Abstract

Primary intrarenal teratomas are uncommon, and their association with renal dysplasia is rarer. We report a case of primary renal teratoma in a 1-year-old child who had undergone a retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy. Pathologic examination showed evidence for a primary mature teratoma with renal dysplasia.

Keywords: Intrarenal teratoma, Renal dysplasia

Introduction

Primary renal teratomas are uncommon. A review of literature since 1915 shows less than 30 reports of primary intrarenal teratomas [1–5]. Intrarenal teratoma associated with renal dysplasia is an even rarer occurrence, with only two reported cases on record [2, 5]. We present here one such case of primary teratoma of the kidney occurring in a dysplastic kidney.

Case Report

A 1-year-old male child underwent a retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy for a nonfunctioning left kidney (8% differential function) with episodes of urinary tract infection and elevated blood pressure recordings. The child’s renal parameters were normal. Voiding cystourethrogram showed a primary grade 5 vesicoureteric reflux on the left side. Ultrasonography revealed a small-sized left kidney with gross hydronephrosis.

The kidney weighed 15 g and measured 3.5 × 1.5 × 1 cm. The external surface was lobulated and mildly congested (Fig. 1). Cut section showed gross thinning of renal parenchyma and marked dilatation of the superior calyceal system and the pelvis. The inner lining of the calyces was smooth; no nodule or thickening was noted.

Fig. 1.

Small-sized, nonfunctioning, hydronephrotic kidney

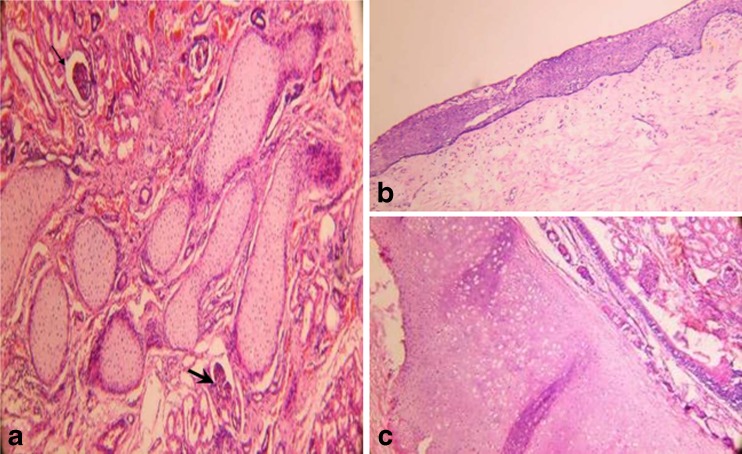

Microscopic sections showed foetal glomeruli and tubules with focally interspersed small-sized islands of metaplastic cartilage rimmed by scant, compressed fibrous stroma (Fig. 2a). One section contained a few cysts, some of which were lined by stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 2b) with fibroadipose tissue in the wall. A cyst was also present, lined by pseudostratified ciliated epithelium with lobules of hyaline cartilage and small groups of seromucinous glands in its wall, reminiscent of organoid tracheobronchial structures (Fig. 2c). The cysts were contained within the renal capsule. No immature elements were present.

Fig. 2.

Intrarenal teratoma (a) Islands of immature cartilage amidst renal tissue (arrows at glomeruli) (b) Squamous epithelial lining in a cyst (c) Bronchiolar structure-ciliated pseudostratified epithelium with underlying mucous glands and hyaline cartilage. (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, 40×)

Thus, a diagnosis of primary mature cystic teratoma associated with renal dysplasia was made.

The patient had an uneventful postoperative period. The blood pressure was normal with no urinary tract infections. Result for serum alpha-fetoprotein test, done postoperatively, was 8.7 ng/ml.

Detailed investigations have excluded the possibility of teratoma elsewhere in the body.

The child is on regular follow-up. He has had no local recurrence, and the latest serum alpha-fetoprotein levels are 3.1 ng/ml.

