Abstract

Objective

Test the efficacy of an intervention of safety device installation on medically-attended injury in children birth to 3 years of age.

Design

A nested, prospective, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting

Indoor environment of housing units of mothers and children.

Participants

Mothers and their children enrolled in a birth cohort examining the effects of prevalent neurotoxicants on child development, the Home Observation and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study.

Intervention

Installation of multiple, passive measures (stairgates, window locks, smoke & carbon monoxide detectors, to reduce exposure to injury hazards present in housing units.

Outcome measure

Self-reported and medically-attended and modifiable injury.

Methods

1263 (14%) prenatal patients were eligible, 413 (33%) agreed to participate and 355 were randomly assigned to the experimental (n=181) or control (n=174) groups. Injury hazards were assessed at home visits by teams of trained research assistants using a validated survey. Safety devices were installed in intervention homes. Intention-to-treat analyses to test efficacy were conducted on: 1) total injury rates and 2) on injuries deemed, a priori, modifiable by the installation of safety devices. Rates of medically attended injuries (phone calls, office or emergency visits) were calculated using generalized estimating equations.

Results

The mean age of the children at intervention was 6 months. Injury hazards were significantly reduced in the intervention but not in control group homes at one and two years (p<0.004). There was not a significant difference in the rate for all medically-attended injuries in intervention compared with control group children, 14.3 (95%CI 9.7, 21.1) vs. 20.8 (14.4, 29.9) per 100 child-years (p=0.17) respectively; but there was a significant reduction in modifiable medically attended injuries in intervention compared with control group children, 2.3 (1.0, 5.5) vs. 7.7 (4.2, 14.2) per 100 child-years, respectively (p=0.026).

Conclusions

An intervention to reduce exposure to hazards in the homes of young children led to a 70% reduction in modifiable medically-attended injury.

Introduction

Injury is the leading cause of childhood morbidity and mortality in the United States after the first year of life. Despite a 25% reduction in housing-related injuries over the past two decades, the home environment remains the leading location of injury for young children, accounting for over 13 million outpatient visits, over 4 million emergency visits, 74,000 hospitalizations, and 2,800 deaths each year in the United States.1 Risk factors that have been identified for housing-related injuries include physical hazards, poor quality housing, externalizing child behaviors in boys, low socioeconomic status, and persistent maternal depressive symptoms.2-6

Multiple controlled trials to reduce housing-related injuries have been undertaken. Most have relied on anticipatory guidance and only occasionally provided safety devices.7-10 The largest trial to date, which was conducted in the United Kingdom and randomized over 3400 families with children younger than 5 years of age, found no effect on doctor visits for injury. In fact, the intervention group had a significantly higher rate of primary care visits for injury compared with control children. The intervention received parental education about home safety, provision of free or reduced cost safety products, and installation of safety devices in 36 percent of households meeting low socio-economic criteria randomized to the intervention arm.8 None of the reported trials have undertaken comprehensive installation of safety products in the housing units for all participants. Therefore, it remains unclear whether such safety devices, if successfully installed and functioning, lead to a reduction in exposures to injury hazards and subsequent medically-attended injuries in children.

The aim of this trial was to test the efficacy of installing home safety devices such as stair gates, cabinet locks, smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, on a reduction in hazards and housing-related injuries in children. Specifically, we hypothesized that the installation of multiple, passive safety measures in the homes of children randomized to the intervention group would reduce exposure to injury hazards and medically-attended injury across unintentional residential mechanisms by 30 percent compared with children in control homes. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Methods

