Abstract

Objective

To explore perceptions of primary care physicians’ (PCPs) and oncologists’ roles, responsibilities, and patterns of communication related to shared cancer care in three integrated health systems that used electronic health records (EHRs).

Study design

Qualitative study.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with ten early stage colorectal cancer patients and fourteen oncologists and PCPs. Sample sizes were determined by thematic saturation. Dominant themes and codes were identified and subsequently applied to all transcripts.

Results

Physicians reported that EHRs improved communication within integrated systems, but communication with physicians outside their system was still difficult. PCPs expressed uncertainty about their role during cancer care, even though medical oncologists emphasized the importance of co-morbidity control during cancer treatment. Both patients and physicians described additional roles for PCPs, including psychological distress support and behavior modification.

Conclusions

Integrated systems that use EHRs likely facilitate shared cancer care through improved PCP-oncologist communication. However, strategies to facilitate a more active role for PCPs in managing co-morbidities, psychological distress and behavior modification, as well as to overcome communication challenges between physicians not practicing within the same integrated system, are still needed to improve shared cancer care.

Introduction

The incidence of cancer is increasing in patients over the age of 50 years,1 who often have multiple chronic conditions.2,3 Because cancer patients with co-morbidities experience worse disease free and overall survival,4–9 this presents challenges for effective cancer care. Better integration of primary care providers (PCPs) into the cancer care team may be an important strategy to alleviate the burden of co-morbidities during cancer care.

Shared cancer care, where clinicians from different specialties jointly manage a patient, includes the cancer survivorship continuum from diagnosis to post-treatment surveillance.10 One shared cancer care model proposes that PCPs manage chronic diseases, referrals, and physical and emotional health, while oncologists manage cancer treatment and communicate with PCPs about survivorship care.10 Responsibilities are proportionally divided between PCPs and oncologists depending on the cancer survivorship phase. Another model describes fluctuating oncologist and PCP participation, depending on whether a patient has active, remission, or relapsed cancer.11 Both models interpret shared care as alternation of primary responsibility between oncologists and PCPs based on the survivorship phase, the success of which depends on the quality of hand-offs between clinicians. However, PCPs are often disconnected from the cancer team due to ineffective communication and poor integration of treatment plans between physicians.12,13 Despite the importance of the PCP’s role, effective integration and communication between clinicians is not well understood.

In this study, we interviewed cancer patients with additional co-morbidities, PCPs, and oncologists to describe clinicians’ roles and patterns of communication in shared cancer care. We examined these issues within three integrated health systems that co-locate PCPs with oncologists and utilize electronic health records (EHRs) that can facilitate communication and potentially enhance the process of care coordination.14,15

Methods

Between April through August 2009, we approached 26 patients receiving primary care and colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment at a VA health system and 23 PCPs and oncologists [including radiation oncology (RO), surgical oncology (SO), and medical oncology (MO)] practicing in either one of three settings: VA, a local comprehensive cancer center, or a county health system. Clinical sites were integrated health systems located within the same geographic area and used an EHR. Ten patients and 14 physicians were enrolled for in-depth individual interviews.16

Patients with non-metastatic CRC diagnosed within two years prior to enrollment were recruited from a local VA cancer registry. We first reviewed medical records to identify patients who received primary care at the same VA health system for a co-morbid medical illness (i.e., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes mellitus) known to impact CRC outcomes.4 Early stage CRC patients were then chosen for interviews due to their favorable prognosis.17 To address perceptions that VA practice patterns are distinctly different, we purposively sampled PCPs and oncologists from VA and non-VA settings to assess if responses were thematically different.18 Patient subjects were recruited until thematic saturation was achieved, defined a priori as when the final three patient interviews yielded no new information. Thematic saturation for clinician interviews occurred when ongoing data analysis yielded no new information or redundancy of theme categories across all sites and specialties.16

