Abstract

Selective conservative therapy has not gained popularity in the management of abdominal gunshot wounds, and standard practice is mandatory exploration irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms. In this report, we describe a 10-year-old boy with an abdominal gunshot wound with stable vital signs who was managed conservatively.

Keywords: Gunshot, Nonoperative management

Introduction

Gunshot wounds to the anterior and posterior abdomen have been traditionally managed by mandatory exploration [1]. The policy of selective conservatism in gunshot wounds of the abdomen has been proposed in selected patients because of the incidence of negative laparotomy which ranged from 11 to 15 % [2]. In this case report, we aim to emphasize that not every gunshot injury needs a laparotomy.

Case Report

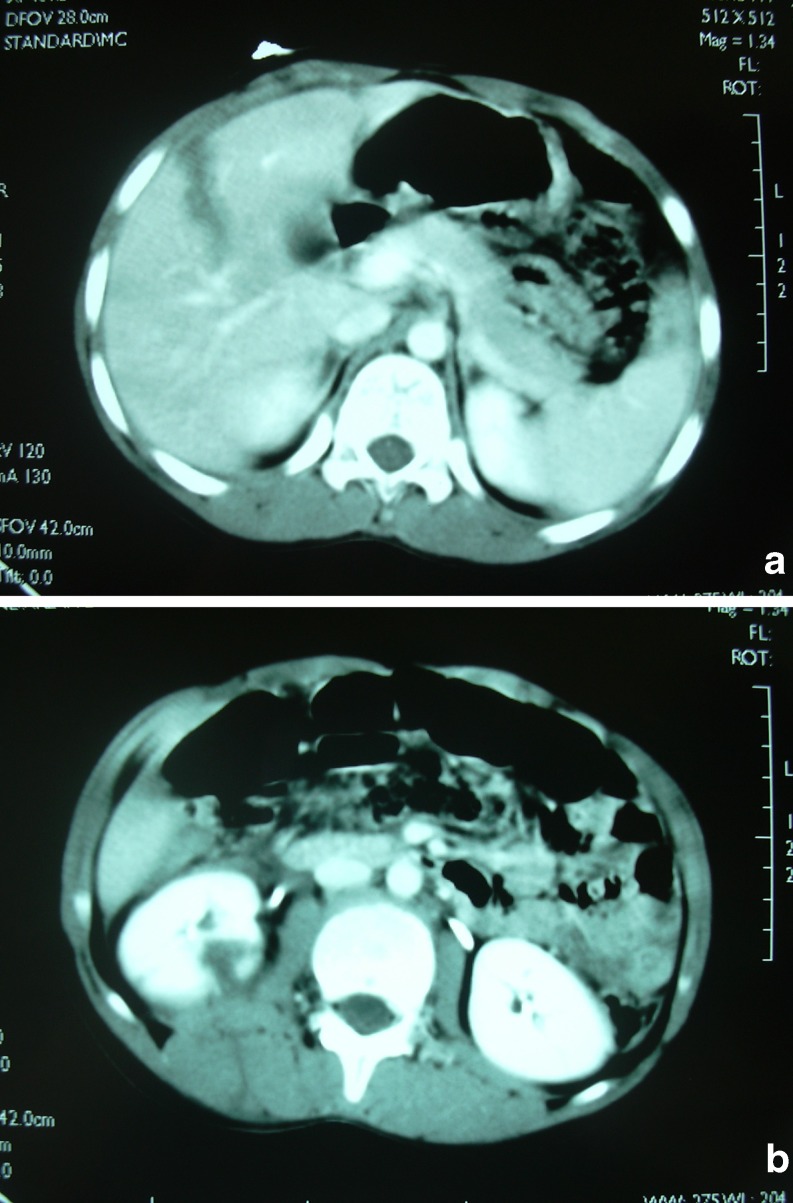

A previously healthy 10-year-old boy presented to our hospital after a gunshot wound to the right lumbar area near the vertebral column. No existing wound was identified. Initial vital signs revealed a heart rate of 100 beats/min and blood pressure of 90/50 mmHg. The right upper and lower abdomens were tender. On the right lumbar area at the level of L2, there was a bullet entry. The hemoglobin level was 12.4 g/dl and white blood cell count was 19,400 103/μl. Chest X-ray revealed no pathology, and no free air was detected on the upright abdominal X-ray. The bullet could be identified at the right side of L2 (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) scanning performed after contrast media ingestion revealed a laceration of the right hepatic lobe (Fig. 2a) and right lower renal pole, fracture of processus transversus of L2 and also a hematoma in the psoas muscle and perirenal area and additionally free air (Fig. 2b). No intestinal contrast leakage was observed on late follow-up scan. Intravenous fluids, tetanus toxoid, and second-generation cephalosporin antibiotic were administered. This patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. In this unit, blood pressure monitoring, pulse rate, serial hemoglobin, oxygen saturation, and repeated abdominal examinations were routinely performed on this patient. Control Hb levels of the patient were not lower than 12 g/dl. The patient recovered well and was discharged on the sixth day of hospital admission.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal X-ray shows no free air or bullet

Fig. 2.

CT scan shows a laceration of the right hepatic lobe (a) and right lower renal pole, fracture of processus transversus of L2 (b)

Discussion

