Abstract

Introduction

Bezoars are uncommon findings in the gastrointestinal tract and are composed of a wide variety of materials. Large metal bezoars are very rare with only a few case reports till date in literature. We report a case of a metal bezoar in a man with Maniac Depressive Psychosis who had a history of ingesting Nails and screws of sizes varying from 2 cm to 15 cm for more than 1 year without causing any perforation and other acute complication.

Case presentation

A 24-year-old man presented with a history of mild dull aching type of abdominal pain of chronic onset and no other GI symptoms. The patient had history of passing small sized nails in the stools and intermittent melena for last 1 year. Physical examination revealed mild tenderness in Para umbilical region. Past medical history was remarkable for treatment of Maniac depressive psychosis. Plain radio graphs revealed objects of metal density contained within a dilated stomach at the level of L2–3 vertebrae in the midline. Celiotomy was performed and 27 metal nails and screws of sizes 6 cm to 15 cm and bent in various shapes were removed from inside the stomach. Post operatively patient recovery was normal and he was referred to psychiatrist.

Conclusion

Abdominal pain in patients with psychiatric disorders can result from rare causes such as bezoars and such bizarre metal nails without causing any acute abdominal symptoms. This report alerts surgeons to rule out bezoars in the differential diagnosis of chronic abdominal pain and melenic stools with no abdominal symptoms in patients with psychiatric health problems.

Keywords: Bizarre, Metal, Bezoars, Nails and screws

Introduction

A bezoar is a conglomeration of partially digested or nondigested foreign material in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, most commonly found in the stomach [1]. Less commonly, bezoars are found in the small intestine and the colon, and only a few in the rectum are reported in the literature [2]. Bezoars may cause a wide variety of signs and symptoms, depending on their location, and can range from asymptomatic to occlusion and perforation. Bezoars are classified into several main types and are named according to the materials from which they are composed: phytobezoars, trichobezoars, pharmacobezoars, and lactobezoars. Other rare, less frequent bezoars are unclassified and include materials such as plastic and metal.

The occurrence of relapse is rare and will reappear in 14 % of cases, more often associated in psychiatric patients [3]. Only few cases of metal bezoars have been reported in the international literature [4, 5].

Case Presentation

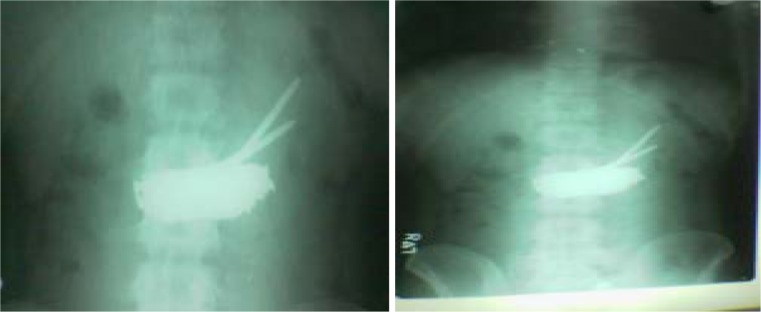

A 24-year-old man presented to the surgical outpatient department room with chronic onset of mild diffuse abdominal pain and history of passing intermittent melenic stools and passing metal fragments in stools for the last 1 year. There was no history of any acute pain and vomiting. His social history was significant for smoking and alcohol intake. He also had history of taking psychiatric treatment for maniac depressive psychosis. Physical examination revealed an afebrile patient with mild tachycardia and mild pallor. The abdomen was soft and tender in the paraumbilical region only on deep palpation without any signs of acute abdomen. No other positive findings were found in abdominal examination. Rectal examination revealed nothing abnormal. Laboratory tests revealed low hemoglobin and all other tests (cell counts, renal function tests, liver function tests, serum electrolytes and blood gases) were unremarkable. Plain radiographs (anteroposterior) of the abdomen showed a large metal density shadow in the midabdomen with multiple pointed projections of different sizes towards left side (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Plain radiograph (anteroposterior) of the abdomen showing multiple objects of metal density contained within the stomach

