Abstract

With advances in HIV treatment, more individuals have grown older with the disease. Little is known about factors that have helped these survivors manage everyday life with HIV. In this exploratory, qualitative study, we asked, What has helped survivors cope with challenges of living long-term with HIV? Participants were recruited from a convenience sample of persons living with HIV (PLWH) who obtained treatment at a specialty HIV clinic; 16 long-term survivors of HIV were interviewed. Mean age was 50.13 (SD = 8.30) years; mean time from diagnosis was 16.75 (SD = 5.98) years. Results were broadly dichotomized as coping mechanisms and social supports. Three themes characterized coping mechanisms: disease coping, practical coping, and emotional coping. Social supports included themes of family, friends, professionals, peer groups, and pets. In particular, the power of patient-professional relationships and meanings derived from religion/spirituality were considered influential factors by a majority of participants.

Keywords: coping, HIV, older adults, strengths perspective

As the U.S. population ages, the management of both physical and psychosocial aspects of chronic disease has become a necessary focus in primary medical and nursing care of patients. While research on the psychosocial aspects of chronic illness has often focused on pathologic correlates of disease, such as stress and depression, increasing attention is being paid to positive influences affecting individuals’ abilities to enhance well-being and cope effectively with illness. Factors associated with concepts of positive psychology, constructive emotions, and beneficial character traits have been shown to increase well-being, decrease depression, and promote long-term coping abilities (Frederickson & Joiner, 2002; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). The identification of positive influences on health is especially relevant for optimizing health care for the growing population of persons living with HIV (PLWH) who are subject to multiple risks related to aging, vulnerability, and chronic disease.

By 2005, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008) estimated that 15% of new cases of HIV and 24% of PLWH were adults ages 50 and older. As survival with HIV continues to improve, primary care has increased efforts to keep older adults with HIV healthy and functional in the face of co-morbidities that increase with age, such as hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes (Vance, 2010; Vance, Mugavero, Willig, Raper, & Saag, 2011). The role of medication advances in prolonging survival of PLWH is widely acknowledged. But little is known about how positive traits and resources of individuals and their environments may have contributed to coping and survival with HIV over the long term. Information from long-term survivors may suggest approaches to help support all PLWH, but especially younger and newly-diagnosed patients who lack the experience of having learned to live with HIV and chronic illness.

A number of positive traits and resources have been studied in HIV populations. Spirituality has been positively related to coping with HIV and quality of life (Tuck, McCain, & Elswick, 2001) as well as with reduction of HIV sexual risk behaviors (Wutoh et al., 2011). Individuals’ views of God as benevolent and forgiving have predicted slower HIV disease progression (Ironson et al., 2011), and spirituality also has been identified as a resource for overcoming challenges of HIV and aging (Vance, Brennan, Enah, Smith, & Kaur, 2011). Other factors associated with well-being of PLWH include abilities to adjust to change and view life situations positively (Dibb & Kamalesh, 2012), strengths related to a concept of resilience (Emlet, Tozay, & Raveis, 2011), and factors indirectly related to psychological well-being, such as employment status (Rueda et al., 2011). Lack of social support has been identified as a factor associated with HIV disease progression (Leserman et al., 2002), while the availability of social support has been shown to decrease distress and increase the well-being of older men with HIV (Chesney, Chambers, Taylor, & Johnson, 2003).

While a concept of coping and its measures have been used in various contexts of coping, such as coping styles, strategies, and skills (Harding, Liu, Catalan, & Sherr, 2011), we use the term broadly to focus on positive aspects of dealing with HIV. In a review article, Ironson and Hayward (2008) examined evidence for the relationship between HIV disease progression and positive psychological constructs that included beliefs, positive affect, behaviors, personality dispositions, and social support. Because psychosocial factors have been linked to biological correlates of HIV disease progression (Ironson et al., 2005; Leserman et al., 2002), the identification and maximization of positive psychosocial traits and social supports may provide additional tools for promoting the overall health of older persons with HIV. Our study elicited known and unknown positive traits and coping resources of long-term survivors of HIV. The research question asked what has helped HIV survivors to cope with the challenges of living long-term with HIV.

