Abstract

Malignant triton tumor (MTT) is a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. This rare tumor, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature, generally affects adult patients with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1). We report such a case in a 34-year-old man with NF-1 who presented with a mass over the medial side of the arm. Histopathologically finding of rhabdomyoblasts among malignant Schwann cells in a tumor arising from a peripheral nerve supported by immunostaining with S-100 protein and myogenin confirmed the diagnosis. MTT has a poor prognosis owing to its aggressive biological behavior. The fact that this tumor is extremely rare has prompted us to report this case.

Keywords: Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), Malignant triton tumor (MTT), Neurofibromatosis-1 (NF-1), S-100 protein

Introduction

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) accounts for about 5–10 % of all soft tissue sarcomas [1]. Malignant triton tumor (MTT) is a subtype of MPNST characterized by the presence of rhabdomyosarcomatous elements in a background of schwannoma cells and constitutes about 5 % of all MPNSTs [1, 2].

Although MTT can present as a sporadic tumor, approximately 60–70 % occurs in young patients with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1) [3]. Diagnosis is confirmed based on morphologic grounds supported by an immunohistochemistry such as S-100 protein. Myo-D1 and myogenin are positive for rhabdomyoblasts [4]. MTT has an aggressive biological behavior; however, studies suggest that complete tumor resection with adjuvant therapy appears to improve survival [2, 3, 5].

Case Report

A 34-year-old man presented with a large mass on the medial side of the right arm for 14 years and had progressive left arm pain with reduced sensation of the left hand for 5 months. His family history suggested that his father was a diagnosed case of NF-1. On physical examination, the patient was found to be normal. There was a firm, nontender mass measuring approximately 6 cm located on the medial side of the left arm. There was no palpable axillary lymphadenopathy. He had café-au-lait spots and axillary freckling.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the right arm T1-weighted image showed an isointense mass on the medial aspect of the right arm in intermuscular plane measuring 6.0 × 4.8 × 3.8 cm (Fig. 1). The mass heterogeneously turned hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Fig. 2). On post contrast, a dense inhomogeneous enhancement of the mass was noted. Nonenhancing area suggested cystic changes/necrosis. The mass was abutting humorous medially and branchial vessels anteriorly; however, there was no evidence of erosion. A diagnosis of the neurogenic tumor was made and fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was advised.

Fig. 1.

MRT T1-weighted, showing mass on the medial aspect of the right arm

Fig. 2.

Intra-operative mass arising from axillary nerve

Multiple FNAC smears showed scanty bipolar cells in hemorrhagic background suggestive of the soft tissue tumor. With above investigations the patient was subjected for excision biopsy.