Three in-depth, semi-structured interview guides18 were developed for patients, oncologists, and PCPs to assess their perceptions of communication and care coordination for cancer patients with co-morbidities. Patient interviews asked about cancer’s impact on their life, treatment goal communication with physicians, and co-morbidity related symptoms. PCPs were asked to envision cases of cancer patients with co-morbidities, and then describe their roles and communication with patients and oncologists regarding co-morbidity management and overall medical care. Oncologists described treatment planning for complex cancer patients, their perception of PCP roles in cancer care, and communication with patients and PCPs. Structured interview probes asked participants about the impact of EHRs on delivery of integrated care and communication. Informed consent was obtained before each interview. Interviews were conducted in person for approximately 20–45 minutes, audio tape recorded, and professionally transcribed. Patient subjects received a $15 cafeteria voucher. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

The research team included an expert in doctor-patient communication and qualitative research, a primary care provider with expertise in chronic disease epidemiology, an oncologist, and a project coordinator with qualitative research experience. At least two investigators identified emerging themes and coded meaningful sections of each transcript. All investigators reviewed transcripts independently to improve reliability. The group discussed dominant themes and codes until consensus was reached. The final codes were applied to all transcripts.16

Results

Eight (58%) of 14 physicians were oncology specialists. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and physician characteristics are summarized in Table 2, stratified by primary care and oncology categories. Qualitative analysis identified 3 dominant themes pertaining to shared cancer care: 1) communication among physicians was partially facilitated by the EHR, 2) lack of clarity persisted regarding the prioritization and responsibility for co-morbidity management, and 3) participants described two additional shared cancer care roles for PCPs.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of colon cancer patients interviewed (N=10)

| Patient Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 40 – 60 years | 3 (30) |

| 60 – 80 years | 5 (50) |

| >80 years | 2 (20) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 (100) |

| Female | 0 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 6 (60) |

| Black/African American | 3 (30) |

| Hispanic | 1 (10) |

| Time since cancer treatment began | |

| 3–6 months | 2 (20) |

| 6–12 months | 5 (50) |

| 12–24 months | 3 (30) |

| Education completed | |

| Primary or secondary school | 4 (40) |

| Some college/trade school | 6 (60) |

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of physicians interviewed (N=14)

| Physician Characteristics | Primary Care (N=6) n (%) |

Oncology (N=8) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 4 (67) | 2 (25) |

| Male | 2 (33) | 6 (75) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 2 (33) | 5 (63) |

| Black/African American | 1 (17) | 0 (0) |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 2 (25) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 (50) | 1 (12) |

| Practice setting | ||

| VA hospital | 1 (17) | 6 (75) |

| Comprehensive cancer center | 2 (33) | 2 (25) |

| County health system | 3 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Oncology specialty | ||

| Medical oncology | 3 (37.5) | |

| Surgery oncology | 3 (37.5) | |

| Radiation oncology | 2 (25) |

Electronic health record connects physicians in integrated health systems

Physicians believed that the EHR improved communication and efficiency within their hospital system.

“Here everything is electronic…I think that’s the way to communicate…we e-mail sometimes” (MO 4)

“Sometimes I’ll put [a question] in my progress note and identify [PCP] as a co-signer so they can see my thinking and address any [chronic disease] issue…” (MO 5)

“I don’t have to contact [oncologists] too much about basic things … [electronic notes] are all accessible.” (PCP 11)

“We are totally on EMR … we [can] reference results and then e-mail somebody [through the EMR].” (PCP 13)

The perceived value of the EHR in an integrated health care system was also reflected in physicians’ reported difficulty communicating with physicians from outside hospitals.

“Communication can definitely become a barrier, especially people not inside your same system…trying to figure out what the other one’s doing” (MO 6)

“The [electronic] note… is easily accessible by every other physician… on the same system…it’s obviously not as easy [with external physicians]” (PCP 8)

However, when describing communication outside one’s integrated system, physicians reported problems with sending letters and believed patients were becoming the messengers.