Methods

Design, Population, and Data Collection Procedures

In this exploratory, qualitative study, we conducted 16 semi-structured, in-depth interviews with HIV-infected individuals older than 21 years of age, who had been diagnosed for 5 years or more. We chose 5 years since diagnosis as the minimum cut-off for recruitment because we believed 5 years would provide a sufficient length of time for an individual to deal with adjustment to an HIV diagnosis in an era of effective treatment. At the same time, we were also interested in those who had been living with HIV for a longer period (i.e., 15-20 years), and who would have experienced changes in treatment and in the nature of the epidemic over past decades. These changes included uncertainties derived from a time of no effective treatment to the approval of azidothymidine (AZT) in 1987, through the complex and burdensome use of the initial protease inhibitors in the mid-nineties, and the more recent development of other classes of antiretroviral therapy and combination treatment in co-formulated tablets that decrease the pill burden. We chose not to use cut-off points such as the timing of advancements in HIV medications because we were interested in all ways of coping within a more present-oriented context, as well as within the past historical context.

During February and March 2011, a convenience sample of participants who received health care at a clinic specializing in the care of patients with HIV was recruited through clinician referral, posted flyers, and word-of-mouth. Interviews took place on-site in a private room. Participants were interviewed once, immediately after enrollment, if available, or at an appointment made for a future date. Interviews lasting 40-60 minutes were conducted, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Participants received a $30 gift card as compensation. The University Hospitals Case Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study. All participants signed the informed consent before the interview.

Using standard qualitative interview methods (Patton, 2002), general information about coping strategies was elicited, leading to specific explorations of coping with social relationships, taking HIV medications, and lifestyle changes. Interview guide questions focused on what challenges individuals had encountered in managing their HIV, what helped them through difficult periods, and how they coped with the disease on a daily and long-term basis.

Quality and credibility of data were obtained with standard qualitative techniques described by Patton (2002). To enhance quality of data, an interview guide was used together with informal questions. Recordings of interviews were continuously monitored for effective interaction processes, quality of questions, methods of asking, and missing information. Prompt questions (e.g., Can you say more about that?) were used to obtain elaboration of answers and to explore new themes. Contextual observations were noted; statements or conversations that were outside of the study aims were redirected. For consistency, a single investigator (JS), who is a nurse and cultural anthropologist, and who has conducted prior research with persons with or at risk for HIV, interviewed all participants.

Credibility, or trustworthiness of data, was obtained by crosschecking information within and across interviews, checking information with other data sources when available, and assessing the context of the information provided (e.g., assessing why the person was providing a specific kind of information). Personal reactions and reflections were identified and monitored, and their roles in interpreting the data were assessed. Theme saturation was reached with 16 participants. All participants were offered the opportunity to review the transcribed interview for accuracy and completeness; none chose to do so.

Data Analysis

Transcriptions were checked for accuracy and analyzed using continuous conventional content analysis in which themes emerged from the data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). A single investigator (JS) initially coded the data. Discrete topics were identified in transcription texts and assigned a code. Recurrent codes and similar topical patterns were organized into sub-themes, and then categorized into larger themes and configurations. ATLAS.ti software was used for data management, including quantification of code appearances in transcription texts, and grouping of related codes into larger themes or families (ATLAS.ti: the Qualitative Data Analysis & Research Software, 2002-2012). A final comprehensive review for competing or alternate interpretations (Barbour, 2001) was conducted by a second investigator (JL), who was also experienced in qualitative methodology. Our use of a single primary coder and a final comprehensive reviewer is consistent with Barbour (2001) who suggested that use of multiple coders did not necessarily improve rigor in qualitative research. She suggested that content of disagreements and insights for refining coding frameworks were more important than that of concordance in coding among researchers. All investigators contributed to interpretation of the data. Few differences in interpretations were noted; the co-investigators discussed these to obtain consensus.