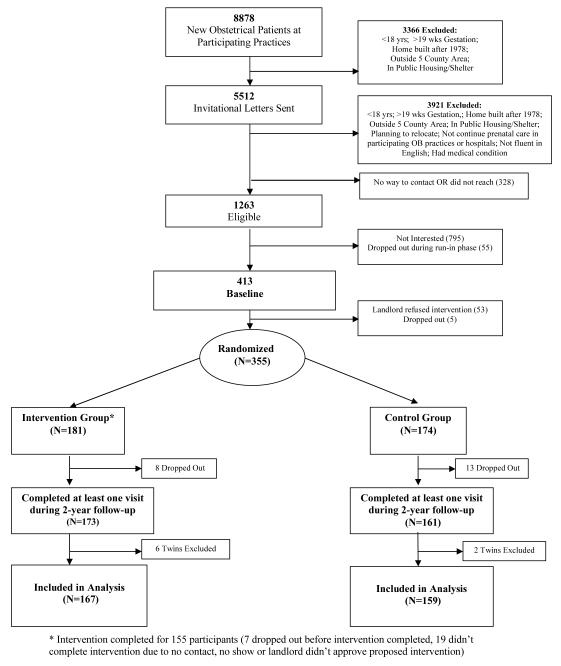

Enrollment and randomization (see Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

HOME Study Enrollment

We screened expectant mothers who attended 7 participating obstetrical practices (3 hospital-based) for eligibility in the Home Observation and Measures of the Environment (HOME) Study; a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of home injury and lead hazard control nested within a birth cohort examining the developmental effects of exposure to prevalent environmental neurotoxicants. Mothers had to be older than 18 years of age, less than 20 weeks gestation, live in a home built prior to 1978, have no plans to relocate in the next 12 months, not live in public housing or a shelter, be English speaking, and present to one of the participating prenatal clinics. Methods for enrollment and home surveys have been described previously.11 A biostatistician, who was not part of the assessment or intervention team, generated a random list of assignment codes in permuted blocks of ten stratified by urban, suburban, and rural areas surrounding the Cincinnati, Ohio regional area. The randomly generated assignments were then placed in sealed, radio-opaque envelopes. Randomization occurred after the baseline home visit (BHV) and landlord consent for rental units. Families enrolled in the study whose landlord refused the intervention were not randomized and not included in this intention-to-treat analysis (n=53, fig. 1).

Measure of Injury Hazard Exposure

Prior to randomization, all households underwent a baseline home survey of 5 predefined high-exposure and high-risk areas for injury hazards (kitchen, main activity room, stairways, child’s bedroom and bathroom) by trained research staff. The number and type of injury-related hazards for each high-risk, high-exposure area was quantified using a validated instrument.11 The instrument was developed based on an analysis of the leading mechanisms of injury resulting in an emergency visit for US children (falls, cut/pierce, struck/strike, poison, burn) using the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and a review of instruments utilized in similar studies.12-15 For the purposes of this study, we defined injury hazards to include: tap water temperature exceeding 120 degrees Fahrenheit, absent or non-functioning smoke alarms or carbon monoxide detectors, accessible and unlocked cabinets and drawers, unstable furniture or television stands, poorly maintained or un-gated and accessible stairways, unsecured area carpets or rugs, accessible stove tops and ovens, easily accessible medications, cleaners, detergents, poisons, or sharps, accessible windows (inside ledge <39 inches from floor or bed and outside ledge >4 feet above ground), uncovered electrical sockets, lack of poison control or clinic phone numbers, and unsafely stored firearms (no trigger lock or lock box for storage and/or ammunition not kept separate from firearm). The protocol and survey used to quantify injury hazards is available on request.

The area in square feet was determined for the whole house and the high-exposure/high-risk areas (stairways were not included). The density (number of hazards per 100 sq.ft.) of injury hazards was determined by dividing the number of hazards by the area of the room. The 5-area survey, which was validated for its replicability, reproducibility and representativeness of the entire living space,11 was repeated annually when the children were 12- and 24-months of age.

Interventions

Interventions were directed primarily at areas below 39 inches in height (the 75 percentile in height for a 3-year old male). Research staff, which had undergone extensive training, identified hazards at an intervention planning visit and discussed the study interventions and safety products to reduce exposure with the families. Families had the option of rejecting any interventions offered. Next, the research assistants installed all consumer product safety devices agreed upon by the families. If participants moved prior to their child turning 30mos old, their new homes were assessed for injury hazards and safety devices were installed.