“Some patients [say] I just talked to your surgeon about my case. Why do I have to talk to you again [about] the whole thing?” (MO 4)

“Sometimes the patients convey messages… between specialists, but can develop conflict if the patient has a different agenda.” (PCP 11)

“[with the EHR] the flow of information is pretty good … [getting outside records] can be hugely inefficient.” (RO 17)

Despite the EHR and other advantages of an integrated system, physicians within the same system still used direct communication via phone calls or email to communicate when specific urgent problems arise.

“I don’t have to contact [oncologists] too much about basic things…[EHR notes are] all accessible…when I’m contacting them…usually email, occasionally paging…if urgent… to clarify something that isn’t in the note or a major discrepancy between the patient and the oncologist” (PCP 11)

“We have a once-a-week tumor board… to get good communication with [other physicians]” (RO 15)

There were no substantive responses from participants describing the use of EHRs to develop shared cancer care models despite specific probes about the use of EHRs and care coordination.

Co-morbidity management role: prioritization and responsibility

All participants acknowledged the primacy of cancer treatment compared with co-morbidities. Patients, oncologists, and PCPs reported some uncertainty about the role of PCPs and priority of co-morbidity management during acute cancer treatment.

“The cancer has really been the forefront …but when I feel better… the breathing problem [will be] back to the front.” (patient 6)

“Other illnesses take an immediate back seat [to cancer]…” (SO 3)

To further emphasize this point, several PCPs perceived themselves in marginal roles.

“[Patients’] most important concern is getting [their cancer] treated … as their cancer gets treated… and prognosis [improves] then you might go back to treating more intensively the chronic illness” (PCP 9)

“[Cancer] diminishes the role of primary care…it interrupts [a patient’s] regular routine …” (PCP 11)

Medical oncologists, in contrast, described how adverse effects of cancer treatment can affect co-morbidity control and that uncontrolled co-morbidities limit cancer treatment options.

“If they have long term survival then their co-morbid illnesses have to be managed much more carefully… If the patient has very severe co morbid illnesses, sometimes you’re not able to treat the cancer as aggressively” (MO 5)

In fact, oncologists advocated active PCP involvement during acute cancer care.

“Some of our treatment…may aggravate [co-morbidities], so we need closer collaboration with primary care” (MO 4)

In addition, two PCPs discussed needing to assume more assertive roles in treating the chronic illnesses of cancer patients.

“I really took a back seat…had to actively initiate contact with the oncologist” (PCP 13)

“Didn’t want to lose focus on hypertension… make sure that cancer doesn’t end up being a distracter” (PCP 11)

The theme of role uncertainty was crystallized by conflicting views of medical oncologists about who provides primary care during cancer treatment. One view was that oncologists orchestrate all aspects of care during cancer management but utilize PCPs as a co-morbidity consultant.

“It’s the difference between principal care and primary care…not their primary care, but who will…have a grasp of the whole picture of cancer treatment…” (MO 4)

“I encourage patients to continue the management of [chronic illness] with their PCP…I’m so sub-specialized now that I don’t really feel comfortable managing.” (MO 6)

The other medical oncology view wanted to let the oncologist assume responsibility for both cancer and co-morbidities to facilitate patient convenience.

“…in most cases, I take on a primary care role…because they’re coming in very frequently for oncology care…and [patients] don’t feel well enough to go to multiple physicians, so I…take care of any problem that might arise” (MO 5)

Surgical and radiation oncologists were clear in only managing cancer related issues.

“We don’t control the diabetes…We focus only on the cancer.” (RO 15)

Additional PCP roles: psychological distress and behavior modification support

Patient, oncologists, and PCPs identified two additional roles for PCPs during active cancer care. The first PCP role involved support for psychological distress from cancer diagnosis and treatment.

“I find that patients… often use their primary care appointments during their cancer treatment almost as adjunct therapy sessions… I have patients with very early stage disease that… are cured, but still have trouble refocusing on their chronic conditions because they’re so traumatized” (PCP 11)

“My PCP is good about listening to my concerns and problems…The cancer clinic needs to listen closer” (patient 6)

Oncologists noted that their role in psychological support involves promoting hope, rather than exploring psychological distress.

