Abstract

Although fibromatosis of the mesentery is a very rare locally aggressive benign condition, the uncertain treatment modalities, the natural history of the disease, and the other common differential diagnosis of the condition along with inexperience of the general clinicians with this disease pose a challenge to the professionals. The prolonged periods of stability and even regression in size of the tumor offer a hope for treatment. Accounting for 0.03 % of all neoplasms, it is also known as deep fibromatosis and desmoid tumor. Here, we discuss one case of primary mesenteric fibromatosis in a young male patient who presented to us with chronic abdominal pain after he was treated for acid peptic disease for the same at a local hospital. This case shows how management of this disease can be delayed due to unfamiliarity among clinicians of this condition. In our patient, a palliative surgical management plan was undertaken due to symptomatic mass in the abdomen, owing to unresectability.

Keywords: Mesentery, Mesenteric tumors, Fibromatosis, Desmoid tumors, Gardner’s syndrome

Introduction

Fibromatosis of the mesentery is a rare benign condition with a tendency to spread locally. With its long natural course of history and vague symptoms, patients with this condition often present late. Primary or spontaneous fibromatosis is rare [1, 2] and secondary most commonly occurring after trauma [3]. The etiology is unknown, but an endocrine cause is suggested in case of primary condition [4], commonly originating from the musculoaponeurotic structures of the body [5]. These tumors can show prolonged periods of stability and even regression in size [6]. An association with astrocytomas [4], Gardner’s syndrome [7, 8], and familial colonic polyposis has been reported. With a wide range of differential diagnosis, this condition poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to the clinician.

Case Discussion

A 45-year-old man presented with history of abdominal pain, occasional vomiting, and loss of appetite for a period of 2 months with generalized weakness and mild fever on and off. There was no history of any obstruction or bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract. On examination there was a firm mass in the lower portion of epigastrium. Investigations revealed a raised ESR and leucocytosis. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed erosive gastritis. Abdominal ultrasonogram showed a mass arising from omentum with increased vascularity, with a vascular pedicle from mesentery. With a provisional diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis, the patient was posted for laparotomy. At laparotomy a firm mass measuring 10 cm × 12 cm, arising from the root of mesentery encasing the origin of superior mesenteric vessels, was identified. In view of encasement of superior mesenteric vessels, no attempt was made to excise it. Biopsy was taken, reported as mesenteric fibromatosis. Further evaluation of the patient was carried out to rule out Gardner’s syndrome. Skull radiographs were normal. The patient was started on tamoxifen 20 mg OD. After 1 month, the patient presented with features suggestive of upper GI obstruction; barium meal radiograph showed obstruction of the third part of the duodenum. CT scan showed a large enhancing homogeneous mass encasing the superior mesenteric vein and causing obstruction of the duodenum, along with paraaortic lymphadenopathy. A second laparotomy was planned and palliative duodenojejunostomy was done. Postoperatively after 5 months, the patient is doing well. He is currently on tamoxifen 20 mg OD (Fig. 1).

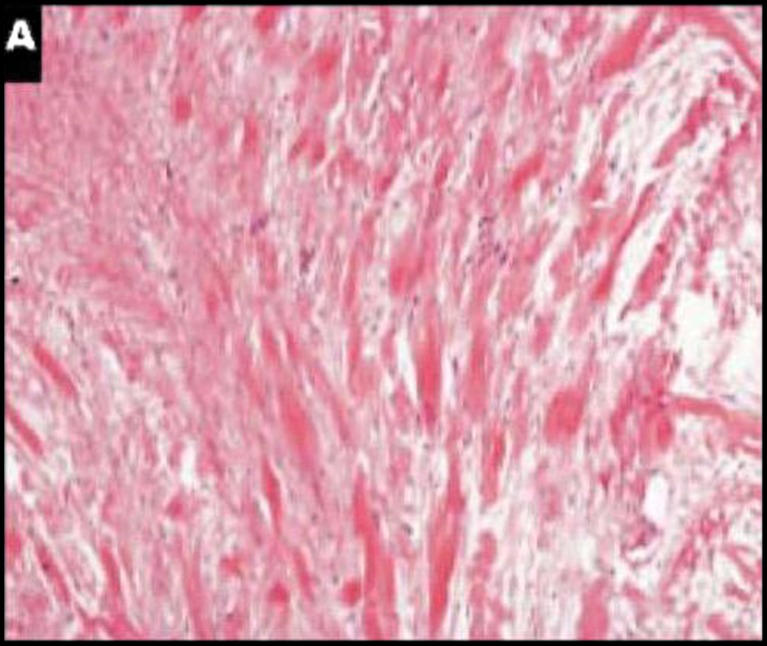

Fig. 1.