Outcomes

Exposure to the indoor environment and injury outcomes was assessed by parental report through telephone interviews and annual home visit interviews. Phone interviews were conducted quarterly in the first year of the study, and bi-annually thereafter. The interview included questions initially about the child’s time of exposure to the indoor environment, followed by questions on maternal supervisory behavior and any injuries the child experienced in the prior 3 months. The interview required about 15 minutes to complete. It was not possible to mask participants to treatment status, but research interviewers who conducted the phone interviews were trained and operated separately from intervention technicians to minimize the chances of interviewers becoming unblinded to treatment status during their interactions with study participants. Participants were instructed not to reveal their group status to telephone interviewers or medical providers whether they knew or suspected it. Furthermore, the investigators, data managers and analysts were blinded to group status until all data analyses were conducted.

The primary outcome for the HOME Study was medically-attended injury events potentially modifiable by the study safety devices or equipment. Parents were given a calendar with a box of band-aids attached and asked to report injury events (of known onset) that resulted in pain, anxiety, or a visible tissue mark lasting over an hour. Medically attended injuries were defined as an injury that prompted the parents to call or visit a physician’s office, urgent care, or emergency department. It is unlikely that the installation of safety products would have effects on all home injury hazards and mechanisms. We classified injury events as modifiable, according to whether exposure to the hazard and mechanism causing the resulting injury could have been modified by one of the installed interventions (e.g., wall mounted stairgate preventing a stairway fall). Modifiable mechanisms were stairway falls, struck/strike, cut/pierce, burns, poisons, and choking mechanisms. These modifiable mechanisms were defined a priori, before enrollment of participants in the trial. Maternal reports of emergency visits for residential injury were confirmed through matching with an area-wide surveillance system (the Hamilton County Injury Surveillance System) for injury visits to emergency rooms across 12 participating hospitals in Hamilton County, Ohio.

Statistical Analysis

This analysis was by intention to treat with a priori hypotheses of a reduction in injury hazards and medically attended visits for home injuries. Data were entered into a computerized, relational database and downloaded for analysis into SAS software® (SAS Institute, version 9.1, Cary, NC). Univariate analysis of the demographic characteristics for mothers, their children, and homes was conducted. The mean number and density of hazards was compared by group assignment using t-tests with adjustment for multiple comparisons. The number and rate of ED visits, medically-attended visits and non-medically attended visits by group assignment were calculated. Numbers of all reported events, medically-attended and emergency visits, for both modifiable and total injuries were based on maternal report at the telephone survey. To account for clustering of injuries within an individual child and correlation of measurements over time, generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to model injury outcomes using a Poisson link function. The multivariable models were developed using the injury outcome as the dependent variable and the group assignment and time by group assignment as independent variables.16 To develop rate estimates the overall 3-month estimate from the generalized estimating equation model was converted to a rate per 100-child years. We estimated a sample size of 400 households to measure a 30% reduction in medically-attended injury with an alpha of 0.05 and power of 80 percent.

Results

We screened expectant mothers presenting to obstetrical practices for eligibility between February 13, 2003 and January 12, 2006. Of the 8878 women screened, 7287 (82%) were found to be ineligible due to one or more of the following reasons: less than 18 years of age, over 19 weeks of pregnancy gestation, lived in a home built after 1978 (year legislation passed banning lead-based paint) or outside the 5 Ohio county (Hamilton, Clermont, Warren, Butler, and Brown) study area encompassing the City of Cincinnati, OH, lived in public housing, shelters, group homes, or trailer homes, planned to relocate outside of the study area in the next 12 months, planned to discontinue prenatal care at participating obstetrical practices and hospitals, were not fluent in English, or had a medical condition that made them ineligible. Another 328 (3.7%) did not respond to the invitation letter and could not be contacted (figure 1).

A total of 1263 (14%) women were eligible for participation. Of these, 795 declined to participate and 55 dropped out during the run-in period for the trial prior to randomization. After the baseline home visit, but prior to randomization, an additional 53 became ineligible because the landlord refused to participate and 5 dropped out. This left 355 expectant mothers who consented to participate. These women were randomly assigned, prior to delivery of their infant, to the injury intervention (n=181) or lead intervention arm (n=174) groups. Each arm of the dual-arm, parallel group study acted as the other’s control. The first birth in the cohort was on July 16, 2003 and the final birth was on July 18, 2006.