“I try to always give some kind of optimistic perception…hope but with that specific patient’s reality.” (SO 1)

In addition to the psychological impact of cancer, physicians also described the cancer experience as an impetus for patients to consider healthy behavior changes.

“Patients… say ok, I’m not going to go through [cancer treatment]…just to get lung cancer because I’m still smoking, so… [they] make themselves quit.” (MO 10)

“The vigilance regarding the cancer gets translated to vigilance about other diseases.” (PCP 11)

While patients often improve their weight or smoking habits due to cancer and treatment, maintenance in the cancer surveillance phase is difficult.

“Patients get cancer and they lose weight… their [co-morbidities] become in excellent control…I try to encourage the patient’s… not to gain back… [but] sometimes they gain it back.” (MO 5)

Thus, the second PCP role that emerged was support for maintenance of healthy behavior modification and goal setting.

“The treatment goal is… to understand there’s a [diabetes] target to reach, and we are going to just work with each other to reach that target. Some [patients] have trouble understanding…, but…I explain this is the target and they have to reach it.” (PCP 7)

Despite being ready for behavioral change, patients often do not get the behavior modification support they need during cancer treatment. The need for increased PCP involvement was best articulated by a patient who described minimal support from oncologists for behavioral modification.

“[Cancer doctors] didn’t really get deep into [health goals]. It was just to let me be aware…They gave me books and stuff.” (Patient 10)

Discussion

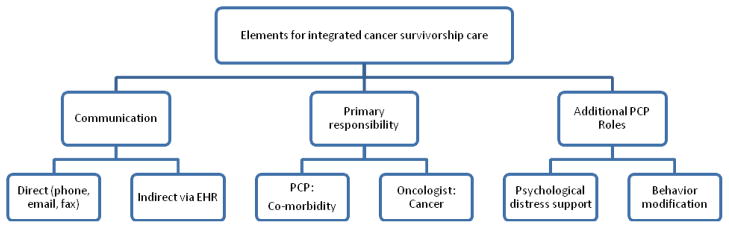

Our study revealed insights into three major themes regarding clinicians’ roles and communication in shared cancer care within integrated health systems (Figure 1). First, EHRs facilitated communication within an integrated system, but communication with outside systems remained difficult. Second, PCPs were uncertain about co-morbidity prioritization during cancer care, but oncologists highlighted the importance of co-morbidity management by PCPs during cancer treatment. Lastly, participants described two additional roles for PCPs during chronic cancer care: support for psychological distress and behavior modification.

Figure 1.

Coordination of primary care physicians and oncologists within Integrated Health Systems using Electronic Health Records: modes of communication, defined responsibilities, and additional roles for PCPs in cancer care.

PCPs and oncologists in integrated systems used the EHR for management questions, communicate decisions, and review medical records, whereas external physician communication required phone calls, letters, or using patients as messengers. Although physicians within integrated systems used direct verbal or email communication for specific questions, the EHR enabled asynchronous communication for information exchange and care coordination between PCPs and oncologists.14 Participants did not cite any electronic communication strategies which could facilitate communication outside of one’s system.

One possibility to improve integration of physicians from different health systems is web portals, where patients or physicians can access medical information electronically via an encrypted website.19,20 Web portal technologies could potentially enable all PCPs to access their patient’s cancer history and communicate with the oncology team electronically. Telemedicine, such as video conferences for virtual tumor boards or treatment planning sessions,21,22 might also help overcome communication barriers to shared care.