Results

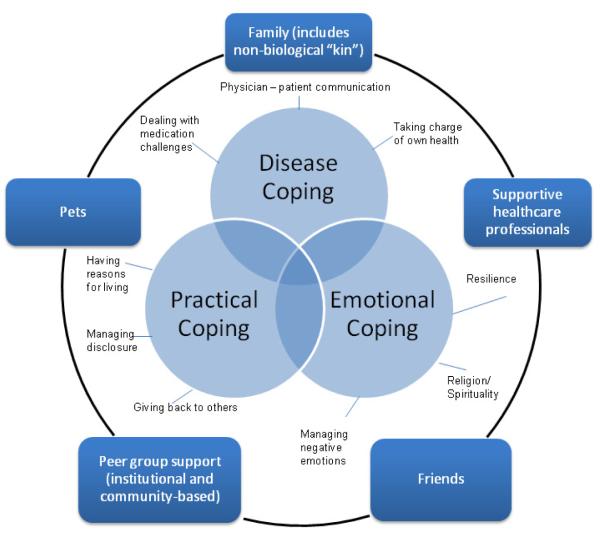

Demographic characteristics of participants are listed in Table 1. Our sample was 81% male, 19% female, with a mean age of 50.13 (SD = 8.30) and average of 16.75 years (SD = 5.98) since a diagnosis of HIV. We organized responses into two broad areas of coping mechanisms and social supports. The area of coping mechanisms was further subdivided into categories of disease coping, practical coping, and emotional coping, each with major themes. For the category of social supports, we identified five themes (family, friends, health professionals, community/support groups, and pets), which participants viewed as beneficial to their abilities to cope with their HIV (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Population (N = 16)

| Age in years | M = 50.13, SD = 8.30 | Range = 38 to 67 |

|

| ||

| Years of schooling | M = 14.25, SD = 2.72 | Range = 10 to 22 |

|

| ||

| Years since HIV diagnosis | M = 16.75, SD = 5.98 | Range = 8 to 26 |

|

| ||

| N | % | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| • Male | 13 | 81 |

| • Female | 3 | 19 |

|

| ||

| Marital Status | ||

| • Single | 11 | 69 |

| • Married or in a relationship | 4 | 25 |

| • Separated or divorced | 1 | 6 |

|

| ||

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| • Heterosexual | 3 | 19 |

| • Homosexual | 11 | 69 |

| • Bisexual | 1 | 6 |

| • Not disclosed | 1 | 6 |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| • White | 7 | 44 |

| • Black | 8 | 50 |

| • Hispanic | 1 | 6 |

|

| ||

| Work Situation | ||

| • Regular full-time work | 4 | 25 |

| • Regular part-time work | 1 | 6 |

| • Unemployed | 2 | 13 |

| • Disabled | 7 | 44 |

| • Other | 2 | 13 |

|

| ||

| Monthly Income | ||

| • Less than $100 | 1 | 6 |

| • $501 to $1000 | 4 | 25 |

| • $1001 to $1500 | 7 | 44 |

| • $1501 to $2999 | 3 | 19 |

| • $3000 or more | 1 | 6 |

|

| ||

| Major Source of Income | ||

| • Job | 4 | 25 |

| • Disability | 9 | 50 |

| • Retirement | 3 | 25 |

|

| ||

| Health Status | ||

| • Excellent | 3 | 19 |

| • Good | 10 | 63 |

| • Fair | 2 | 13 |

| • Poor | 1 | 6 |

Figure 1.

Positive coping with HIV within a supportive social environment.

Disease Coping

In disease coping (i.e., dealing with medical/physiological aspects of HIV), three major themes emerged: (a) ability to deal with challenges of taking medication for HIV, (b) development of a therapeutic relationship through effective professional-patient communication, and (c) taking charge of one’s own health. In living long-term with HIV, participants noted that the disease itself presented challenges, particularly in regard to taking medications. Before the development of newer HIV drugs with more convenient dosing schedules, taking HIV medications was complicated for some individuals by privacy concerns and/or by work schedules that necessitated travel. For example, if a participant were visiting family or working with colleagues who were unaware that the person was infected with HIV, the participant had to develop a strategy for taking a large number of pills everyday out of sight of other people. Or a person who was traveling might not be able to find refrigeration in a hotel room, if a drug required refrigeration.