Baseline demographic data

The demographic characteristics of mothers and their children are shown by group assignment (Table 1). The average age of the mothers at study entry was 30 years and the average age of the children at the time of the intervention planning visit was 6.3 months. The median income for the cohort was $70,000 annually; about a quarter of families in both groups made less than $30,000. There were no statistically significant differences across the demographic characteristics by group assignment in the study (p>0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Mother-Child Participants*(N=355).

| Injury (N=181) | Control (N=174) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age (mean ± s.d.) years Child Age at intervention (mean, ± s.d.) months |

29.2 ± 5.7 6.3 ± 2.7 |

30.0 ± 5.4 | ||

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Child Gender | ||||

| M | 104 | 57.5 | 85 | 48.9 |

| F | 77 | 42.5 | 89 | 51.1 |

| Child Race | ||||

| White, non-hispanic | 123 | 68.0 | 119 | 68.4 |

| Black, non-hispanic | 45 | 24.9 | 44 | 25.3 |

| Other | 13 | 7.1 | 11 | 6.3 |

| Number of Siblings | ||||

| 0 | 95 | 52.5 | 93 | 53.4 |

| 1 | 58 | 32.0 | 55 | 31.6 |

| ≥2 | 20 | 11.0 | 13 | 7.5 |

| Unknown | 8 | 4.4 | 13 | 7.5 |

| Total Household Income | ||||

| <$30,000 | 53 | 29.3 | 41 | 23.6 |

| $30,000-49,999 | 25 | 13.8 | 28 | 16.1 |

| $50,000-69,999 | 28 | 15.5 | 26 | 14.9 |

| $70,000-89,999 | 39 | 21.5 | 38 | 21.8 |

| $90,000-119,999 | 15 | 8.3 | 14 | 8.0 |

| ≥$120,000 | 18 | 9.9 | 26 | 14.9 |

| Unknown | 3 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Insurance Status | ||||

| Private | 137 | 75.7 | 137 | 78.7 |

| Medicaid/No Insurance | 44 | 24.3 | 37 | 21.3 |

| Maternal Education | ||||

| <=High school | 31 | 17.1 | 36 | 20.7 |

| < college | 52 | 28.7 | 37 | 21.3 |

| College grad / post grad | 98 | 54.1 | 101 | 58.0 |

p>0.05 across all demographic comparisons between intervention and controls

Numbers analyzed

There were 167 (92%) and 159 (91%) singleton children and their families randomized to the injury and lead interventions who completed one or more phone surveys and home visits and remained in the study through 24-months of follow-up. All of these children were included in these analyses (Figure 1). Eight sets of twins were excluded (n=6 and n=2 in intervention and control groups respectively).

Hazards Survey

At the baseline visit there was no difference in the mean number and density of hazards in the 4-room area (kitchen, main activity room, child’s bedroom and bathroom) by group assignment (Table 2). Longitudinal analysis of the number (p<0.0001) and density (p=0.014) of injury hazards in homes over the 24-month follow-up period showed a significant group by time interaction. The mean number and density of hazards in the intervention group decreased by 10 percent across the 4-rooms from baseline to the 12-month follow-up visit (p=0.001). The number and density of hazards was decreased by 15%, at the 12-month survey in the intervention compared to control homes (p<0.005). Although the mean number and density of hazards were lower in the intervention homes at 24-months, only the mean number of hazards remained statistically significantly reduced from baseline(p<0.02) and compared to controls (p=0.001). Tests were adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Table 2.