Figure 1 highlights significant PCP roles in cancer survivorship care for co-morbidity management, psychological support and behavior modification counseling. Previous shared care models utilized primary responsibility hand-offs between PCPs and oncologists. Our data suggest that active coordination between physicians with clear delineation of roles throughout cancer care is needed to manage complex cancer patients. Integrated health systems using EHRs not only identify areas of potential improvement in this area but also highlight how shared cancer care and coordination may evolve in the future.14,23 Participants supported PCPs managing co-morbidity in cancer patients, while oncologists focused on cancer treatment. However, all participants expressed uncertainty regarding the prioritization of co-morbidity management. Patients and PCPs stated that cancer became the main management priority, while co-morbidities took backstage and were readdressed if cancer treatment was successful. Conversely, medical oncologists highlighted the importance of PCPs in acute cancer care based on co-morbidity impact on cancer treatment options, e.g., steroid induced hyperglycemia or uncontrolled hypertension from bevacizumab. Medical oncologists had mixed views regarding their role in co-morbidity management. Most felt that they coordinated cancer care, but specific co-morbidity management was a PCP role. A minority of medical oncologists managed co-morbidities and cancer for patient convenience. Surgical and radiation oncologists consistently felt that co-morbidities were the PCP role. Evidence suggests that patients, PCPs and oncologists agree on minimal involvement of oncologists with co-morbidity management.24

Another theme that emerged was PCP recognition of psychological distress and behavior modification needs (Figure 1). Many PCPs described their role as helping patients cope with distress, whereas both medical and surgical oncologists described framing discussions to maintain hope. Cancer survivors can continue to have anxiety after cancer treatment;25 no guidelines on psychosocial support management for survivors exist.26,27 Patient surveys suggest that PCPs can contribute to cancer patients’ quality of life and psychological state through coping support and mental health referrals when needed, 28,29 while oncologists can focus on balancing hope with honest disclosure.30

Cancer diagnosis and treatment completion are teachable moments for behavior modification31 where PCPs can provide tools for healthy lifestyle changes. However, given time constraints PCPs face, greater clarification and support is needed for the PCP role in behavior modification during cancer survivorship.32 Once psychosocial needs are identified, PCPs may refer to ancillary services, such as support groups, psychologists, nutritionists, etc. if they are unable to directly address these issues.33 Certain integrated health settings such as the VA have effectively implemented behavioral psychologists as part of the primary care team to assist in coping or behavior modification strategies and teach PCPs techniques that briefly integrate these strategies into routine clinic visits.33,34

Our study has several limitations. The small sample size and study design cannot provide quantitative estimates of observed patterns and themes. Qualitative research is by design hypothesis generating and develops novel conceptual models rather than tests specific causal relationships of an a priori model. Generalizability is limited by inclusion of only male veterans and physicians from one geographic area. Consistent with qualitative methodology, the study used purposive sampling to identify a broad representation of specialists involved in shared care across three different integrated health systems.

Given the effect of co-morbidities on cancer survival outcomes, PCPs skilled in chronic disease management are necessary throughout cancer survivorship. Our study suggests a more active role for PCPs in managing co-morbidities, psychological distress and behavior modification in shared cancer care. Novel strategies are needed to clarify responsibilities at the PCP-oncologist interface and enhance PCP engagement within acute cancer care. While EHRs may improve communication between PCPs and oncologists within integrated systems, innovative information technology-based interventions are needed to overcome the challenges to achieve shared care between physicians from different systems.14

Take away points.

The following themes regarding primary care for cancer patients with co-morbidities were observed:

The electronic health record facilitates communication between physicians within integrated health systems, but novel technologies are still needed to communicate with physicians from disparate medical systems and further coordination is needed for shared cancer care within integrated health systems.

All participants described three roles for primary care physicians in shared active cancer care: co-morbidity management, psychological distress support, and behavior modification.

The emphasis and mechanisms for primary care involvement are unclear among different physicians.

Acknowledgments

This article is the result of work supported by use of facilities and a locally funded pilot grant from the Houston Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence (FP90-020), Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and by a Cancer Prevention and Population Sciences pilot grant from the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine. Dr. Naik received additional support from the National Institute of Aging (K23AG027144) and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Dr. Singh received additional support from the National Cancer Institute (K23CA125585).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest to report

