Abstract

A case of a perforated black esophagus treated with minimal invasive surgery is presented. A 68-year-old women underwent a right-sided hemihepatectomy and radio frequency ablation of two metastasis in the left liver lobe. Previous history revealed a hemicolectomy for an obstructive colon carcinoma with post-operative chemotherapy. Postoperatively she developed severe dyspnea due to a perforation of the esophagus with leakage to the pleural space. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) to adequately drain the perforation was performed. Gastroscopy revealed a perforated black esophagus. The black esophagus, acute esophageal necrosis or Gurvits syndrome is a rare entity with an unknown aetiology which is likely to be multifactorial. The estimated mortality rate is high. To our knowledge, this is the first case published of early VATS used in a case of perforated black esophagus.

Keywords: Black esophagus, Acute esophageal necrosis, Video assisted thoracoscopic surgery, Gastrointestinal surgery, Perforated esophagus

Core tip: We describe a clinical case with a review of relevant literature of the rare syndrome black esophagus, also known as acute esophageal necrosis or Gurvits syndrome. It concerns a case of a perforated black esophagus treated with video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). To our knowledge, this is the first case published of early VATS used in a case of perforated black esophagus.

INTRODUCTION

The black esophagus, also known as acute esophageal necrosis or Gurvits syndrome, is a rare clinical syndrome with an unknown pathophysiology, though likely to be multifactorial[1]. There are numerous risk factors[2]. Coffee-ground emesis, hematemesis and melena can be presenting symptoms of black esophagus[2,3]. Though the diagnosis is confirmed with gastroscopy where the esophagus is circumferentially black, differential diagnosis consists of malignant melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, pseudomelanosis, melanosis, pseudomembranous esophagitis, infections and ingestion of corrosives[2,4-10]. Mortality and morbidity of the black esophagus is high and therapy includes adequate treatment of underlying illness, systemic fluid resuscitation, intravenous proton pump inhibitors or histamine receptor blocker, total parenteral nutrition and nil-per-os[2]. Surgery is reserved for patients with a perforated esophagus resulting in mediastinitis or abscess formation[1]. We present a case of a black perforated esophagus treated with early video assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

CASE REPORT

A 68 year-old woman was treated 6 mo prior to the current admission for adenocarcinoma of the descending colon. During this admission the patient underwent a left-sided hemicolectomy in an acute setting due to an obstructive ileus. In the post-operative setting the patient received adjuvant chemotherapy (two cycles of capox/bevacuzimab and one cycle of capox) because of liver metastasis. Despite chemotherapy the size, but not the number, of liver metastasis progressed in segments two, three, seven and eight.

It was decided to perform a right hemihepatectomy, and radio frequency ablation of two metastasis in the left liver lobe. In the same setting a cholecystectomy was performed. A nasogastric tube was inserted non-traumatically for post-operative feeding.

On the fourth postoperative day the patient developed severe dyspnea, based on a left sided tension pneumothorax, for which a chest tube was inserted. She was admitted to the ICU for mechanical ventilation due to persisting dyspnea, later complicated with severe sepsis and multi-organ failure, treated with fluid resuscitation, vasopressive medication and haemodialysis.

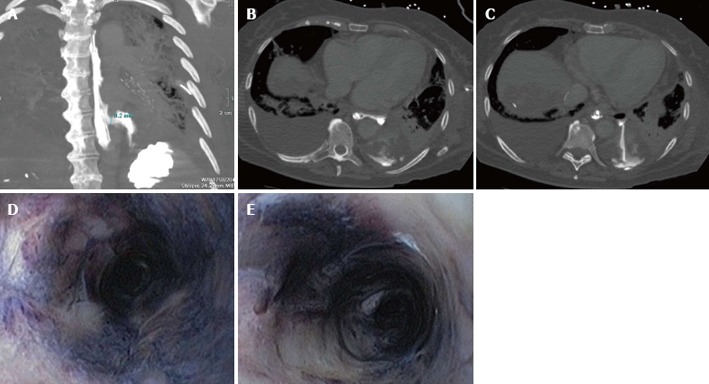

Subsequent computed tomography (CT-scan) of the chest revealed a pneumomediastinum and leakage of contrast given via the nasogastric feeding tube in the pleural space (Figure 1A-C), with adequate positioning of the nasogastric-tube.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography-thorax scan with contrast given via the nasogastric feeding tube. A: A coronal coupe where the esophagus is seen to the left of the vertebral column and the perforation lights up two thirds of the esophagus with leakage of contrast into the pleural space; B and C: Transversal coupes of the thorax with contrast leakage via the esophagus into the pleural space; D and E: A circumferentially black-appearing esophagus at endoscopy.

Laboratory investigation of the pleural fluid showed elevated amylase levels (3312 U/L). Suspicion of an esophageal perforation was high, given the elevated pleural-amylase and the result of the CT-scan. This was confirmed with gastroscopy. At 32 cm from the teeth, a perforation was seen. Moreover, the gastroscopy revealed a circumferentially black-appearing esophagus (Figure 1D and E), with an abrupt stop of the abnormal-appearing mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction.

Stenting was considered, but because the friable mucosa and the proven perforation a right-sided video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) procedure (video assisted thoracoscopy) was performed, in order to adequately drain the pneumomediastinum, placing an intrathoracic flushing-system-drain near the perforation. Of note, perioperatively the esophagus appeared normal from the outside, suggesting that there was no transmural necrosis of the esophagus.