Coping with HIV meant learning first-hand about HIV medicines and how they could affect the body and the disease process. Some participants were not currently taking HIV medications, and some had taken them from the beginning of the development of antiretroviral drugs, experiencing the extreme burdens of taking these early drugs. Others had started medication only after the newer and better drugs were developed. One participant noted that the development of new medications had given him hope for survival. But his better health also led him to stop taking his medications. He experienced an exacerbation, an event that presumably provided him with insight into the need for adherence. Another person, when asked about his experience with HIV medications, summarized by saying:

… Sometimes I’m healthy with tons of energy, and sometimes I’m just exhausted and can barely work up enough strength to do normal day-to-day things. So it kind of comes and goes. The medicines do affect … They’re highly toxic. They do affect your metabolism. Your body changes. You get fat where you used to be thin. You get thin where you used to be normally healthy. It affects your digestion. It basically affects every aspect of your life, so it’s kind of learning to deal with the effects that occur throughout the entire process of the illness.

Closely tied to dealing with medication challenges was having a physician with whom one could communicate one’s needs. Participants noted that good physician-patient communication was useful in finding the right drug or drug combination that would control the disease, minimize side effects, and provide a dosing schedule compatible with one’s lifestyle. One individual explained:

You know like I said, we sat down and we (the doctor and I) had talked about what I need to do and I told him I need something really that’s not as hard for me to work on that I know that I would take on a regular basis. So we both sat down and came up with this group of medicines that I knew I could stick to and commit to just for my health to make me be able to live longer and made more tolerable and easier for me to remember….

In addition to dealing with medication challenges and engaging in effective communication with physicians, many participants coped by taking charge of their health, through learning about HIV, self-managing aspects of the illness, and striving for a healthy lifestyle. Not everyone achieved success in meeting their personal health care goals, but most individuals were aware of behaviors needed to maintain a healthy lifestyle. As one participant said,

So I know I’m doing everything I possibly can do, getting the blood work. I’m on the meds. That in itself is a comfort, knowing that I’m doing everything I possibly can do to make sure that I am healthy …

In general, coping with the disease-related challenges of HIV were characterized by participants managing medication issues, maintaining a therapeutic relationship through communication with health care providers, and taking an active role in their health care.

Practical Coping

We refer to practical coping as an ability to cope with everyday demands of life with HIV. Practical coping was associated with having a reason for living, managing disclosure of HIV status, and a responsibility to give back to others. Reasons for living were described by some participants and included becoming the primary caregiver for a child or grandchild, and a desire to live to see their children finish their education or achieve adulthood. As some participants grew older with HIV, grandchildren became a focus in their lives. One participant said,

I believe God wants me here for some reason. When it happened (i.e., when this person was diagnosed), the only thing I asked for was to see my kids grow up, graduate high school, and I’m done. But now I get to see two grandkids.

For most participants, children, grandchildren, interactions with spouses or partners, close friends, a meaningful employment situation, or even pets provided a will and reason to live.

Another aspect of practical coping was managing disclosure of one’s HIV status. Some participants were unwilling to share the diagnosis with anyone, except a partner or spouse, while others were comfortable being completely open and public about their HIV status. Most participants were in-between, disclosing to some individuals and not to others, or identifying individuals they believed had a need to know:

I didn’t feel that I really needed to tell (family). Not that I don’t think they wouldn’t have loved me or hated me, you know, either way, but I just didn’t feel like it was anything I needed to put on them. Again, the same with my friends, so I was just a healthy, to me I was a healthy individual leading a normal life but with HIV. So I didn’t feel that they needed to know, but when it hit me that “This is real,” I thought “Well somebody should know,” you know, so I had told (a family member) so somebody in the family knew, would know if something ever happened to me…

Reactions to disclosure of one’s HIV status were varied. Participants sometimes faced rejection from family and/or friends, while some relatives and friends were accepting, or became supportive after initial rejection. Disclosure to children was often difficult, especially in the case of younger children, when the HIV-infected parent had to decide whether to disclose and if so, at what age to tell the child. Participants expressed a responsibility for honest disclosure if someone (e.g., a significant other) needed to know their HIV status.

Another theme of practical coping was a desire to give back to others. Reasons for giving back included the desire to teach and warn others about contracting HIV and/or about coping with it, gratitude for the help participants had received from others, and fulfillment of a responsibility to cherish life in memory of those who had not survived.