References

- 1.Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LAG, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Cancer. 2002;94(10):2766–2792. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koroukian SM, Murray P, Madigan E. Comorbidity, disability, and geriatric syndromes in elderly cancer patients receiving home health care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(15):2304–2310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogle KS, Swanson GM, Woods N, Azzouz F. Cancer and comorbidity: redefining chronic diseases. Cancer. 2000;88(3):653–663. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<653::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Comorbidity and age as predictors of risk for early mortality of male and female colon carcinoma patients: a population-based study. Cancer. 1998;82(11):2123–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross CP, Guo Z, McAvay GJ, et al. Multimorbidity and survival in older persons with colorectal cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(12):1898–1904. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hines RB, Shanmugam C, Waterbor JW, et al. Effect of comorbidity and body mass index on the survival of African-American and Caucasian patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(24):5798–5806. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Maas HAAM, Houterman S, et al. Comorbidity in older surgical cancer patients: influence on patient care and outcome. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(15):2179–2193. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyerhardt JA, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on outcomes in patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(3):433–440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SM, Lim MK, Shin SA, Yun YH. Impact of prediagnosis smoking, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance on survival in male cancer patients: National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):5017–5024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–5124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen HJ. A model for the shared care of elderly patients with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57 (Suppl 2):S300–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sussman J, Baldwin L. The interface of primary and oncology specialty care: from diagnosis through primary treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs. 2010;2010(40):18–24. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkind M, Towers A, Murnaghan D, Guibert R, Iverson D. Communication between family physicians and oncologists: qualitative results of an exploratory study. Cancer Prev Control. 1999;3(2):137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naik AD, Singh H. Electronic health records to coordinate decision making for complex patients: what can we learn from wiki? Med Decis Making. 2010;30(6):722–731. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10385846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh H, Naik AD, Rao R, Petersen LA. Reducing diagnostic errors through effective communication: harnessing the power of information technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):489–494. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0393-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miles MB, Huberman M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourceboo. 2. Sage Publications, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andre T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved Overall Survival With Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin As Adjuvant Treatment in Stage II or III Colon Cancer in the MOSAIC Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(19):3109–3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverman PD. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook. 1. Sage Publications Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordqvist C, Hanberger L, Timpka T, Nordfeldt S. Health professionals’ attitudes towards using a Web 2.0 portal for child and adolescent diabetes care: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(2):e12. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnipper JL, Gandhi TK, Wald JS, et al. Design and implementation of a web-based patient portal linked to an electronic health record designed to improve medication safety: the Patient Gateway medications module. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16(2):147–155. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v16i2.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinerman B, den Duyf J, Hughes A, Robertson S. Can subspecialty cancer consultations be delivered to communities using modern technology?--A pilot study. Telemed J E Health. 2005;11(5):608–615. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2005.11.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright J, Purdy B, McGonigle S. E-Clinic: an innovative approach to complex symptom management for allogeneic blood and stem cell transplant patients. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2007;17(4):187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh H, Esquivel A, Sittig DF, et al. Follow-up Actions on Electronic Referral Communicationin a Multispecialty Outpatient Setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):64–69. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1501-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2489–2495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jefford M, Karahalios E, Pollard A, et al. Survivorship issues following treatment completion--results from focus groups with Australian cancer survivors and health professionals. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(1):20–32. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobsen PB. Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of cancer survivors: current status and future prospects. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4419–4429. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanton AL. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5132–5137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathieson CM, Logan-Smith LL, Phillips J, MacPhee M, Attia EL. Caring for head and neck oncology patients. Does social support lead to better quality of life? Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:1712–1720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sisler JJ, Brown JB, Stewart M. Family physicians’ roles in cancer care. Survey of patients on a provincial cancer registry. Can Fam Physician. 2004;50:889–896. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, et al. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5636–5642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5814–5830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coups EJ, Dhingra LK, Heckman CJ, Manne SL. Receipt of provider advice for smoking cessation and use of smoking cessation treatments among cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24 (Suppl 2):S480–486. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0978-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson PJ, Strosahl KD. Behavioral health consultation and primary care: lessons learned. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2009;16(1):58–71. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9145-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner J, Zapart S, Pedersen K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of adults with cancer. Psychooncology. 2005;14(3):159–173. doi: 10.1002/pon.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]