Hof, G. van Meer, B. Moss, and G. Griffiths. 1993. Assembly of vaccinia virus: role of the intermediate compartment between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi stacks. J. Cell Biol. 121:521-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stokes, G. V. 1976. High-voltage electron microscope study of the release of vaccinia virus from whole cells. J. Virol. 18:636-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tooze, J., M. Hollinshead, B. Reis, K. Radsak, and H. Kern. 1993. Progeny vaccinia and human cytomegalovirus particles utilize early endosomal cisternae for their envelopes. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 60:163-178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Traktman, P., K. Liu, J. DeMasi, R. Rollins, S. Jesty, and B. Unger. 2000. Elucidating the essential role of the A14 phosphoprotein in vaccinia virus morphogenesis: construction and characterization of a tetracycline-inducible recombinant. J. Virol. 74:3682-3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsutsui, K. 1983. Release of vaccinia virus from FL cells infected with the IHD-W strain. J. Electron Microsc. 32:125-140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner, P. C., and R. W. Moyer. 1995. Orthopoxvirus fusion inhibitor glycoprotein SPI-3 (open reading frame K2L) contains motifs characteristic of serine protease inhibitors that are not required for control of cell fusion. J. Virol. 69:5978-5987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vanderplasschen, A., M. Hollinshead, and G. L. Smith. 1998. Intracellular and extracellular vaccinia virions enter cells by dfiferent mechanisms. J. Gen. Virol. 79:877-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vanderplasschen, A., and G. L. Smith. 1997. A novel virus binding assay using confocal microscopy: demonstration that intracellular and extracellular vaccinia virions bind to different cellular receptors. J. Virol. 71:4032-4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vanderplasschen, A., and G. L. Smith. 1999. Using confocal microscopy to study virus binding and entry into cells. Methods Enzymol. 307:591-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vazquez, M. I., and M. Esteban. 1999. Identification of functional domains in the 14-kilodalton envelope protein (A27L) of vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 73:9098-9109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vázquez, M. I., G. Rivas, D. Cregut, L. Serrano, and M. Esteban. 1998. The vaccinia virus 14-kilodalton (A27L) fusion protein forms a triple coiled-coil structure and interacts with the 21-kilodalton (A17L) virus membrane protein through a C-terminal α-helix. J. Virol. 72:10126-10137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ward, B. M., and B. Moss. 2001. Vaccinia virus intracellular movement is associated with microtubules and independent of actin tails. J. Virol. 75:11651-11663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ward, B. M., and B. Moss. 2001. Visualization of intracellular movement of vaccinia virus virions containing a green fluorescent protein-B5R membrane protein chimera. J. Virol. 75:4802-4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilcock, D., and G. L. Smith. 1996. Vaccinia virions lacking core protein VP8 are deficient in early transcription. J. Virol. 70:934-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolffe, E. J., S. N. Isaacs, and B. Moss. 1993. Deletion of the vaccinia virus B5R gene encoding a 42-kilodalton membrane glycoprotein inhibits extracellular virus envelope formation and dissemination. J. Virol. 67:4732-4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolffe, E. J., D. M. Moore, P. J. Peters, and B. Moss. 1996. Vaccinia virus A17L open reading frame encodes an essential component of nascent viral membranes that is required to initiate morphogenesis. J. Virol. 70:2797-2808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolffe, E. J., S. Vijaya, and B. Moss. 1995. A myristylated membrane protein encoded by the vaccinia virus L1R open reading frame is the target of potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Virology 211:53-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yeh, W. W., B. Moss, and E. J. Wolffe. 2000. The vaccinia virus A9 gene encodes a membrane protein required for an early step in virion morphogenesis. J. Virol. 74:9701-9711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yuwen, H., J. H. Cox, J. W. Yewdell, J. R. Bennink, and B. Moss. 1993. Nuclear localization of a double-stranded RNA-binding protein encoded by the vaccinia virus E3l gene. Virology 195:732-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang, Y., B.-Y. Ahn, and B. Moss. 1994. Targeting of a multicomponent transcription apparatus into assembling vaccinia virus particles requires RAP94, an RNA polymerase-associated protein. J. Virol. 68:1360-1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou, J., X. Y. Sun, G. J. P. Fernando, and I. H. Frazer. 1992. The vaccinia virus K2L gene encodes a serine protease inhibitor which inhibits cell-cell fusion. Virology 189:678-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]