Emotional Coping

We categorized emotional coping as having three primary themes: (a) resilience in overcoming challenges associated with HIV; (b) ability to manage negative emotions, often by thinking positively; and (c) reliance on religion/spirituality for support. Participants’ resilience in dealing with adversity related to HIV was evident in most interviews. An unexpected HIV diagnosis is devastating for individuals, but it was especially so for those diagnosed in the early years when knowledge was limited and effective treatments were not yet developed. For these participants, survival was an unexpected outcome that necessitated a change in one’s perspective on life. In addition to coping with a serious and stigmatized disease, many long-term survivors had experienced the deaths of loved ones from HIV. Most participants described eventually coming to terms with HIV as a chronic, rather than terminal, illness, thinking of it “only when taking medications,” as “second nature,” or as comparable to living with other chronic diseases. As one participant said, “I don’t define myself by being infected with HIV. It’s just a part of who I am.” In addition to resilience, participants often exhibited a tendency to deal with negative feelings or situations by reframing them positively, or “letting go,” or moving past these feelings. One individual described his continued survival:

… and I came to acknowledge the fact that there had to be another reason for me to be around, so that’s the reason that my attitude changed and I let go of a lot of the anger. I still get angry about it sometimes. I still get frustrated with having to take the medications. I still have all the feelings that most people would have, and the thing is, but the thing is though, I’ve learned to get past it and know that it’s just for a minute. Everything is only for a while and it doesn’t last forever. So I move on and I let go.

A majority of participants attributed a large part of their health and ability to cope with challenges of living with HIV to religious and/or spiritual beliefs. Faith, prayer, and spirituality were seen as helping with physical and emotional healing, especially during an illness crisis. Beliefs based on faith or spiritual traditions were seen by one participant as helpful in changing deleterious behaviors, such as drug use. Some individuals participated in organized religion without disclosing private aspects of their lives. For others, spirituality was embraced when formal religion was rejected due to non-tolerance of an alternative lifestyle. Or an individual might have sought out a specific religious denomination or congregation that accepted diverse lifestyles because of a desire for formal religious involvement or to raise one’s child in a religious tradition. Some participants held spiritual beliefs, but were not necessarily engaged in organized religion. This participant’s comment exemplified the distinction some individuals made between formal religion and spirituality:

Let me get this straight. Let me clarify. I’m (religious denomination). I was raised (religious denomination); grew up in the church to some extent. I don’t go to church regularly probably like I should, but I do believe in God. I do pray a lot, and whatever or whoever, whatever force is out there, God or what anybody else chooses to call it, does manage to send me answers to the questions that I ask and resolutions to the problems that I have. They may not be the ones that I always want, but they’re most of the things that I have to deal with and contend with are answered and dealt with, and it has absolutely nothing to do with me on a lot of accounts.

For a few participants, long-term survival meant a spiritual bond with those who did not survive and a responsibility, in a sense, to live life fully for those who died:

…in regards to how I deal with losing friends and losing people I know to this disease, then I like to think that I keep going partially for me, but partially for them too. So I don’t know how long I’ll be around, but as long as I do, I appreciate every moment of it and I try and keep those people that I’ve lost and even the people that I don’t know that have been taken, I kind of live for them because I’m still here and they’re not. So I’m not going to sit on my butt and, “Woe is me.” I’m going to get out there and enjoy life, if not just for me, but for their spirit as well, which gives me a sense of solace you know…

To summarize, emotional coping with HIV over the long term meant drawing on personal resilience and positively managing negative feelings and attitudes. Participants also relied on spiritual/religious beliefs and resources to cope emotionally with their illness.

Social Supports

Participants used inner strengths to cope with their long-term HIV, but many also described a high level of social support they received from a variety of sources. Not surprisingly, female family members—often a mother or a sister--may have first become knowledgeable and involved during a participant’s early acute illness episode. Partners, other family—including older children—and friends, were noted as providing support, even though some of these individuals did not immediately accept the participant’s illness.