Discussion

Teratomas most commonly arise in the gonads, but have also been found in the anterior mediastinum, retroperitoneum, sacrococcygeal region, brain gastrointestinal tract and rarely in the kidney [1]. This diverse distribution is probably the result of the arrest of primitive germ cells during their migration from the yolk sac to the genital ridge. The proximity of the genital ridge to the nephrogenic anlage could explain how germ cells could be displaced into the kidney [6].

Primary intrarenal teratoma is an exceeding rarity with less than 30 cases reported [1–5]. The patients’ age ranged from 6 weeks to 71 years; a little more than half of these teratomas arose in children [1, 2]. The chief presenting symptoms included abdominal mass, abdominal pain, anorexia, vomiting, constipation and haematuria.

Although intrarenal teratomas are often quite large at presentation, they may be small and discovered incidentally [1]. Renal teratomas include both mature and immature types. Only two cases of renal teratoma in association with renal dysplasia have been published in literature [2, 5]. Renal teratomas associated with carcinoid tumour have also been reported. Associated congenital anomalies such as horseshoe-kidney, duplicated collecting system, etc. are occasionally seen [1, 2].

Congenital anomalies, in particular renal dysplasia, may suggest that intrarenal teratoma is associated with misdevelopment [7].

Differential diagnosis includes other cystic lesions such as multicystic renal dysplasia, hydronephrosis and infected renal cysts. Intrarenal teratoma must be differentiated from the rare teratoid variant of Wilms’ tumour. The latter consists predominantly of heterogenous tissue of extraordinary diversity, which may include the presence of bone, cartilage, muscle, fat, neuroglial tissue and mature squamous epithelium. For a tumour to be termed a primary renal teratoma, Beckwith has put forth the following criteria: (i) The primary tumour should be unequivocally of renal origin, which means that the entire lesion is contained within the renal capsule and there are no teratomas in remote sites which may have metastasized to the kidney. (ii) The tumour should exhibit unequivocal heterotopic organogenesis, with clearly recognizable evidence of attempt to form organs other than kidney. Unequivocal organogenesis could be defined as the presence of immature or mature tissue arranged in a manner that is comparable to the ‘normal’ development of the organ or the mature appearance of the organ [8]. The presence of hair shafts is taken as evidence of terminal differentiation which has not been described in Wilms’ tumour [4].

Immature histologic grade, associated malignant neuroepithelial tumours and presence of metastases are associated with a poor prognosis.

In conclusion, although renal teratomas are rare and preoperative diagnosis is difficult, it must be considered in the differential diagnosis of cystic lesions and distinguished from Wilms’ tumour for the correct choice of treatment. This third case report of intrarenal teratoma occurring in renal dysplasia we also wish to draw attention to this association and highlight the possibility of misdevelopment of the urinary tract increasing the incidence of intrarenal teratomas.

References

- 1.Choi DJ, Wallace C, Fraire AE, Baiyee D. Best cases from the AFIP: intrarenal teratoma. Radiographics. 2005;25:481–485. doi: 10.1148/rg.252045153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otani M, Tsujimoto S, Miura M, Nagashima Y. Intrarenal mature cystic teratoma associated with renal dysplasia: case report and literature review. Pathol Int. 2001;51:560–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehner LP. Intrarenal teratomas occurring in infancy: report of a case with discussion of extragonadal germ cell tumors in infancy. J Pediatr Surg. 1973;8:369–378. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(73)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Govender D, Nteene LM, Chetty R, Hadley GP. Mature renal teratoma and a synchronous malignant neuroepithelial tumor of the ipsilateral adrenal gland. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:253–254. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaronson IA, Sinclair-Smith C. Multiple cystic teratomas of the kidney. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1980;104:614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzales-Crussi F. Teratoma of the kidney. In: Hartmann WH, Cowan WR, editors. Extragonadal teratomas. Atlas of tumor pathology. Second series Fascicle 18. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1984. pp. 191–192. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasad SB. Intrarenal teratoma. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59:111–112. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.59.688.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beckwith JB. Wilms’ tumor and other renal tumors of childhood: a selective review from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Pathology Center. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:481–492. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(83)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]