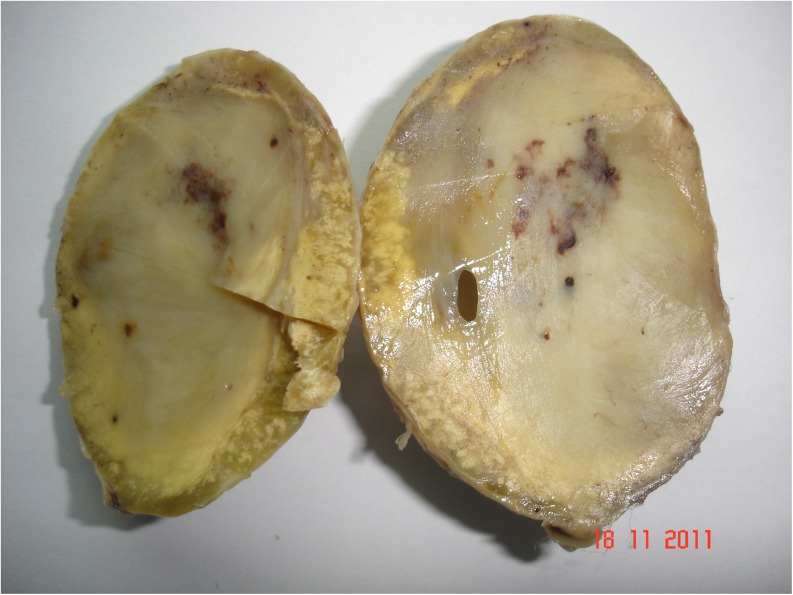

The resected mass consisted of a large globular well-encapsulated tumor measuring 7 × 5.5 cm. Outer surface is smooth, and cut surface is solid dull gray-white with specks of necrosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 3). Microscopy revealed alternate hypocellular areas composed of edematous stroma with cyst macrophages and hypercellular areas composed of spindle cells with the bipolar nucleus and nuclear palisading. The tumor also showed a good number of scattered large cells with severe hyperchromasia and pleomorphism with abundant deep eosinophilic cytoplasm. In a few areas, tumor giant cells were observed. Mitotic figures were 10–12/10 high-power fields with a few atypical mitoses (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

A cut section of solid tumor mass measuring 7 × 5.5 cm with specks of hemorrhage and necrosis

Fig. 4.

Microphotograph (hematoxylin and eosin), showing tumor with spindle cells having wavy nucleus and a few rhabdomyoblasts

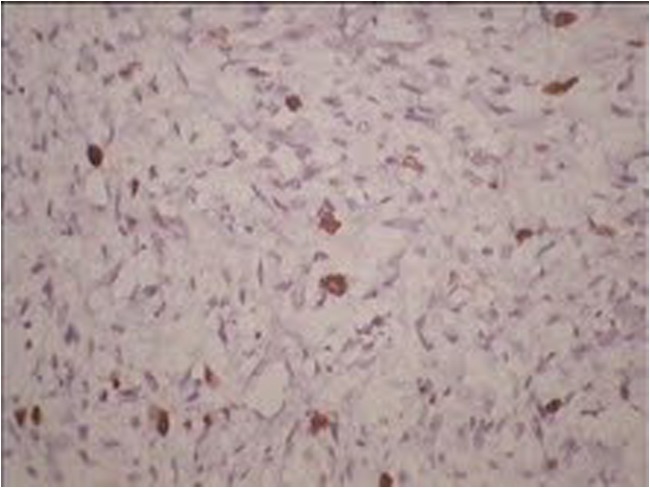

Immunohistochemical stains showed malignant cells positive for S-100 protein (Fig. 5) and myogenin (Fig. 6). The malignant cells were negative for smooth muscle actin (SMA), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), cluster of differentiation 31 (CD31), CD34. These immunohistologic findings established the diagnosis of MTT.

Fig. 5.

Microphotograph, showing tumor cells positive for S100

Fig. 6.

Microphotograph, showing tumor cells positive for myogenin

Discussion

MTT is a rare tumor with fewer than 100 cases documented in the literature. MTT is an interesting neurogenic tumor in which the neural component is thought to induce skeletal muscle production [6, 7]. This process was known to occur following Locatelli’s experiment with the Triton salamander, where he showed that by implanting a sciatic nerve in the salamander’s back, growth of accessory limbs containing both neural and muscular tissues could be stimulated [8]. Masson, in 1932, first described its malignant potential in the form of an MTT with Von Recklinghausen disease (NF-1) naming it after Locatelli’s Salamander [8, 9].

MTTs arise in association with NF-1 or can arise sporadically. Two third of the cases of MTTs have been reported in conjunction with NF-1 [4, 6, 7]. When it occurs in the sporadic form, other spindle cell sarcomas such as fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma can come as differential diagnosis [10]. MTTs with NF-1 are seen predominantly in males of younger age groups; on the contrary sporadic forms are seen in females of older age groups. The tumor develops after a long latent period of 10–20 years [1–3]. In our case, the tumor developed over a setting of NF-1 and developed after 14 years.

The tumor presents as a painful or painless firm enlarging mass in a variety of locations including the head and neck, extremities, trunk, buttock, visceras, retroperitoneum, and mediastinum [1, 3, 4]. Intracranial locations include the parieto-occipital lobe, lateral ventricle, and cerebellopontine angle [3]. They arise from large and medium nerves such as the sciatic nerve, spinal root, lumbosacral plexus, brachial plexus, and cranial nerves [4, 6, 7]. In our case, the patient had pain in the medial side of the left upper arm and the tumor arose from preexisting neurofibroma in his brachial plexus.