In addition to family and friends, encounters with caring clinicians, physicians, nurses, social workers, and clinic staff were often a first step in getting participants to accept their disease and to deal with the stigma of HIV:

My first doctor was Dr. (X) and I think God sent (this physician) because they were all compassionate. In the beginning it was all compassion. It wasn’t like “Ugh,” you know. They embraced you, and that never sent me into a depression. Never. It never got to the point where, “Oh god, my life is through now.” I never went through that portion. Later on certain things, but at that particular, at the initial point, the respect and help they gave me said, “Okay, we’re not going to focus on death. We’re going to focus on survival …”

Some participants saw the compassion of clinicians as making the difference between moving past anger or harboring fantasies of revenge. The feeling of being cared for by health care professionals was expressed by the participant who stated, “I do know that I have more health care than most of (my) friends and so I’m monitored very well and I feel that that’s a great, gives me a sense of security.” In addition to knowledgeable and caring health care professionals, institutional and community support groups provided important help.

Several participants noted the positive influence of pets in their lives. Pets offered unconditional love, but they also enabled participants to shift the focus from themselves and their illness. As one participant said, “I have pets, so it sort of made me feel needed like and responsible for something and someone.” Another person explained:

You know you’ve got to get up to let the dog out. The cat can use the litter box in the basement. So then the dog is more for motivation. The cat’s more for comfort. So the animals, I think you know the situation may be you know a lot of times people that are sick, you know if you don’t have family, an animal I think, you know if you’re an animal lover, animals I think can be good…

Overall, participants derived coping assistance from a variety of social interactions, both human and non-human. Partners, families and friends were important sources of support, while health care professionals often were instrumental in helping individuals confront their illness and begin to deal with it.

Discussion

This exploratory study elicited positive traits and resources useful in meeting the challenges of living with HIV, as perceived by long-term survivors. As noted in the literature, problems of HIV in older adults can be compounded by stigma related to HIV and its association with marginalized lifestyles, and with discrimination related to aging (Lyons, Pitts, Grierson, Thorpe, & Power, 2010). Rather than focusing on a single trait or related combination of traits, we attempted to obtain a comprehensive view of the ways in which participants coped with long-term survival of HIV.

Some of our findings were consistent with those of previous studies. Similar to a British study of HIV-infected African women, our participants engaged in self-management behavior changes and positive framing to adjust to life with HIV (Dibb & Kamalesh, 2012). Our study participants also were selective with disclosure or non-disclosure of their HIV status, a finding noted elsewhere (Emlet, 2008). In addition, several of our themes were similar to those identified by others using frameworks of resiliency (Emlet et al., 2011) and women’s social roles (Webel & Higgins, 2012).

Participants’ reliance on religion and/or spirituality as a resource was prominent in our study, a finding consistent with studies associating religion/spirituality with factors such as higher quality of life and coping ability (Tuck et al., 2001; Vance, Brennan, et al., 2011). While religion and spirituality were important, participation in organized religion was not mandatory for participants. Individuals also found spiritual comfort elsewhere, as in memories of deceased friends and relatives.

Results also confirmed the positive value of social support. Others (Chesney et al., 2003; Mavandadi, Zanjani, Ten Have, & Oslin, 2009) have reported an association of social support with decreased distress and fewer symptoms of depression among older males with HIV. Heckman and colleagues (2000) noted that African American men had higher levels of social support from family and better coping than White men, but our small, qualitative study did not distinguish race-associated differences. Lyons and colleagues (2010), in contrast to our study, observed that their Australian study participants had low support from health care workers other than their primary physicians.

Our study underscored the key role health care providers appear to have in promoting the physical and psychosocial well-being of PLWH. Participants often described a feeling of being cared for and their providers as compassionate and accepting of them in spite of their stigmatized disease and/or marginalized lifestyle. The precise role compassionate health care might have in changing the trajectory of HIV disease is unknown, but some studies have related missed clinic visits in the first year post-HIV diagnosis with increased mortality (Mugavero et al. 2009) and patient-centered care by providers with increased effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy (Beach, Keruly, & Moore, 2006). Further research is needed on the impact of patient-professional relationships on HIV disease processes.