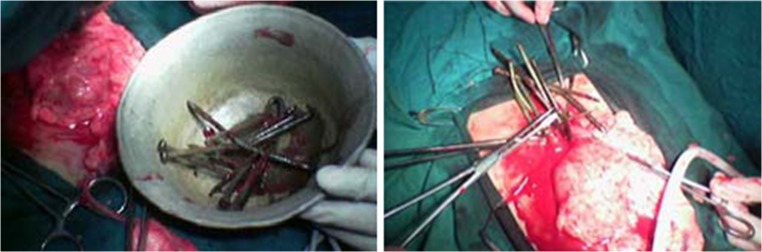

The patient was taken to the operating room (OR) for an exploratory celiotomy through a midline incision. He was found to have a mildly distended stomach with palpable metal nails in it. A longitudinal gastrotomy was made, revealing multiple metal nails of various sizes and bent in various shapes. A total of 27 nails of varying in size from 5 to 15 cm were removed (Fig. 2). After emptying the stomach, it was closed with a double layer suture in a custom fashion, leaving in place a nasogastric tube for gastric drainage. Before closing the abdomen, a complete exploration of the small and large bowel was made to avoid remnants of metal particles to prevent any postoperative complication. Postoperative recovery was uneventful. The patient was discharged and transferred to a psychiatric facility 8 days after the surgery. A 6-month follow-up showed no recurrence or any postoperative complication.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative objects obtained from the stomach

Discussion

Bezoars are classified according to the materials they are composed of (named in order of frequency): Phytobezoars made of vegetable fibers or plant material, trichobezoars are a result of ingestion of human hair, drug bezoars contain accumulated masses of medication, lactobezoars made of undigested milk described in premature infants and in full-term infants and other less-frequent materials are named miscellaneous bezoars or polybezoars [6]. GI bezoars are uncommon and are reported to occur in 4 % of all admissions for small-bowel obstruction [7]. Reports of bezoars causing obstruction of the GI tract have existed since the late 18th century. Around 400 cases of trichobezoars and a large number of phytobezoars have been reported in the literature [8]. After reviewing the literature, we found only two previous reports on metal bezoars, the first by Salb [4] in 1956 and the second reported by Kaplan et al. [5] in 2005, none being relapsing or massive. Since approximately 10 % of patients show psychiatric abnormalities or mental retardation [8], psychiatric evaluation and therapy are needed to prevent recurrence [9].

This entity occurs in the normal stomach, caused by the ingestion of materials, such as plastic, metal, and wooden foreign bodies, that cannot pass the pylorus. Other bezoars occur as a complication of gastric motility, usually prior gastric surgery such as vagotomy, leading to reduced gastric acidity; gastric stasis and loss of pyloric function; peptic ulcer disease/stenosis; chronic gastritis; Crohn’s disease; carcinoma of the stomach, duodenum, or pancreas; dehydration and hypothyroidism [10]; and diabetic patients with neuropathy or myotonic dystrophy [11]. Also to be considered is the fact that certain medications, such as anticholinergic agents, ganglionic blocking agents, and opiates, that decrease GI motility may also give rise to a bezoar [10]. With time, undigested foreign bodies are retained by mucus and become enmeshed, creating a mass in the shape of the stomach where they are usually found. They may attain large sizes owing to the chronicity of the problem and delayed reporting by the patients [12].