The diagnosis of MTT is usually made following surgical resection by histopathology supported by positivity for S-100 protein [4, 6]. The morphologic features are alternating hypocellular and hypercellular regions, the appearance of thin wavy comma-shaped/bullet-shaped nucleus in the hypocellular areas, presence of nuclear palisading, prominent thick-walled vasculature, and presence of rhabdomyoblasts. Such tumors show focal positivity for S-100 protein in 50–90 % of cases, suggesting a nerve sheath origin. Rhabdomyoblasts are positive for immunohistochemical stains such as desmin, myogenin, and myo-D1 [4, 11]. Our case was positive for S 100 and myogenin.

Recent works on cytogenetics have revealed some karyotypic changes associated with this tumor. There is a breakpoint in 11p15, considered a region of myogenic differentiation. This gene is probably responsible for rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. Amplification of c-myc oncogene is probably responsible for its aggressive biologic behavior [12, 13].

MTTs are tumors with a poor prognosis. The 5-year survival rate of MTT is only 5–15 % in contrast to MPNST where it is 50–60 % [2]. Modern treatment has improved the prognosis of such cases. Radical excision followed by high-dose radiotherapy is the conventional mode of treatment. Some recent reports suggest that neoadjuvant therapy and adjuvant chemotherapy can eradicate micrometastasis. Integrated positron emission tomography and computed tomography have been used to assess remission and response to therapy [5, 9]. The prognosis of MTT depends on the location, grade, and completeness of surgical margins. It is good for the head, neck, and extremities and worse for other sites including the buttock [5].

In conclusion, MTT is a rare neurogenic tumor with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation often associated with NF-1. Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry remains the mainstay of investigation to establish the diagnosis. Given the aggressive nature of the tumor with poor prognosis, radical excision followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy appears to improve survival.

References

- 1.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Malignant tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and weiss’s soft tissue tumors. 5. China: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. pp. 903–944. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks JSJ. Disorders of soft tissue. In: Sternberg SS, editor. Diagnostic surgical pathology. 3. Philadelphia: Lipincott Williams and Wilkins; 1999. pp. 131–221. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victoria L, McCulloch TM, Callaghan EJ, et al. Malignant triton tumor of the head and neck: a case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 1999;21:663–670. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199910)21:7<663::AID-HED12>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks JS, Freeman M, Enterline HT. Malignant triton tumors: natural history and immunohistochemistry of nine new cases with literature review. Cancer. 1985;55:2543–2549. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850601)55:11<2543::AID-CNCR2820551105>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang-Lazdunski L, Pons F, Jancovici R. Malignant triton tumor of the posterior medistinum: prolonged survival after radical resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1645–1648. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04825-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stasik CJ, Twafik O. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath with rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation (malignant triton tumor) Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1878–1881. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1878-MPNSTW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leroy K, Dumas V, Martin-Garcia N, et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors associated with neurofibromatosis type 1: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 17 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:908–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Locatelli P (1925) Formation de membres surnumeraires. CR Assoc Des Anatomistes 20e Reunion. Turin 279–282

- 9.Masson P. Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis. Sensory Neuromas and Motor Neuromas. New York: International Press; 1932. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aldlyami E, Dramis A, Grimer RJ, et al. Malignant triton tumor of the thigh – a retrospective analysis of nine cases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:808–810. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daimaru Y, Hashimoto H, Enjoli M. Malignant triton tumours. A Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of nine cases. Hum Pathol. 1984;15:768–778. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(84)80169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haddadin MH, Hawkins AL, Long P, et al. Cytogenetic study of malignant triton tumor: a case report. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003;144:100–105. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(02)00935-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strauss BL, Gutmann DH, Dehner LP, et al. Molecular analysis of malignant triton tumors. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:984–988. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]