Valentine and Dawidson stated that exploratory laparotomy should be performed in all gunshot injuries of the abdomen. But Demetriades suggest that carefully selected patients with gunshot injury of abdomen can be safely managed nonoperatively [3]. In a prospective study of 146 patients, 28 % of the patients were observed and 7 of them required subsequent operation without any serious consequences [3]. Several methods to support clinical examination were utilized in the nonoperative follow-up period of gunshot injuries. Boyle and Brakenridge suggested that in stable patients a diagnostic peritoneal lavage should be performed as an initial diagnostic study [4, 5]. When the peritoneal lavage is negative, triple-contrast (intravenous, oral, and rectal) CT should be performed [6]. In different series, the sensitivity and specificity of triple-contrast CT scanning was found to be 97 and 98 % [7].

Nonoperative management of gunshot injuries in adults is widely used, but the number of pediatric cases is limited. This case report shows that a conservative approach in selected pediatric cases can be applied if staff and facility are sufficient and radiological support is available. Consequently, negative laparotomy and morbidity rates can be reduced.

References

- 1.Velmahos GC, Demetriades D, Cornwell EE., III Transpelvic gunshot wounds: routine laparotomy or selective management? World J Surg. 1998;22:1034–1038. doi: 10.1007/s002689900512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dokucu AI, Otcu S, Ozturk H, Onen A, Ozer M, Bukte Y, et al. Characteristics of penetrating abdominal firearm injuries in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2000;10:242–247. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1072367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demetriades D, Charalambides D, Lakhoo M, Pantanowitz D. Gunshot wound of the abdomen: role of selective conservative management. Br J Surg. 1991;78:220–222. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle EM, Jr, Maier RV, Salazar JD, Kovacich JC, O’Keefe G, Mann FA, et al. Diagnosis of injuries after stab wounds to the back and flank. J Trauma. 1997;42:260–265. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199702000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brakenridge SC, Nagy KK, Joseph KT, An GC, Bokhari F, Barrett J. Detection of intra-abdominal injury using diagnostic peritoneal lavage after shotgun wound to the abdomen. J Trauma. 2003;54:329–331. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000037292.17482.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozturk H, Otcu S, Onen A, Dokucu AI. Retroperitoneal organ injury caused by anterior penetrating abdominal injury in children. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003;10:164–168. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, Chiu WC, Killeen KL, Hogan GJ, Scalea TM. Penetrating torso trauma: triple-contrast helical CT in peritoneal violation and organ injury a prospective study in 200 patients. Radiology. 2004;231:775–784. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2313030126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]