Bezoars have been known to cause a wide variety of symptoms. In the stomach, they are associated with anorexia, bloating, early satiety, dyspepsia, malaise, weakness, weight loss, headaches and a feeling of fullness or heaviness in the epigastrium [13]. They may also present with GI bleeding (6 %) and intestinal obstruction or perforation (10 %) [14]. GI bezoars can be easily diagnosed in most patients. Plain X-rays, like the radiograph in our patient, are unique and lead to the diagnosis. However, diagnostic difficulties arise in patients with radiolucent bezoars, and contrast studies of the GI tract by radiography and computed tomography scan are necessary in such circumstances. Upper GI endoscopy is the method of choice in detecting esophageal, gastric and duodenal foreign bodies. Occasionally, bezoars are found incidentally when an emergency laparotomy is done secondarily to bowel obstruction. Several treatments have been proposed for bezoars, and they depend on the clinical presentation as well as on the composition of the bezoar. Chemical and enzymatic compounds have been used for dissolution of esophageal and gastric phytobezoars and lactobezoars [15]. For small bezoars, endoscopy has been the treatment of choice. Once the obstruction occurs, surgery is the only way to solve the problem. Frequently, synchronous bezoars are found in the stomach or other areas of the GI tract; therefore, it is mandatory to carry out a thorough exploration of the small intestine and colon [11] to avoid recurrence of intestinal obstruction due to a retained bezoar. After discharge, recurrence has been reported in up to 14 % of cases, especially in patients with psychiatric disturbances and with previous gastric surgery [3].

Conclusion

In our Patient, the diagnosis was simple and clear after the plain X-Rays and the history given by the patient. The gastrotomy with foreign material removal and thorough exploration of the rest of the GI tract was curative. We conclude that in Psychiatric Patients with history of even mild abdominal pain, abdominal X-rays must be done and not be ignored as insignificant of functional.

Plain and contrast-enhanced radiographic studies are important for both diagnosis and treatment. It is also important to consider GI endoscopy as part of the diagnosis and treatment plan. In cases where bezoars cannot be treated by dissolving agents such as enzymes or chemicals and endoscopy is not able to remove the obstruction, surgery is the last option.

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Davis RN, Rettmann JA, Christensen B. Relapsing altered mental status secondary to a meprobamate bezoar. J Trauma. 2006;61:990–991. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000240253.94361.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg JM, Eitan A. Prickly pear fruit bezoar presenting as rectal perforation in an elderly patient. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:365–367. doi: 10.1007/s00384-003-0482-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robles R, Parrilla P, Escamilla C, Lujan JA, Torralba JA, Liron R, Moreno A. Gastrointestinal bezoars. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1000–1001. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salb RL. Metallic bezoar. Med Radiogr Photogr. 1956;32:32–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan R, Celebi F, Guzey D, Celik AS, Erozgen F, Firat N. Medical image. Metal bezoar. N Z Med J. 2005;118(1219):U1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall JD, Shami VM. Rapunzel’s syndrome: gastric bezoars and endoscopic management. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho TW, Koh DC. Small-bowel obstruction secondary to bezoar impaction: a diagnostic dilemma. World J Surg. 2007;31:1073–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0619-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma RD, Kotwal S, Chintamani BD. Trichobezoar obstructing the terminal ileum. Trop Doct. 2002;32:99–100. doi: 10.1177/004947550203200217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuroki Y, Otagiri S, Sakamoto T, Tsukada K, Tanaka M. Case report of trichobezoar causing gastric perforation. Dig Endosc. 2000;12:181–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1443-1661.2000.00023.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Fountain J. Could your patient’s bowel obstruction be a bezoar. Today Surg Nurse. 1999;21:34–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos RR, Paricio PP, Albasini JLA. Gastrointestinal bezoars. Presentation of 60 cases. Dig Surg. 1990;7:39–44. doi: 10.1159/000171939. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chintamani DR, Singh JP, Singhal V. Cotton bezoar—a rare cause of intestinal obstruction: case report. BMC Surg. 2003;4:3–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein SS, Lewis JH, Rothstein R. Intestinal obstruction due to bezoars. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:313–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrus CH, Ponsky JL. Bezoars: classification, pathophysiology, and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:476–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta R, Share M, Pineau BC. Dissolution of an esophageal bezoar with pancreatic enzyme extract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:96–99. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.115318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]