HOME Injury Study: Number and Density (number of hazards per 100 sq. ft.) of injury hazards for 5 areas¥ of home at baseline, 12, and 24-month Visits.

| Baseline Home Visit (BHV) | 12-month Visit | 24-month Visit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group (N= 167) | |||

| All Hazards | |||

| Number | 32 (7.0) | 29 (6.4)*† | 30 (5.4)**‡ |

| Density | 6.2 (1.8) | 5.6 (1.9)*† | 5.8 (2.2) |

| Control Group (N= 159) | |||

| All Hazards | |||

| Number | 32.6 (6.6) | 34 (6.1) | 33 (6.6) |

| Density | 6.1 (1.6) | 6.5 (2.6) | 6.4 (2.7) |

p<0.001 for number and density of hazards from baseline to 12-month survey

p<0.005 for number and density of hazards between control and intervention homes at 12-month visit

p<0.02 for number of hazards from baseline to 24-month survey

p<0.001 for number of hazards between intervention and control group homes

5 areas: stairways, child’s bdrm, child’s bathrm, Main Activity Room (TV & toys), kitchen

All Student t-tests adjusted for multiple comparisons.

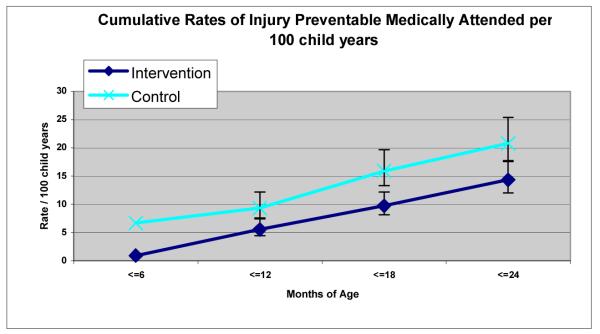

Outcomes

Modifiable Injuries

There were 134 total modifiable injury events in 92 children over the first 24-months of the study (1.4 events per child). Modifiable injuries accounted for 21 out of 74 (28%) medically-attended events in children (Table 3). The rate of modifiable, medically-attended injuries in the home was reduced by 70%, at 2.3 (95% CI 1.0, 5.5) per 100 child-years for children in intervention households versus 7.7 (95%CI 4.2, 14.2) per 100 child-years in control group children (Table 3, p=0.026).

Table 3.

Number (No.) and Rate (per 100 child-years) of Modifiable Injury by Randomized Group Assignment over 24-months of Follow-up.

| Injury Outcome | Intervention | Control | P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Rate / 100 Child-yrs (95% CI) |

No. | Rate / 100 Child-yrs (95% CI) |

||

| Modifiable Injuries | |||||

| Reported Events | 62 | 28.7 (22.0, 37.3) | 72 | 34.8 (25.8, 46.9) | 0.34 |

| Medically-attended | 5 | 2.3 (1.0, 5.5) | 16 | 7.7 (4.2, 14.2) | 0.026 |

| All Injuries | |||||

| Reported Events | 533 | 248 (203, 304) | 487 | 238 (197, 287) | 0.74 |

| Medically-attended | 31 | 14.3 (9.7, 21.1) | 43 | 20.8 (14.4, 29.9) | 0.17 |

calculation of injury rates between intervention and control groups was undertaken using generalized estimating equations with Poisson link allowing adjustment for clustering of injuries within individuals

All Injuries

Rates for all medically attended injuries among children were decreased over the 24-month follow-up by 31%, at 14.3 (95% CI 9.7, 21.1) per 100 child-years in the intervention group versus 20.8 (95%CI 14.4, 29.9) per 100 child-years in the control group (p=0.17, Table 3). There were 12 emergency visits for all home injury-related mechanisms in the intervention group compared with 10 for controls (p=0.92) and the rates of emergency visits were almost identical in control and intervention groups at 5 per 100-child years.

Adverse Events

There were two deaths to child participants enrolled in the HOME Study and reported to the Institutional Review Board at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The first death involved perinatal complications related to premature delivery and was deemed unrelated to participation in the trial. The second involved a drowning of a 1 year-old infant sibling of a child born into the study while under the supervision of the mother. The case was referred to the Cincinnati Child Protective Services Division of the police department and was deemed unrelated to the HOME Study trial by the CCHMC IRB.