Study limitations included sample size, recruitment from a single site, and use of a convenience sample, all of which prevent generalizability. However, even with our small sample size, we reached theme saturation to capture a significant portion of the study topics. A strength of our study was its broad overview of factors, both individual and social, that older adults have used to manage living with HIV. The narratives of these long-term survivors suggested that they had adapted to the illness over time. Although we presented discreet themes, we recognized that, in reality, these themes are not separable from each other or from the wider social context. Participants identified multiple, often interrelated positive factors they attributed to their well-being, for example, faith, family, and active engagement in treatment and in a healthy lifestyle were all identified by one participant as influential in coping with long-term survival of HIV.

Clinical Considerations

Our study has implications for HIV nursing care and research. First, given the frequent identification of the importance and power of the relationship with health care providers, it might be worthwhile to identify specific behaviors and attitudes of experienced clinicians that patients interpret as conveying the caring and compassion that is so helpful to them. This would enable modeling in clinical practice, as well as developing specific education intervention programs to teach and support health care professional education and socialization.

Second, clinics could capitalize on the practical knowledge, wisdom, and desire to give back expressed by older, long-term HIV survivors by engaging them as volunteer navigators to help newly diagnosed individuals navigate the complexities of health care for PLWH. The concept of health care system navigation, which coordinates multidisciplinary services to address patient needs, is relatively new in HIV care, but it has been shown to decrease barriers to care and improve outcomes such as enhanced physical and mental status and health-related quality of life (Bradford, Coleman, & Cunningham, 2007). Navigators could be drawn from groups of long-term survivors who are willing to share their experiences and knowledge of the system and their experiences of how they coped effectively with challenges of living with HIV. While various peer-based programs for sharing knowledge between PLWH exist, they generally have not focused on coordination of care among clinical specialties within the system, nor on outcomes such as improving access to and coordination of HIV care and adherence to treatment. Thus, developing peer navigation programs and testing the effectiveness of such programs are needed.

Third, nurses can integrate topics found in our study into HIV patient education: (a) skills related to self-management of health care, particularly problem-solving, positive re-framing, and (b) identification of resources for spiritual and social support for patients who have not yet acquired such skills. Nurses can also add to the evidence base of nursing practice by developing program- or clinic-based interventions to enhance these positive traits in patients, and to evaluate programs for effectiveness and sustainability.

Our study has identified a variety of positive traits and resources that long-term survivors of HIV have used to meet the challenges of living with HIV. We have characterized the use of these traits and resources as coping with the medical management of the disease itself; coping with the practical, everyday tasks of living day-to-day with HIV; coping with the emotional aspects of this chronic, stigmatized condition; and use of social resources within families and communities. Our findings add to the recent but growing literature on long-term survivorship with HIV, and to the increasing recognition of the value of positive psychological traits and resources for coping with chronic illness. Individuals who have long-term experiences in coping with the challenges of living with HIV can provide new insights for clinicians to better assist patients who have been recently diagnosed or who have had difficulties managing everyday life with HIV. The study of positive traits and resources from the patient’s perspective provides a basis for enhancing patient-centered clinical practice and research, thereby offering additional avenues for addressing the health care needs of HIV populations.

Clinical Considerations.

Nurses and other clinicians should consider renewed attention to the value of the patient-provider relationship as a foundation in therapeutic patient care.

Nurses and other clinicians can leverage the wisdom of patients who have learned to cope in diverse ways with the multiple challenges of living with HIV. By doing so they may gain insight into ways of improving care and link these individuals with patients who are struggling to cope.

Integrating novel concepts such as positive strengths and traits into clinical practice may include developing programmatic elements and interventions to enhance evidence-based nursing practice and further the development of nursing science related to HIV.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Grant #NR011907 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), Barbara Daly, PhD, RN, FAAN, Principal Investigator. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NINR or the National Institutes of Health. We wish to thank the staff at the clinic site where this study was conducted for their invaluable help in facilitating this study. We are grateful to our participants for their willingness to share their stories with us.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article (including relationships with pharmaceutical companies, biomedical device manufacturers, grantors, or other entities whose products or services are related to topics covered in this manuscript) that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jacquelyn Slomka, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH, USA.

Jung-won Lim, Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH, USA.

Barbara Gripshover, School of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University University Hospitals Case Medical Center Cleveland, OH, USA.

Barbara Daly, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH, USA.