a Mesenteric fibromatosis (MF). Note the homogeneous and low-density cellularity and thin-walled, dilated veins (H&E, ×100). b High-power view of a field displaying cytologic characteristics of MF, with stellate fibroblasts, plump nuclei, and micronucleoli (H&E, ×400)

Discussion

Mesenteric fibromatosis accounts for 0.03 % of all neoplasms [1]. The etiology is unknown, but an endocrine cause has been suggested. The disease is more prevalent in perinatal women and tumor has shown regression after the menopause. The male-to-female ratio of the disease is 4:1 [2]. Significant amount of estradiol has been found in tumor cytosol, and tumor has shown regression with tamoxifen therapy. There is an evidence that fertile female patients with desmoid tumor have estrogen dominance, and tumor has shown a direct relationship between the growth rate and the level of endogenous estrogen [3].

It often is asymptomatic, and weight loss with a palpable tumor is common in a large tumor. Isolated cases are reported with patients presenting as pyrexia of unknown origin (with a raised C-reactive protein) [1] to ureteric obstruction and involvement of mesenteric vessels [6] to vague abdominal symptoms. The differential diagnosis for mesenteric fibromatosis includes GIST, lymphomas, carcinoids, fibrosarcomas, and inflammatory fibroid polyps [4]. Microscopic features include spindle, wavy cells lacking atypia associated with deposition of abundant collagen. Most common differential diagnosis would be a GIST which can be differentiated by a positive CD 34 staining [3] and β-catanin [4] in case of GIST (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

a Prominent collagen fibers typically are seen in mesenteric fibromatosis cases (H&E, ×250)

As radiological findings are indefinitive, a surgical approach is required for diagnostic purposes to take a biopsy by a laparoscopy or by a laparotomy, resection of the tumor if possible, or a palliative surgery in a symptomatic patient with unresectable tumors. Although the preferred treatment is local surgical resection with a margin of uninvolved tissue, one study [6] showed no survival difference between resected and unresected patients, noting that some tumors have prolonged periods of stability or even regression. When a radical surgery fails or the tumor is unresectable, radiation [5, 6], chemotherapy [7] with dactinomycin, vincristine, and cyclophosphamide, or hormonal therapy [8] with progesterone and testosterone has also been used with temporary results.

In our patient, laparotomy was done and as the tumor was unresectable, a biopsy was taken and abdomen was closed as the patient did not have major symptoms other than mild abdominal pain. After confirming the diagnosis from the histopathological report, the patient was started on tamoxifen therapy (20 mg OD). The patient was evaluated radiologically for the probable associated syndrome conditions and proved to have none. One month after diagnostic laparotomy, the patient developed intestinal obstruction in the proximal bowel for which a palliative bypass surgery was carried out. Postsurgery he is being continued on tamoxifen therapy. He is doing well after 6 months of diagnosing the disease.

References

- 1.Burke AP, Sobin LH, Shekitka KM, Federspiel BH, et al. Intra-abdominal fibromatosis: a pathological analysis of 130 tumors with comparison of clinical subgroups. Am J Path. 1990;12:335–341. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim DH, Goldsmith HS, Quan SH, Huvos AG, et al. Intra-abdominal desmoids tumor. Cancer. 1971;27:1041–1045. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197105)27:5<1041::AID-CNCR2820270506>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reitamo JJ, Scheinin TM, Häyry P. The desmoid syndrome. New aspects in the cause, pathogenesis and treatment of the desmoid tumor. Am J Surg Feb. 1986;151(2):230–237. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bethune R, Amin A. Mesenteric fibromatosis: a rare cause of acute abdominal pain. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:1–2. doi: 10.1308/147870806X95212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah M, Azam B. Case report of an intra-abdominal desmoid tumor presenting with bowel perforation. McGill J Med. 2007;10(2):90–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith AJ, Lewis JJ, Merchant NB, Leung DH, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Surgical management of intra-abdominal desmoid tumors. Br J Surg. 2000;87:608–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner EJ. A genetic and clinical study of intestinal polyposis, a predisposing factor carcinoma colon and rectum. Am J Hum Genet. 1951;3:167–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner EJ. Follow-up study of a family group exhibiting dominant inheritance for a syndrome including intestinal polyps, osteomas, fibromas and epidermal cysts. Am J Hum Genet. 1962;14:376–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]