Discussion

Children who lived in housing units that were randomly assigned to the intervention group had significantly fewer injury hazards and a 70% reduction in the rate of modifiable, medically-attended injury compared with children in control households. Thirty seven percent (16/43) of all medically-attended housing related injuries in the control group met our definition of ‘modifiable’. In the intervention group, we observed a 70% reduction of modifiable, medically-attended housing related injuries. Thus, if confirmed, this trial suggests that large-scale implementation of this type of intervention could result in a 30% reduction in all medically attended, housing-related injuries estimated at about 5 million medically attended visits for injury in US children less than 5 years of age each year.1, 17-19 This is the first trial of home safety we are aware of that installed and maintained safety devices in all intervention homes of children to reduce exposure to prevalent hazards across multiple mechanisms of injury.9, 10, 20, 21

A recent Cochrane Review summarized findings from prior trials of home safety, noting that “there was a lack of evidence that interventions reduced rates…(over) a range of injuries.” 22 There are two conflicting trials that have reported housing-related injury outcomes in children. The two published RCTs examined the effect of counseling, home safety checks, free equipment giveaways, or installation of home safety devices on injuries for enrolled children. The first study, a multi-center trial recruiting participants presenting to 5 Canadian pediatric emergency departments conducted by King,et.al.23 enrolled children <8 years with specific injuries, including home-related hazards (i.e. tap water scalds) in addition to bicycle crashes and other injuries outside the home. Children in the intervention arm of this trial underwent a home survey for hazards and their parents were educated about hazard exposure amelioration and were given coupons to purchase safety devices (including car seats and bicycle helmets). This trial found that the intervention was effective in reducing the overall occurrence of injury visits (inside and outside the home) at 4 months of follow-up (7 vs.11% between intervention and controls, p<0.05) and the rate ratio of self-reported injury between intervention and control groups (rate ratio 0.75, 95%CI 0.58, 0.96 per person-year of follow-up) at 12-months. However, they concluded that a single home visit was insufficient to influence the long-term adoption of home safety measures. Home safety modifications were present in less than 15% of intervention homes (2 of 16 safety modifications measured). A follow-up report at 36 months showed a persistence of improvement in parental safety knowledge and a significant but declining effect on self-reported doctor visits for injury in intervention compared with control households (rate ratio 0.80, 95%CI 0.64, 1.00).24

In a larger controlled trial in the United Kingdom (UK), Watson and colleagues randomized more than 3400 families in 47 general practices in Nottingham to receive a standardized safety consultation and provision of free and fitted stair gates, fire guards, smoke alarms, cupboard locks, and window locks for low income families and reduced cost equipment to families with relatively higher income.8 Control families received usual care. A total of 1163 (68%) families in the intervention arm received safety counseling, 619 (36%) had free equipment fitted, and 26 (1.5%) bought equipment at low cost. Primary outcome measures included whether a child younger than 5 years in the family had at least one medically attended injury, rates of attendance in primary and secondary care, and hospital admission over a 2-year follow up period. Paradoxically, the attendance rate for a medically-attended injury visit was 37% higher for children in the intervention compared to control arms (p=0.003).

There are important differences in the study design and interventions of these prior trials that make it difficult to compare directly to this study. The mutlicenter study, conducted by King, et.al., included older children up to 8 years of age, interventions outside the indoor environment (e.g. bicycle helmets and child automobile seat restraints), and did not install the safety products. In the second, UK study, that showed an increase in injury rates in the intervention group, only about a third of families randomized to the intervention arm actually had safety products installed and differences in safety practices from baseline to 12 and 24-month follow-up for all intervention and control families were small (<10% for most practices). Also, this study measured all medically attended injuries in children younger than 5 years (as opposed to hazards and mechanisms directly related to the products provided or ‘fitted’), possibly diluting the ability to measure the maximal effect of the intervention on modifiable injuries among younger children. Although these investigators did not find a significant interaction of randomized group status with child age, other investigators have found age to be a significant risk factor for injury in the home environment. 25, 26 Thus, while we found differences in effect size and direction of effect with these two studies, there were important differences in the design, populations of children enrolled, and interventions which make them difficult to compare with this study.