References

- Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? British Medical Journal. 2001;322(7294):1115–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(6):661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W. HIV system navigation: An emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(1):S49–S58. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9987. doi:10.1089/apc.2007.9987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Persons aged 50 and over. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/over50/index.htm.

- Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Johnson LM. Social support, distress, and well-being in older men living with HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;33(Suppl. 2):S185–S193. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibb B, Kamalesh T. Exploring positive adjustment in HIV positive African women living in the UK. AIDS Care. 2012;24(1-2):143–148. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.597710. doi:10.1080/09540121.2011.597710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA. Truth and consequences: A qualitative exploration of HIV disclosure in older adults. AIDS Care. 2008;20(6):710–717. doi: 10.1080/09540120701694014. doi:10.1080/09540120701694014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA, Tozay S, Raveis VH. “I’m not going to die from the AIDS”: Resilience in aging with HIV disease. Gerontologist. 2011;51(1):101–111. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq060. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson BL, Joiner T. Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science. 2002;13(2):172–175. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00431. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R, Liu L, Catalan J, Sherr L. What is the evidence for effectiveness of interventions to enhance coping among people living with HIV disease? A systematic review. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16(5):564–587. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.580352. doi:10.1080/13548506.2011.580352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman TG, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ, Kalichman SC, Masten J, Goodkin K. Late middle-aged and older men living with HIV/AIDS: Race differences in coping, social support, and psychological distress. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92(9):436–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Hayward H. Do positive psychosocial factors predict disease progression in HIV-1? A review of the evidence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(5):546–554. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177216c. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177216c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, Laurenceau JP, Balbin E, Klimas N, Solomon G. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(6):1013–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Ironson D, Balbin E, Kremer H, George A, Fletcher MA. View of God as benevolent and forgiving or punishing and judgmental predicts HIV disease progression. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;34(6):414–425. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9314-z. doi:10.1007/s10865-011-9314-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Petitto JM, Gu H, Gaynes BN, Barroso J, Golden RN, Evans DL. Progression to AIDS, a clinical AIDS condition and mortality: Psychosocial and physiological predictors. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(6):1059–1073. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005949. doi:0.1017/S0033291702005949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, Pitts M, Grierson J, Thorpe R, Power J. Aging with HIV: Health and psychosocial well-being of older gay men. AIDS Care. 2010;22(10):1236–1244. doi: 10.1080/09540121003668086. doi:10.1080/09540121003668086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavandadi S, Zanjani F, Ten Have TR, Oslin DW. Psychological well-being among individuals aging with HIV: The value of social relationships. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51(1):91–98. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318199069b. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e318199069b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Lin H, Willig JH, Westfall AO, Ulett KB, Routman JS, Allison JJ. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(2):248–256. doi: 10.1086/595705. doi:10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda S, Raboud J, Mustard C, Bavoumi A, Lavis JN, Rourke SB. Employment status is associated with both physical and mental health quality of life in people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2011;23(4):435–443. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507952. doi:10.1080/09540121.2010.507952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. The American Psychologist. 2005;60(5):410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(5):467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593. doi:10.1002/jclp.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuck I, McCain NL, Elswick RK., Jr. Spirituality and psychosocial factors in persons living with HIV. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;33(6):776–783. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01711.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE. Aging with HIV: Clinical considerations for an aging population. The American Journal of Nursing. 2010;110(3):42–47. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368952.80634.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, Brennan M, Enah C, Smith GL, Kaur J. Religion, spirituality, and older adults with HIV: Critical personal and social resources for an aging epidemic. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2011;6:101–109. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S16349. doi:10.2147/CIA.S16349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, Mugavero M, Willig J, Raper JL, Saag MS. Aging with HIV: A cross-sectional study of comorbidity prevalence and clinical characteristics across decades of life. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2011;22(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.04.002. doi:10.2147/CIA.S16349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel AR, Higgins PA. The relationship between social roles and self-management behavior in women living with HIV/AIDS. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22(1):e27–e33. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutoh AK, English GN, Daniel M, Kendall KA, Cobran EK, Tasker VC, Mbulaiteye A. Pilot study to assess HIV knowledge, spirituality, and risk behaviors among older African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011;103(3):265–368. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]