The patient was treated postoperatively with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Serological tests of immunodeficiency-, herpes- and cytomegalovirus were negative.

Twenty three days after initial diagnosis, the esophageal mucosa appeared normal on a repeat gastroscopy and the perforation had healed. The patient was discharged from the ICU in good condition. In the further post-operative course to date , two years post surgey, the patient needs monthly gastroscopy for esophageal dilatation because of strictures.

DISCUSSION

The black esophagus, also known as acute esophageal necrosis or Gurvits syndrome is a rare clinical entity. The exact pathology of the black esophagus is unknown, although it is likely to be multifactorial[1]. The prevalence of black esophagus is estimated between 0.01% and 0.2%[11-13].

There are several etiological theories[1]. One of them is ischemic damage due to hemodynamic compromise and a low-flow state, as can be seen in septic patients. Mucosal damage due to gastric acids, as seen in gastric outlet obstruction, may be a risk factor for black esophagus. Another possible explanation is esophago-gastroparesis and mucosal barrier failure in malnourished and debilitated patients[1].

In the case described above, there could have been more than one cause of the esophageal perforation. The patient was known to have metastatic colon cancer and to be in a sepsis, causing a low-flow state. It is likely, given the clinical course, that the esophageal perforation was caused by ischemia of the esophagus. Histological findings in the literature describe full-thickness necrosis, though mostly necrosis of the mucosa, and submucosa even extending to the muscularis propria is seen, as discussed later[1].

Known risk factors for developing a black esophagus are greater age (average 67 years), male sex (male:female = 4:1), cardiovascular disease, hemodynamic compromise, hypoxemia, hypercoagulable state, gastric outlet obstruction, malnutrition, malignancies, diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency and trauma[2].

Symptoms of a black esophagus are often upper gastrointestinal bleeding conditions such as coffee-ground emesis, hematemesis and/or melena[2,3]. The distal third of the esophagus is most frequently affected, although it can affect the entire esophagus[2]. The esophagus demonstrates the characteristic diffuse, circumferential black discoloration at endoscopy, with underlying friable hemorrhagic tissue, and a sharp transition to normal-appearing mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction[2]. Biopsy, though recommended, is not required. Histological findings of the black esophagus include necrosis of the mucosa, submucosa even extending to the muscularis propria, absence of viable epithelium and widespread necrotic debris. Common associated findings are leucocytic infiltrates, severe inflammatory changes, deranged muscle fibres and visible vascular thrombi[1]. In the differential diagnosis of black esophagus, factors including malignant melanoma, acanthosis nigricans, pseudomelanosis, melanosis, pseudomembranous esophagitis, infections (candida albicans, herpes simplex viruses-1, cytomegalorvirus and Lactobacillus acidophilus) and ingestion of corrosives should be considered[4-10].

Common complications are development of strictures or stenosis of the esophagus, mediastinitis or mediastinal abcesses, perforation or death, with an estimated mortality rate of 32%[2]. Therapy, though not standardized or evidence based, consists of treating the underlying illness, systemic fluid resuscitation, intravenous proton pump inhibitors or histamine receptor blocker, total parenteral nutrition and nil-per-os. Antibiotic therapy is controversial[1]. The use of a nasogastric tube should be resisted , if possible. Surgery is reserved for patients with a perforated esophagus resulting in mediastinitis or abscess formation[1].

To our knowledge, this is the first case published with early use of VATS in the case of a perforated black esophagus.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers dos Santos JS, Gurvits GE S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

References

- 1.Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3219–3225. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i26.3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1974-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rejchrt S, Douda T, Kopácová M, Siroký M, Repák R, Nozicka J, Spacek J, Bures J. Acute esophageal necrosis (black esophagus): endoscopic and histopathologic appearance. Endoscopy. 2004;36:1133. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller A, Aguilar H, Burgart L, Gostout CJ. The black esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2210–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90844-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raven RW, Dawson I. Malignant melanoma of the oesophagus. Br J Surg. 1964;51:551–555. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800510723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimball MW. Pseudomelanosis of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1978;24:121–122. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(78)73478-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma SS, Venkateswaran S, Chacko A, Mathan M. Melanosis of the esophagus. An endoscopic, histochemical, and ultrastructural study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumas O, Barthélémy C, Billard F, Dumollard JM, Boucheron S, Calmard P, Rousset H, Audigier JC. Isolated melanosis of the esophagus: systematic endoscopic diagnosis. Endoscopy. 1990;22:94–95. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ertekin C, Alimoglu O, Akyildiz H, Guloglu R, Taviloglu K. The results of caustic ingestions. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1397–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacy BE, Toor A, Bensen SP, Rothstein RI, Maheshwari Y. Acute esophageal necrosis: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:527–532. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katsinelos P, Pilpilidis I, Dimiropoulos S, Paroutoglou G, Kamperis E, Tsolkas P, Kapelidis P, Limenopoulos B, Papagiannis A, Pitarokilis M, et al. Black esophagus induced by severe vomiting in a healthy young man. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:521. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-4248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben Soussan E, Savoye G, Hochain P, Hervé S, Antonietti M, Lemoine F, Ducrotté P. Acute esophageal necrosis: a 1-year prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:213–217. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]