There were several limitations of the current study. First, it is not possible to conduct a double-blind trial for this type of study. Nevertheless, while the participants were not masked to group assignment, research interviewers who assessed medically attended injuries by telephone were blinded to group assignment. Furthermore, intervention technicians performing installation and maintenance visits were not used as research interviewers and were maintained as separate, functioning teams throughout the study. Second, we relied on maternal report of injuries. However, we verified parental report using a county-wide surveillance system for emergency visits. Third, although mothers participating in this study were representative in age and racial background of those who gave birth in the 5 county region from which they were enrolled, this sample of children and their families may not be representative of U.S. households.

The installation of multi-faceted home safety devices led to a significant reduction in injury hazards and a 70% in medically-attended and modifiable injury among children in the first 2 years of life. Healthcare expenditures for injury in US children amount to more than $2.3 billion annually and emergency visits for children due to injury cost on average about $800 per visit.19, 27 As US children younger than 5 years account for more than 1.7 million emergency visits and 5 million ambulatory visits annually for injury in the home environment1, 19, 28, this intervention, if replicated in larger populations of mothers and their children, could reduce pain and suffering and save millions of dollars in healthcare costs.

Figure 2.

Intention-to-Treat Analysis of Medically Attended Injury

Acknowledgements

Funding / support: Dr. Lanphear, Phelan received support from the National Institutes of Health (National Institutes of Environmental Health and National Institute for Child Health and Development) and Dr. Phelan from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the US Centers for Disease Control. Dr. Lanphear also received funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Role of the Sponsors: Funding organizations reviewed the initial designs and protocols on a blinded, competitive peer-reviewed basis to determine funding based upon design and scientific merit but had no role in data collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or write-up of the results.

K. Phelan supported by: 1K23HD045770-01A2 Career Development Award from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) and a New Investigator Award from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the CDC: R49CCR523141-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development, the US Centers for Disease Control, or the National Institutes of Health.

B. Lanphear supported by: US Environmental Protection Agency (PO1-ES11261) and the National Institutes for Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES014575).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs. Lanphear, Phelan, Khoury, Hornung, and Ms. Xu had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data an accuracy of the data analysis.

Study Design and Concept: Dr. Phelan, Lanphear, Khoury, Hornung

Acquisition of data: Dr. Phelan, Lanphear, Ms. Liddy

Analysis and interpretation of data: Dr. Phelan, Lanphear, Khoury, Xu, Hornung

Drafting of the manuscript: Dr. Phelan, Lanphear, Khoury, Xu, Liddy, Hornung

Critical revision of the manuscript for improtant intellectural content: Dr. Phelan, Lanphear, Khoury

Statistical analysis: Dr. Phelan, Lanphear, Khoury, Xu, Hornung

Obtained funding: Dr. Phelan and Lanphear

Administrative, technical, or material support: Dr. Phelan, Lanphear, Khoury, Xu

Study Supervision: Dr. Phelan, Lanphear, Khoury, Ms. Liddy and Xu

Financial Disclosures: none

Presented at the Pediatric Academic Society Meetings, Vancouver, Canada, May 3, 2010 and at the World Safety Conference in London, UK, September, 2010.

NIH Trial Registration (www.clinicaltrials.gov): NCT00129324

References

- 1.Phelan KJ, Khoury J, Kalkwarf H, Lanphear B. Residential injuries in U.S. children and adolescents. Public Health Rep. 2005 Jan-Feb;120(1):63–70. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman SJ, Schnare AB. Subsidizing Shelter - The Relationship between Welfare and Housing Assistance. Urban Institute; Washington, D.C.: 1988. pp. 88–1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen E, Matthews KA, Boyce WT. Socioeconomic Differences in Children’s Health: How and Why Do These Relationships Change with Age? Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128(2):295–329. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholer SJ, Hickson GB, Ray WA. Sociodemographic factors identify US infants at high risk of injury mortality. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1183–1188. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelan K, Khoury J, Atherton H, Kahn RS. Maternal depression, child behavior, and injury. Inj Prev. 2007 Dec;13(6):403–408. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.014571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwebel DC, Brezausek CM. Chronic maternal depression and children’s injury risk. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008 Nov-Dec;33(10):1108–1116. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kendrick D, Coupland C, Mulvaney C, et al. Home safety education and provision of safety equipment for injury prevention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005014.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson M, Kendrick D, Coupland C, Woods A, Futers D, Robinson J. Providing child safety equipment to prevent injuries: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;22(330(7484)) doi: 10.1136/bmj.38309.664444.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gielen AC, Wilson MEH, McDonald EM, et al. Randomized Trial of Enhanced Anticipatory Guidance for Injury Prevention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:42–49. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gielen AC, McDonald EM, Wilson MEH, et al. Effects of Improved Access to Safety Counseling, Products, and Home Visits on Parents’ Safety Practices - Results of a Randomized Trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:33–40. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phelan K, Khoury J, Xu Y, Lanphear B. Validation of a HOME Injury Survey. Injury Prevention. 2009;15:300–306. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.020958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phelan KJ, Khoury JC, Kalkwarf HJ, Lanphear BP. Residential Injuries in US Children and Adolescents. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(1):63–70. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson M, Kendrick D, Coupland C. Validation of a home safety questionnaire used in a randomised controlled trial. Inj Prev. 2003 Jun;9(2):180–183. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.2.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greaves P, Glik D, Kronenfeld JJ, Jackson K. Determinants of controllable in-home child safety hazards. Health Educ Res. 1994;9(3):307–315. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glik DC, Greaves P, Kronenfeld J, Jackson K. Safety Hazards in Households with Young Children. J. Pediatr. Psych. 1993;18(1):115–131. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/18.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omar RZ, Thompson SG. Analysis of a cluster randomized trial with binary outcome data using a multi-level model. Stat Med. 2000 Oct 15;19(19):2675–2688. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001015)19:19<2675::aid-sim556>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bishai D, McCauley J, Trifiletti LB, et al. The burden of injury in preschool children in an urban medicaid managed care organization. Ambul Pediatr. 2002 Jul-Aug;2(4):279–283. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0279:tboiip>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagaraja J, Menkedick J, Phelan KJ, Ashley P, Zhang X, Lanphear BP. Deaths from residential injuries in US children and adolescents, 1985-1997. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):454–461. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danseco E, Miller TR, Spicer RS. Incidence and Costs of 1987-1994 Childhood Injuries: Demographic Breakdowns. 2000;105(2):2000. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.e27. http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/105/2/e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendrick D, Barlow J, Hampshire A, Stewart-Brown S, Polnay L. Parenting interventions and the prevention of unintentional injuries in childhood: systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2008 Sep;34(5):682–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posner JC, Hawkins LA, Garcia Espana F, Durbin DR. A randomized, clinical trial of a home safety intervention based in an emergency department setting. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1603–1608. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kendrick D, Barlow J, Hampshire A, Polnay L, Stewart-Brown S. Parenting interventions for the prevention of unintentional injuries in childhood. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006020. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006020.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King W, Klassen T, LeBlanc J, et al. The Effectiveness of a Home Visit to Prevent Childhood Injury. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):382–388. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King WJ, LeBlanc JC, Barrowman NJ, et al. Long term effects of a home visit to prevent childhood injury: three year follow up of a randomized trial. Inj Prev. 2005 Apr;11(2):106–109. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.006791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrongiello BA, Klemencic N, Corbett M. Interactions between child behavior patterns and parent supervision: implications for children’s risk of unintentional injury. Child Dev. 2008 May-Jun;79(3):627–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrongiello BA, Cusimano M, Orr E, et al. School-age children’s safety attitudes, cognitions, knowledge, and injury experiences: how do these relate to their safety practices? Inj Prev. 2008 Jun;14(3):176–179. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.016782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens PL, Zodet MW, Berdahl T, Dougherty D, McCormick MC, Simpson LA. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: focus on injury-related emergency department utilization and expenditures. Ambul Pediatr. 2008 Jul-Aug;8(4):219–240. e217. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schappert SM, Burt CW. Ambulatory care visits to physician offices, hospital outpatient departments, and emergency departments: United States, 2001-02. Vital Health Stat 13. 2006 Feb;(159):1–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]